Abstract

Objectives

To assess the value of MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) for diagnosing local tumour regrowth during follow-up of organ preservation treatment after chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer.

Methods

Seventy-two patients underwent organ preservation treatment (chemoradiotherapy + transanal endoscopic microsurgery or “wait-and-see”) and were followed with MRI including DWI (1.5 T) every 3 -months during the first year and 6 months during following years. Two readers scored each MRI for local regrowth using a confidence level, first on standard MRI, then on standard MRI+DWI. Histology and clinical follow-up were the standard reference. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed and areas under the curve (AUC) and corresponding accuracy figures calculated on a per-scan basis.

Results

Four hundred and forty MRIs were assessed. Twelve patients developed local regrowth. AUC/sensitivity/specificity for standard MRI were 0.95/58 %/98 % (R1) and 0.96/58 % /100 % (R2). For standard MRI+DWI, these numbers were 0.86/75 %/97 % (R1) and 0.98/75 %/100 % (R2). After adding DWI, the number of equivocal scores decreased from 22 to 7 (R1) and from 40 to 20 (R2).

Conclusions

Although there was no overall improvement in diagnostic performance in terms of AUC, adding DWI improved the sensitivity of MRI for diagnosing local tumour regrowth and lowered the rate of equivocal MRIs.

Key Points

• DWI improves sensitivity for detecting local tumour regrowth after organ preservation treatment.

• In particular, DWI can aid in detecting small local recurrence.

• DWI reduces the number of equivocal scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nowadays, we are witnessing a paradigm shift in rectal cancer treatment away from standard resection towards minimally invasive surgery (transanal endoscopic microsurgery; TEM) or non-operative management (“wait-and-see”) in patients showing a clinically near-complete or complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (CRT)—albeit largely as part of observational trials at this time. Rates of local regrowth range from 6 to 25 % after TEM and from 5 to 13 % for wait-and-see, and excellent survival rates of greater than 90 % have been reported for both strategies [1–6]. Thus far, patients are generally followed using endoscopy and digital examination. However, studies have suggested that imaging—and MRI in particular—may also play an important role in patient surveillance [1, 7], all the more because of the necessity to monitor the (extra-)mesorectal lymph nodes that remain in situ and thus harbour the potential risk for tumour regrowth. Given the novelty of organ preservation treatment, no strong evidence yet exists regarding the potential role of MRI. Moreover, the ideal follow-up schedule has not yet been established. To date, reports from Brazil and the United States have followed a scheme in which imaging was performed “according to each patient’s requirement” [3, 6] or “at the discretion of the treating physicians” [5]. In the study by the Maastricht group imaging was routinely performed every 3–6 months [1]. The primary aim of close surveillance is the detection of any potential tumour regrowth as early as possible so that salvage surgery can still be performed without compromising the oncological outcome.

Morphological MRI is known to be less reliable for differentiating between post-treatment effects (i.e. fibrosis or bowel wall oedema after surgery/radiation) and tumours. From this perspective, the addition of diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may be beneficial. Various studies have shown the benefit of DWI for the detection of malignancies [8]. In rectal cancer, many reports support its potential beneficial role, especially in evaluating response to CRT [9–14]. Furthermore, DWI can aid in differentiating recurrent disease within the pelvis from areas of post-radiation/postoperative fibrosis [15, 16]. It may be particularly helpful for follow-up after organ preservation treatment, since tumour regrowth in these patients is typically still small and thus more difficult to detect on standard MRI.

The aim of this study, therefore, was to evaluate the value of MRI and test the hypothesis that adding DWI to standard (T2-weighted) MRI is of value for the diagnosis of local tumour regrowth during clinical follow-up of patients undergoing organ preservation treatment.

Methods

Patients

This study retrospectively evaluated 72 consecutive rectal cancer patients between September 2008 and July 2014 who were managed with organ preservation treatment after chemoradiotherapy at Maastricht University Medical Centre. Forty-nine patients were men, 23 were women, with a median age of 65 years (range 32–84). Seventeen patients with a small residual tumour (ycT1/2N0) after CRT were treated with TEM, and 55 patients with a complete response (ycT0/N0) were followed according to a “wait-and-see” policy. The routine CRT scheme consisted of 28 × 1.8 Gy + 2 × 825 mg/m2/d capecitabine. The majority (66/72) of patients were treated/followed as part of a clinical trial [1], and the remaining six were followed “off-study” (e.g. because they were included prior to the trial period or had comorbidity/metastases excluding them from formal trial participation). MR imaging including DWI was routinely performed every 3 months during the first year and every 6 months during the following years [1].

MR imaging

MR imaging was performed at 1.5 T (Intera [Achieva] or Ingenia MRI systems; Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) using a phased-array surface coil with patients in feet-first supine position. Patients did not receive bowel preparation. The protocol included T2-weighted fast spin-echo sequences in three planes and an axial diffusion-weighted sequence (highest b-value b1000). Detailed scan parameters are provided in Table 1. Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps in greyscale were automatically generated by the operating system. The axial T2-weighted and DWI sequences were angled in identical planes perpendicular to the rectal lumen at the site of the former tumour bed or, in the case of a suspected mass on the planning images, perpendicular to the mass.

Image evaluation

Each individual follow-up MRI examination was assessed by two readers (MJL and DMJL) with 9 (reader 1; R1) and 5 years (reader 2; R2) of specific experience in reading rectal MRI. The readers assessed the MRI examinations independently and were blinded to each other’s results. They were aware of the primary treatment (i.e. TEM or wait-and-see) and had insight into the primary staging MRI and restaging MRI + endoscopy (including biopsy results) performed 8 weeks after completion of CRT, i.e. prior to initiation of the organ preservation treatment/follow-up. The readers were blinded to histopathological outcome in the case of TEM surgery and to all other data obtained during follow-up, including imaging, endoscopy, and biopsy results, information on any potential salvage surgical procedures, and histopathological outcome.

For each individual MR examination, the readers first evaluated the standard T2-weighted images and recorded the likelihood of tumour regrowth using a five-point confidence level scale (0 = definitely no regrowth, 1 = probably no regrowth, 2 = possibly no/possibly regrowth, 3 = probably regrowth, and 4 = definitely regrowth). In the same reading session, the DWI images (+ ADC map) were revealed, and the readers re-evaluated the T2-weighted and DWI images together (side by side) using the same confidence level score.

Standard of reference

All tumour regrowth was histologically confirmed by biopsy and/or after surgical resection. In patients without regrowth, the absence of a tumour was confirmed by a combination of the following: (a) no abnormalities on corresponding endoscopy, (b) negative biopsy results, and (c) no evidence of tumour regrowth during clinical, endoscopic and imaging follow-up over a median follow-up period of 38 months (range 19–78 months).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Darmonk, NY, USA). Diagnostic performance was assessed on a per-scan basis, in which each individual MR examination was considered an independent event. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed and areas under the ROC curve (AUC) were calculated. Accuracy figures were calculated after dichotomisation of the scores with the cut-off (defined before onset of the study) set between 2 = possibly/possibly no regrowth and 3 = probably regrowth. Kappa values with quadratic kappa weighting were calculated to determine interobserver agreement.

Results

Patient and treatment characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are given in Table 2. The 72 study patients together underwent a total of 440 follow-up MRIs (range 1–13 per patient), of which 92 were performed after TEM and 348 during wait-and-see. Twelve patients had tumour regrowth (5/17 TEM patients and 7/55 wait-and-see patients): regrowth of two tumours occurred within 6 months (both during wait-and-see), seven between 6 and 12 months (four after TEM, three during wait-and-see), and three after 12–24 months (one after TEM, two during wait-and-see). No regrowth occurred after 24 months of follow-up. The regrowth was luminal (at the site of the previous tumour) in 10/12 patients; the other two involved nodal regrowth.

Effect of DWI on number of equivocal scores

On standard T2W MRI, R1 assigned an equivocal (confidence level 2) score to 22/440 or 5 % of the examinations (12 % after TEM, 3 % during wait-and-see) and R2 to 40/440 or 9 % (16 % after TEM, 7 % during wait-and-see). After the addition of DWI, the equivocal scores decreased to 7/440 or 2 % (1 % after TEM, 2 % during wait-and-see) for R1 and 20/440 or 5 % (8 % after TEM, 4 % during wait-and-see) for R2. A representative example of a case where the addition of DWI increased the readers’ confidence is given in Fig. 1.

Example of a male patient who was followed according to a wait-and-see policy and who developed local tumour regrowth at the location of his primary rectal tumour after 21 months of follow-up. (a) Axial T2-weighted image of the primary tumour (arrows) before chemoradiotherapy. (b) Follow-up axial T2-weighted image of the former tumour location at the time of the regrowth: no clear isointense mass or wall thickening was observed. (c) Corresponding diffusion-weighted image that clearly shows a focal area of high signal indicative of tumour regrowth. This was later confirmed as a pT2 rectal tumour

The distribution of equivocal scores during early (≤6 months) and late (>6 months) follow-up and between the wait-and-see and TEM groups is given in Table 3. The majority of equivocal scores occurred during early follow-up: 77 % (17/22; R1) and 53 % (21/40; R2) for standard T2W MRI alone, and 71 % (5/7; R1) and 50 % (10/20; R2) for T2W MRI + DWI. In the TEM group in particular, the equivocal scores largely occurred within the first 6 months: 82 % (9/11; R1) and 67 % (10/15; R2) for T2W MRI, and 100 % (1/1; R1) and 57 % (4/7; R2) for T2W MRI + DWI. A representative case in which equivocal scores changed over long-term follow-up after TEM is given in Fig. 2.

Follow-up axial T2-weighted and diffusion-weighted images of a male patient who underwent transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) after chemoradiotherapy. (a) Two months after the TEM procedure, the axial T2-weighted images show a defect in the rectal wall, with fibrotic changes at the TEM location (arrows). (b) On DWI, a focal high signal intensity is visible, indicated by the circle. The readers interpreted this high signal as suspicious for local tumour regrowth. (c) Five months later, the T2-weighted images show a similar scar, with further increased fibrosis (arrows). (d) On the corresponding diffusion-weighted image, the previous high signal has disappeared, and there is no remaining suspicion of tumour regrowth. Long-term follow-up confirmed that this patient had no tumour regrowth

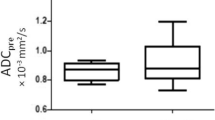

Diagnostic performance

The ROC curves for both readers are displayed in Fig. 3. AUCs were 0.95 (R1) and 0.96 (R2) for standard T2W MRI, and 0.86 (R1) and 0.98 (R2) for standard T2W MRI + DWI (p = 0.16 for R1 and p = 0.02 for R2). Diagnostic accuracy figures are given in Table 4. For R1, sensitivity and specificity were 58 % and 98 %, respectively, for standard T2W MRI versus 75 % and 97 % for standard T2W MRI + DWI. For R2, these numbers were 58 % and 100 % for standard T2W MRI versus 75 % and 100 % for standard T2W MRI + DWI. The majority of false positives after the addition of DWI (10/12 = 83 % for R1 and 2/2 = 100 % for R2) occurred in patients who had no histologically proven tumour regrowth at the time of the “false-positive” finding, but developed tumour regrowth later during follow-up.

Interobserver agreement

Overall, interobserver agreement between the two readers was moderate for both standard T2-weighted MRI (κ 0.55) and the combined reading of standard T2W MRI + DWI (κ 0.56). For the “late” follow-up examinations (performed after 6 months of follow-up), interobserver agreement was moderate for T2-weighted MRI (κ 0.57) and good for T2W MRI + DWI (κ 0.64).

Discussion

Adding DWI to standard T2W MRI did not result in an overall improvement in diagnostic performance in terms of AUC, but it did result in improved sensitivity for the detection of local tumour regrowth during surveillance of patients undergoing organ preservation treatment after chemoradiotherapy: sensitivity increased from 58 % to 75 % for two individual readers. A striking finding was that although the rate of “false-positive” findings increased after the addition of DWI, the majority of these false positives occurred in patients who developed tumour regrowth later during follow-up. Finally, the addition of DWI substantially reduced the number of equivocal scores (from 22 to 7 for R1 and from 40 to 20 for R2), thereby increasing the chance of a conclusive MR outcome.

Our study is the largest to date focussing on the detection of tumour regrowth with MRI during the surveillance of patients treated with organ preservation. Previous studies (Colosio et al. and Lambregts et al.) have focussed on imaging in patients after routine surgical treatment. In these studies, MRI was performed only in the case of clinically suspected recurrence (clinical symptoms or rising carcinoembryonic antigen levels). Colosio et al. [17] reported an increase in sensitivity of 7–16 % for two of three readers in a group of 52 surgically treated rectal cancer patients. In their study, DWI was beneficial only for the less experienced resident readers and not for a senior reader. A similar study by Lambregts et al. found no significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy with the addition of DWI in 42 patients after routine surgical resection [16]. We hypothesize that the disparity in results between our study and these reports can be explained in part by the difference in clinical setting. Symptomatic regrowth/recurrence is often diagnosed in a more advanced stage when morphological distortions in the tumour bed can be clearly visualised already with standard MRI. However, in our cohort, where asymptomatic patients were routinely monitored with repetitive MR assessment, the regrowth was small (7–33 mm). These cases of small regrowth are challenging to detect on standard MRI, particularly within post-treatment fibrosis. In such cases, the use of DWI can help the reader spot any suspicious signals of tumour regrowth. In two of our study cases, DWI indeed aided the detection of a small tumour regrowth that was not detected on T2-weighted MRI (Fig. 1). In two other cases, the addition of DWI increased the confidence of R2 from level 3 (probably tumour regrowth) to level 4 (definitely tumour regrowth).

A striking finding in the present study was the relatively high rate of false positives after the addition of DWI, particularly for R1. Interestingly, the majority of these false positives (10/12 for R1 and 2/2 for R2) occurred in patients who developed tumour regrowth later during follow-up. At the time of the “false-positive” DWI findings, no changes suspicious for tumour recurrence were visualised on endoscopy, and biopsy results (when available) were negative. The latter served as the standard of reference, and thus these patients were considered false-positive on DWI at that time in our analyses. This raises the question, however, of whether these false positives were actual false positives on DWI or whether these DWI findings might have been early features of regrowth. This would suggest that in some cases, primarily those in which tumour growth starts within the fibrotic mass without distortion of the lumen, DWI signal changes may precede any visible changes on endoscopy. The remaining two false-positive cases for R1 both occurred within the first 6 months of follow-up (one after TEM, one during wait-and-see). Shortly after treatment, postoperative/post-radiation inflammatory changes may still be present, in which case an accumulation of inflammatory cells, granulomas, and lymphoid aggregates can lead to relatively high cellularity and thus restricted diffusion. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease, this phenomenon is used as a diagnostic criterion on DWI to detect active inflammation [18, 19], but in the setting of surveillance of patients after organ preservation treatment, these effects may hamper image interpretation and mimic a tumour.

One of the benefits of DWI is that it offered a conclusive outcome in several cases (5–9 % of all MRIs) where the T2W MRI resulted in equivocal scores. In clinical practice, an equivocal MRI would require additional exams. Adding a DWI sequence may thus render such additional exams unnecessary. The effect of DWI was most apparent in patients followed after TEM: the rate of equivocal scores on standard T2W MRI was 12–16 % after TEM versus only 3–7 % for the wait-and-see group. Furthermore, within the TEM group, most of the equivocal scores (67–82 %) occurred during the first 6 months of follow-up. This makes sense, since post-surgical effects such as oedema and tissue inflammation will still be present early after surgery, rendering the images more difficult to interpret. In patients undergoing wait-and-see, such postsurgical effects are absent, allowing for easier interpretation of T2-weighted images, and thus explaining the higher confidence for both readers. In the wait-and-see group, the beneficial effect of DWI in increasing the readers’ confidence was therefore less obvious.

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature. The results are based on a per-scan assessment of individual MR examinations. This setting was chosen to reflect daily practice and to gain insight into the strengths and weaknesses of MRI and DWI during regulated follow-up, but may not translate into the true overall diagnostic performance of MRI and DWI on a patient level. However, the 17 % increase in sensitivity can be directly translated to the effect on sensitivity at a patient level, given that only one event/regrowth occurred per patient. Given the limited number of cases of local regrowth, the confidence intervals (particularly for sensitivity and positive predictive value) are relatively wide. Interobserver agreement was moderate for T2-weighted MRI and moderate to good after the addition of DWI. The moderate agreement is likely attributable in part to the fact that one of the two readers assigned a relatively large number of equivocal scores, particularly for T2W MRI. Finally, in the setting of protocols used for daily clinical practice, a variation in sequence parameters was present as a result of protocol optimization over the years. Although the reading was designed in a way that only visual evaluation of DWI was performed using the same b-value images (b1000), variations in image quality may have introduced some bias.

In conclusion, this study shows that although the addition of DWI to a standard rectal MRI protocol may not result in a significant overall improvement in diagnostic performance in terms of area under the ROC curve, it can help to improve the sensitivity of MRI in detecting small local recurrence during the surveillance of patients after organ preservation treatment. In fact, it may be true that in the case of tumour regrowth, changes in DWI precede any changes detectable at endoscopy. A second important benefit from the addition of DWI is that it reduces the number of equivocal findings, particularly during early follow-up after TEM surgery, and thus enhances the chance of a conclusive MR outcome.

References

Maas M, Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM et al (2011) Wait-and-see policy for clinical complete responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 29:4633–4640

Lezoche G, Baldarelli M, Guerrieri M et al (2008) A prospective randomized study with a 5-year minimum follow-up evaluation of transanal endoscopic microsurgery versus laparoscopic total mesorectal excision after neoadjuvant therapy. Surg Endosc 22:352–358

Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Proscurshim I et al (2006) Patterns of failure and survival for nonoperative treatment of stage c0 distal rectal cancer following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy. J Gastrointest Surg 10:1319–1328, discussion 1328–1329

Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Lynn PB et al (2013) Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for residual rectal cancer (ypT0-2) following neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy: another word of caution. Dis Colon Rectum 56:6–13

Smith JD, Ruby JA, Goodman KA et al (2012) Nonoperative management of rectal cancer with complete clinical response after neoadjuvant therapy. Ann Surg 256:965–972

Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues J, Sao Juliao GP et al (2014) Local recurrence after complete clinical response and watch and wait in rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: impact of salvage therapy on local disease control. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 88:822–828

Habr-Gama A, Sabbaga J, Gama-Rodrigues J et al (2013) Watch and wait approach following extended neoadjuvant chemoradiation for distal rectal cancer: are we getting closer to anal cancer management? Dis Colon Rectum 56:1109–1117

Charles-Edwards EM, deSouza NM (2006) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and its application to cancer. Cancer Imaging 6:135–143

Lambregts DM, Vandecaveye V, Barbaro B et al (2011) Diffusion-weighted MRI for selection of complete responders after chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer: a multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol 18:2224–2231

Dzik-Jurasz A, Domenig C, George M et al (2002) Diffusion MRI for prediction of response of rectal cancer to chemoradiation. Lancet 360:307–308

Kim SH, Lee JM, Hong SH et al (2009) Locally advanced rectal cancer: added value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the evaluation of tumor response to neoadjuvant chemo- and radiation therapy. Radiology 253:116–125

Beets-Tan RG, Lambregts DM, Maas M et al (2013) Magnetic resonance imaging for the clinical management of rectal cancer patients: recommendations from the 2012 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 23:2522–2531

Sun YS, Zhang XP, Tang L et al (2010) Locally advanced rectal carcinoma treated with preoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy: preliminary analysis of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for early detection of tumor histopathologic downstaging. Radiology 254:170–178

Cai P-Q, Wu Y-P, An X et al (2014) Simple measurements on diffusion-weighted MR imaging for assessment of complete response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Eur Radiol 24:2962–2970

Nishie A, Stolpen AH, Obuchi M, Kuehn DM, Dagit A, Andresen K (2008) Evaluation of locally recurrent pelvic malignancy: performance of T2- and diffusion-weighted MRI with image fusion. J Magn Reson Imaging 28:705–713

Lambregts DM, Cappendijk VC, Maas M, Beets GL, Beets-Tan RG (2011) Value of MRI and diffusion-weighted MRI for the diagnosis of locally recurrent rectal cancer. Eur Radiol 21:1250–1258

Colosio A, Soyer P, Rousset P et al (2014) Value of diffusion-weighted and gadolinium-enhanced MRI for the diagnosis of pelvic recurrence from colorectal cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 40:306–313

Oussalah A, Laurent V, Bruot O et al (2010) Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance without bowel preparation for detecting colonic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 59:1056–1065

Kiryu S, Dodanuki K, Takao H et al (2009) Free-breathing diffusion-weighted imaging for the assessment of inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease. J Magn Reson Imaging 29:880–886

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Regina Beets-Tan. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. The authors state that this work has not received any funding. One of the authors has significant statistical expertise. A portion of the patients included were treated with organ preservation treatment as part of a clinical trial. This trial was approved by the institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study who were treated according to the clinical trial described in point 6. For the other patients, written informed consent was not required because of the retrospective nature of the study, for which Dutch national law does not require IRB approval. Some study subjects or cohorts have been previously reported in Maas M, et al. Wait-and-see policy for clinical responders after chemoradiation for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011 29(35):4633–40. This publication concerned a report on a clinical trial (see point 6) focussing on the selection and outcome of patients treated according to a wait-and-see policy. Methodology: retrospective, diagnostic or prognostic study, performed at one institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lambregts, D.M.J., Lahaye, M.J., Heijnen, L.A. et al. MRI and diffusion-weighted MRI to diagnose a local tumour regrowth during long-term follow-up of rectal cancer patients treated with organ preservation after chemoradiotherapy. Eur Radiol 26, 2118–2125 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-4062-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-4062-z