Abstract

Purpose

To systematically review and examine current evidence for the carer-reported benefits of supportive care strategies for carers of adults with high-grade glioma (HGG).

Methods

Four databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed, PsycINFO) were searched for articles published between January 2005 and April 2022 that assessed strategies for addressing the supportive care needs of carers of adults with HGG (WHO grade 3–4). Study selection and critical appraisal were conducted independently by three authors (DJ/MC, 2021; DJ/RJ 2022). Data extraction was conducted by one author (DJ) and checked by a second author (RJ). Results were synthesised narratively.

Results

Twenty-one studies involving 1377 caregivers were included, targeting the carer directly (n = 10), the patient-carer dyad (n = 3), or focused on people with HGG + / − their carers (n = 8). A paucity of high-quality evidence exists for effective and comprehensive support directly addressing outcomes for carers of adults with HGG. Strategies that demonstrated some benefits included those that built carer knowledge or provided emotional support, delivered by health professionals or through peer support. Supportive and early palliative care programmes have potential to reduce unmet carer needs while providing ongoing carer support.

Conclusion

Strategies incorporating an educational component, emotional support, and a regular needs assessment with corresponding tailored support are most valued by carers. Future practice development research should adopt a value-based approach and exceed evaluation of efficacy outcomes to incorporate evaluation of the experience of patients, carers, and staff, as well as costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Primary brain cancer is a rare (3.5/100,000) [1] yet serious disease. High-grade glioma (HGG), defined as grade 3 and grade 4 glioma by the World Health Organisation (WHO) [2], is most common in adults and is often characterised by the rapid onset and progression of physical and neurological symptoms [3]. Even with standard-of-care treatment comprising surgery followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy, patients with glioblastoma (WHO grade 4 glioma) have a median overall survival of 12–23 months [4]. Most people with HGG are managed in the outpatient setting, therefore their spouse or other family members usually accept primary responsibility for care [5]. With little time to prepare, carers must learn to navigate the health care system and assume new roles including patient advocate, driver, and medication manager while simultaneously fulfilling pre-existing responsibilities within the family unit [6]. These role changes can lead to significant carer distress, anxiety, and depression [7], with distress continuing throughout the disease trajectory [8] and into bereavement [9].

Carers for people with HGG have unmet needs across a variety of domains, including the need for proactive information [10] and support to manage changing symptoms across the illness continuum [11]. Emotional support is essential as a ‘lifeline’ for carers struggling with grief [12] and the loneliness of caring [13], and acknowledging carer needs recognises and validates their essential role in the caregiving process [14]. To address carers’ unmet needs and improve the provision of supportive care services for people with HGG and their carers, it is essential to identify, synthesise, and evaluate strategies addressing these needs [15].

Several reviews have previously been conducted canvassing supportive care interventions for carers of people with HGG, with no reliable conclusions able to be drawn due to a lack of robust data and adequately-powered studies to evaluate their effectiveness. Sherwood and colleagues [16] undertook a narrative review of neuro-oncology family caregiving. Boele and colleagues [17] conducted a systematic Cochrane review identifying three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of supportive interventions for carers of adults with HGG [18,19,20]. Ownsworth and colleagues [21] explored the use of telehealth platforms to deliver supportive care and identified participation by HGG carers in four studies [22,23,24,25]. Lastly, a recent systematic review by Heinsch and colleagues [26] examined feasibility and effectiveness of interventions for friends/family of adults with benign and malignant primary brain tumours, with most studies being small-scale or pilot studies (≤ 60 participants). Therefore, conducting another systematic review purely focused on efficacy is likely unfruitful.

Given the rarity of HGG and the complexity of designing and conducting trials with this population [16, 27], it is particularly important to consider what supportive care strategies may be beneficial from the carers’ perspective. To identify supportive strategies valued by carers that address carer-identified needs, and to explore what components of supportive care are most promising to pursue in future research and practice development, this review sought to extend beyond efficacy outcomes and broaden our understanding of strategies helpful for yielding carer-reported benefits. Findings from this review will inform future research for carers of people with HGG, recognising their essential role as partners in the caregiving process.

Methods

This systematic review was reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) 2020 statement [28] and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021271208).

Search strategy

Four databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, PubMed, PsycINFO) were searched for studies published from 1 January 2005 to 11 August 2021 using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and key words. The systematic search strategy (Fig. 1) used the following: [(high-grade glioma OR glioblastoma OR primary malignant brain tumour OR primary brain tumour OR glioma) AND (carer OR caregiver OR informal carer OR family caregiver)]. Reference lists of included records were screened, and the search strategy repeated 30 April 2022 to update the findings.

Selection of studies

Two authors (DJ and RJ) independently conducted title, abstract, and full-text screening in duplicate, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Inclusion criteria included [1] adult (> 18 years) carers of adults with HGG, whereby carers were defined as the principal unpaid, informal caregiver; [2] any supportive strategy involving carer participation which reported quantitative and/or qualitative carer data, implemented at any stage of the disease trajectory; [3] described or evaluated any intervention, programme, or service that addressed any carer needs including psychological/emotional needs, information, health service needs, and work/social needs [29]; and [4] included studies of any design published in peer-reviewed journals and written in English. Studies of carers for people with glioma from mixed histologies were excluded if the authors identified < 50% HGG participants. Unpublished articles, theses, pre-prints, trial registries, published study protocols, conference abstracts, and case studies were excluded.

Review of study quality, data extraction, and synthesis

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomised Studies-of Interventions (ROBINS-I) assessment tool [30], Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias tool for randomised trials (RoB-2) [31], or Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [32]. Two authors (DJ/MC, 2021; DJ/RJ, 2022) independently critically appraised studies, with disagreements resolved via consensus. The primary outcome was any benefit to carers of people with HGG, with benefits assessed by any outcome measure (e.g. carer knowledge, supportive care activities, quality of life, satisfaction) using any tool. One author (DJ) extracted data relating to study characteristics, participants, strategies utilised, and findings, with data extraction for all studies verified by a second author (RJ). Disagreements regarding data extraction were managed by discussion between authors. Due to the high level of heterogeneity of interventions and types of benefits reported, a meta-analysis was not planned. Data on carer-reported benefits were narratively synthesised under categories of supportive strategies. The narrative synthesis process was consistent with guidance provided by Popay and colleagues [33].

Results

Search results and study quality

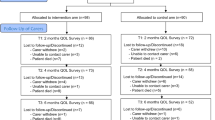

A total of 21 studies were evaluated (Fig. 1), including eight (38%) non-randomised studies, six (29%) randomised trials, four (19%) mixed-methods, two (10%) qualitative, and one (5%) quantitative descriptive study. All non-randomised studies were assessed to have a serious risk of bias in the selection of participants and reporting of results [34], or by failing to report, or adjust for, confounders [24, 35,36,37,38,39,40] (Table 1). Four of six randomised studies were assessed to have a high risk of bias, due to the randomisation process [19], deviation from intended intervention [19, 20, 41, 42], or missing outcome data [18,19,20, 41, 42].

Study characteristics

Twenty-one studies involving 1377 participants from six countries were included: USA (n = 10), Australia (n = 4), Denmark (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), and one study each in Canada, Netherlands and UK (Table 2). Three studies used a specialist cancer nurse [23, 24, 35] (n = 94 participants), or a neuro-oncology caregiver programme (1 study [38] (n = 90 participants). Other strategies included education workshops (2 studies [40, 43] (n = 51 participants), meaning-centred psychotherapy (1 study [44] (n = 9 participants), and cognitive behavioural therapy or problem-solving strategies (3 studies [18, 19, 41] (n = 195 participants). One pilot study assisted carers to identify their social support networks (2 papers [20, 42] (n = 40 participants). One study reviewed carer utilisation of a brain tumour website that provided information and on-line support [22] (n = 8 participants), and one study compared psychological support with different follow-up care pathways [45] (n = 32 participants). Other studies reported on carer participation in a residential rehabilitation programme (1 study [46] (n = 16 participants), and evaluated dyadic yoga, exercise, and couple-based meditation (4 studies [25, 36, 47, 48] (n = 75 participants). Finally, three studies addressed carer support in the palliative phase of disease [34, 37, 39] (n = 767 participants).

Benefits to carers were measured by the number and type of supportive activities undertaken during the study [22, 23, 35, 38], carer feedback [34, 43, 44, 46, 48], or by a change in physical or mental wellbeing [20, 25, 34, 36, 41, 45, 47], quality of life [19], caregiver strain [34], or burden [41], mastery [18, 41], knowledge [40, 43], preparedness to care [24], or satisfaction [37, 39, 46]. Significance was assumed if p < 0.05 (Table 2).

Participant characteristics

Most carers were female (50–100% of participants), with a mean age range of 50–60 years, and identified as the spouse or partner (range 50–92%). People with HGG were predominantly male in twenty studies (50–72% of participants), with a mean age range of 46–64 years, and included those with a recent diagnosis through to a terminal phase of disease. Several studies did not report carer demographics [19, 22], demographics of people with HGG [43, 44], or demographics for either group [37,38,39].

Supportive strategies: information/education/problem-solving

Carers reported benefit across several domains by attending education workshops. Knowledge scores improved after attending a neuro-oncology workshop focused on carer-identified topics including disease and treatment options, symptom management, and strategies to manage cognitive changes (n = 24) [43]. Carers positively evaluated the programme meeting their needs regarding content, location, and timing, although 25% would have liked the information earlier in the care trajectory [43]. Sharing experiences with other carers was highlighted as beneficial by 71% of participants, while others valued talking informally with healthcare staff and being acknowledged as the primary carer [43]. Similarly, an education session on tumour-related epilepsy demonstrated an increase in carer knowledge, although the need for information earlier was again reported (n = 27) [40]. Carers highlighted that the intervention reduced their worry, and increased their confidence and preparedness to manage seizures [40].

Conversely, 63% of carers did not access a brain tumour website providing tailored information and on-line support (n = 8) [22]. One ‘non-user’ acknowledged the value of the service, and two carers utilised the ‘ask the specialist’ service; however, other feedback suggested a lack of confidence in internet information meeting their individual needs, and a perception that web-based interventions were better suited to younger people.

A recent three-arm RCT of a problem-solving intervention (+ / − cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depression) demonstrated a significant reduction in caregiving-specific distress compared to ‘enhanced care as usual’ (n = 120) [41]. ‘Smart Care’ involved an online needs-based assessment and goal-setting strategy with nurse support. The intervention arms were combined due to poor CBT accrual; however, only 58% of carers initiated a needs assessment and plan, with higher attrition in the intervention group (36%) compared to control (13%). While carers noted the intervention to be helpful, feedback also highlighted the importance of carer autonomy in choosing when to engage in a supportive strategy [41]. In comparison, a dyadic cognitive rehabilitation and problem-solving RCT (n = 19 dyads) [19] was also evaluated by carers as ‘helpful’; however, it demonstrated no significant improvement in carer quality of life or mood status compared to usual care [19].

Supportive strategies: peer/psychological/social support

The value of peer support was highlighted by carers (n = 16) participating as dyads in a residential rehabilitation programme [46]. Carers valued having a ‘safe space’ to discuss issues without the patient being present, and support from other carers in sharing personal experiences of challenging situations [46]. Similarly, the opportunity to reflect on, and find meaning in the caregiving experience was reported as beneficial by carers participating in a psychotherapy study (n = 9) [44]. In contrast, the evaluation of follow-up care pathways for people with HGG (n = 40) and carers (n = 32) concluded that neither pathway had an impact on carer psychological wellbeing [45]. While carers reported satisfaction with both pathways, the need for emotional support was identified as the primary recommendation for service improvement.

A significant increase in mastery was reported from a RCT involving CBT and psychoeducation (n = 56) [18]. Carers highlighted needing support to manage patient-related concerns, deal with family/friends, and find time for themselves. However, there was higher attrition in the intervention group (52%) compared to controls (32%), suggesting that study participation was likely too burdensome for participants.

The impact of complementary therapies on mental wellbeing was explored in several studies. Milbury and colleagues [36] conducted a pilot of dyadic yoga (n = 5 dyads), followed by a pilot RCT (n = 20 dyads) [47]. Participants reported the intervention ‘useful’ and ‘beneficial’, with significantly less carer depressive symptoms compared to waitlist control [47]. Similarly, carers participating as dyads in a tailored exercise programme (n = 15) noted the value of mutual motivation, and focusing on something ‘other than the cancer’ [48]. The opportunity to ‘take time out’ while the person with HGG was in a safe and supportive programme was also valued, although challenges in coordinating appointments were noted [48]. Carer feedback from a pilot RCT of couple-based meditation (n = 35 couples) rated the components ‘beneficial’, the programme ‘useful’, and would recommend it to other couples [25]. Participants valued the dyadic format; however, there were no significant group differences in carer depressive symptoms, mindfulness, compassion, or intimacy compared to usual care.

‘Eco-mapping’ social support networks was evaluated in a randomised pilot study for 40 carers using an electronic Social Network Assessment Program (eSNAP) [20, 42]. Carers reported the phone application was easy to understand and helped them consider their support networks. However, only 20% referred back to the ‘eco-map’ at subsequent reviews, and there was no significant intervention effect on carer anxiety, burden, or helpfulness of support compared to usual care.

Supportive strategies: comprehensive support: specialist nurse-led programmes

The ‘Care-IS’ pilot programme included a needs assessment, nurse-led home visit, tailored resource manual, and monthly phone support (n = 10) (23). Carers reported the manual’s information was helpful and understandable; however, feedback also identified the need for additional information which was added to the resource manual. Although carers were recruited within two months of diagnosis, 40% would have preferred the information earlier in the disease trajectory. There were 79 documented episodes of information provision/referrals, with carers needing support to manage symptoms, mental and behavioural changes, financial concerns, and anxiety and distress.

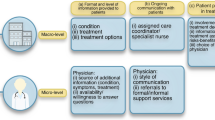

Philip and colleagues [24] reported on the non-randomised ‘I-CoPE’ study where cancer care coordinators provided staged information, regular needs screening, and emotional support for people with HGG (n = 32) and their carers (n = 31). The intervention targeted three transition points: after diagnosis, following hospital discharge, and after completion of radiotherapy. Results demonstrated a significant reduction in unmet information and supportive care needs, and increased preparedness to care [24]. Carer distress declined over time, though remained at clinically relevant levels throughout the intervention [49]. Most carers (87%) rated overall care to be ‘excellent’, including ‘high’ satisfaction with communication and ‘very high’ confidence and trust in the care team [24]. Carer-reported needs changed from an early focus on practical concerns regarding treatment and care responsibilities, to later needs focused on managing the emotional impact on children and family coping.

‘FamilyStrong’ offered a programme of nurse-led telehealth support for 53 carers of people with newly-diagnosed HGG [35]. Providing emotional support and education were the most frequent activities from the 211 documented encounters, with 59% of carers reporting moderate or high distress. Carers distinguished between problems that ‘bothered them the most’, as distinct from issues they wanted ‘assistance to manage’ which included managing their relative’s health condition/symptoms, coordinating care/services, sadness, and planning for the future.

Supportive strategies: comprehensive support: clinic-based caregiver programme

The Neuro-Oncology Gordon Murray Caregiver Program at the University of California, San Francisco, provided regular phone reviews, peer support, support groups, and an annual neuro-caregiver workshop [38]. Carer-reported benefits included increased knowledge and emotional support from sharing concerns and discussing coping strategies. Feedback also highlighted the value of repeated screening and outreach calls to improve satisfaction with care, and identify carer readiness to accept help. Supportive care needs changed over time and included the need for emotional support, advocacy assistance, and support to address family coping.

Supportive strategies: comprehensive support: palliative phase

Aoun and colleagues [34] analysed a sub-set of HGG carers (n = 29) from a community-based palliative care trial [50]. Results from the wider trial demonstrated a significant reduction in caregiver strain compared to controls [50], with no significant effect for HGG carers. Carer needs changed over time, with ‘knowing what to expect in the future’ remaining the highest reported need, and ‘managing your relative’s symptoms’ increasing from baseline. Qualitative feedback highlighted that regular needs screening provided reassurance, helped empower carers to find solutions and encouraged them to reflect on the emotional impact of caregiving. While this intervention targeted the end-of-life home-based phase of care, carers noted it would have been beneficial earlier in the disease trajectory [34].

A programme of early comprehensive palliative home care [37] was also positively valued by carers (n = 616), with high satisfaction rates across all support domains including home-care assistance (98%), nursing (95%), communication (93%), rehabilitation at home (92%) and social work help (88%). Hospital re-admission rates were lower in the last two months of life compared to a similar cohort of glioblastoma patients (16.7% vs 38%), which helped maintain carer support into bereavement. A later cohort of participants in this programme (n = 122) also reported high satisfaction rates across all domains [39] and identified that education, including learning physical care strategies, allowed carers to be more involved in the care of their loved one and increased carer satisfaction.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesises current evidence of carer-reported benefits from strategies to address supportive needs of carers for people with HGG. As expected, we found limited evidence of the efficacy of supportive strategies. Instead of focusing on efficacy alone, this review took a slightly different approach to identify and synthesise carer-reported benefits. This approach is more likely to allow clinicians and researchers to incorporate strategies valued by carers as the evidence base in this area continues to evolve. Overall, strategies that provided peer support [43, 46] and emotional support from health professionals [34, 38, 43] appeared to be highly valued by carers. Supportive and early palliative care strategies appeared to reduce carers’ unmet needs, increase preparedness to care, and provide support for the whole family [24, 37, 39]. Educational strategies such as workshops [19, 42] and individualised resources [23] also demonstrated some carer-reported benefits and are potential strategies for building carer knowledge and skills to manage symptoms.

It is noteworthy that several studies failed to report meaningful qualitative data to build our understanding of carer benefit [35]. For example, carers evaluated programmes to be ‘helpful’ and ‘useful’ [19, 20, 25] without any further qualitative exploration of benefit, or demonstrating intervention efficacy. It is uncertain whether this discrepancy could be due to positive response bias, a placebo effect of participating in any supportive strategy [20], or whether carers derived an added benefit from the intervention beyond the pre-determined outcome measures (e.g. peer support from other participants) [43]. Prioritising qualitative data collection using a mixed-methods approach, including carer perception of benefit, alongside the assessment of quantitative outcomes is congruent with the recommendations of Heinsch and colleagues [26] for future research to reflect the caregiver experience of participating in supportive care strategies.

Supportive strategies valued by carers were those that incorporated some element of emotional support [34, 38]. Peer support was perceived as valuable in providing a ‘safe space’ for carers to discuss sensitive issues and share experiences [43, 46]. Emotional support from health professionals helped to validate the carer’s role and reduce isolation [34, 43]. ‘Flagging’ issues with the nurse, even in the absence of a ready solution, was also reported to be beneficial [34]. While most strategies built rapport with face-to-face interactions [24], telehealth services offered the advantage of ongoing support at a time convenient for the clinician and carer [35].

Strategies that provided carer education were valued by carers to improve knowledge, confidence, and preparedness to care [40, 43]; however, carer feedback identified the need for knowledge earlier in the illness continuum [23, 34, 40, 43, 46]. Previous research has highlighted that timing of information provision is crucial, with too much information potentially overwhelming the carer, and too little leaving them unprepared [6, 51, 52]. This finding was echoed in the ‘Care-IS’ study, with some carers wanting comprehensive information immediately after diagnosis, whereas others recognised they would be unable to process it [23]. While timing and delivery of information can vary depending on individual carer preferences, it remains that timely education and upskilling of carers is a proactive measure that can help build carer competence and confidence [10, 13, 38, 40].

In the included studies, the principal areas of carer-reported need focused on knowledge and symptom management [23, 24, 34, 35, 38,39,40, 43] alongside emotional support [23, 24, 34, 35, 38, 45, 46], with added concerns regarding the impact of a HGG diagnosis on children and family coping [18, 24, 37, 38]. Other carer-identified needs included understanding mental and behavioural changes [23, 43], coordinating services [23, 35, 38], and planning for the future [23, 34, 35]. Financial concerns, including insurance, employment, and disability entitlements [23, 38], were also reported, with one strategy recording health care utilisation data and out-of-pocket costs to determine health economics cost-consequences [23]. These carer-identified needs changed across the illness continuum, reflecting the dynamic trajectory of caregiving for people with HGG.

While individual strategies may be of benefit in addressing one facet of need [47], the diversity of carer-identified needs outlined above highlights the importance of supportive interventions that can respond to emerging needs across the illness continuum [34, 38]. As such, supportive strategies should be based on regular, carer-driven needs assessment to identify in what domains the carer wants support. A recent study by Pointon and colleagues [53] reaffirmed this distinction between unmet needs and those that carers wanted support to address. Encouraging carers to identify when and where they require assistance not only provides an individualised response [35], but avoids unwanted and unnecessary interventions that could strain already limited health care resources [54]. These findings support the value-based approach in formulating and providing support to carers of people with HGG.

Translating beneficial trial strategies into clinical practice requires consideration of financial and resource allocation factors, and the capacity of health services to support implementation in the clinical setting. For example, a residential rehabilitation programme invested significant time and resources to benefit a small cohort of participants [46]. This finding is congruent with a systematic review of oncology carer interventions with only 11% of interventions less than 3 h in duration, potentially limiting their integration into clinical practice [55]. Conversely, a crude cost analysis of ‘I-CoPE’ estimated a mean cost of AUD$137 per dyad, with the strategy able to be incorporated into existing care-coordinator models of care [24]. Similarly, the ‘Family Strong’ programme was time-efficient and could be integrated into social work or care coordinator roles [35]. Future trial-based economic evaluations and more pragmatic preference-based approaches such as discrete choice experiments may be helpful in informing future practice and policy decisions to allocate resources.

Limitations and ongoing or future research

There are several limitations in this review. The results of the published studies need to be interpreted with caution due to high risk of bias from missing data, measurement of outcomes, failure to adjust for confounders, or bias in the randomisation process. However, these limitations were expected, and therefore, this review focused on identifying carer-reported benefit to inform future research strategies. Grey literature was not included in this review and as such certain evaluations relevant to the topic of interest may not have been included. This review was also limited to studies published in English and conducted in Western countries which could limit generalisability of findings for carers in developing countries or from culturally diverse communities. Future research should also seek to include carers with a more diverse demographic, for example to explore the experiences of male partners, or children caring for parents with HGG.

There are several ongoing clinical trials which could provide further data to expand our knowledge of effective strategies for addressing supportive care needs. A ‘Care-IS’ RCT is currently in progress [56], as is a wait-list controlled trial combining eSNAP with a regular supportive phone review [57]. Similarly, further data are anticipated to expand on preliminary findings from recently published studies [41, 44]. Results from these RCTs and future research may contribute to identifying effective, efficient, and sustainable strategies to support carers of people with HGG.

Conclusion

This systematic review evaluated supportive care strategies aimed at carers of people with HGG to determine the benefit to carers from their participation. Carers reported benefit from a range of strategies that provided educational and emotional support. Carer needs are diverse and change across the illness continuum, therefore supportive services should be tailored to individual needs and include both informational, practical, and emotional support. Supportive strategies also need to be feasible in relation to time and resource allocation, and economically sustainable to facilitate successful implementation into healthcare settings. Additional research is needed to adopt a value-based approach and strengthen the body of evidence on how to best support carers of people with HGG.

References

Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M et al (2019) Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 144(8):1941–1953

Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D et al (2021) The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23(8):1231–1251

Madsen K, Poulsen HS (2011) Needs for everyday life support for brain tumour patients’ relatives: systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care 20(1):33–43

Berger TR, Wen PY, Lang-Orsini M, Chukwueke UN (2022) World Health Organization 2021 classification of central nervous system tumors and implications for therapy for adult-type gliomas: a review. JAMA Oncol

Piil K, Jakobsen J, Christensen KB, Juhler M, Guetterman TC, Fetters MD et al (2018) Needs and preferences among patients with high-grade glioma and their caregivers—a longitudinal mixed methods study. Eur J Cancer Care 27(2):1–13

McConigley R, Halkett G, Lobb E, Nowak A (2010) Caring for someone with high-grade glioma: a time of rapid change for caregivers. Palliat Med 24(5):473–479

Long A, Halkett GKB, Lobb EA, Shaw T, Hovey E, Nowak AK (2016) Carers of patients with high-grade glioma report high levels of distress, unmet needs, and psychological morbidity during patient chemoradiotherapy. Neuro-Oncol Practice 3(2):105–112

Halkett G, Lobb E, Shaw T, Sinclair M, Miller L, Hovey E et al (2017) Distress and psychological morbidity do not reduce over time in carers of patients with high-grade glioma. Support Care Cancer 25(3):887–893

Piil K, Nordentoft S, Larsen A, Jarden M (2019) Bereaved caregivers of patients with high-grade glioma: A systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 9(1):26–33

Collins A, Lethborg C, Brand C, Gold M, Moore G, Sundararajan V et al (2014) The challenges and suffering of caring for people with primary malignant glioma: qualitative perspectives on improving current supportive and palliative care practices. BMJ Support Palliat Care 4(1):68–76

Halkett GKB, Lobb EA, Shaw T, Sinclair MM, Miller L, Hovey E et al (2018) Do carer’s levels of unmet needs change over time when caring for patients diagnosed with high-grade glioma and how are these needs correlated with distress? Support Care Cancer 26(1):275–286

Francis SR, Hall EOC, Delmar C (2020) Ethical dilemmas experienced by spouses of a partner with brain tumour. Nurs Ethics 27(2):587–597

Coolbrandt A, Sterckx W, Clement P, Borgenon S, Decruyenaere M, De Vleeschouwer S et al (2015) Family Caregivers of patients with a high-grade glioma: a qualitative study of their lived experience and needs related to professional care. Cancer Nurs 38(5):406–413

Whisenant M (2011) Informal caregiving in patients with brain tumors. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(5):E373–E381

Boele FW, Grant R, Sherwood P (2017) Challenges and support for family caregivers of glioma patients. Br J Neurosci Nurs 13(1):8–16

Sherwood PR, Cwiklik M, Donovan HS (2016) Neuro-oncology family caregiving: review and directions for future research. CNS Oncol 5(1):41–48

Boele FW, Rooney AG, Bulbeck H, Sherwood P (2019) Interventions to help support caregivers of people with a brain or spinal cord tumour. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019(7)

Boele FW, Hoeben W, Hilverda K, Lenting J, Calis AL, Sizoo EM et al (2013) Enhancing quality of life and mastery of informal caregivers of high-grade glioma patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Neurooncol 111(3):303–311

Locke DEC, Cerhan JH, Wu W, Malec JF, Clark MM, Rummans TA et al (2008) Cognitive rehabilitation and problem-solving to improve quality of life of patients with primary brain tumors: a pilot study. J Support Oncol 6(8):383

Reblin M, Ketcher D, Forsyth P, Mendivil E, Kane L, Pok J et al (2018) Outcomes of an electronic social network intervention with neuro-oncology patient family caregivers. J Neurooncol 139(3):643–649

Ownsworth T, Chan RJ, Jones S, Robertson J, Pinkham MB (2021) Use of telehealth platforms for delivering supportive care to adults with primary brain tumors and their family caregivers: a systematic review. Psychooncol 30(1):16–26

Piil K, Jakobsen J, Juhler M, Jarden M (2015) The feasibility of a brain tumour website. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(6):686–693

Halkett GKB, Lobb EA, Miller L, Shaw T, Moorin R, Long A et al (2018) Feasibility testing and refinement of a supportive educational intervention for carers of patients with high-grade glioma - a pilot study. J Cancer Educ: the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education 33(5):967–975

Philip J, Collins A, Staker J, Murphy M (2019) I-CoPE: a pilot study of structured supportive care delivery to people with newly diagnosied high-grade glioma and their carers. Neuro-Oncol Practice 6(1):61–70

Milbury K, Weathers S-P, Durrani S, Li Y, Whisenant M, Li J et al (2020) Online Couple-based meditation intervention for patients with primary or metastatic brain tumors and their partners: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 59(6):1260–1267

Heinsch M, Cootes H, Wells H, Tickner C, Wilson J, Sultani G, et al (2021) Supporting friends and family of adults with a primary brain tumour: a systematic review. Health Soc Care Community

Catt S, Chalmers A, Fallowfield L (2008) Psychosocial and supportive-care needs in high-grade glioma. Lancet Oncol 9(9):884–891

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg 88:105906

Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C (2011) The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncol 20(4):387–393

Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT (2016) ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ 355

Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng H-Y, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT (2019) RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 366

Hong QN, F‡bregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman FK, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al (2018) The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf 34:285-91

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme2006.

Aoun SM, Deas K, Howting D, Lee G (2015) Exploring the support needs of family caregivers of patients with brain cancer using the CSNAT: a comparative study with other cancer groups. PLoS One 10(12)

Dionne-Odom JN, Williams GR, Warren PP, Tims S, Huang C-HS, Taylor RA et al (2021) Implementing a clinic-based telehealth support service (FamilyStrong) for family caregivers of individuals with grade IV brain tumors. J Palliative Med 24(3):347–53

Milbury K, Mallaiah S, Mahajan A, Armstrong T, Weathers S-P, Moss KE et al (2018) Yoga program for high-grade glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Integr Cancer Ther 17(2):332–336

Pace A, Villani V, Di Pasquale A, Benincasa D, Guariglia L, Ieraci S et al (2014) Home care for brain tumor patients. Neurooncol Pract 1(1):8–12

Page MS, Chang SM (2017) Creating a caregiver program in neuro-oncology. Neuro-Oncol Practice 4(2):116–122

Pompili A, Telera S, Villani V, Pace A (2014) Home palliative care and end of life issues in glioblastoma multiforme: results and comments from a homogeneous cohort of patients. Neurosurg Focus FOC 37(6 E5):1–4

Wasilewski A, Serventi J, Ibegbu C, Wychowski T, Burke J, Mohile N (2020) Epilepsy education in gliomas: engaging patients and caregivers to improve care. Support Care Cancer 28(3):1405–1409

Boele FW, Weimer JM, Proudfoot J, Marsland AL, Armstrong TS, Given CW et al (2022) The effects of SmartCare(©) on neuro-oncology family caregivers’ distress: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 30(3):2059–2068

Reblin M, Ketcher D, Forsyth P, Mendivil E, Kane L, Pok J et al (2018) Feasibility of implementing an electronic social support and resource visualization tool for caregivers in a neuro-oncology clinic. Support Care Cancer 26(12):4199–4206

Cashman R, Bernstein LJ, Bilodeau D, Bovett G, Jackson B, Yousefi M et al (2007) Evaluation of an educational program for the caregivers of persons diagnosed with a malignant glioma. Canad Oncol Nurs J Revue Canad De Nurs Oncologique 17(1):6–15

Applebaum AJ, Roberts KE, Lynch K, Gebert R, Loschiavo M, Behrens M, et al (2022) A qualitative exploration of the feasibility and acceptability of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy for Cancer Caregivers. Palliative and Supportive Care 1–7

Catt S, Chalmers A, Critchley G, Fallowfield L (2012) Supportive follow-up in patients treated with radical intent for high-grade glioma. CNS Oncol 1(1):39–48

Nordentoft S, Dieperink KB, Johansson SD, Jarden M, Piil K (2021) Evaluation of a multimodal rehabilitative palliative care programme for patients with high‐grade glioma and their family caregivers. Scandinavian J Caring Sci

Milbury K, Li J, Weathers S-P, Mallaiah S, Armstrong T, Li Y et al (2019) Pilot randomized, controlled trial of a dyadic yoga program for glioma patients undergoing radiotherapy and their family caregivers. Neuro-Oncol Practice 6(4):311–320

Halkett GKB, Cormie P, McGough S, Zopf EM, Galvão DA, Newton RU et al (2021) Patients and carers’ perspectives of participating in a pilot tailored exercise program during chemoradiotherapy for high grade glioma: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 30(5):e13453

Philip J, Collins A, Panozzo S, Staker J, Murphy M (2020) Mapping the nature of distress raised by patients with high-grade glioma and their family caregivers: a descriptive longitudinal study. Neuro-Oncol Practice 7(1):103–110

Aoun SM, Grande G, Howting D, Deas K, Toye C, Troeung L et al (2015) The impact of the carer support needs assessment tool (CSNAT) in community palliative care using a stepped wedge cluster trial. PloS one 10(4):e0123012-e

Lobb E, Halkett G, Nowak A (2011) Patient and caregiver perceptions of communication of prognosis in high grade glioma. Psychooncol 20:113

Arber A, Hutson N, Guerrero D, Wilson S, Lucas C, Faithfull S (2010) Carers of patients with a primary malignant brain tumour: are their information needs being met? Br J Neurosci Nurs 6(7):329–334

Pointon L, Grant R, Peoples S, Erridge S, Sherwood P, Klein M, Boele F (2021) P1206 Unmet needs and wish for support of informal caregivers of primary brain tumour patients. Neuro-Oncol 23:ii31–ii2

Applebaum AJ, Kent EE, Lichtenthal WG (2021) Documentation of caregivers as a standard of care. J Clin Oncol 39(18):1955–1958

Ferrell B, Wittenberg E (2017) A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology: family caregiving in oncology. CA: Cancer J Clin 67(4):318–25

Halkett GKB, Lobb EA, Miller L, Phillips JL, Shaw T, Moorin R et al (2015) Protocol for the Care-IS Trial: a randomised controlled trial of a supportive educational intervention for carers of patients with high-grade glioma (HGG). BMJ Open 5(10):e009477

Reblin M, Ketcher D, McCormick R, Barrios-Monroy V, Sutton SK, Zebrack B et al (2021) A randomized wait-list controlled trial of a social support intervention for caregivers of patients with primary malignant brain tumor. BMC Health Serv Res 21(1):1–8

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. RC received salary support from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1194051).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DJ, MP, and RC contributed to the study conception, study design, and acquisition of data.

DJ and RC designed the search term.

DJ, MC, and RJ performed the systematic search, article screening, data extraction, and data analysis.

DJ, MC, and RC prepared the first draft of the manuscript.

All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, D., Pinkham, M.B., Wallen, M.P. et al. Benefits of supportive strategies for carers of people with high-grade glioma: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 30, 10359–10378 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07419-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07419-2