Abstract

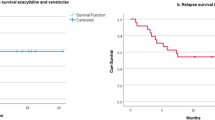

Relapse is a major cause of treatment failure after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT) in myeloid malignancies. Additional strategies have been devised to further maximize the immunologic effect of allo-HCT, notably through maintenance therapy with hypomethylating agents such as 5-azacytidine (AZA). We conducted a single-center retrospective study to investigate the efficacy of AZA after allo-HCT for high-risk myeloid malignancies. All patients transplanted between Jan 2014 and Sept 2019 for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (n = 123), myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 51), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n = 11) were included. Patients who died, relapsed, or developed grade ≥ 2 acute graft-versus-host disease before day + 60 were excluded, as well as those who were eligible for anti-FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 maintenance. Of the 185 included patients, 65 received AZA while 120 did not. Median age at transplant was 59 years; 51.9% of patients were males. The median follow-up was 24 months for both groups. Regarding main patient characteristics and transplantation modalities, the two groups were comparable. In multivariate analyses, there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of 2-year cumulative incidence of relapse (HR = 1.19; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.67–2.12; p = 0.55), overall survival (HR = 0.62; 95%CI 0.35–1.12; p = 0.12) and event-free survival (HR = 0.97; 95%CI 0.60–1.58; p = 0.91) rates. In conclusion, single-agent AZA does not appear to be an optimal drug for preventing post-transplant relapse in patients with high-risk myeloid malignancies. This study highlights the need for prospective studies of alternative therapies or combination approaches in the post-transplant setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Horowitz M, Schreiber H, Elder A et al (2018) Epidemiology and biology of relapse after stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 53:1379–1389. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0171-z

Schmid C, Labopin M, Nagler A et al (2012) Treatment, risk factors, and outcome of adults with relapsed AML after reduced intensity conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood 119:1599–1606. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-08-375840

Caulier A, Drumez E, Gauthier J et al (2019) Scoring system based on post-transplant complications in patients after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for myelodysplastic syndrome: a study from the SFGM-TC. Curr Res Transl Med 67:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retram.2018.08.003

Oran B, Giralt S, Couriel D et al (2007) Treatment of AML and MDS relapsing after reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia 21:2540–2544. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404828

Bazarbachi A, Schmid C, Labopin M et al (2020) Evaluation of trends and prognosis over time in patients with AML relapsing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant reveals improved survival for young patients in recent years. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 26:6475–6482. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-3134

Yafour N, Beckerich F, Bulabois CE et al (2017) Stratégies préventives et thérapeutiques de la rechute après allogreffe de cellules souches hématopoïétiques : recommandations de la Société francophone de greffe de moelle et de thérapie cellulaire (SFGM-TC). Bull Cancer (Paris) 104:S84–S98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bulcan.2017.05.009

Craddock C, Versluis J, Labopin M et al (2018) Distinct factors determine the kinetics of disease relapse in adults transplanted for acute myeloid leukaemia. J Intern Med 283:371–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12720

Yafour N, Beckerich F, Bulabois CE et al (2017) How to prevent relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Curr Res Transl Med 65:65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retram.2017.06.001

Chen Y-B, McCarthy PL, Hahn T et al (2019) Methods to prevent and treat relapse after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, immunomodulating drugs, deacetylase inhibitors, and hypomethylating agents. Bone Marrow Transplant 54:497–507. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0269-3

Lee CJ, Savani BN, Mohty M et al (2019) Post-remission strategies for the prevention of relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia: expert review from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 54:519–530. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-018-0286-2

Choi J, Ritchey J, Prior JL et al (2010) In vivo administration of hypomethylating agents mitigate graft-versus-host disease without sacrificing graft-versus-leukemia. Blood 116:129–139. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-12-257253

Goodyear OC, Dennis M, Jilani NY et al (2012) Azacitidine augments expansion of regulatory T cells after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood 119:3361–3369. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-09-377044

Ehx G, Fransolet G, de Leval L et al (2017) Azacytidine prevents experimental xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease without abrogating graft-versus-leukemia effects. OncoImmunology 6:e1314425. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2017.1314425

Issa J-PJ, Kantarjian HM, Kirkpatrick P (2005) Azacitidine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:275–276. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd1698

Jones PA, Issa J-PJ, Baylin S (2016) Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nat Rev Genet 17:630–641. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.93

Silverman LR, Demakos EP, Peterson BL et al (2002) Randomized controlled trial of azacitidine in patients with the myelodysplastic syndrome: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol 20:2429–2440. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.04.117

Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E et al (2009) Efficacy of azacitidine compared with that of conventional care regimens in the treatment of higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a randomised, open-label, phase III study. Lancet Oncol 10:223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70003-8

Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellström-Lindberg E et al (2010) Azacitidine prolongs overall survival compared with conventional care regimens in elderly patients with low bone marrow blast count acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 28:562–569. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8329

Dombret H, Seymour JF, Butrym A et al (2015) International phase 3 study of azacitidine vs conventional care regimens in older patients with newly diagnosed AML with >30% blasts. Blood 126:291–299. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-01-621664

Hambach L, Ling K-W, Pool J et al (2009) Hypomethylating drugs convert HA-1–negative solid tumors into targets for stem cell–based immunotherapy. Blood 113:2715–2722. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2008-05-158956

Goodyear O, Agathanggelou A, Novitzky-Basso I et al (2010) Induction of a CD8+ T-cell response to the MAGE cancer testis antigen by combined treatment with azacitidine and sodium valproate in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Blood 116:1908–1918. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2009-11-249474

Almstedt M, Blagitko-Dorfs N, Duque-Afonso J et al (2010) The DNA demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine induces expression of NY-ESO-1 and other cancer/testis antigens in myeloid leukemia cells. Leuk Res 34:899–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leukres.2010.02.004

Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A et al (2015) Inhibiting DNA methylation causes an interferon response in cancer via dsRNA including endogenous retroviruses. Cell 162:974–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011

Roulois D, Loo Yau H, Singhania R et al (2015) DNA-demethylating agents target colorectal cancer cells by inducing viral mimicry by endogenous transcripts. Cell 162:961–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.056

Sigalotti L, Altomonte M, Colizzi F et al (2003) 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) treatment of hematopoietic malignancies: a multimechanism therapeutic approach? Blood 101:4644–4646. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-11-3458

de Lima M, Giralt S, Thall PF et al (2010) Maintenance therapy with low-dose azacitidine after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for recurrent acute myelogenous leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome: a dose and schedule finding study. Cancer 116:5420–5431. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25500

Oshikawa G, Kakihana K, Saito M et al (2015) Post-transplant maintenance therapy with azacitidine and gemtuzumab ozogamicin for high-risk acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 169:756–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.13248

Craddock C, Jilani N, Siddique S et al (2016) Tolerability and clinical activity of post-transplantation azacitidine in patients allografted for acute myeloid leukemia treated on the RICAZA Trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 22:385–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.09.004

El-Cheikh J, Massoud R, Fares E et al (2017) Low-dose 5-azacytidine as preventive therapy for relapse of AML and MDS following allogeneic HCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 52:918–921. https://doi.org/10.1038/bmt.2017.31

de Lima M, Oran B, Champlin RE et al (2018) CC-486 Maintenance after stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 24:2017–2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.06.016

Guillaume T, Malard F, Magro L et al (2019) Prospective phase II study of prophylactic low-dose azacitidine and donor lymphocyte infusions following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant 54:1815–1826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-019-0536-y

Maples KT, Sabo RT, McCarty JM et al (2018) Maintenance azacitidine after myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for myeloid malignancies. Leuk Lymphoma 59:2836–2841. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2018.1443334

Oran B, de Lima M, Garcia-Manero G et al (2020) A phase 3 randomized study of 5-azacitidine maintenance vs observation after transplant in high-risk AML and MDS patients. Blood Adv 4:5580–5588. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002544

Schroeder T, Rautenberg C, Haas R et al (2019) Do hypomethylating agents prevent relapse after Allo-HCT? Adv Cell Gene Ther 2:e30. https://doi.org/10.1002/acg2.30

Burchert A, Bug G, Finke J et al (2018) Sorafenib As maintenance therapy post allogeneic stem cell transplantation for FLT3-ITD positive AML: results from the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre sormain trial. Blood 132:661–661. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-112614

Bazarbachi A, Bug G, Baron F et al (2020) Clinical practice recommendation on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia patients with FLT3-internal tandem duplication: a position statement from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica 105:1507–1516. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2019.243410

Spyridonidis A, Labopin M, Savani BN et al (2020) Redefining and measuring transplant conditioning intensity in current era: a study in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-020-0803-y

Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV et al (1978) The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics 34:541. https://doi.org/10.2307/2530374

Fine JP, Gray RJ (1999) A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 94:496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144

Schoenfeld D (1982) Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika 69:239–241. https://doi.org/10.2307/2335876

Gao L, Zhang Y, Wang S et al (2020) Effect of rhG-CSF combined with decitabine prophylaxis on relapse of patients with high-risk MRD-negative AML after HSCT: An Open-Label, Multicenter, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 38:4249–4259. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.03277

Platzbecker U, Middeke JM, Sockel K et al (2018) Measurable residual disease-guided treatment with azacitidine to prevent haematological relapse in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukaemia (RELAZA2): an open-label, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 19:1668–1679. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30580-1

Platzbecker U, Wermke M, Radke J et al (2012) Azacitidine for treatment of imminent relapse in MDS or AML patients after allogeneic HSCT: results of the RELAZA trial. Leukemia 26:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.234

Vij R, Le-Rademacher J, Laumann K et al (2019) A phase II multicenter study of the addition of azacitidine to reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic transplant for high-risk myelodysplasia (and older patients with acute myeloid leukemia): results of CALGB 100801 (Alliance). Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 25:1984–1992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2019.06.007

Ali N, Tomlinson B, Metheny L et al (2020) Conditioning regimen intensity and low-dose azacitidine maintenance after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 61(12):2839–2849. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2020.1789630

Wei AH, Döhner H, Pocock C et al (2019) The QUAZAR AML-001 maintenance trial: results of a phase III international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of CC-486 (oral formulation of azacitidine) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in first remission. Blood 134:LBA-3. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-132405

Yang H, Bueso-Ramos C, DiNardo C et al (2014) Expression of PD-L1, PD-L2, PD-1 and CTLA4 in myelodysplastic syndromes is enhanced by treatment with hypomethylating agents. Leukemia 28:1280–1288. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2013.355

Ørskov AD, Treppendahl MB, Skovbo A et al (2015) Hypomethylation and up-regulation of PD-1 in T cells by azacytidine in MDS/AML patients: A rationale for combined targeting of PD-1 and DNA methylation. Oncotarget 6(11):9612–26. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.3324

Chen C, Liang C, Wang S et al (2020) Expression patterns of immune checkpoints in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol 13:28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-00853-x

Giannopoulos K (2019) Targeting immune signaling checkpoints in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Med 8:236. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8020236

Ravandi F, Daver N, Garcia-Manero G et al (2017) Phase 2 study of combination of cytarabine, idarubicin, and nivolumab for initial therapy of patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 130:815–815. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.815.815

Daver N, Garcia-Manero G, Basu S et al (2019) Efficacy, safety, and biomarkers of response to azacitidine and nivolumab in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a nonrandomized, open-label, phase II study. Cancer Discov 9:370–383. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0774

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Micheline Karam, the study coordinator, for collecting and checking data on-site. The authors wish to acknowledge all staff for their dedication and involvement in the daily care of the patients. The authors thank Rachel Tipton and Ryan Mikati for proofreading the manuscript. Ibrahim Yakoub-Agha would like to thank the “association Capucine” for their support in his research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KJW, IYA, and DB designed the study. BQ and IYA supervised the study. VC, LM, MS, and PC collected clinical data. ED and AD performed data analysis. KJW and DB analyzed data and wrote the initial manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This study was led according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wattebled, KJ., Drumez, E., Coiteux, V. et al. Single-agent 5-azacytidine as post-transplant maintenance in high-risk myeloid malignancies undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 101, 1321–1331 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-022-04821-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-022-04821-y