Abstract

Background

Metachronous gastric cancer (MGC) may develop in patients undergoing curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. As gastritis and intestinal metaplasia are notable precursors to gastric cancer, we assessed MGC risk using the Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) and Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia assessment (OLGIM) systems.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study classified the OLGA and OLGIM stages for 916 patients who had undergone endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer between 2005 and 2015. MGC development was followed up until 2020 and risk factors were evaluated using the Cox proportional hazards regression analysis.

Results

During a median follow-up of 94 months, MGC developed in 120 subjects. OLGA stages II ~ IV were significantly associated with increased MGC risk (hazard ratio [HR] 1.83, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05–3.19; HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.22–4.38; HR 2.36, 95% CI 1.16–4.78) in multivariable analysis, even after adjusting for the well-known positive predictor of Helicobacter pylori eradication. OLGIM stages II ~ IV also showed significant association (HR 2.86, 95% CI 1.29–6.54; HR 2.94, 95% CI 1.34–6.95; HR 3.64, 95% CI 1.60–8.29). 5-year cumulative incidence increased with each stage. Helicobacter pylori-eradicated patients with OLGIM stages 0 ~ II had significantly less MGC than non-eradicated patients (4.5% vs 11.8%, p = 0.022), which was not observed with OLGIM stages III ~ IV.

Conclusions

High OLGA and OLGIM stages are independent risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer, with the OLGIM staging system being a better predictor. Patients with OLGIM stages 0 ~ II are a subgroup that may benefit more from Helicobacter pylori eradication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is regarded as a curative method for treating early gastric cancer (EGC). However, ESD preserves the stomach, thereby leaving the risk for development of metachronous gastric cancer (MGC). Identifying the risk factors of MGC is important for proper risk stratification and developing guidelines with appropriate surveillance strategies.

Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia (IM) are well-known precancerous conditions for gastric cancer (GC). The updated Sydney system [1] is a method for classifying gastritis and is widely used to grade atrophy and IM. Atrophy scores combined with topographic mapping (antrum or corpus) yield useful clinical data. For example, the Operative Link on Gastritis Assessment (OLGA) staging system [2] incorporates this information to estimate GC risk. More recently, the Operative Link on Gastric Intestinal Metaplasia assessment (OLGIM) staging system [3] has been proposed to have better inter-observer agreement. Multiple studies have shown that OLGA/OLGIM staging is a good modality for assessing risk of GC development [4,5,6,7].

As in primary GC, atrophic gastritis and IM have also been suggested as risk factors for MGC [8,9,10]. However, there has been a lack of stratification of MGC risk according to the extent of gastritis. The association between OLGA/OLGIM staging and MGC has not yet been thoroughly examined. In one study [11], OLGA/OLGIM stages were investigated only in groups (0/I/II or III/IV) and reported to have no association with MGC risk. However, this study was conducted in a western country with low prevalence of gastric cancer. In another study [12], individual stages were investigated and negative results were obtained, but this study had a small sample size and short follow-up. More studies are required to validate individual OLGA/OLGIM stages and support their clinical adoption in risk stratification of MGC development.

Here we aim to investigate whether OLGA and OLGIM stages are independent risk factors for MGC in ESD-treated EGC patients.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Seoul National University Hospital (Seoul, Korea). Patients who had received ESD between January 2005 and November 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. During this period, 2,961 patients had undergone ESD for early gastric neoplasms, of which 877 received a final diagnosis of adenoma and were subsequently excluded. Among the 2,084 early gastric cancer patients, we excluded 819 for insufficient histological data for OLGA/OLGIM staging. The remaining 1,265 patients who had both valid OLGA and OLGIM staging were followed up until December 2020.

Metachronous gastric cancer was defined as newly developed gastric cancer occurring at a previously uninvolved site 1 or more years after index ESD. Neoplasms detected within 1 year after index ESD were regarded as missed synchronous lesions. We excluded synchronous neoplasms (n = 5) and metachronous adenomas (n = 64). In those who did not develop any type of neoplasm, we set a minimum cutoff period at 60 months for follow-up, on the basis of the fact that generally cancer can be considered cured if one remains in no evidence of disease (NED) status for at least 5 years. Eventually 120 metachronous gastric cancer patients and 796 control subjects were analyzed (Fig. 1).

Study population flowchart. Among the 2,961 patients who had undergone ESD between January 2005 and November 2015, we excluded 877 for adenoma diagnosis and 819 for insufficient histological data. The remaining patients were followed up for metachronous gastric cancer development. A total of 120 metachronous carcinoma patients and 796 control subjects were analyzed

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital, Korea (2205-093-1324).

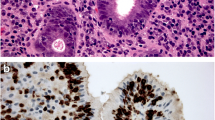

Histology

Initial ESD specimens were used to confirm an EGC diagnosis and evaluate its pathology. Tumor differentiation was determined based on the World Health Organization criteria [13], and histological type was determined based on Lauren’s classification [14].

Additional biopsy specimens for the evaluation of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia were taken from the antrum and corpus of the lesser curvature, sites recommended by the updated Sydney system. Two specimens were taken from each site. As in previous studies [4, 15], only the lesser curvature was included in the evaluation, because it has been suggested that averaging scores from lesser and greater curvatures may underestimate corpus atrophy [16, 17]. Biopsy samples were not taken from the incisura angularis based on several studies suggesting that angular biopsy provides little additional information compared to biopsies from the antrum and corpus [18,19,20] and European guidelines which also excluded angular biopsy for staging [21].

Helicobacter pylori density, polymorphonuclear cell activity, chronic inflammation, glandular atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia were graded as absent, mild, moderate, or marked (0–3, respectively), according to the updated Sydney system [1].

Based on the histological database, we classified gastritis patterns using the OLGA and OLGIM systems. The OLGA staging system [2] integrates atrophy scores and the atrophy topography (antrum and corpus), whereas the OLGIM staging system [3] uses intestinal metaplasia in place of the atrophy score.

We assessed the development of metachronous neoplasms using biopsy specimens, which had been obtained upon suspicion of pathological lesions in follow-up endoscopic evaluations.

Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) status was considered to be positive if either the rapid urease test or histology test was positive at the time of ESD. H. pylori treatment was performed after the ESD. Patients who had received H. pylori treatment were identified by administration of triple therapy (amoxicillin, clarithromycin and a proton pump inhibitor) and/or quadruple therapy (bismuth, metronidazole, tetracycline and a proton pump inhibitor). Successful eradication of H. pylori was defined by negative conversion upon follow-up urea breath test, rapid urease test, or histology test. The result of treatment was assessed after at least 4 weeks, and most cases were assessed at 3 months. If multiple test modalities had been performed and a discrepancy between results existed, a conservative stance was taken (eradication was considered successful only if all tests were negative).

Statistical analysis

For the baseline and histopathologic characteristics, continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the Student’s t test. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage) and compared using the Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. We used the Cox proportional hazards ratio regression analysis to explore the risk factors for development of metachronous gastric cancer. Age, sex, and H. pylori eradication were taken into account in comparing MGC patients and control subjects. Cumulative incidence of metachronous gastric cancer was calculated and log-rank test was performed. Subgroup analysis was performed based on H. pylori eradication. A p < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with R version 4.2.1.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the study subjects. During a median of 94.0 months of follow-up (interquartile range, 77.0–118.3 months), MGC developed in 120 out of 916 subjects. The MGC group had a greater proportion of males, but there was no significant difference in age or H. pylori positivity. On the other hand, the number of patients who received H. pylori treatment and were successfully eradicated was significantly lower in the MGC group. Initial EGC characteristics as obtained by ESD specimens (location, gross type, histologic type, and Lauren classification) did not differ between the two groups.

MGC characteristics

The developed MGCs had an average size of 2.0 ± 1.3 cm and were mostly EGCs found in the antrum. The majority had well or moderate differentiation (78.3%) and intestinal type of Lauren classification (77.5%), and invaded up to the muscularis mucosa (70.0%).

Gastritis staging using the OLGA and OLGIM systems

The OLGA and OLGIM stages were higher in the MGC group as compared to the control group (Table 2). In the MGC group, there were more OLGA stage III ~ IV subjects (28.4% vs 17.4%) and fewer OLGA stage 0 subjects (15.0% vs 26.3%).

A similar trend was found for OLGIM staging. OLGIM stages III ~ IV were more common in the MGC group (51.7% vs 35.3%), and OLGIM stage 0 was more common in the control group (15.2% vs 5.8%).

Pearson’s chi-squared values for OLGIM staging (22.662, df = 4, p < 0.001) were higher than those for OLGA staging (13.172, df = 4, p = 0.01), suggesting better discriminating ability in the OLGIM system. P for trend was significant for both OLGA and OLGIM staging systems (p < 0.001 for both).

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for the risk of MGC

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis (Table 2) showed that male sex was associated with increased risk of MGC (hazard ratio [HR] 1.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03–2.80), whereas H. pylori eradication was associated with decreased risk of MGC (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.26–0.78).

OLGA stages II ~ IV were significantly associated with higher risk of MGC (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.05–3.19, p = 0.03; HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.22–4.38, p = 0.01; HR 2.36, 95% CI 1.16–4.78, p = 0.02, respectively], even after adjusting for the above mentioned factors in multivariable analysis, including the well-known protective factor of H. pylori eradication.

OLGIM stages II ~ IV also showed significant association with greater MGC risk, which remained robust in multivariable analysis (HR 2.86, 95% CI 1.29–6.54, p = 0.01; HR 2.94, 95% CI 1.34–6.95, p = 0.01; HR 3.64, 95% CI 1.60–8.29, p = 0.002, respectively).

This association was more significant in the OLGIM stages than in the OLGA stages, as demonstrated by greater magnitudes of hazard ratios and smaller p values. Figure 2 shows the adjusted hazard ratios and confidence intervals. The adjusted hazard ratios increased in a stepwise pattern for both the OLGA and OLGIM systems.

Cumulative incidence of MGC according to OLGA/OLGIM stages

Figure 3 shows the cumulative incidence of MGC together with number at risk at 1-year intervals according to OLGA and OLGIM stages. In the OLGA system, 5-year cumulative incidence increased with stage (3.5%, 4.5%, 6.9%, 9.5%, and 9.0%, respectively). The same was true for the OLGIM system but with a more distinct separation between stages 0 ~ I and stages II ~ IV (5-year cumulative incidence = 2.3%, 2.0%, 7.3%, 7.7%, and 9.5%, respectively). P value using log-rank test was greater for OLGIM staging than OLGA staging (p < 0.001 vs p = 0.02).

Effect of H. pylori eradication on MGC development according to low/high OLGIM staging groups

Effect of H. pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer development was evaluated according to low- or high-risk OLGIM staging groups (Table 3). Conventionally, OLGIM stages 0 ~ II are classified as low risk, and stages III ~ IV as high risk.

Only 4.5% of H. pylori-eradicated patients developed MGC in OLGIM stages 0 ~ II in comparison with 11.8% of non-eradicated patients (p = 0.02), as assessed according to conventional grouping. On the other hand, MGC did not differ significantly in the H. pylori eradication group at OLGIM stages III ~ IV (12.7% vs 19.5%, p = 0.25). Similar results were obtained with OLGA stages (Supplementary Table 1).

When low-risk patients were categorized as OLGIM stages 0 ~ I only, none of them developed MGC after H. pylori eradication compared to no eradication (0.0% vs 8.6%, p = 0.006). Higher OLGIM stages (II ~ IV) showed no significant differences in development of MGC regardless of H. pylori eradication (11.2% vs 18.2%, p = 0.07). Cumulative incidence according to OLGIM stages in H. pylori-eradicated patients is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Also, we evaluated patients according to H. pylori and atrophy status as suggested by previous studies [22, 23]. Watabe et al. reported four groups of people in the general population (A: atrophy – H. pylori − , B: atrophy − H. pylori + , C: atrophy + H. pylori + , D: atrophy + H. pylori −), of which group D has the highest risk of gastric cancer. This can be explained by the fact that H. pylori burden decreases in severe atrophy. Consistent with such results, we found that patients with atrophy (OLGA ≥ 1 or OLGIM ≥ 1) but negative H. pylori had high MGC incidence, similar to those with persistent H. pylori infection (Supplementary Table 2).

Discussion

This long-term follow-up study demonstrated that the risk of MGC increases in a stepwise pattern with OLGA/OLGIM staging, and that stages II ~ IV are significantly associated with higher MGC risk. Furthermore, H. pylori eradication may be more effective in patients with low OLGA/OLGIM staging scores than in those with high scores in preventing metachronous cancer development after gastric ESD for EGC.

Gastritis staging is important and the recently updated Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report [24] has recommended OLGA/OLGIM staging as a consistent method for assessing gastric cancer risk. However, it has been unclear whether OLGA/OLGIM scores can also predict metachronous gastric cancer risk. Negative results have been reported in previous studies, but one [11] was conducted in a western country with a relatively low incidence of gastric cancer, and another [12] only had a small sample size of 20 metachronous neoplasms (13 adenomas and 7 carcinomas) which may have been insufficient for meaningful outcomes. Our study was conducted in a country with a high incidence of gastric cancer and included 120 metachronous carcinoma patients. In addition, only patients with a minimum of 60 months of follow-up were enrolled in the control group, ensuring that enough follow-up time had been warranted for the control group. Cumulative incidence increased with stage for both the OLGA and OLGIM systems. This large scale and long-term study shows that there is significant association between high OLGA/OLGIM stages and MGC development. Thus, OLGA and OLGIM staging systems were validated, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, in MGC patients. Our present study suggests that gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia are not only precancerous lesions for initial gastric cancer development but also for metachronous gastric cancer development after curative ESD for EGC.

Of the two staging systems, the OLGIM system seems to be a better predictor than the OLGA system. In previous studies of primary gastric cancer risk, higher hazard or odds ratios were found for intestinal metaplasia than atrophy [25, 26], and odds ratios for OLGIM staging increased more steeply than for OLGA staging [4]. A similar result was found for MGC patients. OLGIM stages had greater magnitudes of hazard ratios and smaller p values, suggesting that OLGIM staging has better discriminating ability than OLGA for MGC development. In addition, a clearer distinction between stages was observed for the OLGIM system in the cumulative incidence curve.

Based on previous studies [8, 27,28,29,30,31], age, sex and H. pylori eradication were taken into account in comparing MGC patients and control subjects. Consistent with those reports, male sex was associated with increased risk of MGC, whereas H. pylori eradication was associated with decreased risk of MGC. The importance of H. pylori eradication cannot be overstated. The 2015 Kyoto consensus report on gastritis [32] designated H. pylori gastritis as an infectious disease, which is now included in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. This led to a paradigm shift that all infected patients should receive treatment. In particular, the 2022 Maastricht consensus states that eradication of H. pylori is mandatory to reduce the risk of metachronous gastric cancer after curative endoscopic resection or gastric subtotal resection of early gastric cancer, with 100% agreement and grade A1 recommendation. The results of our study add evidence to this position.

In this study, 52.5% and 59.4% of the participants in the MGC and control group were positive with H. pylori. Among those, less than half received H. pylori treatment, because at the time of this study (2005 ~ 2015), H. pylori treatment was not strongly indicated in South Korea due to lack of supporting data at that time. For now, H. pylori treatment has become routine practice for ESD-treated EGC patients after the publication in 2018 [28], which provided evidence for MGC reduction in H. pylori-eradicated patients. For ethical reasons, we performed treatment for patients in this study who remained in follow-up and who had not received first/second-line treatments earlier.

The effect of H. pylori eradication on MGC development was evaluated based on low and high staging groups of the OLGIM system. Patients with low stages (0 ~ II) saw a definite effect of H. pylori eradication, because MGC development was significantly reduced (4.5% vs 11.8%, p = 0.02). When OLGIM stages 0 ~ I were evaluated as a single group, the effect was even more dramatic, with none developing MGC (0.0% vs 8.6%, p = 0.006). On the other hand, patients with higher OLGIM stages showed no significant difference in MGC recurrence regardless of H. pylori eradication. This suggests that patients with low-risk OLGIM stages may benefit more from H. pylori eradication, and those patients with stage 0 ~ II OLGIM scores must definitely be treated with an antibiotic regimen. Because metachronous cancer can develop irrespective of H. pylori eradication, endoscopic surveillance should be emphasized especially in patients with high OLGIM scores after gastric ESD for EGC. Subsequent surveillance intervals for such patients need to be optimized in the future. Randomized trials comparing annual and biannual endoscopy may be an answer to this interesting topic.

The strength of our study is that MGC patients were evaluated in a country with high gastric cancer incidence and that a long-term follow-up was conducted with a minimum cutoff of 60 months for the control group. A “true control” for metachronous gastric cancer would be one who has no recurrence during an indefinitely long period. To define a group of patients that would be close to a “true control”, we set a cutoff of 60 months on the basis of the fact that generally cancer can be considered in complete remission if it does not recur in 5 years. This ensured that our data for the control group was robust. However, this study also has several limitations. First, a single-center study cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias. Second, proper assessment of atrophy may be hampered by severe inflammatory infiltrates, inevitably leading to “not evaluable” assessment and thereby exclusion from analysis. Third, this study was conducted in a region with high incidence of gastric cancer and thus the results may not be generalized to a region with different gastric cancer rates. Another limitation is that other causes of atrophic gastritis such as autoimmune gastritis were not considered in this study. However, autoimmune gastritis is very rare in Korea [33].

In conclusion, high OLGA and OLGIM stages are independent risk factors for MGC, and OLGIM stages are better predictors than OLGA. These risk factors proved significant even after adjusting for H. pylori eradication. Patients with OLGIM stages 0 ~ II were identified as a subgroup that may benefit more from H. pylori eradication. Thus, H. pylori treatment should be performed in all ESD-treated EGC patients but especially in those with low OLGIM stages. The importance of endoscopic surveillance should be addressed for those with high OLGIM stages after gastric ESD for EGC.

References

Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated sydney system. International workshop on the histopathology of gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20(10):1161–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001.

Rugge M, Meggio A, Pennelli G, Piscioli F, Giacomelli L, De Pretis G, et al. Gastritis staging in clinical practice: the OLGA staging system. Gut. 2007;56(5):631–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.106666.

Capelle LG, de Vries AC, Haringsma J, Ter Borg F, de Vries RA, Bruno MJ, et al. The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(7):1150–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.029.

Cho SJ, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Nam BH, Kim CG, Lee JY, et al. Staging of intestinal- and diffuse-type gastric cancers with the OLGA and OLGIM staging systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(10):1292–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12515.

Yue H, Shan L, Bin L. The significance of OLGA and OLGIM staging systems in the risk assessment of gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21(4):579–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0812-3.

Yun CY, Kim N, Lee J, Lee JY, Hwang YJ, Lee HS, et al. Usefulness of OLGA and OLGIM system not only for intestinal type but also for diffuse type of gastric cancer, and no interaction among the gastric cancer risk factors. Helicobacter. 2018;23(6):e12542. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12542.

Lee JWJ, Zhu F, Srivastava S, Tsao SK, Khor C, Ho KY, et al. Severity of gastric intestinal metaplasia predicts the risk of gastric cancer: a prospective multicentre cohort study (GCEP). Gut. 2022;71(5):854–63. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324057.

Moon HS, Yun GY, Kim JS, Eun HS, Kang SH, Sung JK, et al. Risk factors for metachronous gastric carcinoma development after endoscopic resection of gastric dysplasia: retrospective, single-center study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(24):4407–15. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i24.4407.PubMedPMID:28706423;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMC5487504.

Yoon H, Kim N, Shin CM, Lee HS, Kim BK, Kang GH, et al. Risk factors for metachronous gastric neoplasms in patients who underwent endoscopic resection of a gastric neoplasm. Gut Liver. 2016;10(2):228–36. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl14472.PubMedPMID:26087797;PubMedCentralPMCID:PMC4780452.

Hahn KY, Park JC, Kim EH, Shin S, Park CH, Chung H, et al. Incidence and impact of scheduled endoscopic surveillance on recurrence after curative endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84(4):628–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1404.

Brito-Gonçalves G, Libânio D, Marcos P, Pita I, Castro R, Sá I, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with gastric superficial neoplasia and risk factors for multiple lesions after endoscopic submucosal dissection in a Western Country. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2020;27(2):76–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501939.

Shin CM, Kim N, Yoon H, Choi YJ, Park JH, Park YS, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation maker for predicting metachronous recurrence after endoscopic resection of gastric neoplasms. Cancer Res Treat. 2022. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2021.997.

Hamilton SRAL. World health organization classification of tumors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000.

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31.

Nam JH, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Nam SY, et al. OLGA and OLGIM stage distribution according to age and Helicobacter pylori status in the Korean population. Helicobacter. 2014;19(2):81–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/hel.12112.

Kim CG, Choi IJ, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Nam BH, Kook MC, et al. Biopsy site for detecting Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(3):469–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05679.x.

Lee JH, Park YS, Choi KS, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, et al. Optimal biopsy site for Helicobacter pylori detection during endoscopic mucosectomy in patients with extensive gastric atrophy. Helicobacter. 2012;17(6):405–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00972.x.

Satoh K, Kimura K, Taniguchi Y, Kihira K, Takimoto T, Saifuku K, et al. Biopsy sites suitable for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection and the assessment of the extent of atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(4):569–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.166_b.x.

Marcos-Pinto R, Carneiro F, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Wen X, Lopes C, Figueiredo C, et al. First-degree relatives of patients with early-onset gastric carcinoma show even at young ages a high prevalence of advanced OLGA/OLGIM stages and dysplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(12):1451–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05111.x.

Eriksson NK, Färkkilä MA, Voutilainen ME, Arkkila PE. The clinical value of taking routine biopsies from the incisura angularis during gastroscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37(6):532–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2005-861311.

Dinis-Ribeiro M, Areia M, de Vries AC, Marcos-Pinto R, Monteiro-Soares M, O’Connor A, et al. Management of precancerous conditions and lesions in the stomach (MAPS): guideline from the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), European Society of Pathology (ESP), and the Sociedade Portuguesa de Endoscopia Digestiva (SPED). Virchows Arch. 2012;460(1):19–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1177-8.

Watabe H, Mitsushima T, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, Wada R, Kokubo T, et al. Predicting the development of gastric cancer from combining Helicobacter pylori antibodies and serum pepsinogen status: a prospective endoscopic cohort study. Gut. 2005;54(6):764–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.055400.

Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, et al. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut. 2001;49(3):335–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.49.3.335.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327745.

You WC, Li JY, Blot WJ, Chang YS, Jin ML, Gail MH, et al. Evolution of precancerous lesions in a rural Chinese population at high risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83(5):615–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991126)83:5%3c615::aid-ijc8%3e3.0.co;2-l.

Shimoyama T, Fukuda S, Tanaka M, Nakaji S, Munakata A. Evaluation of the applicability of the gastric carcinoma risk index for intestinal type cancer in Japanese patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Virchows Arch. 2000;436(6):585–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004289900179.

Choi Y, Kim N, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, et al. The incidence and risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after gastric cancer surgery. Gut Liver. 2022;16(3):366–74. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl210202.

Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, et al. Helicobacter pylori therapy for the prevention of metachronous gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(12):1085–95. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708423.

Han SJ, Kim SG, Lim JH, Choi JM, Oh S, Park JY, et al. Long-term effects of helicobacter pylori eradication on metachronous gastric cancer development. Gut Liver. 2018;12(2):133–41. https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl17073.

Abe S, Oda I, Minagawa T, Sekiguchi M, Nonaka S, Suzuki H, et al. Metachronous gastric cancer following curative endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Clin Endosc. 2018;51(3):253–9. https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2017.104.

Nozaki I, Nasu J, Kubo Y, Tanada M, Nishimura R, Kurita A. Risk factors for metachronous gastric cancer in the remnant stomach after early cancer surgery. World J Surg. 2010;34(7):1548–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0518-0.

Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut. 2015;64(9):1353–67. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252.

Song IC, Lee HJ, Kim HJ, Bae SB, Lee KT, Yang YJ, et al. A multicenter retrospective analysis of the clinical features of pernicious anemia in a Korean population. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(2):200–4. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2013.28.2.200.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (#NRF-2022R1A2B5B01001430), the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2021), and the SNUH research fund (#03-2022-0140).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SC and YN designed the study. YN performed data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. SK and SC revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. SC supervised the project and obtained funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Seoul National University Hospital (No. 2208-072-1350). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Patient consent was waived, given the retrospective nature of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Na, Y.S., Kim, S.G. & Cho, SJ. Risk assessment of metachronous gastric cancer development using OLGA and OLGIM systems after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Gastric Cancer 26, 298–306 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-022-01361-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-022-01361-2