Abstract

For higher-order (process) languages, characterising contextual equivalence is a long-standing issue. In the setting of a higher-order \(\pi \)-calculus with session types, we develop characteristic bisimilarity, a typed bisimilarity which fully characterises contextual equivalence. To our knowledge, ours is the first characterisation of its kind. Using simple values inhabiting (session) types, our approach distinguishes from untyped methods for characterising contextual equivalence in higher-order processes: we show that observing as inputs only a precise finite set of higher-order values suffices to reason about higher-order session processes. We demonstrate how characteristic bisimilarity can be used to justify optimisations in session protocols with mobile code communication.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Context In higher-order process calculi communicated values may contain processes. Higher-order concurrency has received significant attention from untyped and typed perspectives; see, e.g., [13, 15, 20, 26, 30, 33]. In this work, we consider \(\textsf {HO}\pi \), a higher-order process calculus with session communication: it combines functional constructs (abstractions/applications, as in the call-by-value \(\lambda \)-calculus) and concurrent primitives (synchronisation on shared names, communication on linear names, recursion). By amalgamating functional and concurrent constructs, \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) may specify complex session protocols that include both first-order communication (name passing) and higher-order processes (process passing) and that can be type-checked using session types [9]. By enforcing shared and linear usage policies, session types ensure that each communication channel in a process specification conforms to its prescribed protocol. In session-based concurrency, distinguishing between shared and linear names is important, for computation conceptually involves two distinct phases: the first one is non-deterministic and uses shared names, as it represents the interaction of processes seeking compatible protocol partners; the second phase proceeds deterministically along linear names, as it specifies the concurrent execution of the session protocols established in the first phase.

Although models of higher-order concurrency with session communication have been already developed (cf. works by Mostrous and Yoshida [25] and by Gay and Vasconcelos [5]), their behavioural equivalences remain little understood. Clarifying the status of these equivalences is essential to, e.g., justify non-trivial optimisations in protocols involving both name and process passing. An important aspect in the development of these typed equivalences is that typed semantics are usually coarser than untyped semantics. Indeed, since (session) types limit the contexts (environments) in which processes can interact, typed equivalences admit stronger properties than their untyped counterpart.

The form of contextual equivalence typically used in concurrency is barbed congruence [10, 24]. A well-known behavioural equivalence for higher-order processes is context bisimilarity [31]. This is a characterisation of barbed congruence that offers an adequate distinguishing power at the price of heavy universal quantifications in output clauses. Obtaining alternative characterisations of context bisimilarity is thus a recurring, important problem for higher-order calculi—see, e.g., [13, 15, 21, 30, 31, 34]. In particular, Sangiorgi [30, 31] has given characterisations of context bisimilarity for higher-order processes; such characterisations, however, do not scale to calculi with recursive types, which are essential to express practical protocols in session-based concurrency. A characterisation that solves this limitation was developed by Jeffrey and Rathke [13]; their solution, however, does not consider linearity which, as explained above, is an important aspect in session-based concurrency.

This work Building upon [13, 30, 31], our discovery is that linearity as induced by session types plays a vital rôle in solving the open problem of characterising context bisimilarity for higher-order mobile processes with session communication. Our approach is to exploit the coarser semantics induced by session types to limit the behaviour of higher-order session processes. Indeed, the use of session typed contexts (i.e., environments disciplined by session types) leads to process semantics that admit stronger properties than untyped semantics. Formally, we enforce this limitation in behaviour by defining a refined labelled transition system (LTS) which effectively narrows down the spectrum of allowed process behaviours, exploiting elementary processes inhabiting session types. We then introduce characteristic bisimilarity: this new notion of typed bisimilarity is more tractable than context bisimilarity, in that it relies on the refined LTS for input actions and, more importantly, does not appeal to universal quantifications on output actions.

Our main result is that characteristic bisimilarity coincides with context bisimilarity. Besides confirming the value of characteristic bisimilarity as a useful reasoning technique for higher-order processes with sessions, this result is remarkable also from a technical perspective, for associated completeness proofs do not require operators for name matching, in contrast to Jeffrey and Rathke’s technique for higher-order processes with recursive types [13].

Outline Next, we informally overview the key ideas of characteristic bisimilarity, our characterisation of contextual equivalence. Then, Sect. 3 presents the session calculus \(\textsf {HO}\pi \). Section 4 gives the session type system for \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) and states type soundness. Section 5 develops characteristic bisimilarity and states our main result: characteristic bisimilarity and contextual equivalence coincide for well-typed \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes (Theorem 2). Section 6 discusses related works, while Sect. 7 collects some concluding remarks.

This paper is a revised, extended version of the conference paper [16]. This presentation includes full technical details—definitions and proofs, collected in Appendices 1 and 2. In particular, we introduce higher-order bisimilarity (an auxiliary labelled bisimilarity) and highlight its rôle in the proof of Theorem 2. We also elaborate further on the use case scenario for characteristic bisimilarity given in [16] (the Hotel Booking scenario). Using an additional example, given in Sect. 6, we compare our approach with Jeffrey and Rathke’s [13]. Moreover, we offer extended discussions of related works.

2 Overview: characteristic bisimulations

We explain how we exploit session types to define characteristic bisimilarity. Key notions are triggered and characteristic processes/values. We first informally introduce some basic notation and terminology; formal definitions will be given in Sect. 3.

Preliminaries The syntax of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) considered in this paper is given below. We write n to range over shared names \(a,b,\ldots \) and \(s, {s}', \ldots \) to range over session (linear) names. Also, u, w denotes a name or a name variable. Session names are sometimes called endpoints. We consider a notion of duality on names, particularly relevant for session names: we shall write \(\overline{s}\) to denote the dual endpoint of s.

Hence, the higher-order character of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) comes from the fact that values exchanged in synchronisations include abstractions.

The semantics of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) can be given in terms of a labelled transition system (LTS), denoted \(P \xrightarrow {\ell } P'\), where \(\ell \) denotes a transition label or the internal action \(\tau \). This way, for instance, \(P \xrightarrow {n ?\langle V \rangle } P'\) denotes an input transition (a value V received along n) and \(P \xrightarrow {(\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V \rangle } P'\) denotes an output transition (a value V emitted along n, extruding names \(\widetilde{m}\)). Weak transitions, written \(P \mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{\ell } P'\), abstract from internal actions in the usual way. Throughout the paper, we write \(\mathfrak {R}, \mathfrak {R}',\ldots \) to denote binary relations on (typed) processes.

\(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes specify structured communications (protocols) as disciplined by session types, denoted \(S, S', \ldots \), which we informally describe next:

As we will see, type U denotes first-order values (i.e., shared and session names) but also shared and linear functional types, denoted \(U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \) and \(U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \), respectively, where \(\diamond \) is the type for processes.

Issues of context bisimilarity Context bisimilarity (denoted \(\approx \), cf. Definition 12) is an overly demanding relation on higher-order processes. It is far from satisfactory due to two issues, associated to demanding clauses for output and input actions. A first issue is the universal quantification in the output clause of context bisimilarity. Suppose \(P \,\mathfrak {R}\, Q\), for some context bisimulation \(\mathfrak {R}\). We have the following clause:

-

\((\star )\) Whenever \(P \xrightarrow {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1}) n !\langle V \rangle } P'\) there exist \(Q'\), W such that \(Q \mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2}) n !\langle W \rangle } Q'\) and,

for all R with \(\texttt {fv}(R)=\{x\}\), \((\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P' \;|\;RV/x) \,\mathfrak {R}\, (\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q' \;|\;RW/x)\).

Intuitively, process R above stands for any possible context to which the emitted value (V and W) is supposed to go. (As usual, \(RV/x\) denotes the capture-avoiding substitution of V for x in process R.) As explained in [31], considering all possible contexts R is key to achieve an adequate distinguishing power.

The second issue is due to inputs, and follows from the fact that we work with an early labelled transition system (LTS). Thus, an input prefix may observe infinitely many different values.

To alleviate these issues, in characteristic bisimilarity (denoted \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\), cf. Definition 18) we take two (related) steps:

-

(a)

We replace \((\star )\) with a clause involving a context more tractable than \(RV/x\) (and \(RW/x\)); and

-

(b)

We refine inputs to avoid observing infinitely many actions on the same input prefix.

Trigger processes To address (a), we exploit session types. We first observe that, for any V, process \(RV/x\) in \((\star )\) is context bisimilar to the process

In fact, through a name application and a synchronisation on session endpoint s we do have \(P \approx RV/x\):

where it is worth noticing that application and endpoint synchronisations are deterministic.

Now let us consider process \(T_{V}\) below, where t is a fresh name:

If \(T_{V}\) inputs value \(\lambda z.\,z ?(x) . R\) then we have:

Processes such as \(T_{V}\) offer a value at a fresh name; this class of trigger processes already suggests a tractable formulation of bisimilarity without the demanding output clause \((\star )\). Process \(T_{V}\) in (1) requires a higher-order communication along t. As we explain below, we can give an alternative trigger process; the key is using elementary inhabitants of session types.

Characteristic processes and values To address (b), we limit the possible input values (such as \(\lambda z.\,z ?(x) . R\) above) by exploiting session types. The key concept is that of characteristic process/value of a type, i.e., a simple process term that inhabits that type (Definition 13). To illustrate the key idea underlying characteristic processes, consider the session type

which abstracts a protocol that first inputs an abstraction (i.e., a function from values \(S_1\) to processes), and then outputs a value of type \(S_2\). Let P be the process \(u ?(x) . (u !\langle s_2 \rangle . \mathbf {0}\;|\;x\, {s_1})\), where \(s_1, s_2\) are fresh names. It can be shown that P inhabits session type S; for the purposes of the behavioural theory developed in this paper, process P will serve as a kind of characteristic (representative) process for S along name u.

Given a session type S and a name u, we write \([\!\!(S)\!\!]^{u} \) for the characteristic process of S along u. Also, given a value type U (i.e., a type for channels or abstractions), we write \([\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}}\) to denote its characteristic value (cf. Definition 13). As we explain next, we use \([\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}}\) to refine input transitions.

Refined input transitions To refine input transitions, we need to observe an additional value, \(\lambda {x}.\,t ?(y) . (y\, {{x}})\), called the trigger value (cf. Definition 14). This is necessary: it turns out that a characteristic value alone as the observable input is not enough to define a sound bisimulation (cf. Example 5). Intuitively, the trigger value is used to observe/simulate application processes.

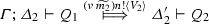

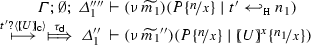

Based on the above discussion, we define an alternative LTS on typed processes, denoted  . We use this refined LTS to define characteristic bisimulation (Definition 18), in which the demanding clause \((\star )\) is replaced with a more tractable output clause based on characteristic trigger processes (cf. (2) below). Key to this alternative LTS is the following (refined) transition rule for input actions (cf. Definition 15) which, roughly speaking, given some fresh t, only admits names m, trigger values \(\lambda {x}.\,t ?(y) . (y\, {{x}})\), and characteristic values \([\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}}\):

. We use this refined LTS to define characteristic bisimulation (Definition 18), in which the demanding clause \((\star )\) is replaced with a more tractable output clause based on characteristic trigger processes (cf. (2) below). Key to this alternative LTS is the following (refined) transition rule for input actions (cf. Definition 15) which, roughly speaking, given some fresh t, only admits names m, trigger values \(\lambda {x}.\,t ?(y) . (y\, {{x}})\), and characteristic values \([\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}}\):

Note the different notation for standard and refined transitions: \(\xrightarrow {n ?\langle V \rangle }\) vs.  .

.

Characteristic triggers Following the same reasoning as (1), we can use an alternative trigger process, called characteristic trigger process, to replace clause (\(\star \)). Given a fresh name t and a value V of with type U, we have:

This formulation is justified, because given \(T_V\) as in (1), we may show that

Thus, unlike process (1), the characteristic trigger process in (2) does not involve a higher-order communication on t. In contrast to previous approaches [13, 30] our characteristic trigger processes do not use recursion or replication. This is key to preserve linearity of session endpoints.

It is also noteworthy that \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) lacks name matching, which is crucial in [13] to prove completeness of bisimilarity. The lack of matching operators is compensated here with the use of (session) types. Matching gives the observer the ability to test the equality of received names. In contrast, in our theory a process trigger embeds a name into a characteristic process so as to observe its (typed) behaviour. Thus, equivalent processes deal with (possibly different) names that have the same (typed) behaviour.

3 A higher-order session \(\pi \)-calculus

We introduce the higher-order session \(\pi \)-calculus (\(\textsf {HO}\pi \)) which, as hinted at above, includes both name and abstraction passing, shared and session communication, as well as recursion; it is essentially the language proposed in [25], where a behavioural theory is not developed.

3.1 Syntax

The syntax of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) is defined in Fig. 1a. We use \(a,b,c, \dots \) to range over shared names and \(s, \overline{s}, \dots \) to range over session names. We use \(n, m, t, \dots \) for session or shared names. Intuitively, session names represent deterministic communication endpoints, while shared names represent non-deterministic points. We define the dual operation over names n as \(\overline{n}\) with \(\overline{\overline{s}} = s\) and \(\overline{a} = a\). This way, e.g., session names s and \(\overline{s}\) are two dual endpoints. Name variables are denoted with \(x, y, z, \dots \), and recursive variables are denoted with \(X, Y, \dots \). Values V, W include name identifiers \(u, v, \ldots \) (first-order values) and abstractions \(\lambda x.\,P\) (higher-order values), where P is a process P and x is a name parameter.

Process terms include usual \(\pi \)-calculus constructs for sending and receiving values V: process \(u !\langle V \rangle . P\) denotes the output of V over name u, with continuation P, while process \(u ?(x) . P\) denotes the input prefix on name u of a value that will substitute variable x in the continuation P. Recursion is expressed by \(\mu X. P\), which binds the recursive variable \(X\) in process P. Process \(V\, {W}\) represents the application of abstraction V to value W. Typing ensures that V is not a name. In the spirit of session-based \(\pi \)-calculi [9], we consider processes \(u \triangleright \{l_i: P_i\}_{i \in I}\) and \(u \triangleleft l . P\) to define labelled choice: given a finite index set I, process \(u \triangleright \{l_i: P_i\}_{i \in I}\) offers a choice among processes with pairwise distinct labels; process \(u \triangleleft l . P\) selects label l on name u and then behaves as P. Constructs for inaction \(\mathbf {0}\) and parallel composition \(P_1 \;|\;P_2\) are standard. Name restriction \((\nu \, n) P\) is also as customary; we notice that restriction for session names \((\nu \, s) P\) simultaneously binds endpoints s and \(\overline{s}\) in P.

We use \(\texttt {fv}(P)\) and \(\texttt {fn}(P)\) to denote the sets of free variables and names in P, respectively. In a statement, we will say that a name is fresh if it is not among the names of the objects (processes, actions, etc.) of the statement. We assume that V in \(u !\langle V \rangle .{P}\) does not include free recursive variables \(X\). If \(\texttt {fv}(P) = \emptyset \), we call P closed.

3.2 Semantics

Figure 1c defines the operational semantics of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \), given as a reduction relation that relies on a structural congruence relation, denoted \(\equiv \) (Fig. 1b): it includes a congruence that ensures the consistent renaming of bound names, denoted \(\equiv _\alpha \). We assume the expected extension of \(\equiv \) to values V. Reduction is denoted \(\longrightarrow \); some intuitions on the rules in Fig. 1 follow. Rule \({{[\text {App}]}}\) defines value application. Rule \({{[\text {Pass}]}}\) defines an interaction/synchronization at n; it can be on a shared name (with \(\overline{n}=n\)) or a session endpoint. Rule \({{[\text {Sel}]}}\) is the standard rule for labelled choice/selection [9]: given a finite index set I, a process selects label \(l_j\) on name n over a pairwise distinct set of labels \(\{l_i\}_{i \in I}\) offered by a branching on the dual endpoint \(\overline{n}\); as a result, process \(P_j\) is selected, and the remaining alternatives are discarded. Other rules are standard. We write \(\longrightarrow ^*\) for a multi-step reduction.

3.3 An example: the hotel booking scenario

To illustrate \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) and its expressive power, let us consider a usecase scenario that adapts the example given by Mostrous and Yoshida [25, 26]. The scenario involves a \(\textsf {Client}\) process that wants to book a hotel room. \(\textsf {Client}\) narrows the choice down to two hotels, and requires a quote from the two in order to decide. The round-trip time (RTT) required for taking quotes from the two hotels in not optimal, so the client sends mobile processes to both hotels to automatically negotiate and book a room.

We now present two \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) implementations of this scenario. For convenience, we write \(\texttt {if}\ e\ \texttt {then}\ (P_1\ \varvec{;} \ P_2)\) to denote a conditional process that executes \(P_1\) or \(P_2\) depending on boolean expression e (encodable using labelled choice). The first implementation is as follows:

Process \(\textsf {Client}_1\) sends two abstractions with body \(P_{xy}\), one to each hotel, using sessions \(s_1\) and \(s_2\). That is, \(P_{xy}\) is the mobile code with free names x, y: while name x is meant to be instantiated by the hotel as the negotiating endpoint, name y is used to interact with \(\textsf {Client}_1\). Intuitively, process \(P_{xy}\):

-

(i)

sends the room requirements to the hotel;

-

(ii)

receives a quote from the hotel;

-

(iii)

sends the quote to \(\textsf {Client}_1\);

-

(iv)

expects a choice from \(\textsf {Client}_1\) whether to accept or reject the offer;

-

(v)

if the choice is \(\textsf {accept}\) then it informs the hotel and performs the booking; otherwise, if the choice is \(\textsf {reject}\) then it informs the hotel and ends the session.

\(\textsf {Client}_1\) instantiates two copies of \(P_{xy}\) as abstractions on session x. It uses two fresh endpoints \(h_1, h_2\) to substitute channel y in \(P_{xy}\). This enables communication with the mobile code(s). In fact, \(\textsf {Client}_1\) uses the dual endpoints \(\overline{h_1}\) and \(\overline{h_2}\) to receive the negotiation result from the two remote instances of P and then inform the two processes for the final booking decision.

We present now a second implementation in which the two mobile processes reach an agreement by interacting with each other (rather than with the client):

Processes \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) negotiate a quote from the hotel in the same fashion as process \(P_{xy}\) in \(\textsf {Client}_1\). The key difference with respect to \(P_{xy}\) is that y is used for interaction between process \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\). Both processes send their quotes to each other and then internally follow the same logic to reach to a decision. Process \(\textsf {Client}_2\) then uses sessions \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) to send the two instances of \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) to the two hotels, using them as abstractions on name x. It further substitutes the two endpoints of a fresh channel h to channels y respectively, in order for the two instances to communicate with each other.

The different protocols implemented by \(\textsf {Client}_1\) and \(\textsf {Client}_2\) can be represented by the sequence diagrams of Fig. 2. We will assign session types to these processes in Example 1. Later on, in Sect. 5.9 we will show that \(\textsf {Client}_1\) and \(\textsf {Client}_2\) are behaviourally equivalent using characteristic bisimilarity; see Proposition 3.

Sequence diagrams for \(\textsf {Client}_1\) and \(\textsf {Client}_2\), as in Sect. 3.3

4 Types and typing

We define a session typing system for \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) and state its main properties. As we explain below, our system distils the key features of [25, 26].

4.1 Types

The syntax of types of \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) is given below:

Value types U include the first-order types C and the higher-order types L. Session types are denoted with S and shared types with \(\langle S \rangle \) and \(\langle L \rangle \). We write \(\diamond \) to denote the process type. The functional types \(U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \) and \(U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \) denote shared and linear higher-order types, respectively. Session types have the meaning already motivated in Sect. 2. The output type \(!\langle U \rangle ; S\) first sends a value of type U and then follows the type described by S. Dually, \(?(U) ; S\) denotes an input type. The selection type \(\oplus \{l_i:S_i\}_{i \in I}\) and the branching type \( { \& } \{l_i:S_i\}_{i \in I}\) define labelled choice, implemented at the level of processes by internal and external choice mechanisms, respectively. Type \(\texttt {end}\) is the termination type. We assume the recursive type \(\mu \textsf {t}.S\) is guarded, i.e., the type variable \(\textsf {t}\) only appears under prefixes. This way, e.g., the type \(\mu \textsf {t}.\textsf {t}\) is not allowed. The sets of free/bound variables of a session type S are defined as usual; the sole binder is \(\mu \textsf {t}.S\). Closed session types do not have free type variables.

Our type system is strictly included in that considered in [25, 26], which admits asynchronous communication and arbitrary nesting in functional types, i.e., their types are of the form \(U \multimap T\) (resp. \(U \rightarrow T\)), where T ranges over U and the process type \(\diamond \). In contrast, our functional types are of the form \(U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \) (resp. \(U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \)).

We rely on notions of duality and equivalence for types. Let us write \(S_1 \sim S_2\) to denote that \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) are type-equivalent (see Definition 21 in the Appendix). This notion extends to value types as expected; in the following, we write \(U_1 \sim U_2\) to denote that \(U_1\) and \(U_2\) are type-equivalent. We write \(S_1 \ \textsf {dual}\ S_2\) if \(S_1\) is the dual of \(S_2\). Intuitively, duality converts ! into ? and \(\oplus \) into & (and vice-versa). More formally, following [4], we have a co-inductive definition for type duality:

Definition 1

(Duality) Let \({\mathsf {S}}{\mathsf {T}}\) be a set of closed session types. Two types S and \(S'\) are said to be dual if the pair \((S,S')\) is in the largest fixed point of the monotone function \(F:{\mathcal {P}}({\mathsf {S}}{\mathsf {T}}\times {\mathsf {S}}{\mathsf {T}}) \rightarrow {\mathcal {P}}({\mathsf {S}}{\mathsf {T}}\times {\mathsf {S}}{\mathsf {T}})\) defined by:

Standard arguments ensure that F is monotone, thus the greatest fixed point of F exists. We write \(S_1 \ \textsf {dual}\ S_2\) if \((S_1,S_2)\in \mathfrak {R}\).

4.2 Typing environments and judgements

Typing environments are defined below:

Typing environments \(\varGamma \), \(\varLambda \), and \(\varDelta \) satisfy different structural principles. Intuitively, the exchange principle indicates that the ordering of type assignments does not matter. Weakening says that type assignments need not be used. Finally, contraction says that type assignments may be duplicated.

The environment \(\varGamma \) maps variables and shared names to value types, and recursive variables to session environments; it admits weakening, contraction, and exchange principles. While \(\varLambda \) maps variables to linear higher-order types, \(\varDelta \) maps session names to session types. Both \(\varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \) are only subject to exchange. The domains of \(\varGamma , \varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \) are assumed pairwise distinct.

Given \(\varGamma \), we write \(\varGamma \backslash x\) to denote the environment obtained from \(\varGamma \) by removing the assignment \(x:U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \), for some U. This notation applies similarly to \(\varDelta \) and \(\varLambda \); we write \(\varDelta \backslash \varDelta '\) (and \(\varLambda \backslash \varLambda '\)) with the expected meaning. Notation \(\varDelta _1\cdot \varDelta _2\) means the disjoint union of \(\varDelta _1\) and \(\varDelta _2\). We define typing judgements for values V and processes P:

While the judgement on the left says that under environments \(\varGamma \), \(\varLambda \), and \(\varDelta \) value V has type U; the judgement on the right says that under environments \(\varGamma \), \(\varLambda \), and \(\varDelta \) process P has the process type \(\diamond \). The type soundness result for \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) (Theorem 1) relies on two auxiliary notions on session environments:

Definition 2

(Session environments: balanced/reduction) Let \(\varDelta \) be a session environment.

-

\(\varDelta \) is balanced if whenever \(s: S_1, \overline{s}: S_2 \in \varDelta \) then \(S_1 \ \textsf {dual}\ S_2\).

-

We define the reduction relation \(\longrightarrow \) on session environments as:

$$ \begin{aligned} \varDelta \cdot s: !\langle U \rangle ; S_1 \cdot \overline{s}: ?(U) ; S_2\longrightarrow & {} \varDelta \cdot s: S_1 \cdot \overline{s}: S_2 \\ \varDelta \cdot s: \oplus \{l_i: S_i\}_{i \in I} \cdot \overline{s}: { \& } \{l_i: S_i'\}_{i \in I}\longrightarrow & {} \varDelta \cdot s: S_k \cdot \overline{s}: S_k' \ (k \in I) \end{aligned}$$

We rely on a typing system that is similar to the one developed in [25, 26]. The typing system is defined in Fig. 3. Rules \([{{\textsc {Sess}}]}\), \([{{\textsc {Sh}}]}\), \([{{\textsc {LVar}}]}\) are name and variable introduction rules. Rule \( {[{{\textsc {Prom}}]}}\) allows a value with a linear type \(U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \) to be used as \(U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \) if its linear environment is empty. Rule \( {[{{\textsc {EProm}}]}}\) allows to freely use a shared type variable in a linear way.

Abstraction values are typed with Rule \( {[{{\textsc {Abs}}]}}\). The key type for an abstraction is the type for the bound variable of the abstraction, i.e., for a bound variable with type C the corresponding abstraction has type \(C\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \). The dual of abstraction typing is application typing, governed by Rule \( {[{{\textsc {App}}]}}\): we expect the type U of an application value W to match the type \(U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \) or \(U\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond \) of the application variable x.

In Rule \( {[{{\textsc {Send}}]}}\), the type U of the sent value V should appear as a prefix on the session type \(!\langle U \rangle ; S\) of u. Rule \( {[{{\textsc {Rcv}}]}}\) is its dual. We use a similar approach with session prefixes to type interaction between shared names as defined in Rules \( {[{{\textsc {Req}}]}}\) and \( {[{{\textsc {Acc}}]}}\), where the type of the sent/received object (S and L, respectively) should match the type of the sent/received subject (\(\langle S \rangle \) and \(\langle L \rangle \), respectively). Rules \( {[{{\textsc {Sel}}]}}\) and \( {[{{\textsc {Bra}}]}}\) for selection and branching are standard: both rules prefix the session type with the selection type \(\oplus \{l_i: S_i\}_{i \in I}\) and \( { \& } \{l_i:S_i\}_{i \in I}\), respectively.

A shared name creation a creates and restricts a in environment \(\varGamma \) as defined in Rule \([{{\textsc {Res}}]}\). Creation of a session name s creates and restricts two endpoints with dual types in Rule \([{{\textsc {ResS}}]}\). Rule \([{{\textsc {Par}}]}\), combines the environments \(\varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \) of the parallel components of a parallel process. The disjointness of environments \(\varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \) is implied. Rule \([{{\textsc {End}}]}\) adds a name with type \(\texttt {end}\) in \(\varDelta \). The recursion requires that the body process matches the type of the recursive variable as in Rule \([{{\textsc {Rec}}]}\). The recursive variable is typed directly from the shared environment \(\varGamma \) as in Rule \([{{\textsc {RVar}}]}\). Rule \([{{\textsc {Nil}}]}\) says that the inactive process \(\mathbf {0}\) is typed with empty linear environments \(\varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \).

We state the type soundness result for \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes.

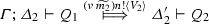

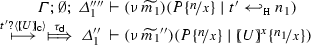

Theorem 1

(Type soundness) Suppose \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \) with \(\varDelta \) balanced. Then \(P \longrightarrow P'\) implies \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta ' \vdash P' \triangleright \diamond \) and \(\varDelta = \varDelta '\) or \(\varDelta \longrightarrow \varDelta '\) with \(\varDelta '\) balanced.

Proof

Following standard lines. See Appendix 1 for details. \(\square \)

Example 1

(The hotel booking example, revisited) We give types to the client processes of Sect. 3.3. Assume

While the typing for \(\lambda x.\,P_{xy}\) is \(\emptyset ; \emptyset ; y: S \vdash \lambda x.\,P_{xy} \triangleright U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \), the typing for \(\textsf {Client}_1\) is \(~~ \emptyset ; \emptyset ; s_1: !\langle U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\cdot s_2: !\langle U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\vdash \textsf {Client}_1 \triangleright \diamond \).

The typings for \(Q_1\) and \(Q_2\) are \( \emptyset ; \emptyset ; y: !\langle \textsf {quote} \rangle ; ?(\textsf {quote}) ; \texttt {end}\vdash \lambda x.\,Q_i \triangleright U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \) (\(i=1,2\)) and the type for \(\textsf {Client}_2\) is \(~~ \emptyset ; \emptyset ; s_1: !\langle U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\cdot s_2: !\langle U\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\vdash \textsf {Client}_2 \triangleright \diamond \).

5 Characteristic bisimulation

We develop a theory for observational equivalence over session typed \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes that follows the principles laid in our previous works [18, 19]. We introduce higher-order bisimulation (Definition 17) and characteristic bisimulation (Definition 18), denoted \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\), respectively. We prove that they coincide with (reduction-closed) barbed congruence (denoted \(\cong \), cf. Definition 11), the form of contextual equivalence used in concurrency. This characterisation result is given in Theorem 2.

We briefly summarise our strategy for obtaining Theorem 2. We begin by defining an (early) labelled transition system (LTS) on untyped processes (Sect. 5.1). Then, using the environmental transition semantics (Sect. 5.2), we define a typed LTS that formalises how a typed process interacts with a typed observer. Later, we define reduction-closed, barbed congruence and context bisimilarity, respectively (Sects. 5.3 and 5.4). Subsequently, we define the refined LTS based on characteristic values (Sect. 5.5). Building upon this LTS, we define higher-order and characteristic bisimilarities (Sect. 5.6). Then, we develop an auxiliary proof technique based on deterministic transitions (Sect. 5.7). Our main result, the characterisation of barbed congruence in terms of \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\), is stated in Sect. 5.8. Finally, we revisit our two implementations for the Hotel Booking Scenario (Sect. 3.3), using Theorem 2 to show that they are behaviourally equivalent (Sect. 5.9).

5.1 Labelled transition system for processes

We define the interaction of processes with their environment using action labels \(\ell \):

Label \(\tau \) defines internal actions. Action \((\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V \rangle \) denotes the sending of value V over channel n with a possible empty set of restricted names \(\widetilde{m}\) (we may write \(n !\langle V \rangle \) when \(\widetilde{m}\) is empty). Dually, the action for value reception is \(n ?\langle V \rangle \). Actions for select and branch on a label l are denoted \(n \oplus l\) and \( n \, \& \, l\), respectively. We write \(\texttt {fn}(\ell )\) and \(\texttt {bn}(\ell )\) to denote the sets of free/bound names in \(\ell \), respectively. Given \(\ell \ne \tau \), we say \(\ell \) is a visible action; we write \(\texttt {subj}(\ell )\) to denote its subject. This way, we have: \( \texttt {subj}((\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V \rangle ) = \texttt {subj}(n ?\langle V \rangle ) = \texttt {subj}(n \oplus l) = \texttt {subj}(n \, \& \, l) = n\).

Dual actions occur on subjects that are dual between them and carry the same object; thus, output is dual to input and selection is dual to branching.

Definition 3

(Dual actions) We define duality on actions as the least symmetric relation \(\asymp \) on action labels that satisfies:

The (early) labelled transition system (LTS) fpr untyped processes is given in Fig. 4. We write \(P_1 \xrightarrow {\ell } P_2\) with the usual meaning. The rules are standard [18, 19]; we comment on some of them. A process with an output prefix can interact with the environment with an output action that carries a value V (Rule \({\langle \textsc {Snd} \rangle }\)). Dually, in Rule \({\langle \textsc {Rv} \rangle }\) a receiver process can observe an input of an arbitrary value V. Select and branch processes observe the select and branch actions in Rules \({\langle \textsc {Sel} \rangle }\) and \({\langle \textsc {Bra} \rangle }\), respectively. Rule \({\langle \textsc {Res} \rangle }\) enables an observable action from a process with an outermost restriction, provided that the restricted name does not occur free in the action. If a restricted name occurs free in the carried value of an output action, the process performs scope opening (Rule \({\langle \textsc {New} \rangle }\)). Rule \({\langle \textsc {Rec} \rangle }\) handles recursion unfolding. Rule \({\langle \textsc {Tau} \rangle }\) states that two parallel processes which perform dual actions can synchronise by an internal transition. Rules

and \({\langle \textsc {Alpha} \rangle }\) define standard treatments for actions under parallel composition and \(\alpha \)-renaming.

5.2 Environmental labelled transition system

Our typed LTS is obtained by coupling the untyped LTS given before with a labelled transition relation on typing environments, given in Fig. 5. Building upon the reduction relation for session environments in Definition 2, such a relation is defined on triples of environments by extending the LTSs in [18, 19]; it is denoted

Recall that \(\varGamma \) admits weakening. Using this principle (not valid for \(\varLambda \) and \(\varDelta \)), we have  whenever

whenever  .

.

Input actions are defined by Rules \({[{\textsc {SRv}]}}\) and \({[{\textsc {ShRv}]}}\). In Rule \({[{\textsc {SRv}]}}\) the type of value V and the type of the object associated to the session type on s should coincide. The resulting type tuple must contain the environments associated to V. The dual endpoint \(\overline{s}\) cannot be present in the session environment: if it were present the only possible communication would be the interaction between the two endpoints (cf. Rule \({[{\textsc {Tau}]}}\)). Following similar principles, Rule \({[{\textsc {ShRv}]}}\) defines input actions for shared names.

Output actions are defined by Rules \({[{\textsc {SSnd}]}}\) and \({[{\textsc {ShSnd}]}}\). Rule \({[{\textsc {SSnd}]}}\) states the conditions for observing action \((\nu \, \widetilde{m}) s !\langle V \rangle \) on a type tuple \((\varGamma , \varLambda , \varDelta \cdot s : S)\). The session environment \(\varDelta \,\cdot \, s : S\) should include the session environment of the sent value V (denoted \(\varDelta '\) in the rule), excluding the session environments of names \(m_j\) in \(\widetilde{m}\) which restrict the scope of value V (denoted \(\varDelta _j\) in the rule). Analogously, the linear variable environment \(\varLambda '\) of V should be included in \(\varLambda \). The rule defines the scope extrusion of session names in \(\widetilde{m}\); consequently, environments associated to their dual endpoints (denoted \(\varDelta '_j\) in the rule) appear in the resulting session environment. Similarly for shared names in \(\widetilde{m}\) that are extruded. All free values used for typing V (denoted \(\varLambda '\) and \(\varDelta '\) in the rule) are subtracted from the resulting type tuple. The prefix of session s is consumed by the action. Rule \({[{\textsc {ShSnd}]}}\) follows similar ideas for output actions on shared names: the name must be typed with \(\langle U \rangle \); conditions on value V are identical to those on Rule \({[{\textsc {SSnd}]}}\).

Other actions Rules \({[{\textsc {Sel}]}}\) and \({[{\textsc {Bra}]}}\) describe actions for select and branch. Rule \({[{\textsc {Tau}]}}\) defines internal transitions: it reduces the session environment (cf. Definition 2) or keeps it unchanged.

We illustrate Rule \({[{\textsc {SSnd}]}}\) by means of an example:

Example 2

Consider environment tuple \( (\varGamma ;\, \emptyset ;\, s: !\langle (!\langle S \rangle ; \texttt {end})\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\cdot s': S) \) and typed value \(V= \lambda x.\,x !\langle s' \rangle . m ?(z) . \mathbf {0}\) with

Then, by Rule \({[{\textsc {SSnd}]}}\), we can derive:

Observe how the protocol along s is partially consumed; also, the resulting session environment is extended with \(\overline{m}\), the dual endpoint of the extruded name m.

Notation 4

Given a value V of type U, we sometimes annotate the output action \((\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V \rangle \) with the type of V as \((\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V : U \rangle \).

The typed LTS combines the LTSs in Figs. 4 and 5.

Definition 5

(Typed transition system) A typed transition relation is a typed relation \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \xrightarrow {\ell } \varDelta _2 \vdash P_2\) where:

-

1.

\(P_1 \xrightarrow {\ell } P_2\) and

-

2.

\((\varGamma , \emptyset , \varDelta _1) \xrightarrow {\ell } (\varGamma , \emptyset , \varDelta _2)\) with \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta _i \vdash P_i \triangleright \diamond \) (\(i=1,2\)).

We write \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{}\) for the reflexive and transitive closure of \(\xrightarrow {}\), \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{\ell }\) for the transitions \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{}\xrightarrow {\ell }\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{}\), and \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{\hat{\ell }}\) for \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{\ell }\) if \(\ell \not = \tau \) otherwise \(\mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{}\).

A typed transition relation requires type judgements with an empty \(\varLambda \), i.e., an empty environment for linear higher-order types. Notice that for open process terms (i.e., with free variables), we can always apply Rule \( {[{{EProm}]}}\) (cf. Fig. 3) and obtain an empty \(\varLambda \). As it will be clear below (cf. Definition 7), we will be working with closed process terms, i.e., processes without free variables.

5.3 Reduction-closed, barbed congruence (\(\cong \))

We now define typed relations and contextual equivalence (i.e., barbed congruence). To define typed relations, we first define confluence over session environments \(\varDelta \). Recall that \(\varDelta \) captures session communication, which is deterministic. The notion of confluence allows us to abstract away from alternative computation paths that may arise due to non-interfering reductions of session names.

Definition 6

(Session environment confluence) Two session environments \(\varDelta _1\) and \(\varDelta _2\) are confluent, denoted \(\varDelta _1 \rightleftharpoons \varDelta _2\), if there exists a \(\varDelta \) such that: i) \(\varDelta _1 \longrightarrow ^*\varDelta \) and ii) \(\varDelta _2 \longrightarrow ^*\varDelta \) (here we write \(\longrightarrow ^*\) for the multi-step reduction in Definition 2).

We illustrate confluence by means of an example:

Example 3

(Session environment confluence) Consider the (balanced) session environments:

Following Definition 2, we have that \(\varDelta _1 \longrightarrow \{s_1: T_1 \cdot s_2: \texttt {end}\cdot \overline{s_2}: \texttt {end}\}\) and \(\varDelta _2 \longrightarrow \longrightarrow \{s_1: T_1 \cdot s_2: \texttt {end}\cdot \overline{s_2}: \texttt {end}\}\). Therefore, \(\varDelta _1\) and \(\varDelta _2\) are confluent. \(\square \)

Typed relations relate only closed processes whose session environments are balanced and confluent:

Definition 7

(Typed relation) We say that a binary relation over typing judgements

is a typed relation whenever:

-

1.

\(P_1\) and \(P_2\) are closed;

-

2.

\(\varDelta _1\) and \(\varDelta _2\) are balanced (cf. Definition 2); and

-

3.

\(\varDelta _1 \rightleftharpoons \varDelta _2\) (cf. Definition 6).

Notation 8

(Typed relations) We write

to denote the typed relation \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \triangleright \diamond \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta _2 \vdash P_2 \triangleright \diamond \).

Next we define barbs [24] with respect to types.

Definition 9

(Barbs) Let P be a closed process. We write

-

1.

-

(a)

\(P \downarrow _{n}\) if \(P \equiv (\nu \, \tilde{m})(n !\langle V \rangle . P_2 \;|\;P_3)\) or \(P \equiv (\nu \, \tilde{m})(n \triangleleft l . P_2 \;|\;P_3)\), with \(n \notin \tilde{m}\).

-

(b)

We write \(P \Downarrow _{n}\) if \(P \longrightarrow ^* \downarrow _{n}\).

-

(a)

-

2.

Similarly, we write

-

(a)

\(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \downarrow _{n}\) if \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \) with \(P \downarrow _{n}\) and \(\overline{n} \notin \varDelta \).

-

(b)

We write \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \Downarrow _{n}\) if \(P \longrightarrow ^* P'\) and \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta ' \vdash P' \downarrow _{n}\).

-

(a)

A barb \(\downarrow _{n}\) is an observable on an output (resp. select) prefix with subject n; a weak barb \(\Downarrow _{n}\) is a barb after zero or more reduction steps. Typed barbs \(\downarrow _{n}\) (resp. \(\Downarrow _{n}\)) are observed on typed processes \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \). When n is a session name we require that its dual endpoint \(\overline{n}\) is not present in the session environment \(\varDelta \).

Notice that observing output barbs is enough to (indirectly) observe input actions. For instance, the process \(P = n ?(x) . P'\) has an input barb on n; by composing P with \(n !\langle m \rangle . succ !\langle \rangle . \mathbf {0}\) (with a fresh name \(succ\)) then one obtains a (weak) observation uniquely associated to the input along n in P.

To define a congruence relation, we introduce the family \(\mathbb {C}\) of contexts:

Definition 10

(Context) Context \(\mathbb {C}\) is defined over the syntax:

Notation \(\mathbb {C}[P]\) denotes the result of substituting the hole \(-\) in \(\mathbb {C}\) with process P.

The first behavioural relation that we define is reduction-closed, barbed congruence [10].

Definition 11

(Reduction-closed, barbed congruence) Typed relation

is a reduction-closed, barbed congruence whenever:

-

(1)

-

(a)

If \(P \longrightarrow P'\) then there exist \(\varDelta _1', Q', \varDelta _2'\) such that \(Q \longrightarrow ^* Q'\) and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P' \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q'\);

-

(b)

and the symmetric case;

-

(a)

-

(2)

-

(a)

If \(\varGamma ;\varDelta _1 \vdash P \downarrow _{n}\) then \(\varGamma ;\varDelta _2 \vdash Q \Downarrow _{n}\);

-

(b)

and the symmetric case;

-

(a)

-

(3)

For all \(\mathbb {C}\), there exist \(\varDelta _1'',\varDelta _2''\) such that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1'' \vdash \mathbb {C}[P] \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2'' \vdash \mathbb {C}[Q]\).

The largest such relation is denoted with \(\cong \).

5.4 Context bisimilarity (\(\approx \))

Following Sangiorgi [31], we now define the standard (weak) context bisimilarity.

Definition 12

(Context bisimilarity) A typed relation \(\mathfrak {R}\) is a context bisimulation if for all \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1\),

-

(1)

Whenever \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \xrightarrow {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1}) n !\langle V_1 \rangle } \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2\), there exist \(Q_2\), \(V_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1 \mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2}) n !\langle V_2 \rangle } \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\) and for all R with \(\texttt {fv}(R)=\{x\}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta _1'' \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;RV_1/x) \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2'' \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;RV_2/x); \end{aligned}$$ -

(2)

For all \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \xrightarrow {\ell } \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2\) such that \(\ell \) is not an output, there exist \(Q_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1 \mathop {\Longrightarrow }\limits ^{\hat{\ell }} \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\) and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\); and

-

(3)

The symmetric cases of 1 and 2.

The largest such bisimulation is called context bisimilarity and is denoted by \(\approx \).

As suggested in Sect. 2, in the general case, context bisimilarity is an overly demanding relation on processes. Below we introduce higher-order bisimulation and characteristic bisimulation, which are meant to offer a tractable proof technique over session typed processes with first- and higher-order communication.

5.5 Characteristic values and the refined LTS

We formalise the ideas given in Sect. 2, concerning characteristic processes/values and the refined LTS. We first define characteristic processes/values:

Definition 13

(Characteristic process and values) Let u and U be a name and a type, respectively. The characteristic process of U (along u), denoted \([\!\!(U)\!\!]^{u}\), and the characteristic value of U, denoted \([\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}}\), are defined in Fig. 6.

We can verify that characteristic processes/values do inhabit their associated type.

Proposition 1

(Characteristic processes/values inhabit their types)

-

1.

Let U be a channel type. Then, for some \(\varGamma , \varDelta \), we have \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash [\!\!(U)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}} \triangleright U\).

-

2.

Let S be a session type. Then, for some \(\varGamma , \varDelta \), we have \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \cdot s: S \vdash [\!\!(S)\!\!]^{s} \triangleright \diamond \).

-

3.

Let U be a channel type. Then, for some \(\varGamma , \varDelta \), we have \(\varGamma \cdot a: U; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash [\!\!(U)\!\!]^{a} \triangleright \diamond \).

Proof

(Sketch) The proof is done by induction on the syntax of types. See Proposition 4 in the Appendix for details. \(\square \)

We give an example of a characteristic process inhabiting a recursive type.

Example 4

(Characteristic process for a recursive session type) Consider the type \(S = \mu \textsf {t}.!\langle U_1 \rangle ; ?(U_2) ; \textsf {t}\). By Definition 13, we have that \([\!\!(S)\!\!]^{s} = [\!\!(!\langle U_1 \rangle ; ?(U_2) ; \texttt {end})\!\!]^{s} = s !\langle [\!\!(U_1)\!\!]_{\textsf {c}} \rangle . t !\langle s \rangle . \mathbf {0}\). For this process, we can infer the following type derivations:

and

The following example motivates the refined LTS explained in Sect. 2. We rely on the following definition.

Definition 14

(Trigger value) Given a fresh name t, the trigger value on t is defined as the abstraction \(\lambda {x}.\,t ?(y) . (y\, {{x}})\).

Example 5

(The need for the refined typed LTS) We illustrate the complementary rôle that characteristic values (cf. Fig. 6) and the trigger value (Definition 14) play in defining sound bisimilarities.

We first notice that observing characteristic values as inputs is not enough to define a sound bisimulation. Consider processes

such that

with \(\varDelta = s_1{:}\texttt {end}\cdot s_2{:}\texttt {end}\). If \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) input along s a characteristic value of the form \([\!\!((\texttt {end})\!\! \rightarrow \! \diamond )\!\!]_{\textsf {c}} = \lambda z.\,\mathbf {0}\) (cf. Fig. 6), then both of them would evolve into:

therefore becoming context bisimilar. However, processes \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) in (3) are clearly not context bisimilar: many input actions may be used to distinguish them. For example, if \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) input \(\lambda x.\,(\nu \, s')(a !\langle s' \rangle . \mathbf {0})\) with \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \emptyset \vdash a \triangleright \langle \texttt {end} \rangle \), then their derivatives are not bisimilar:

Observing only the characteristic value results in an under-discriminating bisimulation. However, if a trigger value \(\lambda {x}.\,t ?(y) . (y\, {{x}})\) (Definition 14) is received along s, we can distinguish \(P_1\) and \(P_2\) in (3):

In the light of this example, one natural question is whether the trigger value suffices to distinguish two processes (hence no need of characteristic values). This is not the case: the trigger value alone also results in an under-discriminating bisimulation relation. In fact, the trigger value can be observed on any input prefix of any type. For example, consider processes:

If processes in (4) and (5) input the trigger value, we obtain:

thus we can easily derive a bisimulation relation if we assume a definition of bisimulation that allows only trigger value input. But if processes in (4)/(5) input the characteristic value \(\lambda z.\,z ?(x) . ( t !\langle z \rangle . \mathbf {0}\;|\;x\, {m})\) (where m is a fresh name) then, under appropriate \(\varGamma \) and \(\varDelta \), they would become:

which are not bisimilar if \(R_1 m/x \not \approx R_2 m/x\).

These examples illustrate the need for both trigger and characteristic values as an input observation in the refined transition relation. This will be the content of Definition 15 below. \(\square \)

As explained in Sect. 2, we define the refined typed LTS by considering a transition rule for input in which admitted values are trigger or characteristic values or names:

Definition 15

(Refined typed labelled transition system) The refined typed labelled transition relation on typing environments

is defined on top of the rules in Fig. 5 using the following rules:

Then, the refined typed labelled transition system

is given as in Definition 5, replacing the requirement \((\varGamma , \emptyset , \varDelta _1) \xrightarrow {\ell } (\varGamma , \emptyset , \varDelta _2)\) with  , as just defined. Following Definition 5, we write

, as just defined. Following Definition 5, we write  for the reflexive and transitive closure of

for the reflexive and transitive closure of  ,

,  for the transitions

for the transitions  , and

, and  for

for  if \(\ell \not = \tau \) otherwise

if \(\ell \not = \tau \) otherwise  .

.

Notice that the (refined) transition  implies the (ordinary) transition \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \xrightarrow {\,\ell \,} \varDelta _2 \vdash P_2\).

implies the (ordinary) transition \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \xrightarrow {\,\ell \,} \varDelta _2 \vdash P_2\).

Notation 16

We sometimes write  when the type of V is U.

when the type of V is U.

5.6 Higher-order bisimilarity (\(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\)) and characteristic bisimilarity (\(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\))

Having introduced a refined LTS on \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes, we now define higher-order bisimilarity and characteristic bisimilarity, two tractable bisimilarity relations. As explained in Sect. 2, the two bisimulations use two different trigger processes [cf. (2)]:

The process in (6) is called higher-order trigger process, while process in (7) is called characteristic trigger process. Notice that while in (6) there is a higher-order input on t, in (7) the variable x does not play any rôle.

We use higher-order trigger processes to define higher-order bisimilarity:

Definition 17

(Higher-order bisimilarity) A typed relation \(\mathfrak {R}\) is a higher-order bisimulation if for all \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1\)

-

(1)

Whenever

, there exist \(Q_2\), \(V_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that

, there exist \(Q_2\), \(V_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that  and, for a fresh t, $$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{lrlll} \varGamma ; \varDelta ''_1 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_1)} \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta ''_2 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_2)} \end{array} \end{aligned}$$

and, for a fresh t, $$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{lrlll} \varGamma ; \varDelta ''_1 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_1)} \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta ''_2 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_2)} \end{array} \end{aligned}$$ -

(2)

For all

such that \(\ell \) is not an output, there exist \(Q_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that

such that \(\ell \) is not an output, there exist \(Q_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that  and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\); and

and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\); and -

(3)

The symmetric cases of 1 and 2.

The largest such bisimulation is called higher-order bisimilarity, denoted by \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\).

We exploit characteristic trigger processes to define characteristic bisimilarity:

Definition 18

(Characteristic bisimilarity) A typed relation \(\mathfrak {R}\) is a characteristic bisimulation if for all \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1\),

-

(1)

Whenever

then there exist \(Q_2\), \(V_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that

then there exist \(Q_2\), \(V_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that  and, for a fresh t, $$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta ''_1 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V_1{\,:\,}U_1)} \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta ''_2 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V_2{\,:\,}U_2)} \end{aligned}$$

and, for a fresh t, $$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta ''_1 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V_1{\,:\,}U_1)} \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta ''_2 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V_2{\,:\,}U_2)} \end{aligned}$$ -

(2)

For all

such that \(\ell \) is not an output, there exist \(Q_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that

such that \(\ell \) is not an output, there exist \(Q_2\), \(\varDelta '_2\) such that  and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\); and

and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\); and -

(3)

The symmetric cases of 1 and 2.

The largest such bisimulation is called characteristic bisimilarity, denoted by \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\).

Observe how we have used Notation 16 to explicitly refer to the type of the emitted value in output actions.

Remark 1

(Differences between \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\)) Although \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) are conceptually similar, they differ in the kind of trigger process considered. Because of the application in \(t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V\) (cf. (6)), \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) cannot be used to reason about first-order session processes (i.e., processes without higher-order features). In contrast, \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) is more general: it can uniformly input characteristic, first- or higher-order values.

5.7 Deterministic transitions and up-to techniques

As hinted at earlier, internal transitions associated to session interactions or \(\beta \)-reductions are deterministic. To define an auxiliary proof technique that exploits determinacy we require some auxiliary definitions.

Definition 19

(Deterministic transitions) Suppose \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \) with balanced \(\varDelta \). Transition  is called:

is called:

-

session-transition whenever transition \(P \xrightarrow {\tau } P'\) is derived using Rule \({\langle \textsc {Tau} \rangle }\) (where \(\texttt {subj}(\ell _1)\) and \(\texttt {subj}(\ell _2)\) in the premise are dual endpoints), possibly followed by uses of Rules \({\langle \textsc {Alpha} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Res} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Rec} \rangle }\), or

(cf. Fig. 4).

-

a \(\beta \)-transition whenever transition

is derived using Rule \({\langle \textsc {App} \rangle }\), possibly followed by uses of Rules \({\langle \textsc {Alpha} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Res} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Rec} \rangle }\), or

is derived using Rule \({\langle \textsc {App} \rangle }\), possibly followed by uses of Rules \({\langle \textsc {Alpha} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Res} \rangle }\), \({\langle \textsc {Rec} \rangle }\), or

(cf. Fig. 4).

Notation 20

We use the following notations:

-

denotes a session-transition.

denotes a session-transition. -

denotes a \(\beta \)-transition.

denotes a \(\beta \)-transition. -

denotes either a session-transition or a \(\beta \)-transition.

denotes either a session-transition or a \(\beta \)-transition. -

We write

to denote a (possibly empty) sequence of deterministic steps

to denote a (possibly empty) sequence of deterministic steps  .

.

Deterministic transitions imply the \(\tau \)-inertness property [7], which ensures behavioural invariance on deterministic transitions:

Proposition 2

(\(\tau \)-inertness) Suppose \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \) with balanced \(\varDelta \). Then

-

1.

implies \(\varGamma ; \varDelta \vdash P \approx ^\mathtt{H} \varDelta ' \vdash P'\).

implies \(\varGamma ; \varDelta \vdash P \approx ^\mathtt{H} \varDelta ' \vdash P'\). -

2.

implies \(\varGamma ; \varDelta \vdash P \approx ^\mathtt{H} \varDelta ' \vdash P'\).

implies \(\varGamma ; \varDelta \vdash P \approx ^\mathtt{H} \varDelta ' \vdash P'\).

Proof

(Sketch) The proof of Part 1 requires to show that relation (we omit type information)

is a higher-order bisimulation. The proof for Part 2 is direct from Part 1. See “Deterministic transitions” section of Appendix 2 for the details. \(\square \)

Using the above properties, we can state the following up-to technique.

Lemma 1

(Up-to deterministic transition) Let \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P_1 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash Q_1\) such that if whenever:

-

1.

\(\forall (\nu \, \widetilde{m_1}) n !\langle V_1 \rangle \) such that

implies that \(\exists Q_2, V_2\) such that

implies that \(\exists Q_2, V_2\) such that  and

and  and for a fresh name t and \(\varDelta _1'', \varDelta _2''\): $$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta _1'' \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_1) \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2'' \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_2)} \end{aligned}$$

and for a fresh name t and \(\varDelta _1'', \varDelta _2''\): $$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta _1'' \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_1) \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2'' \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_2)} \end{aligned}$$ -

2.

\(\forall \ell \not = (\nu \, \widetilde{m}) n !\langle V \rangle \) such that

implies that \(\exists Q_2\) such that

implies that \(\exists Q_2\) such that  and

and  and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\).

and \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P_2 \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q_2\). -

3.

The symmetric cases of 1 and 2.

Then \(\mathfrak {R}\ \subseteq \ \approx ^\mathtt{H}\).

Proof

(Sketch) The proof proceeds by considering the relation

We may verify that  is a higher-order bisimulation by using Proposition 2. \(\square \)

is a higher-order bisimulation by using Proposition 2. \(\square \)

5.8 Characterisation of higher-order and characteristic bisimilarities

This section proves the main result; it allows us to use \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) as tractable reasoning techniques for \(\textsf {HO}\pi \) processes.

Lemma 2

\(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\ =\ \approx ^\mathtt{H}\).

Proof

(Sketch) The main difference between \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) is the trigger process (higher-order triggers \(t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V\) in \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and characteristic triggers \(t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V{\,:\,}U\) in \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\)). Thus, the most interesting case in the proof is when we observe an output from a process. When showing that \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\ \subseteq \ \approx ^\mathtt{H}\), the key after the output is to show that

given that

Similarly, in the proof of \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\ \subseteq \ \approx ^\mathtt{C}\), the key step is showing that

given that

The proof for the above equalities is coinductive, exploiting the freshness of the trigger name in each case; see Lemma 13 in the Appendix. While the proof of the first equality (i.e., higher-order triggers imply characteristic triggers) follows expected lines, the proof of the second equality (i.e., characteristic triggers imply higher-order triggers) is a bit more involved. Indeed, while higher-order trigger processes can input trigger values, characteristic triggers cannot. However, we prove that this does not represent a difference in behaviour; see case 2(c) in Lemma 13. To this end, we exploit an alternative trigger process, denoted \(t \leftharpoonup _\texttt {A} V\), simpler than the higher-order trigger \(t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V\) in (6):

In the proofs for these coincidence results, we exploit some auxiliary results for trigger processes, including a two-way connection between \(t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V\) and \(t \leftharpoonup _\texttt {A} V\) (cf. Lemma 12 (3) in the Appendix). We thus infer that characteristic trigger processes \(t \Leftarrow _{\texttt {C}} V{\,:\,}U\) and higher-order trigger processes \(t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V\) exhibit a similar behaviour.

In turn, using the above results we can show that typed relations induced by \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) coincide. The full proof is in “Proof of Theorem 2” section in Appendix 2, Lemma 14. \(\square \)

The next lemma is crucial for the characterisation of higher-order and characteristic bisimilarities. It states that if two processes are equivalent under the trigger value then they are equivalent under any higher-order substitution.

Lemma 3

(Process substitution) Let P and Q be two processes and some fresh t. If

then for all R such that \(\texttt {fv}(R) = \{x\}\), we have

The full proof of Lemma 3 can be found in “Proof of Theorem 2” section in Appendix 2, Lemma 17; it is obtained by (i) constructing a typed relation on the substitution properties stated by the lemma and (ii) proving that it is a higher-order bisimulation, using the auxiliary result given next. In the following, given a finite index set \(I = \{1, \ldots , n\}\), we shall write \(\prod _{i \in I} P_i\) to stand for \(P_1 \;|\;P_2 \;|\;\cdots \;|\;P_n\).

Lemma 4

(Trigger substitution) Let P and Q be processes. Also, let t be a fresh name. If

then for all \(\lambda \widetilde{x}.\,R\), there exist \(\varDelta _1', \varDelta _2'\) such that

Proof

(Sketch) The proof follows the definition of the characteristic process; see Lemma 16, in the Appendix for details. Let us consider the particular case in which I is a singleton; we then construct a typed relation \(\mathfrak {R}\):

The typed relation \(\mathfrak {R}\) can be shown to be a higher-order bisimulation by taking advantage of the shape of the characteristic process; each time that a characteristic process does a transition, an output \(t !\langle n \rangle . \mathbf {0}\) (on a fresh name t) is observed, where n is either a shared or a session name. To better illustrate this, let us sketch the demanding case of the proof that \(\mathfrak {R}\) is a higher-order bisimulation. Assume that

for some \(\varDelta ''_1\). Then, from the definition of \(\mathfrak {R}\), we have:

for some \(\varDelta _3\). Characteristic processes have the following property, for any \(U \ne \texttt {end}\):

By the last property we can always observe, for some \(\varDelta ''_3\) (note that below \(\ell _1\) may be an action \(\tau \), thus denoting the interaction of P and \([\!\!(U)\!\!]^{n_1}\)):

which implies, from the requirements of higher-order bisimulation, that there exist \((\nu \, \widetilde{m_2}'')(Q' \;|\;[\!\!(U)\!\!]^{x} n_2/x )\) and \(\varDelta _4\) such that

By the shape of the characteristic process we can always observe for \(\ell _2, \texttt {subj}(\ell _2) = \texttt {subj}(\ell _1)\) if \(\ell _1\) is output, and \(\ell _2 = \ell _1\) otherwise, that:

for some \(\varDelta '_4\) and

for some \(\varDelta ''_4\). From (8) we get

for some \(\varDelta ''_2\) and from (9) we get

which implies from the definition of \(\mathfrak {R}\) that for \(R'\) we get

as required. \(\square \)

We now show that higher-order bisimilarity is sound with respect to context bisimilarity. To show soundness we use the crucial result of Lemma 3:

Lemma 5

\(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\ \subseteq \ \approx \).

Proof

(Sketch) The proof relies on Lemma 3 to establish that:

-

1.

Whenever two processes are higher-order bisimilar under the input of a characteristic value and a trigger value then they are higher-order bisimilar under the input of any value \(\lambda x.\,R\), which is the requirement for \(\approx \) (cf. Definition 12).

-

2.

The input requirement is then further used to prove that the output clause requirement for \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) (cf. Definition 17):

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{lrlll} \varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_1)} \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash {(\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;t \hookleftarrow _{\texttt {H}} V_2)} \end{array} \end{aligned}$$implies the output clause requirement for \(\approx \), that is, for all R with \(\texttt {fv}(R)=\{x\}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_1})(P_2 \;|\;RV_1/x) \ \mathfrak {R}\ \varDelta _2 \vdash (\nu \, \widetilde{m_2})(Q_2 \;|\;RV_2/x). \end{aligned}$$

The full proof is found in “Proof of Theorem 2” section in Appendix 2, Lemma 18. \(\square \)

Context bisimilarity is included in barbed congruence:

Lemma 6

\(\approx \ \subseteq \ \cong \).

Proof

(Sketch) We show that \(\approx \) satisfies the defining properties of \(\cong \). It is easy to show that \(\approx \) is reduction-closed and barb preserving (cf. Definition 6 and Definition 9). The most challenging part is to show that \(\approx \) is a congruence, in particular a congruence with respect to parallel composition. To this end, we construct the following relation:

We show that \({\mathcal {S}}\) is a context bisimulation by a case analysis on the transitions of the pairs in \({\mathcal {S}}\). The full proof is found in “Proof of Theorem 2” section in Appendix 2, Lemma 19. \(\square \)

The last ingredient required for our main result is the following inclusion.

Lemma 7

\(\cong \ \subseteq \ \approx ^\mathtt{H}\).

Proof

(Sketch) The proof exploits the definability technique developed in [8, § 6.7] and refined for session types in [18, 19]. Intuitively, this technique exploits small test processes that reveal the presence of a visible action by reducing with a given pair of processes and exhibiting a barb on a fresh name.

Intuitively, for each visible action \(\ell \), we use a fresh name \(succ\) to we define a (typed) test process \(\varGamma ; \emptyset ; \varDelta _2 \vdash T\langle \ell , succ \rangle \triangleright \diamond \) with the following property:

See Definition 25 for the formal definition. The test processes can therefore be used to check the typed labelled transition interactions of two processes that are related by reduction-closed, barbed congruence. Indeed, we have that

implies from congruence of \(\cong \), that if there exist \(\varDelta _3, \varDelta _4\) such that:

then it implies from reduction-closeness of \(\cong \) and the definition of \(T\langle \ell , succ \rangle \):

which in turn means that whenever \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1 \vdash P \triangleright \diamond \) can perform an action  then we can derive that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _2 \vdash Q \triangleright \diamond \) can also perform action

then we can derive that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _2 \vdash Q \triangleright \diamond \) can also perform action  because of the result in (10). By applying Lemma 21 on (10) we can deduce that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P'\ \cong \ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q'\). This concludes the requirements of \(\approx \):

because of the result in (10). By applying Lemma 21 on (10) we can deduce that \(\varGamma ; \varDelta _1' \vdash P'\ \cong \ \varDelta _2' \vdash Q'\). This concludes the requirements of \(\approx \):

The full details can be found in “Proof of Theorem 2” section in Appendix 2, Lemma 22. \(\square \)

We can finally state our main result:

Theorem 2

(Coincidence) \(\cong \), \(\approx \), \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\) and \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) coincide in \(\textsf {HO}\pi \).

Proof

The proof is a direct consequence from our previous results: Lemma 2 (which proves \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\ =\ \approx ^\mathtt{C}\)), Lemma 5 (which proves \(\approx ^\mathtt{H}\ \subseteq \ \approx \)), Lemma 6 (which proves \(\approx \ \subseteq \ \cong \)), and Lemma 7 (which proves \(\cong \ \subseteq \ \approx ^\mathtt{H}\)). Indeed, we may conclude

\(\square \)

Observable actions from \(\textsf {Client}_1\) (cf. Sect. 5.9)

5.9 Revisiting the hotel booking scenario (Sect. 3.3)

Now we revisit our running example to prove that \(\textsf {Client}_1\) and \(\textsf {Client}_2\) in Sect. 3.3 are behaviourally equivalent.

Proposition 3

Let \(S = !\langle \textsf {room} \rangle ; ?(\textsf {quote}) ; \oplus \{\textsf {accept}: !\langle \textsf {credit} \rangle ; \texttt {end}, \textsf {reject}: \texttt {end}\}\) and \(\varDelta = s_1: !\langle S\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\cdot s_2: !\langle S\!\! \multimap \! \diamond \rangle ; \texttt {end}\). Then \(\emptyset ; \varDelta \vdash \textsf {Client}_1 \approx ^\mathtt{C} \varDelta \vdash \textsf {Client}_2\), where \(\textsf {Client}_1\) and \(\textsf {Client}_2\) are as in Sect. 3.3.

Proof

We show a case where each typed process simulates the other, according to the definition of \(\approx ^\mathtt{C}\) (cf. Definition 18). In order to show the bisimulation game consider the definition of the characteristic process for type \(?(S\!\! \multimap \! \diamond ) ; \texttt {end}\). For fresh sessions s, k, we have

For convenience, we recall the definition of \(\textsf {Client}_1\):

where

Also, the definition of \(\textsf {Client}_2\) is as follows:

A detailed account of the observable behaviour of \(\textsf {Client}_1\) is given in Fig. 7, where we use the following shorthand notation:

Observable actions from \(\textsf {Client}_2\) (cf. Sect. 5.9)

Similarly, Fig. 8 illustrates the actions possible from \(\textsf {Client}_2\), which are the same as for \(\textsf {Client}_1\). \(\square \)

6 Related work

Since types can limit contexts (environments) where processes can interact, typed equivalences usually offer coarser semantics than untyped equivalences. Pierce and Sangiorgi [28] demonstrated that IO-subtyping can justify the optimal encoding of the \(\lambda \)-calculus by Milner—this was not possible in the untyped polyadic \(\pi \)-calculus [23]. After [28], several works on typed \(\pi \)-calculi have investigated correctness of encodings of known concurrent and sequential calculi in order to examine semantic effects of proposed typing systems.

A type discipline closely related to session types is a family of linear typing systems. Kobayashi, Pierce, and Turner [14] first proposed a linearly typed reduction-closed, barbed congruence and used it to reason about a tail-call optimisation of higher-order functions encoded as processes. Yoshida [35] used a bisimulation of graph-based types to prove the full abstraction of encodings of the polyadic synchronous \(\pi \)-calculus into the monadic synchronous \(\pi \)-calculus. Later, typed equivalences of a family of linear and affine calculi [2, 3, 36] were used to encode PCF [22, 29], the simply typed \(\lambda \)-calculus with sums and products, and System F [6] fully abstractly (a fully abstract encoding of the \(\lambda \)-calculi was an open problem in [23]). Yoshida et al. [37] proposed a new bisimilarity method associated with a linear type structure and strong normalisation; it presented applications to reason about secrecy in programming languages. A subsequent work [11] adapted these results to a practical direction, proposing new typing systems for secure higher-order and multi-threaded programming languages. In these works, typed properties, linearity and liveness, play a fundamental rôle in the analysis. In general, linear types are suitable to encode “sequentiality” in the sense of [1, 12].

Our work follows the behavioural semantics in [18, 19, 27] where a bisimulation is defined on an LTS that assumes a session typed observer. Our theory for higher-order sessions differentiates from the work in [19] and [18], which considers (first-order) binary and multiparty session types, respectively. Pérez et al [27] studied typed equivalences for a theory of binary sessions based on linear logic, without shared names.