Abstract

Summary

This scoping review described the use, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness of clinical fracture-risk assessment tools to prevent future osteoporotic fractures among older adults. Results show that the screening was not superior in preventing all osteoporosis-related fractures to usual care. However, it positively influenced participants’ perspectives on osteoporosis, may have reduced hip fractures, and seemed cost-effective.

Purpose

We aim to provide a synopsis of the evidence about the use of clinical fracture-risk assessment tools to influence health outcomes, including reducing future osteoporotic fractures and their cost-effectiveness.

Methods

We followed the guidelines of Arksey and O’Malley and their modifications. A comprehensive search strategy was created to search CINAHL, Medline, and Embase databases until June 29, 2021, with no restrictions. We critically appraised the quality of all included studies.

Results

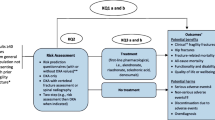

Fourteen studies were included in the review after screening 2484 titles and 68 full-text articles. Four randomized controlled trials investigated the effectiveness of clinical fracture-risk assessment tools in reducing all fractures among older women. Using those assessment tools did not show a statistically significant reduction in osteoporotic fracture risk compared to usual care; however, additional analyses of two of these trials showed a trend toward reducing hip fractures, and the results might be clinically significant. Four studies tested the impact of screening programs on other health outcomes, and participants reported positive results. Eight simulation studies estimated the cost-effectiveness of using these tools to screen for fractures, with the majority showing significant potential savings.

Conclusion

According to the available evidence to date, using clinical fracture-risk assessment screening tools was not more effective than usual care in preventing all osteoporosis-related fractures. However, using those screening tools positively influenced women’s perspectives on osteoporosis, may have reduced hip fracture risk, and could potentially be cost-effective. This is a relatively new research area where additional studies are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kingkaew P, Maleewong U, Ngarmukos C, Teerawattananon Y (2012) Evidence to inform decision makers in Thailand: a cost-effectiveness analysis of screening and treatment strategies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Value Health 15(1 Suppl):S20-28

Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L, Behzadi MH, Rabieenia E, Shohaimi S, Mohammadi M (2021) The global prevalence of osteoporosis in the world: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 16(1):1–20

Sozen T, Ozisik L, Basaran NC (2017) An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol 4(1):46–56

Government of Canada (2021) Osteoporosis and related fractures in Canada. City.

Leibson CL, Tosteson ANA, Gabriel SE, Ransom JE, Melton LJ (2002) Mortality, disability, and nursing home use for persons with and without hip fracture: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 50(10):1644–1650

Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, de Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, van Leeuwen JP, Pols HA (2004) Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 34(1):195–202

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, Cooper C, McCloskey EV (2014) Epidemiology and Quality of Life Working Group of, I. O. F. Worldwide uptake of FRAX. Arch Osteoporos 9(1):166

Fraser LA, Langsetmo L, Berger C, Ioannidis G, Goltzman D, Adachi JD, Papaioannou A, Josse R, Kovacs CS, Olszynski WP, Towheed T, Hanley DA, Kaiser SM, Prior J, Jamal S, Kreiger N, Brown JP, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA, Leslie WD, G CaMos Research (2011) Fracture prediction and calibration of a Canadian FRAX(R) tool: a population-based report from CaMos. Osteoporos Int 22(3):829–837

Leslie WD, Lix LM, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey E, Kanis JA, P Manitoba Bone Density (2010) Independent clinical validation of a Canadian FRAX tool: fracture prediction and model calibration. J Bone Miner Res 25(11):2350–2358

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5(1):69

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tuncalp O, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473

Kanis JA, Hans D, Cooper C, Baim S, Bilezikian JP, Binkley N, Cauley JA, Compston JE, Dawson-Hughes B, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Johansson H, Leslie WD, Lewiecki EM, Luckey M, Oden A, Papapoulos SE, Poiana C, Rizzoli R, Wahl DA, McCloskey EV, FI Task Force of the (2011) Interpretation and use of FRAX in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 22(9):2395–2411

Garvan Institute of Medical Research (2008) Bone Fracture Risk Calculator. City.

Siminoski K, Leslie WD, Frame H, Hodsman A, Josse RG, Khan A, Lentle BC, Levesque J, Lyons DJ, Tarulli G, Brown JP (2007) Recommendations for bone mineral density reporting in Canada: a shift to absolute fracture risk assessment. J Clin Densitom 10(2):120–123

Nayak S, Roberts MS, Greenspan SL (2011) Cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med 155(11):751–761

Shepstone L, Lenaghan E, Cooper C, Clarke S, Fong-Soe-Khioe R, Fordham R, Gittoes N, Harvey I, Harvey N, Heawood A, Holland R, Howe A, Kanis J, Marshall T, O’Neill T, Peters T, Redmond N, Torgerson D, Turner D, McCloskey E, SS Team (2018) Screening in the community to reduce fractures in older women (SCOOP): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 391(10122):741–747

Rubin KH, Rothmann MJ, Holmberg T, Hoiberg M, Moller S, Barkmann R, Gluer CC, Hermann AP, Bech M, Gram J, Brixen K (2018) Effectiveness of a two-step population-based osteoporosis screening program using FRAX: the randomized Risk-stratified Osteoporosis Strategy Evaluation (ROSE) study. Osteoporos Int 29(3):567–578

Merlijn T, Swart KM, van Schoor NM, Heymans MW, van der Zwaard BC, van der Heijden AA, Rutters F, Lips P, van der Horst HE, Niemeijer C, Netelenbos JC, Elders PJ (2019) The effect of a screening and treatment program for the prevention of fractures in older women: a randomized pragmatic trial. J Bone Miner Res 34(11):1993–2000

Lacroix AZ, Buist DS, Brenneman SK, Abbott TA 3rd (2005) Evaluation of three population-based strategies for fracture prevention: results of the osteoporosis population-based risk assessment (OPRA) trial. Med Care 43(3):293–302

Rothmann MJ, Huniche L, Ammentorp J, Barkmann R, Gluer CC, Hermann AP (2014) Women’s perspectives and experiences on screening for osteoporosis (Risk-stratified Osteoporosis Strategy Evaluation, ROSE). Arch Osteoporos 9(1):192

Dunniway DL, Camune B, Baldwin K, Crane JK (2012) FRAX(R) counseling for bone health behavior change in women 50 years of age and older. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 24(6):382–389

Ito K, Leslie WD (2015) Cost-effectiveness of fracture prevention in rural women with limited access to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. Osteoporos Int 26(8):2111–2119

Walter E, Dellago H, Grillari J, Dimai HP, Hack M (2018) Cost-utility analysis of fracture risk assessment using microRNAs compared with standard tools and no monitoring in the Austrian female population. Bone 108:44–54

Chandran M, Ganesan G, Tan KB, Reginster JY, Hiligsmann M (2021) Cost-effectiveness of FRAX(R)-based intervention thresholds for management of osteoporosis in Singaporean women. Osteoporos Int 32(1):133–144

Martin-Sanchez M, Comas M, Posso M, Louro J, Domingo L, Tebe C, Castells X, Espallargues M (2019) Cost-Effectiveness of the screening for the primary prevention of fragility hip fracture in spain using FRAX((R)). Calcif Tissue Int 105(3):263–270

Soini E, Riekkinen O, Kroger H, Mankinen P, Hallinen T, Karjalainen JP (2018) Cost-effectiveness of pulse-echo ultrasonometry in osteoporosis management. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 10:279–292

Su Y, Lai FTT, Yip BHK, Leung JCS, Kwok TCY (2018) Cost-effectiveness of osteoporosis screening strategies for hip fracture prevention in older Chinese people: a decision tree modeling study in the Mr. OS and Ms. OS cohort in Hong Kong. Osteoporos Int 29(8):1793–1805

Papaioannou A, Kennedy CC, Ioannidis G, Sawka A, Hopman WM, Pickard L, Brown JP, Josse RG, Kaiser S, Anastassiades T, Goltzman D, Papadimitropoulos M, Tenenhouse A, Prior JC, Olszynski WP, Adachi JD, G CaMos Study (2009) The impact of incident fractures on health-related quality of life: 5 years of data from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 20(5):703–714

Auais M, Morin SN, Finch L, Ahmed S, Mayo N (2018) Toward a meaningful definition of recovery after hip fracture: comparing two definitions for community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 99(6):1108–1115

Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, Hauer K (2015) Factors associated with fear of falling and associated activity restriction in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 23(1):72–86

Lewiecki EM (2005) Clinical applications of bone density testing for osteoporosis. Minerva Med 96(5):317–330

Osteoporosis Canada (2015) Make the FIRST break the LAST with Fracture Liasion Services. City.

Osteoporosis Canada (2016) Better Bone Health: 2015–2016 annual report. City.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Ms. Paola Durando MLS, AHIP, Health Sciences Librarian, Queen's University Library, who helped with creating and performing the search strategy. We would like to also thank Yuan Chen and Tiffany Wing Lam for helping in screening articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable

Conflicts of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search Strategies for three databases

Medline | |

|---|---|

Search terms | Results |

1 frax.mp | 1484 |

2 garvan.mp | 65 |

3 qfracture.mp | 42 |

4 caroc.mp | 22 |

5 (fracture* adj5 risk assessment*).mp | 1639 |

6 risk assessment*.mp | 327,007 |

7 Risk Assessment/ | 283,558 |

8 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 | 327,557 |

9 osteoporosis/ or osteopSearchorosis, postmenopausal/ | 57,951 |

10 osteoporosis.mp | 91,742 |

11 osteoporotic fracture*.mp | 11,997 |

12 fragility fracture*.mp | 4084 |

13 hip fractures/ or femoral neck fractures/ | 25,509 |

14 hip fracture*.mp | 24,547 |

15 or/9–14 | 120,913 |

16 8 and 15 | 5482 |

17 limit 16 to humans | 5070 |

18 limit 17 to yr = “2000–current” | 4864 |

19 limit 18 to dt = 20,180,701–20,210,629 | 762 |

20 fracture risk scale*.mp | 6 |

21 19 or 20 | 766 |

Embase | |

|---|---|

Search terms | Results |

1 frax.mp | 4017 |

2 garvan.mp | 154 |

3 qfracture.mp | 110 |

4 caroc.mp | 46 |

5 (fracture* adj5 risk assessment*).mp | 3185 |

6 risk assessment*.mp | 651,218 |

7 risk assessment/ | 619,253 |

8 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 | 653,210 |

9 exp osteoporosis/ | 143,291 |

10 osteoporosis.mp | 170,261 |

11 osteoporotic fracture*.mp | 13,188 |

12 fragility fracture*.mp | 22,012 |

13 exp hip fracture/ | 42,826 |

14 hip fracture*.mp | 37,422 |

15 or/9–14 | 208,790 |

16 8 and 15 | 16,518 |

17 limit 16 to human | 15,890 |

18 limit 17 to yr = “2000–current” | 15,084 |

19 limit 18 to dc = 20,180,701–20,210,629 | 4114 |

20 fracture risk scale*.mp | 8 |

21 19 or 20 | 4118 |

22 limit 21 to (books or chapter or conference abstract or conference paper or “conference review” or editorial) | 1898 |

23 21 not 22 | 2220 |

CINAHL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Search ID# | Search terms | Search options | Results |

S16 | S14 OR S15 | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 497 |

S15 | “fracture risk scale*” | Limiters—Published Date: 20,180,701–20,210,731; Human Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 1 |

S14 | S8 AND S13 | Limiters—Published Date: 20,180,701–20,210,731; Human Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 497 |

S13 | S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 33,588 |

S12 | (MH “Hip Fractures”) | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 10,843 |

S11 | “fragility fracture*” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 1,400 |

S10 | (MH “Osteoporotic Fractures”) | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 629 |

S9 | (MH “Osteoporosis + ”) | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 23,589 |

S8 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 124,629 |

S7 | “risk assessment” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 124,231 |

S6 | (MH “Risk Assessment”) | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 116,820 |

S5 | “fracture risk assessment*” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 376 |

S4 | “caroc” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 6 |

S3 | “qfracture” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 17 |

S2 | “garvan” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 199 |

S1 | “frax” | Expanders—Apply related words; Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | 523 |

Appendix 2. PEDro Scales completed for the RCT studies

PEDro Criteria | LaCroix, 2005 | Shepstone, 2017 | Rubin, 2017 | Merlijn, 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1. Eligibility criteria were specified | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

2. Subjects were randomly allocated to groups (in a crossover study, subjects were randomly allocated an order in which treatments were received) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

3. Allocation was concealed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

4. The groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

5. There was blinding of all subjects | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

6. There was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

7. There was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

8. Measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

9. All subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by “intention to treat” | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

10. The results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

11. The study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Overall PEDro Score | 5/10 | 6/10 | 5/10 | 7/10 |

Appendix 3. CASP tool for qualitative studies

CASP tool | Dunniway,2010 | Rothman,2014 |

|---|---|---|

Section A: Are the results valid | ||

1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes |

2. Is a qualitative methodology appropriate | Yes | Yes |

3. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes |

4. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | Yes | Yes |

5. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Yes | Yes |

6. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered | No | Unclear |

Section B: What are the results? | ||

7. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | Unclear | Yes |

8. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Yes | Yes |

9. Is there a clear statement of findings? | Yes | Yes |

Section C: Will the results help locally? | ||

10. How valuable is the research | Page 7 | Page 8 |

Appendix 4. CHEERS for economical evaluations

CHEERS 2022 Checklist | Studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Item # | Items | Guidance for Reposting | Nayak, 2011 | Kingkaew, 2011 | Ito,2015 | Walter, 2017 | Soini, 2018 | Su, 2018 | Martin-Sanchez, 2019 | Chandra, 2020 |

1 | Title | Identify the study as an economic evaluation and specify the interventions being compared | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

2 | Abstract | Provide a structured summary that highlights context, key methods, results, and alternative analyses | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

3 | Background and objectives | Give the context for the study, the study question, and its practical relevance for decision-making in policy or practice | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

4 | Health economic analysis plan | Indicate whether a health economic analysis plan was developed and where available | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

5 | Study population | Describe characteristics of the study population (such as age range, demographics, socioeconomic, or clinical characteristics) | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

6 | Setting and location | Provide relevant contextual information that may influence findings | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

7 | Comparators | Describe the interventions or strategies being compared and why chosen | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

8 | Perspective | State the perspective(s) adopted by the study and why chosen | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

9 | Time horizon | State the time horizon for the study and why appropriate | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

10 | Discount rate | Report the discount rate(s) and reason chosen | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported |

11 | Selection of outcomes | Describe what outcomes were used as the measure(s) of benefit(s) and harm(s) | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

12 | Measurement of outcomes | Describe how outcomes used to capture benefit(s) and harm(s) were measured | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

13 | Valuation of outcomes | Describe the population and methods used to measure and value outcomes | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

14 | Measurement and valuation of resources and costs | Describe how costs were valued | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

15 | Currency, price date, and conversion | Report the dates of the estimated resource quantities and unit costs, plus the currency and year of conversion | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported |

16 | Rationale and description of model | If modeling is used, describe in detail and why used. Report if the model is publicly available and where it can be accessed | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

17 | Analytics and assumptions | Describe any methods for analyzing or statistically transforming data, any extrapolation methods, and approaches for validating any model used | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

18 | Characterizing heterogeneity | Describe any methods used for estimating how the results of the study vary for sub-groups | Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

19 | Characterizing distributional effects | Describe how impacts are distributed across different individuals or adjustments made to reflect priority populations | Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

20 | Characterizing uncertainty | Describe methods to characterize any sources of uncertainty in the analysis | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

21 | Approach to engagement with patients and others affected by the study | Describe any approaches to engage patients or service recipients, the general public, communities, or stakeholders (e.g., clinicians or payers) in the design of the study | Not Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Not Reported |

22 | Study parameters | Report all analytic inputs (e.g., values, ranges, references) including uncertainty or distributional assumptions | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

23 | Summary of main results | Report the mean values for the main categories of costs and outcomes of interest and summarize them in the most appropriate overall measure | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

24 | Effect of uncertainty | Describe how uncertainty about analytic judgments, inputs, or projections affect findings. Report the effect of choice of discount rate and time horizon, if applicable | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

25 | Effect of engagement with patients and others affected by the study | Report on any difference patient/service recipient, general public, community, or stakeholder involvement made to the approach or findings of the study | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

26 | Study findings, limitations, generalizability, and current knowledge | Report key findings, limitations, ethical or equity considerations not captured, and how these could impact patients, policy, or practice | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

27 | Source of funding | Describe how the study was funded and any role of the funder in the identification, design, conduct, and reporting of the analysis | Reported | Reported | Not Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

28 | Conflicts of interest | Report authors conflicts of interest according to journal or International Committee of Medical Journal Editors requirements | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported | Reported |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Auais, M., Angermann, H., Grubb, M. et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of clinical fracture-risk assessment tools in reducing future osteoporotic fractures among older adults: a structured scoping review. Osteoporos Int 34, 823–840 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-022-06659-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-022-06659-6