Abstract

Climate change has affected the breeding parameters of many animal species. In birds, most studies have focused on the effects of temperature on clutch phenology and clutch size. The long-term influence of other weather factors, including rainfall, on breeding parameters have been analysed much less often. Based on a 23-year dataset and 308 broods, we documented shifts in the timing of breeding, clutch size and mean egg volume in a long-distance migrant, the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio, from a central European population. We found a 5-day shift towards delayed breeding, but no differences in brood size or egg volume during those 23 years. The GLM analysis showed that the mean May temperature had a positive influence on the clutch initiation date, whereas the number of days with rain delayed laying. During the period 1999–2021, there was no change in the mean May temperature, but total precipitation and the number of days with rain in May increased. Thus, delayed nesting in this population was probably due to the increase in rainfall during this period. Our results provide a rare example of delayed nesting in birds in recent years. Predicted changes in the climate make it difficult to assess the long-term impact of global warming on the viability of Red-backed Shrike populations in east-central Poland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

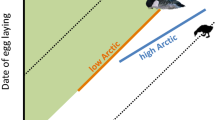

In recent decades, the Earth's climate has undergone changes, manifested mainly by increases in ambient temperatures, changes in rainfall patterns and the occurrence of extreme weather events (Houghton 2015). Such climate changes are having serious consequences for various species of plants and animals (Bellard et al. 2012; Gray and Brady 2016; Radchuk et al. 2019). The earlier arrivals of many migratory birds in their breeding areas and earlier laying dates during the last 20-30 years have been described over vast geographical areas (Tryjanowski et al. 2002; Both et al. 2004; Shipley et al. 2020). Changes in the breeding phenology in birds and the subsequent effects on their broods, especially among insectivorous species, are the consequence of altered access to food resulting from climate changes (Both et al. 2004; Charmantier et al. 2008). Most analyses have implicitly or explicitly assumed that temperature is the major driver of changes in breeding phenology and brood parameters in birds (Charmantier et al. 2008; Møller et al. 2010). Other studies have shown that higher temperatures favour earlier nesting, with the shift to earlier first-egg laying dates in some cases being more than 5 days in 10 years (Dunn and Winkler 1999; Halupka et al. 2020). Generally, early breeders tend to have larger clutches (Lack 1968; Dunn and Møller 2014) and are more likely to double brood (Bulluck et al. 2013; Townsend et al. 2013), but this is not always the case, probably because of the mismatch with the period of food abundance (Laaksonen et al. 2006; McDermott and Degroote 2016; Halupka et al. 2020). Some published data also show that the eggs of the species analysed became progressively smaller as a result of the mismatch between the dates food abundance and optimal egg formation by the female (Tryjanowski et al. 2004; Potti 2008). Because egg size affects juvenile survival, it is a very important breeding factor (Krist 2011).

The long-term effects of other weather factors on breeding parameters have been analysed far less often, one of these being rainfall (e.g. Laaksonen et al. 2006; Drake and Martin 2020). Climate change is manifested, for instance, by shifts in the intensity and duration of rainfall (Dore 2005). This appears to be of considerable significance for species inhabiting arid regions (Schneider and Griesser 2009; Cavalcanti et al. 2016) and tropical regions with a dry season (Brawn et al. 2017; Shaw 2017), as it stimulates plant growth and enhances food availability for birds at this time, thus improving female condition prior to egg laying (Oppel et al. 2014). On the other hand, the few published long-term data on breeding parameters in conjunction with rainfall from the temperate zone are not as convincing as in the case of air temperature. One such example demonstrated that local rainfall was an important negative driver of breeding phenology in Tree Swallows Tachycineta bicolor, although the productivity cost was minimal (Drake and Martin 2020). But in several other North American species, rainfall had no influence whatsoever on either clutch initiation dates or clutch sizes (Bowers et al. 2016; Drake and Martin 2018). Despite positive suggestions regarding the dominant part played by temperature in advancing nesting (Crick and Sparks 1999), some authors, e.g. Irons et al. (2017), state that it is actually rainfall that exerts a stronger influence on breeding phenology than temperature.

One of the most powerful approaches to inferring ecological effects of climate and climate change is to track phenological changes of local populations (Irons et al. 2017), and given the high annual variability of ecological studies, long-term research is key to discerning patterns and responses to global changes (Lindenmayer et al. 2012). The present study examines the breeding phenology and certain breeding parameters in Red-backed Shrikes Lanius collurio nesting in east-central Poland in the context of climate factors. This species was also the subject of similar studies involving temperature and rainfall in both the Czech Republic (Hušek and Adamík 2008) and western Poland (Tryjanowski 2002; Tryjanowski et al. 2004), but their results were inconclusive. The aim of the present study was to demonstrate the phenological trends relating to nesting, clutch size and mean egg volume in Red-backed Shrike broods during the last 23 years as affected by two basic climatic factors, i.e. air temperature and rainfall.

Material and methods

Study species

The Red-backed Shrike is a small passerine bird species widely distributed in Europe and western Asia, with population estimates ranging from 24 to 48 million breeding pairs, and because this species has a large population, it has been evaluated as being of Least Concern, although its numbers do appear to be decreasing (BirdLife International 2021). It is a long-distance migrant, which arrives at its breeding grounds from Africa in April/May (Harris and Franklin 2000). In eastern Poland, the majority of the population inhabits agricultural landscapes, breeding on the edge of woods, in clumps of trees, in orchards and near villages (Golawski and Meissner 2008). The breeding season usually starts in mid-May and extends into August. Three to seven eggs are laid and incubated for 14 days. The nestlings remain in the nest for the next 14 days, and fledglings stay around the nest for another two weeks or so (Harris and Franklin 2000). This species is normally single-brooded, but in case of first-brood failure, replacement clutches are laid regularly (Antczak et al. 2009). The Red-backed Shrike is a mainly insectivorous species (Tryjanowski et al. 2003; Golawski 2006).

Study site and data collection

The survey was carried out on ca 500 ha of the agricultural landscape around the town of Siedlce in eastern Poland (52.14° N, 21.93°E, Fig. 1), which has a temperate transitional climate (Degirmendzic et al. 2004). The study area abounded in meadows and pastures, subdivided by barbed wire fences, and there were scattered bushes and trees. Part of the research area was situated along a railway line with plenty of shrubs suitable as shrike nesting sites.

The study was carried out in the 1999-2003 and 2012–2021 breeding seasons, a period spanning 23 years. In each season, observations started in early May, when the first shrikes arrived, and ended in July/August, when the last pairs departed with their young. We searched for Red-backed Shrike nests, checking possible locations favourable for nesting and observing the birds’ behaviour, e.g. a male feeding the incubating female. We found between 10 and 59 (mean ± SD = 29.5 ± 15.3) nests each year. As most nests were found during egg laying or the early phase of incubation, calculating the clutch initiation date was straightforward; incubation advancement was based on the water test of the eggs (Wesołowski 1986). About 30% nests were found with nestlings. In these cases, the nestlings were weighed and their age estimated according to the age-body mass relationship, described for this species on the basis of data gathered in natural conditions (Diehl 1971). We assumed that Red-backed Shrikes lay one egg per day, begin incubating from the day when the penultimate egg is laid and continue to do so for 14 days (Harris and Franklin 2000). The detected nests were checked every 4–5 days to minimize the impact of the observer’s intrusion on nest survivorship (Tryjanowski and Kuzniak 1999; Golawski and Zduniak 2022). We measured eggs only in complete clutches (N = 142). The maximum length and breadth were measured with sliding callipers to the nearest 0.1 mm (all eggs measured by AG). We calculated the egg volume index (V) from the length (L) and breadth (B) using the formula re-scaled for the Red-backed Shrike: V = 0.5322 LB2 (Surmacki et al. 2006). The analysis does not include clutches in which brood advancement could not be accurately calculated.

Our records contain data relating to both first and replacement broods. As the inclusion of replacement broods is likely to influence the phenological statistics (Antczak et al. 2009), we defined first broods as those initiated before 10 June (for an identical approach, see Tryjanowski 2002). Our dataset thus consists of 308 broods out of the total of 442 recorded. On average, 40 pairs of shrikes nested in the study area each year (SD = 2.5, Range 36-44 pairs, n = 15 years), and the population showed no significant changes in numbers (Spearman rank correlation, R = -0.23, P = 0.418, n = 15).

Meteorological data

We used local weather data (Electronic supplementary material) to investigate the effect of climatic factors on the timing of breeding, clutch size and egg volume. Like Hušek and Adamík (2008) and Hušek et al. (2009), we used the weather data for the month of May, because it is during that month that Red-backed Shrikes arrive in east-central Poland and when most birds make their first breeding attempts (Antczak et al. 2009). The weather in May should thus affect laying dates and breeding parameters. We obtained the local weather data of interest to us, i.e. mean diurnal temperatures (in °C) in May, total precipitation (monthly sums in mm) and the number of days with rain in May, from http://www.tutiempo.net for the nearest meteorological station in Siedlce (a town 10 km south of the study area).

Statistical analysis

We used General Linear Models (GLM) with normal distribution and identity link functions to identify the factors affecting the Red-backed Shrike’s breeding parameters. We performed 3 analyses, where the dependent variables in the models were: 1) date of clutch initiation (when the first egg was laid), 2) clutch size, 3) mean volume of the eggs in a clutch. Mean values of all egg characteristics in the clutch were used as unit observations to avoid pseudoreplication (Lessells and Boag 1987). The explanatory variables used in all the models were weather factors in May: mean temperature, total precipitation and number of days with rain. Because population size could impact on nest detection – there is a higher probability of observing earlier clutch initiation when the population is larger (Tryjanowski and Sparks 2001; Hušek et al. 2009) – we used the number of nests in a year as a covariate. Another aspect to be taken into account is that the level of philopatry in the population studied is very low (Tryjanowski et al. 2007), so the probability that the same birds were included several times is rather low. The last explanatory variable used was the year of the study (1999-2002, 2012-2021). In all the GLMs, the interaction between temperature and the number of days with rain was introduced in the initial parameterization, but subsequently removed from the models because it was not significant in any of the analyses.

The explanatory variables were tested for multicollinearity by examining the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) (Quinn and Keough 2002). When VIF > 5, we discarded the variable from the analysis; one variable – total precipitation – was above the critical value, so we excluded it from the analysis. As not all breeding metrics were available for all broods, the sample sizes varied. Only those results with a probability of α ≤ 0.05 were assumed to be statistically significant. The analysis was performed in Statistica 12.0 (Statsoft 2014).

Results

Long-term changes in meteorological data

In east-central Poland during the study period (1999–2021), the May temperature showed no changes (linear regressions: F1,21 = 0.36, R2 = 0.02, P = 0.556; slope ± SE = -0.129 ± 0.216). However, total precipitation in May exhibited a positive trend (F1,21 = 4.35, R2 = 0.17, P = 0.049; slope ± SE = 0.414 ± 0.199) over the study period. Similarly, in the same period, the number of days with precipitation in May increased (F1,21 = 4.89, R2 = 0.19, P = 0.038; slope ± SE = 0.434 ± 0.199) (Electronic supplementary material).

Effects of weather on breeding parameters

The mean clutch initiation date in our Red-backed Shrikes was 31 May (SD = 6.6 days, range 6 May-10 June, n = 308 broods) and the date differed with respect to the factors analysed (GLM, F4,303 = 10.33, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.12, Table 1). In subsequent years, the shrikes initiated their clutches later and later (Fig. 2). Analysis of the trend showed that between 1999 and 2021 the shrikes nested 5.03 days later (2.2 days/10 years). The mean May temperature had a significant influence on the clutch initiation date; when temperatures were higher, the shrikes nested earlier (Fig. 3). In contrast, clutch initiation was delayed if there was a large number of days with rain in May (Fig. 4). The number of clutches in a given year did not affect the clutch initiation date (Table 1).

The mean clutch size was 5.5 eggs (SD = 0.7, Range 3-7, n = 235 clutches) and did not differ with respect to the factors analysed (GLM, F4,230 = 1.08, p = 0.369, R2 = 0.02, Table 1).

The mean egg volume in the clutches was 3.19 cm3 (SD = 0.25, Range 2.62-3.80, n = 142 clutches), and this, too, did not differ with respect to the factors analysed (GLM, F4,137 = 1.27, p = 0.285, R2 = 0.04, Table 1).

Discussion

We found that the total rainfall and the number of days with rain in May in east-central Poland increased significantly between 1999 and 2021, whereas no such trend as regards air temperature was discernible. Testing the influence of these two climatic variables revealed that the number of days with rain in May significantly delayed clutch initiation in Red-backed Shrikes. Over the 23 years of the study, this delay in nesting became as long as 5 days, the most probable cause of this in our opinion being the increase in rainfall (the greater number of days with rain in May) during that period. In contrast, higher May temperatures favoured the earlier nesting of the birds. The climatic variables under scrutiny here did not affect either clutch size or egg volume.

Although many bird species have advanced their start of egg laying and changed their breeding parameters in recent years (Costantini et al. 2010; Goodenough et al. 2010), some data indicate delayed nesting (e.g. Bates et al. 2022). In particular, changing brood parameters are not so clear-cut in long-distance migrants than in short-distance migrants, because they may be constrained by factors acting during the winter and migration periods (Tryjanowski et al. 2002; Laaksonen et al. 2006; Kallander et al. 2017). This probably applies to the Red-backed Shrike as well, because the influence of climatic factors on laying dates and reproductive parameters is highly ambiguous. In the Czech Republic, Hušek and Adamík (2008) found a 3- to 4-day shift towards earlier breeding and an increase in brood size by approximately 0.3 nestlings in the period 1964–2004. In western Poland in 1971–2002, Red-backed-Shrikes arrived at their breeding grounds significantly earlier, and the arrival date was correlated with the earliest first-egg date (Tryjanowski et al. 2004). On the other hand, the nesting dates for two periods (1905-1935 vs. 1985–1999) did not show any difference in the time of laying or clutch size in Poland (Tryjanowski 2002). Also, no significant correlation between the arrival date and the research period were recorded in north-western Croatia between 1991 and 2016 (Dolenec 2018). In contrast, the data we give in this paper point to quite a distinct delay in the start of nesting by Red-backed Shrikes in east-central Poland in the last 23 years, albeit without any trends whatsoever in clutch size or the mean egg volume in a clutch.

The effect of climate factors is fairly clearly reflected by changes in the clutch initiation date and breeding parameters. Our study has shown that higher May temperatures induce earlier nesting in Red-backed Shrikes, and identical relationships have also been found elsewhere (Matyjasiak 1995; Hušek and Adamík 2008; Hušek et al. 2009). The second dependence found in east-central Poland was the rainfall-induced delay in the onset of breeding, which also concurs with earlier studies (Hušek and Adamík 2008; Metzmacher and Van Nieuwenhuise 2012). Red-backed Shrikes appear to be particularly sensitive to rainfall (Tryjanowski et al. 2003). In east-central Poland, egg volume repeatability was related to the total rainfall immediately before egg laying (Golawski and Mitrus 2018) and breeding success was significantly dependent on the number of days with rain (Golawski and Golawska 2019). The partial loss of nestlings was also related to the total rainfall (Golawski 2006).

The energy status of laying females may deteriorate during inclement weather with low temperatures and rainfall because of the higher energetic cost of thermoregulation (Stevenson and Bryant 2000), and/or the reduced availability of food, especially for insectivorous species, resulting from delays in insect development and also their activity (Vicens and Bosch 2000; Arbeiter et al. 2016). A reduced food supply for laying females affects their condition, which in turn may delay nesting and result in poorer breeding parameters (Tryjanowski et al. 2004). The Red-backed Shrike is a mainly insectivorous species (Tryjanowski et al. 2003; Golawski 2006), so limited access to food can significantly affect the birds’ condition. Rainfall could therefore have driven the delay in clutch initiation in east-central Poland. Moreover, birds adjust their breeding season to the greatest availability of food when they are feeding their young (Both et al. 2006). A cooler and rainier spring means that insects develop later, especially orthopterans, which are a very important component of the shrikes’ diet in this region (Morelli et al. 2016; Golawski and Kondera 2023), so this may be a reason for the delay in clutch initiation. Delayed nesting can have serious consequences for birds, because females laying later in a given breeding season produce smaller clutches (Lack 1968); there will also be fewer re-nesting opportunities (Halupka et al. 2008). Red-backed Shrikes can re-nest if the first brood is lost, but this depends on the period of the breeding season when that loss occurred (Antczak et al. 2009), so later nesting can make a big difference to them.

Rainfall can also affect gonad development in birds. This depends on the light intensity (Dawson 2015), which during rainfall (when the sky is overcast) is less than on sunny days (Mumby et al. 2001; La and Park 2016) and the gonads then develop more slowly. In consequence, the birds' breeding season is delayed. However, we were unable to evaluate this dependence as we had no light intensity data for the study area to hand.

On the other hand, the number of eggs and their volume was independent of weather factors. Male Red-backed Shrikes feed their females before egg laying begins and set up larders where they store prey items, later to be consumed by the females (Yosef and Pinshow 2005). Such behaviour by the male to some extent compensates for the limited amount of food available to the female during poor weather, thereby enabling her to remain in relatively good condition, as demonstrated earlier in this region (Golawski et al. 2020). Moreover, the study area included habitats with extensive agriculture which are abundant in the shrikes’ potential prey (Golawski and Golawska 2008).

Conclusion

Our research shows that delayed clutch initiation by Red-backed Shrikes in the last 23 years has probably been a consequence of the increasingly frequent rainfall in this period. At the same time, air temperature did not display a clear trend. However, we emphasize that that our data are correlative: this does not mean that rainfall patterns are the underlying cause of changes in clutch metrics, merely that they are associated with each other. This is a good example of the fact that not only temperature but also rainfall can change the time of clutch initiation. Hence, predicting the long-term effects of global warming on the viability of east-central Polish populations of the Red-backed Shrike is difficult.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

References

Antczak M, Golawski A, Kuzniak S, Tryjanowski P (2009) Costly replacement – How do different stages of nest failure affect clutch replacement in the red-backed shrikes Lanius collurio? Ethol Ecol Evol 21:127–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2009.9522501

Arbeiter S, Schulze M, Tamm P, Hahn S (2016) Strong cascading effect of weather conditions on prey availability and annual breeding performance in European bee-eaters Merops apiaster. J Ornithol 157:155–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-015-1262-x

Bates JM, Fidino M, Nowak-Boyd L, Strausberger BM, Schmidt KA, Whelan CJ (2022) Climate change affects bird nesting phenology: Comparing contemporary field and historical museum nesting records. J Anim Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13683

Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecol Lett 15:365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x

BirdLife International (2021) Species factsheet: Lanius collurio. http://www.birdlife.org. Accessed 10 June 2022

Both C, Artemyev AV, Blaauw B et al (2004) Large-scale geographical variation confirms that climate change causes birds to lay earlier. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci 271:1657–1662. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.2770

Both C, Bouwhuis S, Lessells CM, Visser ME (2006) Climate change and population declines in a long-distance migratory bird. Nature 441:81–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04539

Bowers EK, Grindstaff JL, Soukup SS, Drilling NE, Eckerle KP, Sakaluk SK, Thompson CF (2016) Spring temperatures influence selection on breeding date and the potential for phenological mismatch in a migratory bird. Ecology 97:2880–2891. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1516

Brawn JD, Benson TJ, Stager M, Sly ND, Tarwater CE (2017) Impacts of changing rainfall regime on the demography of tropical birds. Nat Clim Chang 7:133–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3183

Bulluck L, Huber S, Viverette C, Blem C (2013) Age-specific responses to spring temperature in a migratory songbird: older females attempt more broods in warmer springs. Ecol Evol 3:3298–3306. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.673

Cavalcanti LMP, Paiva LV, França LF (2016) Efects of rainfall on bird reproduction in a semi-arid Neotropical region. Zoologia 33:e20160018. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1984-4689zool-20160018

Charmantier A, McCleery RH, Cole LR, Perrins C, Kruuk LEB, Sheldon BC (2008) Adaptive phenotypic plasticity in response to climate change in a wild bird population. Science 320:800–803. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1157174

Costantini D, Carello L, Dell’Omo G (2010) Patterns of covariation among weather conditions, winter North Atlantic Oscillation index, and reproductive traits in Mediterranean Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus). J Zool 280:177–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00649.x

Crick HQP, Sparks TH (1999) Climate change related to egg-laying trends. Nature 399:423–424. https://doi.org/10.1038/20839

Dawson A (2015) Annual gonadal cycles in birds: modeling the effects of photoperiod on seasonal changes in GnRH-1 secretion. Front Neuroendocrinol 37:52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2014.08.004

Degirmendzic J, Kozuchowski K, Zmudzka E (2004) Changes of air temperature and precipitation in Poland in the period 1951–2000 and their relationship to atmospheric circulation. Int J Climatol 24:291–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1010

Diehl B (1971) Productivity investigation of two types of meadows in the Vistula valley. Ekol Pol 19:235–248

Dolenec Z (2018) Comparison of arrival dates of the long-distance migratory Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio with spring air temperatures and year. Larus 20:33–40. https://doi.org/10.21857/ypn4oc8g19

Dore MHI (2005) Climate change and changes in global precipitation patterns: what do we know? Environ Int 31:1167–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2005.03.004

Drake A, Martin K (2018) Local temperatures predict breeding phenology but do not result in breeding synchrony among a community of resident cavity-nesting birds. Sci Rep 8:2756. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-20977-y

Drake A, Martin K (2020) Rainfall and nest site competition delay Mountain Bluebird and Tree Swallow breeding but do not impact productivity. Auk 137:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/ukaa006

Dunn PO, Møller AP (2014) Changes in breeding phenology and population size of birds. J Anim Ecol 83:729–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12162

Dunn PO, Winkler DW (1999) Climate change has affected the breeding date of tree swallows throughout North America. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci 266:2487–2490. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1999.0950

Golawski A (2006) Impact of weather on partial loss of nestlings in the red-backed shrike Lanius collurio in eastern Poland. Acta Ornithol 41:15–20. https://doi.org/10.3161/000164506777834705

Golawski A, Golawska S (2008) Habitat preference in territories of the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio and their food richness in an extensive agriculture landscape. Acta Zool Acad Sci Hung 54:89–97

Golawski A, Golawska S (2019) Weather and predation pressure: The case of the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio). Acta Zool Academ Sci Hung 65:371–379. https://doi.org/10.17109/AZH.65.4.371.2019

Golawski A, Kondera E (2023) Storing prey in larders affects nestling haematological condition in the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio). Ibis 165:153–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.13104

Golawski A, Meissner W (2008) The influence of territory characteristics and food supply on the breeding performance of the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) in an extensively farmed region of eastern Poland. Ecol Res 23:347–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11284-007-0383-y

Golawski A, Mitrus C (2018) Weather conditions influence egg volume repeatability in clutches of the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio. Zool Stud 57:e2. https://doi.org/10.6620/ZS.2018.57-02

Golawski A, Mroz E, Golawska S (2020) The function of food storing in shrikes: the importance of larders for the condition of females and during inclement weather. Eur Zool J 87:282–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750263.2020.1769208

Golawski A, Zduniak P (2022) Influence of researcher experience and fieldwork intensity on the probability of brood losses in sensitive species: The case of the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio. J Nat Conserv 69:126249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2022.126249

Goodenough AE, Hart AG, Stafford R (2010) Is adjustment of breeding phenology keeping pace with the need for change? Linking observed response in woodland birds to changes in temperature and selection pressure. Clim Change 102:687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-010-9932-4

Gray SB, Brady SM (2016) Plant developmental responses to climate change. Dev Biol 419:64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.07.023

Halupka L, Czyż B, Dominguez CMM (2020) The effect of climate change on laying dates, clutch size and productivity of Eurasian Coots Fulica atra. Int J Biometeorol 64:1857–1863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-020-01972-3

Halupka L, Dyrcz A, Borowiec M (2008) Climate change affects breeding of reed warblers Acrocephalus scirpaceus. J Avian Biol 39:95–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04047.x

Harris T, Franklin K (2000) Shrikes and Bush-Shrikes. Christopher Helm, London

Houghton J (2015) Global warming: The complete briefing. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hušek J, Adamík P (2008) Long-term trends in the timing of breeding and brood size in the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio in the Czech Republic, 1964–2004. J Ornithol 149:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-007-0222-5

Hušek J, Adamík P, Cepák J, Tryjanowski P (2009) The influence of climate and population size on the distribution of breeding dates in the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio). Ann Zool Fenn 46:439–450. https://doi.org/10.5735/086.046.0605

Irons RD, Harding Scurr A, Rose AP, Hagelin JC, Blake T, Doak DF (2017) Wind and rain are the primary climate factors driving changing phenology of an aerial insectivore. Proc Biol Sci 284:20170412. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0412

Kallander H, Hasselquist D, Hedenstrom A, Nord A, Smith HG, Nilsson JA (2017) Variation in laying date in relation to spring temperature in three species of tits (Paridae) and pied flycatchers Ficedula hypoleuca in southernmost Sweden. J Avian Biol 48:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01287

Krist M (2011) Egg size and offspring quality: a meta-analysis in birds. Biol Rev 86:692–716. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00166.x

La HS, Park K (2016) The evident role of clouds on phytoplankton abundance in Antarctic Coastal Polynyas. Terr Atmos Ocean Sci 27:293–301. https://doi.org/10.3319/TAO.2015.11.30.01(Oc)

Laaksonen T, Ahola M, Eeva T, Väisänen RA, Lehikoinen E (2006) Climate change, migratory connectivity and changes in laying date and clutch size of the pied flycatcher. Oikos 114:277–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2006.0030-1299.14652.x

Lack D (1968) Ecological adaptations for breeding in birds. Methuen, London

Lessells CM, Boag PT (1987) Unrepeatable repeatabilities: a common mistake. Auk 104:116–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/4087240

Lindenmayer DB, Likens GE, Andersen A et al (2012) Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecol 37:745–757. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x

Matyjasiak P (1995) Breeding ecology of the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) in Poland. Proc West Found Vertebr Zool 6:228–234

Mcdermott ME, Degroote LW (2016) Long-term climate impacts on breeding bird phenology in Pennsylvania, USA. Glob Change Biol 22:3304–3319. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13363

Metzmacher M, Van Nieuwenhuise D (2012) Population dynamic of Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) in south-eastern Belgium: modelling of climate influence. Rev Écol 67:1–22

Morelli F, Mroz E, Pruscini F, Santolini R, Golawski A, Tryjanowski P (2016) Habitat structure, breeding stage and sex affect hunting success of breeding Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio). Ethol Ecol Evol 28:136–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2015.1022907

Møller AP, Flensted-Jensen E, Klarborg K, Mardal W, Nielsen JT (2010) Climate change affects the duration of the reproductive season in birds. J Anim Ecol 79:777–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01677.x

Mumby PJ, Chisholm JRM, Edwards AJ, Andrefouet S, Jaubert J (2001) Cloudy weather may have saved Society Island reef corals during 1998 ENSO event. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 222:209–216. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps222209

Oppel S, Cassini A, Fenton C, Daley J, Gray G (2014) Population status and trend of the critically endangered Montserrat Oriole. Bird Conserv Int 24:252–261. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270913000373

Potti J (2008) Temperature during egg formation and the effect of climate warming on egg size in a small songbird. Acta Oecol 33:387–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actao.2008.02.003

Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Radchuk V, Reed T, Teplitsky C et al (2019) Adaptive responses of animals to climate change are most likely insufficient. Nat Commun 10:3109. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10924-4

Schneider NA, Griesser M (2009) Influence and value of different water regimes on avian species richness in arid inland Australia. Biodivers Conserv 18:457–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-008-9501-6

Shaw P (2017) Rainfall, leafing phenology and sunrise time as potential Zeitgeber for the bimodal, dry season laying pattern of an African Rain Forest Tit (Parus fasciiventer). J Ornithol 158:263–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1395-6

Shipley JR, Twining CW, Taff CC, Vitousek MN, Flack A, Winkler DW (2020) Birds advancing lay dates with warming springs face greater risk of chick mortality. PNAS 117:25590–25594. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2009864117

StatSoft Inc (2014) Statistica (data analysis software system, version 12.0). www.statsoft.com. Accessed 25 Feb 2022

Stevenson IR, Bryant DM (2000) Climate change and constraints on breeding. Nature 406:366–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/35019151

Surmacki A, Kuczynski L, Tryjanowski P (2006) Eggshell patterning in the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio: relation to egg size and potential function. Acta Ornithol 41:145–151. https://doi.org/10.3161/000164506780143861

Townsend AK, Sillett TS, Lany NK, Kaiser SA, Rodenhouse NL, Webster MS, Holmes RT (2013) Warm springs, early lay dates, and double brooding in a North American migratory songbird, the black-throated blue warbler. PLoS ONE 8:e59467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059467

Tryjanowski P (2002) A long-term comparison of laying date and clutch size in the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) in Silesia, Southern Poland. Acta Zool Acad Sci Hung 48:101–106

Tryjanowski P, Golawski A, Kuźniak S, Mokwa T, Antczak M (2007) Disperse or stay? Exceptionally high breeding-site infidelity in the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio. Ardea 95:316–320. https://doi.org/10.5253/078.095.0214

Tryjanowski P, Karg MK, Karg J (2003) Diet composition and prey choice by the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio in western Poland. Belg J Zool 133:157–162

Tryjanowski P, Kuzniak S (1999) Effect of research activity on the success of Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio nests. Ornis Fenn 76:41–43

Tryjanowski P, Kuzniak S, Sparks T (2002) Earlier arrival of some farmland migrants in western Poland. Ibis 144:62–68. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0019-1019.2001.00022.x

Tryjanowski P, Sparks TH (2001) Is the detection of the first arrival date of migrating birds influenced by population size? A case study of the Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio. Int J Biometeorol 45:217–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-001-0112-0

Tryjanowski P, Sparks TH, Kuczyński L, Kuźniak S (2004) Should avian egg size increase as a result of global warming? A case study using the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio). J Ornithol 145:264–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-004-0035-8

Vicens N, Bosch J (2000) Weather-dependent pollinator activity in an apple orchard, with special reference to Osmia cornuta and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae and Apidae). Environ Entomol 29:413–420. https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-29.3.413

Wesołowski T (1986) Card index of nests and broods. University of Wrocław, Instructions for co-workers

Yosef R, Pinshow B (2005) Impaling in true shrikes (Laniidae): A behavioral and ontogenic perspective. Behav Processes 69:363–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2005.02.023

Acknowledgements

We thank Emilia Mróz for her field assistance. We are grateful to Peter Senn for the English

language editing and to Kamil Krynski for his help in preparing the map of the study area. We thank the three anonymous referees for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Poland (Grant No. 76/20/B)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Provided in the manuscript

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests

Supplementary information

Fig. S1

Relationship between weather factors and year: a) mean May air temperature, b) total precipitation, c) number of days with rain (data for meteorological station in Siedlce, east-central Poland) (DOCX 261 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golawski, A., Golawska, S. Delayed egg-laying in Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio in relation to increased rainfall in east-central Poland. Int J Biometeorol 67, 717–724 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-023-02450-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-023-02450-2