Abstract

Background

Sleep disorders are one of the major public health problems, which can potentially induce inflammation and exacerbate disease activity, resulting in compromised sleep quality. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors associated with sleep disorders among patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods

Between March 2023 and February 2024, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index was employed to assess sleep quality in both IBD patients and healthy control subjects. Univariate and multivariate analysis were performed to identify the risk factors associated with SD in IBD patients.

Results

Overall, 208 IBD patients [150 Crohn’s disease (CD) and 58 ulcerative colitis (UC)] and 199 healthy individuals were included. Sleep disorders were observed in 59.6% of patients with IBD, with a higher prevalence among females (63.5%) compared to males (56.9%) (P = 0.476). The prevalence of sleep disorders in IBD patients was significantly higher than that found in healthy controls (37.7%) (all P < 0.01). The prevalence of sleep disorders among CD and UC patients was 58% and 63.8%, respectively (P = 0.291). The multivariate analysis revealed that older age (OR, 1.070; 95% CI: 1.035–1.105, P = 0.000), smoking (OR, 2.698; 95% CI: 1.089–6.685, P = 0.032), and depression (OR, 4.779; 95% CI: 1.915–11.928, P = 0.001) were risk factors for sleep disorders in IBD patients. However, higher body mass index (OR, 0.879; 95% CI: 0.790–0.977, P = 0.017) was identified as a protective factor.

Conclusion

Sleep disorders are common among IBD patients regardless of activity levels. Smoking and depression are the major risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic, nonspecific inflammatory condition affecting the gastrointestinal tract [1]. The primary therapeutic objective in IBD management is enhancing patients’ quality of life through disease activity control and remission maintenance [2]. Various environmental factors, such as smoking, sleep disorders, and depression, are implicated in the etiology of IBD [3]. Among these factors, sleep disorders have emerged as significant risk factors [odds ratio (OR): 3.09] for IBD exacerbation, leading to heightened disease severity, surgical and hospitalization risks, and diminished quality of life [4, 5].

Sleep disorders typically encompass conditions affecting sleep or manifesting as clinical symptoms during sleep, often linked to the sleep cycle. Certain sleep disorders are correlated with physical ailments and stress responses, spanning acute and chronic conditions, as well as physical and psychological disorders, posing risks to patients’ well-being, quality of life, and potentially leading to incidents like traffic accidents that compromise public safety [6]. Currently, the diagnostic methods for sleep disorders include subjective and objective measurements. Subjective measurements include the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Multisystem Inventory and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and objective measurements such as polysomnography and wrist actigraphy [7]. Previous research has validated the PSQI as a highly sensitive and specific tool for diagnosing sleep disorders in patients with IBD [8, 9].

Sleep disorders are highly prevalent in IBD patients, with reported rates ranging from 32.2% to 82% [4, 10,11,12,13,14]. Studies have demonstrated that sleep disorders can influence the progression as well as the relapse of IBD by affecting the immune system [11, 13, 15]. Nevertheless, in active IBD, symptoms like abdominal pain and diarrhea can disrupt sleep and exacerbate sleep disorders, resulting in a self-perpetuating cycle [11, 16]. They can influence and promote each other and form a vicious circle. In addition, anxiety and depression are common in IBD, which play an important role in the occurrence and development of sleep disorders [13, 15, 17, 18]. Despite this, no research has simultaneously examined the relationship between sleep disorders and both CD and UC, as well as their respective disease activity and psychological functioning. Thus, this study aimed to investigate the prevalence and risk factors of sleep disorders in IBD patients.

Methods

This study, conducted at a single center, employed trained investigators to administer anonymous questionnaires to participants and guide them through the completion process. Each questionnaire was coded for anonymity. Simultaneously, physicians recorded disease activity scores using corresponding codes in a separate document. The study was conducted in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki, and approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, adhering to the guidelines outlined in “Strengthening epidemiological observation and reporting” (Table S1) [19].

Participants

Consecutive patients diagnosed with IBD at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between March 2023 and February 2024 were included, while healthy individuals undergoing physical examinations at the center during the same period served as controls.

Diagnosis of IBD

The diagnosis of IBD relies primarily on a comprehensive assessment of clinical, laboratory, imaging, endoscopic, and histopathological evidence while excluding infectious and noninfectious colitis [20].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria stipulate participants must be over 18 years old, have attended multiple visits (with only the initial visit considered), possess the capacity to comprehend and complete scales, consent to participate, and sign the informed consent form. Exclusion criteria encompass individuals with mental illness, inability to comprehend or complete scales, pregnancy, concurrent serious conditions like respiratory or renal failure, tumors, restless legs syndrome, engagement in shift work, or use of specific medications such as antiallergics, anesthetics, or pain regulators.

Demographic and disease information

Clinical data of the subjects, encompassing sex, age, height, weight, education level, marital status, occupation, address, smoking and drinking history, disease type and duration, history of IBD-related surgery, current medication use (including corticosteroids, 5-aminosalicylic acids, immunosuppressants, biologics, and psychotropic drugs), and IBD-related complications, were extracted from the hospital’s medical records system.

Severity of disease

CD severity was assessed using the best Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI), with scores < 150 indicating remission and scores ≥ 150 indicating active disease, further categorized as mildly active (150–220), moderately active (221–450), and severely active (> 450) [21]. The severity of UC was determined using the improved Mayo scale, with scores ≤ 2 and no single sub-score > 1 denoting remission, scores 3–5 indicating mild activity, 6–10 indicating moderate activity, and 11–12 indicating severe activity [22].

Evaluation of anxiety and/or depression

The psychological function of the subjects was assessed using the verified and reliable Chinese version of the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS). HADS comprises two subscales: anxiety and depression, each scored from 0 to 21. Scores greater than or equal to 8 indicate the presence of anxiety and/or depression [23].

Evaluation of sleep disorders

The sleep function of the subjects was evaluated using the validated Chinese version of PSQI [24]. Previous studies have shown a correlation between the PSQI total score and objective sleep measurements such as polysomnography [25]. The PSQI consists of seven components: sleep quality, sleep duration, sleep latency, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, sedative medication use, and daytime dysfunction. Each question is scored from 0 to 3, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher total PSQI score indicates lower sleep quality, with a score greater than 5 indicating the presence of sleep disturbances [26].

Outcome

The main outcome of the study was to compare the prevalence of sleep disorders between IBD patients and healthy controls and to investigate the risk factors associated with sleep disorders in IBD patients.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (v. 26, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median and interquartile range, or frequency and percentage as required. Between-group comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U-test or chi-square test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to assess the risk factors for sleep disorders. Variables with a P-value less than 0.20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate regression. Stepwise regression was utilized to identify the optimal model of risk factors independently associated with sleep disorders, and the results were reported as OR with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Participant’s characteristics

A total of 208 IBD [including 150 CD (mean age: 36 and 87 males) and 58 UC (mean age: 40 and 36 males)] and 199 healthy individuals (mean age: 36 and 120 males) were included. The basic characteristics of all the participants were shown in Table 1. No significant differences in demographic characteristics were observed among, IBD patients and healthy controls. The disease features of IBD were shown in Table 2. The mean CDAI score of CD was 162.67, and 82 CDs (52.4%) were active, of which mild, moderate, and severe activities accounted for 23.3%, 30%, and 1.3%, respectively, and mean disease duration was 4.97 years. The mean Mayo score of UC was 6.62, and 49 UCs (84.5%) were active, of which mild, moderate, and severe activities accounted for 32.8%, 25.9%, and 25.9%, respectively, and mean disease duration was 5.34 years.

As shown in Table 1, 67 (44.7%) CDs and 20 (35.4%) UCs had anxiety, both of which were significantly higher than those in healthy controls (23.1%, P < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of anxiety between CD and UC patients (P = 0.152). Twenty-seven (18%) CD and 11 (19%) UC patients had depression, which was significantly higher than that in the healthy controls (4.5%, P < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of depression between CD and UC patients (P = 0.361).

Prevalence of sleep disorders

The overall PSQI scores of CD (6.71 ± 3.53) and UC (6.90 ± 3.51) were significantly higher than those of the controls (4.78 ± 3.03) (P < 0.01). There was no difference in overall PSQI scores between CD and UC (P = 0.734). The scores for each component of PSQI were shown in Table 3. The sleep duration > 7 h in the CD and UC was significantly lower than that in controls (all P < 0.05), and the habitual sleep efficiency was significantly lower than that in controls (all P < 0.05). Sleep medication use was higher than controls (all P < 0.01), daytime dysfunction was higher than controls (all P < 0.01), and sleep quality was worse than controls (all P < 0.01). There were no significant differences in sleep disturbance of CD and UC compare with controls and in sleep latency of CD and controls (P = 0.146, P = 0.204, and P = 0.214, respectively). The sleep latency of UC was significantly higher than that of controls (P < 0.01). There was no difference in PSQI scores between CD and UC (P = 0.597, P = 0.189, P = 0.933, P = 0.620, P = 0.630, P = 0.063, and P = 0.561).

As shown in Fig. 1 and Table 4, we found that 59.6% (124/208) of IBD suffered from sleep disorders, of which 63.5% of females and 56.9% of males were significantly higher than those in controls (37.7%) (P < 0.01), but there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence rate between female and male patients (P = 0.476). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of sleep disorders between CD and UC, 58% (87/150) and 63.8% (37/58), respectively (P = 0.291), but both were significantly higher than those in controls (all P < 0.01). The prevalence of sleep disorders in active IBD was higher than that in remission (66.4% and 48.1%, respectively) (P < 0.05), which was significantly higher than that in controls (all P < 0.01). The prevalence of sleep disorders in mildly, moderately, and severely active IBD was 59.3%, 70%, and 76.5%, respectively, significantly higher than that in controls (all P < 0.01). The prevalence of sleep disorders increased with the increase of active disease index, but there was no statistically significant difference between any two pairs (all P > 0.05).

In CD, the prevalence of 61.9% in women and 55.2% in men was higher than that in the control (all P < 0.05), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.410). The prevalence of sleep disorders in remission, mildly, moderately, and severely active CD, was 45.6%, 62.9%, 73.3%, and 50%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those in controls except for severely active CD (all P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between the prevalence of severely active CD and the control (P = 1.000). In addition to the severely active CD, the prevalence of sleep disorders increased with the increase of active disease index. However, there was no significant difference between any pairings (all P > 0.05) except the prevalence of moderately active CD and CD in remission (P < 0.01).

In UC, the prevalence of sleep disorders in women and men were 68.2% and 61.1%, respectively, which was higher than those in the control (all P < 0.05), but there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.587). The prevalence of sleep disorders in remission, mildly, moderately, and severely active UC, was 66.7%, 52.6%, 60%, and 80%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those in the control (all P < 0.01), but there was no statistical significance compared with CD (all P > 0.05). However, there was no significant difference between any pairings (all P > 0.05).

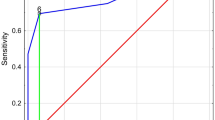

Risk factors of sleep disorders

In univariate analysis, older age (OR, 1.056; 95% CI: 1.025–1.089, P = 0.000), occupation (OR, 0.230; 95% CI: 0.062–0.854, P = 0.028), longer disease duration (OR, 1.102; 95% CI: 1.017–1.193, P = 0.018), active IBD (OR, 2.138; 95% CI: 1.202–3.801, P = 0.010), higher active IBD index (OR, 1.285; 95% CI: 1.085–1.951, P = 0.041), anxiety (OR, 2.360; 95% CI: 1.314–4.238, P = 0.004), and depression (OR, 3.667; 95% CI: 1.530–8.787, P = 0.004) were associated with sleep disorders.

In multivariate analysis, older age (OR, 1.070; 95% CI: 1.035–1.105, P = 0.000), smoking (OR, 2.698; 95% CI: 1.089–6.685, P = 0.032), and depression (OR, 4.779; 95% CI: 1.915–11.928, P = 0.001) were identified as risk factors for sleep disorders (Table 5), and lower BMI (OR, 0.879; 95% CI: 0.790–0.977, P = 0.017) was considered as a protective factor.

Discussion

Sleep disorders significantly impact the quality of life in patients with IBD. Our study revealed a notably high prevalence of sleep disorders in this population, with 60% of patients experiencing sleep disorders, a rate significantly higher than that observed in the general population, consistent with existing literature [10, 12, 14,15,16, 27,28,29]. Previous studies [10, 13] have highlighted that while disease-related symptoms play a crucial role in sleep disruption, the prevalence of sleep disorders remains elevated among IBD patients even during remission. Sleep deprivation not only elevates the risk of disease symptom manifestation and potential recurrence but also underscores the persistence of elevated sleep disorders prevalence in IBD patients during remission compared to healthy individuals. After control for confounding factors such as depression, fatigue, and corticosteroids use, Ali et al. used endoscopy and histology to assess disease activity, and found a recurrence rate of 47% at 3 months and 67% at 6 months in patients with sleep disorders and a recurrence rate of 0% at both 3 and 6 months in patients without sleep disorders in remission [16]. Ananthakrishnan et al. reported a twofold increase in the risk of disease recurrence within 6 months for patients with subjective sleep disorders [15]. Uemura et al. conducted a 1-year follow-up of IBD patients and showed that 60.8% of IBD recurrent patients had sleep disorders, while only 34.1% of patients without recurrence had sleep disorders, which also suggested that sleep disorders may be a risk factor for IBD recurrence [5]. Additionally, zoological studies have shown that both acute and chronic sleep deprivation can exacerbate colitis-related inflammation [30, 31]. Therefore, addressing sleep disorders presents an opportunity not only to enhance quality of life but also to improve overall clinical outcomes of IBD patients.

The prevalence of sleep disorders among IBD patients showed no significant disparity based on disease type and sex, indicating minimal influence from these factors. Further examination of the PQSI component scores indicated no discernible variance in sleep disturbance between patients with CD and UC in comparison to controls. Similarly, no distinctions in sleep latency scores were observed between CD patients and healthy controls, implying that this component did not primarily impact their sleep functionality. Moreover, our findings revealed a positive correlation between disease activity and the prevalence of sleep disorders in IBD patients. Subgroup analysis based on disease type demonstrated a similar trend in CD but not in UC, potentially due to the limited number of UC patients included in the study (58). Notably, IBD patients (both CD and UC) exhibited significantly higher rates of anxiety and depression than healthy controls, aligning with prior research indicating elevated likelihood of anxiety and/or depression symptoms in IBD patients compared to healthy controls [32]. Additionally, a study revealed that all IBD patients with depression experienced sleep disorders, while anxiety did not significantly impact sleep disorders. This suggests that psychological factors may be more closely linked to sleep disorders in IBD patients than the disease itself [18].

Our study identified several factors associated with sleep disorders in IBD patients, including older age, occupation, longer disease duration, active IBD, higher disease activity index, anxiety, and depression. Prior research has linked sleep disorders in IBD patients to depression, anxiety, active disease, age over 52, long duration of CD (> 12 years), current corticosteroid use, current anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy, and past/current smoking habits [4, 10,11,12,13, 15]. In a multivariate analysis by Wilson et al., sleep disorders in IBD patients was found to be independent of symptoms like nighttime abdominal pain and diarrhea, instead of being associated with systemic inflammation in IBD [13]. Subsequent multivariate analysis from our study revealed that older age, lower BMI, smoking, and depression were risk factors for sleep disorders. Notably, the association of older age, smoking, and depression as risk factors has been extensively documented in previous literature [11, 18]. Of interest, we observed that a lower BMI was a risk factor for sleep disorders, contrary to findings in studies involving adolescents and postmenopausal women where higher BMI correlated with increased sleep disorders risk [33, 34]. This discrepancy may stem from the typically lower BMI of IBD patients compared to the general population, suggesting that within limits, an increase in BMI could potentially enhance sleep quality in IBD patients [35]. IBD is characterized by chronic progressive gut inflammation leading to structural and functional gut impairment, resulting in significant gastrointestinal symptoms. Consequently, IBD patients are susceptible to malnutrition and weight loss due to various factors such as dietary restrictions, malabsorption, chronic diarrhea, and intestinal bacterial overgrowth [36, 37], highlighting the importance of nutritional support and inflammation control in enhancing sleep quality and maintaining disease remission for IBD patients.

There are limitations to consider. Firstly, the sample size is relatively small, particularly among UC patients, and the questionnaires completed by the study participants may suffer from subjectivity and memory errors. However, the reliability of the research results is supported by the well-validated PQSI. Secondly, this study adopts a cross-sectional design, rendering it capable of assessing associations but unable to establish causation. Lastly, active versus inactive disease was determined using the CDAI and improved Mayo scale instead of more objective indicators like mucosal appearance. Nonetheless, our findings reveal a high prevalence of sleep disorders in IBD patients. Future investigations should encompass larger-scale studies incorporating polysomnography and other objective measures to further explore the nature of sleep disorders in IBD patients and its underlying mechanisms.

Conclusion

The prevalence of sleep disorders is higher in IBD patients than health individuals. Older age, lower BMI, smoking, and depression are risk factors for developing sleep disorders in IBD patients. Clinicians should screen the presence of sleep disorders in IBD patients, providing strengthen nutrition support strategies, guiding smoking cessation, and evaluating IBD patients’ psychological function.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

References

Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI et al (2017) Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet (London, England) 390:2769–2778

Swanson GR, Burgess HJ, Keshavarzian A (2011) Sleep disturbances and inflammatory bowel disease: a potential trigger for disease flare? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 7:29–36

Ananthakrishnan AN (2015) Epidemiology and risk factors for IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 12:205–217

Sofia MA, Lipowska AM, Zmeter N, Perez E, Kavitt R, Rubin DT (2020) Poor sleep quality in Crohn’s disease is associated with disease activity and risk for hospitalization or surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis 26:1251–1259

Uemura R, Fujiwara Y, Iwakura N, Shiba M, Watanabe K, Kamata N et al (2016) Sleep disturbances in Japanese patients with inflammatory bowel disease and their impact on disease flare. Springerplus 5:1792

Grandner MA (2022) Sleep, health, and society. Sleep Med Clin 17:117–139

Canakis A, Qazi T (2020) Sleep and fatigue in IBD: an unrecognized but important extra-intestinal manifestation. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 22:8

Sobolewska-Wlodarczyk A, Wlodarczyk M, Banasik J, Gasiorowska A, Wisniewska-Jarosinska M, Fichna J (2018) Sleep disturbance and disease activity in adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Phys Pharmacol 69(3). https://doi.org/10.26402/jpp.2018.3.09

Michalopoulos G, Vrakas S, Makris K, Tzathas C (2018) Association of sleep quality and mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission. Ann Gastroenterol 31:211–216

Salwen-Deremer JK, Smith MT, Haskell HG, Schreyer C, Siegel CA (2022) Poor sleep in inflammatory bowel disease is reflective of distinct sleep disorders. Dig Dis Sci 67:3096–3107

Qazi T, Farraye FA (2019) Sleep and inflammatory bowel disease: an important bi-directional relationship. Inflamm Bowel Dis 25:843–852

Gingold-Belfer R, Peled N, Levy S, Katz N, Niv Y, Fass R et al (2014) Impaired sleep quality in Crohn’s disease depends on disease activity. Dig Dis Sci 59:146–151

Wilson RG, Stevens BW, Guo AY, Russell CN, Thornton A, Cohen MA et al (2015) High C-reactive protein is associated with poor sleep quality independent of nocturnal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 60:2136–2143

Graff LA, Vincent N, Walker JR, Clara I, Carr R, Ediger J et al (2011) A population-based study of fatigue and sleep difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17:1882–1889

Ananthakrishnan AN, Long MD, Martin CF, Sandler RS, Kappelman MD (2013) Sleep disturbance and risk of active disease in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 11:965–971

Ali T, Madhoun MF, Orr WC, Rubin DT (2013) Assessment of the relationship between quality of sleep and disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19:2440–2443

Stevens BW, Borren NZ, Velonias G, Conway G, Cleland T, Andrews E et al (2017) Vedolizumab therapy is associated with an improvement in sleep quality and mood in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci 62:197–206

Marinelli C, Savarino EV, Marsilio I, Lorenzon G, Gavaruzzi T, D’Incà R et al (2020) Sleep disturbance in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and risk factors - a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 10:507

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2014) The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg (London, England) 12:1495–1499

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Group CSoG, Chinese Medical Association (2021) Chinese consensus on diagnosis and treatment in inflammatory bowel disease (2018, Beijing). J Digest Dis 22:298-317

Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr (1976) Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index national cooperative Crohn’s disease study. Gastroenterology 70:439–444

Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J et al (2005) Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 353:2462–2476

Sun ZX, Liu HX, Jiao LY, Zhou T, Yang LN, Fan JY (2017) Reliability and validity of hospital anxiety and depression scale. Chin J Clin(Electronic Edition) 11:198–201

Zheng B, Li M, Wang KL, Lv J (2016) [Analysis of the reliability and validity of the Chinese version of Pittsburgh sleep quality index among medical college students]. Beijing da xue xue bao Yi xue ban = Jo Peking Univ Health Sci 48:424–8.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Hoch CC, Yeager AL, Kupfer DJ (1991) Quantification of subjective sleep quality in healthy elderly men and women using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). Sleep 14:331–338

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28:193–213

Iskandar HN, Linan EE, Patel A, Moore R, Lasanajak Y, Gyawali CP et al (2020) Self-reported sleep disturbance in Crohn’s disease is not confirmed by objective sleep measures. Sci Rep 10:1980

Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, DeWalt DA, Kinneer PM, Chen W et al (2014) Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: Official Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 12:1315–23.e2

Ranjbaran Z, Keefer L, Farhadi A, Stepanski E, Sedghi S, Keshavarzian A (2007) Impact of sleep disturbances in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22:1748–1753

Wang D, Yin H, Wang X, Wang Z, Han M, He Q et al (2022) Influence of sleep disruption on inflammatory bowel disease and changes in circadian rhythm genes. Heliyon 8:e11229

Park YS, Chung SH, Lee SK, Kim JH, Kim JB, Kim TK et al (2015) Melatonin improves experimental colitis with sleep deprivation. Int J Mol Med 35:979–986

Bisgaard TH, Allin KH, Keefer L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Jess T (2022) Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 19:717–726

Naufel MF, Frange C, Andersen ML, Girão M, Tufik S, Beraldi Ribeiro E et al (2018) Association between obesity and sleep disorders in postmenopausal women. Menopause (New York, NY) 25:139–144

Geva N, Pinhas-Hamiel O, Frenkel H, Shina A, Derazne E, Tzur D, et al. (2020) Obesity and sleep disorders: a nationwide study of 1.3 million Israeli adolescents. Obesity research & clinical practice. 14:542–7

Opstelten JL, de Vries JHM, Wools A, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B, Witteman BJM (2019) Dietary intake of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison with individuals from a general population and associations with relapse. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland) 38:1892–1898

Balestrieri P, Ribolsi M, Guarino MPL, Emerenziani S, Altomare A, Cicala M (2020) Nutritional aspects in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nutrients 12(2):372

Lepp J, Höög C, Forsell A, Fyrhake U, Lördal M, Almer S (2020) Rapid weight gain in infliximab treated Crohn’s disease patients is sustained over time: real-life data over 12 months. Scand J Gastroenterol 55:1411–1418

Funding

This study was supported by the 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. ZYGD23030).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z.Z., X.Z.S., H.T., and H.L. conceptualized, designed, and drafted the manuscript. J.Z. and X.Z.S. performed article search, data extraction, and quality assessment. J.Z., X.Z.S., X.N.S, Y.L.S., H.T. and H.L. conducted data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the amended Declaration of Helsinki, and approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, JZ., Song, XZ., Song, XN. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of sleep disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. Int J Colorectal Dis 39, 140 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-024-04712-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-024-04712-w