Abstract

Among myositis-specific antibodies, anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (anti-MDA5) is one of the antibodies with a unique spectrum that is expressed principally in clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) and, to a lesser extent, in dermatomyositis (DM). In addition to muscle and classical skin involvement, patients with anti-MDA5 DM/CADM are characterized by the expression of rapidly progressive interstitial lung diseases, vasculopathic lesions, and non-erosive arthritis. Although cardiac involvement has been described in other inflammatory myopathies, such as myocarditis, pericarditis, and conduction disorders, in anti-MDA5 DM/CADM patients, heart disease is infrequent. We report a case of a young male presenting with constitutional symptoms, polyarthritis, skin ulcers, and mild muscle weakness who developed an episode of high ventricular rate atrial fibrillation during his hospitalization. The anti-MDA5 DM diagnosis was supported by increased muscular enzymes, positive anti-MDA5 and anti-Ro52 antibodies, and the presence of organizing pneumonia. He was treated with high-dose glucocorticoids, rituximab, and beta-blocker drugs and received pharmacological cardioversion, which improved his myopathy symptoms and stabilized his heart rhythm. Here, we describe eight similar cases of anti-MDA5 DM/CADM with cardiac involvement. The case presented and the literature reviewed reveal that although rare, physicians must be aware of cardiac disease in patients with suggestive symptoms to guarantee early assessment and treatment, thereby reducing life-treating consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs) are a group of autoimmune diseases with a broad clinical spectrum characterized mainly by muscle and other organ involvement, such as the skin, joints, heart, and lungs [1]. The anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene antibody (anti-MDA5) is a myositis-specific autoantibody (MSA) against a 140-kDa polypeptide described by Sato et al. in 8 Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM) [2]. Further description found that patients with anti-MDA5 have a unique clinical phenotype that includes CADM or classical dermatomyositis (DM), rapid progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD), arthritis, and vasculopathy lesions [3, 4]. Anti-MDA5 DM/CADM represents approximately 40% of DM cases in children [5] and 10 to 25% of adult patients with DM [6, 7]. The mortality rate in this disease depends on its clinical phenotype; therefore, patients with RP-ILD have a worse prognosis [8]. Cardiac involvement is rare and has been scarcely reported in the literature. We described a case of a young male with anti-MDA5 DM with new-onset atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods

We reviewed the literature regarding heart involvement in anti-MDA5 DM/CADM in MEDLINE, EMBASE, SCOPUS, and LILACS until August 2022. We selected English- and Spanish-language-related case reports. Key terms used in the research were “heart disease,” “cardiac disease,” “MDA5,” and “dermatomyositis.” We selected eight articles [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16] that reported cardiac manifestations in patients with anti-MDA5 DM/CADM (Table 1).

Case presentation

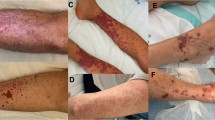

A 17-year-old male, previously asthmatic, presented to the rheumatologist with an 8-month history of polyarthritis, prolonged morning stiffness, fever, and 9-kg weight loss. Because the main clinical suspicion was rheumatoid arthritis, he was initially treated with methotrexate (15 mg QW) and prednisolone 10 mg QD without achieving a complete response. During follow-up, he described new-onset proximal muscle weakness, biphasic Raynaud’s phenomenon, and skin ulcers for 3 months, for which he was referred to the emergency department. Physical examination showed arthritis in the elbows, wrists, and several metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints with slight proximal upper limb weakness. Skin examination revealed diverse lesions: (1) hyperpigmented plaques on elbows, (2) brownish-erythematous plaques with a residual ulcer scar on joints in the hands, (3) palmar papules on the distal interphalangeal joint, and (4) violaceous macules on the tip of the hallux pulp (Fig. 1).

A, B Brownish-erythematous plaques with a residual scar of ulcers on the bilateral third metacarpophalangeal joints and arthritis on the bilateral second and third proximal interphalangeal joints (white arrows). C, D Palmar papules on the distal interphalangeal joints. E Violaceous macule on the tip of the hallux pulp

Regarding laboratory findings, the most relevant was the increase in acute phase reactants, mild normocytic anemia, and a minimal muscle enzyme elevation with a creatinine kinase level of 237 U/L (upper limit of normal [ULN] 171 U/L) lactic dehydrogenase 500 mg/dL (ULN 460 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase 59 mg/dL (ULN 45 mg/dL), and alanine aminotransferase 40 mg/dL (ULN 40 mg/dL). Skin biopsy revealed thrombotic vasculopathy and interphase dermatitis changes (Fig. 2). After ruling out other differential diagnoses, such as malignancy and infection, an MSA and myositis-associated autoantibody panel was performed. Antinuclear antibodies were positive with a cytoplasmic pattern, and anti-Ro52 and anti-MDA5 antibodies were present in low and high titers, respectively. Finally, the complete clinical picture allowed the diagnosis of anti-MDA5 DM.

Although the patient had no clinical findings suggestive of respiratory distress, high-resolution computed tomography, performed as part of the screening imaging, revealed subclinical interstitial lung involvement in organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (Fig. 3). Due to the predominance of articular symptoms, the patient was classified as Cluster 3 of the clinical phenotypes described by Allenbach [8]. Initial treatment consisted of methylprednisolone pulses (500 mg QD for three days) followed by prednisolone 1 mg/k/d and methotrexate 15 mg QW.

One day after glucocorticoid pulse therapy, the patient presented oppressive chest pain at rest, with tachycardia (152 beats per minute) and normal arterial blood pressure. An electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed during the episode showing an atrial fibrillation (AF) pattern. Therefore, he received intravenous metoprolol and pharmacologic cardioversion with amiodarone, which stabilized the heart rate and resolved the thoracic pain. Concerning cardiac assessment, troponin I and echocardiogram were normal, with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction of 54%. Additionally, cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) did not show late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) or structural alteration. Finally, 1 g of rituximab was prescribed on days 0 and 15 due to persistent and severe arthritis. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient reported a complete response of articular, muscular, and skin manifestations and a lack of cardiorespiratory symptoms or new high ventricular rate atrial fibrillation episodes.

Discussion

Anti-MDA5 DM/CADM diagnosis presents challenges since vascular and joint manifestations can occur in other IIMs, such as antisynthetase syndrome and overlapping myositis. Physical examination is crucial for establishing differences between them; a clue in the assessment is the typical expression of vascular disease in the skin. In addition to Raynaud’s phenomenon (67%) and mechanic’s hands (29%) [12], patients have a unique cutaneous phenotype, with skin lesions such as ulcers (80%) and palmar papules (60%) [17]. Additionally, arthralgia and arthritis are characteristics of the disease and are present in 70% of patients [8]. ILD is seen in almost all cases, with the rapid progressive phenotype as the most regular expression (70%) [18] and OP as the characteristic tomographic pattern [19].

Considering that approximately two thirds of patients have CADM [8] and an increased risk of RP-ILD (OR 20.4, 95% CI 9.02–46.20) [20], thoracic imaging screening is mandatory to rule out pulmonary involvement. Regarding autoantibodies, severe cutaneous and lung involvement are associated with anti-Ro antibody positivity [21], and the increase in anti-MDA5 antibody levels has been considered as a predictor of RP-ILD flares [22]. The broad clinical spectrum allowed the identification by Allenbach et al. of three clusters (pulmonary, vasculopathic, and articular), with implications for prognosis [8]. Treatment strategies depend on clinical phenotype; those with RP-ILD benefit most from immunosuppressor combinations, such as glucocorticoids and calcineurin inhibitors, with or without cyclophosphamide [23]. For refractory disease, rituximab is an option that improves pulmonary symptoms, function tests, and imaging findings [24].

The heart in immune inflammatory myopathies

Cardiac involvement in IIMs was first described in 1899 and was considered a rare presentation until the 1970s. However, more recent cohorts have shown an increase in its incidence [25, 26]. Heart disease has been reported in 9 to 75% of patients, with a wide prevalence margin due to patient selection, diagnostic tools, and the inclusion of subclinical involvement [26,27,28]. It is well recognized as a life-threatening manifestation [26, 29] and is considered by some authors to be the leading cause of death in IIMs [29, 30]. Although it is difficult to establish an accurate rate, mortality for this cause was reported in 10 to 20% of polymyositis (PM) patients [31].

The Euromyositis registry of 3067 cases of IIMs reported cardiac involvement in up to 9%, defined as pericarditis, myocarditis, arrhythmia, or sinus tachycardia due to the IIM disease process [32]. According to published literature, heart failure is the most common presentation observed in up to 45% of cases. Furthermore, a cohort study with a total of 1145 patients found an increased risk of coronary heart disease with hazard ratios of 2.21 (95% CI 1.64–2.99) in DM and 3.73 (95% CI 2.83, 4.90) in PM [33]. Unlike the described conditions, pericarditis and myocarditis are not frequent findings in IIMs; a prospective study of 26 patients found only three patients with pericarditis (12%), all with minimal and hemodynamically insignificant effusion [34]. A recent case–control study compared 31 cases of myocarditis with 31 IIM patients without cardiac involvement, finding that heart failure, arrhythmias, elevated troponin, and NT-proBNP could be relevant in the diagnosis [35]. Myocarditis in antisynthetase syndrome is described in 3.4% of cases and has no links to autoantibody specificity [36]. In the last two studies, there was a correlation between myocarditis and the presence of anti-mitochondrial M2 (AMA-M2) antibodies [35, 36].

Finally, arrhythmias such as AF also occurred, with a prevalence described in a Korean population with IIMs of 3.5%, which is higher than that in other autoimmune diseases (HR 3.29, 95% CI 1.94–5.58) [37]. Subclinical involvement is characterized by ECG abnormalities such as nonspecific changes in the ST-segment, left ventricular enlargement, and rhythm/conduction disorders [27, 38]. Two studies demonstrated an increased prevalence of ECG alterations; one reported these changes in 18% of IIM patients compared to 10% in healthy controls. In the second study, 50% of PM/DM patients had alterations versus 24% of controls (p = 0.008) [38].

The diagnostic approach to heart involvement requires biochemical tests, ECG, and imaging studies. From a systematic review, it can be concluded that a correlation exists between troponin levels in asymptomatic patients and the activity grade of IIMs and that the specificity of troponin I is better than that of troponin T levels [39, 40]. Concerning imaging tools, ventricular systolic function by echocardiography is usually normal; nonetheless, diastolic dysfunction is recurrently detected in IIMs [40, 41]. To date, novel CMR techniques are considered the most accurate myocarditis markers [42], where findings such as LGE areas (indicating scars or focal necrosis), abnormal T1, T2, and extracellular volume mapping are key and could be present despite a preserved ejection fraction [40]. Elevated cardiac biomarkers and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction are almost always present in overt myocarditis associated with IIMs [35, 40].

Chen et al. proposed an algorithm to assess heart disease in IIMs [43]. The first step is to perform troponin I level measurements, an ECG, and an echocardiogram; cardiac involvement is unlikely if these studies are normal [43]. However, if the troponin concentration is above the ULN and is not explained by other etiologies, CRM should be considered, and even myocardial biopsy in some cases [43]. Regarding immunosuppression, corticosteroid treatment outcomes in heart failure are controversial, and evidence is still insufficient [44, 45]. Severe cardiac complications should be treated according to current treatment standards.

The heart in anti-MDA5 DM/CADM

Cardiac involvement in anti-MDA5 DM/CADM is infrequent, with only eight reported cases in the literature. As in IIMs, the clinical presentation is broad, ranging from myocarditis and pericarditis to cardiac conduction disorders (Table 1). Although heart disease is usually subclinical, patients can rapidly evolve, leading to life-threatening consequences [11]. The cases have a worldwide distribution without sex predominance and are slightly more frequent in Asia. The age of presentation varies between 9 and 68 years old, with a report of three patients of pediatric age. Most of the cases had symptoms of heart failure and other palpitations, and three of them did not have a description of the symptoms. Four of eight patients presented bradyarrhythmias, including symptomatic complete atrioventricular blocks [10, 11, 15] and tachyarrhythmias such as sinus tachycardia and atrial tachycardia [9, 16].

Fifty percent of cases had a diagnosis of myocarditis confirmed by CMR or histopathology [14, 16]. The ventricular tissues of one of the patients showed atrophic myofibers and disarranged myofibrils [14]. In immunohistochemistry, Ma et al. described significant interstitial fibrosis and positive staining of cleaved-caspase 3 in atrophic cardiomyocytes [14]. Surprisingly, high-sensible troponin was negative in most patients, even those with myocarditis. On the other hand, NT-proBNP was the most frequently increased, and cardiac biomarkers such as CK-MB were less frequently assessed [14]. Only one reported case presented with pericarditis and myocarditis, with worse outcomes [10]. Although MSAs are almost always mutually exclusive, one patient was positive for anti-MDA5 and antibodies against the signal recognition particle; in this case, the heart disease was better explained by the second [14]. Concerning other antibodies, none of the eight patients had anti-AMA M2 antibodies.

Regarding other diagnostic tools, Matsuo et al. recently published a retrospective analysis comparing ECG and echocardiography findings in IIM patients with or without anti-MDA5 antibodies (21 versus 41 cases). In this cohort, although only three patients had clinical heart disease, subclinical cardiac abnormalities were frequently reported in more than half of the patients. The results showed that anti-MDA5 DM/CADM cases had significantly lower T wave amplitudes on DI, DII, aVF, and V3 to V6 leads, which improved after treatment. In addition, on echocardiogram, they presented low E and A waves and decreased movement speed of the mitral valve annulus at the septum as a reflection of the underlying diastolic dysfunction [46]. Regarding the pathogenesis of cardiac involvement, two hypotheses were put forth; the first highlighted the harmful heart effects of some cytokines, such as IL-8 and IL-10, affecting calcium and potassium channels and inducing myocarditis [46]. The second hypothesis is based on the function of MDA5 as a pattern-recognition receptor for viral cytosolic RNA. To the best of our knowledge, coxsackievirus can trigger an anti-MDA5 DM/CADM by forming complexes that are recognized by antigen-presenting cells, inducing T and B cell immune responses and antibody production [4]. The fact that these viruses are also a cause of myocardial inflammation suggests that cardiac and muscle involvement share pathogenic pathways.

Another possible explanation is linked to the harmful potential of autoantibodies. It is known that patients with anti-MDA5 DM/CADM are frequently positive for anti-Ro antibodies (33%), especially for its polypeptide of 52 kDa (anti-Ro52). The presence of these antibodies, beyond being a random association because of their high frequency in other autoimmune diseases, in anti-MDA5 DM/CADM patients has been related to RP-ILD and vasculopathic lesions. In research by Temmoku et al., double-seropositive subjects had significantly lower survival based on Kaplan curves (p = 0.001), highlighting the worse outcomes [47]. Although the pathogenic pathways of anti-Ro52 antibodies in IIMs have not been described in the literature, a theory could be extrapolated from congenital cardiac block [48], where cardiac electrophysiological abnormalities are secondary to calcium dysregulation mediated by the molecular mimicry between anti-Ro antibodies and L-type calcium channels [49].

Finally, concerning outcomes, one patient had cardiogenic shock requiring intensive care unit admission for vasoactive support, and another underwent a heart transplant with important clinical improvement on follow-up [14]. The patients received aggressive immunosuppressive treatment with different schemes, with improvements in symptoms in more than 60% of the cases. Death was reported in 3 patients [9, 10, 15]. There is no specific recommendation about cardiac disease treatment due to the low frequency; therefore, immunosuppression is guided by other manifestations, mainly pulmonary involvement.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of atrial fibrillation associated with anti-MDA5 DM/CADM in a young male with a structurally healthy heart and without any other risk factors for developing arrhythmia. In conclusion, we highlight the relevance of considering cardiac disease in patients with anti-MDA5 DM/CADM and consistent symptoms. Although the clinical spectrum is heterogeneous, the most common presentation is myocarditis and conduction disorders (mainly tachyarrhythmias). To date, there is no strong evidence of the immunosuppression influence of heart involvement in this type of myopathy. Early suspicion, an accurate assessment, and specific treatment decrease the risk of life-threatening consequences and disease progression [12].

References

Lundberg IE, Fujimoto M, Vencovsky J et al (2021) Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Nat Rev Dis Prim 7:86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-021-00321-x

Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M et al (2005) Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 52:1571–1576. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21023

Tokiyama K, H T, Yokota E, (1990) Two cases of amyopathic dermatomyositis with fatal rapidly progressive interstitial pneumonitis. Ryumachi 30:204–209

Mehta P, Machado PM, Gupta L (2021) Understanding and managing anti-MDA 5 dermatomyositis, including potential COVID-19 mimicry. Rheumatol Int 41:1021–1036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04819-1

Yasin SA, Schutz PW, Deakin CT et al (2019) Histological heterogeneity in a large clinical cohort of juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy: analysis by myositis autoantibody and pathological features. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 45:495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/nan.12528

Betteridge Z, Tansley S, Shaddick G et al (2019) Frequency, mutual exclusivity and clinical associations of myositis autoantibodies in a combined European cohort of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients. J Autoimmun 101:48–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2019.04.001

Sato S, Murakami A, Kuwajima A et al (2016) Clinical utility of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 autoantibodies. PLoS ONE 11:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154285

Allenbach Y, Uzunhan Y, Toquet S et al (2020) Different phenotypes in dermatomyositis associated with anti-MDA5 antibody: study of 121 cases. Neurology 95:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000009727

Sakurai N, Nagai K, Tsutsumi H, Ichimiya S (2011) Anti-CADM-140 antibody-positive Juvenile dermatomyositis with rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease and cardiac involvement. J Rheumatol 38:963–964. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.101220

Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibáñez K et al (2014) Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 28:1097–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12300

Ryan ME, Cortez D, Dietz KR et al (2021) Anti-MDA5 juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathy with second-degree heart block but no skin or lung involvement: a case report. BMC Rheumatol 5:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41927-021-00180-9

Kurtzman DJB, Vleugels RA (2018) Anti-melanoma differentiation–associated gene 5 (MDA5) dermatomyositis: a concise review with an emphasis on distinctive clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol 78:776–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.010

Wang J, Budamagunta MS, Voss JC et al (2013) Antimitochondrial antibody recognition and structural integrity of the inner lipoyl domain of the E2 subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. J Immunol 191:2126–2133. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1301092

Ma X, Xu L, Li Y, Bu B (2021) Immunotherapy reversed myopathy but not cardiomyopathy in a necrotizing autoimmune myopathy patient with positive anti-SRP and MDA-5 autoantibodies. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 21:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-021-01900-2

Sakamoto N, Ishimoto H, Nakashima S et al (2019) Clinical features of Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease without signs of dermatomyositis. Intern Med 58:837–841. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.1516-18

Gupta R, Kumar S, Gow P et al (2020) Anti-MDA5-associated dermatomyositis. Intern Med J 50:484–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/imj.14789

Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J et al (2011) The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 65:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.016

Koga T, Fujikawa K, Horai Y et al (2012) The diagnostic utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody testing for predicting the prognosis of Japanese patients with DM. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 51:1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ker518

Egashira R (2021) High-resolution ct findings of myositis-related interstitial lung disease. Medicina (Kaunas) 57:1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57070692

Chen Z, Cao M, Plana MN et al (2013) Utility of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody measurement in identifying patients with dermatomyositis and a high risk for developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease: a review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 65:1316–1324. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21985

Huang K, Vinik O, Shojania K et al (2019) Clinical spectrum and therapeutics in Canadian patients with anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)-positive dermatomyositis: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int 39:1971–1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-019-04398-2

Matsushita T, Mizumaki K, Kano M et al (2017) Antimelanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 antibody level is a novel tool for monitoring disease activity in rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease with dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol 176:395–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.14882

Romero-Bueno F, Diaz del Campo P, Trallero-Araguás E et al (2020) Recommendations for the treatment of anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5-positive dermatomyositis-associated rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:776–790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.03.007

So H, Wong VTL, Lao VWN et al (2018) Rituximab for refractory rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease related to anti-MDA5 antibody-positive amyopathic dermatomyositis. Clin Rheumatol 37:1983–1989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-018-4122-2

Hochberg MC, Feldman D, Stevens MB (1986) Adult onset polymyositis/dermatomyositis: an analysis of clinical and laboratory features and survival in 76 patients with a review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 15:168–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-0172(86)90014-4

Dankó K, Ponyi A, Constantin T et al (2004) Long-term survival of patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies according to clinical features: a longitudinal study of 162 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 83:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.md.0000109755.65914.5e

Diederichsen LP, Simonsen JA, Diederichsen AC et al (2016) Cardiac abnormalities in adult patients with polymyositis or dermatomyositis as assessed by noninvasive modalities. Arthritis Care Res 68:1012–1020. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22772

Wang H, Liu HX, Wang YL et al (2014) Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with dermatomyositis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. J Rheumatol 41:495–500. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130346

Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Moss K, Isenberg DA (2002) Outcome in patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis: morbidity and mortality. Rheumatology 41:22–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.22

Limaye V, Hakendorf P, Woodman RJ et al (2012) Mortality and its predominant causes in a large cohort of patients with biopsy-determined inflammatory myositis. Intern Med J 42:191–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02406.x

Lundberg IE (2006) The heart in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Rheumatology 45:18–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel311

Lilleker JB, Vencovsky J, Wang G et al (2018) The EuroMyositis registry: an international collaborative tool to facilitate myositis research. Ann Rheum Dis 77:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211868

Weng MY, Lai ECC, Yang YHK (2019) Increased risk of coronary heart disease among patients with idiopathic inflammatory myositis: a nationwide population study in Taiwan. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 58:1935–1941. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez076

Taylor AJ, Wortham DC, Robert Burge J, Rogan KM (1993) The heart in polymyositis: a prospective evaluation of 26 patients. Clin Cardiol 16:802–808. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.4960161110

Liu Y, Fang L, Chen W et al (2020) Identification of characteristics of overt myocarditis in adult patients with idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 10:405–420. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2020.03.04

Dieval C, Deligny C, Meyer A et al (2015) Myocarditis in patients with antisynthetase syndrome: prevalence, presentation, and outcomes. Med (United States) 94:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000000798

Baek YS, Kim TH, Uhm JS et al (2016) Prevalence and the clinical outcome of atrial fibrillation in patients with autoimmune rheumatic disease. Int J Cardiol 214:4–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.083

Deveza LMA, Miossi R, De Souza FHC et al (2016) Electrocardiographic changes in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Rev Bras Reumatol 56:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2014.08.012

Lilleker JB, Diederichsen ACP, Jacobsen S et al (2018) Using serum troponins to screen for cardiac involvement and assess disease activity in the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatol (United Kingdom) 57:1041–1046. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/key031

Fairley JL, Wicks I, Peters S, Day J (2021) Defining cardiac involvement in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a systematic review. Rheumatology 61:103–120. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab573

Lu Z, Wei Q, Ning Z et al (2013) Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction - Early cardiac impairment in patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis: a tissue doppler imaging study. J Rheumatol 40:1572–1577. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.130044

Kotanidis CP, Bazmpani MA, Haidich AB et al (2018) Diagnostic accuracy of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in acute myocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 11:1583–1590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.12.008

Chen F, Peng Y, Chen M (2018) Diagnostic approach to cardiac involvement in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: a strategy combining cardiac troponin I but not T assay with other methods. Int Heart J 59:256–262. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.17-204

Stern R, Godbold JH, Chess Q, Kagen LJ (1984) ECG abnormalities in polymyositis. Arch Intern Med 144:2185–2189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.144.11.2185

Allanore Y, Vignaux O, Arnaud L et al (2006) Effects of corticosteroids and immunosuppressors on idiopathic inflammatory myopathy related myocarditis evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Rheum Dis 65:249–252. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2005.038679

Matsuo T, Sasai T, Nakashima R et al (2022) ECG changes through immunosuppressive therapy indicate cardiac abnormality in anti-MDA5 antibody-positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Front Immunol 12:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.765140

Temmoku J, Sato S, Fujita Y et al (2019) Clinical significance of myositis-specific autoantibody profiles in Japanese patients with polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98:e15578. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015578

Ambrosi A, Dzikaite V, Park J et al (2012) Anti-Ro52 monoclonal antibodies specific for amino acid 200–239, but not other Ro52 epitopes, induce congenital heart block in a rat model. Ann Rheum Dis 71:448–454. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200414

Karnabi E, Qu Y, Wadgaonkar R et al (2010) Congenital heart block: identification of autoantibody binding site on the extracellular loop (domain I, S5–S6) of α1D L-type Ca channel. J Autoimmun 34:80–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaut.2009.06.005

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Colombia Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally to the conception and article design, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of the data, work drafting, and critical revision of the intellectual content. Additionally, the authors decided on the final version to be published and are responsible for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Quintero-González, D.C., Navarro-Beleño, K., López-Gutiérrez, L.V. et al. Cardiac involvement in anti-MDA5 dermatomyositis: a case-based review. Clin Rheumatol 42, 949–958 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06401-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06401-x