Abstract

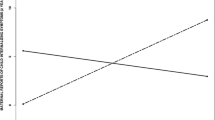

Positive maternal mental health can improve perceptions of stressful situations and promote the use of adaptive coping strategies. However, few studies have examined how positive maternal mental health affects children’s development. The aims of this study were to examine the associations between positive maternal mental health and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and to ascertain whether positive maternal mental health moderated the associations between prenatal stress and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. This study is based on the Norwegian Mother, Father, and Child Cohort Study (MoBa), and comprised 36,584 mother–child dyads. Prenatal stress was assessed using 41 self-reported items measured during pregnancy. Positive maternal mental health (self-efficacy, self-esteem, and enjoyment) was assessed by maternal report during pregnancy and postpartum. Child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were assessed by maternal report at age 5. Structural equation modeling was used for analysis. Maternal self-efficacy, self-esteem, and enjoyment were negatively associated with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in males and females. The association between prenatal stress and internalizing symptoms in males was stronger at low than at high levels of maternal self-esteem and enjoyment, whereas for females, the association was stronger at low than at high levels of maternal self-esteem and self-efficacy. This study provides evidence of associations between positive maternal mental health and children’s mental health, and suggests that higher positive maternal mental health may buffer against the impacts of prenatal stress. Positive maternal mental health may represent an important intervention target to improve maternal–child well-being and foster intergenerational resilience.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A et al (2004) Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 103(4):698–709. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f

Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN et al (2005) Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol 106:1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db

Ward TS, Kanu FA, Robb SW (2017) Prevalence of stressful life events during pregnancy and its association with postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch Womens Ment Health 20:161–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0689-2

Burns ER, Farr SL, Howards PP, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2015) Stressful life events experienced by women in the year before their infants’ births–United States, 2000–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 64:247–251

Barker DJP (1990) The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. Br Med J 301:1111. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111

Glover V, O’Connor TG, O’Donnell K (2010) Prenatal stress and the programming of the HPA axis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 35:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.11.008

Glover V (2011) Annual research review: prenatal stress and the origins of psychopathology: an evolutionary perspective. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 52:356–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02371.x

Bassi M, Delle Fave A, Cetin I et al (2017) Psychological well-being and depression from pregnancy to postpartum among primiparous and multiparous women. J Reprod Infant Psychol 35:183–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2017.1290222

Varin M, Palladino E, Orpana HM et al (2020) Prevalence of positive mental health and associated factors among postpartum women in Canada: findings from a national cross-sectional survey. Matern Child Health J 24:759–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-020-02920-8

Huppert FA, Whittington JE (2003) Evidence for the independence of positive and negative well-being: implications for quality of life assessment. Br J Health Psychol 8:107–122. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910703762879246

Joshanloo M (2016) Revisiting the empirical distinction between hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of well-being using exploratory structural equation modeling. J Happiness Stud 17:2023–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9683-z

Keyes CLM, Shmotkin D, Ryff CD (2002) Optimizing well-being: the empirical encounter of two traditions. J Pers Soc Psychol 82:1007–1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.1007

Delle Fave A, Massimini F, Bassi M (2011) Hedonism and eudaimonism in positive psychology. In: Delle Fave A, Massimini F, Bassi M (eds) Psychological selection and optimal experience across cultures. Cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology, vol 2. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 3–18

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2001) On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol 52:141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Srivastava K (2011) Positive mental health and its relationship with resilience. Ind Psychiatry J 20:75–76. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.102469

Carver CS, Gaines JG (1987) Optimism, pessimism, and postpartum depression. Cognit Ther Res 11:449–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01175355

Lobel M, Yali AM, Zhu W et al (2002) Beneficial associations between optimistic disposition and emotional distress in high-risk pregnancy. Psychol Heal 17:77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440290001548

Rini CK, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA (1999) Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Heal Psychol 18:333–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.18.4.333

Lau Y, Tha PH, Wong DFK et al (2016) Different perceptions of stress, coping styles, and general well-being among pregnant Chinese women: a structural equation modeling approach. Arch Womens Ment Health 19:71–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-015-0523-2

Yali AM, Lobel M (2002) Stress-resistance resources and coping in pregnancy. Anxiety Stress Coping 15:289–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/1061580021000020743

Grote NK, Bledsoe SE (2007) Predicting postpartum depressive symptoms in new mothers: the role of optimism and stress frequency during pregnancy. Heal Soc Work 32:107–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/32.2.107

Trompetter HR, de Kleine E, Bohlmeijer ET (2017) Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cognit Ther Res 41:459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9774-0

Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC, Koestner R (2012) The determinants of negative maternal parenting behaviours: maternal, child, and paternal characteristics and their interaction. Early Child Dev Care 182:683–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.572165

Hanley GE, Brain U, Oberlander TF (2013) Infant developmental outcomes following prenatal exposure to antidepressants, and maternal depressed mood and positive affect. Early Hum Dev 89:519–524. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARLHUMDEV.2012.12.012

Bolten MI, Fink NS, Stadler C (2012) Maternal self-efficacy reduces the impact of prenatal stress on infant’s crying behavior. J Pediatr 161:104–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.044

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K et al (2016) Cohort profile update: the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 45:382–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw029

Schreuder P, Alsaker E (2014) The Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa)—MoBa recruitment and logistics. Nor Epidemiol 24:23–27. https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v24i1-2.1754

Cecil CAM, Lysenko LJ, Jaffee SR et al (2014) Environmental risk, oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) methylation and youth callous-unemotional traits: a 13-year longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.95

Rijlaarsdam J, Pappa I, Walton E et al (2016) An epigenome-wide association meta-analysis of prenatal maternal stress in neonates: a model approach for replication. Epigenetics 19:1071–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/15592294.2016.1145329

Cortes Hidalgo AP, Neumann A, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ et al (2018) Prenatal maternal stress and child IQ. Child Dev 91:347–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13177

Leganger A, Kraft P, Røysamb E (2000) Perceived self-efficacy in health behaviour research: conceptualisation, measurement and correlates. Psychol Heal 15:51–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440008400288

Tambs K, Røysamb E (2014) Selection of questions to short-form versions of original psychometric instruments in MoBa. Nor Epidemiol 24:195–201. https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v24i1-2.1822

Rosenberg M (1986) Conceiving the self. Krieger, Malabar

Izard CE, Libero DZ, Putnam P, Haynes OM (1993) Stability of emotion experiences and their relations to traits of personality. J Pers Soc Psychol 64:847–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.5.847

Blascovich J, Tomaka J (1991) Measures of self-esteem. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS (eds) Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. Academic Press, pp 115–160

Scholz U, Doña BG, Sud S, Schwarzer R (2002) Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. Eur J Psychol Assess. https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242

Achenbach TM, Ruffle TM (2000) The child behavior checklist and related forms for assessing behavioral/emotional problems and competencies. Pediatr Rev 18:242–251. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.21-8-265

Nøvik TS (1999) Validity of the child behaviour checklist in a Norwegian sample. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 8:247–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007870050098

Zachrisson HD, Dearing E, Lekhal R, Toppelberg CO (2013) Little evidence that time in child care causes externalizing problems during early childhood in Norway. Child Dev 84:1152–1170. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12040

Jacka FN, Ystrom E, Brantsaeter AL et al (2013) Maternal and early postnatal nutrition and mental health of offspring by age 5 years: a prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:1038–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.07.002

Sutherland S, Brunwasser SM (2018) Sex differences in vulnerability to prenatal stress: a review of the recent literature. Curr Psychiatry Rep 20:1–2

Enders CK, Bandalos DL (2001) The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Struct Equ Model 8:430–457. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

McDonald RP, Ho MHR (2002) Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychol Methods 7:64–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6:1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Klein A, Moosbrugger H (2000) Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika 65:457–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338

Johnson PO, Neyman J (1936) Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat Res Mem 1:57–93

Lin H (2020) Probing two-way moderation effects: a review of software to easily plot Johnson-Neyman figures. Struct Equ Model 27:494–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2020.1732826

Phua DY, Kee MKZL, Koh DXP et al (2017) Positive maternal mental health during pregnancy associated with specific forms of adaptive development in early childhood: evidence from a longitudinal study. Dev Psychopathol 29:1573–1587. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417001249

Kraybill JH, Bell MA (2013) Infancy predictors of preschool and post-kindergarten executive function. Dev Psychobiol 55:530–538. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21057

Keyes CLM, Dhingra SS, Simoes EJ (2010) Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental Illness. Am J Public Health 100:2366–2371. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245

O’Connor M, Sanson AV, Toumbourou JW et al (2017) Does positive mental health in adolescence longitudinally predict healthy transitions in young adulthood? J Happiness Stud 18:177–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9723-3

Phua DY, Kee MZL, Meaney MJ (2020) Positive maternal mental health, parenting, and child development. Biol Psychiatry 87:328–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.09.028

Sanders MR, Woolley ML (2005) The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: implications for parent training. Child Care Health Dev 31:65–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00487.x

Clayborne ZM, Kingsbury M, Sampasa-Kinyaga H et al (2020) Parenting practices in childhood and depression, anxiety, and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: a systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56:619–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01956-z

Yap MBH, Pilkington PD, Ryan SM, Jorm AF (2014) Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 156:8–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007

Yap MBH, Jorm AF (2015) Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 175:424–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050

Brody GH, Flor DL (1997) Maternal psychological functioning, family processes, and child adjustment in rural, single-parent, African American families. Dev Psychol 33:1000–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.1000

Mayhew KP, Lempers JD (1998) The relation among financial strain, parenting, parent self-esteem, and adolescent self-esteem. J Early Adolesc 18:145–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431698018002002

McDonald SW, Kingston D, Bayrampour H et al (2014) Cumulative psychosocial stress, coping resources, and preterm birth. Arch Womens Ment Health 17:559–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0436-5

Papoušek M, Von Hofacker N (1998) Persistent crying in early infancy: a non-trivial condition of risk for the developing mother-infant relationship. Child Care Health Dev 24:395–424. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00091.x

Brown M, Heine RG, Jordan B (2009) Health and well-being in school-age children following persistent crying in infancy. J Paediatr Child Health 45:254–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01487.x

Rocchino GH, Dever BV, Telesford A, Fletcher K (2017) Internalizing and externalizing in adolescence: the roles of academic self-efficacy and gender. Psychol Sch 54:905–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22045

Aunola K, Stattin H, Nurmi J-E (2000) Adolescents’ achievement strategies, school adjustment, and externalizing and internalizing problem behaviors. J Youth Adolesc 29:289–306. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005143607919

Kohlhoff J, Barnett B (2013) Parenting self-efficacy: links with maternal depression, infant behaviour and adult attachment. Early Hum Dev 89:249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EARLHUMDEV.2013.01.008

Yi CY, Gentzler AL, Ramsey MA, Root AE (2016) Linking maternal socialization of positive emotions to children’s behavioral problems: the moderating role of self-control. J Child Fam Stud 25:1550–1558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0329-x

Duckworth AL, Steen TA, Seligman MEP (2005) Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 1:629–651. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154

Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S (2009) Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 65:467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Matvienko-Sikar K, Dockray S (2017) Effects of a novel positive psychological intervention on prenatal stress and well-being: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Women and Birth 30:e111–e118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.10.003

Corno G, Etchemendy E, Espinoza M et al (2018) Effect of a web-based positive psychology intervention on prenatal well-being: a case series study. Women and Birth 31:e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.005

Sanders MR, Kirby JN, Tellegen CL, Day JJ (2014) The triple P-positive parenting program: a systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clin Psychol Rev 34:337–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.04.003

Jones TL, Prinz RJ (2005) Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: a review. Clin Psychol Rev 25:341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK et al (2009) Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 23:597–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01062.x

Hudson NW, Lucas RE, Donnellan MB (2017) Day-to-day affect is surprisingly stable: a 2-year longitudinal study of well-being. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 8:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616662129

Nast I, Bolten M, Meinlschmidt G, Hellhammer DH (2013) How to measure prenatal stress? A systematic review of psychometric instruments to assess psychosocial stress during pregnancy. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 27:313–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12051

Acknowledgements

The Norwegian Mother, Father and Child Cohort Study is supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research. We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study. The consent given by the participants does not allow for storage of data on an individual level in repositories or journals. Researchers who want access to data sets for replication should submit an application to www.helsedata.no. Access to data sets requires approval from The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway and an agreement with MoBa.

Funding

The present study was partially supported by the Research Council of Norway (RCN; project # 218373) and through RCN’s Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project # 262700, RCN’s guest research program, and the Canada Research Chairs program for Dr. Colman. Dr. Nilsen was supported by RCN (project # 296770). Dr. Torvik was supported by RCN (project #300668). Dr. Bekkhus was supported by RCN (project # 301004 and 288083). Dr. Gilman’s contribution to this research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Dr. Khandaker acknowledges funding support from the Wellcome Trust, UK (grant code: 201486/Z/16/Z), the MQ: transforming Mental Health, UK (grant code: MQDS17/40), the Medical Research Council, UK (grant code: MC_PC_17213 and grant code: MR/S037675/1), and the BMA Foundation, UK (J Moulton grant 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (#2013/2061). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clayborne, Z.M., Nilsen, W., Torvik, F.A. et al. Positive maternal mental health attenuates the associations between prenatal stress and children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32, 1781–1794 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01999-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-022-01999-4