Abstract

Animals can adapt to changes in their environment through behavioural or developmental plasticity, but studies of these responses tend to focus on either short-term exposure of adults to the changed conditions, or long-term exposure of juveniles. Juvenile guppies Poecilia reticulata reared in low-light environments have previously been shown to make a sensory switch to using olfactory, rather than visual, cues in foraging. It is not clear whether this compensatory sensory plasticity is limited to juveniles, or whether longer term exposure allows adults to similarly adapt. We investigated how adult guppies that were exposed to light or dark environments for 2 and 4 weeks responded to visual, olfactory and a combination of both food cues, in both dark- and light-test environments. We found that after 2 weeks of exposure, adult guppies were better able to locate a food cue in light test environments regardless of their exposure environment. After 4 weeks, however, guppies were more successful at locating the food cue in the environment they had been exposed to, suggesting that dark-exposed guppies adapted their behaviour in response to their environment. We found that foraging was most successful when both visual and olfactory cues were available and least successful in the presence of olfactory cues, suggesting that the mechanism behind the change in success for dark-exposed guppies was not due to increased reliance on, or sensory switch to olfactory cues.

Significance statement

Human-induced environmental change often acts to disrupt an animal’s sensory environment. For example, turbidity can degrade the visual environment, resulting in reduced foraging rates in fish. Juvenile guppies (Poecilia reticulata) can compensate for the reduced visual information available in low-light environments through developmental changes that allow them to rely on an alternative sense, olfaction. This ability, however, may be limited to a critical developmental window, or possible throughout life. Here, we show that while adult guppies are generally better able to locate food resources in well-lit environments, after four (but not two) weeks living under low-light conditions, fish were better able to find food in dark environments than in the light. However, unlike juvenile fish, they did not seem to be relying more on olfactory cues to do so.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Animals are often able to respond to sudden, short-term changes in their environment by altering behaviour, an extremely plastic trait. Behavioural plasticity (also known as contextual or activational plasticity; Stamps and Groothuis 2010; Snell-Rood 2013; Stamps 2016) allows animals to minimise negative consequences of a stressful environment and is usually the first response to altered environmental conditions (Tuomainen and Candolin 2011; Candolin and Wong 2012). Anthropogenic environmental change frequently disrupts an organism’s sensory environment; increased noise created by roads can affect auditory communication in birds (Slabbekoorn and Peet 2003) and eutrophication or turbidity in lakes degrades the visual environment, reducing foraging rates and impacting on a range of other behaviours in fishes (e.g. Heubel and Schlupp 2006; Meager et al. 2006; Candolin et al. 2007; Sundin et al. 2010; Fischer and Frommen 2012; Borner et al. 2015).

Adult fish can adjust their behaviour in response to rapid changes in the visual environment: in turbid water, male threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) increase the frequency of mating displays and display more intense red colouration (Candolin et al. 2007; Engström-Öst and Candolin 2007), while juvenile cod (Gadus morhua) increase searching activity for food sources (Meagre and Batty 2007). Adult fish may also be able to compensate for reduced visual information by increasing their reliance on an alternative sense. For example, threespine sticklebacks can maintain foraging rates by using olfactory cues after relatively short acclimatisation periods (Webster et al. 2007; Johannesen et al. 2012; but see also Sohel et al. 2017), suggesting that these individuals are able to cope to some extent with short-term losses in vision by altering behaviour. However, behavioural plasticity can be limited, particularly if stressors in the environment increase, become permanent, or the animal is unable to effectively move away from the stressor (Schwartz et al. 2006; Thomas 2011).

Exposure from birth allows for an alternative mechanism by which animals can adapt to degraded environments, through adaptive developmental or compensatory plasticity (Rauschecker 1995; West-Eberhard 2003; Monaghan 2008; Nettle and Bateson 2015; Stamps 2016). This type of plasticity is often costlier and less flexible than behavioural plasticity and can be dependent on a critical developmental window (Bateson 1979; West-Eberhard 2003; Knudsen 2004; Stamps 2016). Compensatory sensory plasticity occurs when experience of a degraded sensory environment leads to an increased capacity of an alternative sense (Rauschecker and Kniepert 1994), and has been well documented in juvenile animals, including cats (Felis catus; Rauschecker 1995), rats (Rattus norvegicus; Ryugo et al. 1975) and humans (Homo sapiens; Röder et al. 1999). Guppies (Poecilia reticulata) reared from birth in a low-light environment, for example, make a sensory switch from vision to olfaction when detecting food cues, enabling them to maintain foraging rates (Chapman et al. 2010b).

Studies of plasticity in responses of fish to changed environments tend to focus either on long-term rearing of juveniles (Chapman et al. 2009, 2010a, b; Ehlman et al. 2015; Sakai et al. 2016; Wright et al. 2018) or short-term exposure of adults (Ward et al. 2008; Johannesen et al. 2012, 2014; Fischer and Frommen 2013; Kimbell and Morrell 2015a, b). Costly behaviourally plastic responses, such as increased activity (juvenile cod (G. morhua); Meager and Batty 2007) may be effective in the short term, but not sustainable over longer times cales, while mechanisms such as learning (Odling-Smee and Braithwaite 2003; Dukas 2013), physiological or morphological changes (Webster et al. 2011) may allow responses to be maintained or improved. However, developmental plasticity may constrain individuals, should the environment to which individuals are adapted change later in life (Padilla and Adolph 1996; Metcalfe and Monaghan 2001; Zimmerman et al. 2001; Monaghan 2008; Fuller et al. 2010; Brust et al. 2014).

Here, we explore whether exposure to an altered environment over a period of several weeks can result in the development of compensatory responses in adult, rather than juvenile, fish. We explore the following hypotheses:

-

a)

Developmental plasticity hypothesis

Firstly, if adult guppies exposed to low-light environments are able to compensate for reduced visual information in low-light conditions through plastic responses, we predict increased foraging success (measured by ability to locate a food cue) in low-light environments relative to guppies that have not previously experienced low-light environments.

-

b)

Sensory compensation hypothesis

Secondly, if sensory compensation can occur at any age, and is not limited to a critical developmental window early in life (Bateson 1979; West-Eberhard 2003; Knudsen 2004; Stamps 2016), we would see this as a switch from reliance on visual to olfactory cues that has previously been seen in juveniles (Chapman et al. 2010b).

-

c)

Developmental constraint hypothesis

Finally, if adult guppies are not able to adapt to low-light environments even after several weeks, this suggests that developmental plasticity constrains their ability to respond (Padilla and Adolph 1996; Metcalfe and Monaghan 2001; Zimmerman et al. 2001; Monaghan 2008; Fuller et al. 2010; Brust et al. 2014).

Methods

Study species and exposure environments

All fish used in this experiment were descendants of wild-caught guppies (P. reticulata) from Trinidad. Stock tanks of guppies were maintained in aquaria (20 × 40 × 40 cm) at the University of Hull at ~ 26 °C on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle and fed daily on ZM fine sinking food by aquarium technical staff (ZM Systems, Hampshire, UK).

Two hundred fifty-two male and female guppies over 10 mm in standard body length were randomly assigned to one of two light intensity exposure environments: relatively high light intensity (~ 300 lx; “light exposure environment”) and relatively low light intensity (~ 1.5 lx; “dark exposure environment”). Ten millimetres is the minimum standard length at which males and females in the laboratory population began to show differentiation in the anal fin that allows the sexes to be distinguished before male colouration emerges. Only fish that could be confidently identified as male or female (and were therefore likely to be sexually mature; generally occurring by 7 weeks for males and between 10 and 20 weeks for females; Magurran 2005) were used. Body length was not recorded at the start of the experiment, but mean ± SD of standard body length at 2 weeks was 16.0 ± 1.5 mm for males and 17.7 ± 3.3 mm for females, and at 4 weeks was 16.1 ± 2.2 mm for males and 18.2 ± 3.8 mm for females. Females were thus significantly larger than males (unequal variance t tests: 2 weeks: t = 4.80, df = 143.95, p < 0.001; 4 weeks: t = 4.56, df = 124.39, p < 0.001).

The dark exposure level and terminology was chosen to match Chapman et al. (2010b), where 1.545 ± 0.11 lx was sufficient to induce compensatory sensory plasticity in juvenile guppies. Exposure tanks measured 20 × 20 × 20 cm, contained an artificial plant and were held in our aquarium facility on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle, such that all fish (light and dark exposure environments) experienced complete darkness for 12 h per day. The light exposure environments were under normal aquarium room lighting, while the dark exposure environments were created by turning off the aquarium lights directly above the tanks (but leaving the room lights on the specified light cycle), and isolating the tanks from the main room using a thin black polycotton sheet. To control for the positioning of the sheet, light tanks were isolated from the room by a thin white sheet. All exposure tanks (light and dark) were kept on the same circulating aquarium system with a 10% daily water change using a 50:50 mixture of purified water and filtered tap water. To minimise algae growth (which may otherwise be used as a food source), UV filters were used on the system, and all tanks were carefully cleaned twice weekly and the aquarium plants changed weekly to prevent algae build up. This caused minimal disturbance to the fish.

Fish were placed into the exposure tanks at an initial density of six fish per tank (three males and three females) and fed twice a day with crushed ZM flake food using a 5 × 2 mm spatula to ensure each tank received an equal quantity of food. Fish were fed flake food during exposure to allow them to become familiar with the food used in the trials (see below). Fish were held in the exposure tanks for a total of 4 weeks. After 2 weeks, fish were removed from the tanks and randomly assigned to a cue treatment (visual cues only, olfactory cues only or both) for the foraging experiment (see below). Each fish was tested individually in light- and dark-test environments, with 24 h between trials before being returned to the tank. The same fish were then exposed for a further 2 weeks, for a total of 4 weeks. We carried out 21 replicates (21 groups of 6 fish = 126 fish) for each of light and dark exposure environments.

Foraging experiment

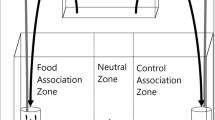

Foraging trials used a similar methodology to that in Chapman et al. (2010b). Trials took place in a rectangular plastic tank (40 × 25 × 15 cm) filled to a depth of 5 cm with water taken from the aquarium system. At one end of the tank, two solid, transparent cylindrical containers (diameter 7.5 cm, height 10 cm) also filled to a depth of 5 cm were fixed to the base of the tank. They were positioned in the corners of the tank with a minimum distance of 10 cm between them. The cylinders contained visual cues from food during the relevant trials, and contained no food during trials that did not involve visual cues. No olfactory cues were able to pass from the cylinders to the test tank. A 3-cm preference zone was drawn around each container. Two plastic clips were placed on the outside of these containers, which held tubes to allow for olfactory cues to enter the test tank below the water line, during the relevant trials. Twelve centimeter from the opposite end of the tank, a horizontal “start line” was drawn, dividing the tank into two sections (a starting section and a choice section).

The experimental tank was housed within a wooden shelter (70 × 50 × 65 cm) with an open front and an opening directly above the tank where a Panasonic SDR S26 video camera was placed, so fish could be observed without disturbance. The video camera was connected to a laptop, and data recording took place in real time. An aquarium light attached to a clamp stand was placed inside the shelter to ensure the light trial environments received a similar light intensity as the light exposure environment. In the dark trials, this was switched off and the “colour night view” mode on the video camera was used, which allowed the fish to be observed. The shelter was then covered with a black (dark trials) or white (light trials) polycotton sheet to both ensure the correct light intensity and minimise disturbance to the fish during the trials.

Visual cues were created by placing 0.2 g of crushed flake food (ZM fish food; following Chapman et al. 2010b) onto the surface of the water of one of the containers, using a funnel from outside the wooden shelter to minimise disturbance. Olfactory cues were created by mixing 10 g of flake food in 1 l of purified water and filtering this through a fine mesh to remove any visual cues. A control cue was made up of 1 l of purified water with 0.2 ml of yellow food dye (to match the colour of the food cues). These cues were dispensed via a peristaltic pump that released the cues through tubes connected to the cylindrical containers at a rate of 6 ml per minute. An overflow pipe was placed 5 cm above the base of the tank at the end of the tank opposite the cue cylinders to maintain a constant water level. For the visual-only and olfactory-only treatments, only the relevant cue was added. For the both cues treatment, both visual and olfactory cues were added at the same side. The side containing the cues was randomised.

Experimental protocol

Twenty-four hours prior to experiments, all fish within an exposure tank were placed into two holding tanks (40 × 20 × 20 cm), both separated into three equal-sized compartments (each 13 × 20 × 20 cm) and fed. Compartments were separated with clear perforated barriers, which allowed visual and olfactory communication between the test fish, to reduce possible stress caused by separation from conspecifics. Each of the six fish were randomly assigned to a cue treatment (two visual, two olfactory and two both, but such that one male and one female was assigned to each), and tested in both light- and dark-test environments, separated by 24 h. An hour before each trial, the fish were acclimatised to the trial-lighting conditions by placing them in a separate small tank (20 × 20 × 20 cm). At the start of each trial, an individual was placed in the test tank and given 2 min to explore the tank. After the acclimatisation period, and once the fish had returned to the start section, the food cues were added. The trial began when the fish subsequently crossed the start line. Each trial lasted 5 min.

Using the video camera to directly observe the fish, we recorded (using two stopwatches) the time in seconds spent in the preference zones of both the cue and control cylinders, from which we calculated the proportion of this time spent with the cue (Chapman et al. 2010b). At the end of the 5-min trial, fish were returned to their holding tank compartment, allowing us to track individual fish between the two trials in different test environments. When the trials for each set of fish were completed, the fish were fed. They remained in the holding tanks for a further 24 h to allow them to be retested under the alternative lighting environment. After the second trial, fish were measured to the nearest mm, released into their home tank and fed. Fish were tested after 2 weeks in their exposure tanks and again at 4 weeks. Individuals were not marked or tagged, so we were unable to track individuals between the 2-week and 4-week trials. The order the fish experienced light- and dark-test environments was alternated. The tank was emptied and rinsed with conditioned water from the aquarium system between each experiment to remove any olfactory cues from food or the previous fish. We carried out a total of 432 trials on 216 individual fish at 2 weeks, and 392 trials on 196 fish at 4 weeks. Due to logistical constraints and the complexity of the experiment, observers were not blind to the rearing environment or rearing duration experienced by the test fish, and could not be blind to test environment or the presence/absence of visual cues. Fish that failed to enter both control and cue zones or did not cross over the start line were removed from the analysis (2 weeks: n = 73/432 trials and 4 weeks: 61/392 trials). Twenty fish died between the 2- and 4-week testing (light exposed, 5; dark exposed, 15). Figure 1 shows schematically how fish moved through the experiment, and gives final sample sizes for each combination of rearing environment, cue availability, test environment and exposure duration.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using R version 3.3.2 (R Core Team 2016).

Firstly, to confirm that the fish could distinguish the cue cylinders from the control cylinders, we carried out one-sample t tests to assess whether the proportion of the time spent with the cue differed from 0.5 (random expectation). Proportion data were arcsin transformed prior to analysis to meet the assumptions of normality of residuals. To assess the both and visual only cue treatments, we used only data from fish exposed for 2 weeks to light environments, and tested in the light. For the olfactory cues, we used fish that had spent 4 weeks in the dark exposure environment, as these would be predicted to be the most likely to rely on olfactory cues in foraging.

We used linear mixed effects models to assess the effect of rearing environment (light or dark), test environment (light or dark), cue treatment (both, visual only, olfactory only) and exposure duration (2 or 4 weeks) on the proportion of time spent with the cue. We included sex and size as main effects to control for any effects of these characteristics on foraging behaviour. The assumptions of the model were checked via visual inspection of plots of residuals and quantile-quantile plots, and consequently, proportion data were arcsin transformed prior to analysis. Rearing tank was added as random effects to account for the possible non-independence of individuals from the same exposure tank, but because individuals could not be reliably tracked between 2 and 4 weeks, individual identity could not be included as an additional random effect. Thus, our model was more conservative than if individuals could have been tracked, as between-individual variability could not be accounted for. Following this, we carried out the same analysis for 2- and 4-week exposures separately, this time additionally including individual identity (nested within rearing tank) as a random factor to control for the repeated testing of the same individuals in both light and dark environments separated by 24 h. Nonsignificant two- and three-way interactions were removed from the models following Crawley (2007), and the minimum adequate models containing all main effects and significant interactions are presented here.

Finally, we used proportion tests to compare the proportion of successful trials in dark- and light-test environments, each combination of exposure environment and duration, to explore whether there was an effect of light and test environment on propensity to forage.

Results

Fish exposed to light environments for 2 weeks and tested in light environments could successfully detect the cues in the visual and both cue treatments, spending a greater proportion of time with the cue cylinder than expected by chance (one-sample t tests: both cues: t = 6.327, df = 26, p < 0.001; visual cues: t = 7.839, df = 30, p < 0.001). Fish exposed to dark environments for 4 weeks and tested in the dark spend more time with the olfactory cue cylinder than expected by chance (one-sample t test, t = 3.133, df = 21, p = 0.005), indicating that fish could successfully detect the cues in the conditions in which they would be expected to do so.

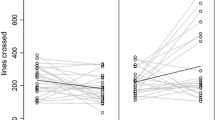

When considering both 2- and 4-week exposure durations together, we found a significant interaction between test environment and exposure duration (Table 1a). Fish tested in light environments located the cue more successfully, but less so after 4 weeks than after two (Fig. 2). In addition, fish foraged more successfully when both visual and olfactory cues were available than when only one of the cues was available. To further explore why fish should spend less time associating with the cue in light environments after 4 weeks, we analysed the two exposure durations separately. After a 2-week exposure duration, we found significant effects of test environment and cue treatment, but not exposure environment, on the proportion of time spent with the food cue (Table 1b). Fish spent a greater proportion of time with the cue in the light environment, and when both visual and olfactory cues were available (Fig. 3a, c, e). There was no effect of exposure environment and no significant interactions. After a 4-week exposure duration, we found a significant two-way interaction between exposure environment and trial-test environment (Table 1c). Fish spent a greater proportion of time with the cue in the test environment they were previously exposed to, irrespective of cue availability. Guppies exposed to light environments spent a greater proportion of time with the food cue in light environment trials and dark-exposed guppies spent a greater proportion of time with the cue under dark trial conditions (Fig. 3b, d, f). There was also a marginally significant effect of sex, with males spending a lower proportion of time with the cue than females.

Proportion of time spent in the cue detection zone after adult fish had been exposed to light and dark exposure environments for 2 or 4 weeks. Shaded bars represent dark-test environments, unshaded bars represent light-test environments, raw data are plotted as open points overlaid on the relevant boxplot showing the median (heavy line), and upper and lower quartiles (box). Whiskers extend to the most extreme data point that is no more than 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR). The horizontal dashed line at 0.5 represents a random choice

Proportion of time spent in the cue detection zone after adult fish had been exposed to light and dark environments for two (left panels) and four (right panels) weeks, with either both visual and olfactory cues (a, b), visual cues only (c, d) or olfactory cues only (e, f). Shaded bars represent dark-test environments, unshaded bars represent light-test environments, raw data are plotted as open points overlaid on the relevant boxplot showing the median (heavy line), and upper and lower quartiles (box). Whiskers extend to the most extreme data point that is no more than 1.5× the interquartile range (IQR). The horizontal dashed line at 0.5 represents a random choice

Fish exposed to light environments for 2 or 4 weeks were significantly more likely to participate in the trial (generate data) in light-test environments than in dark-test environments (2 weeks, 90/106 (84.9%) fish in light-test environments vs. 75/106 (70.7%) in dark-test environments, proportion test, χ2 = 5.358, df = 1, p = 0.021; 4 weeks: 94/101 (91.8%) vs. 76/101 (75.2%), proportion test, χ2 = 10.731, df = 1, p = 0.001). In contrast, fish exposed to dark environments for 2 or 4 weeks were equally likely to generate data in dark- and light-test environments (2 weeks: 101/110 (91.8%) vs. 93/110 (84.5%), proportion test, χ2 = 2.137, df = 1, p = 0.144; 4 weeks: 84/95 (88.4%) vs. 77/95 (81.1%), proportion test, χ2 = 1.467, df = 1, p = 0.226).

Discussion

We found that after 4 weeks exposure to a light or dark environment, guppies foraged more successfully in the environment in which they had previous been exposed, and when both visual and olfactory cues were available. A 2-week exposure was not sufficient for this to occur, and all guppies foraged more successfully in light environments. This suggests that over the period of exposure, guppies developed some adaptation to their exposure environment allowing them to forage more successfully in that test environment. However, both dark- and light-exposed fish showed similar responses to the different cue types.

There was no evidence that this increased success in dark environments for dark-exposed fish was due to compensatory sensory plasticity, where individuals compensate for decreased vision by increasing reliance on olfactory cues, as previously seen in juvenile guppies (Chapman et al. 2010b). Dark-reared fish were most successful foraging when both visual and olfactory cues were available, and their success in locating the cue was lowest in the olfactory-only treatment. The brains of fishes remain plastic throughout life (Ebbesson and Braithwaite 2012), and adult male guppies kept in different social conditions show different changes in brain size (Kotrschal et al. 2012) suggesting that a plastic response in cue use may be possible, but it was not seen here. A longer (more than 4 weeks) exposure duration may be required before plastic changes can occur (Chapman et al. 2010b; Kotrschal et al. 2012), or exposure during a critical developmental period early in life may be required for sensory plasticity in cue use to occur (Rauschecker 1995; West-Eberhard 2003; Knudsen 2004).

Nevertheless, we did observe that after 4 weeks, guppies foraged most successfully in their exposure environment, suggesting that some sort of compensatory behaviour or response did occur after a 4 week (but not 2 week) exposure. This may result from eye acclimation to the dark environment, increased familiarity with foraging in dark environments, or decreased familiarity with light environments.

Dark adaptation of the eyes is a rapid process that is unlikely to explain why adaptation was observed after 4 weeks but not after 2. In teleost fish, as in other vertebrates, the retinal photoreceptors and retinal epithelium in the eye respond to changes in the lighting environment, to adapt the retina for vision in both bright and dim-light vision (Walls 1942; Rodieck 1973). Such adaptation to dark and light environments is a rapid process: human eyes take approximately 20–40 min to fully adapt from bright sunlight to complete darkness (Jackson et al. 1999). Similarly, in zebrafish (Danio rerio), a fully light-adapted state is reached after 1 h of light adaptation (Hodel et al. 2006), and silver eels (Anguilla anguilla), show retinomotor movements associated with light and dark adaptation after 2 h (Es-Sounni and Ali 1986). All fish were exposed to the test environment for 1 h before trials began, and so, normal dark- or light-adaptation processes should have occurred for both dark- and light-exposed fish. Over a longer time period of exposure, however, it is possible that eyes could have developed further sensitivity, although studies of longer term visual deprivation tend to focus on the visual impairment that results from exposure during critical developmental windows (e.g. Kroger et al. 2003; Mitchell et al. 2015).

Experience of necessarily feeding in the dark means dark-exposed fish become accustomed to seeking out food in this environment, while light-exposed guppies, which would not normally be foraging under low-light conditions (Magurran 2005) would not. Additionally, guppies exposed to dark conditions may become unfamiliar with foraging in the light, leading them to behave in a risk-averse manner when tested in light environments. Guppies are known to become bolder in environments they are more familiar with, and spend more time exploring familiar environments (Martin and Réale 2008; Goldenberg et al. 2014), which would allow them to more readily locate a food source. We might, however, expect associations like this to develop more rapidly: guppies can learn to locate a food source within three trials (Lachlan et al. 1998) and remember the identity of conspecifics in 14 days (Griffiths and Magurran 1997). Minnows can learn to recognise pike odour within 2–4 days (Brown et al. 1997) or 14 days (Chivers and Smith 1995), and a single exposure to a chemical cue can lead to marked and long-lasting changes in antipredator behaviour in multiple species (Brown 2003).

A lack of response at 2 weeks is perhaps surprising, as guppies and other fishes can respond rapidly to changing environments in other contexts. Male guppies reared as juveniles in dark conditions, for example, respond flexibly to current lighting environment in mating behaviour regardless of their rearing environment (Chapman et al. 2009). Sticklebacks can modify their behaviour towards an unavailable food source in a matter of minutes (Bell and Peeke 2012), and in some cases able to maintain foraging rates in turbid water without prior exposure, by using olfactory cues (Webster et al. 2007; Johannesen et al. 2012; but see Sohel et al. 2017), although other fish species do not (e.g. striped trumpeter (Latris lineata): Cobcroft et al. 2001, sablefish (Anoplopoma fimbria): De Robertis et al. 2003). If animals are not able to respond flexibly to rapid changes in their environment, this may have detrimental effects on their foraging success. Alternatively, as short-term variability in visibility in aquatic environments is common due to water depth, turbidity or canopy cover, the benefits of changing behaviour may be outweighed by the costs of doing so (DeWitt et al. 1998), and a change in behaviour may not be observed.

Our study highlights the importance of considering the impact of environmental change over different life stages and time scales. Research into the effect of environmental change on individual behaviour is usually carried out as a long-term study rearing juveniles from an early age (Cobcroft et al. 2001; Carere et al. 2005; Chapman et al. 2010a, b; Weintraub et al. 2010; Gray et al. 2012; Zambonino-Infante et al. 2013; Brust et al. 2014), or via the short-term exposure of adults to degraded conditions (Engström-Öst et al. 2006; Ward et al. 2008; Johannesen 2012; Kimbell and Morrell 2015a, b). While short-term experiments offer important insights into the immediate response of animals to a pollution event, for example, longer term studies are needed to understand the impact of more gradual or long-lasting change on both adult and juvenile individuals. A limitation of our study is that we were unable to track individuals between 2 and 4 weeks; future studies could build on this by tracking individuals over time. Understanding how animals respond to changes to their sensory environments is critical to understanding the consequences of environmental change for individuals, populations and communities (Hoverman and Relyea 2007; Wong and Candolin 2015). The ability of aquatic organisms to respond flexibly or plastically to the loss of visual information, or other senses, may differ depending on the life stage of the organism. Our results suggest that extended exposure may allow adult individuals to alter their behaviour, allowing them to compensate somewhat for the detrimental effects of the change, but any negative impact change on growth and survival can occur over relatively short time scales (Berg and Northcote 1985) and raises the question of whether this compensation will be sufficient.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files: ESM_1.xlsx).

References

Bateson P (1979) How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for? Anim Behav 27:470–486

Bell AM, Peeke HVS (2012) Individual variation in habituation: behaviour over time toward different stimuli in threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Behaviour 149:1339–1365

Berg L, Northcote TG (1985) Changes in territorial, gill-flaring, and feeding-behavior in juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) following short-term pulses of suspended sediment. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 42:1410–1417

Borner K, Krause S, Mehner T, Uusi-Heikkilä S, Ramnarine I, Krause J (2015) Turbidity affects social dynamics in Trinidadian guppies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 69:645–651

Brown GE (2003) Learning about danger: chemical alarm cues and local risk assessment in prey fishes. Fish Fish 4:227–234

Brown GE, Chivers DP, Smith RJF (1997) Differential learning rates of chemical versus visual cues of a northern pike by fathead minnows in a natural habitat. Environ Biol Fish 49:89–96

Brust V, Krüger O, Naguib M, Krause ET (2014) Lifelong consequences of early nutritional conditions on learning performance in zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata). Behav Process 103:320–326

Candolin U, Wong BBM (2012) Behavioural responses to a changing world. In: Mechanisms and consequences. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Candolin U, Salesto T, Evers M (2007) Changed environmental conditions weaken sexual selection in sticklebacks. J Evol Biol 20:233–239

Carere C, Drent PJ, Privitera L, Koolhaas JM, Groothuis TGG (2005) Personalities in great tits, Parus major: stability and consistency. Anim Behav 70:795–805

Chapman BB, Morrell LJ, Krause J (2009) Plasticity in male courtship behaviour as a function of light intensity in guppies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 63:1757–1763

Chapman BB, Morrell LJ, Krause J (2010a) Unpredictability in food supply during early life influences boldness in fish. Behav Ecol 21:501–506

Chapman BB, Morrell LJ, Tosh CR, Krause J (2010b) Behavioural consequences of sensory plasticity in guppies. Proc R Soc Lond B 277:1395–1401

Chivers DP, Smith RJF (1995) Free-living fathead minnows rapidly learn to recognize pike as predators. J Fish Biol 46:949–954

Cobcroft JM, Pankhurst PM, Hart PR, Battaglene SC (2001) The effects of light intensity and algae-induced turbidity on feeding behaviour of larval striped trumpeter. J Fish Biol 59:1181–1197

Crawley M (2007) The R book. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester

De Robertis A, Ryer CH, Veloza A, Brodeur RD (2003) Differential effects of turbidity on prey consumption of piscivorous and planktivorous fish. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 60:1517–1526

DeWitt TJ, Sih A, Wilson DS (1998) Costs and limits of phenotypic plasticity. Trends Ecol Evol 13:77–81

Dukas R (2013) Effects of learning on evolution: robustness, innovation and speciation. Anim Behav 85:1023–1030

Ebbesson LOE, Braithwaite VA (2012) Environmental effects on fish neural plasticity and cognition. J Fish Biol 81:2151–2174

Ehlman SM, Sandkam BA, Breden F, Sih A (2015) Developmental plasticity in vision and behavior may help guppies overcome increased turbidity. J Comp Physiol A 201:1125–1135

Engström-Öst J, Candolin U (2007) Human-induced water turbidity alters selection on sexual displays in sticklebacks. Behav Ecol 18:393–398

Es-Sounni A, Ali MA (1986) Ultrastructure of the retinal pigmented epithelium of light- and dark-adapted young, pigmented, and mature silver eels, Anguilla anguilla (Pisces, Teleostei). Zoomorphology 106:179–184

Fischer S, Frommen JG (2013) Eutrophication alters social preferences in three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 67:293–299

Fuller RC, Noa LA, Strellner RS (2010) Teasing apart the many effects of lighting environment on opsin expression and foraging preference in bluefin killifish. Am Nat 176:1–13

Goldenberg SU, Borcherding J, Heynen M (2014) Balancing the response to predation—the effects of shoal size, predation risk and habituation on behaviour of juvenile perch. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 68:989–998

Gray SM, McDonnell LH, Cinquemani FG, Chapman LJ (2012) As clear as mud: turbidity induces behavioral changes in the African cichlid Pseudocrenilabrus multicolor. Curr Zool 58:146–157

Griffiths SW, Magurran AE (1997) Familiarity in schooling fish: how long does it take to acquire? Anim Behav 53:945–949

Heubel KU, Schlupp I (2006) Turbidity affects association behaviour in male Poecilia latipinna. J Fish Biol 68:555–568

Hodel C, Neuhauss SC, Biehlmaier O (2006) Time course and development of light adaptation processes in the outer zebrafish retina. Anat Rec A 288:653–662

Hoverman JT, Relyea RA (2007) How flexible is phenotypic plasticity? Developmental windows for trait induction and reversal. Ecology 88:693–705

Jackson GR, Owsley C, McGwin G Jr (1999) Aging and dark adaptation. Vis Res 39:3975–3982

Johannesen A, Dunn AM, Morrell LJ (2012) Olfactory cue use by three-spined sticklebacks foraging in turbid water: prey detection or prey location? Anim Behav 84:151–158

Johannesen A, Dunn AM, Morrell LJ (2014) Prey aggregation is an effective olfactory predator avoidance strategy. PeerJ 2:e408

Kimbell HS, Morrell LJ (2015a) Turbidity influences individual and group level responses to predation in guppies, Poecilia reticulata. Anim Behav 103:179–185

Kimbell HS, Morrell LJ (2015b) Turbidity weakens selection for assortment in body size in groups. Behav Ecol 27:545–552

Knudsen EI (2004) Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J Cogn Neurosci 16:1412–1425

Kotrschal A, Rogell B, Maklakov AA, Kolm N (2012) Sex-specific plasticity in brain morphology depends on social environment of the guppy, Poecilia reticulata. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66:1485–1492

Kroger HH, Knoblauch B, Wagner H-J (2003) Rearing in different photic and spectral environments changes the optomotor response to chromatic stimuli in the cichlid fish Aequidens pulcher. J Exp Biol 206:1643–1648

Lachlan RF, Crooks L, Laland KN (1998) Who follows whom? Shoaling preferences and social learning of foraging information in guppies. Anim Behav 56:181–190

Magurran AE (2005) Evolutionary ecology of the Trinidadian guppy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Martin JGA, Réale D (2008) Temperament, risk assessment and habituation to novelty in eastern chipmunks, Tamias striatus. Anim Behav 75:309–318

Meager JJ, Batty RS (2007) Effects of turbidity on the spontaneous and prey-searching activity of juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Phil Trans R Soc B 362:2123–2130

Meager JJ, Domenici P, Shingles A, Utne-Palm AC (2006) Escape responses in juvenile Atlantic cod Gadus morhua L.: the effects of turbidity and predator speed. J Exp Biol 209:4174–4184

Metcalfe NB, Monaghan P (2001) Compensation for a bad start: grow now, pay later? Trends Ecol Evol 16:254–260

Mitchell DE, Crowder NA, Holman K, Smithen M, Duffy KR (2015) Ten days of darkness causes temporary blindness during an early critical period in felines. Proc R Soc Lond B 282:20142756

Monaghan P (2008) Early growth conditions, phenotypic development and environmental change. Phil Trans R Soc B 363:1635–1645

Nettle D, Bateson M (2015) Adaptive developmental plasticity: what is it, how can we recognize it and when can it evolve? Proc R Soc Lond B 282:20151005

Odling-Smee L, Braithwaite VA (2003) The role of learning in fish orientation. Fish Fish 4:235–246

Padilla DK, Adolph SC (1996) Plastic inducible morphologies are not always adaptive: the importance of time delays in a stochastic environment. Evol Ecol 10:105–117

R Core Team (2016) R - A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, https://www.R-project.org/

Rauschecker JP (1995) Compensatory plasticity and sensory substitution in the cerebral cortex. Trends Neurosci 18:36–43

Rauschecker JP, Kniepert U (1994) Auditory localization behavior in visually deprived cats. Eur J Neurosci 6:149–160

Röder B, Teder-Sälejärvi W, Sterr A, Rösler F, Hillyard SA, Neville HJ (1999) Improved auditory spatial tuning in blind humans. Nature 400:162–166

Rodieck RW (1973) The vertebrate retina. Principles of structure and function. W.H. Freeman, San Francisco, CA

Ryugo DK, Ryugo R, Globus A, Killackey HP (1975) Increased spine density in auditory-cortex following visual or somatic deafferentation. Brain Res 90:143–146

Sakai Y, Ohtsuki H, Kasagi S, Kawamura S, Kawata M (2016) Effects of light environment during growth on the expression of cone opsin genes and behavioral spectral sensitivities in guppies (Poecilia reticulata). BMC Evol Biol 16:106

Schwartz MW, Iverson LR, Prasad AM, Matthews SN, O'Connor RJ (2006) Predicting extinctions as a result of climate change. Ecology 87:1611–1615

Slabbekoorn H, Peet M (2003) Ecology: birds sing at a higher pitch in urban noise - great tits hit the high notes to ensure that their mating calls are heard above the city's din. Nature 424:267–267

Snell-Rood EC (2013) An overview of the evolutionary causes and consequences of behavioural plasticity. Anim Behav 85:1004–1011

Sohel S, Mattila J, Lindström K (2017) Effects of turbidity on prey choice of three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). Mar Ecol Prog Ser 566:159–167

Stamps JA (2016) Individual differences in behavioural plasticities. Biol Rev 91:534–567

Stamps J, Groothuis TGG (2010) The development of animal personality: relevance, concepts and perspectives. Biol Rev 85:301–325

Sundin J, Berglund A, Rosenqvist G (2010) Turbidity hampers mate choice in a pipefish. Ethology 116:713–721

Thomas CD (2011) Translocation of species, climate change, and the end of trying to recreate past ecological communities. Trends Ecol Evol 26:216–221

Tuomainen U, Candolin U (2011) Behavioural responses to human-induced environmental change. Biol Rev 86:640–657

Walls GL (1942) The vertebrate eye and its adaptive radiation. Cranbrook Press, Bloomfield Hills

Ward AJ, Duff AJ, Horsfall JS, Currie S (2008) Scents and scents-ability: pollution disrupts chemical social recognition and shoaling in fish. Proc R Soc Lond B 275:101–105

Webster MM, Atton N, Ward AJW, Hart PJB (2007) Turbidity and foraging rate in threespine sticklebacks: the importance of visual and chemical prey cues. Behaviour 144:1347–1360

Webster MM, Atton N, Hart PJB, Ward AJW (2011) Habitat-specific morphological variation among threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) within a drainage basin. PLoS One 6:e21060

Weintraub A, Singaravelu J, Bhatnagar S (2010) Enduring and sex-specific effects of adolescent social isolation in rats on adult stress reactivity. Brain Res 1343:83–92

West-Eberhard MJ (2003) Developmental plasticity and evolution. Oxford University Press, New York

Wong BMM, Candolin U (2015) Behavioral responses to changing environments. Behav Ecol 26:665–673

Wright DS, Rietveld, Maan ME (2018) Developmental effects of environmental light on male nuptial coloration in Lake Victoria cichlid fish. PeerJ 6:e4209

Zambonino-Infante JL, Claireaux G, Ernande B, Jolivet A, Quazuguel P, Sévère A, Huelvan C, Mazurais D (2013) Hypoxia tolerance of common sole juveniles depends on dietary regime and temperature at the larval stage: evidence for environmental conditioning. Proc R Soc Lond B 280:20123022

Zimmermann A, Stauffacher M, Langhans W, Würbel H (2001) Enrichment dependent differences in novelty exploration in rats can be explained by habituation. Behav Brain Res 121:11–20

Acknowledgements

We thank Alan Smith, Rose Wilcox, Sonia Jennings and Vic Swetez for aquarium support at the University of Hull, and the anonymous referees for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a University of Hull PhD Scholarship awarded to HSK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. The project was approved prior to commencement by the ethical review committees of the former School of Biological, Biomedical and Environmental Sciences and the Faculty of Science and Engineering at the University of Hull (reference numbers U021 and U094).

Additional information

Communicated by J. Frommen

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(XLSX 66 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimbell, H.S., Chapman, B.B., Dobbinson, K.E. et al. Foraging guppies can compensate for low-light conditions, but not via a sensory switch. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 73, 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2640-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-019-2640-9