Abstract

Purpose

In treating cancer, different chemotherapy regimens cause chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN). Despite recent international guidelines, a gold standard for diagnosis, treatment, and care is lacking. To identify the current clinical practice and the physicians’ point of view and ideas for improvement, we evaluated CIPN care by interviewing different specialists involved.

Methods

We performed semi-structured, audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded interviews with a purposive sample of oncologists, pain specialists, and neurologists involved in CIPN patients’ care. Data is analyzed by a constant comparative method for content analysis, using ATLAS.ti software. Codes, categories, and themes are extracted, generating common denominators and conclusions.

Results

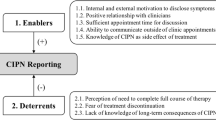

With oncologists, pain specialists, and neurologists, nine, nine, and eight interviews were taken respectively (including three, two, and two interviews after thematic saturation occurred). While useful preventive measures and predictors are lacking, patient education (e.g., on symptoms and timely reporting) is deemed pivotal, as is low-threshold screening (e.g., anamnesis and questionnaires). Diagnosis focusses on a temporal relationship to chemotherapy, with adjuvant testing (e.g., EMG) used in severe or atypical cases. Symptomatic antineuropathic and topical medication are often prescribed, but personalized and multidimensional care based on individual symptoms and preferences is highly valued. The limited efficacy of existing treatments, and the lack of standardized protocols, interdisciplinary coordination, and awareness among healthcare providers pose significant challenges.

Conclusion

Besides the obvious need for better therapeutic options, and multidisciplinary exploration of patients’ perspectives, a structured and collaborative approach towards diagnosis, treatment, referral, and follow-up, nurtured by improving knowledge and use of existing CIPN guidelines, could enhance care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With advances in the treatment of cancer, the length of survival increases, and more patients live with long-term side effects. This emphasizes the importance of a focus on these side effects as well as quality of life (QoL) besides cancer curation [1,2,3]. One chronic side effect and major dose-limiting toxicity of chemotherapy treatment (e.g., not only platinum-, taxane, and vinka-alkaloid based, but also newer substances) is chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) [4,5,6,7]. It presents as a persistent peripheral, “stocking-and-glove” distributed neuropathy affecting 13–79.2% of patients to a variable extent after 15 months [8,9,10].

An insurance claim data study including 53 million patients found a relative underrepresentation of the incidence of CIPN as compared to large clinical studies. This is possibly explained by a lack of an evidence-based approach resulting in a failure to report [10].

CIPN may present diagnostic issues (e.g., no golden standard) in its primary identification. Evidence-based proven treatment and follow-up strategies are lacking, although recent American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [11] and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [12] guidelines on CIPN provide some framework. Our hypothesis is that standardization of the diagnosis and treatment of CIPN, and implementation of existing guidelines, might be suboptimal but mandatory to improve CIPN care and QoL. In acquiring the best reflection on the majority of CIPN patients and common complaints, and in the context of the Dutch healthcare organization, we interviewed accredited oncologists, neurologists, and pain specialists to gain insight in how different specialists approach CIPN care. We explored their views on healthcare organization and patient specific CIPN care as well as opinions on needed improvements.

Methods

This explorative qualitative study with semi-structured interviews was performed after approval by the local research ethical committee (METC Amsterdam UMC (VU), The Netherlands, dossier number: 2021.0069).

Participants

Registered oncologists, neurologists, and pain specialists, involved in the care for patients with CIPN, were invited to participate in this interview study. Written (e-mail) and oral information was provided (practical, on anonymity, on withdrawal) and informed consent for participation and publication was obtained before any actual interview. Recruitment of participants continued until thematic saturation was achieved per specialty, after which at least two more interviews were performed. Per specialty, eight to nine interviews were conducted, with a total of 26.

Procedure

Data was collected by semi-structured interviews, starting from a topic list as presented in Table 1 and a first general question: “Could you talk about your involvement in the care for patients with CIPN?” As the interview progressed, participants were asked to elaborate on the topics and as new ones arose, topics were added. Questions were open-ended and broad, allowing description of experiences without being overly structured by the guide, asking participants to elaborate on topics in the updated list. Each participant was interviewed once, either through Microsoft Teams (Microsoft, www.microsoft.com) or Zoom Video Conference (Zoom Video Communications, www.zoom.us) to the interviewee’s preference. Researchers FH, BW, and NB are medical doctors (MD) receiving additional training to the conduct of these semi-structured interviews, in addition to their regular extensive communication training.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and entered into Atlas.ti Software v.23.1.1 (http://atlasti.com Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Gestures, pauses, perceived hesitations, and notable changes in tone of voice and emphasis were included as notes in the transcription, after which the video file was deleted, and the audio file saved as part of the electronic case report form. Data collection, coding, and analysis started after a specific interview was completed, so these phases occurred simultaneously as the study progressed. Qualitative data was analyzed by an inductive process, using a constant comparative method for direct content analysis, generating direct information from participants without imposing preconceived categories after open coding and using codes from previous interviews as a starting point for the following [13]. Two researchers periodically discussing findings and discrepancies, referring to the data as needed until complete agreement was reached. Analysis progressed through an iterative process of reducing data into categories and themes.

Results

Sample

Interviews were conducted from January 2021 to June 2023. As mentioned, after thematic saturation occurred, at least two additional interviews were conducted to strengthen the conclusion. Accordingly, the number of interviews conducted was 6 + 3 = 9 for medical oncologists, 7 + 2 = 9 for pain specialists, and 6 + 2 = 8 for neurologists. In two additional interviews with oncologists, one new code came up, and a third additional interview was conducted. Interviews lasted 21 to 30, 23 to 50, and 16 to 33 min for oncologists, pain specialists, and neurologists, respectively. The participants’ characteristics are presented in Table 2. Quotes, numbered as [quote N°] in the results text, are displayed in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Medical oncologists

In total, 37 descriptive codes were extracted from the data after coding, divided into nine categories, and subdivided into five themes. A schematic overview of codes, categories, and themes is provided in Table 3.

Theme 1: Prevention

Lacking evidence of efficacy, preventive measures are rarely used in CIPN, excluding general advice (quotes 1–3). Pre-existing peripheral neuropathy (e.g., diabetic or alcoholic) influences the oncological treatment plan, while risk factors are only a reason for specific actions or referral for some (quotes 4–8). A need for useful predictors is emphasized (quotes 9–10).

In some cases, you stop the treatment and ask yourself: ‘did I stop to early?’ and in other cases when a patient develops symptoms you think: ‘why didn’t I stop earlier?’ (quote 10).

Informing patients and expectation management are deemed vital and are provided orally by the oncologist and specialized nurses supplemented with written information. It includes (uncertainties on) symptom development and “coasting” (increasing symptoms after chemotherapy cessation) (quotes 11–13).

Theme 2: Assessment

All oncologists perform a brief (verbal) screening on pre-existing peripheral neuropathy and risk factors before each chemotherapy cycle, sometimes referring to a neurologist when present (quote 14). Reporting CIPN symptoms is actively encouraged, improving follow-up, and thus detecting neurotoxicity earlier (quotes 15–16). For CIPN grading, the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCae) is used, most commonly when further assessing symptoms (14) (quotes 17–18, 24–25). Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) questionnaires are only used in the context of clinical studies (quotes 19–20). In uncertainty, consulting a neurologist and change in chemotherapy-regimen are considered (quotes 26–28).

Follow-up regarding side effects differs after adjuvant chemotherapy (mainly by the surgeon) and after chemotherapy in metastasized disease (mainly by the oncologist), for patients with severe symptoms of CIPN and in a palliative setting (the oncologist or nurse practitioner) (quotes 21–23).

Theme 3: Therapy

Symptomatic treatment is usually started for pain and/or poor sleep quality, using amitriptyline, nortriptyline, pregabalin, and gabapentin, but not duloxetine (quotes 29–31). Because of side effects or insufficient effect, half the patients stop taking this medication in time (quote 34). Non-pharmacological advice is practical and involves foot care, avoidance of painful stimuli (e.g., cold prevention), or support in coping (quotes 35–36).

Reduced initiation doses are a strategy in pre-existing peripheral neuropathy or in a distinct wish to preserve fine motor skills. Complex cases are discussed among colleagues (quotes 37–39). Later dose reduction is usually protocolized, 25% (in neurotoxicity grade ≥ 2) up to 50% (quote 40), and determined by chemotherapy goal (adjuvant or palliative, impact on survival) or pre-existing neuropathies. Side effects are accepted as being (partially) inevitable, and thus must be embedded in the informed consent (quotes 41–45).

Theme 4: The healthcare system

Knowledge on existing diagnostic and treatment algorithms is scarce (quote 46). Algorithms are partially embedded in (local) treatment protocols, but do not assist in diagnosing and treating CIPN (quotes 47–49). Information on side effects is individually registered, but no national database collecting risk factors and outcome-related (scientific) data exists (quotes 50–51).

General practitioners contact the oncologist in case of general side effects or CIPN, and its treatment (quote 52). If symptomatic treatment fails or in high grades of neurotoxicity, neurologists, pain specialists, or subspecialized neuro-oncologists are involved (quotes 53–54) as are occupational therapists, physiotherapists, and/or podiatrists for practical advice and support in coping (quotes 55–56).

Theme 5: Areas of improvement

Improving awareness and attention for CIPN is regarded essential in improving CIPN care. Therefore, available epidemiological data treatment options should be improved (quotes 57–59).

I think that it can be a good start to gather more information of our own patients so that we can perform more epidemiological studies on Dutch patients. With that we can also create some more awareness I hope. (quote 58).

Also, a certain exposure or experience with chemotherapeutic agents benefits early recognition of CIPN symptoms (quotes 60–61), as well as standardization of diagnosis and treatment (quote 62). New and more effective strategies in the prevention and treatment of CIPN would be welcomed, as well as less (neuro)toxic oncological regiments (quote 63).

Neurologists

In total, 66 descriptive codes were extracted from the data after coding, divided into 16 categories, and subdivided into six themes. A schematic overview of codes, categories, and themes is provided in Table 4.

Theme 1: The organization of healthcare

The organization of (multidisciplinary) care depends on local possibilities and patient influx. While sub-specialization and the exchange of ideas is encouraged, the case load is usually spread random. Most are involved through neuro-oncological expertise, within existing neuro-oncological or palliative care meetings and random (ad hoc) consultation, as no specific CIPN meetings exist. Although reimbursement concerns seem minor, opinions differ on the value of the time and effort put into frequent patient visits and additional testing. There is a perception of randomness in policies for referral, diagnosis, and treatment, varying per oncologist, tumor site, chemotherapy regimen, and clinical picture, highlighting the need for structured frameworks (quotes 64–65).

I think variation is large. This does not necessarily have to be wrong; some doctors feel more comfortable starting specific treatments than others. But a framework, some agreement… who will start treatment, which patient needs a neurologist or a pain physician… Yet then, what exactly is the best treatment? To my opinion, even that is not certain. So, something practical: who, what, when? That, I would welcome. (quote 64).

The impression is that the oncologist usually starts CIPN treatment, assuming an expectation of limited additional diagnostic or treatment options on referral.

Because I can imagine that oncologists do not refer patients to us, claiming we do not add much. Which, unfortunately, for some patients, is true. (quote 66).

The neurologists’ added value concerns functional aspects and specific skills in (indicating) specific testing and differential diagnosis, but not analgetic drug prescription specifically. Referral questions regard chemotherapy (e.g., discontinuation, optimalization of concurrent problems, follow-up), diagnosis, or the need for additional testing by EMG, or are study-related, and less frequent to justify dose reduction. Follow-up is done by the specialist prescribing pain medication (quote 67).

Theme 2: Risk factors and confounding diseases

After screening for additional risk factors, an EMG is incidentally requested for diagnosis and follow-up, but only in research at baseline. Its predictive value for the evolution and prognosis of CIPN complaints is regarded low. For the exclusion of co-morbidity causing neuropathy, blood tests are often done according to the Dutch neurologists’ guidelines [14], but one participant criticizes the weight given to mildly divergent (not clinically relevant) lab results and its implications.

Theme 3: Treatment (in)possibilities

Pregabalin is the first choice for all but one, followed by tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) or duloxetine (parallel made with diabetic polyneuropathy) with no apparent preference. Nortriptyline is generally preferred over amitriptyline because of its side effects profile. In case of a circumscribed area of pain, capsaicin is used. Gabapentin, cannabinoids, other topical drugs, and opioids are incidentally prescribed.

Essential and individual patient education (on pain), coaching, self-sustainability, and recommending physical activity are sometimes reinforced by rehabilitation (daily problems and suffering), physical, occupational, and/or psychological therapy (anxiety and depression symptoms) (quote 68). This concerns existential issues, managing chronic disease and cancer, acceptance, and “creating a positive vicious circle” (quote 69). However, there is a shared frustration in seeing patients, having (had) cancer treated, now being disabled consequently, without sufficient treatment results.

By not thinking: ‘everything is always so painful’, but being active, keeping up activities, finding distraction and creating something of a positive vicious circle. Trying to improve energy levels, experiencing success, alleviating the experienced burden. … How do you cope with pain, which probably will not fade away totally, an aspect you should give attention to, improving acceptance, and probably giving space for improvements with our treatments (quote 69).

Theme 4: Socio-environmental aspects

Social and work-related issues are mentioned as a reason for further diagnostic efforts, although not yielding more therapeutic options (quote 70).

Most statements overlap with “theme 3 – treatment (im)possibilities.” The strategy in starting and increasing medication, coaching, creating options for self-sustainability, and weighing effects versus side effects are stated to be key in treatment success and patient satisfaction.

Theme 5: Diagnostic conundrums

In patients with pain, anamnesis (regarding any temporal relationship with chemotherapy cycles, distribution, comorbidities) combined with (specific) physical examination is regarded as sufficient by most. EMG is used in specific cases, regarded of little value in diagnosis and even less in predicting CIPN evolution. Questionnaires are not used. Interviewees are generally reluctant towards statements on the course of CIPN, especially in less used or newer chemotherapeutic agents, underlining the uncertain course and final state. (See also above “Theme 3.”).

Theme 6: Towards a proven standardized diagnosis and treatment

Scarce evidence on CIPN treatments results in preferences translated from the use in other neuropathic pain states. Three participants are researchers on anti-neuropathic drugs (partially in CIPN) or CIPN treatment specifically, recognizing trivial improvement in preventative, diagnostic, and therapeutic possibilities over the years. As mentioned, no specific local protocols exist resulting in variable CIPN care without notion of the scope of the problem, but blood tests are done according to the national neurologists’ guidelines. Participants are (all but one) unfamiliar with ASCO and/or ESMO CIPN guidelines, and thus do not apply them. Also here, some grip or framework for referral, diagnosis, and treatment is welcomed. Two participants participate in the development of national guidelines on (general) neuropathic pain.

Pain specialists

In total, 63 descriptive codes were extracted from the data after coding, divided into ten categories and subdivided into five themes. A schematic overview of codes, categories, and themes is provided in Table 5.

Theme 1: Treatment regimen

Generic, mainly local, and non-binding protocols are used in guiding CIPN treatment (quotes 71–72), prompting custom-made decisions depending on medical background, specific symptoms, and preferences (quotes 73–74). On referral, TCAs or gabapentin has often been used. Duloxetine is prescribed regularly as a first-choice alternative, and some prescribe anti-epileptics (e.g., pregabalin, gabapentin), while others dispute its value (quotes 75–77). Opioids are mainly used in a palliative setting, with general reluctance and varying ideas on its efficacy (quote 78). Occasionally, ketamine, cannabinoids, and other anti-neuropathic drugs are used (quote 79).

All subjects use capsaicin 8% patches, while other topical treatments (capsaicin 0.025–0.075%, lidocaine, phenytoin, and amitriptyline) are deployed to minimize adverse effects (quote 80). Some interviewees propagate the use of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), but variable effects are expected, with diffuse pain localization impeding its practical use (quote 81). Singularly mentioned and seldomly used were electroacupuncture, iontophoresis, virtual reality, and neuromodulation (quote 82). Often, a physiotherapist for movement-related aspects or podologist is consulted (quote 83).

Theme 2: Treatment-related issues

Pain specialists are not actively involved during chemotherapy, and few are consulted for general advice in a palliative care context (quote 84). Preventive measures and improved screening would be welcomed (quotes 85–87), expecting an underrepresentation, and secondary complaints are common in late referral (quotes 103–105). Oncological issues and eye on survival tend to overshadow negative consequences of chemotherapy. This prompts adequate patient education on CIPN characteristics (e.g., positive, and negative symptoms relating to treatment possibilities), its influence on QoL, the efficacy of treatment possibilities, and thus expectation management (quotes 88, 93–94, 115–116). According to the interviewees, patients are generally not surprised by CIPN complaints per se, but by its severity (quote 96). The oncologists’ CIPN awareness is deemed sufficient, but not for pain and its treatment specifically.

Well, there’s not enough awareness about pain in general, or about clinical pain management teams. Many people stay with their general practitioner, or are not referred to us… so no, I believe there’s insufficient awareness about pain and pain management in general. (quote 98).

Medical management is assisted by specialized nurses or physician assistants for specific interventions and guiding a stepped-care plan, in multiple low-threshold and often telephonic appointments (quotes 89–92). When stable, and in absence of treatment possibilities, patients are usually followed up by their general practitioner (quote 95). Evaluation of treatment is often done with pain intensity scores (quote 99). Most are not convinced of the superiority of any treatment over another because of huge varieties in effect, and limited comparative evidence (quote 100). New scientific evidence is welcomed, but usually regarded as disappointing (quotes 101–102), explaining why multidisciplinary approach (supplementary) care is valued higher (quote 106).

Neuroprotective interventions, new topical treatment options, and prevention by pre-emptive analgesia or other drugs are regarded valuable topics in future research (quotes 107–108).

While oncologists are generally regarded the primary healthcare provider for CIPN patients, and a case manager secures continuity, interdisciplinary aspects and specific knowledge within other specialties should be applied more appropriately (quotes 109–110).

Theme 3: Diagnosis

Reported symptoms and signs, in a temporal relation to chemotherapy treatment, are considered essential and usually sufficient for diagnosis without additional testing (quote 111). Neurologists are only involved in unusual and severe cases (quote 112). Questionnaires assessing the multidisciplinary aspects of pain are always used (quote 113).

On referral, all patients report typical peripheral neuropathy complaints, and some report secondary symptoms (quote 114).

Theme 4: Healthcare organization

Multidisciplinary consultations within pain clinics, though usually not CIPN specific and only occasionally involving oncologists and other professionals, are considered essential in CIPN care (quotes 117–118). Content with low-threshold impromptu consultation (e.g., by telephone) is good, but the level of cooperation between specialties is variable. Mutual visibility (e.g., involvement in each other’s meetings), case discussions, and crossing the boundaries of one’s super specialized knowledge, possibly improving CIPN awareness and care, is time-consuming and an organizational challenge (quotes 119–121). Case managers, and changing attitudes over the years, are factors pointed out to have already improved this, mainly in palliative care (quotes 122–123).

A clear cutoff point for referral cannot be defined and should be tailored. Involvement seems valuable in complex cases, or if topical treatment is indicated (quote 124). As stated, delays in referral are common (quote 125). For optimal personal care and continuity, the specialized nurses’ or case managers’ role should be improved (quote 126).

Theme 5: Personalized care

As stated, patient education and instructions, adequate management of expectations (also related to pre-existing functionality and activity level), and identifying confounding psychosocial factors (e.g., anxiety, coping strategies) are important (quotes 127–128), implying the importance of a multidimensional approach and shared decision making (quotes 129–131).

I think the right guidance and education is crucial, especially for neuropathic pain, because success rates are so low. So, you really have to… patient empowerment is really important. (quote 127).

Having regrets after chemotherapy does occur, up to one request for euthanasia in intractable CIPN, but is usually perceived in the light of uncertainty on forehand (quotes 132–134).

Discussion

In this study, by interviewing multiple specialists with different expertise, we gain a broader insight in factors influencing cooperation, referral, diagnosis, and treatment. Concluding points of specific interest and common denominators, which form the basis for this discussion, are provided in Table 6.

Few published studies explore clinician and patient perspectives on the provision of care, information, and support. Their approach is mostly clinician- and oncology-centered, focusing on technical aspects and knowledge. In a study by Knoerl et al. [15], CIPN symptoms were discussed and documented in less than half of the encounters with patients at risk. There is evidence for the use of QLQ-CIPN20 and FACT/GOG-Ntx in a research setting, but data on the use of PROMs in a clinical setting is limited. While multiple studies found a lack of familiarity with CIPN in patients as well as clinicians, a study on the use of a web-based care planning system did not directly underline its necessity in identifying symptoms [15,16,17,18]. Also, CIPN diagnosis is not straightforward, no single method is advised over another in ESMO- and ASCO guidelines, and important regional differences in assessment, incidence, and prevalence occur [19].

Despite the wish for a “who-what-when-structure” in diagnostic (specific tests), treatment (evidence, regimen), and organizational (referring, follow-up) aspects, few local or national protocols are available and international guidelines are scarcely used. Delayed treatment or referral is encountered and most welcome early referral and interdisciplinary consultation, while some question its (cost-)effectiveness. To our opinion, better acquaintance with international guidelines could provide an obvious first step. In this context, attention for implementation and evaluation also seems important when publishing new guidelines. Secondly, focusing on organizational aspects, and national and regional protocols could be developed. Thirdly, better registration of complications including CIPN as suggested by multiple specialists could help identifying patients at risk, improve awareness, and identify shortcomings in current policy. A recent Delphi study among seven respondents on 18 statements within four themes (pre-treatment review, screening and assessment, management and referral, and CIPN path feasibility) regarding a new-developed clinical pathway recognized its value in CIPN care across different health services [20].

Diagnostic strategies vary, lacking a standardized approach. A fitting complaint pattern in temporal relation to chemotherapy suffices for most. Ideas on the use of rating scores (mainly in research and by oncologists) and more invasive tests (blood tests for co-morbidities and EMG, mainly by neurologists) were proposed. However, PROMs are not used in diagnosis. While their value is proven for some diseases and pain conditions, the clinical value in CIPN is less established [18, 21, 22].

The lack of treatment possibilities in painful CIPN is generally deplored, which influences clinical practice, for instance regarding anti-neuropathic drugs (no high hopes, NNT perceived as high) or referral (“what’s the use”?). Again, a structured approach is wished for. Treatment varies and is rated as “random,” influenced by personal experience or translation from evidence for other pain states, but usually consists of chemotherapy dose reduction or cessation (oncologists) and anti-neuropathic drugs (all specialties), while other (multidimensional) options are occasionally used. Acquaintance with topical treatment could possibly be improved, and the copying of a therapeutic approach/regimen from other neuropathic pain states and/or polyneuropathies raises the question whether this is adequate and cost-effective. For instance, only duloxetine is recommended in ASCO guidelines on CIPN, (partially) explaining therapy failure as described by several professionals (for instance in medical oncologists; thema 3: therapy, quotes 29–36). The consequences of changing the chemotherapy regimen can be profound. These matters fit patients’ wishes: a need for a focus on prevention instead of treatment, and a greater focus on non-pharmacological treatments. Also, the possible value of exercise in CIPN prevention is recognized yet under-utilized, whereas in ESMO and ASCO guidelines, supervised medical exercise as well as self-management interventions for treatment and even prevention are advised [11, 12, 21].

Opted ideas for improvement can be seen as starting points for future protocols, guidelines, and research [21]. Most feel a need for standardization in diagnostic, screening, and treatment approaches. A general need for better treatment options (medication or otherwise) is felt, but in general expectations are low (all specialties). Follow-up seems to be of a very “technical” nature, symptom driven, with little focus on QoL. The possibilities and value of a more multidisciplinary approach (e.g., psychological, multidimensional/rehabilitation, general guidance) should be further explored, as many specialists claim its value from the perspective of chronic pain and suffering (this study, 19).

Our study has some limitations. First, bias in selection of the interviewees is conceivable, due to recruitment within affiliated hospitals and professional network and an above average interest in the subject. Second, other specialists and the general practitioners participate in CIPN care. Their exposure however is probably limited, co-incidental, and variable, so that interviewing them might not yield representative results. Third, patients’ perspective and optimizing shared decision making other than merely providing information would be of interest [13].

In summary, interviewing different specialists generates a broad insight in the clinical approach of CIPN and differences between specialties. Key outcomes are displayed in Table 6, but foremost a structured approach towards diagnosis, treatment, referral, and follow-up is welcomed. This could partially be accomplished by improving knowledge and the application of existing (international) guidelines. For a clearer “who-what-when,” national and regional guidelines on CIPN specifically, instead of using those on other (neuropathic) pain states, could be developed. Interdisciplinary consultation and meetings are mentioned, but their value for all or specific CIPN patients is to be determined. In further research, besides better therapeutic options for CIPN, the patient perspectives, needs, and wishes should be explored.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2020) Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer J Clin 70(1):7–30

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) (2020) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2017. National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, based on November 2019 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/. Accessed Nov 2023

Tofthagen C (2010) Surviving chemotherapy for colon cancer and living with the consequences. J Palliat Med 13(11):1389–1391. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.0124

André T, Corrado B, Mounedji-Boudiaf L et al (2004) Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. New Engl J Med 350(23):2343–2351. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032709

Extra JM, Espie M, Calvo F et al (1990) Phase I study of oxaliplatin in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 25(4):299–303

Argyriou AA (2013) Clinical pattern and associations of oxaliplatin acute neurotoxicity: a prospective study in 170 patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer 119(2):438–444

Wilson HR (2002) Acute oxaliplatin-induced peripheral nerve hyperexcitability. J Clin Oncol 20(7):1767–1774

Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Kanai M et al (2008) Safety and efficacy of modified FOLFOX6 for treatment of metastatic or locally advanced colorectal cancer. A single-institution outcome study. Chemotherapy 54(5):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1159/000154921

Park SB, Lin CS, Krishnan AV, Goldstein D, Friedlander ML, Kiernan MC (2011) Long-term neuropathy after oxaliplatin treatment: challenging the dictum of reversibility. Oncologist. 16(5):708–16. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0248

Altaf R, Lund Brixen A, Kristensen B, Nielsen S (2014) E: Incidence of cold-induced peripheral neuropathy and dose modification of adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. Oncology 87:167–172. https://doi.org/10.1159/000362668

Loprinzi CL, Lacchetti C, Bleeker J, Cavaletti G, Chauhan C, Hertz DL, Kelly MR, Lavino A, Lustberg MB, Paice JA, Schneider BP, Lavoie Smith EM, Smith ML, Smith TJ, Wagner-Johnston N, Hershman DL (2020) Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 38(28):3325–3348. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.01399

Jordan B, Margulies A, Cardoso F, Cavaletti G, Haugnes HS, Jahn P et al (2020) Systemic anticancer therapy-induced peripheral and central neurotoxicity: ESMO-EONS-EANO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. Ann Oncol: Official J Eur Soc Med Oncol 31(10):1306–19

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 15(9):1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Vrancken AFJE, Notermans NC et al (2020) Revised Dutch guideline polyneuropathy: overview of recommendations. Tijdschr Neurol Neurochir 121(4):176–183

Knoerl R, Lee D, Yang J, Bridges C, Kanzawa-Lee G, Lita Smith G, Smith L (2019) Examining the impact of a web-based intervention to promote patient activation in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy assessment and management. J Canc Educ 18(1203):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-5093-z

Tanay MA, Robert G, Rafferty AM, Moss-Morris R, Armes J (2022) Clinician and patient experiences when providing and receiving information and support for managing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy a qualitative multiple methods study. Eur J Cancer Care 31(1):e13517. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13517

Taylor C, Tanay MA (2020) Assessing and managing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Cancer Nurs Pract 20(3):1–8. https://doi.org/10.7748/cnp.2020.e1717

Li T, Park SB, Battaglini E, King MT, Kiernan MC, Goldstein D, Rutherford C (2022) Assessing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy with patient reported outcome measures: a systematic review of measurement properties and considerations for future use. Qual Life Res 31(11):3091–3107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03154-7

Molassiotis A, Cheng HL, Lopez V et al (2019) Are we mis-estimating chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Analysis of assessment methodologies from a prospective, multinational, longitudinal cohort study of patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 19:132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-5302-4

Mizrahi D, Goldstein D, Kiernan MC, Robinson L, Pitiyarachchi O, McCullough S, Mendoza-Jones P, Grimison P, Boyle F, Park SB (2022) Development and consensus process for a clinical pathway for the assessment and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Support Care Cancer 30(7):5965–5974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07024-3

Dorsey SG, Kleckner IR, Barton D, Mustian K, O’Mara A, St. Germain D, Cavaletti G, Danhquer SC, Hershman DL, Hohmann AG, Hoke A, Hopkins JO, Kelly KP, Loprinzi CL, McLead HL, Mohile S, Paice J, Rowland JH, Salvemini D, Segal RA, Lavoie-Smith E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Janelsins MC (2019) The National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting for Prevention and Treatment of chemotherapy-induced Peripheral Neuropathy. J Natl Cancer Inst 111(6):531-537. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djz011

Alberti P, Rossi E, Cornblath DR et al (2014) Physician-assessed and patient-reported outcome measures in chemotherapy-induced sensory peripheral neurotoxicity: two sides of the same coin. Ann Oncol 25(1):257–264. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt409

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participating subjects for their time spent and effort gone into the participation in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by FH. The first draft of the manuscript was written by FH, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. A COREQ 32-item checklist is provided in Electronic Supplementary Material, on the reporting of aspects of the research team, study methods, context of the study, findings, analysis, and interpretations.

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This explorative qualitative study with semi-structured interviews was performed after approval by the local research ethical committee (METC AmsterdamUMC (VU), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, dossier number: 2021.0069). (See also the “ Methods ” section of the manuscript.)

Registered oncologists, neurologists, and pain specialists, involved in the care for patients with CIPN, were invited to participate in this interview study. Written (e-mail) and oral information was provided (practical, on anonymity, on withdrawal) and informed consent for participation and publication was obtained before any actual interview. (See also the “ Methods ” section of the manuscript.)

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

van Haren, F.G.A.M., Steegers, M.A.H., Vissers, K.C.P. et al. A qualitative evaluation of the oncologists’, neurologists’, and pain specialists’ views on the management and care of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in The Netherlands. Support Care Cancer 32, 301 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08493-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08493-4