Abstract

Here we present the first multi-model ensemble of regional climate simulations at kilometer-scale horizontal grid spacing over a decade long period. A total of 23 simulations run with a horizontal grid spacing of \(\sim \)3 km, driven by ERA-Interim reanalysis, and performed by 22 European research groups are analysed. Six different regional climate models (RCMs) are represented in the ensemble. The simulations are compared against available high-resolution precipitation observations and coarse resolution (\(\sim \) 12 km) RCMs with parameterized convection. The model simulations and observations are compared with respect to mean precipitation, precipitation intensity and frequency, and heavy precipitation on daily and hourly timescales in different seasons. The results show that kilometer-scale models produce a more realistic representation of precipitation than the coarse resolution RCMs. The most significant improvements are found for heavy precipitation and precipitation frequency on both daily and hourly time scales in the summer season. In general, kilometer-scale models tend to produce more intense precipitation and reduced wet-hour frequency compared to coarse resolution models. On average, the multi-model mean shows a reduction of bias from \(\sim \,\) −40% at 12 km to \(\sim \,\) −3% at 3 km for heavy hourly precipitation in summer. Furthermore, the uncertainty ranges i.e. the variability between the models for wet hour frequency is reduced by half with the use of kilometer-scale models. Although differences between the model simulations at the kilometer-scale and observations still exist, it is evident that these simulations are superior to the coarse-resolution RCM simulations in the representing precipitation in the present-day climate, and thus offer a promising way forward for investigations of climate and climate change at local to regional scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The need for climate change information at regional and local scales that are not resolved and represented by global climate models (GCMs) has led to the development of various downscaling techniques (Giorgi et al. 2009; Maraun and Widmann 2018). Dynamical downscaling makes use of limited-area high-resolution regional climate models (RCMs) nested into global model output (Giorgi et al. 2009). In the last \(\sim \)30 years, RCMs have been used in a series of large collaborative projects like PRUDENCE (Christensen et al. 2007), ENSEMBLES (van der Linden and Mitchell 2009), PRINCIPLES and EURO-CORDEX (Jacob et al. 2014), in which the horizontal grid spacing was decreased from 50 km in PRUDENCE to 25 km in ENSEMBLES and to 12 km in PRINCIPLES and EURO-CORDEX (Giorgi 2019). These projects provide coordinated ensembles of climate simulations over Europe, which have been used in assessing the uncertainty of RCM projections and in impact assessment studies but also to recognize the systematic model behavior and remaining biases. These results show that increased resolution of RCMs adds value in comparison to GCMs (see e.g., Torma et al. 2015), but no clear benefit of decreasing the grid spacing of RCMs from 50 to 12 km is found for simulation of seasonal mean quantities (Kotlarski et al. 2014). Furthermore, the results show that biases related to heavy precipitation intensity and frequency still persists especially at the sub-daily timescales (e.g., Brockhaus et al. 2008; Frei et al. 2003).

Over the last decade, many studies have been exploring RCMs at so-called convection-permitting, convection-resolving, convection-allowing or kilometer-scale grid spacing (Ban et al. 2014; Kendon et al. 2012, 2014; Leutwyler et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2017; Berthou et al. 2018; Fumière et al. 2019). The defining characteristics of these types of simulations are that deep convection parameterizations are turned off and they are run at grid spacings below 4 km. These studies have been conducted over diverse geographical regions such as North America (Liu et al. 2017), Europe (Leutwyler et al. 2017; Berthou et al. 2018), Africa (Kendon et al. 2019b) and Eastern China (Yun et al. 2019), and focus on both present day, as well as projected future, conditions. While the numerical weather prediction community has long appreciated the benefits of explicitly resolving convection and other (thermo)dynamical processes, it is only with recent computational advances that climate time scales (i.e., decade or longer) have been within reach. As more and more studies are performed, the evidence continues to mount that kilometer-scale modeling confers such significant advantages in representing climate and that the costs are worth it if the focus is on local to regional scales.

Prein et al. (2015) provides a summary of results, challenges and prospects related to convection-permitting climate modelling from an ensemble of opportunity consisting of most convection-permitting modelling studies available at that moment. The ensemble of studies mixed different models, experiment designs, domain locations, resolutions and sizes, time periods and nesting strategies. Regarding precipitation, they found added value especially at the smaller spatial and temporal scales. Namely, they report improvements in the representation of hourly extreme precipitation; in the timing of the onset and peak of the diurnal cycle of precipitation; in the spatial structure of precipitation; and in the wet-day/hour frequency (Kendon et al. 2012; Prein et al. 2013; Ban et al. 2014). Improvements in these precipitation features occur mainly during summer, when convection plays an increased role, especially in the mid-latitudes. More recent studies have extended evaluation beyond precipitation and have shown that the kilometer-scale grid leads to improvement in the simulation of clouds (Hentgen et al. 2019), local wind systems like sea-breezes (Belušić et al. 2018) and snow cover (Lüthi et al. 2019; Ikeda et al. 2010; Rasmussen et al. 2011, 2014; Liu et al. 2017).

Recently, an ensemble of twelve km-scale projections, spanning three 20-year periods, were carried out as part of the UK Climate Projections project (Kendon et al. 2019a). These ensemble simulations provide an initial estimate of uncertainties at km-scales, but only sample uncertainty in the driving model physics parameters and not in the convection-resolving model itself. To date, no study has investigated uncertainties in climate simulations at km-scales in a coordinated multi-model framework.

The coordinated regional climate downscaling experiment (CORDEX; Gutowski et al. 2016) Flagship Pilot Study (CORDEX-FPS) on Convective Phenomena over Europe and the Mediterranean (Coppola et al. 2019) has recently setup the first coordinated multi-model framework to explore convection-resolving climate simulation capabilities and uncertainties in a systematic manner. The greater Alpine region has been selected as a common target area for this experiment. Many regional modelling groups have tested their models and run simulations for the standard FPS domain over the last 2 years. A large part of simulations for the present-day climate driven by ERA-Interim reanalysis are completed, but some of them are still ongoing, especially those forced by historical and scenario global climate simulations. The resulting database will be an unprecedented resource to explore convection-resolving climate modelling uncertainties and to drive future model development.

In this manuscript, we present the first multi-model ensemble of decade-long climate evaluation simulations at convection-resolving resolution available from the CORDEX-FPS on convective phenomena. The main goal of this study is to evaluate this multi-model ensemble against available high-resolution observations and coarse resolution regional climate simulations for the representation of precipitation in all seasons. The specific objectives are the following:

-

1.

Are there systematic differences in precipitation biases between the two types of simulations (convection-resolving at kilometer-scale grid spacing versus parameterized-convection at horizontal grid spacings greater than 12 km)?

-

2.

If yes for the above, do convection-resolving climate models improve the simulation of precipitation?

-

3.

Does the multi-model ensemble approach at kilometer-scale grid spacing reduce uncertainty estimates in comparison to coarse resolution models?

The current manuscript presents the first part (out of two) of the first multi-model ensemble of regional climate simulations at kilometer-scale resolution and focuses on the evaluation of precipitation in present-day climate. Thus, here we use only ERA-Interim driven simulations. The second part of this series (Pichelli et al. 2021), addresses precipitation evaluation and future projections in historical and scenario simulations downscaled from global climate model simulations. Since some of the simulations are still ongoing, only a subset of simulations (12 simulations) is used in Pichelli et al. (2021) depending on their completeness at the time of preparing the manuscript.

The structure of this manuscript is as follows: Sect. 2 presents the data and methodology of this study, Sect. 3 presents results on the evaluation of precipitation, and Sect. 4 provides a summary and conclusion.

2 Data and methods

2.1 Model simulations

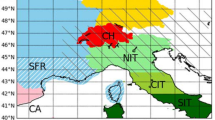

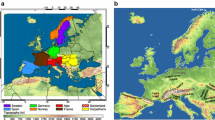

In this study, we investigate an ensemble of simulations conducted within a WCRP-sponsored CORDEX-FPS on convection over Europe and the Mediterranean (Coppola et al. 2020). The high-resolution kilometer-scale (2.2–4 km) and coarse resolution (12–25 km) simulations are provided and analysed on the greater Alpine region shown in Fig. 1. A total of 23 simulations (22 for coarse resolution simulations), performed by 22 European research groups are analysed. Six different regional climate models (RCMs) are represented in the ensemble—WRF (the Weather Research and Forecasting modeling system, Powers et al. 2017), RegCM4 (regional climate modeling system, Giorgi et al. 2012), AROME (Fumière et al. 2019; Belušić et al. 2020), REMO (regional climate model, Pietikäinen et al. 2018), UM (Unified model, Berthou et al. 2018; Chan et al. 2019), and COSMO (Consortium for Small Scale Modeling) in climate mode (Rockel et al. 2008; Baldauf et al. 2011).

The main difference between the coarse and high-resolution resolution simulation, in addition to the grid spacing, is the use of deep convection parametrization in coarse resolution models. In high-resolution models, the parameterization of deep convection is switched off, and thus convective processes are explicitly resolved.

The overarching goal is to assess the performance of a multi-model ensemble under present-day climate conditions. Thus, all groups have downscaled ERA-Interim reanalysis (Dee et al. 2011) for a ten-year long period (2000–2009) and have provided output data on the required greater Alpine domain. The majority of groups employed a double nest approach in which high-resolution model is nested into coarser resolution model output. In most of the cases, domain of the intermediate nest covers the EURO-CORDEX domain (Kotlarski et al. 2014; Jacob et al. 2014) although some variations exist. Furthermore, within this ensemble, we have a number of variations which allow for more nuanced investigations in future studies. The experimental setup includes (1) a multi-physics ensemble using WRF with a systematic exploration of cloud microphysics, shallow convection and planetary boundary layer processes parameterizations and (2) a sensitivity test on the nesting strategy using COSMO-CLM, where different intermediate resolution nests were considered, including a direct nesting into ERA-Interim. Also, pan-European kilometer-scale simulations are available for COSMO-CLM and UM. A detailed list of model versions and contributing groups is provided in Table 1. Here we only provide short descriptions of the different models.

WRF Nine simulations in this study were conducted with the WRF model, version 3.8.1, using the Advanced Research dynamical core (Skamarock 2008), which integrates the fully compressible, Euler non-hydrostatic equations cast in flux form, leading to the conservation of scalar variables. Equations are solved numerically on an Arakawa-C staggered grid. The model uses a vertical terrain-following, dry-hydrostatic pressure coordinate, with the top of the model at a constant pressure surface (20 hPa in this work). WRF can be applied over wide range of spatial and temporal scales, and includes a comprehensive selection of physical parameterization schemes for processes unresolved by the model dynamics. These simulations make up “CORDEX WRF coordinated experiment B”, as indicated by the second to last letter in the model names in Table 1. Each of the 9 WRF simulations in this study uses a different parametrization setting, identified by the last model name letter (B, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, L) in Table 1. Note that this final letter is unrelated to the lettering scheme in experiment A (Coppola et al. 2020) or in EURO-CORDEX (García-Díez et al. 2015; Katragkou et al. 2015). The ensemble is designed so that each WRF configuration differs in a single physics choice from other ensemble member. This enables the identification of the process responsible for the observed differences in the results (García-Díez et al. 2015). For the boundary layer turbulence, the schemes vary between the local closure MYNN2 (Nakanishi and Niino 2009; D, E, H, I, J) and the non-local YSU (Hong and Dudhia 2006; B, F, G, L). Soil processes are represented either by the NOAH LSM (Chen and Dudhia 2001; B, L) used in EURO-CORDEX or the state-of-the-art NOAH-MP (Niu et al. 2011; D, E, F, G, H, I, J), which includes a more sophisticated treatment of the soil and multi-layer snow processes. For shallow cumulus convection, the Global/Regional Integrated Model System (GRIMS; Hong and Coauthors 2013; B, D, F, G, H, I, L) or University of Washington (UW) scheme (Park and Bretherton 2009; E, J) was used. Unlike WRF EURO-CORDEX configurations, we used double-moment 6-class cloud microphysics schemes including graupel and other ice microphysics species which can develop in the resolved convective updrafts. The schemes included in the ensemble are WDM6 (Lim and Hong 2010; G, H, I, J) and Thompson and Eidhammer (2014), which has the option to consider the effect of natural and anthropogenic aerosols as condensation nuclei (B, D, E, L) or not (F). A common setting was used for all WRF simulations for shortwave and longwave radiative processes—RRTMG scheme (Iacono et al. 2008)—and for deep convective processes in the intermediate 15 km nest used to reach the 3 km convection-resolving grid spacing—Grell and Freitas (2014) scale- and aerosol-aware scheme. The intermediate nest covers the EURO-CORDEX domain at \(0.1375^\circ \) (\(\sim \)15 km) horizontal grid spacing to use a 5:1 odd nesting ratio to the standard convection-resolving domain with grid spacing of \(0.0275^\circ \) (\(\sim \)3 km). This enables an exact conservation of the fluxes in the one-way, two-step telescopic nesting used at each model time step. No nudging to ERA-Interim driven data has been used in any simulation.

RegCM4 The RegCM4 version (Giorgi et al. 2012) used in this study for two simulations has been extended to describe high resolution topography by adding a new non-hydrostatic dynamical option following the same equations as described in Dudhia (1993) and implemented in the Mesoscale Model MM5 (Grell et al. 1994). The model equations with complete Coriolis force option and a top radiative boundary condition as described in Grell et al. (1994) have been implemented in the RegCM4 code, with some modifications to achieve increased long term stability of the overall dynamics. The same physical packages available for the hydrostatic dynamical core RegCM4 (see (Giorgi et al. 2012)) have been adapted to use the different prognostic variables, while the Nogherotto–Tompkins (Nogherotto et al. 2016) and WSM5 (Hong et al. 2004) microphysics schemes options have been added. The Nogherotto–Tompkins Scheme for the stratiform cloud microphysics and precipitation is built upon the European Centre for Medium Weather Forecast’s Integrated Forecast System (IFS) (Tiedtke 1993; Tompkins 2007; Nogherotto et al. 2016). The scheme implicitly solves five prognostic equations for water vapour, cloud liquid water, rain, ice and snow. The Single-Moment 5-class microphysics scheme (WSM5) belonging to the WRF model (Skamarock 2008) has been also implemented in RegCM4. This scheme follows Hong et al. (2004) and treats vapour, rain, snow, cloud ice, and cloud water hydrometers separately. The scheme also treats ice and water saturation processes separately. It assumes water hydrometeors for temperatures above freezing, and cloud ice and snow when below the freezing level (Dudhia 1989; Hong et al. 1998). It accounts for supercooled water and a gradual melting of snow below the melting layer (Hong et al. 2004; Hong and Lim 2006).

The RegCM4 model is used for two simulations used in this analysis. These are ICTP and DHMZ, which at higher resolution differ in horizontal grid spacing (3 km and 4 km, respectively), the use of shallow convection scheme (used for ICTP, not for DHMZ), and in the driving data. At coarser resolution, i.e., for simulations at 12 km horizontal grid spacing they differ in the schemes used for the paramterization of PBL, large scale clouds, and convection. DHMZ at 12 km grid spacing is using WSM5 (see above) parameterization of large-scale clouds, Holtslag (non-local K-profile scheme) parameterization for PBL and Grell scheme for convection parameterization, while ICTP is using SUBEX (Subgrid Explicit Moisture Scheme based on RH and with only cloud water prognostic equation) for large-scale clouds, local 1.5 order parameterization of PBL after University of Washington scheme, and Tiedtke parameterization of deep convection.

AROME The climate version of AROME based on the weather prediction model AROME is used for three simulations conducted in this study. First examples of AROME employed in climate mode can be found in Déqué et al. (2016), Lind et al. (2016), Fumière et al. (2019), Coppola et al. (2020), Belušić et al. (2020) and Caillaud et al. (2021). AROME is a small-scale, non-hydrostatic, limited-area, atmospheric model. The dynamical core is the non-hydrostatic ALADIN spectral core with a semi-Lagrangian advection and a semi-implicit scheme (Bénard et al. 2010). The physical parametrizations of the model come mostly from the Méso-NH research model (Lafore et al. 1998; Lac et al. 2018). The microphysics scheme is ICE3, one-moment prognostic scheme with five prognostic variables of water condensates (cloud droplets, rain, ice crystals, snow and graupel) (Pinty and Jabouille 1998; Lascaux et al. 2006). Shallow convection is parameterized by the PMMC09 scheme based on the eddy diffusivity mass flux (EDMF) approach (Soares et al. 2004) associated to a statistical cloud scheme (Bechtold et al. 1995; Pergaud et al. 2009). The radiation parameterizations are versions of those from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) (RRTMG 16 bands for longwave (Iacono et al. 2008; Mlawer et al. 1997) and FMR 6 bands for shortwave (Fouquart and Bonnel 1980; Morcrette 2001)). The land surface modelling system is the SURFEX platform (Masson et al. 2013) and the urban scheme TEB (Masson 2000) is activated. Two versions of AROME are used in this study : HCLIM38-AROME and CNRM-AROME41. The main differences are: the model version (cycle 38 for HCLIM38-AROME and 41 for CNRM-AROME41 (Termonia et al. 2018)), different versions of SURFEX (7.3 for CNRM-AROME41 and 8 for HCLIM38-AROME), FLAKE inland waters activated in HCLIM38-AROME and aerosol forcing (Tegen et al. (1997) for HCLIM38-AROME and Nabat et al. (2013) for CNRM-AROME41). In addition, the three simulations conducted by the AROME model use different models for intermediate step—ALADIN for simulations conducted by CNRM (CNRM-ALADIN62, Nabat et al. 2020) and HCLIMcom and RACMO for simulations conducted by KNMI (see Table 1).

REMO One simulation is conducted by non-hydrostatic version of REMO model which is developed at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany and currently maintained at the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS) in Hamburg. This model is based on the latest hydrostatic REMO version, but further developed based on Laprise (1992) and Janjic et al. (2001). The model solves governing equations on a spherical Arakawa-C grid (Arakawa and Lamb 1977) in rotated coordinates and hybrid sigma-pressure coordinate. Model dynamics includes second order horizontal and vertical finite differences, leap-frog time stepping with semi-implicit correction and Asselin-filter, and fourth-order linear horizontal diffusion of momentum, temperature and water content. The prognostic variables in REMO are horizontal wind components, surface pressure, air temperature, specific humidity, cloud liquid water and ice. The physical packages originate from the global circulation model ECHAM4 (Roeckner et al. 1996), although many updates have been introduced (Pietikäinen et al. 2018)

UM The Unified Model (UM) was used for one simulation in this study. In particular, the configuration used here is based on the UKV Met Office operational model at UM version 10.1. The simulation spans a pan-European domain at 2.2 km grid spacing, and is driven at its lateral boundaries by ERA-Interim reanalysis for a 15 year period (1999–2014). No intermediate nest is used, and a spin-up region around the edge of the 2.2 km domain is excluded from the analysis to remove any boundary artefacts. Details of the model configuration can be found in Berthou et al. (2020), with a brief summary below. The 2.2 km model configuration uses the semi-implicit semi-Lagrangian ENDGame (Even Newer Dynamics for General atmospheric modelling of the environment, Wood et al. 2014) dynamical core. This solves the non-hydrostatic, fully-compressible deep-atmosphere equations of motion. The new dynamical formulation leads to improved numerical accuracy and stability (Walters et al. 2017). The 2.2 km model includes a two-stream radiation scheme (Edwards and Slingo 1996) and an extensive set of parameterizations describing the land surface (Best et al. 2011), boundary layer (Lock et al. (2000), with revisions described in Boutle et al. (2014)) with 3-dimensional Smagorinsky (1963) turbulent mixing, and mixed-phase cloud microphysics (based on Wilson and Ballard (1999), but with extensive modifications). The latter includes prognostic rain, which allows the three-dimensional advection of rain mass mixing ratio. This improves precipitation distributions in the vicinity of mountains, especially at the smaller grid spacing used in convection-permitting configurations (Lean et al. 2008; Lean and Browning 2013). Due to sub-grid inhomogeneity, clouds will form before the overall grid-box reaches saturation, and this is still true for kilometre-scale grid boxes (Boutle et al. 2016). The 2.2 km model uses the Smith (1990) cloud scheme to determine the fraction of the grid-box that is covered by cloud, and the amount and phase of condensed water in these clouds. The microphysics scheme then determines whether any precipitation has formed. The convection scheme is switched off entirely in the 2.2 km model, with all precipitation coming from the resolved dynamics. Even though this convection-permitting simulation was nested directly into ERA-Interim, an additional simulation over the same pan-European domain at 12 km resolution (Berthou et al. 2020) was considered in this study for the sake of comparison.

COSMO The climate version COSMO-CLM of the state-of-the-art weather prediction model COSMO (Consortium for Small Scale Modeling) is used for seven simulations conducted in this study (Rockel et al. 2008). It is a non-hydrostatic, limited-area, atmospheric model designed for applications for the meso-\(\beta \) to the meso-\(\gamma \) scales (Steppeler et al. 2003). The model describes compressible flow in a moist atmosphere, thereby relying on the primitive thermo-dynamical equations. These equations are solved numerically on a three-dimensional Arakawa-C grid (Arakawa and Lamb 1977) based on rotated geographical coordinates and a generalized, terrain following height coordinate (Doms and Baldauf 2015). The model applies a Runge–Kutta time-stepping scheme (Wicker and Skamarock 2002). The parameterization of precipitation is based on a one-moment micro-physics scheme that includes five categories of hydrometeors—cloud, rainwater, snow, ice and graupel (Doms et al. 2011). The physical parameterizations include the radiative transfer scheme by Ritter and Geleyn (1992), the Tiedtke parameterization of convection Tiedtke (1989) for grid spacing above 10 km, modified Tiedtke parameterization of shallow convection Tiedtke (1989) for grid spacing around 3 km (not used in ETHZa), and a turbulent kinetic energy-based surface transfer and planetary boundary layer parameterization (Raschendorfer 2001). The lower boundary of COSMO-CLM is the soil-vegetation-atmosphere-transfer model TERRA-ML (Schrodin and Heise 2002). COSMO simulations differ in model version used for integration, domain size, grid spacing and nesting strategy. ETHZ group is using a version of COSMO that is capable of running on GPUs (Leutwyler et al. 2017), while for other simulations COSMO 5.0 version is used. More details on the nesting strategy and grid spacing can be found in Table 1.

2.2 Observations

To assess the fidelity of the ensemble we use several high-resolution observational precipitation datasets available over different regions. These are:

-

1.

EURO4M-APGD For brevity we refer to this data as APGD data. APGD is daily precipitation available on a 5 km grid over the Alpine region from 1971–2008. This dataset is based on daily rain gauge station data, and is presented in Isotta et al. (2014).

-

2.

RdisaggH. This is a gridded hourly precipitation dataset, available for a shorter period (2003–2010) and over the area of Switzerland with the horizontal grid spacing of 1 km (Wüest et al. 2010). It is generated using a combination of station data with radar-based disaggregation.

-

3.

COMEPHORE This is another hourly observational dataset on a 1 km grid with coverage over metropolitan France (Tabary et al. 2012; Fumière et al. 2020). This product is also a combination of rain gauges and radar.

-

4.

GRIPHO GRIPHO is an hourly gridded precipitation dataset, available over Italy on a horizontal grid of 3 km (Fantini 2019). This data set is based on rain gauge measurements and is available for the period 2001–2016.

When dealing with the observations of precipitation, one must take into consideration shortcomings associated with these types of datasets. These include underestimation of precipitation, especially over mountainous regions due to the sparseness of stations at high elevations and mask effect problem in areas with high altitude for radar data, the systematic wind-induced rain gauge under-catch, and wetting and evaporation losses (see e.g., Sevruk 1985; Frei et al. 2003). Additionally, gridded datasets are typically produced using interpolation methods, which systematically induce underestimation of high intensities (smoothing effect) and overestimation of low intensities (moist extension into dry areas) (Isotta et al. 2014). Lastly, high elevation rain gauge stations are mostly located in valleys, therefore mountain slopes and mountain top estimates are more uncertain. Recent studies actually report that total annual rain and snowfall can be better represented by well-configured high-resolution atmospheric models in mountain terrain, than with spatial estimates derived from in-situ observational networks of precipitation gauges, and radar or satellite-derived estimates (Lundquist et al. 2020). The underestimation of precipitation due to the rain gauge undercatch, only, can be in the order of 4–50\(\%\) depending on the season, region and precipitation intensity (see e.g., Frei et al. 2003). To account for these uncertainties, we consider precipitation biases in the range between − 5 and + 25 as an acceptable range in some of our analyses. This range accounts for the mean rain gauge undercatch of up to 20\(\%\), but neglects seasonal, site and precipitation intensity variations of the observational error (see also Kotlarski et al. 2014).

For the analyses in this report, we take the observational periods that overlap with the targeted simulation period (2000–2009). This is 2000–2008 for the APGD data, 2003–2010 for the RdisaggH data, 2001–2009 for the GRIPHO data, and 2000–2009 for the COMEPHORE data. Although the periods completely overlap in some cases, for some the observational periods are shorter by 1–3 years. This shortfall is especially pronounced for hourly precipitation observations. For these reasons and those in previous paragraph, we do not expect a perfect match between the observations and model data. Instead, we look to see if the salient characteristics of precipitation are represented (e.g., whether or not the model ensemble fall within the observations spread).

2.3 Analysis

We present the analysis for indices listed in Table 2. The indices are calculated as seasonal values where the summer season includes June–July–August, winter December–January–February, spring March–April–May, and autumn September–October–November. These seasonal indices are calculated over the full 10-year simulation period.

For the evaluation of precipitation indices we employ following metrics:

-

Relative bias—the relative difference (\(\frac{model-observations}{observations}\)) of spatially averaged values for a selected region.

-

Spatial variability—ratio (\(\frac{model}{observations}\)) of spatial standard deviations of seasonal values across all grid points of a selected region.

-

Spatial correlation—the spatial correlation of seasonal values between model and observations across all grid points of a selected region.

To make the results comparable, all high-resolution RCM simulations are remapped before the analysis to a common grid with a grid spacing of 3 km using conservative remapping. The intermediate step i.e. coarser-resolution driving regional climate simulations have also been interpolated to the EURO-CORDEX 0.11\(^{\circ }\) grid (\(\sim \)12 km) using the same method. Observational data are kept at their original resolution to keep as detailed a representation as possible and where possible. However, for some of the evaluation metrics, like spatial correlation and spatial variability, which require a grid-cell-by-grid-cell comparison between model and observations, the observational data is remapped to match both 3 km and 12 km grid.

Due to the large amount of data produced by these kilometer-scale simulations, the analysis and the calculation of the indices is performed by each group individually using scripts provided by the corresponding author. Only the final results have been shared. This is the first time that this approach has been used but might become a standard in the future as it becomes increasingly difficult to cope with the data avalanches from kilometer-scale climate simulations (Schär et al. 2020).

3 Results

In this section we start with a short description of results presented in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, and then continue with a discussion of more specific aspects of the representation of precipitation by the ensemble of simulations.

3.1 A short description of figures

Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 provide an overview of spatial distribution of daily and hourly precipitation indices in observations and models. The ensemble mean of 3 km and 12 km RCM simulations are shown in Figs. 2 and 4 for daily and hourly precipitation, respectively, while Figs. 3 and 5 show results for each of the model simulation at 3 km and 12 km RCM grid spacing for heavy daily and hourly precipitation defined as 99th and 99.9th percentile, respectively, in summer season. These figures focus on the winter and the summer seasons, which represent two different synoptic situations—large-scale precipitation from mid-latitude storms in winter and more isolated, convective precipitation in summer.

Ensemble mean of analysed indices (from left to right: mean precipitation, precipitation frequency, precipitation intensity, and heavy precipitation defined as 99th percentile) calculated for daily precipitation in the winter and summer season. The results are obtained from EURO4M-APGD observations (Obs; Isotta et al. (2014)), 3 km-RCM (as a mean across 23 simulations) and 12 km-RCM model simulations (as a mean across 22 simulations)

Heavy daily summer precipitation defined as the 99th percentile over the Alpine region obtained from EURO4M-APGD observations (Obs; Isotta et al. (2014)) and different 3 km-RCM (red polygon) and 12 km-RCM (blue polygon) models run by different groups. The first panel on the left-hand side shows heavy precipitation calculated from observations. The first panel in red (blue) polygon shows a mean across different groups/models for high-resolution 3 km-RCM (12km RCM) simulations. Other panels show simulation from different groups/models

Heavy hourly summer precipitation defined as the 99.9th percentile obtained from RdisagH, COMEPHORE and GRIPHO observations (Obs) and different 3 km-RCM (red polygon) and 12 km-RCM (blue polygon) models run by different groups. The first panel on the left-hand side shows heavy precipitation calculated from observations. The first panel in red (blue) polygon shows a mean across different groups/models for high-resolution 3 km-RCM (12 km RCM) simulations. Other panels show simulation from different groups/models

Figures 6 and 7 provide a summary of regionally averaged biases for all daily and hourly indices (Table 2) and for all seasons. Figure 6 shows relative biases obtained from the 12 km and 3 km simulations when compared to the APGD data over Alpine region for daily precipitation indices. Figure 7 shows similar results but for hourly precipitation indices evaluated across the three regions (Switzerland, Italy, and France) where hourly precipitation observations are available. For both daily and hourly precipitation, the acceptable bias is indicated with white color and ranges between \(-5\%\) and \(+25\%\). In such a way, it takes into account the uncertainties associated with observations (see Sect. 2.2).

The relative bias of daily precipitation in four seasons (winter, spring, summer, and autumn). Bias is calculated for each of the indices with regard to the APGD observations over the area of APGD observations. Each box represents domain mean bias for 3 km (top triangle), and corresponding (driving) 12 km (bottom triangle) simulation. White color indicates an acceptable bias range which accounts for the uncertainties in the observations due to the systematic rain gauge under-catch \((\sim 20\%)\)

As Fig. 6, but for hourly precipitation and for the three regions (Switzerland, France, and Italy) where hourly precipitation observations are available

Box-plots of (red) 3 km and (blue) 12 km model biases for indices presented in Table 2 for (upper row) daily and (bottom row) hourly precipitation over the three regions—Switzerland, France, and Italy—and for all seasons. The grey shading indicates acceptable uncertainty range (0–25\(\%\)) of observations due to the systematic rain gauge under-catch which amounts to around 20\(\%\). For daily precipitation, relative differences between two observational data sets (APGD and available high-resolution data) for all indices are shown as yellow dots. These differences are calculated across overlapping regions

The uncertainties in model simulations are presented in Fig. 8 using box plots for both daily and hourly precipitation over three different regions. The results show the spread of relative bias for different indices in all seasons and for the three regions. As a reference data for both daily and hourly precipitation, we use hourly observations across the three regions which are summed up to daily precipitation values. In addition to relative models biases, for daily precipitation we also show differences between observational datasets i.e. relative difference between APGD data and higher resolution observations RdisaggH, COMEPHORE and GRIPHO over Switzerland, France and Italy, respectively. It is important to note that in some cases, for example heavy daily precipitation, these differences between the two observations can be larger than 20\(\%\).

To assess the performance of models in representing spatial characteristics of precipitation, we use Taylor diagrams to combine the results of spatial correlation coefficient and spatial variability for daily (Fig. 9) and hourly precipitation (Fig. 10). For daily precipitation we show results for mean precipitation only, since for other indices the conclusion does not differ between daily and hourly precipitation.

Spatial Taylor diagrams exploring the multi-model mean performance with respect to the spatial variability of mean seasonal daily precipitation over the three regions—Switzerland, France, and Italy. The diagrams combine the spatial correlation (cos(azimuth angle)) and the ratio of spatial variability (radius). Red circles indicate results obtained from a 3-km multi-model mean, while blue circles indicate results obtained from a 12-km multi-models mean

Spatial Taylor diagrams exploring the multi-model mean performance with respect to the spatial variability of seasonal hourly precipitation. The performance is explored for hourly precipitation (first column) frequency, (middle column) intensity and (last column) heavy hourly precipitation defined as 99.9th percentile over the three regions—Switzerland, France, and Italy. The diagrams combine the spatial correlation (cos(azimuth angle)) and the ratio of spatial variability (radius). Red circles indicate results obtained from a 3-km multi-model mean, while blue circles indicate results obtained from a 12-km multi-models mean

Diurnal cycle of mean precipitation, wet-hour frequency and heavy precipitation defined as 99th percentile for each hour averaged over Switzerland (leftmost panels), France (middle panels) and Italy (rightmost panels). Black line denotes the observations from Wüest et al. (2010) for Switzerland, Fumière et al. (2020) for France and Fantini (2019) for Italy. Thick red and blue lines denote the ensemble mean of the high-resolution 3 km RCM simulation and coarse-resolution 12 km RCM simulation, respectively. Thin red and blue lines denote individual model realizations in the right column of each section

The last figure, Fig. 11 presents the results for diurnal cycles of mean precipitation, wet-hour frequency, and the 99th percentile of precipitation. The results are obtained for three regions where hourly precipitation is available—Switzerland, Italy and France. Both the ensemble mean (left panels) and the individual ensemble members (right panels) are shown, along with the corresponding indices obtained from the observations.

3.2 How well do kilometer-scale climate models represent spatial patterns and spatial variability of precipitation?

Both summer and winter seasons are characterized by higher precipitation in regions of high orography. However, the differences between mountainous areas and surrounding lowlands are smaller in winter than in summer (Fig. 2) in accordance with the increase of cyclone activity at the lee of the Alps mountains in the Genoa Gulf (Trigo et al. 1999). As it can be seen in Fig. 2, both, the ensemble mean of 3 km and 12 km RCMs capture these spatial patterns of mean daily precipitation, intensity, frequency and heavy precipitation quite well for both summer and winter. However some biases like overestimation of precipitation frequency in winter and summer, and underestimation of precipitation intensity and heavy precipitation in summer are present for 12 km model ensemble. Some of these biases, like overestimation of frequency in winter, exist in 3 km model ensemble, and are most likely inherited from the coarse resolution model as it can be seen that they overestimate the frequency even more in both winter and summer season. It can also be seen that 3 km model ensemble reproduces the intensity and heavy precipitation much better than the 12 km model ensemble. These differences between the models are furthermore pronounced for hourly precipitation shown in Fig. 4. Here the 12 km model ensemble largely overestimates wet-hour frequency, especially over topography, while intensity is underestimated. This combination leads to a relatively good performance in simulating mean daily precipitation as seen in Fig. 2, but it is clear that this is for the wrong reasons. On the other side, the 3 km model ensemble performs much better, reduces the overestimation in wet-hour frequency and reduces the underestimation of hourly precipitation intensity. However, it tends to overestimate hourly precipitation intensity and underestimate heavy hourly precipitation over Italy and France.

Figures 3 and 5 show how different models of the 3 km and 12 km ensembles perform in simulating heavy daily (defined as the 99th percentile) and hourly (defined as the 99.9th percentile) precipitation in the summer season. In both cases, high-resolution simulations tend to produce more intense precipitation than their driving coarse resolution models. This is especially pronounced for heavy hourly precipitation. The difference between the two largest groups of model simulations, WRF and CCLM, also becomes visible. CCLM simulations from all groups produce more intense heavy precipitation than WRF simulations. This is especially true for heavy hourly precipitation, and to a lesser extent for heavy daily precipitation. We should also note that there are a few WRF model configurations (IPSL, BCCR and, to a lesser extent, CICERO) that substantially underestimate heavy precipitation (Fig. 3) in the summer season. The underestimation is found for both high-resolution and coarse resolution models, and is found for the summer season only. In other seasons these models show very similar results to the others. This indicates that these model configurations have problems in initiating small scale convective summer precipitation over orography but perform well when large-scale forcing plays a dominant role as for winter precipitation. On the other side, the most intense heavy precipitation at 3 km and 12 km is produced by RegCM model simulations conducted by DHMZ. Here we can also note that differences between WRF and RegCM model configurations (which differ in model physics) can be larger than differences between two different models. Furthermore, CCLM simulations that use different nesting strategies do not show any substantial differences.

The spatial representation of daily and hourly precipitation is further assessed using Taylor diagrams which combine the spatial correlation and the ratio of spatial variability (Figs. 9, 10) for the three different regions. For most of the regions and indices, spatial correlation coefficients are above 0.5. The largest spatial correlation of 0.9 is found for wet-hour frequency in summer across Italy for both 3 km and 12 km ensemble mean. However, frequency is one of the indices where spatial correlation coefficients vary the most between the seasons and regions and between the models. For other indices like mean daily precipitation, hourly precipitation intensity and heavy hourly precipitation, there is no big difference in spatial correlation coefficients between the two model ensemble means. However, the ratio of spatial variability shows a larger difference between the two model ensembles. Figure 10 shows that 12 km ensemble mean underestimates the spatial variability of precipitation intensity and heavy hourly precipitation in all regions and all seasons, and overestimates the spatial variability of wet-hour frequency. This is consistent with substantial underestimation of precipitation intensity and overestimation of frequency shown in Fig. 4. On the other side, the 3 km model ensemble mean produces ratio of spatial variability of precipitation intensity and heavy hourly precipitation much closer to 1, i.e., much closer to observed spatial variability but it also overestimates the spatial variability by up to \(\sim \)30% over France and Italy. This overestimation is not necessarily a sign of a bad model performance, since a part of these differences can be explained by observational uncertainties due to the sparse observational networks over higher altitudes that receive more precipitation and interpolation methods used to produce gridded data sets (see Sect. 2.2).

Overall, we can say that the higher-resolution model ensemble produces more realistic precipitation patterns and variability than the coarser resolution model ensemble.

3.3 How well do kilometer-scale climate models represent spatial/areal means?

Next we analyse spatial means of relative biases presented in Figs. 6, 7 and 8. Model biases in terms of daily precipitation and indices over the area of APGD observations are presented in Fig. 6. For the Alpine region in the winter and spring season, relative biases are quite small, i.e., they are in the acceptable range which accounts for observational uncertainties. Most of the models overestimate mean precipitation and precipitation frequency, which is most pronounced for the GERICS simulation conducted by the REMO model and DHMZ simulation conducted by the RegCM model. In addition, coarse-resolution models tend to underestimate precipitation intensity and heavy precipitation. However, this underestimation is not visible in high-resolution models (with the exceptions of a few WRF simulations). On the other side, the ensemble mean and almost all models tend to underestimate precipitation in the summer and autumn season (Fig. 6). This underestimation is more pronounced for almost all WRF simulations, especially for IPSL, BCCR and CICERO as also seen in Fig. 3. The IPSL, BCCR and CICERO simulations produce too little precipitation in all but the winter season. This systematic seasonal sign reversal in the biases is less pronounced for the CCLM simulations. Almost all simulations consistently perform better for the wet-day intensity and heavy daily precipitation intensity over the seasons at a higher resolution. The DHMZ simulation conducted by RegCM tends to overestimate the precipitation throughout the entire year. It can be seen that in all cases the higher resolution model produces more intense precipitation which is consistent with all other simulations. However, this model configuration, the same as REMO conducted by GERICS produces more frequent precipitation at a higher resolution than the coarse resolution model, which is opposite to other simulations where higher resolution models produce less frequent precipitation than their driving coarse-resolution models.

Next we turn our attention to biases in hourly precipitation presented in Fig. 7 and calculated over the area of Switzerland, France and Italy. For Switzerland, all simulations produce too frequent and too light hourly precipitation in almost all seasons except for summer. It can be seen that even in these seasons, the higher resolution model tends to perform better by reducing the wet-hour frequency and producing more intense precipitation. In summer, only the 12 km RCMs show an overestimation of wet-hour frequency and an underestimation of intensity, while in the 3 km-RCMs the wet-hour frequency tends to be underestimated, but precipitation intensity and heavy precipitation are captured quite well. The exceptions are GERICS and the aforementioned IPSL, CICERO and BCCR simulations which largely overestimate and underestimate wet-hour frequency in summer, respectively. All high-resolution simulations perform well and/or better than coarse resolution models for the heavy hourly precipitation in spring, summer and autumn seasons, with the exceptions of ETHZa which shows a wet bias for the heavy hourly summer precipitation (Fig. 7). We can also note that despite a large overestimation of wet-hour frequency and overestimation of daily precipitation, the DHMZ simulations have very small biases for precipitation intensity and heavy precipitation at the hourly time scale over Switzerland.

Similarly, for France, the hourly precipitation occurs too frequently with too weak intensity in winter and spring for most models (Fig. 7, second column). These biases are smaller for high-resolution models. In summer (and to a lesser degree in autumn), most of the high-resolution models show an underestimation of wet-hour frequency (with the exception of DHMZ), while coarse resolution models still tend to overestimate the wet-hour frequency (with the exception of the CCLM simulations). However, summer (and autumn) precipitation intensity and heavy precipitation are much better captured, especially with high-resolution models.

In contrast, an underestimation of wet-hour frequency prevails in all seasons over Italy with the exception of the GERICS simulation (Fig. 7, third column). Over Italy, the biases are more pronounced in summer season for all indices, where 12 km RCMs underestimate the intensity and heavy precipitation. However, these biases are smaller or even positive in high-resolution models (especially for precipitation intensity). The same as in other regions, WRF simulations conducted by IPSL, BCCR and CICERO show large underestimation of all precipitation indices in the summer season.

Overall, high-resolution models tend to produce less frequent but more intense precipitation than their driving models, and this feature is visible in ensemble mean and across all models.

The above biases are further summarized in Box plots shown in Fig. 8 for both daily and hourly precipitation. For daily precipitation, the difference between the high and coarse resolution simulations is not as large as for hourly precipitation, especially in the median. Also, both simulations are closer to observations for daily precipitation than for the hourly precipitation. For hourly precipitation, this is mostly true for high-resolution simulations only. Another important difference between the high and coarse resolution simulations emerges in Fig. 8. In all regions and for almost all indices, high-resolution simulations yield smaller uncertainty ranges. This is the most pronounced for wet-hour frequency in the summer season for all regions and heavy daily precipitation in all regions and all seasons. For example, on average across the three regions for wet-hour frequency in summer, coarse resolution models span a bias range from \(\sim \,-\) 50 to > 90%, i.e. an uncertainty range larger than 140%, while high-resolution simulations span around half of that uncertainty range (\(\sim \)80%). The uncertainty ranges are the largest for wet-hour frequency, and smaller for other indices, but as mentioned above, they are almost always smaller for high-resolution simulations.

Of course, these uncertainty ranges could be further reduced by selecting a subset of simulations as done in Herrera et al. (2010), and the potential users may decide which are good enough for their purpose. However in this work we want to transparently provide all simulations results, and to acknowledge all groups and their effort in running such demanding simulations. These results also underline the importance of model configuration and how some small differences in the setup could lead to large differences in model results.

3.4 How well do kilometer-scale climate models represent the diurnal cycle of summer precipitation?

In summer, the diurnal cycle in precipitation occurrence and intensity is quite distinct and is most pronounced for Switzerland (Fig. 11). This pattern is typical for the region in summertime when it rains heavily mostly in the late afternoon and early evening. The 3 km ensemble mean improves the representation of the diurnal cycle in all analyzed aspects. For mean precipitation, the timing is much better captured by the 3 km ensemble mean, even though the peak amount of mean precipitation is similar to the 12 km ensemble mean. However, when looking into the diurnal cycle of wet-hour frequency and heavy precipitation we see that this is for wrong reasons. The 12 km ensemble mean rains too often but with too weak intensity, which at the end results in reasonable mean precipitation. The peak of mean precipitation and wet-hour frequency is centered around 12 UTC, which indicates that convection parameterizations are triggered as soon as there is some small instability resulting in weak precipitation and thus preventing the development of larger instability and more intense precipitation. In reality, as seen from the observations, the build-up of convection takes longer and results in more intense precipitation in the afternoon. Another shortcoming of the 12 km ensemble mean is the inability to reproduce the diurnal cycle of heavy precipitation. This is most pronounced over Switzerland where the 12 km ensemble mean shows almost a flat line.

However, it should be noted that despite the impressive performance of the 3 km ensemble mean, there is still quite a large spread amongst the ensemble members (the same as for 12 km ensemble members) as it can be seen in the spaghetti plots in Fig. 11. In addition, some ensemble members produce systematic biases. For example, 12 km ensemble simulations systematically overestimate the wet-hour frequency and underestimate heavy precipitation throughout the day for all regions while all 3 km ensemble simulations underestimate wet-hour frequency over France.

3.5 How different are kilometer-scale climate models from their driving coarse-resolution climate models?

The overall improvement of the spatial distribution of summer daily heavy precipitation in the convection-resolving simulations can be seen in Fig. 3. This qualitative comparison is complemented by examining the relative biases with respect to the APGD observations for all daily indices and for all seasons (Fig. 6). In summer, the main improvements occur in precipitation intensity and in extreme precipitation (see also Fig. 2) where on average, 3 km model ensemble produces \(\sim \)20% more intense precipitation than 12 km model ensemble. Improvements are also notable for these two indices during autumn where they are quite consistent across the different ensemble members. Conversely, daily mean precipitation and wet-day frequency often exhibit larger biases or reversals of sign in the high resolution simulations compared to the 12 km runs. Many ensemble members overestimate mean precipitation and wet-day frequency during winter and spring, with no clear systematic advantage of the convection-resolving scale over the 12 km for these indices. Conversely, the tendency during summer and fall seasons is towards an underestimation of precipitation with some ensemble members exhibiting biases over − 60% (See Conclusions for further discussion). Model-to-model differences are apparent. For example, the WRF model systematically underestimates warm half year precipitation (a situation that gets worse when moving from 12 to 3 km for wet-hour frequency) while GERICS and DHMZ exhibits worsening biases in the cold half year when moving from coarse to fine resolution.

At the hourly timescale, the qualitative improvement of the convection-resolving simulations in the precipitation intensity and spatial distribution is clearer than for the daily timescale (Figs. 4 and 5). This is mainly due to the poor performance of the parameterized-convection simulations. Quantitative bias estimates (Fig. 7) show that this is true for all seasons except for the winter season, when biases are stronger than at the daily time-scale, but still smaller for convection-permitting simulations. Results are highly region-dependent, though. The largest improvements occur over Switzerland, especially in spring and summer when 3 km biases are very low for precipitation intensity and extreme precipitation for many models. Furthermore, the differences between the two model ensembles is also the largest at hourly time scale than at daily time scale (see also Fig. 8). For example, 3 km model ensemble shows \(\sim \)40% more intense and \(\sim \)50% less frequent summer precipitation than 12 km model ensemble.

Model-to-model differences are also apparent at the hourly time-scale. WRF still shows dry biases, especially in the 12 km runs for precipitation intensity and extreme precipitation, which are improved (and often reversed to a wet bias) in the 3 km simulations. ICTP simulation conducted by RegCM4 shows the largest overturn of the bias when going from coarse to higher resolution. The 12 km ICTP simulation shows large overestimation of hourly precipitation frequency along the year. The largest is found for summer hourly frequency where it is above 100%, while in 3 km simulation this bias is reduced to \(\sim \) \(-\) 20%.

Note that the observational databases used for the different regions differ from each other in many aspects and suffer from well-known issues related to station density, radar masking and methodological limitations (see Sect. 2.2). Thus even the difference between the two observations can be large as seen in Fig. 8. Therefore, we cannot conclude unequivocally that all the regional differences and biases are due to different climatic conditions or the ability of the models to represent particular processes; they could also be due to the different reference observational databases used and their relative shortcomings.

4 Conclusions

This study presents the evaluation of precipitation in a new set of high-resolution climate simulations conducted within the ongoing CORDEX-FPS on convection. In total, we analyze 23 simulations with a horizontal grid spacing of around 3 km against high-resolution observational datasets and coarser resolution driving simulations (22 simulations available). In almost all cases, coarse-resolution simulations with grid spacings in the range 12–25 km serve as an intermediate nest and provide boundary data for the high-resolution models. The main difference between the coarse- and high-resolution simulations is the treatment of convection (i.e., thunderstorms and rain showers) in the model. It is assumed that, at a horizontal grid spacing larger than a few km, convection can not be represented by grid-scale processes and thus it is parameterized. Conversely, on km-scale grids, the grid spacing is small enough to allow explicit representation of convective processes and thus the parameterization of deep convection is switched off. Likewise, at the 3 km resolution, the dynamics is better resolved; in particular, the influence of orography on the flow. The simulations are driven by ERA-Interim reanalysis, and are integrated by six different RCMs over a 10-year long period. The model performance is assessed through several basic precipitation indices: mean daily precipitation, daily/hourly precipitation intensity and frequency, and heavy daily and hourly precipitation defined as the 99th and 99.9th percentile, respectively.

In general, the spatial patterns and spatial variability of precipitation are represented quite well by the ensemble mean of km-scale simulations on both daily and hourly time scales. In many cases, the representation by the 3 km ensemble mean is better than the ensemble mean of the coarse resolution simulations. This is especially true in the summer season when the coarse resolution model overestimates the frequency and underestimates the intensity of both daily and hourly precipitation. The superior performance of 3 km is the most pronounced for heavy precipitation events. On average, 3 km ensemble produces \(\sim \)40% more intense hourly precipitation intensity and \(\sim \)50% less frequent hourly precipitation in summer. Furthermore, the uncertainty ranges are reduced by almost half when using higher-resolution simulations. This is the most pronounced for summer wet-hour frequency and precipitation intensity at hourly timescales.

The diurnal cycles of summer mean precipitation, wet-hour frequency and heavy precipitation are analyzed over three different regions—Switzerland, France and Italy (Fig. 11). Over all three regions, the ensemble mean of km-scale simulations shows superior performance to the ensemble mean of coarse resolution simulations. It is clear that the longstanding problem of incorrect timing with too frequent and too weak precipitation is greatly improved by switching off the parameterization of convection. However, a large spread exists even within the km-scale ensemble and there are many deficiencies in these modeling system that need to be addressed in the future.

Many of these issues are on display in the daily and hourly biases of the individual ensemble members (Figs. 6 and 7). Detailed investigations of the differences between ensemble members is beyond the scope of this paper. But there are some initial thoughts on the issues presented in the previous section, in particular on the WRF ensemble members. The behaviour of this group of simulations is in contrast with the overall summer wet bias over the region in the WRF EURO-CORDEX configurations (Kotlarski et al. 2014), although those correspond to a different model version and physics schemes. While the exploration of the reasons behind the WRF summer dry bias is beyond the scope of this paper, and calls for a specific study, we may make some preliminary explanations. Given that all WRF members show summer dry bias, the contrasting results with EURO-CORDEX may be due to the common configuration used in all WRF ensemble members (e.g. the use of 2-moment cloud microphysics schemes). Also, the low variability across some WRF ensemble members seems to imply that model numerics and other common setup are in this case more important than the choice of physical parameterizations. This could be due to the absence of a deep convection parameterization, which has been previously identified as a major source of uncertainty in the simulation of summer precipitation (Jerez et al. 2013; Mooney et al. 2017). Irrespective of the final determination, however, the overall results emphasize the benefits of an ensemble-based approach at kilometer scales, as reliance on any one model or simulation may produce misleading results.

Although some differences and biases still persist in the convection-resolving simulations, this approach in an ensemble framework offers a promising way forward for improving climate simulations and our understanding of local to regional-scale climate and climate change. In particular, the improvements in spatial representation, frequency, and extremes of precipitation are pronounced compared to coarser resolution counterparts. Importantly the ensemble results presented here confirm many of the results presented by numerous previous studies over different domains and time periods (Ban et al. 2014; Kendon et al. 2014; Prein et al. 2015; Kendon et al. 2017; Berthou et al. 2018). This level of consistency across a large multi-model ensemble provides strong supporting evidence that these improvements are indeed robust.

As indicated earlier in the manuscript, some of the models are run for the first time at such a high-resolution and no prior calibration or tuning has been performed, as is the case for many coarse resolution models (e.g. GCMs and ESMs). Additionally, high-resolution simulations depend on the driving data. While these high-resolution models can improve climate features related to the increase of resolution and explicit representation of atmospheric dynamics like convection, some aspects like storm-tracks or fronts are inherited from the driving data. High-resolution simulations also need high-resolution observations for evaluation that are not easily accessible and come with their own shortcomings. For example, in areas of high/steep topography high-resolution models may well be more reliable than the observations (Lundquist et al. 2020). And last but not least, high-resolution simulations are still using parameterizations that are too simple to describe complex processes or parameterizations that are too expensive to be executed every time step (for example radiation scheme which is executed every 15-20 minutes) or parameterizations that were designed for coarser resolutions, and the assumptions associated with them may not hold at km-scales. For some of the models, more complex and advanced schemes might exist, however, they are not used often due to the added computational cost. An example of it is a two-moment micro-physics scheme available in COSMO, but not used in simulations presented here since it would result in increasing the computational cost of decade-long simulations. Other examples include soil models, surface-atmosphere exchange, snow models, etc.

There is a need for better understanding the reasons for the improved representation of precipitation at higher resolution (better representation of topography versus switching of parametrization of convection) (see e.g., Langhans et al. 2013; Vergara-Temprado et al. 2020), to understand what features of the parameterisations are performing well, and which process aspects of convection are not well represented by the parameterisations that are better represented by an explicit simulation (see e.g., Meredith et al. 2015). This understanding could then contribute to a development of better parameterizations for 12 km models. There is also a pressing need for new approaches and improvements to remaining physical parameterization schemes (Palmer and Stevens 2019) as we move increasingly toward O(1km) with the ambition to enhance the reliability of our regional climate projections.

Despite these challenges, we believe that modelling on these scales is the future and that the improvements easily justify the costs. The largest gaps in our understanding of future change exist around how global warming plays out at regional scales. The most destructive impacts of this change are to be found in extreme events, mainly those related to precipitation. These are the phenomena that ensembles such as this one can reproduce with greater reliability and realism than their coarser predecessors. If the aim is to develop projections with reliable regional precision then these types of modeling activities and their development are invaluable.

References

Arakawa A, Lamb V (1977) Computational design of the basic dynamical processes in the UCLA general circulation model. In: Chang J (ed) Methods in computational physics: general circulation models of the atmosphere, vol 17. Academic Press, New York, pp 173–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-460817-7.50009-4

Baldauf M, Seifert A, Förstner J, Majewski D, Raschendorfer M, Reinhardt T (2011) Operational convection-scale numerical weather prediction with the COSMO model: description and sensitivities. Mon Weather Rev 139:3887–3905

Ban N, Schmidli J, Schär C (2014) Evaluation of the convection-resolving regional climate modeling approach in decade-long simulations. J Geophys Res Atmos 119:7889–7907. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JD021478

Bechtold P, Cuijpers J, Mascart P, Trouilhet P (1995) Modeling of trade wind cumuli with a low-order turbulence model: toward a unified description of Cu and Se clouds in meteorological models. J Atmos Sci 52(4):455–463

Belušić A, Prtenjak MT, Güttler I, Ban N, Leutwyler D, Schär C (2018) Near-surface wind variability over the broader adriatic region: insights from an ensemble of regional climate models. Clim Dyn 50(11):4455–4480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-017-3885-5

Belušić D, de Vries H, Dobler A, Landgren O, Lind P, Lindstedt D, Pedersen RA, Sánchez-Perrino JC, Toivonen E, van Ulft B, Wang F, Andrae U, Batrak Y, Kjellström E, Lenderink G, Nikulin G, Pietikäinen JP, Rodríguez-Camino E, Samuelsson P, van Meijgaard E, Wu M (2020) HCLIM38: A flexible regional climate model applicable for different climate zones from coarse to convection permitting scales. Geosci Model Dev 13:1311–1333. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-13-1311-2020

Bénard P, Vivoda J, Mašek J, Smolíková P, Yessad K, Smith C, Brožková R, Geleyn JF (2010) Dynamical kernel of the Aladin-NH spectral limited-area model: revised formulation and sensitivity experiments. Q J R Meteorol Soc 136(646):155–169

Berthou S, Kendon EJ, Chan SC, Ban N, Leutwyler D, Schär C, Fosser G (2018) Pan-European climate at convection-permitting scale: a model intercomparison study. Clim Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4114-6

Best M, Pryor M, Clark D, Rooney G, Essery R, Ménard C, Edwards J, Hendry M, Porson A, Gedney N et al (2011) The joint UK land environment simulator (JULES), model description-part 1: energy and water fluxes. Geosci Model Dev 4(3):677–699

Boutle I, Abel S, Hill P, Morcrette C (2014) Spatial variability of liquid cloud and rain: observations and microphysical effects. Q J R Meteorol Soc 140(679):583–594

Boutle I, Finnenkoetter A, Lock A, Wells H (2016) The London model: forecasting fog at 333 m resolution. Q J R Meteorol Soc 142(694):360–371

Brockhaus P, Lüthi D, Schär C (2008) Aspects of the diurnal cycle in a regional climate model. Meteorol Z 17:433–443

Caillaud C, Somot S, Alias A, Bernard-Bouissières I, Fumière Q, Laurantin O, Seity Y, Ducrocq V (2021) Modelling Mediterranean heavy precipitation events at climate scale: an object-oriented evaluation of the CNRM-AROME convection-permitting regional climate model. Clim Dyn 56:1717–1752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05558-y

Chan SC, Kendon EJ, Berthou S, Fosser G, Lewis E, Fowler HJ (2020) Europe-wide precipitation projections at convection permitting scale with the Unified Model. Clim Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-020-05192-8

Chen F, Dudhia J (2001) Coupling an advanced land surface-hydrology model with the Penn state-NCAR MM5 modeling system. Part I: model implementation and sensitivity. Mon Weather Rev 129:569–585

Christensen J, Carter T, Mea Rummukainen (2007) Evaluating the performance and utility of regional climate models: the PRUDENCE project. Clim Change 81:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-006-9211-6

Coppola E, Sobolowski S, Pichelli E, Raffaele F, Ahrens B, Anders I, Ban N, Bastin S, Belda M, Belusic D et al (2020) A first-of-its-kind multi-model convection permitting ensemble for investigating convective phenomena over Europe and the Mediterranean. Clim Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-018-4521-8

Dee DP, Uppala SM, Simmons AJ, Berrisford P, Poli P, Kobayashi S, Andrae U, Balmaseda MA, Balsamo G, Bauer P, Bechtold P, Beljaars ACM, van de Berg L, Bidlot J, Bormann N, Delsol C, Dragani R, Fuentes M, Geer AJ, Haimberger L, Healy SB, Hersbach H, H\(\acute{o}\)lm EV, Isaksen L, Kallberg P, Köhler M, Matricardi M, McNally AP, Monge-Sanz BM, Morcrette J, Park BK, Peubey C, de Rosnay P, Tavolato C, Th\(\acute{e}\)paut J, Vitart F (2011) The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q J R Meteor Soc 137(656):553–597

Doms G, Baldauf M (2015) A description of the non-hydrostatic regional COSMO-Model, part I: dynamics and numerics. DWD, Offenbach. http://cosmo-model.org/content/model/documentation/core/default.htm

Doms G, Förstner J, Heise E, Herzog HJ, Mironov D, Raschendorfe M et al (2011) A description of the non-hydrostatic regional COSMO-Model, part II: physical parameterization. DWD, Offenbach. http://cosmo-model.org/content/model/documentation/core/default.htm

Dudhia J (1989) Numerical study of convection observed during the winter monsoon experiment using a mesoscale two-dimensional model. J Atmos Sci 46:3077–3107

Dudhia J (1993) A nonhydrostatic version of the PENN state-NCAR mesoscale model: validation tests and simulation of an Atlantic cyclone and cold front. Mon Weather Rev 121:1493–1513

Déqué M, Alias A, Somot S, Nuissier O (2016) Climate change and extreme precipitation: the response by a convection-resolving model. Research activities in atmospheric and oceanic modelling CAS/JSC Working group on numerical experimentation Report No 46. http://www.wcrp-climate.org/WGNE/blue_book.html

Edwards JM, Slingo A (1996) Studies with a flexible new radiation code. I: Choosing a configuration for a large-scale model. Q J R Meteorol Soc 122(531):689–719. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49712253107

Fantini A (2019) Climate change impact on flood hazard over Italy. Ph.D. thesis, Universita degli Studi di Trieste. http://hdl.handle.net/11368/2940009

Fouquart Y, Bonnel B (1980) Computations of solar heating of the earth’s atmosphere—a new parameterization. Beitraege zur Phys der Atmos 53:35–62

Frei C, Christensen JH, Dèquè M, Jacob D, Jones RG, Vidale PL (2003) Daily precipitation statistics in regional climate models: evaluation and intercomparison for the European Alps. J Geophys Res 108:4124

Fumière Q, Déqué M, Nuissier O, Somot S, Alias A, Caillaud C, Laurantin O, Seity Y (2020) Extreme rainfall in Mediterranean France during the fall: added value of the CNRM-AROME convection-permitting regional climate model. Clim Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-019-04898-8

García-Díez M, Fernández J, Vautard R (2015) An RCM multi-physics ensemble over Europe: multi-variable evaluation to avoid error compensation. Clim Dyn 45(11–12):3141–3156

Giorgi F (2019) Thirty years of regional climate modeling: Where are we and where are we going next? J Geophys Res Atmos 124(11):5696–5723. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD030094. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2018JD030094

Giorgi F, Jones C, Asrar GR (2009) Addressing climate information needs at the regional level: the CORDEX framework. WMO Bull 58:175–183. https://public.wmo.int/en/bulletin/addressing-climate-information-needs-regional-level-cordex-framework

Giorgi F, Coppola E, Solmon F, Mariotti L, Sylla MB, Bi X, Elguindi1 N, Diro GT, Nair V, Giuliani G, Turuncoglu UU, Cozzini S, Güttler I, O’Brien TA, Tawfik AB, Shalaby A, Zakey AS, Steiner AL, Stordal F, Sloan LC, Brankovic C (2012) RegCM4: model description and preliminary tests over multiple CORDEX domains. Clim Res 52:7–29

Grell G, Dudhia J, Stauffer D (1994) Description of the fifth generation penn state/NCAR Mesoscale model (MM5). National Center for Atmospheric Research Tech Note NCAR/TN-398+STR. https://doi.org/10.5065/D60Z716B

Grell GA, Freitas SR (2014) A scale and aerosol aware stochastic convective parameterization forweather and air quality modeling. Atmos Chem Phys 14:5233–5250. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-5233-2014

Gutowski WJ, Giorgi F, Timbal B, Frigon A, Jacob D, Kang HS, Raghavan K, Lee B, Lennard C, Nikulin G, O’Rourke E, Rixen M, Solman S, Stephenson T, Tangang F (2016) WCRP COordinated Regional Downscaling EXperiment (CORDEX): a diagnostic MIP for CMIP6. Geosci Model Dev 9(11):4087–4095. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-4087-2016

Hentgen L, Ban N, Schär C (2019) Clouds in convection resolving climate simulations over Europe. J Geophys Res Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JD030150

Herrera S, Fita L, Fernández J, Gutiérrez JM (2010) Evaluation of the mean and extreme precipitation regimes from the ensembles regional climate multimodel simulations over Spain. J Geophys Res Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JD013936.https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2010JD013936

Hong SY et al (2013) The global/regional integrated model system (grims). J Atmos Sci 49:219–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13143-013-0023-0

Hong SY, Lim JOJ (2006) The WRF single-moment 6-class microphysics scheme (WSM6). J Korean Meteor Soc 42:129–151

Hong SY, Juang HMH, Zhao Q (1998) Implementation of prognostic cloud scheme for a regional spectral model. Mon Weather Rev 126:2621–2639

Hong SY, Dudhia J, Chen SH (2004) A revised approach to ice microphysical processes for the bulk parameterization of clouds and precipitation. Mon Weather Rev 132:103–120

Hong YNS-Y, Dudhia J (2006) A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon Weather Rev 134:2318–2341

Iacono MJ, Delamere JS, Mlawer EJ, Shephard MW, Clough SA, Collins WD (2008) Radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gases: calculations with the AER radiative transfer models. J Geophys Res 113:D13103. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD009944

Ikeda K, Rasmussen R, Liu C, Gochis D, Yates D, Chen F, Tewari M, Barlage M, Dudhia J, Miller K, Arsenault K, Grubišić V, Thompson G, Guttman E (2010) Simulation of seasonal snowfall over Colorado. Atmos Res 97(4):462–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosres.2010.04.010

Isotta F, Frei C, Weilguni V, Tadić MP, Lasségues P, Rudolf B, Pavan V, Cacciamani C, Antolini G, Ratto SM, Munari M, Micheletti S, Bonati V, Lussana C, Ronchi C, Panettieri E, Marigo G, Vertačnik G (2014) The climate of daily precipitation in the Alps: development and analysis of a high-resolution grid dataset from pan-Alpine rain-gauge data. Int J Climatol 34(5):1657–1675. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.3794

Jacob D, Petersen J, Eggert B, Alias A, Christensen O, Bouwer L, Braun A, Colette A, Déqué M, Georgievski G, Georgopoulou E, Gobiet A, Menut L, Nikulin G, Haensler A, Hempelmann N, Jones C, Keuler K, Kovats S, Yiou P (2014) Euro-cordex: new high-resolution climate change projections for European impact research. Reg Environ Change. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0499-2

Janjic ZI, Gerrity JP, Nickovic S (2001) An alternative approach to nonhydrostatic modeling. Mon Weather Rev 129(5):1164–1178. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2001)129<1164:AAATNM>2.0.CO;2

Jerez S, Montavez JP, Jimenez-Guerrero P, Gomez-Navarro JJ, Lorente-Plazas R, Zorita E (2013) A multi-physics ensemble of present-day climate regional simulations over the Iberian peninsula. Clim Dyn 40:3023–3046

Katragkou E, García-Díez M, Vautard R, Sobolowski S, Zanis P, Alexandri G, Cardoso RM, Colette A, Fernandez J, Gobiet A, Goergen K, Karacostas T, Knist S, Mayer S, Soares PMM, Pytharoulis I, Tegoulias I, Tsikerdekis A, Jacob D (2015) Regional climate Hindcast simulations within EURO-CORDEX: evaluation of a WRF multi-physics ensemble. Geosci Model Dev 8(3):603–618. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-8-603-2015

Kendon EJ, Roberts NM, Senior CA, Roberts MJ (2012) Realism of rainfall in a very high-resolution regional climate model. J Clim 25(17):5791–5806. https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00562.1

Kendon EJ, Roberts NM, Fowler HJ, Roberts MJ, Chan SC, Senior CA (2014) Heavier summer downpours with climate change revealed by weather forecast resolution model. Nat Clim Change 4:570–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2258