Abstract

Purpose

To investigate variation in treatment decisions among spine surgeons in South Africa and the association between surgeon characteristics and the treatment they select.

Methods

We surveyed 79 South African spine surgeons. We presented four vignettes (cervical spine distractive flexion injury, lumbar disc herniation, degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis, and insufficiency fracture) for them to assess and select treatments. We calculated the index of qualitative variation (IQV) to determine the degree of variability within each vignette. We used Fisher’s exact, and Kruskal–Wallis tests to assess the relationships between surgeons’ characteristics and their responses per vignette. We compared their responses to the recommendations of a panel of spine specialists.

Results

IQVs showed moderate to high variability for cervical spine distractive flexion injury and insufficiency fracture and slightly lower levels of variability for lumbar disc herniation and degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis. This confirms the heterogeneity in South African spine surgeons’ management of spinal pathologies. The surgeon characteristics associated with their treatment selection that were important were caseload, experience and training, and external funding. Also, 19% of the surgeons selected a treatment option that the Panel did not support.

Conclusion

The findings make a case for evaluating patient outcomes and costs to identify value-based care. Such research would help countries that are seeking to contract with providers on value. Greater uniformity in treatment and easily accessible outcomes reporting would provide guidance for patients. Further investment in training and participation in fellowship programs may be necessary, along with greater dissemination of information from the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Treatment of spinal pathologies is heterogeneous [1,2,3,4]. The patient’s clinical condition and overall health, coupled with other demand-side characteristics like age, expectations, and insurance status, could influence the surgeon’s choice of treatment [3, 5]. Supply-side factors, such as constantly evolving technology and surgical techniques and the scarcity of globally accepted evidence-based guidelines, could also explain treatment variation [1, 6,7,8]. Surgeons’ practice setting, financial incentives and background, including their training, age and experience, may also influence their professional opinion [1, 5, 7, 8].

Choice of treatment has implications for patient outcomes and costs [7] and therefore the value of the care received [9]. As countries’ health systems move towards value-based contracting, funders need to understand surgeons’ decision-making so they can contract with them in a way that provides value to the patient [7]. This is important for countries like South Africa that are moving toward a National Health Insurance. In South Africa, as in other developing countries, private sector practitioners have discretion in how they treat patients and can potentially offer patients more technologically advanced treatment than is available in the public sector. However, as a result, treatments can vary considerably and may be unnecessary or inappropriate. The Competition Commission’s Health Market Inquiry found that the effect of supplier-induced demand on practitioner behavior is partly responsible for rising costs in private healthcare [10]. The country lacks the necessary formal monitoring and reporting of health outcomes to assess whether practitioners’ treatment decisions provide value and improve patient outcomes.

We need to know more about the variation in spine surgeons’ treatment decisions in developing countries like South Africa. We investigated this variation in a sample of 79 spine surgeons and looked for associations between surgeon characteristics and the treatments chosen. Most treatment variation studies focused on developed countries. The findings of these studies may not be directly transferable to developing countries. Our study adds to the small body of research from the Global South assessing treatment variation and supply-side factors that influence surgeon variation in the treatment of spinal pathologies.

Methods

We developed a survey and administered it at the South African Spine Society (SASS) annual conference in 2021. It was intended for orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons practicing spine surgery. We used the SASS conference to avoid the likelihood of the survey going to surgeons who do not regularly operate on the spine.

The first section of the paper-based survey asked surgeon-specific questions based on characteristics identified in the literature [6,7,8, 13]. These were: type of specialty, the university where specialist training was completed, age, length of time in practice, time spent working in the public sector, number of surgeries per month, and designated service provider (DSP) for a health insurer. ‘DSP’ refers to an agreement where the surgeon provides an insurer’s members with diagnosis, treatment, and care for pre-negotiated rates. The second section consisted of four vignettes of common pathologies that spine surgeons treat. Treatment options for the vignettes ranged from conservative treatments to complex surgical procedures. See Table 1 for details. The survey is available in Annexure A.

Our Expert Panel consisted of three spine specialists who are fellowship-trained and current or previous heads of their disciplines at tertiary hospitals. Two of them work in research universities, and two of them provide surgical services in the private sector. For each of the four vignettes, the Panel was asked to identify their preferred treatment option and two treatment options that they did not support.

The responses were captured on Survey CTO. Although the survey asked respondents to indicate their preferred treatment option, a small number of surgeons did not follow this instruction and selected more than one treatment option and/or ranked options. If a surgeon selected more than one response to a question and ranked their responses, the option ranked number 1 was recorded as their preferred option. If surgeons selected more than one response and did not rank their responses, or if the question was omitted, it was not possible to determine the respondent’s preferred option and the response was counted as missing.

To analyze the data, we first summarized surgeon characteristics. Next, we illustrated the percentage of responses for each treatment option per vignette and indicated the Panel’s preferred and unsupported treatment options. We calculated the percentage of respondents who selected an unsupported response for at least one of the four vignettes.

We calculated the index of qualitative variation (IQV) to determine the degree of variability within each of the vignettes. An IQV ranges from 0, indicating no variability, to 1, indicating maximum variability [11]. In the current study, totals above 0.8 were considered highly variable [12]. We then calculated the proportion of cases that were not the Panel’s preferred answers. We used the Fisher’s exact and Kruskal–Wallis tests to assess multiple exploratory hypotheses on whether different surgeons’ characteristics (as mentioned above) were associated with the treatment options they choose. A result of p < 0.05 was considered important. We then provide frequencies and percentages for treatments and surgeon characteristics where p < 0.05. To ensure confidentiality, we combined the responses of four of the under-represented universities and labeled the universities where specialists trained from A to E–G. Given that this was an exploratory study, no adjustments were made for the multiple comparisons. Accordingly, findings where p < 0.05 should not be considered statistically significant and need to be interpreted with caution. We then provide a summary of the various results per vignette.

Results

The conference was attended by 161 delegates. This included South African spine surgeons, who were eligible to participate in the survey, and other medical professionals (e.g. specialists-in-training, physiotherapists, and researchers). Seventy-nine spine surgeons completed the survey, a response rate of > 50%. The total number of South African spine surgeons among the delegates could not be determined, thus it was not possible to calculate a precise response rate. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 79 respondents and Table 3 summarizes the treatment option selection per vignette./

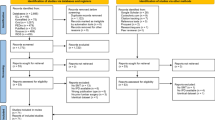

Figure 1 shows the percentage of surgeons who selected each treatment option. It also shows the options the Panel supported and did not support for each vignette as well as their preferred option (for Vignettes 2, 3 and 4). The Panel did not identify a preferred option for V1. Of the 79 surgeons, 13 selected a treatment option that the Panel did not support for one of the four vignettes, and 2 selected unsupported treatment options for two of the vignettes.

Surgeons’ selections of treatment options. Note The bars represent the percentage of surgeons that selected the treatment option. The light grey bars represent treatment options that the Panel supported, with a star indicating the Panel’s preferred option. The black bars represent the two treatment options that the Panel did not support. For Vignette 4, no surgeon selected Corpectomy, stutgraft and instrument fusion which is the second option that the Panel did not support

Table 4 shows the IQV results. All four vignettes show some degree of variability, with the most variability occurring for V1 (distractive flexion injury of the cervical spine) and V4 (insufficiency fracture). Both V1 and V4’s IQVs were just below the cutoff of 0, 8 to be considered highly variable.

We assessed various hypotheses to test the association between each of the surgeon characteristics and the treatment options they chose. Given the multiple hypothesis testing, these findings can only add exploratory descriptive evidence to the literature on this important topic. The reported significance of associations is not robust as there have not been any adjustments for family wise error rates. Table 5 shows the relevant p values for the tests of association between treatment options and surgeon characteristics. The results suggest that no one characteristic was consistently important across all four of the vignettes. University of specialist training, years in practice, time spent in the public sector, and belonging to a DSP network had p < 0.05 in at least one vignette.

Table 6 shows the frequencies and percentages for each of the characteristics where p < 0.05.

Vignette 1: distractive flexion injury of the cervical spine

Of the 79 responses, 54% selected a collar and 41% selected either an anterior (28%) or posterior (13%) fusion procedure. The Panel did not identify an ideal treatment but considered all those appropriate. Some surgeons may not have identified a subtle posterior ligamentous disruption in the image in the printed handout, which may explain the choice of the conservative collar option. Those who chose one of the two simple fusion options may have identified it. Both the collar and the fusion options would achieve an absence of pain. Reaching this outcome could take longer with the collar option, but it might be the only option available in the resource-constrained public sector. The Panel’s unsupported treatment options of skeletal traction or combined anterior and posterior fusion were chosen by 4 of the surgeons.

The Fisher’s exact p value showed an important association with the DSP characteristic (p = 0.024).

Vignette 2: lumbar disc herniation

Of the 76 responses, 66% selected a microdiscectomy, the Panel’s preferred treatment. The patient had already undergone conservative treatment with little success; however, 26% selected to continue with structured conservative treatment or epidural or similar procedure. The Panel did not support either of the decompression and fusion treatment options (chosen by 6 (8%)).

The association between the characteristics and treatment options all had p > 0.05.

Vignette 3: degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis

Of the 76 responses, 88% selected one of the three fusion options. Only 16% of the surgeons selected the simpler of the fusions and the Panel’s preferred treatment (decompression and fusion, posterior only), 70% selected the more complex decompression and fusion, including interbody fusion, posterior approach. The Panel did not support the decompression and fusion (including interbody fusion) anterior approach, although 2 of the surgeons selected this option. Of the 9 (12%) who selected conservative treatment, 4 (5%) selected structured conservative treatment, which the Panel also did not support.

In the tests of association, the university of specialist training (p = 0.022) and the number of surgeries per month (p = 0.030), were important predictors of treatment selection.

Vignette 4: insufficiency fracture

Of the 77 surgeons, 55% selected the conservative treatment of analgesia/ brace and mobilize, the Panel’s selected option. Nearly all the rest (44%) selected minimally invasive procedures of either kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty. The Panel did not support posterior instrumented fusion (chosen by one of the surgeons) or corpectomy, stutgraft, and instrument fusion (combined anterior and posterior) (chosen by none of the surgeons).

Two characteristics were associated with the treatment selected in both scenarios with p > 0.05: years in practice (p = 0.036) and time spent in the public sector (p = 0.006).

Discussion

The treatment variation IQV tests showed moderate to high variability for the cervical spine distractive flexion injury (V1) and insufficiency fracture (V4) and slightly lower levels of variability for the lumbar disc herniation (V2) and degenerative spondylolisthesis with stenosis (V3). This confirms that the heterogeneity in the management of spinal pathologies found elsewhere [1,2,3,4, 13] is also present in South Africa.

Most variation occurred between treatment options that the Panel deemed acceptable. This illustrates the lack of consensus among surgeons and shows there is more than one acceptable treatment option for a given spinal pathology [13]. A formal mechanism to measure patient outcomes would allow for better comparisons of the various treatment options available for one type of pathology.

The finding that 15/79 (19%) of surgeons selected one of the Panel’s unsupported treatment options emphasizes the significance of variation for the patient. Two patients with similar pathologies may receive very different treatments depending on their surgeon selection [8]. The selection could have financial and outcome implications, both of which are unknown to the patient before commencing treatment [6, 7]. The number of surgeons selecting an unsupported treatment option flags the urgent need for further dissemination of recent literature, skill-sharing, and training.

Our investigation of the association between surgeon characteristics and the treatment options selected was inspired by earlier studies [3, 6, 9, 11, 13]. Our vignettes are different, but we used similar variables to test the association.

The Fishers’ exact, and Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed that surgeon characteristics associations with surgeons’ treatment selection were p > 0.05 across all vignettes. There were no important differences between surgeons’ selections for any of the vignettes according to their specialty or age. This is unlike Irwin et al.’s (2005) survey of 30 orthopedic surgeons and neurosurgeons that found significant differences for these characteristics [3, 5]. Hussain et al. (2011) also found that specialty mattered, with orthopedic surgeons selecting more aggressive treatment for lumbar disc herniations [13].

The exploratory testing suggested that three surgeon characteristics were worth further investigation (this study was not designed to determine statistical significance): caseload, years in practice and training, and external funding.

Caseload

Surgeons with higher caseloads were more likely to select a more complex surgical procedure over a simpler procedure or conservative care. For the degenerative spondylolisthesis stenosis (V3) surgeons doing more than 10 surgeries per month were more likely to select the decompression and fusion posterior approach including interbody than the more conservative decompression and fusion posterior approach without interbody fusion. This appears to support Mroz et al.’s findings (2014) that surgeons with higher caseloads were likely to select more complex procedures than their less busy colleagues [6].

Years in practice and training

Disparities in surgeons’ training and experience may influence their future behavior [1, 3, 5, 8, 13]. University of specialist training was associated with the treatment choice for the degenerative spondylolisthesis vignette (p < 0.05) (V3). Years in practice was significant for insufficiency fracture (V4).

For the insufficiency fracture (V4), surgeons in practice for < 10 years were more likely to select the minor procedures of kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty than analgesia and brace, whereas those with more than 10 years of experience were more likely to select the conservative analgesia and brace than the minor surgical procedures. This also supports Mroz et al.’s (2014) finding that younger surgeons were more likely to select more complicated procedures. The pattern could be indirectly linked to changes in training, though we cannot say this with certainty; it may simply be that, with experience, surgeons learn that the more conservative analgesia and brace and mobilize may be sufficient for an elderly patient with an insufficiency fracture.

External funding/influence

Financial incentives may explain the differences between the treatment choices of surgeons working in the public and private sectors [8]. Public and private funders are becoming more influential in surgical decisions [2]. Hussain et al. (2011) also identified resource availability as an influencing variable [13].

Surgeons who were designated service providers (DSPs) and/or working part or full time in the public sector tended to select conservative treatments rather than minor or major surgery for the distractive flexion injury of the cervical spine (V1) and the insufficiency fracture (V4). For the distractive flexion injury, surgeons who were DSPs were more likely to select the conservative collar or skeletal traction treatments than any of the major surgery fusion options. Health insurers set up DSP networks in attempts to curtail costs. They may have stricter criteria for what surgery they will cover, which may encourage surgeons to select a conservative treatment as their first choice.

For the insufficiency fracture (V4), surgeons working part or full time in the public sector were more likely to select the conservative analgesia and brace option than surgeons working only in the private sector. Of those working at least partly in the public sector, 73% selected analgesia and brace compared to only 42% working full time in the private sector. The resource pressure on the public sector means that surgeons working in that sector are unlikely to recommend surgery when a conservative treatment option is available.

Strengths and limitations

It is acknowledged that the survey was conducted at a single congress, which may be perceived as a limitation. The South African Spine Society Congress is the largest dedicated assembly of spine surgeons in our setting, and it is unlikely that conducting the survey at additional events would have notably increased the sample size. The study also performed multiple comparisons without adjustment for familywise errors, so the findings are exploratory only. Nevertheless, the study contributes to limited existing knowledge on treatment variation and supply-side factors that influence surgeon variation in the treatment of spinal pathologies, and it may help further research in this area.

Conclusion

Understanding the extent of treatment variation and the surgeon characteristics associated with this variation is an important first step in identifying the most effective treatment and then creating greater uniformity based on value. A subsequent study with preplanned hypotheses should be conducted to confirm the observed associations with caseload, years in practice and training and external funding. However, this study’s findings make a case for an evaluation of outcomes and costs to identify value-based care in developing countries like South Africa. Such research could help countries that are implementing national health systems and seeking to contract with providers on value.

Greater uniformity in treatment and easily accessible outcomes reporting would guide patients and reduce the amount of conflicting information they receive. Insurers who contract on value based on sound research can guide the patient in this regard. Finally, further investment in training and participation in fellowship programs may be necessary, along with greater dissemination of information from studies in literature.

References

Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, Bronner KK, Fisher ES (2006) United States’ trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992–2003. Spine 31(23):2707–2714. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000248132.15231.fe

Debono B, Lonjon G, Galovich LA, Kerever S, Guiot B, Eicker S, Hamel O, Ringel F (2018) Indication variability in degenerative lumbar spine surgery: a four nation survey. Spine 43(3):185–192. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002272. (PMID: 28604486)

Irwin Z, Hilibrand A, Gustavel M, McLain R, Shaffer W, Myers M, Glaser J, Hart R (2005) Variation in surgical decision making for degenerative spinal disorders part II: cervical spine. Spine 30(19):2214–2219. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000181056.76595.f7. (PMID: 16205349)

Lurie J, Tomkins-Lane C (2016) Management of lumbar spinal stenosis. BMJ 352:h6234. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h6234

Irwin Z, Hilibrand A, Gustavel M, Mclain R, Shaffer W, Myers M, Glasser J, Hart R (2005) Variation in surgical decision making for degenerative spinal disorders Part 1: lumbar spine. Spine 30(19):2208–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000181057.60012.08

Mroz T, Lubelski D, Williams S, Rourke C, Obuchowski N, Wang J, Steinmetz M, Melillo A, Benzel E, Modic M, Quencer R (2014) Differences in surgical treatment of recurrent lumbar disc herniation among spine surgeons in the United States. Spine J 14:2334–2343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.01.037. (PMID: 24462813)

Alvin M, Lubelski D, Alam R, Williams S, Obuchowski N, Steinmetz M, Wang J, Melillo A, Pahwa A, Benzel E, Modic M, Quencer R, Mroz T (2018) Spine surgeon treatment variability: the impact on costs. Glob Spine J 8(5):498–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568217739610.PMCID:PMC6149049. (PMID: 30258756)

Lubelski D, Williams S, O’Rourke C, Obuchowski N, Wang J, Steinmetz M, Melillo A, Benzel E, Modic M, Quencer R, Mroz T (2016) Differences in surgical treatment of lower back pain among spine surgeons in the United States. Spine 41(11):978–986. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001396. (PMID:26679881)

Parker Scott L, Chotai Silky, Devin Clinton J, Tetreault Lindsay, Mroz Thomas E, Brodke Darrel S, Fehlings Michael G, McGirt Matthew J (2017) Bending the cost curve—establishing value in spine surgery. Neurosurgery 80(3S):S61–S69. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuros/nyw081

Competition Commission (2019) Health market inquiry: Final findings and recommendations report. In September 2019. Competition Commission, Pretoria

Lonjon G, Grelat M, Dhenin A, Dauzac C, Lonjon N, Kepler CK, Vaccaro AR (2015) Survey of French spine surgeons reveals significant variability in spine trauma practices in 2013. Orthop Traumatol Surgery Res 101:5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2014.10.018

Hussain Manzar, Nasir Sadaf, Moed Amber, Murtaza Ghulam (2011) Variations in practice patterns among neurosurgeons and orthopaedic surgeons in the management of spinal disorders. Asian Spine J 5(4):208. https://doi.org/10.4184/asj.2011.5.4.208

Birkmeyer John D, Reames Bradley N, McCulloch Peter, Carr Andrew J, Bruce Campbell W, Wennberg John E (2013) Understanding of regional variation in the use of surgery. The Lancet 382(9898):1121–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61215-5

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the South African Spine Society Executive Committee for allowing us to conduct the study at their annual conference. We are grateful for conference participants at the South African Spine Society Annual Conference (2022) and the African Health Economics and Policy Association (HfHEA) Conference (2022) for helpful comments. We also thank Prof. Daan Nel (Stellenbosch University Centre for Statical Consultation) for his statistical oversight. The work received a small contribution from the Stellenbosch Spinal Surgery Training Trust. However, the Trust was not involved in the study design; in collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the funders.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stellenbosch University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (reference number S20/10/291).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Survey

Factors associated with surgeons’ decisions when treating spinal problems.

Specialist information

1) What is your specialization?

-

Orthopedic surgeon

-

Neurosurgeon

-

Other (specify)

2) At which university did you complete your specialist training?

-

Cape Town (UCT)

-

Free State (UFS)

-

Witwatersrand (Wits)

-

Stellenbosch (SU)

-

KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN)

-

Sefako Makgatho

-

Walter Sisulu

-

Limpopo

-

Pretoria (UP)

-

Other

3) How old are you?

-

Under 30

-

30–39

-

40–49

-

50–59

-

60 or older

4) How long have you been in practice as a neurosurgeon/ orthopedic surgeon?

-

Less than 5 years?

-

5–9 years

-

10–19 years

-

More than 20 years

5) How much of your time is spent treating patients in the public sector?

-

None

-

Part time

-

Full time

6) On average, how many spinal surgeries do you do per MONTH?

-

Less than 5

-

Between 6 and 10

-

Between 11 and 20

-

Between 21 and 30

-

More than 30

7) Are you a designated service provider for any medical scheme?

-

No

-

Yes

Vignette 1

26-year-old male hit back of head on edge of pool while somersaulting. No loss of consciousness. Scalp laceration and neck pain. No neurological deficit.

Choose your preferred treatment option

-

Collar

-

Skeletal traction

-

Anterior fusion procedure

-

Posterior fusion procedure

-

Combined anterior and posterior fusion procedure

Vignette 2

34-year-old high-level female athlete, triathlon participant. Lower back ache radiating to right lower limb (L5 distribution). No motor deficit. Four weeks intermittent non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and pregabalin. Unable to participate in sport.

Choose your preferred treatment option

-

Structured conservative treatment regime (multi-disciplinary)

-

Epidural or similar pain procedure

-

Microdiscectomy

-

Laminectomy

-

Decompression and fusion (posterior only)

-

Decompression and fusion (including interbody fusion)

Vignette 3

68-year-old female with back ache and radicular pain in L5 distribution on the right. Unable to sit for extended period (stood during entire consultation). 5/5 motor power – all.

Choose your preferred treatment option

-

Structured conservative treatment regime (multi-disciplinary)

-

Epidural or similar pain procedure

-

Laminectomy

-

Decompression and fusion (posterior only)

-

Decompression and fusion (including interbody fusion) posterior approach

-

Decompression and fusion (including interbody fusion) anterior approach

Vignette 4

Frail 88-year-old female living with 94-year-old husband. Severe axial back ache at thoracic lumbar junction for about two weeks. No specific trauma event. No significant known co-morbidity. No neurological deficit or symptoms. Pain improves when lying down. Son is a GP based overseas.

Choose your preferred treatment option

-

Analgesia/ brace and mobilize

-

Kyphoplasty

-

Vertebroplasty

-

Posterior instrumented fusion

-

Corpectomy, strutgraft and instrument fusion (combined anterior and posterior)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vorster, P.A., Burger, R., Mann, T.N. et al. Surgeon variation: a south african spinal pathology treatment survey. Eur Spine J 33, 2577–2593 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08295-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-024-08295-6