Abstract

Purpose

Diagnosis of spondylodiscitis (SD) may be challenging due to the nonspecific clinical and laboratory findings and the need to perform various diagnostic tests including serologic, imaging, and microbiological examinations. Homogeneous management of SD diagnosis through international, multidisciplinary guidance would improve the sensitivity of diagnosis and lead to better patient outcome.

Methods

An expert specialist team, comprising nuclear medicine physicians appointed by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), neuroradiologists appointed by the European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), and infectious diseases specialists appointed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), reviewed the literature from January 2006 to December 2015 and proposed 20 consensus statements in answer to clinical questions regarding SD diagnosis. The statements were graded by level of evidence level according to the 2011 Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine criteria and included in this consensus document for the diagnosis of SD in adults. The consensus statements are the result of literature review according to PICO (P:population/patients, I:intervention/indicator, C:comparator/control, O:outcome) criteria.

Evidence-based recommendations on the management of adult patients with SD, with particular attention to radiologic and nuclear medicine diagnosis, were proposed after a systematic review of the literature in the areas of nuclear medicine, radiology, infectious diseases, and microbiology.

Results

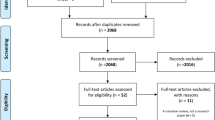

A diagnostic flow chart was developed based on the 20 consensus statements, scored by level of evidence according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine criteria.

Conclusions

This consensus document was developed with a final diagnostic flow chart for SD diagnosis as an aid for professionals in many fields, especially nuclear medicine physicians, radiologists, and orthopaedic and infectious diseases specialists.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Calderone RR, Larsen JM. Overview and classification of spinal infection. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:1–8.

Lazzeri E. Nuclear medicine imaging of vertebral infections: role of radiolabelled biotin. 2009.

Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65(Suppl 3):iii11–24.

Carragee EJ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:874–80.

Torda AJ, Gottlieb T, Bradbury R. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: analysis of 20 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:320–8.

Pigrau C, Almirante B, Flores X, et al. Spontaneous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis and endocarditis: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Am J Med. 2005;118(11):1287.

Sapico FL, Montgomerie JZ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: report of nine cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis. 1979;1:754–76.

Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Current concepts: osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:999–1007.

Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol. 1. Churchill Livingstone, 2000: 1182–1196.

Weissman S, Parker RD, Siddiqui W, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: retrospective review of 11 years of experience. Scand J Infect Dis. 2014;46(3):193–9.

Fantoni M, Trecarichi EM, Rossi B, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 2):2–7.

Cheung WY, Luk KD. Pyogenic spondylitis. Int Orthop. 2012;36(2):397–404.

Duarte RM, Vaccaro AR. Spinal infection: state of the art and management algorithm. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(12):2787–99.

Honan M, White GW, Eisenberg GM. Spontaneous infectious discitis in adults. Am J Med. 1996;100:85–9.

Chen HC, Tzaan WC, Lui TN. Spinal epidural abscesses: a retrospective analysis of clinical manifestations, sources of infection, and outcomes. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27(5):351–8.

Patzakis MJ, Rao S, Wilkins J, et al. Analysis of 61 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop. 1991:264, 178–183.

Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine. 2000;25(13):1668–79.

Legrand E, Flipo RM, Guggenbuhl P, et al. Management of nontuberculous infectious discitis. Treatments used in 110 patients admitted to 12 teaching hospitals in France. Joint Bone Spine. 2001;68:504–9.

Turunc T, Demiroglu YZ, Uncu H, et al. A comparative analysis of tuberculous, brucellar and pyogenic spontaneous spondylodiscitis patients. J Inf Secur. 2007;55:158–63.

Euba G, Narvaez JA, Nolla JM, et al. Long-term clinical and radiological magnetic resonance imaging outcome of abscess-associated spontaneous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis under conservative management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;38:28–40.

Colmenero JD, Jimenez-Mejias ME, Sanchez-Lora FJ, et al. Pyogenic, tuberculous, and brucellar vertebral osteomyelitis: a descriptive and comparative study of 219 cases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:709–15.

McHenry MC, Easley KA, Locker GA. Vertebral osteomyelitis: long-term outcome for 253 patients from 7 Cleveland-area hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1342–50.

Perronne C, Saba J, Behloul Z, et al. Pyogenic and tuberculous spondylodiskitis (vertebral osteomyelitis) in 80 adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:746–50.

Hershkovitz I, Donoghue HD, Minnikin DE, et al. Detection and molecular characterization of 9000-year-old mycobacterium tuberculosis from a Neolithic settlement in the eastern Mediterranean. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3426.

Perry M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein in the assessment of suspected bone infection – are they reliable indices? J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1996;41:116–8.

Yoon HJ, Song YG, Park WI, et al. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:453–61.

Trecarichi EM, Di Meco E, Mazzotta V, et al. Tuberculous spondylodiscitis: epidemiology, clinical features, treatment, and outcome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 2):58–72.

Ozuna RM, Delamarter RB. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis and postsurgical disc space infections. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:87–94.

Brown EM, Pople IK, de Louvois J, et al. Spine update: prevention of postoperative infection in patients undergoing spinal surgery. Spine. 2004;29:938–45.

Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, et al. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine. 2005;30:1460–5.

Richards BR, Emara KM. Delayed infections after posterior TSRH spinal instrumentation for idiopathic scoliosis: revisited. Spine. 2001;26:1990–6.

Levi AD, Dickman CA, Sonntag VK. Management of postoperative infections after spinal instrumentation. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:975–80.

Wimmer C, Gluch H. Franzreb M, et al. Predisposing factors for infection in spine surgery: a survey of 850 spinal procedures. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:124–8.

Massie JB, Heller JG, Abitbol JJ, et al. Postoperative posterior spinal wound infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):99–108.

Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, et al. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;39:10–7.

Berbari EF, Kanj SS, Kowalski TJ, et al. 2015 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of native vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(6):e26–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ482.

Jutte P, Lazzeri E, Sconfienza LM, et al. Diagnostic flowcharts in osteomyelitis, spondylodiscitis and prosthetic joint infection Q. J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;58(1):2–19.

Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine. www.cebm.net/finding-the-evidence-1-using-pico-to-formulate-a-search-question. website. 2016. Ref Type: Electronic Citation.

Felix SC, Mitchell JK. Diagnostic yield of CT-guided percutaneous aspiration procedures in suspected spontaneous infectious diskitis. Radiology. 2001;218:211–4.

Tyrell PN, Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW. Spinal infection. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:1066–77.

Tali ET. Spinal infections. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50(2):120–33.

Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, et al. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9(1):53–66.

Jevtic V. Vertebral infection. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(Suppl 3):E43–52.

Khoo LA, Heron C, Patel U, et al. The diagnostic contribution of the frontal lumbar spine radiograph in community referred low back pain-a prospective study of 1030 patients. Clin Radiol. 2003;58(8):606–9.

Leone A, Dell'Atti C, Magarelli N, et al. Imaging of spondylodiscitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 2):8–19.

Graham TS. The ivory vertebra sign. Radiology. 2005;235:614–5.

DeSanto J, Ross JS. Spine infection/inflammation. Radiol Clin N Am. 2011;49(1):105–27.

Tin BJ, Cassar-Pullicino VN. MR imaging of spinal infection. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2004;8(3):215–29.

Grane P, Josephsson A, Seferlis A, et al. Septic and aseptic post-operative discitis in the lumbar spine: evaluation by MR imaging. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:108–15.

Kawakyu-O'Connor D, Bordia R, Nicola R. Magnetic resonance imaging of spinal emergencies. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2016;24(2):325–44.

Tins BJ, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Lalam RK. Magnetic resonance of spinal infection. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;18(3):213–22.

Danchaivijitr N, Temram S, Thepmongkhol K, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MR imaging in tuberculous spondylitis. J Med Assoc Thail. 2007;90(8):1581–9.

Hong SH, Choi JY, Lee JW, et al. MR imaging assessment of the spine: infection or an imitation? Radiographics. 2009;29(2):599–612.

Cottle L, Riordan T. Infectious spondylodiscitis. J Inf Secur. 2008;56(6):401–12.

Kowalski TJ, Layton KF, Berbari EF, et al. Follow-up MR imaging in patients with pyogenic spine infections: lack of correlation with clinical features. Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(4):693–9.

Rauf F, Chaudhry UR, Atif M, et al. Spinal tuberculosis: our experience and a review of imaging methods. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28(5):498–503.

Go JL, Rothman S, Prosper A, et al. Spine infections. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2012;22(4):755–72.

Yang SC, Fu TS, Chen LH, et al. Identifying pathogens of spondylodiscitis: percutaneous endoscopy or CT-guided biopsy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(12):3086–92.

Brenac F, Huet H. Diagnostic accuracy of the percutaneous spinal biopsy. Optimization of the technique. J Neuroradiol. 2001;28(1):7–16.

Di Martino A, Papapietro N, Lanotte A, et al. Spondylodiscitis: standards of current treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(5):689–99.

Diehn FE. Imaging of spine infection. Radiol Clin N Am. 2012;50(4):777–98.

Sans N, Faruch M, Lapègue F, et al. Infections of the spinal column--spondylodiscitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93(6):520–9.

Dufour V, Feydy A, Rillardon L, et al. Comparative study of postoperative and spontaneous pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:766–71.

Enoch DA, Cargill JS, Laing R, et al. Value of CT-guided biopsy in the diagnosis of septic discitis. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:750–3.

Sehn JK, Gilula LA. Percutaneous needle biopsy in diagnosis and identification of causative organisms in cases of suspected vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:940–6.

Gasbarrini A, Boriani L, Salvadori C, et al. Biopsy for suspected spondylodiscitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 2):26–34.

Chaudhary SB, Vives MJ, Basra SK, et al. Postoperative spinal wound infections and postprocedural diskitis. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):441–51.

SPILF. [Primary infectious spondylitis, and following intradiscal procedure, without prosthesis. Short text]. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37(9):554–72.

Cebrián Parra JL, Saez-Arenillas Martín A, Urda Martínez-Aedo AL, et al. Management of infectious discitis. Outcome in one hundred and eight patients in a university hospital. Int Orthop. 2012;36(2):239–44.

Palestro CJ, Torres MA. Radionuclide imaging in orthopaedic infections. Semin Nucl Med. 1997;27:334–45.

Palestro CJ, Kim CK, Swyer AJ, et al. Radionuclide diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis: indium-111-leukocyte and technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate bone scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 1991;32:1861–5.

Devillers A, Moisan A, Jean S, et al. Technetium-99m hexamethyl-propylene amine oxime leucocyte scintigraphy for the diagnosis of bone and joint infections: a retrospective study in 116 patients. Eur J Nucl Med. 1995;22:302–7.

Coleman RE, Welch D. Possible pitfalls with clinical imaging of indium-111 leukocytes. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:122–5.

Fernandex-Ulloa M, Vasavada PJ, Hanslits ML, et al. Diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis: clinical, radiological and scintigraphic features. Orthopedics. 1985;8:1144–50.

Datz FL, Thorne DA. Cause and significance of cold bone defects on indium-111-labelled leukocyte imaging. J Nucl Med. 1987;28:820–3.

Whalen JL, Brown ML, McLeod R, et al. Limitations of indium leukocyte imaging for the diagnosis of spine infections. Spine. 1991;16:193–7.

Jacobson AF, Gilles CP, Cerqueira MD. Photopenic defects in marrow-containing skeleton on indium-111 leucocyte scintigraphy: prevalence at sites suspected of osteomyelitis and as an incidental finding. Eur J Nucl Med. 1992;19:858–64.

Prandini N, Lazzeri E, Rossi B, et al. Nuclear medicine imaging of bone infections. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27:633–44.

Concia E, Prandini N, Massari L, et al. Osteomyelitis: clinical update for practical guidelines. Nucl Med Commun. 2006;27(8):645–60.

Love C, Palestro CJ. Nuclear medicine imaging of bone infections. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:632–46.

Gratz S, Dorner J, Oestmann JW, et al. 67Ga-citrate and 99mTc-MDP for estimating the severity of vertebral osteomyelitis. Nucl Med Commun. 2000;21:111–20.

Fuster D, Solà O, Soriano A, et al. A prospective study comparing whole-body FDG PET/CT to combined planar bone scan with 67Ga SPECT/CT in the diagnosis of spondylodiskitis. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37:827–32.

Pauwels EKJ, Ribeiro MJ, Stoot JHMB, et al. FDG accumulation and tumor biology. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:317–22.

Kubota R, Yamada S, Kubota K, et al. Intratumoral distribution of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in vivo: high accumulation in macrophages and granulation tissues studied by microautoradiography. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1972–80.

Yamada S, Kubota K, Kubota R, et al. High accumulation of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in turpentine-induced inflammatory tissue. J Nucl Med. 36:1301–6.

Kaim AH, Weber B, Kurrer MO, et al. Autoradiographic quantification of 18F-FDG uptake in experimental soft-tissue abscesses in rats. Radiology. 2002;223:446–51.

Rosen RS, Fayad L, Wahl RL. Increased 18F-FDG uptake in degenerative disease of the spine: characterization with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1274–80.

S O, Suzuki M, Koshi T, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET for patients with suspected spondylitis showing Modic change. Spine. 2010;35(26):E1599–603.

Stumpe KD, Zanetti M, Weishaupt D, et al. FDG positron emission tomography for differentiation of degenerative and infectious endplate abnormalities in the lumbar spine detected on MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1151–7.

Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Suh KT, et al. Prediction of residual disease of spine infection using F-18 FDG PET/CT. Spine. 2009;34(22):2424–30.

Hungenbach S, Delank KS, Dietlein M, et al. 18-F fluorodeoxyglucose uptake pattern in patients with suspected spondylodiscitis. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:1068–74.

Nanni C, Boriani L, Salvadori C, et al. FDG PET/CT is useful for the interim evaluation of response to therapy in patients affected by haematogenous spondylodiscitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:1538–44.

Ito K, Kubota K, Morooka M, et al. Clinical impact of (18)F-FDG PET/CT on the management and diagnosis of infectious spondylitis. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31(8):691–8.

Riccio SA, Chu AK, Rabin HR, et al. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography interpretation criteria for assessment of antibiotic treatment response in pyogenic spine infection. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66(2):145–52.

Lee In S, Lee JS, Kim SJ, et al. Fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging in pyogenic and tuberculous spondylitis: preliminary study. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2009;33:587–92.

Stumpe KD, Dazzi H, Schaffner A, et al. Infection imaging using whole-body FDG-PET. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:822–32.

Kalicke T, Schmitz A, Risse JH, et al. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET in infectious bone diseases: results of histologically confirmed cases. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:524–8.

Schmitz A, Kalicke T, Willkomm P, et al. Use of fluorine-18 fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in assessing the process of tuberculous spondylitis. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:541–4.

Gratz S, Dorner J, Fischer U, et al. 18F-FDG hybrid PET in patients with suspected spondylitis. Eur J Nucl Med. 2002;29:516–24.

Zhuang H, Alavi A. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic imaging in the detection and monitoring of infection and inflammation. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:47–59.

De Winter F, Gemmel F, Van De Wiele C, et al. 18-fluorine fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for the diagnosis of infection in the postoperative spine. Spine. 2003;28:1314–9.

Mazzie JP, Brooks MK, Gnerre J. Imaging and management of postoperative spine infection. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2014;24(2):365–74.

Seifen T, Rettenbacher L, Thaler C, et al. Prolonged back pain attributed to suspected spondylodiscitis. The value of 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in the diagnostic work-up of patients. Nuklearmedizin. 2012;51:194–200.

Georgakopoulos A, Pneumaticos SG, Sipsas NV, et al. Positron emission tomography in spinal infections. Clin Imaging. 2015;39(4):553–8.

Ioannou S, Chatziioannou S, Pneumaticos SG, et al. Fluorine-18 fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scan contributes to the diagnosis and management of brucellar spondylodiskitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;7:13–73.

Bagrosky BM, Hayes KL, Koo PJ, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT evaluation of children and young adults with suspected spinal fusion hardware infection. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43(8):991–1000.

Dureja S, Sen IB, Acharya S. Potential role of F18 FDG PET-CT as an imaging biomarker for the noninvasive evaluation in uncomplicated skeletal tuberculosis: a prospective clinical observational study. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(11):2449–54.

Inanami H, Oshima Y, Iwahori T, et al. Role of 18F-fluoro-D-deoxyglucose PET/CT in diagnosing surgical site infection after spine surgery with instrumentation. Spine. 2015;40:109–13.

Dauchy FA, Dutertre A, Lawson-Ayayi S, et al. Interest of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography for the diagnosis of relapse in patients with spinal infection: a prospective study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(5):438–43.

Fuster D, Tomas X, Mayoral M, et al. Prospective comparison of whole-body 18F-FDG PET/CT and MRI of the spine in the diagnosis of haematogenous spondylodiskitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:264–71.

Skanjeti A, Penna D, Douroukas A, et al. PET in the clinical work-up of patients with spondylodiscitis: a new tool for the clinician? Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;56(6):569–76.

Sonmezoglu K, Sonmezoglu M, Halac M, et al. Usefulness of 99mTc-ciprofloxacin (Infecton) scan in diagnosis of chronic orthopedic infections: comparative study with 99mTc-HMPAO leukocyte scintigraphy. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:567–74.

Lazzeri E, Erba P, Perri M, et al. Scintigraphic imaging of vertebral osteomyelitis with 111In-biotin. Spine. 2008;33(7):E198–204. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816960c9.

Lazzeri E, Erba P, Perri M, et al. Clinical impact of SPECT/CT with In-111 biotin on the management of patients with suspected spine infection. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:12–7.

Gemmel F, Rijk PC, Collins JMP, et al. Expanding role of 18F-fluoro-d-deoxyglucose PET and PET/CT in spinal infections. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(4):540–51.

Kim CJ, Kang SJ, Yoon D, et al. Factors influencing culture positivity in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis patients with prior antibiotic exposure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(4):2470–3.

Zarrouk V, Feydy A, Sallès F, et al. Imaging does not predict the clinical outcome of bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(2):292–5.

Torrie PA, Leonidou A, Harding IJ, et al. Admission inflammatory markers and isolation of a causative organism in patients with spontaneous spinal infection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95(8):604–8.

Bhavan KP, Marschall J, Olsen MA, et al. The epidemiology of hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis: a cohort study in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:158.

Loibl M, Stoyanov L, Doenitz C, et al. Outcome-related co-factors in 105 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis in a tertiary care hospital. Infection. 2014;42(3):503–10.

D'Agostino C, Scorzolini L, Massetti AP, et al. A seven-year prospective study on spondylodiscitis: epidemiological and microbiological features. Infection. 2010;38(2):102–7.

Mete B, Kurt C, Yilmaz MH, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: eight years' experience of 100 cases. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(11):3591–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-2233-z.

Horasan ES, Colak M, Ersöz G, et al. Clinical findings of vertebral osteomyelitis: Brucella spp. versus other etiologic agents. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(11):3449–53.

Bettini N, Girardo M, Dema E, et al. Evaluation of conservative treatment of non specific spondylodiscitis. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(Suppl 1):143–50.

Kaya S, Ercan S, Kaya S, et al. Spondylodiscitis: evaluation of patients in a tertiary hospital. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8(10):1272–6.

Moromizato T, Harano K, Oyakawa M, et al. Diagnostic performance of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Intern Med. 2007;46(1):11–6.

Hamdan TA. Postoperative disc space infection after discectomy: a report on thirty-five patients. Int Orthop. 2012;36(2):445–50.

Ziu M, Dengler B, Cordell D, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary pyogenic spinal infections in intravenous recreational drug users. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(2):E3.

Hassoun A, Taur Y, Singer C. Evaluation of thin needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis and management of vertebral osteomyelitis (VO). Int J Infect Dis. 2006;10(6):486–7.

Eren Gök S, Kaptanoğlu E, Celikbaş A, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: clinical features and diagnosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):1055–60.

Park KH, Cho OH, Jung M, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis caused by gram-negative bacteria. J Inf Secur. 2014;69(1):42–50.

Luzzati R, Giacomazzi D, Danzi MC, et al. Diagnosis, management and outcome of clinically- suspected spinal infection. J Inf Secur. 2009;58(4):259–65.

Lora-Tamayo J, Euba G, Narváez JA, et al. Changing trends in the epidemiology of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: the impact of cases with no microbiologic diagnosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41(2):247–55.

Koslow M, Kuperstein R, Eshed I, et al. The unique clinical features and outcome of infectious endocarditis and vertebral osteomyelitis co-infection. Am J Med. 2014;127(7):669.e9–669.e15.

Urrutia J, Campos M, Zamora T, et al. Does pathogen identification influence the clinical outcomes in patients with pyogenic spinal infections? J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(7):E417–21.

Kim CJ, Song KH, Jeon JH, et al. A comparative study of pyogenic and tuberculous spondylodiscitis. Spine. 2010;35:E1096–100.

Kang SJ, Jang HC, Jung SI, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors of pyogenic spondylitis caused by gram-negative bacteria. PLoS One. 2015;10(5).

Aagaard T, Roed C, Dragsted C, et al. Microbiological and therapeutic challenges in infectious spondylodiscitis: a cohort study of 100 cases, 2006-2011. Scand J Infect Dis. 2013;45(6):417–24.

Fransen BL, de Visser E, Lenting A, et al. Recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Neth J Med. 2014;72(3):135–8.

Siemionow K, Steinmetz M, Bell G, et al. Identifying serious causes of back pain: cancer, infection, fracture. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75:557–66.

Fuursted K, Arpi M, Lindblad BE, et al. Broad-range PCR as a supplement to culture for detection of bacterial pathogens in patients with a clinically diagnosed spinal infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40(10):772–7.

Jensen AG, Espersen F, Skinhoj P, et al. Bacteremic Staphylococcus aureus spondylitis. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:509–17.

Pigrau C, Rodríguez-Pardo D, Fernández-Hidalgo N, et al. Health care associated hematogenous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: a severe and potentially preventable infectious disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(3):e365.

Corrah TW, Enoch DA, Aliyu SH, et al. Bacteraemia and subsequent vertebral osteomyelitis: a retrospective review of 125 patients. QJM. 2011;104(3):201–7.

Kim J, Kim YS, Peck KR, et al. Outcome of culture-negative pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: comparison with microbiologically confirmed pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:246–52.

Wang Z, Lenehan B, Itshayek E, et al. Primary pyogenic infection of the spine in intravenous drug users: a prospective observational study. Spine. 2012;37(8):685–92.

Lee A, Mirrett S, Reller LB, et al. Detection of bloodstream infections in adults: how many blood cultures are needed? J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:3546–8.

Colmenero JD, Ruiz-Mesa JD, Plata A, Bermúdez P, Martín-Rico P, Queipo-Ortuño MI, et al. Clinical findings, therapeutic approach, and outcome of brucellar vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(3):426–33.

Araj GF, Kattar MM, Fattouh LG, et al. Evaluation of the PANBIO Brucella immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for diagnosis of human brucellosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1334–5.

Koubaa M, Maaloul I, Marrakchi C, et al. Spinal brucellosis in south of Tunisia: review of 32 cases. Spine J. 2014;14(8):1538–44.

Bozgeyik Z, Ozdemir H, Demirdag K, et al. Clinical and MRI findings of brucellar spondylodiscitis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67(1):153–8.

Su SH, Tsai WC, Lin CY, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of spinal tuberculosis in southern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(4):291–300.

Mulleman D, Mammou S, Griffoul I, et al. Characteristics of patients with spinal tuberculosis in a French teaching hospital. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(4):424–7.

Menzies D, Pai M, Comstock G. Meta-analysis: new tests for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection: areas of uncertainty and recommendations for research. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:340–54.

Wu X, Ma Y, Li D, et al. Diagnostic value of ELISPOT technique for osteoarticular tuberculosis. Clin Lab. 2014;60(11):1865–70.

Cho OH, Park SJ, Park KH, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of a T-cell-based assay for osteoarticular tuberculosis. J Inf Secur. 2010;61(3):228–34.

Yuan K, Wu X, Zhang Q, et al. Enzyme-linked immunospot assay response to recombinant CFP-10/ESAT-6 fusion protein among patients with spinal tuberculosis: implications for diagnosis and monitoring of surgical therapy. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17(9):e733–8.

Yuan K, Zhong ZM, Zhang Q, et al. Evaluation of an enzyme-linked immunospot assay for the immunodiagnosis of atypical spinal tuberculosis (atypical clinical presentation/atypical radiographic presentation) in China. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17(5):529–37.

An HS, Seldomridge A. Spinal infections. Diagnostic tests and imaging studies. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;444:27–33.

Modic MT, Feiglin DH, Piraino DW, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: assessment using MR. Radiology. 1985;157:157–66.

Nakahara M, Ito M, Hattori N, et al. 18F-FDG-PET/CT better localizes active spinal infection than MRI for successful minimally invasive surgery. Acta Radiol. 2015;56(7):829–36.

Ledbetter LN, Salzman KL, Shah LM. Imaging psoas sign in lumbar spinal infections: evaluation of diagnostic accuracy and comparison with established imaging characteristics. Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(4):736–41.

Garg V, Kosmas C, Young PC, et al. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous biopsy for vertebral osteomyelitis: a department's experience. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(2):E10.

Raininko RK, Aho AJ, Laine MO. Computed tomography in spondylitis. CT versus other radiographic methods. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:372–7.

Che W, Li RY, Dong J. Progress in diagnosis and treatment of cervical postoperative infection. Orthop Surg. 2011;3(3):152–7.

Treglia G, Focacci C, Caldarella C, et al. The role of nuclear medicine in the diagnosis of spondylodiscitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(Suppl 2):20–5.

Chahoud J, Kanafani Z, Kanj SS. Surgical site infections following spine surgery: eliminating the controversies in the diagnosis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2014;7(1). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2014.00007.

Palestro CJ. Radionuclide imaging of osteomyelitis. Semin Nucl Med. 2015;45:32–46.

Gemmel F, Dumarey N, Palestro CJ. Radionuclide imaging of spinal infections. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:1226–37.

Guerado E, Cerván AM. Surgical treatment of spondylodiscitis. An update. Int Orthop. 2012;36:413–20.

Pupaibool J, Vasoo S, Erwin PJ, et al. The utility of image-guided percutaneous needle aspiration biopsy for the diagnosis of spontaneous vertebral osteomyelitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2015;15(1):122–31.

Fahnert J, Purz S, Javers J-S, et al. Use of simultaneous FDG-PET/MRI for the detection of spondylodiskitis. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1396–401.

Sehn JK. Gilula LA. Percutaneous needle biopsy in diagnosis and identification of causative organisms in cases of suspected vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur J Radio. 2012;81(1):940–6.

Mohanty SP, Bhat S, Nair NS. An analysis of clinicoradiological and histopathological correlation in tuberculosis of spine. J Indian Med Assoc. 2011;109(3):161–5.

Kornblum MB, Wesolowski DP, Fischgrund JS, et al. Computed tomography-guided biopsy of the spine. A review of 103 patients. Spine. 1998;23:81–5.

Babu NV, Titus VT, Chittaranjan S, et al. Computed tomographically guided biopsy of the spine. Spine. 1994;19:2436–42.

Peh W. CT-guided percutaneous biopsy of spinal lesions. Biomed Imaging Interv J. 2006;2:e25.

Yoon YK, Jo YM, Kwon HH, et al. Differential diagnosis between tuberculous spondylodiscitis and pyogenic spontaneous spondylodiscitis: a multicenter descriptive and comparative study. Spine J. 2015;15(8):1764–71.

Gras G, Buzele R, Parienti JJ, et al. Microbiological diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis: relevance of second percutaneous biopsy following initial negative biopsy and limited yield of post-biopsy blood cultures. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(3):371–5.

de Lucas EM, González Mandly A, Gutiérrez A, et al. CT-guided fine-needle aspiration in vertebral osteomyelitis: true usefulness of a common practice. Clin Rheumatol. 2009;28:315–20.

Watt JP, Davis JH. Percutaneous core needle biopsies: the yield in spinal tuberculosis. S Afr Med J. 2013;104(1):29–32.

Berk RH, Yazici M, Atabey N, et al. Detection of mycobacterium tuberculosis in formaldehyde solution-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue by polymerase chain reaction in Pott’s disease. Spine. 1996;21:1991–5.

Choi SH, Sung H, Kim SH, et al. Usefulness of a direct 16S rRNA gene PCR assay of percutaneous biopsies or aspirates for etiological diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(1):75–8.

Fenollar F, Roux V, Stein A, et al. Analysis of 525 samples to determine the usefulness of PCR amplification and sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene for diagnosis of bone and joint infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1018–28.

Levy PY, Fournier PE, Fenollar F, et al. Systematic PCR detection in culture-negative osteoarticular infections. Am J Med. 2013;126(12):1143.e25–33.

Al Dahouk S, Tomaso H, Nöckler K, et al. The detection of Brucella spp. using PCR-ELISA and real-time PCR assays. Clin Lab. 2004;50(7–8):387–94.

Navarro-Martinez A, Navarro E, Castano MJ, et al. Rapid diagnosis of human brucellosis by quantitative real-time PCR: a case report of brucellar spondylitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:385–7.

Lucio E, Adesokan A, Hadjipavlou AG, et al. Pyogenic spondylodiskitis: a radiologic/pathologic and culture correlation study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:712–6.

Chen SCA, Halliday CL, Meyer W. A review of nucleic acid-based diagnostic tests for systemic mycoses with an emphasis on polymerase chain reaction-based assays. Med Mycol. 2002;40:333–57.

Chang CY, Simeone FJ, Nelson SB, et al. Is biopsying the paravertebral soft tissue as effective as biopsying the disk or vertebral endplate? 10-year retrospective review of CT-guided biopsy of diskitis-osteomyelitis. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205(1):123–9.

Heyer CM, Brus LJ, Peters SA, et al. Efficacy of CT-guided biopsies of the spine in patients with spondylitis—an analysis of 164 procedures. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(3):e244–9.

Marschall J, Bhavan KP, Olsen MA, et al. The impact of prebiopsy antibiotics on pathogen recovery in hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):867–72.

Agarwal V, Wo S, Lagemann GM, et al. Image-guided percutaneous disc sampling: impact of antecedent antibiotics on yield. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:228–34.

Friedman JA, Maher CO, Quast LM, et al. Spontaneous disc space infections in adults. Surg Neurol. 2002;57(2):81–6.

Haaker RG, Senkal M, Kielich T, et al. Percutaneous lumbar discectomy in the treatment of lumbar discitis. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:98–101.

Ito M, Abumi K, Kotani Y, et al. Clinical outcome of posterolateral endoscopic surgery for pyogenic spondylodiscitis: results of 15 patients with serious comorbid conditions. Spine. 2007;32:200–6.

Jimenez-Mejias ME, de Dios Colmenero J, Sanchez-Lora FJ, et al. Postoperative spondylodiskitis: etiology, clinical findings, prognosis, and comparison with nonoperative pyogenic spondylodiskitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:339–45.

Niccoli Asabella A, Iuele F, Simone F, et al. Role of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of response to antibiotic therapy in patients affected by infectious spondylodiscitis. Hell J Nucl Med. 2015;18(Suppl 1):17–22.

Signore A, Jamar F, Israel O, et al. Clinical indications, image acquisition and data interpretation for white blood cells and anti-granulocyte monoclonal antibody scintigraphy: an EANM procedural guideline. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:1816–31.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the many people who contributed to this consensus document through active work on the document or simply by contributing with useful discussion. First of all, we thank the members of the previous EANM Committee on Infection and Inflammation (John Buscombe, Riddhika Chakravarrty, Paola Erba, Ora Israel, Francois Jamar, and Josè Martin-Comin) and the ESNR and ESCMID boards for supporting this work and disseminating our results in international congresses.

Each practice guideline, representing a strategic statement, has undergone a thorough consensus process as a result of an extensive review.

This document was brought to the attention of all other EANM committees and the European national societies of nuclear medicine. The comments and suggestions from the Oncology Committee and Physics Committee and from the Czech, Russian, German, Italian, Latvian and Belgian national societies are highly appreciated and have been considered for this consensus document.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure statements

The European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM), founded in 1985, is a professional nonprofit medical association that facilitates communication worldwide between individuals pursuing clinical and research excellence in nuclear medicine.

The European Society of Neuroradiology (ESNR), founded in 1977, is a professional society of European neuroradiologists and a leader in education and training, with courses including the brain, spine, and diagnostic neuroradiology, as well as a forum for professional development of European neuroradiology.

The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID), founded in 1983, is an influential component in the professional lives of microbiologists and infectious disease specialists around the world. ESCMID facilitates the advance of scientific knowledge and the dissemination of professional guidelines and consensus documents in the field of clinical microbiology and infectious diseases.

EANM, ESNR, and ESCMID members are physicians, biologists, technologists, and scientists specialising in the research and practice of nuclear medicine, neuroradiology, and infectious diseases, respectively.

This consensus paper, representing a policy statement by the EANM/ESNR (with ESCMID endorsement), has undergone a thorough consensus process in which an extensive review was performed. The EANM, ESNR, and ESCMID recognise that the safe and effective use of diagnostic imaging requires specific training, skills, and techniques, as described in the introduction section. Reproduction or modification of the published paper is not authorised.

They report what ideally should be done based on evidence from the literature. However, these recommendations should be carefully adapted to local practice, where not all diagnostic tests or imaging modalities may be available. Resources available to care for patients, as well as legislation and local regulations, may vary greatly from one European country to another.

The recommendations contained herein are intended as an educational tool to assist practitioners in providing appropriate care for patients. They are not inflexible rules or requirements of practice and are not intended, nor should they be used, to establish a legal standard of care. For these reasons and those set forth below, the EANM, ESNR, and ESCMID caution against the use of these recommendations in litigation in which the clinical decisions of a practitioner are called into question.

The ultimate judgement regarding the propriety of any specific procedure or course of action must be made by the physician or medical physicist in light of all the circumstances presented. A conscientious practitioner may responsibly adopt a course of action different from that set forth in this document when such course of action is indicated by the condition of the patient, limitations of available resources, or advances in knowledge or technology subsequent to publication of these recommendations.

The practice of medicine includes the prevention, diagnosis, alleviation, and treatment of disease. The variety and complexity of human conditions make it impossible to always reach the most appropriate diagnosis or to predict with certainty a particular response to treatment. Therefore, it should be recognised that adherence to these guidelines will not ensure an accurate diagnosis or a successful outcome. All that should be expected is that the practitioner will follow a reasonable course of action based on current knowledge (evidence-based medicine), available resources, and the needs of the patient to deliver effective and safe medical care. The sole purpose of this document is, therefore, to assist practitioners in achieving this objective.

The EANM and ESNR (with ESCMID endorsement) will periodically define new guidelines for the diagnosis of spine infection in adults to improve the quality of service to patients throughout the world. Existing diagnostic guidelines will be reviewed for revision or renewal, as appropriate, on their fifth anniversary or sooner, if indicated.

Conflict of interest

Elena Lazzeri is a senior advisor of the EANM Committee on Inflammation and Infection. She has nothing to declare.

Alessandro Bozzao has nothing to declare.

Maria Adriana Cataldo has nothing to declare.

Nicola Petrosillo has nothing to declare.

Luigi Manfrè has nothing to declare.

Andrej Trampuz has nothing to declare.

Alberto Signore is a senior advisor of the EANM Committee on Inflammation and Infection. He has nothing to declare.

Mario Muto has nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

This consensus document does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. The human studies described herein have been published previously.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Oncology – Brain.

Appendix

Appendix

Consensus statements

-

1)

SD should be suspected in patients with new or worsening spine pain and/or new myelo-radicular symptoms, and at least one of the following: fever, elevated ESR or CRP, bloodstream infection, or infective endocarditis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 28.

-

2)

CRP, ESR, and WBC counts should always be performed in patients with suspected SD.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 28.

-

3)

Blood cultures (for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria) should always be performed in patients with suspected SD.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 30.

-

4)

For patients with suspected SD and epidemiological risk factors for brucellosis, specific serological tests should be performed.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 6.

-

5)

For patients with suspected SD and risk factors for Mycobacterium tuberculosis , a PPD test and an interferon-γ release assay should be performed.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 8.

-

6)

Plain film X-ray should always be performed in patients with suspicion of spine infection for purposes of differential diagnostic and follow-up.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: radiography OR x-ray OR radiographic diagnosis OR digital radiography OR plain radiography = 497487.

C: none.

O: early diagnosis = 150145.

All papers found: 200.

Included papers for thorough reading: 6.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 6.

-

7)

In haematogenous SD, the first diagnostic imaging modality is MRI, if patients have no specific contraindications.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: magnetic resonance OR MR OR MRI = 392979.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5623.

All papers found: 1545.

Included papers for thorough reading: 6.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 5.

-

8)

MRI must be performed with T1, T2, and T2 fat-suppressed or STIR sequences without and with contrast medium with T1 fat suppression technique.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: MRI must be performed with T1, T2, and T2 fat-suppressed or STIR sequences without and with contrast medium with T1 fat-suppressed technique = 25.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5623.

All papers found: 8.

Included papers for thorough reading: 8.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 8.

-

9)

MRI in suspected spine infection should be performed with at least a 1.5 Tesla magnet.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: MRI must be performed with a 1.5 Tesla magnet = none.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5623.

All papers found: 4.

Included papers for thorough reading: 4.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 4.

-

10)

CT may be useful for diagnosis only when MRI is contraindicated, not available, or equivocal.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: CT OR computed tomography OR CeT = 324788.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5623.

All papers found: 5.

Included papers for thorough reading: 5.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 5.

-

11)

In primary and post-surgical SD, if MRI is contraindicated, the imaging modality of choice is [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

Contraindications to MRI = 120 (none on SD).

I: PET OR PET/CT OR FDG-PET OR fluorodeoxyglucose OR FDG OR positron emission tomography = 62923.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5377.

All papers found: 94.

Included papers for thorough reading: 30.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 24.

-

12)

In post-surgical SD, with or without spinal hardware, [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT can detect both spine infection and soft tissue infection.

P: post-surgical spine infection OR post-surgical vertebral infection OR post-surgical vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine OR post-surgical spondylodiscitis OR spinal hardware = 9683.

I: FDG-PET OR PET OR fluorodeoxyglucose OR FDG OR positron emission tomography OR PET/CT = 62923.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5377.

All papers found: 2.

Included papers for thorough reading: 12.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 10.

-

13)

In patients with suspected spine infection and elevated ESR and/or CRP and doubtful MRI, [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT should be performed.

P: inconclusive MR OR doubtful MR OR not diagnostic MR OR inconclusive MRI OR doubtful MRI OR no diagnostic MRI = 23502.

P: spine infection and elevated ESR and/or CRP = 23299.

I: FDG-PET OR PET OR fluorodeoxyglucose OR FDG OR positron emission tomography OR PET/CT = 62923.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5377.

All papers found: 18.

Included papers for thorough reading: 18.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 17.

-

14)

In patients with suspected spine infection, elevated ESR and/or CRP, doubtful or unperformable MRI, and doubtful or unperformable [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT, a CT scan should be performed with an image-guided biopsy.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: Inconclusive FDG-PET OR PET OR inconclusive fluorodeoxyglucose OR inconclusive FDG OR inconclusive positron emission tomography OR inconclusive PET/CT OR doubtful FDG-PET OR doubtful PET/CT =47758.

C: none.

O: CT-guided vertebral biopsy OR vertebral biopsy = 23943.

All papers found: 30.

Included papers for thorough reading: 7.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 7.

-

15)

The role of hybrid PET/MRI, although promising, needs to be evaluated.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: PET/MRI OR PET/MR OR hybrid PET/MRI OR hybrid PET/MR = 949.

C: none.

O: diagnosis of spine infection OR diagnosis of vertebral osteomyelitis OR diagnosis of vertebral infection OR diagnosis of soft tissue infection OR diagnosis of paravertebral soft tissue infection = 5377.

All papers found: none.

Included papers for thorough reading: none.

Included papers evidence-based statement: none.

-

16)

In case of negative MRI or negative [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT, the diagnosis of SD should be excluded.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: negative FDG-PET OR negative PET OR negative fluorodeoxyglucose OR negative FDG OR negative positron emission tomography OR negative PET/CT = 5800.

negative MR OR negative MRI OR negative magnetic resonance = 18549.

C: none.

O: absence of spine infection OR absence of vertebral infection OR absence of spondylodiscitis = 131.

All papers found: 5.

Included papers for thorough reading: 3.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 3.

-

17)

An image-guided aspiration biopsy should be performed in all patients with suspected SD based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 28.

-

18)

Antibiotic therapy should be discontinued or postponed before biopsy.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 9.

-

19)

In patients with suspected SD based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging studies and a negative biopsy (histology and microbiology), another biopsy should be done.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis.

I: diagnostic methods.

C: none.

O: diagnosis.

All papers found: 2289.

Included papers for thorough reading: 183.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 11.

-

20)

In patients with SD diagnosed by [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT, a second [ 18 F]FDG-PET/CT scan should be performed to evaluate the response to antibiotic therapy.

P: spine infection OR spinal infection OR vertebral infection OR vertebral osteomyelitis OR post-surgical spine infection OR spondylodiscitis OR discitis OR infectious spondylitis = 9683.

I: FDG-PET OR PET OR fluorodeoxyglucose OR FDG OR positron emission tomography OR PET/CT = 62923.

C: none.

O: response to therapy OR treatment response OR antibiotic response = 416536.

All papers found: 19.

Included papers for thorough reading: 9.

Included papers evidence-based statement: 8.

Statements 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 18, 19, 20 (ESCMID)

(((“spine”[MeSH Terms] OR “spine”[All Fields] OR “vertebral”[All Fields]) AND (“osteomyelitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “osteomyelitis”[All Fields])) OR (spinal[All Fields] AND (“osteomyelitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “osteomyelitis”[All Fields])) OR (“discitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “discitis”[All Fields] OR “spondylodiscitis”[All Fields]) OR (“discitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “discitis”[All Fields] OR “spondylodiskitis”[All Fields]) OR (“discitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “discitis”[All Fields] OR “diskitis”[All Fields]) OR (“discitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “discitis”[All Fields]) OR (infectious[All Fields] AND (“spondylitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “spondylitis”[All Fields])) OR (septic[All Fields] AND (“spondylitis”[MeSH Terms] OR “spondylitis”[All Fields])) OR (spinal[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields])) OR (spinal[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields] OR “infections”[All Fields])) OR ((“spine”[MeSH Terms] OR “spine”[All Fields]) AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields])) OR ((“spine”[MeSH Terms] OR “spine”[All Fields]) AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields] OR “infections”[All Fields])) OR ((“spine”[MeSH Terms] OR “spine”[All Fields] OR “vertebral”[All Fields]) AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields])) OR ((“spine”[MeSH Terms] OR “spine”[All Fields] OR “vertebral”[All Fields]) AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields] OR “infections”[All Fields])) OR (disk[All Fields] AND space[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields])) OR (disk[All Fields] AND space[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields] OR “infections”[All Fields])) OR (disc[All Fields] AND space[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields])) OR (disc[All Fields] AND space[All Fields] AND (“infection”[MeSH Terms] OR “infection”[All Fields] OR “infections”[All Fields]))) AND ((“diagnosis”[Subheading] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms]) OR (“diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnostic”[All Fields])) AND ((“2006/01/01”[PDAT]: “2015/12/31”[PDAT]) AND “humans”[MeSH Terms] AND English[lang] AND “adult”[MeSH Terms]) NOT (“case reports”[Publication Type] OR “case reports”[All Fields])

All papers found: 2289. Included papers for thorough reading: 183. Included papers evidence-based statement: 61.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lazzeri, E., Bozzao, A., Cataldo, M.A. et al. Joint EANM/ESNR and ESCMID-endorsed consensus document for the diagnosis of spine infection (spondylodiscitis) in adults. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 46, 2464–2487 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04393-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-019-04393-6