Abstract

The Longqi vent field, situated on the Southwest Indian Ridge, is ecologically distinct among known hydrothermal vents fields. It hosts a combination of previously unknown species and those shared at species or genus level with other hydrothermal vents on the Central Indian Ridge (CIR) and East Scotia Ridge (ESR). We investigate the size-based and trophodynamics of consumers at Longqi vent field and compared these with ESR and CIR vent fields using stable isotope analysis. Intra-specific variability in δ13C and δ15N values in relationship to shell length was observed in Gigantopelta aegis but absent in Chrysomallon squamiferum. A model-based clustering approach identified four trophic groupings at Longqi: species with the lowest δ13C values being supported by carbon fixed via the Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle, the highest δ13C values being supported by the reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle and intermediate values potentially supported by a mix of these primary production sources. These clusters were driven by potential differences in resource partitioning. There were also differences in the spread of stable isotope values at the vent field level when comparing Bayesian stable isotope ellipse areas among Longqi, CIR and ESR vent fields. This was driven by a combination of the range in δ13C value of macrofauna, and the negative δ15N values which were only observed at Longqi and CIR vent fields. Many of the shared species or genera showed inter-vent field differences in stable isotope values which may be related to site-specific differences in food sources, geochemistry or potential intra-field competition. This study provides important information on the trophic ecology of hydrothermal vent macrofauna found within an area of seabed that is licensed for seabed mining exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deep-sea hydrothermal vents are patchy, ephemeral habitats that occur along tectonically or volcanically active mid-ocean ridges, back-arc spreading centres and seamounts (Tunnicliffe et al. 2003; Staudigel et al. 2006). Microbial and macrofaunal biomass at hydrothermal vents are typically higher in comparison with the surrounding deep sea because of in situ primary production by chemotrophic bacteria, which forms the base of the food web. These bacteria can be free living microbes, epibionts or found as endosymbionts in some macrofaunal species (Childress and Fisher 1992; Karl 1995; Sievert and Vetriani 2012). Chemotrophic bacteria use the energy from reduced chemical species (e.g. H2S, HS−, CH4) present in vent fluid emitted from the seafloor to convert inorganic carbon sources (e.g. CO2) into simple organic compounds (McCollom and Shock 1997). Organic matter produced via chemosynthetic primary production is the dominant food source at active hydrothermal vents, which supports the specialist fauna found in those habitats (Sievert and Vetriani 2012).

The temperature and geochemical composition of hydrothermal vent fluid emitted from the seafloor are two important factors influencing the distribution of microbial and macrofaunal communities (Sarrazin et al. 1999, 2015; Dick 2019). The hydrothermal vent habitat has a high degree of spatial heterogeneity in environmental conditions, even though individual vent fields are relatively small-scale features on the seafloor (Butterfield et al. 1994; German and Von Damm 2003; Tivey 2007). Coupled with temporal variability in the degree of hydrothermal activity, this results in a dynamic ecosystem, governed by subsurface processes (German and Von Damm 2003; Kelley et al. 2005). The dominant bacterial primary producers, Epsilonproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria, occupy different temperature and geochemical regimes (Campbell et al. 2006; Hügler and Sievert 2011). These bacterial groups fix carbon using different enzymatic systems (Hügler and Sievert 2011). The reductive tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle is used by Epsilonproteobacteria, which dominate areas where temperature is > 20 °C, oxygen levels are low and microaerobic growth can occur using additional electron acceptors including NO3−(Hügler and Sievert 2011). In contrast, Gammaproteobacteria use the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle in areas where temperature is < 20 °C and oxygen is far more plentiful (Hügler and Sievert 2011; Yamamoto and Takai 2011).

Overlain on this microbial template are dense macrofaunal communities that utilize chemosynthetic primary production (Van Dover and Fry 1994; Colaço et al. 2002; Reid et al. 2013). The proximity to high-temperature fluids and tolerance of toxic vent effluent are important determinants of species distributions (Sarrazin et al. 1999; Henry et al. 2008; Podowski et al. 2010). Macrofauna exploit vent-derived primary production through endosymbiotic and epibiotic relationships, grazing on free-living microbes and particulate organic matter from hard surfaces, or through suspension feeding in the water column and indirectly through predation and scavenging (Colaço et al. 2002; Van Dover 2002; Reid et al. 2013). The result is specific faunal patterns of zonation around hydrothermal fluid sources that are potentially linked to trophic guilds and specific chemotrophic primary producers (Marsh et al. 2012). These patterns are often consistent within a biogeographical province depending on the successional stage of the hydrothermal vent (Marsh et al. 2012; Sarrazin et al. 2015).

Stable isotopes of carbon (13C/12C expressed as δ13C) and nitrogen (15N/14N expressed as δ15N) are routinely used to investigate species-specific and trophodynamics at hydrothermal vents (Fisher et al. 1994; Colaço et al. 2002; Van Dover 2002; Reid et al. 2013; Bell et al. 2017). Stable isotopes have certain advantages over other techniques for studying food webs, especially those where stomach content analysis may be prohibitive depending on the dietary sources. Stable isotopes measure the organic material that is assimilated from an organism’s diet post-digestion and provide temporally and spatially integrated information on energy flow within a system (Post 2002; Newsome et al. 2007). δ13C and δ15N are used to identify different characteristics of the food web. δ13C has lower trophic discrimination (0 to ~ 1‰) between food source and consumer than δ15N (~ 2‰ to ~ 4‰) making it suitable for distinguishing different carbon fixation pathways which are isotopically discrete (Post 2002; Caut et al. 2009). At hydrothermal vents, this allows for putative assessment of which carbon fixation pathways are potentially supporting macrofauna; the range of δ13C values of carbon fixed via the rTCA cycle is between ~ − 15‰ to ~ − 10‰, and those of the CBB cycle are ~ − 35‰ to ~ − 20‰ (Hügler and Sievert 2011; Reid et al. 2013; Portail et al. 2016). The wide range in δ13C values observed in organisms dependent on the CBB cycle is partly because there are different forms of the enzyme ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) used to catalyse the carboxylation or oxidation of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate during the first step of autotrophic CO2 fixation (Hügler and Sievert 2011). The stable isotopic fraction differs between form I and II RuBisCO with form I RuBisCO ranging between 22‰ and 30‰ (Guy et al. 1993; Scott 2003; Scott et al. 2004) while form II RuBisCO ranges between 18‰ and 23‰ (Guy et al. 1993; Robinson et al. 2003). The result is that hydrothermal vent fauna with δ13C values at the lower end of the range associated with the CBB cycle are potentially utilizing carbon fixed via the form I RuBisCo, while those with values closer to − 20‰ are utilizing carbon fixed via form II RuBisCO. δ15N is often used to estimate trophic position in food webs because of the greater trophic discrimination between predator and prey than is observed in δ13C (Peterson and Fry 1987; Post 2002).

The Longqi vent field is located on the Southwest Indian Ridge (SWIR) at 37° 47′ S and 49° 39′ E at a depth of approximately 2750 m (Tao et al. 2012; Copley et al. 2016). The SWIR is the longest section of very slow to ultra-slow seafloor spreading ridge in the global mid-ocean ridge system and is spreading at a rate of approximately 14–16 mm year−1(Dick et al. 2003). It contains massive sulphide deposits (Tao et al. 2014) as well as established sulphide structures including black-smoker chimneys (> 300 °C), diffuse flow areas (< 100 °C) and inactive chimneys (Copley et al. 2016; Ji et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2018). The Longqi vent field is found within an area of seabed that is licensed to the China Ocean Minerals Resources R & D Association by the International Seabed Authority for polymetallic metal exploration. The Longqi vent field contains several macrofaunal species not yet recorded at other vent fields (Copley et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2018). There are also major similarities in some macrofaunal species between the Longqi vent field and Central Indian Ridge (CIR) vent fields suggesting that it is part of an Indian Ocean vent biogeographical province (Copley et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2018). Furthermore, Longqi vent field appears to have also historical or current connections to the East Scotia Ridge (ESR) which shares a number of species or genera (Chen et al. 2015b; Herrera et al. 2015; Copley et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2018). Some of the species and genera shared with other vent fields are found in similar habitats and distance from high-temperature venting. These include the crustaceans Rimicaris kairei (Crustacea; Malacostrata), Mirocaris sp. (Crustacea; Malacostrata), and Kiwa sp. (Crustacea; Malacostrata), which were observed close to the high-temperature fluid sources; the scaly-foot gastropod Chrysomallon squamiferum (Mollusca; Gastropoda) and Bathymodiolus marisindicus (Mollusca; Bivalvia) which were found within lower-temperature diffuse flow areas; and Neolepas (Crustacea; Hexanauplia) which dominates at the periphery of the vent field (Marsh et al. 2012; Copley et al. 2016).

Here, we examine the trophodynamics at the Longqi vent field on the SWIR and compare it with hydrothermal vents on the ESR and CIR. The aims of this research are: (1) to investigate the size-based trophic ecological interactions in Gigantopelta aegis (Mollusca; Gastropoda) and C. squamiferum; (2) to investigate trophic interactions at Longqi vent field; and (3) to compare the trophic structure of the Longqi vent field with that of the ESR and CIR vent fields.

Methods

Sample collection

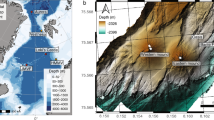

The Longqi vent field (Fig. 1) was sampled between 27 to 30th November 2011 using the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) ROV KIEL 6000 from onboard the RRS James Cook (Copley et al. 2016). Faunal specimens were collected from different locations in the vent field using the ROV’s suction sampler and scoops and placed into different containers. Once the samples were retrieved on the ship after the ROV dives, they were transferred to a shipboard 4 °C constant-temperature laboratory and sorted into morphospecies. Samples for stable isotope analysis were then frozen whole at − 80 °C.

Stable isotope preparation and analysis

In the laboratory, samples were part defrosted, dissected to remove specific tissues for analysis (Table 1), rinsed with distilled water and refrozen at − 80 °C. Neolepas marisindica (Crustacea; Hexanauplia) was analysed whole because of low sample mass. For C. squamiferum, the external proteinaceous dermal sclerites were removed from their foot. The shell length (mm) for C. squamiferum and G. aegis was measured along the central axis from the shell apex to the outer lip using vernier callipers. Tissue samples were freeze-dried and ground to a fine homogenous powder using a pestle and mortar. Samples were tested for carbonates by the drop-wise addition of 0.1 N HCl. None of the samples showed evidence of effervescence, which indicated that carbonates were not present and therefore no samples were acidified before analysis.

Approximately 1 mg of powder was weighed into a tin capsule for dual carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis using an elemental analyser coupled to a Europa Scientific 20–20 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (Iso-Analytical, Crewe, United Kingdom). The following samples were run for quality control: IA-R068 soy protein, δ13C = − 25.22‰ ± 0.05 standard deviation (SD), δ15N = 0.99‰ ± 0.04 SD, IA-R038 (L-alanine, δ13C = − 25.16‰ ± 0.03 SD, δ15N = − 0.55‰ ± 0.01 SD), IA-R069 (tuna protein, δ13C = − 18.91‰ ± 0.04 SD, δ15N = 11.64‰ ± 0.02 SD) and a mixture of IAEA-C7 (oxalic acid, δ13C = − 14.50‰ ± 0.05 SD) and IA-R046 (ammonium sulfate, δ15N = 21.76‰ ± 0.03 SD). IA-R068, IA-R038 and IA-R069 internal standards which are calibrated against and traceable to IAEA-CH-6 (sucrose, δ13C = − 10.43‰) and IAEA-N-1 (ammonium sulfate, δ15N = 0.40‰). IA-R046 is calibrated against and traceable to IAEA-N-1. IAEA-C7, IAEA-CH-6 and IAEA-N-1 are inter-laboratory comparison standards distributed by the International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna. Stable isotope ratios were expressed in the delta (δ) notation as parts per thousand/ per mil (‰). An external reference material of freeze-dried and ground fish muscle (Antimora rostrata) was also analysed (δ13C, n = 7, − 18.84‰ ± 0.11 SD; δ15N, n = 7, 13.22‰ ± 0.12 SD).

Data analysis

Generalized linear models (GLM) were used to assess the relationship between δ13C or δ15N and shell length for the oesophageal gland and foot in C. squamiferum and G. aegis. The model assumptions were examined by inspecting the plots of residuals versus fitted values and qqplots. The full model is reported. The δ13C and δ15N values of Longqi fauna were examined to see whether distinctive clusters were present. A model-based clustering approach was implemented using the package mclust (Scrucca et al. 2016). The foot was included in the model-based clustering analysis for the species Bathymodiolus marisindicus, C. squamiferum and G. aegis because these are muscular tissues. The gill tissue of B. marisindicus and the oesophageal glands of C. squamiferum and G. aegis, which host endosymbionts, were excluded from this analysis because these were not independent from the foot tissue, having been taken from the same individuals. The model-based clustering is based on a finite Gaussian mixture model and is fitted by an expectation–maximization algorithm. The optimal model containing the number of mixing components and the geometric features of the shape was assessed using Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The optimal model is chosen based on the highest BIC score. The optimal model was an EVI model where all clusters were equal (E), the shapes of the clusters varied (V) and the orientation was the identity (I) resulting in clusters parallel to the coordinate axes. Given the difference in BIC between the EVI model with 5 (BIC = − 446.87) and 4 (BIC = − 448.39) clusters was only 1.52 and the greater uncertainty in the classification of a number of individuals in the 5 cluster model (Supplementary Fig 1), the 4 cluster model was deemed more appropriate.

The variability in stable isotope values across the species sampled at Longqi vent field was compared with published data from the Kairei, E2 and E9 vent fields (Van Dover 2002; Reid et al. 2013; Copley et al. 2016). Sample size corrected standard ellipse area (SEAc), Bayesian standard ellipse area (SEAb), eccentricity (shape of the SEAc) and theta (the angle in radians between semi-major axis and the x-axis) were calculated using the SIBER package (Jackson et al. 2011). Eccentricity and theta are parameters used to calculate the standard ellipse area. They have been used to distinguish the SEAc in species-specific trophic studies where SEAc are similar size among species but the shape or inclination of the SEAc in xy-space differs (Reid et al. 2016). Here, we used them to examine differences in isotope variability among the four hydrothermal vent fields at the community level. To compare the community level SEAb, the model was run for 20 000 iterations, with a burn-in of 10,000 and then thinned by a factor of 10. The mode for each vent field is reported along with the 95% credible interval (CI). All data analysis was undertaken using R version 4.0.2 and data used in these analyses can be found in the Supplementary data spreadsheet.

Results

Endosymbiont-hosting size-based trophic relationships

There was no relationship between either δ13C or δ15N values of the oesophageal gland and foot with shell length (range 21–38 mm) in C. squamiferum (GLM: δ13C v shell length, t = 1.277, p = 0.2577; δ15N v shell length, t = 1.331, p = 0.241). The oesophageal gland had consistently lower stable isotope values compared with the foot (GLM: δ13C v tissue, t = − 3.210, p = 0.0237; δ15N v tissue, t = − 38.784, p < 0.001; Fig. 2a, b). This indicated that the tissue off-set was similar regardless of size (Fig. 2a, b). The GLM estimated that the oesophageal gland was 2.3‰ [± 0.7 standard error (SE)] and 2.6‰ (± 0.1 SE) lower than the foot for δ13C and δ15N, respectively.

The relationship between (a) δ13C or (b) δ15N and shell length (mm) in Chrysomallon squamiferum. Solid circles represent foot and the solid triangles represent the oesophageal gland. Grey shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. The relationship between δ13C and shell length: foot δ13C = − 24.44863 + (shell length × 0.07022); oesophageal gland δ13C = ( − 24.44863 − 2.22308) + (shell length × 0.07022) The relationship between δ15N and shell length: foot δ15N = 3.438596 + (shell length × 0.007024); oesophageal gland δ15N = (3.438596 − 2.642500) + (shell length × 0.007024). Foot and oesophageal gland tissues did not vary with shell length for δ13C and δ15N

In contrast, there was a positive relationship between the δ13C values in the oesophageal gland and foot with shell length (range 15–35 mm) in G. aegis (GLM: t = 3.141, p = 0.00458; Fig. 3a). The oesophageal gland had consistently lower δ13C compared with the foot (GLM: t = − 3.141, p < 0.0001). For δ15N, however, there was a negative relationship between the δ15N values in the oesophageal gland and foot with shell length (GLM: t = − 4.744, p < 0.001). The δ15N values in the oesophageal gland were lower than the foot (GLM: t = − 22.518, p < 0.001; Fig. 3b). The GLM estimated a difference between oesophageal gland and foot of 2.2‰ (± 0.2 SE) for δ13C, which was similar to that observed in C. squamiferum. The difference between oesophageal gland and foot δ15N values was much greater for in G. aegis (4.8‰ ± 0.2 SE) compared with C. squamiferum.

The relationship between (a) δ13C or (b) δ15N and shell length (mm) in Gigantopelta aegis. Solid circles represent foot and the solid triangles represent the oesophageal gland. Grey shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals. The relationship between δ13C and shell length: foot δ13C = − 28.07951 + (shell length × 0.06120); oesophageal gland δ13C = ( − 28.07951 − 2.22308) + (shell length× 0.06120) The relationship between δ15N and shell length: foot δ15N = 7.66452 + (shell length× − 0.09983); oesophageal gland δ15N = (7.66452 − 4.75231) + (shell length× − 0.09983)

Southwest Indian ridge trophodynamics

δ13C ranged from − 32.6‰ (± 0.4 SD) in the foot of Bathymodiolus marisindicus to − 13.3‰ (± 2.1 SD) in Mirocaris indica (Table 1). Bathymodiolus marisindicus foot had the lowest δ15N values, − 7.6‰ (± 2.1 SD), while the muscle of Kiwa sp. SWIR had the highest δ15N value with 8.6‰ (Table 1). Model-based clustering indicated that the Longqi hydrothermal vent fauna fell into 4 clusters (Fig. 4). Bathymodiolus marisindicus was the only species in cluster 1 with the ellipse centred on − 32.6‰ (δ13C) and − 7.6‰ (δ15N). This cluster contained individuals with the lowest δ13C and δ15N values. Cluster 2 and cluster 3 represented those species with intermediate δ13C values. Cluster 2 was centred on − 22.3‰ (δ13C) and 4.4‰ (δ15N) and contained Chiridota sp. (Echinodermata; Holothuroidea), 4 out of the 5 C. squamiferum sampled and a single individual of N. marisindica. However, the classification of N. marisindica within this cluster 2 was within the quantile of highest uncertainty (95%). Cluster 3 contained G. aegis, N. marisindica and a single specimen of C. squamiferum. These individuals were centred on − 25.9‰ (δ13C) and 5.0‰ (δ15N). The remaining species, Kiwa sp. SWIR, Rimicaris kairei and Mirocaris indica (Crustacea; Malacostraca), were in cluster 4, centred on − 13.8‰ (δ13C) and 7.7‰ (δ15N). This cluster represented the species with the greatest δ13C and δ15N values.

δ13C and δ15N values for individual hydrothermal vent fauna collected from the Longqi vent field and the ellipses which indicate the results from the model-based clustering approach. The clusters contain the following macrofauna: cluster 1 includes Bathymodiolus marisindicus; cluster includes Chiridota sp., 4 out of the 5 Chyrsomallon squamiferum sampled and a single individual of Neolepas marisindica; cluster 3 includes Gigatopelta aegis, N. marisindica and a single specimen of C. squamiferum; cluster 4 includes Rimicaris kairei, Mirocaris indica and Kiwa sp. SWIR

Spatial differences in trophodynamics

The SEAc varied among the vent fields and was in good agreement with the mode of SEAb estimates (Fig. 5). SEAc was smallest at the E2 vent field (15.65‰2) and largest at the Longqi vent field (74.45‰2) (Table 2). Comparisons of SEAb indicated that there was a greater than 95% probability that E2 SEAb was smaller than Kairei, E9 and SWIR SEAb (Fig. 6) based on there being no overlap in the 95% CI (Table 2). Longqi vent field had the largest SEAb, which had a 95% probability of being larger than E9 but only a 75% probability of being larger than Kairei vent field (Fig. 6). Theta was very similar between E2 (0.17) and E9 (0.14) vent fields while it was much greater at Longqi (0.67) and Kairei (0.73) vent fields. This indicated that the inclination, and therefore the relationship between δ13C and δ15N, of the ellipse differed greatly between the ESR vent fields and both the Longqi and Kairei vent fields (Fig. 5). This was the result of the negative δ15N values that were observed at the Longqi and Kairei vent fields but were absent at the ESR locations.

The mode (solid black circle) of posterior Bayesian estimates of the standard ellipse area (SEAb) with 50, 75 and 95% credible intervals plotted in decreasing order of size calculated based on the δ13C and δ15N values of hydrothermal vent fauna collected at the East Scotia Ridge (E2 and E9), Longqi (SWIR) and Kairei (CIR) vent fields. The black x indicates the sample size-corrected standard ellipse area (SEAc)

Discussion

Gastropod size-based trophodynamics

Chrysomallon squamiferum showed no relationship between stable isotope values and shell length but G. aegis exhibited size-based trends in δ13C and δ15N values. The absence of a size-based relationship in δ13C and δ15N indicates that the diet is constant over the size range sampled in C. squamiferum. The sample size is small for C. squamiferum and it can be difficult to detect ecologically meaningful isotope size-based trends if the proportion of the total size range sampled is low (Galvan et al. 2010). The relationship between stable isotope values and size for C. squamiferum were consistent with those found at the Kairei hydrothermal vent field (Van Dover 2002). This indicates that the relationship between stable isotope values and shell length at Longqi vent field is likely to be similar. In contrast, G. aegis showed a positive relationship between the δ13C and shell length while there was a negative relationship between δ15N and shell length. Size-based δ13C and δ15N trends are also observed in the closely related Gigantopelta chessoia (Reid et al. 2016). Gigantopelta chessoia trends are potentially the result of ecophysiological interactions between the substrate depletion and the endosymbiont (Reid et al. 2016) that may be linked to variability in microbial cell density which can influence isotopic discrimination (Kampara et al. 2009). Other hydrothermal vent fauna including endosymbiotic hosting species show size-based stable isotope relationships (Trask and Van Dover 1999; De Busserolles et al. 2009; Reid et al. 2016). These may be related to a number of mechanisms including: CO2 limitation in the endosymbionts (Fisher et al. 1990); an increase in the diffusion distance for CO2 to travel from the environment through the host to the endosymbiont (Trask and Van Dover 1999); and a shift in the community structure of the endosymbiont community (De Busserolles et al. 2009). It is not clear whether dissolved organic matter in the diffuse flow fluids is a further source of nutrition; Bathymodiolus azoricus gains a proportion of its nutrition from dissolved organic matter uptake (Riou et al. 2010). It may be that free amino acids in the diffuse flow are a source of carbon and nitrogen for hydrothermal vent organisms and that the relative contribution to the overall carbon and nitrogen pool varies with body size. Experimentation will be required to better understand what is driving these size-based trends in δ13C and δ15N in C. squamiferum and G. aegis.

There were consistent tissue-isotope differences observed between the foot and the oesophageal gland in C. squamiferum and G. aegis, regardless of shell length. There were also species-level differences between foot and the oesophageal gland for δ15N but not δ13C. The differences between these two tissues may reflect differences in the routing of dietary macromolecules and/ or the biochemical composition of the tissue which is known to vary amongst tissues in hydrothermal vent fauna (Pranal et al. 1995; Pruski et al. 1998). This difference in routing pathways occurs when an individual gains its dietary protein and non-protein (e.g. carbohydrates) from separate sources (Martínez del Rio et al. 2009). Bathymodiolus azoricus gains a proportion of its nutrition from suspension feeding and dissolved organic matter uptake (Riou et al. 2010). Given that both C. squamiferum and G. aegis are supported by endosymbionts and morphological examination suggests that they are not feeding on free-living bacteria as adults, it is unlikely that they are utilising multiple food sources but the role of dissolved organic matter as a nutritional source cannot be ruled out. These species do differ in external morphological features with C. squamiferum carrying proteinaceous dermal sclerites on their foot (Chen et al. 2015a). The isotopic fractionation of amino acids in gastropods is known to depend on the balance between energy production and the construction of proteins for growth and additional proteinaceous mucus (Choi et al. 2018). Those species with higher proteinaceous mucus production have smaller differences in δ15N between muscle and mucus (Choi et al. 2018). This additional production of proteinaceous material in C. squamiferum may result in lower δ15N values and smaller differences between tissues. The result is that the difference between the δ15N values of the foot and oesophageal gland for these species may be the result of physiological processes and biochemical composition of the tissue rather than purely trophic interactions (Okada et al. 2019).

Southwest Indian Ridge trophodynamics

The δ13C values of the macrofauna associated with the Longqi hydrothermal vent indicated that they were using carbon fixed via the CBB (~ − 35‰ to ~ − 20‰) and rTCA (~ − 16‰ to ~ − 10‰) cycles while δ15N covered a range of 16.2‰. Within this broad range of δ13C and δ15N values, the hydrothermal vent fauna fell into 4 different clusters. Bathymodiolus marisindicus was the sole species in cluster 1. The δ13C values indicated that the endosymbionts were sulphur-oxidizing bacteria using the CBB cycle (~ − 30‰ to ~ − 20‰) and most probably the form I ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase/ oxygenase (RubisCO) (Petersen and Dubilier 2009). Bathymodiolus marisindicus gills and foot δ13C values were at the upper range of the values expected of the CBB cycle and may have also contained contributions of organic carbon produced by methane oxidizers. Dual endosymbiosis is known for B. aff. brevior at the Kairei and Edmond hydrothermal vent fields at the CIR (McKiness and Cavanaugh 2005). The SWIR B. marisindicus δ13C values are similar to those to other bathymodiolid mussels that include dual sulphur- and methane-oxidizing endosymbionts from the CIR (Van Dover 2002, Yamanaka et al. 2015) and the Okinawa Trough (Yamanaka et al. 2015). Bathymodiolus marisindicus was the only species to have negative δ15N values. Hydrothermal vent bathymodiolid mussel δ15N values range between ~ − 17‰ (Robinson et al. 1998) and ~ 6‰ (Limen & Juniper 2006), with the Longqi vent field samples being approximately in the middle of this range. The variability among different hydrothermal vent fields for bathymodiolid δ15N is likely a combination of several biological and chemical factors. These include differences in concentrations of inorganic nitrogen source (e.g. N2, NH4, NO3-), which inorganic substrate the endosymbionts use to produce organic material and the role of internal nitrogen cycling within the host (Liao et al. 2014; Ferrier-Pages and Leal 2019).

Cluster 2 contained C. squamiferum, Chiridota sp., and a single individual of N. marisindica. The δ13C values of individuals ranged from − 23.7‰ to − 21.5‰, which indicated that these individuals were feeding on organic carbon fixed via the CBB cycle. The δ13C values are within the range expected for carbon fixed via RubisCO form II and potentially other autochthonous vent carbon sources including carbon fixed via RubisCO form I and allochthonous photosynthetic primary production entering the system (Erickson et al. 2009; Hügler and Sievert 2011; Reid et al. 2013). In the case of C. squamiferum, the δ13C values and known endosymbiotic relationship with Gammaproteobacteria at CIR vent fields (Goffredi et al. 2004; Nakagawa et al. 2014) indicated that this species is dependent on locally fixed carbon. The δ13C values for C. squamiferum at Longqi (~ − 23‰) were less than those found at Kairei vent field (~ 18‰) indicating some potential mechanism influencing the stable isotope values between these locations. This potentially means that differences in the δ13C values may be related differences in the δ13C values of the inorganic carbon substrate used to fix organic carbon between hydrothermal vent fields or differences in temperature regimes which can influence trophic fractionation and isotopic turnover rates (Power et al. 2003; Martínez del Rio et al. 2009). In contrast to C. squamiferum, Chiridota sp. and N. marisindica are likely to consume free-living bacteria and particulate organic matter (POM). Chiridota hydrothermica has large lobe like tentacles, which are hypothesized to allow this species to shift between suspension- and deposit-feeding (Smirnov et al. 2000). The tentacle morphology is yet to be described in Chiridota sp. from the SWIR. The stable isotope values indicate that they may be consuming a heterogeneous mix of POM and free-living bacteria, which would be similar to the trophic guild based on the morphology of C. hydrothermica. Neolepas marisindica may potentially use a combination of suspension feeding or consume epibionts attached to their cirri as believed to occur in other hydrothermal vent stalked barnacles (Suzuki et al. 2009; Buckeridge et al. 2013; Reid et al. 2013). The δ13C values indicate that the carbon assimilated from their diet is potentially a mix of carbon produced via CBB and rTCA cycles. However, the role of photosynthetic primary production in the diet cannot be ruled out for Chiridota sp. and N. marisindica without the use of δ34S (Erickson et al. 2009; Reid et al. 2013).

Gigantopelta aegis, the majority of N. marisindica and single specimen of C. squamiferum formed cluster 3. The δ13C values within this cluster ranged from − 27.5‰ to − 24.1‰, which indicated that carbon was fixed via the CBB cycle (Hügler and Sievert 2011). These δ13C values were lighter than those in cluster 2 indicating that the predominant pathway for carbon fixation was potentially via RubisCO form I. The δ13C values of the endosymbiont hosting gastropods, G. aegis and C. squamiferum, would imply that they house Gammaproteobacteria in their oesophageal gland. This class of bacteria are found in the oesophageal gland of the closely related species G. chessoia from the ESR (Heywood et al. 2017) with G. chessoia endosymbiont being similar to that of C. squamiferum (Goffredi et al. 2004; Heywood et al. 2017). However, G. aegis and the majority of C. squamiferum were found in separate clusters within this analysis, which was largely dictated by differences in δ13C rather than δ15N. Gigantopelta aegis and C. squamiferum were sampled at different distances from the vent fluid source with C. squamiferum dominating diffuse flow areas closer to the vent opening and then G. aegis occupying the next distinctive faunal assemblage (Copley et al. 2016). This potentially means that differences in the δ13C values may be related to spatial differences in the δ13C values of the inorganic carbon substrate used to fix organic carbon. δ13C values of dissolved inorganic carbon in vent effluent can vary by up to ~ 1.5‰ across diffuse flow areas (Reid et al. 2013), which is less than the difference between G. aegis and C. squamiferum. Therefore, other mechanisms may also be driving differences in δ13C values including metabolic differences among these endosymbionts (Beinart et al. 2019) or differences in the isotopic fractionation of inorganic carbon during uptake by the host (Ferrier-Pages and Leal 2019).

Neolepas marisindica was another dominant member of cluster 3 with its δ13C values reflecting that of the CBB cycle. The δ13C values from Longqi vent field were similar to the ESR Neolepas scotianesis (Reid et al. 2013) but lower than the stalked barnacles from the Kairei vent field (Neolepas sp. δ13C = ~ − 16‰) (Van Dover 2002) and Brothers Caldera vent field (V. osheai, δ13C = ~ − 12‰) (Suzuki et al. 2009). Distance from the fluid source is known to result in differences in δ13C values for POM (Levesque et al. 2005) and the composition of epibiont communities on macrofauna (Zwirglmaier et al. 2015). Vulcanolepas osheai occur close to where vent fluid escapes from the seafloor leading to a high proportion of Epsilonproteobacteria (Suzuki et al. 2009), which will fix carbon via the rTCA cycle. Neolepas marisindica at Longi and N. scotianesis at ESR vents both occupy peripheral areas of hydrothermal vent fields (Marsh et al. 2012; Copley et al. 2016). The absence of dense bacteria on the cirri of N. scotianesis and the morphological structure indicated that this species is potentially a suspension feeder (Buckeridge et al. 2013; Reid et al. 2016). The similarity in spatial position in the vent field and their δ13C values indicate that N. marisindica may be more dependent on suspended POM than any potential epibionts growing on their cirri. However, there was a ~ 2‰ difference in the δ13C and δ15N values between the individuals of N. marisindica occurring in cluster 2 and 3. These were sampled at different locations, which may be related to the within-field variability in δ13C and δ15N value of POM (Levesque et al. 2005) as can be seen in N. scotianesis between northern and southern sections of the E9 vent field on the ESR (Reid et al. 2013).

Cluster 4 contained the mobile fauna Kiwa sp. SWIR, R. kairei and M. indica. These species can be found associated with structures emitting high-temperature fluids and in low-temperature diffuse flow areas (Copley et al. 2016). The δ13C values of these fauna fell within the range observed for the rTCA cycle (Hügler and Sievert 2011). Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei were sampled from diffuse flow areas of the Longqi vent field and their δ13C values were very similar (~ − 15‰). The closely related K. tyleri from the ESR and Rimicaris exoculata are known to be in epibiont–host association with Epsilonproteobacteria (Petersen et al. 2010; Zwirglmaier et al. 2015) and their δ13C values range between − 19.4‰ and − 10.6‰ (Reid et al. 2013) and − 15.8‰ to − 9.8‰ (Polz et al. 1998; Colaço et al. 2002), respectively. It is likely, given the δ13C values of Longqi species, that Epsilonproteobacteria are a dominant component of the epibiont community for Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei. The δ13C values of Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei are at the lower end of the range observed for these genera and it is likely that the collection from diffuse flow areas means that Gammaproteobacteria, which fix carbon via the CBB cycle, are also part of their epibiont communities. Given the small sample size collected from the Longqi vent field, however, it is difficult to ascertain how representative these samples are of the vent field, as both δ13C and δ15N values can change with body size, life history stage (Van Dover 2002; Reid et al. 2016) and between high and low-temperature areas of the vent field (Reid et al. 2013). In contrast, a larger sample size was collected for Mirocaris indica from structures associated with high-temperature fluid flow. This had the highest δ13C values of all the Longqi vent fauna ( − 13.3‰) and was at the higher end of the spectrum in relation to Mirocaris fortunata and Mirocaris keldyshi from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge ( − 19.8‰ to − 12.8‰) (Colaço et al. 2002; De Busserolles et al. 2009). POM on active hydrothermal vent chimneys can fall within the δ13C range observed in M. indica (Limen and Juniper 2006; Lang et al. 2012; Jaeschke et al. 2014). Mirocaris indica mouthparts suggest this species is grazing on POM attached to the hard-substrate and similar to M. fortunata, they are not using their mouthparts to grow epibionts for food (Komai et al. 2006).

Spatial differences in trophodynamics

Differences in the food web metrics were observed among the four hydrothermal vents examined. A difference was observed in the community isotopic niche area, as described by SEAb, which was smallest at E2 and largest at Longqi vent fields. This may be a result of the lower sample size at Longqi vent field rather than the spread of stable isotope values for the vent fauna. The CIs for the Longqi vent field SEAb were much greater in comparison to the other three vent fields, meaning that there is higher uncertainty in the SEAb estimates compared to the other sites. However, it is likely that additional factors are also contributing to these differences. The primary driver is likely the vent fluid chemistry, which dictates the composition of the microbial communities (Campbell et al. 2013; Meier et al. 2016; Fortunato et al. 2018). Hydrothermal vent fauna consuming bacteria utilizing the rTCA cycle does not seem to be as prevalent in the diet of fauna at the E2 vent field compared to the other three locations. This is clearly observed in K. tyleri and Kiwa sp. SWIR, which at the E9 and Longqi vent fields have some of the heaviest δ13C values indicative of the rTCA cycle, whereas at E2 K. tyleri δ13C values were more indicative of carbon fixed via the CBB cycle (Reid et al. 2013). The difference between δ13C values of K. tyleri at E2 and E9 were likely the result of differences in the epibiont community composition, which may have been driven by differences in the hydrothermal vent fluid chemistry (Reid et al. 2013; Zwirglmaier et al. 2015). SEAb and theta also differed between the Indian Ocean and Southern Ocean vent fields. This was largely a result of a greater range in δ15N values at the Indian Ocean vent fields compared to the ESR sites. Bathymodiolus marisindicus had negative δ15N values, which were not present in species from the ESR nor were bathymodiolid mussels found on the ESR (Van Dover 2002; Rogers et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2013). These negative values also resulted in a difference in theta, which dictates the angle of the ellipses in relation to the x-axis. Although SEAb were largely comparable amongst E9, Longqi and Kairei vent fields, theta has clearly highlighted that there are differences in the relationship between δ13C and δ15N.

Interpreting differences in theta and SEAb in relation to trophic structure is more complicated. The use of SEAb and theta, here, indicates that at a “broad-brush” level there are potentially important differences in trophic interactions among species based on the fauna sampled for these analyses but it explains less about the trophic structure. Converting the δ15N values into an estimate of trophic position would potentially standardize the interpretation of δ15N across the four hydrothermal vent fields allowing greater insights into macroecological patterns in food web structure, rather than examining site-specific differences in stable isotope values (Olsson et al. 2009; Tran et al. 2015) or examining patterns of variability. However, estimating trophic position is difficult at hydrothermal vents given the potential high variability in δ15N of inorganic nitrogen compounds and the absence of organisms that could potentially act as a baseline (Bourbonnais et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2013; Winkel et al. 2014). This means that additional complementary data will have to be included in order to estimate trophic position including stomach content analysis, either through eDNA or identification, and behavioural observations. Even though the hydrothermal vent food webs are unlikely to host no more than 3 trophic levels (Reid et al. 2013; Lelievre et al. 2018), a number of the top-level predators are found on the periphery of the hydrothermal vent in diffuse flow areas (Marsh et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2013), which may be more at risk to habit destruction or modification through deep-sea mining. It is important that any food web metric that is potentially used as a comparative tool for understanding ecological differences in food web structure, system health or used as a baseline assessment prior to exploitation, is easily interpretable from an ecological or management perspective (Van Audenhaege et al. 2019).

The species and genera at the Longqi vent field, which overlapped with those present on the ESR and CIR occupied trophic niches that would be expected given the available ecological information known from these sites (Van Dover 2002; Marsh et al. 2012; Reid et al. 2013; Copley et al. 2016). However, there are clear differences in the relative contribution of different genera among these locations (Rogers et al. 2012; Copley et al. 2016) and as well as a degree of variation in their stable isotope values. The difference in δ13C values between G. chessoia (~ 30‰) and G. aegis (~ 26‰) may also be the result of different phylotypes of Gammaproteobacteria. A difference of ~ 3‰ among vent fields is also observed in the genus Alvinoconcha along the Eastern Lau Spreading Center, which contain different phylotypes of Gammaproteobacteria (Beinart et al. 2012). The difference in phylotypes is spatial inter-field differences but it is not clear whether there are intra-field differences as well (Beinart et al. 2012). The presence of B. marisindicus and C. squamiferum at SWIR may be limiting the distribution of G. aegis at Longqi compared to G. chessoia at the ESR where the lack of bathymodiolid mussels and C. squamiferum may result in a lower competitive pressure to occupancy the low-temperature diffuse flow areas. The successional stage of the hydrothermal vent may also be important because G. aegis appears in more abundant on predominantly diffuse flow vents with lower high-temperature activity (Copley et al. 2016). This contrasts with G. chessoia which is present on hydrothermal structures which contain both high- and low-temperature venting and just low-temperature venting (Marsh et al. 2012). This may result in G. aegis occupying a different physiochemical niche, either in space or time, than G. chessoia, which may ultimately influence the endosymbiont community or other processes that drive variation in δ13C values.

Even though there was a clear indication that the δ13C values of Longqi vent field macrofauna represented those fixed via the rTCA cycle, the observed abundances of Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei were low compared with the species of the same genera at ESR and CIR vent fields (Marsh et al. 2012; Copley et al. 2016). Kiwa tyleri and R. kairei are biomass-dominating taxa close to high-temperature vent orifices at ESR and CIR vent fields, respectively. Their biomass is supported by chemoautotrophic epibionts, which are predominantly Epsilonproteobacteria (Campbell and Cary 2004; Campbell et al. 2013). The first species at the Longqi vent field found in high abundance are C. squamiferum which are found close to diffuse venting fluids and had δ13C values indicative of the CBB cycle and are known to house Gammaproteobacteria at vent fields on the CIR (Goffredi et al. 2004). The result is that the proportion of carbon fixed by the CBB and rTCA cycles, which enters the metazoan food web to sustain the biomass, is potentially different. The underlying process for this is not clear. H2S, H2 and CH4 have been sampled from a high-temperature source at Longqi vent field (Ji et al. 2017; Tao et al. 2020) and the H2S concentrations are lower than found at the ESR (James et al. 2014). The concentration of sulphides in the environment are important determinants of whether Gamma- or Epsilonproteobacteria dominate, with high sulphide and H2 conditions resulting in a greater proportion of Epsilonproteobacteria (Nakagawa and Takai 2008; Beinart et al. 2012). If the geochemical environment is not appropriate for the growth of Epsilonproteobacteria in association with R. kairei then there is potentially a lack of food to sustain high populations. However, this may not explain the low numbers of Kiwa sp. SWIR because the epibiont community on the closely related K. tyleri can be dominated by Gammaproteobacteria (Zwirglmaier et al. 2015). The low abundance for both these species may be related to the dispersal ability of these two species rather than the geochemical environment at Longqi or a combination of both. It is not clear whether Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei are at the edge of their respective ranges, resulting in this region of the SWIR being a population sink. In this case, C. squamiferum has the potential to expand its ecological niche into parts of the hydrothermal vent field that in other CIR vent fields are dominated by R. kairei.

In conclusion, there is evidence of carbon fixed via the CBB and rTCA cycle entering the Longqi vent field food web. Several shared vent fauna, at genus level, show similar stable isotope values as those from other vent fields but there is a degree of isotopic variability among the locations. There is a clear requirement to undertake spatial characterization of microbial communities and define the physiochemical niches of hydrothermal vent fauna at Longqi vent field to put this trophodynamic investigation into greater context. Further work should investigate the food web at a higher spatial resolution and include sampling potential food sources like dissolved organic matter, particulate organic matter and free-living bacteria. Furthermore, there are differences in the observed abundance of some of these species and genera when comparing Longqi to the ESR and CIR vent fields. It is unclear why this may be occurring. It may be that Kiwa sp. SWIR and R. kairei do not reach high population abundances found at other vent fields for those taxa because these are sink populations, even though the highly developed chimney structures would suggest prolonged venting at Longqi vent field. The underlying ecological processes driving turnover of species along large-scale gradients and how this may result in differing trophic structure is still largely unknown. The interaction among dispersal ability, available habitat and nutritional resources within and among vent fields all need to be considered. This will require placing hydrothermal vent fields like the Longqi vent field into the wider ridge context with further exploration along the SWIR towards the CIR and Bouvet Triple Junction, but also require the incorporation of biological traits (Chapman et al. 2019) into any analyses on trophic structure.

References

Beinart RA, Luo CW, Konstantinidis KT, Stewart FJ, Girguis PR (2019) The bacterial symbionts of closely related hydrothermal vent snails with distinct geochemical habitats show broad similarity in chemoautotrophic gene content. Front Microbiol 10:13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01818

Beinart RA, Sanders JG, Faure B, Sylva SP, Lee RW, Becker EL, Gartman A, Luther GW, Seewald JS, Fisher CR, Girguis PR (2012) Evidence for the role of endosymbionts in regional-scale habitat partitioning by hydrothermal vent symbioses. PNAS 109:E3241–E3250. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1202690109

Bell JB, Reid WDK, Pearce DA, Glover AG, Sweeting CJ, Newton J, Woulds C (2017) Hydrothermal activity lowers trophic diversity in Antarctic hydrothermal sediments. Biogeosciences 14:5705–5725. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-14-5705-2017

Bourbonnais A, Lehmann MF, Butterfield DA, Juniper SK (2012) Subseafloor nitrogen transformations in diffuse hydrothermal vent fluids of the Juan de Fuca Ridge evidenced by the isotopic composition of nitrate and ammonium. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 13:Q02T01. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011gc003863

Buckeridge JS, Linse K, Jackson JA (2013) Vulcanolepas scotiaensis sp nov., a new deep-sea scalpelliform barnacle (Eolepadidae: Neolepadinae) from hydrothermal vents in the Scotia Sea. Antarctica Zootaxa 3745:551–568

Butterfield DA, McDuff RE, Mottl MJ, Lilley MD, Lupton JE, Massoth GJ (1994) Gradients in the composition of hydrothermal fluids from the endeavour segment vent field: phase separation and brine loss. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 99:9561–9583. https://doi.org/10.1029/93jb03132

Campbell BJ, Cary SC (2004) Abundance of reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle genes in free-living microorganisms at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:6282–6289. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.70.10.6282-6289.2004

Campbell BJ, Engel AS, Porter ML, Takai K (2006) The versatile epsilon-proteobacteria: key players in sulphidic habitats. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:458–468. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1414

Campbell BJ, Polson SW, Allen LZ, Williamson SJ, Lee CK, Wommack KE, Cary SC (2013) Diffuse flow environments within basalt- and sediment-based hydrothermal vent ecosystems harbor specialized microbial communities. Front Microbiol 4:15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00182

Caut S, Angulo E, Courchamp F (2009) Variation in discrimination factors (δ15N and δ13C): the effect of diet isotopic values and applications for diet reconstruction. J Appl Ecol 46:443–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01620.x

Chapman ASA, Beaulieu SE, Colaço A, Gebruk AV, Hilario A, Kihara TC, Ramirez-Llodra E, Sarrazin J, Tunnicliffe V, Amon DJ, Baker MC, Boschen-Rose RE, Chen C, Cooper IJ, Copley JT, Corbari L, Cordes EE, Cuvelier D, Duperron S, Du Preez C, Gollner S, Horton T, Hourdez S, Krylova EM, Linse K, LokaBharathi PA, Marsh L, Matabos M, Mills SW, Mullineaux LS, Rapp HT, Reid WDK, Rybakova E, A. Thomas TR, Southgate SJ, Stöhr S, Turner PJ, Watanabe HK, Yasuhara M, Bates AE (2019) sFDvent: a global trait database for deep-sea hydrothermal-vent fauna. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 28:1538–1551. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12975

Chen C, Copley JT, Linse K, Rogers AD, Sigwart J (2015a) How the mollusc got its scales: convergent evolution of the molluscan scleritome. Biol J Linn Soc 114:949–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/bij.12462

Chen C, Linse K, Roterman CN, Copley JT, Rogers AD (2015b) A new genus of large hydrothermal vent-endemic gastropod (Neomphalina: Peltospiridae). Zool J Linn Soc 175:319–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12279

Childress JJ, Fisher CR (1992) The biology of hydrothermal vent animals- physiology, biochemistry and autotrophic symbioses. Oceanogr Mar Biol 30:337–441

Choi B, Takizawa Y, Chikaraishi Y (2018) Compression of trophic discrimination in 15N/14N within amino acids for herbivrous gastropods. Res Org Geochem 43:29–35

Colaço A, Dehairs F, Desbruyères D (2002) Nutritional relations of deep-sea hydrothermal fields at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: a stable isotope approach. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 49:395–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-0637(01)00060-7

Copley JT, Marsh L, Glover AG, Huhnerbach V, Nye VE, Reid WDK, Sweeting CJ, Wigham BD, Wiklund H (2016) Ecology and biogeography of megafauna and macrofauna at the first known deep-sea hydrothermal vents on the ultraslow-spreading Southwest Indian Ridge. Sci Rep 6:13. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep39158

De Busserolles F, Sarrazin J, Gauthier O, Gélinas Y, Fabri MC, Sarradin PM, Desbruyères D (2009) Are spatial variations in the diets of hydrothermal fauna linked to local environmental conditions? Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr 56:1649–1664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.05.011

Dick GJ (2019) The microbiomes of deep-sea hydrothermal vents: distributed globally, shaped locally. Nat Rev Microbiol 17:271–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0160-2

Dick HJB, Lin J, Schouten H (2003) An ultraslow-spreading class of ocean ridge. Nature 426:405–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02128

Erickson KL, Macko SA, Van Dover CL (2009) Evidence for a chemoautotrophically based food web at inactive hydrothermal vents (Manus Basin). Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr 56:1577–1585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.05.002

Ferrier-Pages C, Leal MC (2019) Stable isotopes as tracers of trophic interactions in marine mutualistic symbioses. Ecol Evol 9:723–740. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.4712

Fisher CR, Childress JJ, Macko SA, Brooks JM (1994) Nutritional interactions in Galapagos Rift hydrothermal vent communities-inferences from stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 103:45–55

Fisher CR, Kennicutt MC, Brooks JM (1990) Stable carbon isotopic evidence for carbon limitation in hdyrothermal vent vestimentiferans. Science 247:1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.247.4946.1094

Fortunato CS, Larson B, Butterfield DA, Huber JA (2018) Spatially distinct, temporally stable microbial populations mediate biogeochemical cycling at and below the seafloor in hydrothermal vent fluids. Environ Microbiol 20:769–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14011

Galvan DE, Sweeting CJ, Reid WDK (2010) Power of stable isotope techniques to detect size-based feeding in marine fishes. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 407:271–278. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08528

German CR, Von Damm KL (2003) Hydrothermal processes. In: Elderfield H (ed) The ocean and marine geochemistry. Elsevier, Oxford, pp 181–222

Goffredi SK, Warén A, Orphan VJ, Van Dover CL, Vrijenhoek RC (2004) Novel forms of structural integration between microbes and a hydrothermal vent gastropod from the indian ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3082. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.5.3082-3090.2004

Guy RD, Fogel ML, Berry JA (1993) Photosynthetic fractions of eh stable isotopes of oxygen and carbon. Plant Phsiology 101:37–47

Henry MS, Childress JJ, Figueroa D (2008) Metabolic rates and thermal tolerances of chemoautotrophic symbioses from Lau Basin hydrothermal vents and their implications for species distributions. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 55:679–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2008.02.001

Herrera S, Watanabe H, Shank TM (2015) Evolutionary and biogeographical patterns of barnacles from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Mol Ecol 24:673–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.13054

Heywood JL, Chen C, Pearce DA, Linse K (2017) Bacterial communities associated with the Southern Ocean vent gastropod, Gigantopelta chessoia: indication of horizontal symbiont transfer. Polar Biol 40:2335–2342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-017-2148-6

Hügler M, Sievert SM (2011) Beyond the calvin cycle: autotrophic carbon fixation in the ocean. Ann Rev Mar Sci 3:261–289. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142712

Jackson AL, Inger R, Parnell AC, Bearhop S (2011) Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER–Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J Anim Ecol 80:595–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01806.x

Jaeschke A, Eickmann B, Lang SQ, Bernasconi SM, Strauss H, Fruh-Green GL (2014) Biosignatures in chimney structures and sediment from the Loki’s Castle low-temperature hydrothermal vent field at the Arctic Mid-Ocean Ridge. Extremophiles 18:545–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00792-014-0640-2

James RH, Green DRH, Stock MJ, Alker BJ, Banerjee NR, Cole C, German CR, Huvenne VAI, Powell AM, Connelly DP (2014) Composition of hydrothermal fluids and minerology of associated chimney matetial on the East Scotia Ridge back-arc spreading centre. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 139:47–71

Ji F, Zhou H, Yang Q, Gao H, Wang H, Lilley MD (2017) Geochemistry of hydrothermal vent fluids and its implications for subsurface processes at the active Longqi hydrothermal field, Southwest Indian Ridge. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 122:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2017.02.001

Kampara M, Thuller M, Harms H, Wick LY (2009) Impact of cell density on microbially induced stable isotope fractionation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81:977–985

Karl DM (1995) Ecology of free-living, hydrothermal vent microbial communities. In: Karl DM (ed) The microbiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, pp 35–124

Kelley DS, Karson JA, Fruh-Green GL, Yoerger DR, Shank TM, Butterfield DA, Hayes JM, Schrenk MO, Olson EJ, Proskurowski G, Jakuba MV, Bradley A, Larson B, Ludwig K, Glickson D, Buckman K, Bradley AS, Brazelton WJ, Roe KK, J EM, Delacour A, Bernasconi SM, Lilley MD, Baross JA, Summons RT, Sylva SP (2005) A serpentinite-hosted ecosystem: the lost city hydrothermal field. Science 307:1428–1434

Komai T, Martin JW, Zala K, Tsuchida S, Hashimoto J (2006) A new species of Mirocaris (Crustacea: Decapoda: Caridea: Alvinocarididae) associated with hydrothermal vents on the Central Indian Ridge, Indian Ocean. Sci Mar 70:109. https://doi.org/10.3989/scimar.2006.70n1109

Lang SQ, Fruh-Green GL, Bernasconi SM, Lilley MD, Proskurowski G, Mehay S, Butterfield DA (2012) Microbial utilization of abiogenic carbon and hydrogen in a serpentinite-hosted system. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 92:82–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2012.06.006

Lelievre Y, Sarrazin J, Marticorena J, Schaal G, Day T, Legendre P, Hourdez S, Matabos M (2018) Biodiversity and trophic ecology of hydrothermal vent fauna associated with tubeworm assemblages on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Biogeosciences 15:2629–2647. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-15-2629-2018

Levesque C, Limen H, Juniper SK (2005) Origin, composition and nutritional quality of particulate matter at deep-sea hydrothermal vents on Axial Volcano, NE Pacific. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 289:43–52. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps289043

Liao L, Wankel SD, Wu M, Cavanaugh CM, Girguis PR (2014) Characterizing the plasticity of nitrogen metabolism by the host and symbionts of the hydrothermal vent chemoautotrophic symbioses Ridgeia piscesae. Mol Ecol 23:1544–1557. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12460

Limen H, Juniper SK (2006) Habitat controls on vent food webs at Eifuku Volcano, Mariana Arc. Cah Biol Mar 47(4):449–455

Marsh L, Copley JT, Huvenne VAI, Linse K, Reid WDK, Rogers AD, Sweeting CJ, Tyler PA (2012) Microdistribution of faunal assemblages at deep-sea hydrothermal vents in the Southern Ocean. PLoS ONE 7:e48348. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0048348

Martínez del Rio C, Wolf N, Carleton SA, Gannes LZ (2009) Isotopic ecology ten years after a call for more laboratory experiments. Biol Rev 84:91–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00064.x

McCollom TM, Shock EL (1997) Geochemical constraints on chemolithoautotrophic metabolism by microorganisms in seafloor hydrothermal systems. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:4375–4391

McKiness ZP, Cavanaugh CM (2005) The ubiquitous mussel: Bathymodiolus aff. brevior symbiosis at the Central Indian Ridge hydrothermal vents. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 295:183–190

Meier DV, Bach W, Girguis PR, Gruber-Vodicka HR, Reeves EP, Richter M, Vidoudez C, Amann R, Meyerdierks A (2016) Heterotrophic Proteobacteria in the vicinity of diffuse hydrothermal venting. Environ Microbiol 18:4348–4368. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.13304

Nakagawa S, Shimamura S, Takaki Y, Suzuki Y, Murakami S, Watanabe T, Fujiyoshi S, Mino S, Sawabe T, Maeda T, Makita H, Nemoto S, Nishimura SI, Watanabe H, Watsuji TO, Takai K (2014) Allying with armored snails: the complete genome of gammaproteobacterial endosymbiont. ISME J 8:40–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.131

Nakagawa S, Takai K (2008) Deep-sea vent chemoautotrophs: diversity, biochemistry and ecological significance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00502.x

Newsome SD, del Rio CM, Bearhop S, Phillips DL (2007) A niche for isotopic ecology. Front Ecol Environ 5:429–436. https://doi.org/10.1890/060150.01

Okada S, Chen C, Watsuji T-o, Nishizawa M, Suzuki Y, Sano Y, Bissessur D, Deguchi S, Takai K (2019) The making of natural iron sulfide nanoparticles in a hot vent snail. PNAS 116:20376–20381. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908533116

Olsson K, Stenroth P, Nyström PER, Granéli W (2009) Invasions and niche width: does niche width of an introduced crayfish differ from a native crayfish? Freshw Biol 54:1731–1740. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02221.x

Petersen JM, Dubilier N (2009) Methanotrophic symbioses in marine invertebrates. Environ Microbiol Rep 1:319–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00081.x

Petersen JM, Ramette A, Lott C, Cambon-Bonavita MA, Zbinden M, Dubilier N (2010) Dual symbiosis of the vent shrimp Rimicaris exoculata with filamentous gamma- and epsilonproteobacteria at four Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vent fields. Environ Microbiol 12:2204–2218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02129.x

Peterson BJ, Fry B (1987) Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 18:293–320

Podowski EL, Ma SF, Luther GW, Wardrop D, Fisher CR (2010) Biotic and abiotic factors affecting distributions of megafauna in diffuse flow on andesite and basalt along the Eastern Lau Spreading Center, Tonga. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 418:25–45. https://doi.org/10.3354/meps08797

Polz MF, Robinson JJ, Cavanaugh CM, Van Dover CL (1998) Trophic ecology of massive shrimp aggregations at a Mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vent site. Limn Oceanogr 43:1631–1638. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1998.43.7.1631

Portail M, Olu K, Dubois SF, Escobar-Briones E, Gelinas Y, Menot L, Sarrazin J (2016) Food-web complexity in Guaymas Basin hydrothermal vents and cold seeps. PLoS ONE 11:e0162263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162263

Post DM (2002) Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology 83:703–718

Power M, Guiguer KRRA, Barton DR (2003) Effects of temperature on isotopic enrichment in Daphnia magna: implications for aquatic food-web studies. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 17:1619–1625

Pranal V, Fiala-Médioni A, Colomines JC (1995) Amino acid and related compound composition in two symbiotic mytilid species from hydrothermal vents. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 119:155–166

Pruski AM, Fiala-Médioni A, Boulègue J, Colomines JC (1998) Sulphur-amino acids in symbiotic species from hdyrothermal vents and cold seeps. Cah Biol Mar 39(3):321–324

Reid WDK, Sweeting CJ, Wigham BD, McGill RAR, Polunin NVC (2016) Isotopic niche variability in macroconsumers of the East Scotia Ridge (Southern Ocean) hydrothermal vents: what more can we learn from an ellipse? Mar Ecol Prog Ser 542:13–24

Reid WDK, Sweeting CJ, Wigham BD, Zwirglmaier K, Hawkes JA, McGill RAR, Linse K, Polunin NVC (2013) Spatial differences in East Scotia Ridge hydrothermal vent food webs: influences of chemistry, microbiology and predation on trophodynamics. PLoS ONE 8:e65553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0065553

Riou V, Colaco A, Bouillion S, Khripounoff A, Dando PR, Mangion P, Chevalier E, Korntheuer M, Santos RS, Dehairs F (2010) Mixotrophy in the deep sea: a dual endosymbiotic hydrothermal mytilid assimilates dissolved and particulate organic matter. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 405:187–201

Robinson JJ, Scott KM, Swanson ST, O’Leary MH, Horken K, Tabita FR, Cavanaugh CM (2003) Kinetic isotope effects and characterisation of form II RubisCO from the chemoautotrophic endosymbionts of the hydrothermal vent tubeworm Riftia pachyptila. Limn Oceanogr 48:48–54

Robinson JJ, Polz MF, Fiala-Medioni A, Cavanaugh CM (1998) Physiological and immunological evidence for two distinct C-1-utilizing pathways in Bathymodiolus puteoserpentis (Bivalvia: Mytilidae), a dual endosymbiotic mussel from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Marine Biol 132(4):625–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270050427

Rogers AD, Tyler PA, Connelly DP, Copley JT, James R, Larter RD, Linse K, Mills RA, Garabato AN, Pancost RD, Pearce DA, Polunin NVC, German CR, Shank T, Boersch-Supan PH, Alker BJ, Aquilina A, Bennett SA, Clarke A, Dinley RJJ, Graham AGC, Green DRH, Hawkes JA, Hepburn L, Hilario A, Huvenne VAI, Marsh L, Ramirez-Llodra E, Reid WDK, Roterman CN, Sweeting CJ, Thatje S, Zwirglmaier K (2012) The discovery of new deep-sea hydrothermal vent communities in the southern ocean and implications for biogeography. PLoS Biol 10:17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001234

Sarrazin J, Juniper SK, Massoth G, Legendre P (1999) Physical and chemical factors influencing species distributions on hydrothermal sulfide edifices of the Juan de Fuca Ridge, northeast Pacific. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 190:89–112

Sarrazin J, Legendre P, de Busserolles F, Fabri MC, Guilini K, Ivanenko VN, Morineaux M, Vanreusel A, Sarradin PM (2015) Biodiversity patterns, environmental drivers and indicator species on a high-temperature hydrothermal edifice, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr 121:177–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.04.013

Scott KM (2003) A delta C-13-based carbon flux model for the hydrothermal vent chemosynthetic symbiosis Riftia pachyptila predicts sizeable CO2 graidents at the host-symbiont interface. Environ Microbiol 5:424–432

Scott KM, Schwedock J, Schrag DP, Cavanaugh CM (2004) Influence of form IA RubisCO and environmental dissolved inorganic carbon on the delta C-13 of the clam-chemoautotroph symbiosis Solemya velum. Environ Microbiol 6:1210–1219

Scrucca L, Fop M, Murphy TB, Raftery AE (2016) mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. The R J 8:205–233

Sievert SM, Vetriani C (2012) Chemoautotrophy at deep-sea vents past, present, and future. Oceanography 25:218–233. https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2012.21

Smirnov AV, Gebruk AV, Galkin SV, Shank T (2000) New species of holothurian (Echinodermata: Holothuroidea) from hydrothermal vent habitats. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 80:321–328. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025315499001897

Staudigel H, Hart SR, Pile A, Bailey SE, Baker ET, Brooke S, Connelly DP, Haucke L, German CR, Hudson IR, Jones D, Koppers APP, Konter J, Lee R, Pietsch TW, Tebo BM, Templeton AS, Zierenberg R, Young CM (2006) Vailulu’u seamount, Samoa: life and death on an active submarine volcano. PNAS 103:6448–6453

Suzuki Y, Suzuki M, Tsuchida S, Takai K, Horikoshi K, Southward AJ, Newman WA, Yamaguchi T (2009) Molecular investigations of the stalked barnacle Vulcanolepas osheai and the Epibiotic bacteria from the Brothers Caldera, Kermadec Arc, New Zealand. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 89:727–733. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315409000459

Tao C, Li H, Jin X, Zhou J, Wu T, He Y, Deng X, Gu C, Zhang G, Liu W (2014) Seafloor hydrothermal activity and polymetallic sulfide exploration on the southwest Indian ridge. Chin Sci Bull 59:2266–2276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-014-0182-0

Tao C, Seyfield WE Jr, Lowell RP, Liu Y, Liang J, Guo Z, Ding K, Zhang H, Liu J, Qiu L, Egorov I, Liao S, Zhao M, Zhou J, Deng X, Li H, Wang H, Cai W, Zhang G, Zhou H, Lin J, Li W (2020) Deep high-temperature hydrothermal circulation in a detachment faulting system on the ultra-slow spreadign ridge. Nat Commun 11:1300. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15062-w

Tao C, Wu G, Li H, Han X, German CR, Lin J, Zhou N, Guo S, Zhu J, Chen YJ, Yoerger DR, Su X, Parties D-S (2012) First active hydrothermal vents on an ultraslow-spreading center: Southwest Indian Ridge. Geology 40:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1130/g32389.1

Tivey MK (2007) Generation of seafloor hydrothermal vent fluids and associated mineral deposits. Oceanography 20:50–65

Tran TNQ, Jackson MC, Sheath D, Verreycken H, Britton JR (2015) Patterns of trophic niche divergence between invasive and native fishes in wild communities are predictable from mesocosm studies. J Anim Ecol 84:1071–1080. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12360

Trask JL, Van Dover CL (1999) Site-specific and ontogenetic variations in nutrition of mussels (Bathymodiolus sp.) from the lucky strike hydrothermal vent field. Mid-Atlantic Ridge Limn Oceanogr 44:334–343. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1999.44.2.0334

Tunnicliffe V, Juniper SK, Sibuet M (2003) Reducing environments of the deep-sea floor. In: Tyler PA (ed) Ecosystems of the Deep Ocean. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, pp 81–110

Van Audenhaege L, Fariñas-Bermejo A, Schultz T, Lee Van Dover C (2019) An environmental baseline for food webs at deep-sea hydrothermal vents in Manus Basin (Papua New Guinea). Deep Sea Res Part I: Oceanogr Res Pap 148:88–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2019.04.018

Van Dover C (2002) Trophic relationships among invertebrates at the Kairei hydrothermal vent field (Central Indian Ridge). Mar Biol 141:761–772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-002-0865-y

Van Dover CL, Fry B (1994) Microorganisms as food resources at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Limn Oceanogr 39:51–57. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1994.39.1.0051

Winkel M, de Beer D, Lavik G, Peplies J, Mussmann M (2014) Close association of active nitrifiers with Beggiatoa mats covering deep-sea hydrothermal sediments. Environ Microbiol 16:1612–1626. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.12316

Yamamoto M, Takai K (2011) Sulfur metabolisms in epsilon- and gamma-proteobacteria in deep-sea hydrothermal fields. Front Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00192

Yamanaka T, Shimamura S, Nagashio H, Yamagami S, Onishi Y, Hyodo A, Mampuku M, Mizota C (2015) A compilation of the stable isotopic compositions of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur in soft body parts of animals collected from deep-sea hydrothermal vent and methane seep fields: variations in energy source and importance of subsurface microbial processes in the sediment-hosted systems. In: Ishibashi J-I, Okino K, Sunamura M (eds) Subseafloor biosphere linked to hydrothermal systems: TIAGA concept. Springer, Tokyo, pp 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54865-2_10

Zhou Y, Zhang D, Zhang R, Liu Z, Tao C, Lu B, Sun D, Xu P, Lin R, Wang J, Wang C (2018) Characterization of vent fauna at three hydrothermal vent fields on the Southwest Indian Ridge: implications for biogeography and interannual dynamics on ultraslow-spreading ridges. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 137:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2018.05.001

Zwirglmaier K, Reid WDK, Heywood J, Sweeting CJ, Wigham BD, Polunin NVC, Hawkes JA, Connelly DP, Pearce D, Linse K (2015) Linking regional variation of epibiotic bacterial diversity and trophic ecology in a new species of Kiwaidae (Decapoda, Anomura) from East Scotia Ridge (Antarctica) hydrothermal vents. MicrobiologyOpen 4:136–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.227

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the officers, crew, scientists and GEOMAR ROV KEIL 6000 team on board the RRS James Cook during JC67. The research expedition was funded by NERC through grant NE/H012087/1 to J.C. The stable isotope analysis was funded by NERC research grant NE/D01249X/1 (Chemosynthetically-driven ecosystems south of the Polar Front: biogeography and ecology) and Newcastle University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed by WDKR, BDW, LM and JTC. The field work was carried out by LM and JTC. The sample preparation was undertaken by WDKR and JNJW. The data analysis was conducted by WDKR and YZ. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethic approval

All applicable international, national and/or institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed. All invertebrates sampled in this study were non-cephalopod.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: H. J. T. Hoving.

Reviewed by A. Colaco and Y. Zhou.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reid, W.D.K., Wigham, B.D., Marsh, L. et al. Trophodynamics at the Longqi hydrothermal vent field and comparison with the East Scotia and Central Indian Ridges. Mar Biol 167, 141 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03755-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-020-03755-1