Abstract

Purpose

To summarize the available evidence from systematic reviews with meta-analysis on the effects of music-based interventions in adults diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

An overview of systematic reviews was conducted. CINHAL, Embase, PEDro, PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library and Web of Science were searched from inception until November 2022. Systematic reviews with meta-analysis in individuals with cancer (any type), any comparator, and outcomes of cancer-related pain, fatigue, and psychosocial symptoms were eligible. The methodological quality of systematic reviews and the amount of spin of information in the abstract were assessed. The Graphical Representation of Overlap for OVErviews tool (GROOVE) was used to explore the overlap of primary studies among systematic reviews.

Results

Thirteen systematic reviews, with over 9000 participants, containing 119 randomized trials and 34 meta-analyses of interest, were included. Music-based interventions involved passive music listening or patients’ active engagement. Most systematic reviews lacked a comprehensive search strategy, did not assess the certainty in the evidence and discussed their findings without considering the risk of bias of primary studies. The degree of overlap was moderate (5.81%). Overall, combining music-based interventions and standard care seems to be more effective than standard care to reduce cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress. Mixed findings were found for other psychosocial measures.

Conclusion

Music-based interventions could be an interesting approach to modulate cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress in adults with cancer. The variability among interventions, together with important methodological biases, detract from the clinical relevance of these findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nearly 18 million individuals are diagnosed with cancer every year [1]. Cancer is, therefore, a major cause of morbimortality and will continue to impose for long the highest clinical and socioeconomic disease-related burden worldwide for a long time [2]. Patients with cancer face physical impairments during and after treatment, often associated with increased levels of pain and fatigue [3, 4]. In addition, the complex and uncertain course of the disease [5] also leads to psychosocial challenges [6], i.e., anxiety and depression [7]. Cancer treatments usually focus on disease recurrence [8] and ongoing physical symptoms [7]. Yet, people with cancer now demand a more person-centered and comprehensive approach [9] that can address mental health problems [8].

Non-pharmacological therapies are of interest for the clinical management of long-term diseases, as considered to be safe, low-cost, and with minor side effects [10]. Among them, music-based interventions have shown to be useful in chronic conditions to improve the physical and emotional well-being in individuals with fibromyalgia [11] or affective disorders [12] and seem to help to modulate cancer-related symptoms [13,14,15,16]. Music-based interventions can be categorized as ‘music medicine’, i.e., passive listening of recorded music offered by healthcare staff, or ‘music therapy’ that encompasses the clinical use of music in all its forms, as provided by a credentialed therapist [16, 17]. Although both terms are often interchanged [18], a clear distinction is that music therapy involves individualized assessment, intervention, and evaluation, and a patient-therapist relationship that develops through the music [19]. Music-based interventions are characterized for using music in a passive or interactive modality (engaging a patient to create live music) and can be applied alone or within a multimodal program [16, 20,21,22,23,24]. Music is a highly structured language that engages complex cognitive, affective, sensory, and motor control processed in the human brain [25, 26]. Listening to music can reduce the activity of the autonomic nervous system, and improve the synchrony of the neural firing, which promotes brain plasticity [27]. Music can also appeal to strong emotional and social responses [28]. This provides a neural basis for the biological impact of music [29] and its influence on the physical and mental health[30]. Several systematic reviews have recently investigated the effectiveness of music-based interventions in cancer care [31, 32]. An overview of these systematic reviews can provide a high-level synthesis of evidence [33, 34]. It can also address the transparency of information and the methodological biases of previous research [34, 35], which may help to understand the clinical relevance of current evidence. The aim of this overview was to gather and assess the available evidence from systematic reviews with meta-analysis on the effectiveness of music-based interventions on physical and psychosocial outcomes in adults diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

The overview protocol was prospectively registered at the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Y67BU). This overview has followed the preferred reporting items for overviews of reviews (PRIO) statement and the PRISMA for abstracts [36, 37]

Deviations from intended protocol

There were no major deviations from the registered protocol.

Search strategy

One researcher (ATM) carried out an electronic search from inception to November 2022 in the following databases: CINHAL, Embase, PEDro, PubMed, Scopus, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms associated with the intervention (music) and the medical condition (e.g., cancer, neoplasm) were combined. A comprehensive search strategy was first constructed for PubMed and then adapted for other databases. The lists of references of previous overviews were manually checked. The detailed search strategies are listed as Supplementary file A.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were established following the PICOs framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study):

-

P: Adults diagnosed with cancer without restrictions in body location/system or the cancer stage.

-

I: music-based interventions, used alone or as adjuvant to usual or standard care

-

C: no restrictions regarding the control intervention.

-

O: physical (e.g., pain, fatigue), and psychosocial measures (e.g., anxiety, depression, mood, distress, and quality of life).

-

S: systematic reviews with meta-analysis [38].

Systematic reviews were not included when: a) the publication was written in a language other than Spanish or English; b) there were not meta-analyses for the condition of interest; c) music-based interventions were meta-analyzed together with other experimental treatments; and d) meta-analyses included non-adult participants, population without cancer, or non-randomized controlled trials. Possible outcomes of interest that were not analyzed in at least two systematic reviews were not considered. Congress proceedings, thesis dissertations, and network meta-analyses were also excluded.

Study selection

Duplicate records were removed using the Mendeley desktop software, v2.72.0. and manually checked. One researcher (ATM) screened the remaining records based on the title and the abstract. The full text of eligible studies and those lacking an abstract were then revised. A consensus was achieved for three studies with a second researcher (AMHR) who independently double-checked the entire selection process.

Data extraction

Data were extracted with a standardized form that included: a) first author plus et al., the year of publication, and the number of clinical trials of interest; b) sample size (total and the experimental group); c) the characteristics of participants (age, sex, type of cancer); d) description of the experimental and control interventions; e) music style used; f) outcome measures; and g) main results from meta-analysis. We aimed to extract the overall effect size from each meta-analysis. When this was not reported, results from sub analyses were included. Two corresponding authors were contacted by e-mail to clarify some information [39, 40]. A reminder was sent, if necessary, one week after the first message. None of those contacted responded.

Methodological quality

Two independent reviewers (ATM and MJCH) evaluated the methodological quality of systematic reviews using the AMSTAR-2 tool [41]. As recommended, individual ratings of the 16 items were not combined to obtain an overall score [42]. Instead, the attention was given to critical weakness domains, namely: item 2, prospective review protocol; item 4, comprehensive search strategy; item 7, justification of the excluded studies; item 9, risk of bias; item 11, appropriateness of statistical analysis; item 13, interpretation of results based on the risk of bias; and item 15, publication bias [42].

Spin in abstracts of systematic reviews

The abstracts of the systematic reviews were assessed in isolation to quantify the occurrence of spin of information. Two independent reviewers (ATM and PGG) utilized a 7-item checklist [43], where each item was assigned a score of ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Data synthesis

Findings have been narratively described based on the outcomes of interest. To identify the most relevant key terms across systematic reviews, the VOSViewer software, v. 1.6.18 (Leiden University, The Netherlands) was used to conduct a co-occurrence analysis and bibliometric mapping. The degree of overlap of primary studies among included systematic reviews was evaluated with the Graphical Representation of Overlap for OVErviews (GROOVE)[44]. The GROOVE tool provides a simple, graphical and comprehensive representation, including the number of overlapped and non-overlapped primary studies and the overall assessment of the “Corrected Covered Area” (CCA), along with the CCA value for each pair of systematic reviews. For the CCA, the degree of overlap is considered to be slight (0–5%), moderate (6–10%), high (11–15%), and very high (CCA > 15%) [45]. Additionally, the CCA was measured taking into account chronological structural missingness, i.e., when primary studies were published after a systematic review [44].

Results

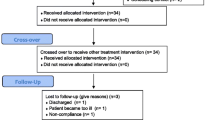

Search strategies retrieved a total of 926 eligible records. After removing duplicates, 466 records were screened. We eventually included 13 systematic reviews and 34 meta-analyses in the qualitative synthesis (Fig. 1). A list including the reports excluded during the final screening phase (n = 29) is described in the Supplementary file B.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included systematic reviews [39, 40, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. The most common types of cancer were breast and haematological, i.e., lymphoma and leukaemia. Music-based interventions were often combined with specific cancer treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy) or with standard or usual care, and involved passive listening of live or recorded music or patient’s active engagement (e.g., singing, clapping, and guided music imagery). Different music styles, selected by therapists or patients’ preferences, were used. A 23% of systematic reviews judged the overall certainty in the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [49, 55, 56]. Most reviews (77%) assessed the risk of bias of the clinical trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

Methodological quality

Results for the AMSTAR 2 tool are described in Table 2 (inter-rater agreement, 78.8%). The most important methodological concerns were ‘the lack of comprehensive search strategies’, ‘no information of the excluded studies’, and the ‘interpretation of the review findings without accounting for the risk of bias of primary research’. More than 90% of systematic reviews did not inform of why they included a certain type of study design or about their funding sources.

Spin of information in abstracts

The overall spin-abstract score was 21, with a mean value of 1.6 ± 1.3 points (inter-rater agreement, 79%). The most common forms of spin were ‘concluding a positive effect despite high risk of bias of primary trials’ (n = 7), and ‘selective reporting or overemphasis on the beneficial effect of music-based intervention’ (n = 5). No spin of information was found in three abstracts [46, 47, 52] (Supplementary file C).

Co-ocurrence analysis

Twelve out of the thirteen systematic reviews were included in the co-occurrence analysis (Figs. 2 and 3). One review did not include key terms [56]. The pattern of association between keywords has been reflected in the network and density visualizations The terms most frequently used were related to the research design (meta-analysis, systematic review), the intervention (music interventions, music), and the disease (cancer, neoplasms).

Overlapping between primary study

A total of 202 primary studies were identified across the included systematic reviews, out of which 119 were distinct studies. The overall overlap for the entire matrix of evidence was moderate (CCA = 5,81%) and this remained moderate (CCA = 6,92%) even after adjusting for chronological structural missingness. The citation matrix and the CCA calculation can be found in Supplementary file D. The Supplementary file E presents the graphical representation of the GROOVE tool. Three primary studies from one of the systematic reviews could not be retrieved due to the insufficient information and a lack of response from the corresponding author [39].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related pain

All systematic reviews measuring pain as an outcome (n = 6) concluded that music-based interventions plus usual or standard care were more effective than control interventions (e.g., usual or standard care, wait-list, bed rest, or wearing headphones with no music) to reduce cancer-related pain [39, 46, 48, 49, 52, 56].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related fatigue

Among the five systematic reviews assessing cancer-related fatigue, four of them indicated that combining music-based interventions with usual or standard care could yield more benefits than control interventions to improve cancer-related fatigue [39, 50, 54, 56]. However, one systematic review found no differences between groups [49].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related anxiety

Inconclusive conclusions were detected upon evaluating the six systematic reviews assessing cancer-related anxiety [40, 47, 49, 51, 55, 56].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related depression

Inconclusive conclusions were detected upon evaluating the seven systematic reviews investigating cancer-related depression [39, 40, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related mood and distress

Two systematic reviews concluded that music-based interventions together with usual or standard care could be more effective than controls in reducing cancer-related distress [49, 56]. However, findings on patients’ mood varied across studies [49, 56].

Music-based interventions on cancer-related quality of life

Two out of the three systematic reviews on quality of life demonstrated that music-based interventions combined with usual or standard care were superior to usual care alone in improving health-related quality of life [55, 56], while one review found no significant differences between groups [49].

Adverse events of music-based interventions

Four systematic reviews provided information regarding potential adverse events. In all of these reviews, no adverse events were observed following music-based interventions [46, 50, 52, 56].

Discussion

This overview summarized the evidence from systematic reviews with meta-analysis on the effects of music-based interventions to modulate cancer-related symptoms in adults. Overall, our results seem to suggest that adding music interventions to usual or standard care could be more beneficial than usual care alone to reduce cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress. On the other hand, findings were inconclusive for anxiety, depression, mood, and quality of life.

The present results expand those of previous overviews underlying the importance of including music-based within a multimodal treatment to decrease cancer-related pain [33, 57]. However, this is the first overview specifically focused on music-based interventions. Music involves cognitive engagement and distraction [58, 59]. Listening to music can help to the release of endogenous opioids and dopamine [58], which supports music-induced analgesia and may contribute to reduce the severity of fatigue [54]. Cancer-related pain is a complex, evolving, and multifaceted phenomenon [60], comprised of several dimensions (sensory. discriminatory, emotional, cognitive, and behavioral) [61]. Complementary integrative therapies, such as music-based interventions, can effectively manage cancer pain [61]. However, music may exert distinct influences on the different dimensions of pain, thus contributing to divergent findings observed in both physical and psychological measures. The impact of music on cancer-related fatigue has found to be highly relevant when music is combined with other therapies, e.g., exercise, especially when the intervention involves active patient’s engagement [50]

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of music to manage the cancer-related psychological burden during and after treatment [62, 63]. However, the exact mechanisms to understand how music engagement contributes to mental health remain unknown [64]. We found inconclusive results for anxiety, depression, mood, and the quality of life. This is in line with prior findings reported in palliative cancer care [65], but contradicts those for non-adult cancer populations [66, 67]. This might be because children and adolescents with cancer do not have as many comorbidities as adults and often tend to respond better to treatment. The style of music, along with personality, cultural, and contextual factors have an influence on the effects of music [64, 68]. Also, the diversity of tools used to measure anxiety and depression may contribute to the inconsistency of results [68]. In summary, more definite conclusions could be drawn with less heterogeneity in participants’ characteristics, especially age and cancer stage, assessment tools, and music intervention protocols.

Clinical relevance

This overview provides an updated synthesis of evidence about the use of music as an adjuvant therapy for adults in cancer care. Given that music is a potential cost-effective intervention [58], the present findings seem to encourage clinicians to implement its use into daily practice. There are, however, barriers that need to be overcome, mostly related to the lack of practical guidelines for music dose and timing [69]. Researchers have a strong responsibility to provide a complete description of interventions. That is the sole purpose of the TIDieR checklist, designed to advance evidence-based clinical practice [70]. However, none of the included systematic review provided information about how well described music-based interventions were in primary trials, which detracts from their replicability. Other important aspects should be born in mind. First, a clear distinction between music medicine or music therapy can be clinically relevant but it was only made in two of the systematic reviews [55, 56]. Music therapy was superior to music medicine to improve the quality of life and fatigue [56], but worse than music medicine for reducing anxiety [55]. These results suggest that the person who conducts the intervention and the mode of delivery may be clinically relevant. Second, treatment benefits following music interventions may depend on patients’ characteristics, e.g., emotional vulnerability [71]. Third, the lack of adverse effects suggests that music is a safe intervention in this population, although information regarding potential adverse events was only reported in four systematic reviews [46, 50, 52, 56]. Finally, most systematic reviews did not clarify whether ‘standard’ or ‘usual’ care included supportive cancer care, as a paradigm for modern treatment in oncology [72], to manage the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients [73], or specific cancer treatments such as chemotherapy. This needs to be clarified in future systematic reviews.

Methodological concerns

We have addressed, for the first time, potential biases, and transparency of information of systematic reviews in this field. The main concerns were related to the search strategy and the interpretation of the results without accounting for potential risk of bias. This may lead to selection bias and to an inaccurate translation of the findings to the clinical setting. It is somehow concerning that 40% of the reviews ‘overemphasized’ the beneficial impact of the music intervention group. Unfortunately, this misleading presentation of results is not new in the context of cancer treatment [74]. The certainty in the evidence using the GRADE framework was only evaluated in three systematic reviews [49, 55, 56]. In addition, as previously stated, the presence of adverse events, which is highly relevant, was poorly reported. Both aspects need to be carefully considered to improve the standard of quality. We incorporated chronological structural missingness to calculate the degree of overlap with the GROOVE tool, which is a novel and interesting approach. The GROOVE may also enable the analysis of overlap for specific outcomes, but this feature was not considered due to the high heterogeneity of measurement tools among the included reviews. Finally, evidence from clinical trials need to be complemented by qualitative studies to get a whole idea of music as individualized therapy.

Limitations

Literature search screening was conducted by a single researcher. Congress proceedings, network meta-analysis and reviews not written in Spanish or English were excluded, thus meaningful information may have been overlooked. The PICOs question considered music-based interventions in general and was not limited to music therapy or music medicine. In addition, the overlap of clinical trials among reviews prevented us to conduct meta-meta-analysis or to evaluate the certainty in the evidence.

Conclusions

Based on our results, we can conclude that:

-

The combination of music-based interventions with standard or usual care could be more effective than standard care alone to reduce cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress in adults diagnosed with cancer.

-

The additive effect of music-based interventions to standard or usual care remains uncertain for anxiety, depression, mood, and the quality of life.

-

Clinical and methodological concerns have been discussed and should be carefully considered when interpreting our findings in a clinical context.

Data availability

The data that support the study findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

05 April 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08478-3

References

Kocarnik JM, Compton K, Dean FE et al (2022) Cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life years for 29 cancer groups from 2010 to 2019. JAMA Oncol 8:420. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.6987

Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G (2019) Current cancer epidemiology. J Epidemiol Glob Health 9:217–222. https://doi.org/10.2991/jegh.k.191008.001

Evenepoel M, Haenen V, de Baerdemaecker T et al (2022) Pain prevalence during cancer treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 63:e317–e335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.011

Ma Y, He B, Jiang M et al (2020) Prevalence and risk factors of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 111:103707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103707

Raphael DB, Russell NS, Immink JM et al (2020) Risk communication in a patient decision aid for radiotherapy in breast cancer: how to deal with uncertainty? Breast 51:105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.04.001

Wang Y, Feng W (2022) Cancer-related psychosocial challenges. Gen Psychiatr 35:e100871. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2022-100871

Niedzwiedz CL, Knifton L, Robb KA et al (2019) Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: a growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer 19:943. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4

Emery J, Butow P, Lai-Kwon J et al (2022) Cancer survivorship 1 management of common clinical problems experienced by survivors of cancer. Lancet 399:1537–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00242-2

Park S, Sato Y, Takita Y et al (2020) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological distress, fear of cancer recurrence, fatigue, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in patients with breast cancer—a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 60:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.02.017

Wang Y, Liao L, Lin X et al (2021) A bibliometric and visualization analysis of mindfulness and meditation research from 1900 to 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:13150. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413150

Wang M, Yi G, Gao H et al (2020) Music-based interventions to improve fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis. Explore 16:357–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2020.05.012

Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE et al (2017) Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017:CD004517. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004517.pub3

Geyik Gİ, Doğan S, Ozbek H, Atayoglu AT (2021) The Effect of Music Therapy on the Physical and Mental Parameters of Cancer Patients During Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Perspect Psychiatr Care 57:558–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12578

Tang H, Chen L, Wang Y et al (2021) The efficacy of music therapy to relieve pain, anxiety, and promote sleep quality, in patients with small cell lung cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 29:7299–7306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06152-6

Santos MS dos, Thomaz F de M, Jomar RT et al (2021) Music in the relief of stress and distress in cancer patients. Rev Bras Enferm 74:e20190838. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0838

Gramaglia C, Gambaro E, Vecchi C et al (2019) Outcomes of music therapy interventions in cancer patients—a review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 138:241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.04.004

Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L (2013) Music-based interventions in palliative cancer care: a review of quantitative studies and neurobiological literature. Support Care Cancer 21:2609–2624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1841-4

Pearson S (2018) Why words matter: how the common mis-use of the term music therapy may both hinder and help music therapists. Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy 18. https://doi.org/10.15845/voices.v18i1.904

Dileo C, Bradt J (2009) Medical music therapy: evidence-based principles and practices. Int Handbook Occup Ther Interv 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-75424-6_47/COVER

Pereira APS, Marinho V, Gupta D et al (2019) Music therapy and dance as gait rehabilitation in patients with parkinson disease: a review of evidence. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 32:49–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988718819858

Zhou Z, Zhou R, Wei W et al (2021) Effects of music-based movement therapy on motor function, balance, gait, mental health, and quality of life for patients with parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 35:937–951. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215521990526

Torres E, Pedersen IN, Pérez-Fernández JI (2018) Randomized trial of a group music and imagery method (GrpMI) for women with fibromyalgia. J Music Ther 55:186–220. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thy005

Liao J, Wu Y, Zhao Y et al (2018) Progressive muscle relaxation combined with chinese medicine five-element music on depression for cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Chin J Integr Med 24:343–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11655-017-2956-0

Stanczyk MM (2011) Music therapy in supportive cancer care. Rep Practic Oncol Radiotherap 16:170–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpor.2011.04.005

Koshimori Y, Thaut MH (2019) New perspectives on music in rehabilitation of executive and attention functions. Front Neurosci 1313:1245. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNINS.2019.01245/FULL

Thaut MH, Francisco G, Hoemberg V (2021) Editorial: the clinical neuroscience of music: evidence based approaches and neurologic music therapy. Front Neurosci 15:740329 https://doi.org/10.3389/FNINS.2021.740329/FULL

Stegemöller EL (2014) Exploring a neuroplasticity model of music therapy. J Music Ther 51:211–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thu023

Sachs ME, Ellis RJ, Schlaug G, Loui P (2016) Brain connectivity reflects human aesthetic responses to music. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 11(6):884–891. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsw009

Finn S, Fancourt D (2018) The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: a systematic review. Prog Brain Res 237:173–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.007

Juslin P, Barradas G, American TE (2015) From sound to significance: exploring the mechanisms underlying emotional reactions to music. Am J Psychol 128(3):281–304. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.128.3.0281

Köhler F, Martin ZS, Hertrampf RS et al (2020) Music therapy in the psychosocial treatment of adult cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 11:651. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00651

Li Y, Xing X, Shi X et al (2020) The effectiveness of music therapy for patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 76:1111–1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14313

Bao Y, Kong X, Yang L et al (2014) Complementary and alternative medicine for cancer pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Evid-Based Complement Alternat Med 2014:170396. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/170396

Ioannidis J (2017) Next-generation systematic reviews: prospective meta-analysis, individual-level data, networks and umbrella reviews. Br J Sports Med 51:1456–1458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097621

Nascimento DP, Gonzalez GZ, Araujo AC et al (2019) Eight in every 10 abstracts of low back pain systematic reviews presented spin and inconsistencies with the full text: an analysis of 66 systematic reviews. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 50:17–23. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2020.8962

Beller EM, Glasziou PP, Altman DG et al (2013) Prisma for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med 10:e1001419. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001419

Gates M, Gates A, Pieper D et al (2022) Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the prior statement. BMJ 378:e070849. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ-2022-070849

Krnic Martinic M, Pieper D, Glatt A, Puljak L (2019) Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks. BMC Med Res Methodol 19:203. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0855-0

Tsai HF, Chen YR, Chung MH et al (2014) Effectiveness of music intervention in ameliorating cancer patients’ anxiety, depression, pain, and fatigue: a meta-analysis. Cancer Nurs 37:E35–E50. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000116

Wang X, Zhang Y, Fan Y et al (2018) Effects of music intervention on the physical and mental status of patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Care 13:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487073

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G et al (2017) AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Ciapponi A (2018) AMSTAR-2: Herramienta de evaluación crítica de revisiones sistemáticas de estudios de intervenciones de salud. Evidencia, actualizacion en la práctica ambulatoria 21. https://doi.org/10.51987/evidencia.v21i1.6834

Yavchitz A, Ravaud P, Altman DG et al (2016) A new classification of spin in systematic reviews and meta-analyses was developed and ranked according to the severity. J Clin Epidemiol 75:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.020

Pérez-Bracchiglione J, Meza N, Bangdiwala SI et al (2022) Graphical representation of overlap for overviews: groove tool. Res Synth Methods 13:381–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/JRSM.1557

Pieper D, Antoine SL, Mathes T et al (2014) Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J Clin Epidemiol 67:368–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.007

Garza-Villarreal EA, Pando V, Vuust P, Parsons C (2017) Music-induced analgesia in chronic pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician 20:597–610. https://doi.org/10.1101/105148

Nightingale CL, Rodriguez C, Carnaby G (2013) The impact of music interventions on anxiety for adult cancer patients: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Integr Cancer Ther 12:393–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735413485817

Park YJ, Lee MK (2021) Effects of nurse-led nonpharmacological pain interventions for patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nurs Scholar. https://doi.org/10.1111/JNU.12750

Bro ML, Jespersen KV, Hansen JB et al (2018) Kind of blue: a systematic review and meta-analysis of music interventions in cancer treatment. Psychooncology 27:386–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/PON.4470

Qi Y, Lin L, Dong B et al (2021) Music interventions can alleviate cancer-related fatigue: a metaanalysis. Support Care Cancer 29:3461–3470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-05986-4

Yang T, Wang S, Wang R et al (2021) Effectiveness of five-element music therapy in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract 44:101416. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CTCP.2021.101416

Yangöz ŞT, Özer Z (2019) The effect of music intervention on patients with cancer-related pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs 75:3362–3373. https://doi.org/10.1111/JAN.14184

Tao W-W, Jiang H, Tao X-M et al (2016) Effects of acupuncture, tuina, tai chi, qigong, and traditional chinese medicine five-element music therapy on symptom management and quality of life for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 51:728–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.027

Sezgin MG, Bektas H (2022) The effect of music therapy interventions on fatigue in patients with hematological cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Support Care Cancer 30:8733–8744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07198-w

Nguyen KT, Xiao J, Chan DNS et al (2022) Effects of music intervention on anxiety, depression, and quality of life of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 30(7):5615–5626. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-022-06881-2

Bradt J, Dileo C, Myers-Coffman K, Biondo J (2021) Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8):CD006911. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006911.pub2

Kocot-Kępska M, Zajączkowska R, Zhao J et al (2021) The role of complementary and alternative methods in the treatment of pain in patients with cancer - current evidence and clinical practice: a narrative review. Wspolczesna Onkologia 25:88–94. https://doi.org/10.5114/wo.2021.105969

Lunde SJ, Vuust P, Garza-Villarreal EA, Vase L (2019) Music-induced analgesia: how does music relieve pain? Pain 160:989–993. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001452

Howlin C, Rooney B (2021) The cognitive mechanisms in music listening interventions for pain: a scoping review. J Music Ther 57:127–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thaa003

Lemaire A, George B, Maindet C et al (2019) Opening up disruptive ways of management in cancer pain: the concept of multimorphic pain. Support Care Cancer 27:3159–3170. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-019-04831-Z

Maindet C, Burnod A, Minello C et al (2019) Strategies of complementary and integrative therapies in cancer-related pain-attaining exhaustive cancer pain management. Support Care Cancer 27:3119–3132. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-019-04829-7

Greenlee H, DuPont-Reyes MJ, Balneaves LG et al (2017) Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin 67:194–232. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21397

Tan JY, Zhai J, Wang T et al (2022) Self-managed non-pharmacological interventions for breast cancer survivors: systematic quality appraisal and content analysis of clinical practice guidelines. Front Oncol 12:866284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.866284

Gustavson DE, Coleman PL, Iversen JR et al (2021) Mental health and music engagement: review, framework, and guidelines for future studies. Transl Psychiatry 11:370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01483-8

Coelho A, Parola V, Cardoso D et al (2017) Use of non-pharmacological interventions for comforting patients in palliative care: a scoping review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 15:1867–1904. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003204

Rodríguez-Rodríguez R-C, Noreña-Peña A, Chafer-Bixquert T et al (2022) The relevance of music therapy in paediatric and adolescent cancer patients: a scoping review. Glob Health Action 15:2116774. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2022.2116774

González-Martín-Moreno M, Garrido-Ardila EM, Jiménez-Palomares M et al (2021) Music-based interventions in paediatric and adolescents oncology patients: a systematic review. Children 8:73. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8020073

Sheikh-Wu SF, Kauffman MA, Anglade D et al (2021) Effectiveness of different music interventions on managing symptoms in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs 52:101968. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJON.2021.101968

Kiernan J, DeCamp K, Sender J, Give C (2022) Barriers to implementation of music listening interventions for cancer-related phenomena: a mapping review. J Integr Complement Med 10. https://doi.org/10.1089/jicm.2022.0623

Yamato T, Maher C, Saragiotto B et al (2016) The TIDieR checklist will benefit the physical therapy profession. Phys Ther 96:930–931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2016

Bradt J, Potvin N, Kesslick A et al (2015) The impact of music therapy versus music medicine on psychological outcomes and pain in cancer patients: a mixed methods study. Support Care Cancer 23:1261–1271. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-014-2478-7

Klastersky J, Libert I, Michel B et al (2016) Supportive/palliative care in cancer patients: quo vadis? Support Care Cancer 24:1883–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-015-2961-9

Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M et al (2013) Concepts and definitions for “supportive care”, “best supportive care”, “palliative care”, and hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 21:659–685. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00520-012-1564-Y

Flores H, Kannan D, Ottwell R et al (2021) Evaluation of spin in the abstracts of systematic reviews and meta-analyses on breast cancer treatment, screening, and quality of life outcomes: a cross-sectional study. J Cancer Policy 27:100268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcpo.2020.100268

Funding

Funding for open access publishing: Universidad de Sevilla/CBUA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ATM, AMHR; Methodology: ATM, JMC, MJCH, PGG, AMHR; Formal analysis and investigation: ATM, JMC, MJCH, PGG, AMHR; Writing-original draft preparation: ATM, JMC, MJCH, PGG, AMHR; Writing-review and editing: ATM, JMC, MJCH, PGG, AMHR; Supervision: ATM, AMHR.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Due to the design of this study, ethics approval was not required.

Conflicts of interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Registered protocol: Open Science Framework, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Y67BU.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Trigueros-Murillo, A., Martinez-Calderon, J., Casuso-Holgado, M.J. et al. Effects of music-based interventions on cancer-related pain, fatigue, and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. Support Care Cancer 31, 488 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07938-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-07938-6