Abstract

General Joint Hypermobility (GJH) is a common condition found in 2–57% of the population. Of those with GJH, 10% suffer from accompanying physical and/or psychological symptoms. While the understanding of GJH in the general population is unfolding, its implication in a cohort of children, adolescents and young adults are not yet understood. This systematic review explored GJH’s prevalence, tools to measure it, its physical and psychosocial symptoms, with a special interest in aesthetic sports. The CINHAL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus and Scopus databases were searched for relevant studies. Inclusion criteria were (1) Age range of 5–24; (2) Participants had GJH; (3) A measurement for GJH; (4) Studies written in English language. Study screening for title, abstract and full text (when needed) and quality assessment were performed by two independent individuals. 107 studies were included in this review and were thematically grouped into six clusters expressing different foci: (1) GJH’s Core Characteristics; (2) Orthopedic; (3) Physical Other; (4) Psychosocial; (5) Treatment and (6) Aesthetic Sports. The review revealed a growing interest in GJH in this cohort in the last decade, especially regarding non-musculoskeletal physical implications and psychosocial aspects. Prevalence varied between different ethnic groups and as a parameter of age, gender and measurement. The most widespread tool to measure GJH was the Beighton scale, with a cut-off varying between 4 and 7. Children show fewer, but similar GJH implication to those in the general population, however, more research on the topic is warranted, especially regarding psychosocial aspects and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This systematic review of empirical research focuses on the health and psychological symptoms related to hypermobility in children, adolescents, and young adults. The term hypermobility is defined as increased Range of Motion (ROM) in the joints, considering age, gender, and ethnicity [1]. While such ROM can be acquired, this study’s interest lies in heritable hypermobility, which is a Heritable Disorder of Connective Tissue (HDCT). HDCTs are a group of 200 genetic disorders affecting connective tissue matrix protein, leading to structural, functional, and biomechanical abnormalities that can manifest in tissue fragility and malfunction and can be difficult to diagnose [1, 2]. The most common of the HDCTs, are Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders (HSD) and in particular, Joint Hypermobility (JH). JH is a Heritable Spectrum of four Disorders (HSD) [3], Localized JH, Generalized JH, Peripheral JH, and Historical JH. Within HSD, Generalized JH (GJH) is the most prominent and common and has clear criteria for clinical observation; accordingly, GJH was the focus of this review. GJH presents in a general display (involving the whole body) occurring in 2–57% of the population [4]. Of those with GJH, 10% suffer from physical and/or psychological symptoms with 0.5–2% estimated prevalence [5]. It can present as symptomatic or asymptomatic and is widely measured by the Beighton Scale (BS) [6]. The BS is an observational tool considered the most reliable and valid for measuring JH in both pediatric and adult populations, to date. However, it was recently advised to use it carefully, especially in children, where its validity is unclear [7].

As the research field is still emerging and the classifications of JH have changed with new guidelines coming out in 2017, the present study, therefore, aimed to examine GJH’s operationalization and trends in research over the years. Another caveat rising from the literature, is the scope of GJH in a younger population of children, adolescents, and young adults, who present different symptoms, for the most part, less debilitating than adults [8]. Consequently, this study explored GJH’s physical implications in this particular population. It identified different tools used to screen for GJH and determined its prevalence in children and adolescents. Moreover, it aimed to identify psychosocial implications of GJH in youth, including quality of life and mental health disorders with a view to highlight areas that require further research regarding GJH’s psychosocial aspects in this cohort. The review also focused on aesthetic sports and dance contexts, as it has been suggested that there are special considerations for people with hypermobility engaging in these activities, such as the need for different measurements as well as advantages and disadvantages it can pose [9].

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic review was performed by electronic searches on April 11th, 2023 in CINAHL (n = 136), SPORTDiscus (n = 37), PsycINFO (n = 64), MEDLINE (n = 141), and Scopus (n = 230). Previous hypermobility systematic reviews were screened and the searches were trialed and refined. In each of the five databases, the following search terms were used in the title field (hypermobility or “joint hypermobility” or “general joint hypermobility” or “joint hypermobility syndrome” or “benign joint hypermobility syndrome” or hyperlaxity or “joint laxity” or “joint flexibility” or “hypermobile spectrum disorders” or “connective tissue disorders” or “collagen abnormalities”) AND (child or children or teen* or teenager* or student* or undergraduate* or youth or “young people” or “young adult” or pediatric). See Fig. 1 for selection process.

Study selection

This systematic review followed the PRISMA statement guidelines [10], and was guided by the PICOS method for the search strategy: Participants (children, adolescents, and young adults with and without GJH, between the age of 5 and 24), Intervention (presence of GJH), Comparison (healthy controls), Outcomes (tools for measuring GJH, prevalence of GJH, physical and psychological implications of GJH), and Study design (any study where data was obtained). The review protocol was submitted in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=259272).

Selection criteria

Included articles had to meet the following criteria: (1) participants were children, adolescents or young adults aged 5–24 years; (2) participants had GJH; (3) there was a clinical assessment method to classify GJH; and (4) the study was reported in English. Studies were excluded if: (1) participants were younger than 5 years old or older than 24; (2) participants did not have GJH; (3) the studies had no clear measurement for GJH; or (4) the studies were commentaries or reviews.

Data extraction

Two of the authors independently screened titles and abstracts for relevant studies. Any conflicts were resolved in a discussion with the full paper retrieved for further assessment when necessary, and consensus was achieved. Handling of data was done through Covidence, for easy screening and data extraction.

Main outcome variables

This study was interested in childhood GJH including prevalence, tools to measure it, and its physical as well as psychosocial symptoms.

Risk of bias assessment

Quality assessment was rated independently by two authors using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies [11]. Any conflicts were resolved by discussion. EPHPP addresses selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection, and withdrawals. A study’s global rating can range between: ‘strong’ = no weak subscale ratings; ‘moderate’ = one weak subscale rating; and ‘weak’ = two or more weak subscale ratings.

Analysis

This review used a narrative synthesis.

Results

The electronic database search identified 608 articles. After removal of duplicates, 255 studies were screened for title, abstract, and full text, when needed. One hundred and seven studies met inclusion criteria and were included in the current review. Fifty-four studies were rated “weak”, fifty-one were rated “moderate”, and two were rated “strong”. This was mostly due to weaker study designs, with 78 cross-sectional studies (see Table 1).

The papers in this review were thematically grouped into six clusters expressing different foci: (1) GJH core characteristics; (2) orthopedic; (3) physical other; (4) psychosocial; (5) treatment, and (6) aesthetic sports (see Table 2). Twelve studies fit into more than one category (e.g., a prevalence study examining orthopedic problems) and were included in both.

Synthesis of findings by theme

GJH characteristics

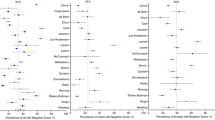

First, this cluster includes studies exploring prevalence of GJH in specific populations, such as children of various ages from ten different countries (see Table 3(1:A)).

The prevalence of GJH in different ethnic groups ranged between 9.4% (with a BS cut-off of ≥ 4) [56] and 36% (with a Carter–Wilkinson criteria cut-off of > 5) [52]. Most studies found higher prevalence of GJH in younger children [51, 52, 105, 118]. Findings regarding gender differences were inconsistent. Whereas most studies found GJH was more prevalent in girls [16, 30, 54, 56, 61, 103, 119], in others it was just a trend [41, 52, 99, 105, 117]. One study found a higher prevalence in boys [118] and one study found a higher prevalence in boys aged 6–10, while prevalence was higher in girls aged 11–15 and overall [108], and two studies found no gender differences [25, 94].

Studies also investigated the prevalence of GJH in association with musculoskeletal conditions such as scoliosis or pain, showing no links with scoliosis [25, 40, 56, 94]. One study observing GJH and fibromyalgia found no correlation between them, with only one child meeting criteria for both conditions [16]. A different study looked at GJH’s prevalence in children with gastrointestinal problems, finding no association between these conditions [104]. Another study examined the prevalence of GJH in patients with vesicoureteric reflux and found that 66.7% of boys and 57.7% of girls had GJH, indicating links between these conditions as its prevalence in this cohort was much higher than in the general population [110]. Two studies looked at GJH’s prevalence in Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), with one study finding correlations between symptomatic GJH and POTS and the other finding no such correlation with GJH [24, 113]. Another study observed the prevalence of GJH in children with anxiety [91] and found it was higher in comparison to children without anxiety (see Table 3(1:B)).

One study in this cluster looked at Body Mass Index (BMI) and GJH and found they were negatively correlated, so that underweight children had a higher percentage of GJH [98]. Another study examining GJH’s importance in pre-pubertal children found more joint pain in children with GJH, which correlated with parents’ musculoskeletal problems, and higher frequency of flat feet than in healthy comparisons [116]. Two studies looked at general signs and symptoms of GJH and classified children into subcategories with possible different complications and trajectories. The first ran a multifactorial analysis, identifying five distinct GJH clusters [89]. The second study was longitudinal, following children for 3 years. It identified three subgroups according to symptom severity [100]. Functional impairment at baseline was predictive of reduced walking distance and decreased quality of life. Four underlying constructs contributed to disability: multi-systemic affects, pain, fatigue, and loss of postural control.

The final type of studies in this cluster assessed screening tools for GJH. Out of the six articles included in this review, five used the BS. The earliest study examined BS’s validity in children, deeming it valid [106]. The second study looked at inter-test reliability of two different BS versions and found moderate to substantial reproducibility for both methods, when following standardized protocols [63]. Another study compared the BS with the Hospital del Mar criteria, and found more children had GJH using the latter than a cut-off of ≥ 4 on the former with a prevalence of 34% versus 12%, respectively [84]. The fourth study examined BS’s suitability for children with intellectual disability. Agreement between judges was moderate and inter-class correlations yielded excellent reliability. GJH’s prevalence in this population was similar to children without intellectual disabilities (8%), with correlations between GJH and age and gender, suggesting its usage was feasible and reliable in this cohort [92]. The fifth study looked at reproducibility of GJH assessment online versus in-person, showing that while more children were classified as having GJH in the in-person mode, agreement on BS score was fair to excellent. Tools measuring upper limb and lower limb hypermobility yielded much poorer agreements [59]. The final study on screening methods investigated whether functional tests of the pelvic-hip complex and trunk flexibility could screen for GJH. There was no difference in functional tests between children with and without GJH (as measured by the BS), indicating this was not a valid tool for screening GJH [31].

Orthopedic implications of GJH

The orthopedic cluster is the largest cluster in this review, covering topics such as certain joints and their biomechanics, gait patterns, joint pain, and injuries. Joints of interest included the spine and scoliosis, knees, hips, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and clicking and more (see Table 3(2:A)).

Studies in this cluster also examined various orthopedic implications. Findings regarding motor competence in children and adolescents were inconsistent. Two studies showed a decrease in muscle strength, with an impairment in exercise capacity [14, 57]. A study looking at GJH in typically developing children and children with motor developmental impairments revealed some differences in GJH between the groups. However, GJH failed to explain differences in variance beyond neuromuscular performance, indicating no association between motor performance development and GJH [115]. Two studies showed the reversed link, where children with GJH performed better than their healthy counterparts. One of the studies reported girls with GJH performed better in vertical height jump [94], with the other showing children with GJH had better dynamic balance and shorter reaction times than those without GJH [66].

The two studies looking at developmental coordination disorders (DCD) found no difference in DCD among children with and without GJH [75], with a tendency of children with GJH to score higher in dexterity than children without [37].

Studies examining gait in youth with GJH showed gait pattern differences between them and healthy controls. One study found differences in kinetics, lower peak joint moments, and smaller step width in children with GJH [82]. A second study showed knee movement patterns significantly differed in children with and without GJH [49]. A third paper found that children with GJH had decreased lateral trunk stability accompanied by decreased head stability while walking compared to controls [47].

Studies looking at arthralgia, musculoskeletal pain, and injuries in GJH found some associations between them. The first study reported 17.6% of participants had Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) [94]. Several studies found a significantly higher occurrence of musculoskeletal pain and arthralgia in children with GJH compared to those without and one study found that children with EDS had higher pain intensity, more discomfort and worse life quality than controls [12, 14, 25, 50, 76]. In contrast, one study found GJH was only related to worse pain in children who reported any pain [109], while two studies found no association between GJH and widespread pain [66, 94]. Most common musculoskeletal complaints in children with GJH were ankle sprains (31.3%), exercise-related pain (15%), arthralgia (12.6%), and back pain (10.6%) [12, 25]. Regarding injuries, results were conflicting, with one study finding higher prevalence of dislocations/subluxations in children with GJH compared to controls, another study finding a higher BS was associated with an increased risk of injury, but not with injury severity, while a third study did not find more injuries in the GJH group [66, 93, 94] (see Table 3(2:B)). Two follow-up studies found that while GJH in childhood increased the risk for developing musculoskeletal pain in adolescence, it did not affect physical functioning, daily activities or participation in them [107, 109]. Three studies examined proprioception in GJH, showing conflicting results. While two studies found reduced proprioception in children with GJH [15, 48], another study found no differences regarding proprioceptive acuity between children with and without GJH [48, 87].

Other physical implications

While GJH’s most common implications are joint and musculoskeletal system involvement, it has other physical implications. Three studies examined gastrointestinal problems. Whereas the first study found children with functional nausea and vomiting disorders had more GJH [86], the second study showed no correlation between GJH and gastrointestinal involvement [104]. A third study looked at the interlinks between GJH and fibromyalgia in children with gastrointestinal disorders and suggested all three conditions were interlinked, perhaps through emotional distress, as presence of GJH and fibromyalgia in this cohort was rather high (32.5% and 64.2%, respectively) [96].

Three studies found no association between the autonomic system and GJH, with no links between GJH and orthostatic hypotension, tolerance, and POTS, and a trend toward more dizziness in the GJH group [29, 112, 113], while one study showed that among children with POTS, 61.7% had symptomatic GJH, indicating a link between these conditions [24]. Some links were found between central sensitization and GJH. One study showed GJH was associated with more hyperalgesia and lower pain threshold. BS scores were also correlated with central sensitization and functional disability [20]. A second study found that although adolescents with GJH had higher comorbidity with chronic pain and functional disability, this was only true for a subjective pain level assessment [19]. Two studies explored GJH’s relation to the reproductive system. The first observed hormone levels, finding that higher levels of sex‐hormone‐binding globulin serum in both genders were associated with a greater number of hypermobile joints [55]. The other study focused on heavy menstrual bleeding, finding that 80% of young women reported heavy menstrual bleeding, 70% reported menses interfering with work and social life, and 87% reported limitations in physical activity [69].

Three studies examining urinary problems, voiding dysfunction and vesicoureteric reflux found a significant bi-directional association with GJH [38, 67, 110]. Patterns for boys and girls were different—boys showed more constipation problems, whereas girls showed more incontinence and urinary tract infections[38].

Two studies that observed bleeding symptoms in relation to GJH showed that patients had much higher abnormal bleeding symptoms than their prevalence in the general population [58, 70], with the most common bleeding in the cohort being oral bleeding (74.1%), easy bruising (59.3%), and bleeding with minor wounds (42.0%) [70]. It was also found that 28% of hemostasis patients had GJH and 15.6% had EDS [58].

One study looking at eye care in children with GJH found no significant differences between children with and without GJH regarding biomechanical and topographic parameters and no increased risk of keratoconus in children with GJH [18].

One study looking at dental status in children with GJH found higher prevalence of plaque and tooth bleeding in the GJH group compared to control group, while there was no difference in decay, tooth filling, and missing teeth, as well as in tooth mobility [39].

Three studies examined the link between GJH and chronic illness. Two of which looked at fibromyalgia, with one showing no association between the two conditions, while the other suggested they might have underlying pathways [16, 96]. A study looking at children with and without Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) found significantly higher BS scores in CFS patients [17] (see Table 3(3)).

Three papers compared three groups: children with symptomatic GJH; children with asymptomatic GJH; and healthy children. Children with symptomatic GJH had significantly higher total ROM, skin extensibility and lower bone density, lower diastolic blood pressure, and higher degradation products in urine compared to children with asymptomatic GJH. When compared with healthy controls, children with asymptomatic GJH had higher total ROM and more skin extensibility [42]. Decreased absolute peak and relative oxygen consumption were found in both patient groups, indicating lower exercise tolerance [43]. The third study found higher pain intensity in children with symptomatic compared to asymptomatic GJH. Differences also emerged in balance and activity and children with symptomatic GJH required more rest than healthy children [102].

Psychosocial implications

The psychosocial implications of GJH on children and adolescents’ cluster included studies with three different foci: (1) mental health disorders; (2) life quality and functioning; (3) neurodevelopmental disorders. Three papers studied Anxiety Disorders (AD), finding a significant bi-directional correlation with GJH [26, 91]. The most prevalent ADs in this cohort were separation anxiety, social phobia, and fears of physical injury [45]. One study looked at Eating Disorders (ED) and found GJH had a weak significant link with reported disordered eating [27]. Seven studies focused on quality of life and found it was lower in youth with GJH in comparison to healthy controls. Pain along with number of symptoms, fatigue, and stress incontinence predicted quality of life, dysfunction, anxiety, and depression in the GJH group [21, 22, 50, 78, 90]. Children and adolescents with EDS reported their greatest challenges were managing their physical symptoms, not being able to do things their peers do and feeling left out [21, 111]. Social support did not mitigate the negative impact EDS had on quality of life or mental health [22]. Only one study showed no association between GJH and quality of life [101]. Two studies explored neurodevelopmental disorders in children and adolescents with GJH. Whereas one found GJH was not associated with learning disabilities [36], a newer study found that both Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) were higher in the GJH group than in the general population [71].

Treatments

This cluster included three types of treatments: interventions, rehabilitation, and orthopedic aids for children with GJH. Five studies offered patients physical interventions, which included either physiotherapy, strengthening, and movement training or a combination, often accompanied by education about GJH. All studies found improvement in pain, injury, and/or strength post-intervention [23, 56, 79]. One study compared knee strengthening exercises either in full ROM or only in a non-hyperextended ROM for children with GJH. It showed both groups had significant improvements post compared to pre-interventions; however, overall, working at a hyperextended range was more beneficial, especially for self-esteem, behavior, and mental health [88]. One study showed that ride therapy was favorable to therapeutic gymnastics in increasing muscle strength, proprioception, and knee stability [77]. A study conducting an interdisciplinary intervention, combining physical therapy, psychological counseling, and occupational therapy, showed improvements in pain, physical functioning, and mental health [95] (See Table 3(5)). Another study treated children with hypermobility and an overactive bladder using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. It found 77% of the children had complete to mild improvement in incontinence symptoms, while only 23% showed no improvement [97].

Two studies were case studies looking to rehabilitate children with a specific complaint and underlying GJH, both offered a strengthening and stability training program and reported patients’ full recovery [68, 79].

Two studies explored orthopedic aids for treating GJH’s implications. A paper looking at Neoprene wrist/hand splints found they were not beneficial in reducing pain or improving children with GJH’s handwriting [53]. However, a study examining effects of foot orthotics on gait patterns in children with GJH demonstrated improvements in gait synchrony, and less step variability [74].

Aesthetic sports

This cluster included only three studies. The first study observed differences in spine curvatures of ballet students in comparison to age-matched non-dancers. It found significant differences between the groups for all spine mobility variables except total ROM in the lumbar spine. Moreover, kyphosis and lordosis were less prominent in ballet dancers [83]. Another study examining difference between dancers and non-dancers with GJH found dancers reported less pain, fewer pain-related problems, and less body areas affected by pain. Furthermore, dancers perceived school functioning, sleep/rest, cognitive, and total fatigue levels as better [80]. A study looking at GJH in elite athletes found the highest prevalence of GJH in ballet and TeamGym. These disciplines also showed the lowest life quality. There was no difference between athletes with and without GJH in neither life quality, muscle strength nor in injuries [101].

Mapping changes in the field

This review identified changes that occurred in the research field throughout the years. First, there has been growth in the volume of GJH studies in children and adolescents in recent years. While research began in the 1980s, publications were sporadic until the second decade of the twenty-first century. Frequency increased since 2011, with 2020 being publications’ peak year (see Fig. 2).

Second, a change in the studies’ foci was identified. Early papers mostly belonged to either the GJH core characteristics or the orthopedic cluster. Most studies in the physical cluster came out in the second decade of the twenty-first century. Some newer studies incorporate a biopsychosocial approach, examining quality of life, with the first study published in 2011 and the first mental health disorders associated with GJH study published in 2018 (see Fig. 2).

Discussion

This review aimed to synthesize and evaluate evidence of the prevalence of GJH among children, adolescents, and young adults, and how it is measured. The review also examined evidence of GJH’s physical and psychosocial implications in this cohort, along with GJH in a context of aesthetic sports. The review included 107 studies that fell into 6 thematic clusters, with a large body of research regarding core characteristics of GJH and its physical and especially musculoskeletal implications. Very few studies, all published in the last decade, examined GJH’s psychosocial implications, with even fewer looking at GJH in aesthetic sports. Another type of studies identified and included was treatments for GJH’s symptoms. The review also identified changes and trends in the field over time.

Prevalence

The prevalence of GJH in different studies ranged between 9 and 36% [52, 56], similar to reports in the general population (2–57%) [4]. Prevalence differences are explained by age, gender, ethnicity, activity, and measurement. Indeed, this review found age was negatively correlated with GJH, with less GJH in older children [41, 52]. Most studies included in the review found that girls had higher prevalence of GJH, while some failed to show gender differences. This is possibly due to papers examining pre-pubertal children who show no such differences. This is supported by Forelo et al.’s study [52] that found no gender differences in younger children, with significant differences in adolescents.

In terms of measuring GJH, studies employing the BS deemed it a suitable tool for children, including those with intellectual disabilities, when following a standardized protocol and a cut-off of ≥ 5 [63, 92, 106]. However, even within the current review, prevalence studies suggested cut-off points, ranging between 4 and 7. Recent papers on the BS argue that it lacks standardization, has an unclear administration procedure, and measures joints not necessarily indicative of GJH [7]. Hence, more studies are warranted to investigate BS’s validity.

While some older studies used tools such as the Carter–Wilkinson criteria, almost all studies conducted in the twenty-first century used the BS. In several studies, participants were also tested for EDS; however, unlike GJH’s screening, EDS must be diagnosed by a clinician, making it harder to utilize in multidisciplinary research. In practice, some other physical markers are used (e.g., skin markers, anthropometrics); however, this review found no evidence of their usage in research.

Physical implications

The understanding of GJH as a condition affecting not only the joints, but other areas of the body is rather new. This might explain why more recent studies included in this review looked at other physical implications of GJH. While some of GJH’s accompanying symptoms are local, others are global and systematic with studies exploring both types of manifestations [8]. Findings regarding the gastrointestinal and autonomic systems were in contrast to well-established links in adults, as several studies in this review found no differences in youth with GJH [120]. One possible explanation is that the studies did not differentiate between symptomatic and asymptomatic GJH, this is supported by the single study that looked at symptomatic GJH in children with POTS and found it was highly prevalent in this cohort [24]. However, it is unlikely, as other differences such as higher somatization and depression were observed in the studies that failed to find links between GJH and autonomic and gastrointestinal system involvement [104]. Authors suggested these findings could indicate real differences between adults and children, or limitations of the studies due to tools that lack sensitivity, or selection bias [112]. More research is needed to resolve these discrepancies.

Compatible with research on adults [3], central sensitization was linked with GJH, with higher hyperalgesia and a lower pain threshold in children and adolescents [19, 20].

Studies looking at gynecologic implication showed most females with GJH reported heavy menstrual bleeding [69]. These finding are consistent with gynecological problems in adult women [121]. Urinary and voiding dysfunction, which showed links with GJH in this review, have shown similar associations in adults and especially in woman, who suffer from urinary tract dysfunction, bladder problems, and prolapses [122].

Psychosocial implications

Studies observing psychosocial aspects of GJH are becoming more common and suggest such links might involve pathophysiological pathways [123]. Compared to the volume of studies examining GJH’s psychosocial implication in adults, those are still scarce in young people. Most psychosocial studies in this review focused on quality of life, with only four looking at mental health disorders. Furthermore, only anxiety and eating behaviors were examined in this cohort, while adult studies have tackled many more mental health disorders [2].

Studies on anxiety found GJH and anxiety had a similar bi-directional link to that seen in adults with a higher prevalence of GJH in people with anxiety, as well as a higher prevalence of anxiety in people with GJH than in those without [2, 26, 91, 123]. However, specific ADs in adults with GJH are different from those found in children [124], sharing only social phobia in both populations [45]. Separation anxiety might be linked with GJH only in children, as it mostly manifests in childhood. It might stem from parents of children with GJH seeing them as weaker and requiring more care. This parenting style could, in turn, lead to separation anxiety. Fears of injury could be explained due to children with GJH experiencing more pain, injuries, and medical encounters. However, more comprehensive studies are needed to better understand the mental health of children with GJH.

The study looking at EDs found a positive link between reported disordered eating and BS scores [27]. However, only four participants in the study met the criteria for an ED. Previous studies did show links between GJH and EDs [125].

Studies on quality of life in youth with GJH found a significant decrease in their life quality and increased dysfunction. These were linked to pain, anxiety, incontinence, and fatigue. Findings in adults with GJH also showed decreased life quality and disability [126]. Further research is required to determine the full extent of the impairment and hardships this cohort experiences.

In the current review, only two papers looked at learning difficulties in children with GJH, with conflicting findings. While one study reported no such link [36], the second found both ADHD and ASD were associated with GJH. Previous studies found links between ADHD, ASD, and GJH, and suggested common pathways, including DCD, fatigue, and sensory anomalies [125, 127].

Interventions

All treatments included in this review showed improvements post-intervention for youth with GJH compared to pre-intervention, apart from a study about wrist/hand splints. Physiotherapy, strengthening and stability exercises, psychological counseling, occupational therapy, and ride therapy were able to decrease pain, improve strength, life quality and specific orthopedic problems. Only a few studies tackled interventions for people with symptomatic GJH, with inconclusive results [128]. The existing literature recommends encompassing interventions, targeting both physical and psychosocial aspects [8]. However, most interventions are local, focusing on symptoms, instead of targeting the root of the problem. More research on this topic is needed.

Aesthetic sports

Studies on dancers with GJH reported fewer back problems, better school functioning, better sleep/rest, and less fatigue and pain in comparison to non-dancers with GJH [80, 83]. Studies comparing well-being and functioning of dancer and non-dancer adults with GJH, found that while dancers had higher muscle strength and performed better on functional tests, they reported more fatigue and pain than non-dancers [129]. Pain and fatigue might increase in those with GJH later in life, accounting for such discrepancies. A third study found that within a group of elite athletes, dancers and gymnasts had the highest prevalence of GJH, which is consistent with findings in collegiate dancers [129]. Dancers and gymnast also reported the lowest quality of life, a finding compatible with results in adults [101]. Studies regarding aesthetic sports/dance are scarce across all populations and the interlinks between them and GJH should be further investigated.

Trends in the literature

This review revealed trends in research—notably, the volume of studies on childhood and adolescence GJH has increased in the last decade. Perhaps due to the growing understanding of the implications and trajectory of GJH, alongside the understanding that early interventions could help prevent its symptoms from worsening [3]. So far, 2020 has been the peak year for number of publications, closely followed by 2022, indicating a growing interest in the research field.

The recent increase in the studies’ volume does not necessarily reflect their quality. Most studies included in this review were cross-sectional. Whereas some studies were more comprehensive, recruiting large samples, allowing follow-ups and performing clinical exams, those were rare. Some newer studies still lack rigorous and robust methods, with many recruiting small, convenience samples, and only screening for GJH using the BS. Another problem that arose was the lack of coherent terminology. Although 2017 accelerated a shift toward new taxonomy, not all researchers have adopted it, creating confusion around terms referring to symptomatic GJH.

Changes were also observed in the focus of the research field throughout the years. From focusing on prevalence and musculoskeletal problems, the range expanded to include other physical implications (e.g., gastrointestinal and cardiovascular involvement), and a psychosocial perspective, looking at life quality and mental health. It can be argued these changes reflect the growing understanding regarding GJH in the general population as a global condition, affecting the entire body as well as the mind [123]. Moreover, it is likely to reflect a shift in the medical field to the biopsychosocial model, looking at aspects of patients’ lives other than biological ones [130].

Limitations

This review’s limitations arise from the large number of studies included, which restricted examining the implications of GJH in detail, while only outlining a wider understanding of it in children and adolescents. Moreover, studies included were mostly of low methodological quality; hence, results should be observed with caution. Some topics in this review included only one or two studies, so it is harder to draw conclusions on them. Furthermore, this study did not include HCTDs other than GJH and EDS, which limited its scope.

Conclusion

The current review included 107 studies exploring GJH in children, adolescents, and young adults. It examined GJH’s prevalence in this population, tools used to measure it, its physical along with psychosocial implications, treatments to improve its debilitating effects and GJH in an aesthetic sports context. The review found a growing interest in GJH in this cohort, especially regarding non-musculoskeletal physical implications and psychosocial aspects. Prevalence varied between different ethnic groups and as a function of age, gender, and measurement. BS was the most widespread tool to measure GJH. While links with many physical conditions emerged, these seem fewer than in an adult population. Psychosocial implications and decreased quality of life resembled findings in adults. The proposed interventions helped ease many impeding symptoms; however, further research is warranted to determine the full scope of GJH’s impairment in childhood, especially regarding the psychosocial aspects, as well as effective treatments.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

References

Tinkle BT (2020) Symptomatic joint hypermobility. Best Practice Res Clin Rheumatol 34(3):101508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.berh.2020.101508

Baeza-Velasco C, Pailhez G, Bulbena A, Baghdadli A (2015) Joint hypermobility and the heritable disorders of connective tissue: clinical and empirical evidence of links with psychiatry. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 37(1):24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.10.002

Castori M, Tinkle B, Levy H, Grahame R, Malfait F, Hakim A (2017) A framework for the classification of joint hypermobility and related conditions. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 175(1):148–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31539

Remvig L, Jensen DV, Ward RC (2007) Epidemiology of general joint hypermobility and basis for the proposed criteria for benign joint hypermobility syndrome: review of the literature. J Rheumatol 34(4):804–809

Hakim AJ, Sahota A (2006) Joint hypermobility and skin elasticity: the hereditary disorders of connective tissue. Clin Dermatol 24(6):521–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.07.013

Beighton PH, Solomon L, Soskolne CL (1973) Articular mobility in an African population. Ann Rheum Dis 32(5):413. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.32.5.413

Malek S, Reinhold EJ, Pearce GS (2021) The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatol Int 41(10):1707–1716. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-021-04832-4

Tinkle B, Castori M, Berglund B, Cohen H, Grahame R, Kazkaz H, Levy H (2017) Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (aka Ehlers-Danlos syndrome Type III and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type): clinical description and natural history. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet 175(1):48–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31538

Foley EC, Bird HA (2013) Hypermobility in dance: asset, not liability. Clin Rheumatol 32(4):455–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2191-9

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group* (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Internal Med 151(4):264–269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies (2010). Eff Public Heal Pract Proj McMaster Univ Toronto 20(1998):1–4

Abujam B, Aggarwal A (2014) Hypermobility is related with musculoskeletal pain in Indian school-children. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32(4):610–613

Akalan E, Apti A, Kurt RA, Sert R, Önerge K, Leblebici G, et al (2018) The infulence on hypermobility on children with increased femoral anteversion: static and dynamic foot pressure behavior

Akkaya KU, Burak M, Erturan S, Yildiz R, Yildiz A, Elbasan B (2022) An investigation of body awareness, fatigue, physical fitness, and musculoskeletal problems in young adults with hypermobility spectrum disorder. Musculoskelet Sci Practice. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2022.102642

Akkaya KU, Burak M, Yildiz R, Yildiz A, Elbasan B (2023) Examination of foot sensations in children with generalized joint hypermobility. Early Hum Develop. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2023.105755

Barcak O, Karkucak M, Capkin E, Karagüzel G, Dilber B, Dedeoglu S (2015) Prevalence of generalized joint hypermobility and fibromyalgia syndrome in the children population of Trabzon: a Turkish study. Turkiye Fiziksel Tip Ve Rehabilitasyon Dergisi-Turk J Phys Med Rehabilit. https://doi.org/10.5152/tftrd.2015.6500

Barron DF, Cohen BA, Geraghty MT, Violand R, Rowe PC (2002) Joint hypermobility is more common in children with chronic fatigue syndrome than in healthy controls. J Pediatr 141(3):421–425. https://doi.org/10.1067/mpd.2002.127496

Bayramoğlu SE, Sayın N, Ekinci DY, Ayaz NA, Çakan M (2020) Anterior segment analysis and evaluation of corneal biomechanical properties in children with joint hypermobility. Turk J Ophthalmol 50(2):71. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjo.galenos.2019.28000

Bettini EA, Moore K, Wang Y, Hinds PS, Finkel JC (2018) Association between pain sensitivity, central sensitization, and functional disability in adolescents with joint hypermobility. J Pediatr Nurs 42:34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.06.007

Bettini EA (2016) Central sensitization and associated factors in adolescents with joint hypermobility and dysautonomia. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Arizona

Bieniak KH, Koven ML, Bedree H, Tinkle BT, Tran ST (2022) Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: Caregiver-child concordance across challenges, readiness to change, and coping. Clin Practice Pediatr Psychol 10(2):139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000411

Bieniak KH, Tinkle BT, Tran ST (2022) The role of functional disability and social support in psychological outcomes for individuals with pediatric hypermobile ehlers–danlos syndrome. J Child Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1177/13674935221143822

Birt L, Pfeil M, MacGregor A, Armon K, Poland F (2014) Adherence to home physiotherapy treatment in children and young people with joint hypermobility: a qualitative report of family perspectives on acceptability and efficacy. Musculoskelet Care 12(1):56–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1055

Boris JR, Bernadzikowski T (2020) Prevalence of joint hypermobility syndromes in pediatric postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. Autonomic Neurosci-Basic Clin 231:102770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2020.102770

Bozkurt S, Kayalar G, Tezel N, Güler T, Kesikburun B, Denizli M et al (2019) Hypermobility frequency in school children: relationship with idiopathic scoliosis, age, sex and musculoskeletal problems. Arch Rheumatol 34(3):268. https://doi.org/10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2019.7181

Bulbena-Cabre A, Duñó L, Almeda S, Batlle S, Camprodon-Rosanas E, Martín-Lopez LM, Bulbena A (2019) Joint hypermobility is a marker for anxiety in children. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition) 12(2):68–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2019.05.001

Can S, Tuna F (2022) The impact of generalized joint hypermobility on eating behavior of students: a case–control study. J Am College Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2037613

Carr AJ, Jefferson RJ, Benson MK (1993) Joint laxity and hip rotation in normal children and in those with congenital dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 75(1):76–78. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.75B1.8421041

Chelimsky G, Kovacic K, Simpson P, Nugent M, Basel D, Banda J, Chelimsky T (2016) Benign joint hypermobility minimally impacts autonomic abnormalities in pediatric subjects with chronic functional pain disorders. J Pediatr 177:49–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.06.091

Clinch J, Deere K, Sayers A, Palmer S, Riddoch C, Tobias JH, Clark EM (2011) Epidemiology of generalized joint laxity (hypermobility) in fourteen-year-old children from the UK: a population-based evaluation. Arthritis Rheum 63(9):2819–2827. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30435

Czaprowski D, Kędra A, Pawłowska P, Kolwicz-Gańko A, Leszczewska J, Tyrakowski M (2015) The examination of the musculoskeletal system based only on the evaluation of pelvic-hip complex muscle and trunk flexibility may lead to failure to screen children for generalized joint hypermobility. PLoS ONE 10(3):e0121360. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121360

Czaprowski D, Pawłowska P (2013) The influence of generalized joint hypermobility on the sagittal profile of the spine in children aged 10–13 years. Ortopedia Traumatol Rehabilitacja 15(6):545–553. https://doi.org/10.5604/15093492.1091510

Czaprowski D, Pawłowska P, Kolwicz-Gańko A, Sitarski D, Kędra A (2017) The influence of the “straighten your back” command on the sagittal spinal curvatures in children with generalized joint hypermobility. BioMed Res Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9724021

Czaprowski D, Kotwicki T, Pawlowska P, Stolinski L (2012) Joint hypermobility syndrome in children with idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis 7(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-7161-7-S1-O69

Czaprowski D, Gwiazdowska-Czubak K, Tyrakowski M, Kedra A (2021) Sagittal body alignment in a sitting position in children is not affected by the generalized joint hypermobility. Sci Rep 11(1):13748. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93215-7

Davidovitch M, Tirosh E, Tal Y (1994) The relationship between joint hypermobility and neurodevelopmental attributes in elementary school children. J Child Neurol 9(4):417–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/088307389400900417

de Boer RM, van Vlimmeren LA, Scheper MC, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, Engelbert RH (2015) Is motor performance in 5.5-year-old children associated with the presence of generalized joint hypermobility? J Pediatr 167(3):694–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.06.034

de Kort LM, Verhulst JA, Engelbert RH, Uiterwaal CS, de Jong TP (2003) Lower urinary tract dysfunction in children with generalized hypermobility of joints. J Urol 170(5):1971–1974. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000091643.35118.d3

Demir F, Tüzüner T, Baygın Ö, Kalyoncu M (2021) Evaluation of dental status and temporomandibular joint in children with generalized joint hypermobility. JRC J Clin Rheumatol 27(8):e312–e316. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001356

Dobies-Krześniak BK, Werblińska A, Tarnacka B (2022) Joint hypermobility in school-aged children and adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis—a chance for more accurate screening? Ann Agric Environ Med 29(3):433–437. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/150010

El-Garf AK, Mahmoud GA, Mahgoub EH (1998) Hypermobility among Egyptian children: prevalence and features. J Rheumatol 25(5):1003–1005

Engelbert RH, Bank RA, Sakkers RJ, Helders PJ, Beemer FA, Uiterwaal CS (2003) Pediatric generalized joint hypermobility with and without musculoskeletal complaints: a localized or systemic disorder? Pediatrics 111(3):e248–e254. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.3.e248

Engelbert RH, van Bergen M, Henneken T, Helders PJ, Takken T (2006) Exercise tolerance in children and adolescents with musculoskeletal pain in joint hypermobility and joint hypomobility syndrome. Pediatrics 118(3):e690–e696. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2219

Evrendilek H (2019) Correlations between hypermobility, muscle strength and 3D gait parameters in children with increased femoral anteversion

Ezpeleta L, Navarro JB, De La Osa N, Penelo E, Bulbena A (2018) Joint hypermobility classes in 9-year-old children from the general population and anxiety symptoms. J Develop Behav Pediatr 39(6):481–488. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000577

Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB, Van Poortvliet JA, Phillips HUGH (1984) Influence of anthropometric factors and joint laxity in the incidence of adolescent back pain. Spine 9(5):461–464

Falkerslev S, Baagø C, Alkjær T, Remvig L, Halkjaer-Kristensen J, Larsen PK et al (2013) Dynamic balance during gait in children and adults with generalized joint hypermobility. Clin Biomech 28(3):318–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.01.006

Fatoye F, Palmer S, Macmillan F, Rowe P, van der Linden M (2009) Proprioception and muscle torque deficits in children with hypermobility syndrome. Rheumatology 48(2):152–157. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/ken435

Fatoye FA, Palmer S, Van der Linden ML, Rowe PJ, Macmillan F (2011) Gait kinematics and passive knee joint range of motion in children with hypermobility syndrome. Gait Posture 33(3):447–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2010.12.022

Fatoye F, Palmer S, Macmillan F, Rowe P, Van Der Linden M (2012) Pain intensity and quality of life perception in children with hypermobility syndrome. Rheumatol Int 32(5):1277–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1729-2

Fernandez-Bermejo E, Garcia-Jimenez MA, Fernandez-Palomeque C, Munuera L (1993) Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and joint laxity. A study with somatosensory evoked potentials. Spine 18(7):918–922. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199306000-00018

Forleo LH, Hilario MO, Peixoto AL, Naspitz C, Goldenberg J (1993) Articular hypermobility in school children in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Rheumatol 20(5):916–917

Frohlich L, Wesley A, Wallen M, Bundy A (2012) Effects of neoprene wrist/hand splints on handwriting for students with joint hypermobility syndrome: a single system design study. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 32(2):243–255. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2011.622035

Gocentas A, Jascaniniene N, Pasek M, Przybylski W, Matulyte E, Mieliauskaite D et al (2016) Prevalence of generalised joint hypermobility in school-aged children from east-central European region. Folia Morphol 75(1):48–52. https://doi.org/10.5603/FM.a2015.0065

Graf C, Schierz O, Steinke H, Körner A, Kiess W, Kratzsch J et al (2019) Sex hormones in association with general joint laxity and hypermobility in the temporomandibular joint in adolescents—results of the epidemiologic LIFE child study. J Oral Rehabilit 46(11):1023–1030. https://doi.org/10.1111/joor.12834

Gyldenkerne B, Iversen K, Roegind H, Fastrup D, Hall K, Remvig L (2007) Prevalence of general hypermobility in 12–13-year-old school children and impact of an intervention against injury and pain incidence. Adv Physiother 9(1):10–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14038190601103621

Hanewinkel-van Kleef YB, Helders PJ, Takken T, Engelbert RH (2009) Motor performance in children with generalized hypermobility: the influence of muscle strength and exercise capacity. Pediatric Phys Ther 21(2):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e3181a3ac5f

Hickey SE, Varga EA, Kerlin B (2016) Epidemiology of bleeding symptoms and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in paediatrics. Haemophilia 22(5):e490–e493. https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.13063

Hornsby EA, Tucker K, Johnston LM (2022) Reproducibility of hypermobility assessment scales for children when performed using telehealth versus in-person modes. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2022.2151393

Ilgunas A, Wänman A, Strömbäck M (2020) ‘I was cracking more than everyone else’: young adults’ daily life experiences of hypermobility and jaw disorders. Eur J Oral Sci 128(1):74–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/eos.12675

Jansson A, Saartok T, Werner S, Renström P (2004) General joint laxity in 1845 Swedish school children of different ages: age-and gender-specific distributions. Acta Paediatr 93(9):1202–1206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb02749.x

Jensen BR, Olesen AT, Pedersen MT, Kristensen JH, Remvig L, Simonsen EB, Juul-Kristensen B (2013) Effect of generalized joint hypermobility on knee function and muscle activation in children and adults. Muscle Nerve 48(5):762–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.23802

Junge T, Jespersen E, Wedderkopp N, Juul-Kristensen B (2013) Inter-tester reproducibility and inter-method agreement of two variations of the Beighton test for determining generalised joint hypermobility in primary school children. BMC Pediatr 13(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-13-214

Junge T, Larsen LR, Juul-Kristensen B, Wedderkopp N (2015) The extent and risk of knee injuries in children aged 9–14 with Generalised Joint Hypermobility and knee joint hypermobility-the CHAMPS-study Denmark. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 16(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-015-0611-5

Juul-Kristensen B, Hansen H, Simonsen EB, Alkjær T, Kristensen JH, Jensen BR, Remvig L (2012) Knee function in 10-year-old children and adults with Generalised Joint Hypermobility. Knee 19(6):773–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knee.2012.02.002

Juul-Kristensen B, Kristensen JH, Frausing B, Jensen DV, Røgind H, Remvig L (2009) Motor competence and physical activity in 8-year-old school children with generalized joint hypermobility. Pediatrics 124(5):1380–1387. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0294

Kajbafzadeh AM, Sharifi-Rad L, Ladi Seyedian SS, Mozafarpour S, Paydary K (2014) Generalized joint hypermobility and voiding dysfunction in children: is there any relationship? Eur J Pediatr 173(2):197–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-013-2120-6

Karademir G, Atalar AC (2022) Pure elbow dislocation in a child wrestler with underlying hyperlaxity: what is the optimal time to return to competition? Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg/Ulusal Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Dergisi 28(4):545–548. https://doi.org/10.14744/tjtes.2020.95623

Kendel NE, Haamid FW, Christian-Rancy M, O’Brien SH (2019) Characterizing adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding and generalized joint hypermobility. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(6):e27675. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27675

Kendel NE, Stanek JR, Thomas BB, Ardoin SP, O’Brien SH (2022) Assessing bleeding symptoms in pediatric patients with generalized joint hypermobility. Arthritis Care Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25074

Kindgren E, Perez AQ, Knez R (2021) Prevalence of ADHD and autism spectrum disorder in children with hypermobility spectrum disorders or hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a retrospective study. Neuropsychiatr Disease Treatment 17:379–388. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S290494

Kubasadgoudar R, Sanjay P (2012) To assess the prevalence of generalised hypermobility in school children of Dharwad (Urban), Karnataka. Indian J Physiother Occup Therapy 6(4)

Leonardis J, Qashqai A, Wilwert O, Schnorenberg A, Muriello M, Basel D, Slavens B (2021) Three-dimensional motion of the shoulder complex during activities of daily living in youths with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabilitat 102(10):e109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2021.07.509

McDermott P, Wolfe E, Lowry C, Robinson K, French HP (2018) Evaluating the immediate effects of wearing foot orthotics in children with Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (JHS) by analysis of temperospatial parameters of gait and dynamic balance: a preliminary study. Gait Posture 60:61–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.11.005

Moore N, Rand S, Simmonds J (2019) Hypermobility, developmental coordination disorder and physical activity in an Irish paediatric population. Musculoskeletal Care 17(2):261–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1392

Morris SL, O’Sullivan PB, Murray KJ, Bear N, Hands B, Smith AJ (2017) Hypermobility and musculoskeletal pain in adolescents. J Pediatr 181:213–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.060

Mosulishvili T, Loria M (2013) The effectiveness of ridetherapy in children with benign joint hypermobility syndrome during articulatory changes in the knee joint. Georgian Med News 215:76–79

Mu W, Muriello M, Clemens JL, Wang Y, Smith CH, Tran PT et al (2019) Factors affecting quality of life in children and adolescents with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome/hypermobility spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet Part A 179(4):561–569. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.61055

Nash MN, Liu CA, Maestas B, Layugan KU, Culver CC, King J, Kurahara D (2017) Chest pain from hypermobility responding to physical therapy in an adolescent. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 96(12):e219–e222. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000734

Nicholson LL, Adams RD, Tofts L, Pacey V (2017) Physical and psychosocial characteristics of current child dancers and nondancers with systemic joint hypermobility: a descriptive analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy 47(10):782–791. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7331

Nikolajsen H, Juul-Kristensen B, Hendriksen PF, Jensen BR (2021) No difference in knee muscle activation and kinematics during treadmill walking between adolescent girls with and without asymptomatic Generalised Joint Hypermobility. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04018-w

Nikolajsen H, Larsen PK, Simonsen EB, Alkjær T, Falkerslev S, Kristensen JH et al (2013) Gait pattern in 9–11-year-old children with generalized joint hypermobility compared with controls; a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disorders 14(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-341

Nilsson C, Wykman A, Leanderson J (1993) Spinal sagittal mobility and joint laxity in young ballet dancers. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 3(1):206–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01560208

Öhman A, Westblom C, Henriksson M (2014) Hypermobility among school children aged five to eight years: the Hospital del Mar criteria gives higher prevalence for hypermobility than the Beighton score. Clin Exp Rheumatol 32:285–290

Önerge K, Leblebici G, Akalan E, Apti A, Kuchimov SN, Kurt RA (2018) How does hypermobility affect lower extremity function for children with increased femoral anteversion? Describing effects of reduced forefoot sensation on foot pressure distribution: plot study

Ortiz-Rivera CJ, Velasco-Benitez CA, Minota Idarraga AK, Lubo-Cardona NA, VelascoSuarez DA (2022) Joint hypermobility and functional gastrointestinal disorders in a pediatric gastroenterologist outpatient practice. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 74:467–467. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0000000000003446

Pacey V, Adams RD, Tofts L, Munns CF, Nicholson LL (2014) Proprioceptive acuity into knee hypermobile range in children with joint hypermobility syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol 12(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-40

Pacey V, Tofts L, Adams RD, Munns CF, Nicholson LL (2013) Exercise in children with joint hypermobility syndrome and knee pain: a randomised controlled trial comparing exercise into hypermobile versus neutral knee extension. Pediatr Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-11-30

Pacey V, Adams RD, Tofts L, Munns CF, Nicholson LL (2015) Joint hypermobility syndrome subclassification in paediatrics: a factor analytic approach. Arch Dis Child 100(1):8–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-305304

Pacey VT, Adams RD, Munns CF, Nicholson LL (2015) Quality of life prediction in children with joint hypermobility syndrome. J Paediatr Child Health 51(7):869–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12826

Parvaneh VJ, Modaress S, Zahed G, Rahmani K, Shiari R (2020) Prevalence of generalized joint hypermobility in children with anxiety disorders. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03377-0

Pitetti K, Miller RA, Beets MW (2015) Measuring joint hypermobility using the Beighton Scale in children with intellectual disability. Pediatr Phys Ther 27(2):143–150. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0000000000000136

Rejeb A, Fourchet F, Materne O, Johnson A, Horobeanu C, Farooq A, Witvrouw E, Whiteley R (2019) Beighton scoring of joint laxity and injury incidence in Middle Eastern male youth athletes: a cohort study. BMJ Open Sport Exercise Med. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000482

Remvig L, Kümmel C, Kristensen JH, Boas G, Juul-Kristensen B (2011) Prevalence of generalized joint hypermobility, arthralgia and motor competence in 10-year-old school children. Int Musculoskelet Med 33(4):137–145. https://doi.org/10.1179/1753615411Y.0000000009

Revivo G, Amstutz DK, Gagnon CM, McCormick ZL (2019) Interdisciplinary pain management improves pain and function in pediatric patients with chronic pain associated with joint hypermobility syndrome. PM&R 11(2):150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2018.06.018

Şahin NÜ, Şahin N, Kılıç M (2023) Effect of comorbid benign joint hypermobility and juvenile fibromyalgia syndromes on pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders. Postgrad Med. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2023.2176637

Salem T, Hafez H, Ali M (2010) Nonpharmacological treatment using transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for children with benign joint hypermobility syndrome and overactive bladder. UroToday Int J. https://doi.org/10.3834/uij.1944-5784.2010.12.10

Sanjay P, Bagalkoti PS, Kubasadgoudar R (2013) Study of correlation between hypermobility and body mass index in children aged 6–12 years. Indian J Physiother Occup Therapy 7(1):247

Santos MCN, Azevêdo ES (1981) Generalized joint hypermobility and black admixture in school children of Bahia, Brazil. Am J Phys Anthropol 55(1):43–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330550107

Scheper MC, Nicholson LL, Adams RD, Tofts L, Pacey V (2017) The natural history of children with joint hypermobility syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos hypermobility type: a longitudinal cohort study. Rheumatology 56(12):2073–2083. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex148

Schmidt H, Pedersen TL, Junge T, Engelbert R, Juul-Kristensen B (2017) Hypermobility in adolescent athletes: pain, functional ability, quality of life, and musculoskeletal injuries. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy 47(10):792–800. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2017.7682

Schubert-Hjalmarsson E, Öhman A, Kyllerman M, Beckung E (2012) Pain, balance, activity, and participation in children with hypermobility syndrome. Pediatr Phys Therapy 24(4):339–344. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEP.0b013e318268e0ef

Seçkin Ü, Tur BS, Yılmaz Ö, Yağcı İ, Bodur H, Arasıl T (2005) The prevalence of joint hypermobility among high school students. Rheumatol Int 25(4):260–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-003-0434-9

Shulman RJ, Self MM, Czyzewski DI, Goldberg J, Heitkemper M (2020) The prevalence of hypermobility in children with irritable bowel syndrome and functional abdominal pain is similar to that in healthy children. J Pediatr 222:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.033

Sirajudeen MS, Waly M, Alqahtani M, Alzhrani M, Aldhafiri F, Muthusamy H, Unnikrishnan R, Saibannavar R, Alrubaia W, Nambi G (2020) Generalized joint hypermobility among school-aged children in Majmaah region, Saudi Arabia. PeerJ. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9682

Smits-Engelsman B, Klerks M, Kirby A (2011) Beighton score: a valid measure for generalized hypermobility in children. J Pediatr 158(1):119–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.021

Sohrbeck-Nøhr O, Kristensen JH, Boyle E, Remvig L, Juul-Kristensen B (2014) Generalized joint hypermobility in childhood is a possible risk for the development of joint pain in adolescence: a cohort study. BMC Pediatr 14(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-014-0302-7

Subramanyam V, Janaki KV (1996) Joint hypermobility in south Indian children. Indian Pediatr 33:771–771

Tobias JH, Deere K, Palmer S, Clark EM, Clinch J (2013) Joint hypermobility is a risk factor for musculoskeletal pain during adolescence: findings of a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 65(4):1107–1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.37836

Tokhmafshan F, El Andalousi J, Murugapoopathy V, Fillion ML, Campillo S, Capolicchio JP, Jednak R, El Sherbiny M, Turpin S, Schalkwijk J, Matsumoto KI, Brophy PD, Gbadegesin RA, Gupta IR (2020) Children with vesicoureteric reflux have joint hypermobility and occasional tenascin XB sequence variants. Can Urol Assoc J 14(4):E128–E136. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.6068

Tran ST, Jagpal A, Koven ML, Turek CE, Golden JS, Tinkle BT (2020) Symptom complaints and impact on functioning in youth with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Child Health Care 24(3):444–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493519867174

Velasco-Benitez CA, Axelrod C, Valdes LF, Saps M (2020) Functional gastrointestinal disorders, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and joint hypermobility in children: are they related? J Pediatr 218:114–120

Velasco-Benitez CA, Falcon AC, Axelrod C, Fernandez Valdes L, Saps M (2022) Prevalence of joint hypermobility, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and orthostatic hypotension in school-children. Andes Pediatrica Revista Chilena de Pediatria 93(1):53–58. https://doi.org/10.32641/andespediatr.v93i1.3755

Woolston SL, Beukelman T, Sherry DD (2012) Back mobility and interincisor distance ranges in racially diverse North American healthy children and relationship to generalized hypermobility. Pediatr Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-10-17

Wright KE, Furzer BJ, Licari MK, Dimmock JA, Jackson B, Thornton AL (2020) Exploring associations between neuromuscular performance, hypermobility, and children’s motor competence. J Sci Med Sport 23(11):1080–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.06.00

Yazgan P, Geyikli İ, Zeyrek D, Baktiroglu L, Kurcer MA (2008) Is joint hypermobility important in prepubertal children? Rheumatol Int 28(5):445–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-008-0528-5

Butt HI, Tarar SH, Choudhry MA, Asif A, Mehmood S (2014) A study of joint hypermobility in school children of Rawalpindi/Islamabad, Pakistan: prevalence and symptomatic features. Pak J Med Health Sci 8(2):372–375

Al-Shenqiti AM, Emara HA, Algarni FS, Khaled OA, Altaiyar AA, El-Gohary TM (2022) Prevalence of hypermobility in primary school children: a Saudi experience. J Men’s Health. https://doi.org/10.31083/j.jomh1804091

Frydendal T, Eshøj H, Liaghat B, Edouard P, Søgaard K, Juul-Kristensen B (2018) Sensorimotor control and neuromuscular activity of the shoulder in adolescent competitive swimmers with generalized joint hypermobility. Gait Posture 63:221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.05.001

Afari N, Ahumada SM, Wright LJ, Mostoufi S, Golnari G, Reis V, Cuneo JG (2014) Psychological trauma and functional somatic syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 76(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000010

Castori M, Morlino S, Dordoni C, Celletti C, Camerota F, Ritelli M et al (2012) Gynecologic and obstetric implications of the joint hypermobility syndrome (aka Ehlers-Danlos syndrome hypermobility type) in 82 Italian patients. Am J Med Genet Part A 158(9):2176–2182. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.35506

Manning J, Korda A, Benness C, Solomon M (2003) The association oobstructive defecation, lower urinary tract dysfunction and the benign joint hypermobility syndrome: a case–control study. Int Urogynecol J 14(2):128–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-002-1025-0

Bulbena A, Pailhez G, Bulbena-Cabré A, Mallorquí-Bagué N, Baeza-Velasco C (2015) Joint hypermobility, anxiety and psychosomatics: two and a half decades of progress toward a new phenotype. Clin Challenges Biopsychosocial Interface 34:143–157. https://doi.org/10.1159/000369113

Sanches SHB, Osório FDL, Udina M, Martín-Santos R, Crippa JAS (2012) Anxiety and joint hypermobility association: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry 34:53–60. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462012000500005

Bulbena-Cabré A, Baeza-Velasco C, Rosado-Figuerola S, Bulbena A (2019) Updates on the psychological and psychiatric aspects of the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and hypermobility spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 187:482–490. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31955

Ross J, Grahame R (2011) Joint hypermobility syndrome. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c7167

Baeza-Velasco C, Sinibaldi L, Castori M (2018) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, joint hypermobility-related disorders and pain: expanding body-mind connections to the developmental age. ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders 10(3):163–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0252-2

Smith TO, Bacon H, Jerman E, Easton V, Armon K, Poland F, Macgregor AJ (2014) Physiotherapy and occupational therapy interventions for people with benign joint hypermobility syndrome: a systematic review of clinical trials. Disabil Rehabil 36(10):797–803. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.819388

Scheper MC, de Vries JE, Juul-Kristensen B, Nollet F (2014) The functional consequences of generalized joint hypermobility: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-15-243

Wade DT, Halligan PW (2017) The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabil 31(8):995–1004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517709890

Acknowledgements

The University of Edinburgh’s Library and especially Ishbel Leggat contributed to the collection of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LB, JW, WT, and JS: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work. LB, JW, WT, and JS: drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. LB, JW, WT, and JS: final approval of the version to be published. LB, JW, WT, and JS: agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Liron Blajwajs, Joanne Williams, Wendy Timmons and John Sproule declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blajwajs, L., Williams, J., Timmons, W. et al. Hypermobility prevalence, measurements, and outcomes in childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 43, 1423–1444 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05338-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05338-x