Abstract

Objectives

To assess the clinical relevance of T2 relaxation times, measured by 3D triple-echo steady-state (3D-TESS), in knee articular cartilage compared to conventional multi-echo spin-echo T2-mapping.

Methods

Thirteen volunteers and ten patients with focal cartilage lesions were included in this prospective study. All subjects underwent 3-Tesla MRI consisting of a multi-echo multi-slice spin-echo sequence (CPMG) as a reference method for T2 mapping, and 3D TESS with the same geometry settings, but variable acquisition times: standard (TESSs 4:35min) and quick (TESSq 2:05min). T2 values were compared in six different regions in the femoral and tibial cartilage using a Wilcoxon signed ranks test and the Pearson correlation coefficient (r). The local ethics committee approved this study, and all participants gave written informed consent.

Results

The mean quantitative T2 values measured by CPMG (mean: 46±9ms) in volunteers were significantly higher compared to those measured with TESS (mean: 31±5ms) in all regions. Both methods performed similarly in patients, but CPMG provided a slightly higher difference between lesions and native cartilage (CPMG: 90ms→61ms [31%],p=0.0125;TESS 32ms→24ms [24%],p=0.0839).

Conclusions

3D-TESS provides results similar to those of a conventional multi-echo spin-echo sequence with many benefits, such as shortening of total acquisition time and insensitivity to B1 and B0 changes.

Key points

• 3D-TESS T 2 mapping provides clinically comparable results to CPMG in shorter scan-time.

• Clinical and investigational studies may benefit from high temporal resolution of 3D-TESS.

• 3D-TESS T 2 values are able to differentiate between healthy and damaged cartilage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transverse relaxation time (T2) mapping in articular cartilage has been previously reported as a reliable marker for the evaluation of collagen matrix and water content. The changes in T2 values have been demonstrated to correlate with alterations in water content, as well as collagen structure and organization, and are linked to changes in hyaline cartilage and its depletion [1–3]. To date, T2 mapping of cartilage has been successfully used in many applications related to biomechanical and biochemical analysis of cartilage tissue [4–17]. Although the loss of glycosaminoglycans is an early sign of osteoarthritis (OA) and collagen depletion occurs in later stages, the potential of T2 as a marker for the grading of cartilage degeneration in OA has also been demonstrated [18].

T2 maps are typically calculated from a series of T2-weighted images acquired with different echo times. However, the accuracy and reliability of the resulting T2 maps is highly dependent on the method used to record the initial T2-weighted images.

A multi-spin-echo pulse sequence [e.g., Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill (CPMG) [19]] is a widely used method for in vivo T2 mapping. This sequence acquires signals from multiple time points along the T2 decay for each k-space line during a single repetition time. However, this is accompanied by the consequent signal contamination by stimulated echoes [20]. Acquiring the complete T2 decay curve is also time-consuming and frequently requires segmented imaging strategies.

Another possibility for acquiring T2-weighted images is a single-spin-echo strategy. It is well known that maps generated with a series of single-echo spin-echo (SE) images suffer from steady state effects (i.e., different T1 weightings) in the images. To prevent this, long transverse relaxation (TR) times are necessary, which may limit clinical applications. In addition, the total scan time is substantially longer compared to CPMG because the sequence must be repeated for each echo time separately [21].

Recently, a triple-echo steady-state (TESS) relaxometry method was introduced for fast and accurate T2 and T1 mapping [22, 23]. This sequence has several advantages over conventional T2 mapping: it is very fast, the data are acquired in a single scan, and the quantification of T2 is markedly insensitive to B1. To date, the clinical performance of 3D-TESS for T2 mapping in cartilage has not yet been evaluated.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the clinical relevance of T2 relaxation times, measured by three-dimensional (3D) triple-echo steady-state (3D-TESS), in knee articular cartilage compared to conventional multi-echo spin-echo T2-mapping.

Materials and methods

Patients

The right knees of 10 patients (35.1 ±10.5 years) with a focal cartilage lesion and 13 age-matched volunteers (31.4 ±9.4 years) were measured in this prospective study. The local ethics committee approved this study, and all participants gave written, informed consent. Inclusion criteria for volunteers were: no signs of any cartilage lesion in the knee joint on standard morphological magnetic resonance (MR) sequences; and no meniscal and ligament damage. In patients, only subjects with focal lesions in the femoral cartilage were included. Three patients underwent surgical procedures on the femoral cartilage (matrix-associated chondrocyte transplantation [MACT], Pridie drilling, and mosaicplasty), and the remaining patients were diagnosed with chondropathy grade 2 to 4 according to the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) classification.

MR examinations

All subjects underwent MR examinations of the knee joint on a 3 Tesla Tim TRIO MR scanner (Siemens HealthCare, Erlangen, Germany). An eight-channel knee coil (Siemens HealthCare, Erlangen, Germany) was used for all MR scans. The examination consisted of two methods: a multi-echo multi-slice spin echo sequence (CPMG) as a reference method for T2 mapping; and a 3D-TESS with the exact same geometry settings as in the CPMG sequence but with two modifications, a standard (TESSs, acquisition time 4:35 min) and a quick (TESSq, acquisition time 2:05 min) sequence. For TESSq, the total acquisition time was reduced by using a phase-and-slice partial Fourier acquisition. The abbreviation TESS refers to TESSs throughout the entire manuscript. With TESS imaging, the three steady-state free precession signal amplitudes (F1, F0, and F-1) were acquired within separate radiofrequency cycles (each signal within one at the same echo time) to enable a shorter repetition time and mitigate possible susceptibility effects [22]. CPMG T2 maps were calculated using the Syngo console tool Mapit (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), and, for 3D-TESS, the scripting framework IceLuva was used [24]. To ensure the possibility of evaluating all T2 maps at once by copying regions-of-interest (ROIs), the frequency calibration was double-checked before each scanning to avoid chemical shift artefacts. The summary of all sequence parameters is in the Table 1.

MR data evaluation

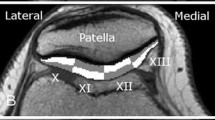

T2values were compared in six different regions in the femoral (anterior AFC, mid MFC, posterior PFC) and tibial (anterior ATC, mid MTC, posterior PTC) cartilage (Fig. 1). Each ROI was further subdivided into equally thick superficial and deep layers. The ROIs were selected in the JiveX DICOM Viewer (JiveX 4.3; VISUS Technology Transfer GmbH, Bochum, Germany) by a radiologist (N.N.) with 16 years of experience. To assess inter-observer variability, another two observers (N.N. 10 years of experience, N.N., 15 years of experience), blinded to previous results, evaluated five volunteers and five patients, and the coefficient of variation was calculated.

Statistical analysis

The difference between absolute T2 values calculated with different mapping techniques (CPMG versus 3D-TESS and 3D-TESSq versus 3D-TESSs) was expressed as a P-value calculated by a Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated, and standard deviations (SDs) of the ROIs were compared. Both absolute values and percentage differences between CPMG and 3D-TESS were evaluated. In patients, the T2 values from focal chondral lesions were compared to the adjacent native cartilage and the ability to differentiate between healthy and depleted cartilage was assessed. All statistical calculations were performed in SPSS version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and a P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The subjects had the following demographic characteristics: volunteers (5 males, mean age 28.8 ±5.8 years, mean BMI 23.8 ±3.7; 8 females, mean age 33.1 ±11.1 years, mean BMI 22.8 ±2.9), patients (8 males, mean age 36.8 ±11 years, mean BMI 24.7 ±2.6; 2 females mean age 28.1 ±4.7 years, mean BMI 22.9 ±4.8). Both techniques provided artefact-free T2 maps (Figs. 2, 3 and 4). The T2 values measured with 3D-TESS were systematically lower than those measured with CPMG. When all cartilaginous regions were pooled, the average T2 values were 52 ±10 ms (CPMG) and 29 ±5 ms (3D-TESS). For individual cartilage layers separately, the mean T2 values in the superficial layer were 59 ±7 ms (CPMG) and 33 ±2 ms (TESS), and in the deep layer, 46 ±9 ms (CPMG) and 27 ±5 ms (TESS). In general, the difference between 3D-TESS and CPMG T2 values was statistically significant in all regions. The T2 values measured by CPMG showed a high correlation with T2 values calculated from 3D-TESS, primarily in the weight-bearing zones of the tibia and femur, and the other zones correlated only moderately (Tables 2 and 3).

A: T2 map acquired by CPMG, pseudo-colour-coded and overlaid on a morphological T2 –weighted image from a 32-year-old healthy volunteer (TE = 11.9 ms); B: T2 map acquired by 3D-TESS, pseudo-colour-coded and overlaid on the second acquired MR image (F0). The typical zonal stratification in cartilage is observable with both techniques. However, T2(CPMG) provides apparently higher dynamic contrast of T2 values with better depiction of cartilaginous layers

The SDs for TESS-T2 were slightly lower than for CPMG-T2; however, this difference was not statistically significant (28 ±6 % and 30 ±12 %, P = 0.579). When comparing cartilage layers, the SD did not demonstrate any significant differences between the superficial (TESS 26 ±8 %, CPMG 32 ±10 %) and the deep zone (TESS 29 ±7 %, CPMG 29 ±8 %).

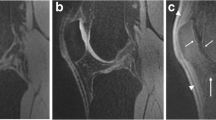

Both T2 mapping techniques were able to detect the changes between chondral lesions and native cartilage. For CPMG, the mean T2 in cartilaginous lesions was 90 ±50 and in native cartilage, it was 62 ±25 ms. For 3D-TESS, the mean T2 in cartilaginous lesions was 32 ±6, and in native cartilage, it was 24 ±8 ms. Example T2 maps of native and damaged cartilage are depicted in Fig. 5.

A: T2 map acquired by CPMG, pseudo-colour-coded and overlaid on a morphological image of a 41-year-old patient with Pridie drilling on the medial femoral condyle (TE = 11.9 ms); the ratio of native and lesion cartilage T2s is 0.81. B: T2 map acquired by 3D-TESS, pseudo-colour-coded and overlaid on the second acquired MR image (F0); the ratio of native and lesion cartilage T2s is 0.83. Focal increase in T2 values is observable with both techniques (’lesion’). Bone oedema is also present (large arrow). The dynamic range of the CMPG T2 map is higher compared to the 3D-TESS T2 map, therefore, the lesion appears to be more diffuse, although the ratios of native and lesion cartilage T2s are comparable between CPMG and 3D-TESS

The comparison between TESSq and TESSs showed almost no difference between T2 values. On average, T2(3D-TESSq) was 31 ±2 ms and T2(3D-TESSs) was 31 ±3 ms. The mean Pearson correlation coefficient calculated from the whole cartilage in volunteers and patients was 0.816, ranging from 0.750 to 0.911 in different cartilage regions. The example of correlation in the femoral and tibial cartilage is depicted in Fig. 6.

The mean coefficient of variation between different observers was 6.4 % (femoral cartilage, T2(CPMG)), 8.1 % (tibial cartilage, T2(CPMG)), 5.8 % (femoral cartilage, T2(3D-TESS)) and 10.8 % (tibial cartilage, T2 (3D-TESS)).

Discussion

The results of our study indicate that T2 relaxation times in the cartilage of the knee joint, calculated from a novel 3D-TESS sequence, are highly consistent with those calculated by a classic CPMG sequence. Although the absolute T2 values were significantly lower for 3D-TESS, this decrease was systematic, and the T2 values were highly correlated between 3D-TESS and CPMG in most of the selected regions. In Ref. [23], the authors demonstrated that TESS-based T2 quantification provides accurate T2 values in excellent agreement with single-echo spin echo reference measurements, while CPMG resulted in a substantial overestimation of T2 due to stimulated echo contributions. The observed significant difference between TESS-T2 and CPMG-T2 may, thus, be mainly attributed to stimulated echo contamination present in the CPMG scans. In addition, the increase of T2 values in the region affected by the magic angle effect (posterior femoral condyle in our case) was observable with both techniques. According to Mosher et al., the greatest variation in cartilage T2 with regard to the magic angle effect is observed in the superficial 20 % of cartilage [25]. This is in concordance with the presented results, although we divided the cartilage into two layers rather than three because of limited in vivo resolution.

The great advantage of 3D-TESS for cartilage T2 mapping is the decrease of total scan time. At our institute, the routine (CPMG) T2 mapping at 3T requires four and a half minutes. In our study, for f comparison purposes, we primarily used a total-acquisition-time-matched version of 3D-TESS. However, we were able to decrease the acquisition time of 3D-TESS down to 2:05 min by using a phase-and-slice partial Fourier sampling, keeping the resulting cartilage T2 values without a statistically significant change, compared to the total-acquisition-time-matched version of 3D-TESS. This feature would be extremely beneficial in studies where a higher temporal resolution is desired. A typical example would be the physiological analysis of cartilage changes during in vivo loading.

For instance, Nishii et al. used CPMG T2 mapping in their in vivo loading study with a 13-minute long CPMG sequence version [26]. Mamisch et al. evaluated the unloading effect on articular cartilage prior to and during the MR scan with a 4:09-minute long CPMG-based sequence [27]. In another study, the changes in cartilage water content in cartilage under compression were detected using T2 mapping, with an acquisition time of 7:30 minutes [28]. The limitation with all such experiments is that the decrease of T2 values during the MR experiment under loading cannot be excluded with certainty. Therefore, there is a need to shorten the acquisition time of T2 experiments to a minimum. In this case, 3D-TESS seems to be the ideal T2 mapping technique for such investigational applications. However, fast T2 mapping with 3D-TESS could also be beneficial for routine clinical applications, providing increased patient comfort and reducing costs.

We also hypothesized that the SD of T2 from ROIs selected on cartilage would be lower with 3D-TESS due to its more robust T2 calculation. The results, however, showed the SDs were the same, no matter which technique was used. Moreover, SDs calculated in our study were consistent with those published in other studies; e.g., Nieminen et al. found an SD of T2 in bovine cartilage ranging from 12.5 to 29 % [29], and Kurkijärvi et al., as well as Juras et al., observed an SD of T2 in human cadaver samples between 13.3 - 41.5 % [30] and 23 - 34 %, respectively [31]. Since all of these studies were performed in vitro, it can be assumed that motion artefacts did not contribute to those high SDs. High SDs of T2 in cartilage tissue could be attributed to relatively large tissue anisotropy and heterogeneity due to collagen fibre organization [32].

In has been previously demonstrated that focal cartilage lesions, as well as the cartilage repair tissue, are characterized by T2 elevation [14, 33–35]. This focal T2 increase was attributed either to collagen disorganization or to cartilage swelling, accompanied by water volume increase. Similarly, in our study, we observed an increase in T2 differences between native cartilage and lesions. For CPMG, this difference was slightly larger (32 %) compared to 3D-TESS (24 %). Since both differences were statistically significant, the clinical relevance of both techniques is comparable.

Our study has some limitations. Our patient group was relatively small and the diagnoses were inconsistent. It would be necessary to validate these findings in a larger patient group with the same type of cartilage lesions or repair tissues. Moreover, the lesions selected in our study were quite severe, resulting in relatively large T2 value changes. It would be interesting, however, to investigate the sensitivity of 3D-TESS to subtle T2 changes, where 3D-TESS would be expected to perform better as it provides more accurate T2 values. This is primarily because 3D-TESS is less prone to errors, while CPMG substantially overestimates T2 due to stimulated echo contributions.

3D-TESS is insensitive to B0 and B1 heterogeneities and may, thus, provide more accurate T2 values with lower SDs. Moreover, the three-dimensional nature of 3D-TESS allows reformatting of T2 maps in arbitrary planes, expanding the usefulness of this sequence to other tissues (e.g., ligaments, menisci) or more challenging joints for MR imaging (MRI; e.g., hip, shoulder, temporo-mandibular). The 3D-TESS sequence also produces T1 maps (not tested in this study) that may have great clinical potential, but require additional B1 mapping scans.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate the clinical utility of a 3D-TESS sequence for T2 mapping of human knee cartilage. 3D-TESS provides results similar to those of a conventional multi-echo spin-echo sequence with many benefits, such as shortening of total acquisition time and insensitivity to B1 and B0 changes. T2 mapping with 3D-TESS was able to differentiate between healthy and damaged cartilage tissue, indicating its great potential for clinical studies.

Abbreviations

- TESS:

-

Triple-echo steady state sequence

- CPMG:

-

Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill sequence

References

Duewell SH, Ceckler TL, Ong K et al (1995) Musculoskeletal Mr-Imaging at 4 T and at 1.5 T - Comparison of Relaxation-Times and Image-Contrast. Radiology 196:551–555

Mlynarik V, Degrassi A, Toffanin R, Vittur F, Cova M, PozziMucelli RS (1996) Investigation of laminar appearance of articular cartilage by means of magnetic resonance microscopy. Magn Reson Imaging 14:435–442

Mlynarik V, Szomolanyi P, Toffanin R, Vittur F, Trattnig S (2004) Transverse relaxation mechanisms in articular cartilage. J Magn Reson 169:300–307

Nieminen MT, Toyras J, Laasanen MS, Silvennoinen J, Helminen HJ, Jurvelin JS (2004) Prediction of biomechanical properties of articular cartilage with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. J Biomech 37:321–328

Dunham J, Chambers MG, Jasani MK, Bitensky L, Chayen J (1990) Changes in the Orientation of Proteoglycans during the Early Development of Natural Murine Osteo-Arthritis. J Orthop Res 8:101–104

Mosher TJ, Dardzinski BJ, Smith MB (2000) Human articular cartilage: Influence of aging and early symptomatic degeneration on the spatial variation of T2 - Preliminary findings at 3 T. Radiology 214:259–266

Mosher TJ, Smith HE, Collins C et al (2005) Change in knee cartilage T2 at MR imaging after running: A feasibility study. Radiology 234:245–249

Apprich S, Mamisch TC, Welsch GH et al (2012) Quantitative T2 mapping of the patella at 3.0 T is sensitive to early cartilage degeneration, but also to loading of the knee. Eur J Radiol 81:E438–E443

Mamisch TC, Trattnig S, Quirbach S, Marlovits S, White LM, Welsch GH (2010) Quantitative T2 Mapping of Knee Cartilage: Differentiation of Healthy Control Cartilage and Cartilage Repair Tissue in the Knee with Unloading-Initial Results. Radiology 254:818–826

Alhadlaq HA, Xia Y (2005) Modifications of orientational dependence of microscopic magnetic resonance imaging T-2 anisotropy in compressed articular cartilage. J Magn Reson Imaging 22:665–673

Nag D, Liney GP, Gillespie P, Sherman KP (2004) Quantification of T-2 relaxation changes in articular cartilage with in situ mechanical loading of the knee. J Magn Reson Imaging 19:317–322

Shiomi T, Nishii T, Tanaka H et al (2010) Loading and knee alignment have significant influence on cartilage MRI T2 in porcine knee joints. Osteoarthr Cartil 18:902–908

Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Marlovits S et al (2009) Quantitative T2 Mapping during Follow-up after Matrix-Associated Autologous Chondrocyte Transplantation (MACT): Full-Thickness and Zonal Evaluation to Visualize the Maturation of Cartilage Repair Tissue. J Orthop Res 27:957–963

Welsch GH, Mamisch TC, Domayer SE et al (2008) Cartilage T2 assessment at 3-T MR imaging: In vivo differentiation of normal hyaline cartilage from reparative tissue after two cartilage repair procedures - Initial experience. Radiology 247:154–161

Bittersohl B, Miese FR, Dekkers C et al (2013) T2* mapping and delayed gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in cartilage (dGEMRIC) of glenohumeral cartilage in asymptomatic volunteers at 3 T. Eur Radiol 23:1367–1374

Kretzschmar M, Bieri O, Miska M et al (2015) Characterization of the collagen component of cartilage repair tissue of the talus with quantitative MRI: comparison of T2 relaxation time measurements with a diffusion-weighted double-echo steady-state sequence (dwDESS). Eur Radiol 25:980–986

Alizai H, Roemer FW, Hayashi D, Crema MD, Felson DT, Guermazi A (2015) An update on risk factors for cartilage loss in knee osteoarthritis assessed using MRI-based semiquantitative grading methods. Eur Radiol 25:883–893

Dunn TC, Lu Y, Jin H, Ries MD, Majumdar S (2004) T2 relaxation time of cartilage at MR imaging: Comparison with severity of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology 232:592–598

Meiboom S, Gill D (1958) Modified Spin-Echo Method for Measuring Nuclear Relaxation Times. Rev Sci Instrum 29:688–691

Ben-Eliezer N, Sodickson DK, Block KT (2014) Rapid and Accurate T2 Mapping from Multi–Spin-Echo Data Using Bloch-Simulation-Based Reconstruction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine In Press

Liney GP, Knowles AJ, Manton DJ, Turnbull LW, Blackband SJ, Horsman A (1996) Comparison of conventional single echo and multi-echo sequences with a fast spin echo sequence for quantitative T2 mapping: Application to the prostate. J Magn Reson Imaging 6:603–607

Heule R, Bar P, Mirkes C, Scheffler K, Trattnig S, Bieri O (2014) Triple-echo steady-state T-2 relaxometry of the human brain at high to ultra-high fields. NMR Biomed 27:1037–1045

Heule R, Ganter C, Bieri O (2014) Triple Echo Steady-State (TESS) Relaxometry. Magn Reson Med 71:230–237

Santini F, Patil S, Scheffler K (2011) IceLuva: A Scripting Framework for MR Image Reconstruction Based on Free Software. Concepts Magn Reson Part B: Magn Reson Eng 39B:1–10

Mosher TJ, Smith H, Dardzinski BJ, Schmithorst VJ, Smith MB (2001) MR Imaging and T2 mapping of femoral cartilage: In vivo determination of the magic angle efect. Am J Roentgenol 177:665–669

Nishii T, Kuroda K, Matsuoka Y, Sahara T, Yoshikawa H (2008) Change in knee cartilage T2 in response to mechanical loading. J Magn Reson Imaging 28:175–180

Mamisch TC, Trattnig S, Quirbach S, Marlovits S, White LM, Welsch GH (2010) Quantitative T2 mapping of knee cartilage: differentiation of healthy control cartilage and cartilage repair tissue in the knee with unloading--initial results. Radiology 254:818–826

Liess C, Lusse S, Karger N, Heller M, Gluer CC (2002) Detection of changes in cartilage water content using MRI T2-mapping in vivo. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 10:907–913

Nieminen MT, Rieppo J, Toyras J et al (2001) T2 relaxation reveals spatial collagen architecture in articular cartilage: a comparative quantitative MRI and polarized light microscopic study. Magn Reson Med 46:487–493

Kurkijarvi JE, Nissi MJ, Kiviranta I, Jurvelin JS, Nieminen MT (2004) Delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage (dGEMRIC) and T2 characteristics of human knee articular cartilage: topographical variation and relationships to mechanical properties. Magn Reson Med 52:41–46

Juras V, Bittsansky M, Majdisova Z et al (2009) In vitro determination of biomechanical properties of human articular cartilage in osteoarthritis using multi-parametric MRI. J Magn Reson 197:40–47

Poole AR, Kojima T, Yasuda T, Mwale F, Kobayashi M, Laverty S (2001) Composition and structure of articular cartilage: a template for tissue repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res:S26-33

Juras V, Welsch GH, Millington S et al (2009) Kinematic biomechanical assessment of human articular cartilage transplants in the knee using 3-T MRI: an in vivo reproducibility study. Eur Radiol 19:1246–1252

Trattnig S, Mamisch TC, Welsch GH et al (2007) Quantitative T2 mapping of matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte transplantation at 3 Tesla: an in vivo cross-sectional study. Invest Radiol 42:442–448

White LM, Sussman MS, Hurtig M, Probyn L, Tomlinson G, Kandel R (2006) Cartilage T2 assessment: differentiation of normal hyaline cartilage and reparative tissue after arthroscopic cartilage repair in equine subjects. Radiology 241:407–414

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Prof. Siegfried Trattnig, MD. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. This study has received funding by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) P 25246 B24 and Slovak Grant Agency APVV-0431-12. One of the authors has significant statistical expertise. Institutional review board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (patients) in this study. Methodology: prospective, cross sectional study, performed at one institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Juras, V., Bohndorf, K., Heule, R. et al. A comparison of multi-echo spin-echo and triple-echo steady-state T2 mapping for in vivo evaluation of articular cartilage. Eur Radiol 26, 1905–1912 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3979-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3979-6