Abstract

Summary

The probability of initiating with anti-osteoporosis therapy increased from 7 % in 2000 to 46 % in 2010. This improvement was greater for patients over the age of 75 years. Men, those overweight, having dementia or exposed to antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics or opioid analgesics were significantly less likely to receive anti-osteoporosis drugs.

Introduction

The objective of this study was to examine trends and determinants of anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing after hip fracture in the UK between 2000 and 2010.

Methods

Data were extracted from the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink for patients ≥50 years who had a first hip fracture between 2000 and 2010 and who did not currently (≤6 months prior) receive anti-osteoporosis drugs (bisphosphonates, strontium ranelate, parathyroid hormone, calcitonin and raloxifene) (n = 27,542). The cumulative incidence probability of being prescribed anti-osteoporosis drugs within 1 year after hip fracture was estimated by Kaplan-Meier life-table analyses. Determinants for treatment initiation were estimated by Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

The probability of being prescribed any anti-osteoporosis drug after hip fracture increased from 7 % in 2000 to 46 % in 2010. This trend was more marked in patients ≥75 years. The increase in prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs was complemented by a similar increase in vitamin D/calcium provision. Cumulative incidence of receiving anti-osteoporosis therapy was greater at any given point in time in women (8 % in 2000, 51 % in 2010) compared to men (4 % in 2000, 34 % in 2010). In addition to male gender, multivariable Cox regression identified reduced likelihood of receiving anti-osteoporosis drugs for those being overweight, having dementia and exposed to psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics) or opioid analgesics.

Conclusion

Although the prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs after hip fracture has increased substantially since 2000, the overall rate remained inadequate, particularly in men. With the continuing increase in the absolute number of hip fractures, further research should be made into the barriers to optimise osteoporosis management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a growing public health issue affecting an estimated 2.8 million people within the UK [1]. Osteoporosis results in fragility fractures, the most serious of which are hip fractures. In the last decade, absolute numbers of hospital admissions for hip fractures have increased by 15.5 %, despite age- and sex-standardised rates remaining stable since 2003 [2]. A history of hip fracture increases the risk of future fracture 3.2 times when compared to patients without a hip fracture [3], and this risk is greatest in the first year and remains elevated for at least 5 years [4, 5].

Hence, post-fracture treatment with anti-osteoporosis drugs is important to prevent the occurrence of new fragility fractures. Over the decade 2000–2010, the therapies available for treatment of osteoporosis have changed markedly. Initially, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was the first-line osteoporosis treatment [6]. However, since the Woman’s Health Initiative trial in 2002 demonstrated that the risk of coronary heart disease, pulmonary embolism, stroke and breast cancer was greater than the benefits conferred by this therapy, its use has been limited to the short-term relief of menopausal symptoms [7]. Since then, bisphosphonates have been the mainstay of treatment for osteoporosis. Bisphosphonates have been shown to reduce the risk of hip fractures by 30–50 % and vertebral fractures by 30–70 % [8]. From 2005 onwards, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has also endorsed the use of raloxifene, teriparatide, strontium ranelate and calcitonin (although now withdrawn) for secondary fracture prevention. Despite these readily available, effective treatments, a care gap in pharmacological prevention of subsequent fractures has been documented worldwide [9–11].

Given the ageing population and therefore the increasing number of hip fractures, it is important to know the trend in prescribing practice for anti-osteoporosis drugs and to identify patients at risk of not receiving these drugs. Fortunately, several, but not all, studies have shown an improvement in anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing between the late 1990s and the first half of the twenty-first century, where few studies have investigated prescribing practices over more recent years [12–20] or have concerned concomitant prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs with vitamin D and/or calcium supplements [21–23]. The latter is important since clinical trials demonstrating efficacy of anti-osteoporosis drugs were all conducted among participants receiving adequate levels of calcium and vitamin D. In 2010, a national clinical audit in the UK showed that as many as 40 % of all hip fracture patients did not receive any form of anti-osteoporosis drug treatment within 12 weeks [24]. Numbers for concomitant or solely prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs and calcium/vitamin D were not provided, and prescribing practices were not presented beyond age and gender while other patient characteristics may influence prescribing practice as well. Individual data linking drug prescribing and patient characteristics (e.g. previous fractures, lifestyle variables, co-morbidities, poly-pharmacy) would greatly assist in determining which patient groups are at increased risk of not receiving anti-osteoporosis drug treatment after hip fracture.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the trends in prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs and co-prescribing with vitamin D/calcium supplements in hip fracture patients, who were not currently in receipt of anti-osteoporosis drugs, within a primary care setting in the UK between 2000 and 2010. Additionally, we aimed to examine which patient characteristics influenced the initialisation of anti-osteoporosis drug treatment.

Methods

Source population

The population was sourced from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) which contains anonymised electronic health records from 625 primary care practices from across the UK representing around 8 % of the population. The records include details of all diagnoses and prescriptions issued by NHS general practitioners, specialist referrals, hospital admissions and lifestyle variables (e.g. body mass index, smoking status) for community-dwelling, but not institutionalized, patients.

Study population

The study population comprised patients aged ≥50 years who suffered an incident hip fracture between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010 and who did not receive a prescription for any anti-osteoporosis drug (bisphosphonates, calcitonin, strontium ranelate, raloxifene, parathyroid hormone analogues [teriparatide]) in the 6 months prior to the index hip fracture. A 6-month period was chosen since previous studies have shown that the vast majority of patients who stop with anti-osteoporosis treatment restart their treatment within 6 months [25] and is also in line with previous studies [16]. To ensure that the hip fracture was the first hip fracture, patients with a record of non-specified fractures any time prior to the index hip fracture date were excluded. Approval for this study was given by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for MHRA Database Research (protocol number 13_113, amendment 2).

Outcome

The outcome of interest was a prescription for an anti-osteoporosis drug in the year following hip fracture. This was defined as a prescription for either: bisphosphonates (alendronic acid, risedronic acid, ibandronic acid, etidronic acid and zoledronic acid), calcitonin, strontium ranelate, raloxifene or parathyroid hormone analogues (teriparatide) based upon the NICE guidelines for secondary osteoporosis treatment [26]. Additionally, prescribing trends for calcium/vitamin D (separately and in combination with anti-osteoporosis drugs) and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) were described. Patients were followed from the date of index hip fracture until the date of the first prescription or censoring, whichever came first. Patients were censored upon death, exit from the database or end of the follow-up period (365 days after the index hip fracture, 31 December 2011 at the latest).

Determinants

Factors identified as potential determinants for anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing were largely based on risk factors for osteoporosis or fracture: age; sex; smoking status (non-smoker, ex-smoker, current smoker, missing); the most recent record of body mass index ([BMI]; <18, 18–25, >25 kg/m2, missing); history of major fracture (clinical vertebrae, forearm, humerus); falls (3–12 months before); a history of secondary osteoporosis in accordance with the FRAX definition [27]; inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis); rheumatoid arthritis; Parkinson’s disease; cerebrovascular disease; ischaemic heart disease; and the use in the 6 months prior of corticosteroids, antipsychotics, antidepressants, opioid analgesics stronger than tramadol, anticonvulsants and benzodiazepines and other sedatives/hypnotics or calcium/vitamin D. In addition to these, a history of dementia or malignant neoplasms and the total number of different prescriptions (poly-pharmacy) in the 6 months prior to hip fracture may also influence prescribing practice. Indication for osteoporosis treatment is historically based on bone mineral density (BMD); however, this data is not routinely available within the CPRD and so could not be included in this analysis.

Statistical analysis

Sex-specific descriptive characteristics were calculated at baseline. Kaplan-Meier life-table analyses were used to estimate the cumulative incidence probability for receiving a prescription for anti-osteoporosis drugs within 1 year of hip fracture. The analysis was done separately for each calendar year and stratified by age categories (50–74, 75–84, ≥85 years), region (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland) and sex. We also examined prescribing trends over time for the individual drug classes, type of bisphosphonate, and for calcium/vitamin D both separately and in combination with anti-osteoporosis drugs. For the latter analysis, patients were required to not have received both anti-osteoporosis drugs and calcium/vitamin D in the 6 months before hip fracture.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to identify which factors (including the year of index hip fracture) were determinants of anti-osteoporosis drug initiation. Since for some of the covariates’ (BMI, smoking status) missing data were present, multiple imputation was used to create five imputed datasets. Analyses were performed separately for the five imputed datasets, and hazard ratios (HRs) were pooled using the MIANALYZE procedure. All analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS, Cary NC, USA).

Results

Trends in anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing

Over the 10-year period, 30,516 patients aged 50 years or older suffered a hip fracture. Of these, 2974 (9.7 %) had received at least one prescription for anti-osteoporosis drugs in the 6 months prior to the index fracture. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study population. The median age (interquartile range) was 83 (76–88) and 79 years (71–85) for females and males, respectively.

After index hip fracture, 6684 patients received some form of anti-osteoporosis therapy, of which 94 % of the prescriptions were for bisphosphonates. The mean time to receiving a prescription was 88 days (SD80). The remaining patients, 20,858 (68 %), had no record of receiving osteoporosis medication in either the 6 months prior or in the year following hip fracture.

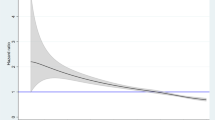

During the study period, there was a steady rise in anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing following a hip fracture. Among patients who were not currently on treatment, the probability of receiving an anti-osteoporosis drug increased from 7.4 % in 2000 to 45.5 % in 2010. Cumulative incidence of receiving anti-osteoporosis drugs was greater at any given point in time in women compared to men. The proportion of women that was prescribed an anti-osteoporosis drug in 2000 was 8.2 % and increased to 51.3 % in 2010. These numbers were 4.1 and 33.6 % for men, respectively. By 2010, a female hip fracture patient was 1.5 times more likely to be prescribed an anti-osteoporosis drug when compared to males (Fig. 1a). Figure 1b demonstrates that this trend also differed between age categories, with a more pronounced trend for patients aged 75 years and older than for those under the age of 75 years, particularly after 2005 where the prescribing rates continued to increase for the older population but stabilised for patients under the age of 75 years. Figure 1c shows that there was a general improvement in anti-osteoporosis prescribing for all four UK regions (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), but levels of prescribing varied considerable across these regions. From 2008, theses rates diverged with an increase in Northern Ireland and a decrease in Scotland.

Evaluation of the medication classes individually demonstrated a substantial rise in the prescribing of bisphosphonates within 1 year after hip fracture (Fig. 2a). Figure 2b shows the trend in the prescribing of bisphosphonates, stratified by the type of bisphosphonate. Alendronic acid was the most frequently prescribed bisphosphonate followed by risedronic acid, and after 2006, this disparity became markedly greater. Zoledronic acid was not included in the figure as numbers were too low (n = 2). Finally, from Fig. 3, it can be seen that there has been a dramatic increase in the combined prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs together with vitamin D/calcium supplementation.

Determinants of anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing

Multivariable Cox regression identified increased likelihood of being prescribed an anti-osteoporosis drug after hip fracture for increasing calendar year, female sex (adj. HR = 1.74, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.64–1.86), rheumatoid arthritis (HR = 1.26, 95 % CI 1.11–1.42) and the presence of secondary osteoporosis (HR = 1.13, 95 % CI 1.03–1.26), corticosteroid use and a history of major osteoporotic fracture. When compared to patients younger than 60 years, patients between the ages of 60–90 years were significantly more likely to receive osteoporosis therapy. Conversely, having dementia, a BMI >25 kg/m2 or using antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics, or opioid analgesics were negatively associated with the initiation of osteoporosis therapy (Table 2).

Discussion

The last decade has seen a striking change in prescribing practices for anti-osteoporosis drugs following a hip fracture. The probability of initiating anti-osteoporotic treatment has increased dramatically, particularly for patients over the age of 75 years. It was also apparent that the initiation of anti-osteoporosis drugs was paired with the initiation of calcium/vitamin D supplementation. However, this encouraging trend slowed down from 2006 onwards. Ultimately, the overall prescribing rate has remained inadequate with just over 50 % of hip fracture patients not receiving any anti-osteoporosis drug in 2010. The factors which were associated with reduced likelihood of receiving anti-osteoporosis drug therapy were male gender, being overweight, having dementia or exposed to certain psychotropic drugs (antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics) or opioid analgesics.

Our findings of a steady increase in the prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs up until 2005 are consistent with most studies performed in other countries [15–19] and form an extension to the study performed on the former version of the CPRD (GPRD) for the period 1991–2005 by Watson et al. [20]. The pattern of anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing may be reflective of changes in bisphosphonate formulation, advice from various committees and changes to NHS guidelines. As from 2005, there was a pronounced difference in prescribing of anti-osteoporosis medications between patients under and over 75 years. This is most likely a consequence of the NICE Technology Appraisal 87 published in 2005 [28], which advocated the use of anti-osteoporosis therapies without the need for prior dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanning for women over the age of 75 years who had already suffered a hip fracture. This, however, does not explain why the prescribing rate plateaued for those <75 years. We have no clear explanation for this phenomenon, but it may be partly related to the actual proportion of hip fractures that was attributable to osteoporotic BMD. This proportion has been reported to a range between 28 and 64 %, depending on age and sex [29, 30]. Since DXA-derived diagnosis of osteoporosis has been the cornerstone for indicating anti-osteoporosis drug therapy, an increase in DXA referrals may not necessarily have resulted in a further increase in anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing as osteoporosis may subsequently not have been diagnosed for many younger hip fracture patients. Furthermore, the cost of anti-osteoporotic drugs has been reduced further since the release of generic forms of alendronic acid in August 2005. Subsequently, NICE guidance (TA161) endorsed alendronic acid as the first-line therapy. This resulted in the stabilisation in the prescribing of risedronic acid in 2005 whose use then went into decline [26]. The majority of anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing was paired with the prescribing of vitamin D/calcium supplements which is in line with clinical guidelines. Another UK study that was conducted in 2006 among nine general practitioner practices showed that 34 % of patients were co-prescribed calcium and/or vitamin D with anti-osteoporosis drugs [23]. This coincides well with our results with a cumulative incidence probability of 39 % in 2006. Unfortunately, there was a considerable number of patients who only received vitamin D/calcium supplementation.

Inline with the results by Wang et al. [31], we found a slowing down in the increasing prescribing trend from 2006 onwards, while an Australian study showed a decline between 2007 and 2010 [32]. Reasons for the stagnation or even decline in anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing may coincide with revised labelling of bisphosphonates for risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw in 2005 and reports for increased risk of atypical femoral fractures and atrial fibrillation, with increasing publicity in the years thereafter. A US study showed a decline in use of anti-osteoporosis drugs after hip fracture from 2002 onwards (40.2 % in 2002 to 20.5 % in 2011) [12]. Together with the possible influence of safety issue reports, this could have been attributed to a fragmented health care system with a lack of, or insufficient, communication between emergency/orthopaedic departments and outpatient care for follow-up osteoporosis assessment. A service model to bridge this gap, the Fracture Liaison Service (FLS), now exists for over a decade in the UK which has proven to reduce the care gap for secondary fracture prevention [33]. However, this care model has been developed in 27 % of UK NHS Hospital Trusts prior to 2006, which has barely increased to 29 % by 2009. This is in line with the flattening in prescribing rates for this period.

Few studies have examined which factors lead to the initiation of anti-osteoporosis drugs after hip fracture. Many of the factors which increase the risk of fracture were also significant determinants for initiation of anti-osteoporosis drug therapy. Hence, female gender, increasing age (except for very old age), a history of major osteoporotic fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, secondary osteoporosis and the use of corticosteroids all increased the likelihood of receiving osteoporosis treatment which is in line with previous studies [12, 34–37]. Conversely, patients who were suffering from mental illness (i.e. using antipsychotics, sedatives and hypnotics or having dementia) or patients who were overweight or used opioid analgesics were less likely to receive osteoporosis therapy. Other factors which have been associated with the initiation of anti-osteoporosis drug treatment are patients’ self-perception of osteoporosis risk [34] and their appraisal for their treatment need [38], but these could not be identified in our data. The fact that an increasing number of prescriptions was not inversely associated with the instigation of osteoporosis therapy was unexpected given the findings of Duyvendak et al. [39] who found that poly-pharmacy was a barrier to osteoporosis treatment in long-term corticosteroid users. The study of Solomon et al. [12] even found an increased likelihood of being prescribed anti-osteoporosis drugs with increasing number of prescriptions which was also conducted among hip fracture patients. Consistent with other findings is the observation that male hip fracture patients were less likely to be prescribed anti-osteoporosis drugs than female patients [12, 16, 40]. The difference in prescribing patterns between men and women is likely partly due to osteoporosis primarily being considered a health problem of older women [41, 42], rather than of men; consequently, men often have poor knowledge of the condition and therefore do not consider themselves as susceptible [43, 44] and hence would not consider asking their GP for treatment. Furthermore, the number of clinical trials examining the effect of bisphosphonates on fracture reduction in men is limited, where the majority of trials used change in bone mineral density (BMD) as the primary end point [45, 46]. The few trials into the effects of bisphosphonate use on fracture reduction in men and lack of clinical guidance for anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing for men may explain why GPs do not habitually provide bisphosphonate treatment to men. However, seeing as the bisphosphonate has a similar effect on bone turnover and density in both men and women, the difference in prescribing habits is likely unjustified.

We studied a large community-dwelling population representative of the UK as a whole. However, there are several limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of our results. By studying hip fracture patients, we have assumed that all of our study population was eligible for anti-osteoporosis medication according to a confirmed diagnosis of osteoporosis, while this may not necessarily have been the case. BMD measurements are not routinely available in the CPRD which limits our interpretation as to the eligibility for treatment. Additionally, it is possible that some fractures were pathological or due to trauma. Furthermore, we have only considered initial prescription rates and did not include repeat prescriptions. Therefore, we cannot make any comments regarding adherence with treatment. It is well known that a large proportion of patients do not adhere to their treatment regimen, although the exact reasons for this phenomenon remain poorly understood [47]. Zoledronic acid as well as PTH analogues (teriparatide) and denosumab are not fully captured in CPRD records as this database only includes prescriptions issued by general practitioners and not specialists. This may have resulted in an underestimate of anti-osteoporosis therapy initiation. However, denosumab became available in the UK at the end of the study period (2010), and although we cannot directly estimate the magnitude of this limitation for PTH analogues and zoledronic acid, indirect evidence from other countries has shown that the utilisation of these drugs remained limited until the year 2010 [12, 32]. Furthermore, NICE guidance places teriparatide under restrictive conditions for the secondary prevention of fragility fractures. Similarly, data for non-prescription over-the-counter vitamin D or calcium were not available in our database, which may have resulted in an underestimate of use of these drugs. Finally, the generalisability of this study is limited to free-living individuals as it excluded those who were institutionalized. Just under 10 % of the patients transferred out of the database, most likely to nursing homes where prescribing practices could differ.

In conclusion, our study has shown that although the prescribing rate for anti-osteoporosis medications has increased substantially since 2000, the overall rate in 2010 was still markedly inadequate. This was particularly so in men, where the prescribing of anti-osteoporosis drugs was notably less than that observed in women at any given point in time. Other patient characteristics that were associated with decreased likelihood of receiving anti-osteoporosis drugs were being overweight, having dementia and exposed to antipsychotics, sedatives/hypnotics or opioid analgesics. Increase in the prescribing of anti-osteoporosis medications may be facilitated by recent major advances in risk assessment, such as the FRAX calculator [48], linked to treatment thresholds, as exemplified by the UK NOGG Guidelines [49]. There is much work to promote secondary fracture prevention services [50], notably by the current International Osteoporosis Foundation Capture the Fracture initiative [51]. With the absolute number of hip fractures expected to increase inexorably across the world over coming decades, our findings clearly demonstrate the acute need for such activity and for the generally increased awareness of osteoporosis and prevention of fragility fracture.

References

National osteoporosis society, URL: http://www.nos.org.uk/page.aspx?pid=328 Accessed 22 January 2015

Smith P, Ariti C, Bardsley M (2013) Focus on hip fracture: trends in emergency admission for fractured neck of femur, 2001 to 2011. Nuffield Trust/Health Foundation, London

Warriner AH, Patkar NM, Yun H, Delzell E (2012) Minor, major, low-trauma, and high-trauma fractures: what are the subsequent fracture risks and how do they vary? Curr Osteoporos Rep 10:22–27

von Friesendorff M, Besjakov J, Akesson K (2008) Long-term survival and fracture risk after hip fracture: a 22-year follow-up in women. J Bone Miner Res 23:1832–1841

van Geel TA, van Helden S, Geusens PP, Winkens B, Dinant GJ (2009) Clinical subsequent fractures cluster in time after first fractures. Ann Rheum Dis 68:99–102

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)/Committee on Safety of Medicines (2004) Review of the evidence on long-term safety of HRT. Curr Probl Phamacovigilance 30:4–6

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, Kotchen JM, Ockene J, Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:321–333

Reginster JY (2011) Antifracture efficacy of currently available therapies for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Drugs 71:65–78

Formiga F, Rivera A, Nolla JM, Coscujuela A, Sole A, Pujol R (2005) Failure to treat osteoporosis and the risk of subsequent fractures in elderly patients with previous hip fracture: a five year retrospective study. Aging Clin Exp Res 17:96–99

Rabenda V, Vanoverloop J, Fabri V, Mertens R, Sumkay F, Vannecke C, Deswaef A, Verpooten GA, Reginster JY (2008) Low incidence of anti-osteoporosis treatment after hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:2142–2148

Giangregorio L, Papaioannou A, Cranney A, Zytaruk N, Adachi JD (2006) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap: an international phenomenon. Semin Arthritis Rheum 35:293–305

Solomon DH, Johnston SS, Boytsov NN, McMorrow D, Lane JM, Krohn KD (2014) Osteoporosis medication use after hip fracture in U.S. patients between 2002 and 2011. J Bone Miner Res 29:1929–1937

McGowen B, Bennet K, Casey MC, Doherty J, Silke C, Whelan B (2013) Comparison of prescribing and adherence patterns of anti-osteoporotic medications post-admission for fragility type fracture in an urban teaching hospital and a rural teaching hospital in Ireland between 2005–2008. Ir J Med Sci 182:601–608

Fisher A, Martin J, Srikusalanukul W, Davis M (2010) Bisphosphonate use and hip fracture epidemiology: ecological proof from the contrary. Clin Interv Aging 5:355–362

Fraser LA, Ioannidis G, Adachi JD, Pickard L, Kaiser SM, Pior J et al (2011) Fragility fractures and the osteoporosis care gap in women: the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Osteoporos Int 22:789–796

Cadarette SM, Katz JN, Brookhart MA, Levin R, Stedman MR, Choudhry NK, Solomon DH (2008) Trends in drug prescribing for osteoporosis after hip fracture, 1995–2004. J Rheumatol 35:319–326

Roerholt C, Eikken P, Abrahamsen B (2009) Initiation of anti-osteoporotic therapy in patients with recent fractures: a nationwide analysis of prescription rates and persistence. Osteoporos Int 20:299–307

Brauer CA, Coa-Perraillon M, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Incidence and mortality of hip fractures in the United States. JAMA 302:1573–1579

Alves SM, Economou T, Oliveira C, Ribeiro NN, Gomez-Barrena PMF (2012) Osteoporotic hip fractures: bisphosphonates sales and observed turning point in trend. A population-based retrospective study. Bone 53:430–436

Watson J, Wise L, Green J (2007) Prescribing of hormone replacement therapy for menopause, tibolone, and bisphosphonates in women in the UK between 1991 and 2005 Eur J. Clin Pharmacol 63:843–849

Reymondier A, Caillet P, Abbas-Chorfa F, Ambrosi V, Jaglal SB, Chapurlat R et al (2013) MENOPOST—calcium and vitamin D supplementation in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment: a descriptive cohort study. Osteoporos Int 24:559–566

Hanley DA, Zhang Q, Meilleur MC, Mavros P, Sen SS (2007) Prescriptions for vitamin D among patients taking antiresorptive agents in Canada. Curr Med Res Opin 23:1473–1480

Bayly JR, Hollands RD, Riordan-Jones SE, Yemm SJ, Brough-Williams I, Thatcher M et al (2006) Prescribed vitamin D and calcium preparations in patients treated with bone remodeling agents in primary care: a report of a pilot study. Curr Med Res Opin 22:131–137

Royal College of Physicians. Falling standards, broken promises. Report of the national audit of falls and bone health in older people 2010. URL: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/sites/default/files/national_report.pdf, assessed 25 Jan 2015

Balasubramanian A, Brookhart MA, Goli V, Critchlow CW (2013) Discontinuation and reinitiation patterns of osteoporosis treatment among commercially insured postmenopausal women. Int J Gen Med 6:839–848

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2008) Technological appraisal (TA)161 Osteoporosis-Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene, strontium ranelate and teriparatide for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women

Kanis JA, Mc Closkey EV, Johansson H, Oden A, Ström O, Borgström F (2010) Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 21:407–413

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2005) Technology appraisal (TA)87. Bisphosphonates (alendronate, etidronate, risedronate), selective oestrogen receptor modulators (raloxifene) and parathyroid hormone (teriparatide) for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women

Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, de Laet CE, Burger H, Seeman E et al (2004) Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone 34:195–202

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui LY, Cauley JA, Ensrud K, Browner WS et al (2003) BMD at multiple sites and risk of fracture of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res 18:1947–1954

Wang L, Shawn Tracy C, Moineddin R, Upshur RE (2013) Osteoporosis prescribing trends in primary care: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 14:1–6

Peeters G, Tett SE, Duncan EL, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ (2014) Osteoporosis medication dispensing for older Australian women from 2002 to 2010: influences of publications, guidelines, marketing activities and policy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 23:1303–1311

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14:1028–1034

Zhang J, Delzell E, Curtis JR, Hooven F, Gehlbach SH, Anderson FA, Saag KG (2013) Use of pharmacologic agents for the primary prevention of osteoporosis among older women with low bone mass. Osteoporos Int 25:317–324

Bessette L, Jean S, Davison KS, Roy S, Ste-Marie LG, Brown JP (2009) Factors influencing the treatment of osteoporosis following fragility fracture. Osteoporos Int 20:1911–1919

Wilk A, Sajjan S, Modi A, Fan C-PS, Mavros P (2014) Post-fracture pharmacotherapy for women with osteoporotic fracture: analysis of a managed care population in the USA. Osteoporos Int 25:2777–2786

Ettinger B, Chidambaran P, Pressman A (2001) Prevalence and determinants of osteoporosis drug prescription among patients with high exposure to glucocorticoid drugs. Am J Manage care 7:597–605

Beaton DE, Dyer S, Jiang D, Sujic R, Slater M, Sale JEM, Bogoch ER (2014) Factors influencing the pharmacological management of osteoporosis after fragility fracture: results from the Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy’s fracture clinic screening program. Osteoporos Int 25:289–296

Duyvendak M, Naunton M, van Roon EN, Brouwers JRBJ (2011) Doctors’ beliefs and knowledge on corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: identifying barriers to improve prevention. J Clin Pharm Ther 36:356–366

Asche C, Nelson R, McAdam-Marx C, Jhaveri M, Ye X (2010) Predictors of oral bisphosphonate prescriptions in post-menopausal women with osteoporosis in a real-world setting in the USA. Osteoporos Int 21:1427–1436

Nayak S, Roberts MS, Chang CC, Greenspan SL (2010) Health beliefs about osteoporosis and osteoporosis screening in older women and men. Health Educ J 69:267–276

Jaglal SB, Carrol J, Hawker G et al (2003) How are family physicians managing osteoporosis? Qualitative study of their experiences and educational needs. Can Fam Physician 49:462–468

Johnson CS, McLeod W, Kennedy L, McLeod K (2008) Osteoporosis health beliefs among younger and older men and women. Health Educ Behave 35:721–733

Sedlak CA, Doheny MO, Estok PJ (2000) Osteoporosis in older men: knowledge and health beliefs. Orthop Nurs 19:38–42

Orwoll E, Ettinger M, Weiss S, Miller P, Kendler D, Adami J, Graham S, Weber K, Lorenc R, Pietschmann P, Vandormael K, Lombardi A (2000) Alendronate for the treatment of osteoporosis in men. N Engl J Med 343:604–610

Lyles K, Colon-Emeric C, Magaziner J, Adachi J, Pieper C, Mautalen C et al (2007) Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med 357:1799–1809

Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, Miller RM, Halbert RJ (2007) Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc 82:1493–1501

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E (2008) FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int 19:385–397

Compston J, Bowring C, Cooper A, Cooper C, Davies C, Francis R, Kanis JA, Marsh D, McCloskey EV, Reid DM, Selby P; National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (2013) Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and older men in the UK: National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) update. Maturitas 75:392–6

Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, Harrington JT, McKinney RE Jr, McLellan A, Mitchell PJ, Silverman S, Singleton R, Siris E (2012) ASBMR Task Force on Secondary Fracture Prevention. Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 27:2039–2046

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C, IOF Fracture Working Group (2013) Capture the Fracture: a Best Practice Framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24:2135–2152

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development [ZonMw; grant number 113101007] and the UK National Osteoporosis Society. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

This work was supported by a grant from the The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development; The Division of Pharmacoepidemiology & Clinical Pharmacology employing FV, CK and TPvS has received unrestricted funding from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association (KNMP), the private-public funded Top Institute Pharma (www.tipharma.nl), includes co-funding from universities, government, and industry), the EU Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), the EU 7th Framework Program (FP7), the Dutch Ministry of Health and industry (including GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer); HGML is a researcher at The WHO Collaborating Centre for Pharmaceutical Policy & Regulation, which receives no direct funding or donations from private parties, including pharma industry. Research funding from public-private partnerships, e.g. IMI, TI Pharma (www.tipharma.nl) is accepted under the condition that no company-specific product or company related study is conducted. The centre has received unrestricted research funding from public sources, e.g. the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW), the Dutch Health Care Insurance Board (CVZ), th EU 7th Framework Program (FP7), the Dutch Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB) and the Dutch Ministry of Health; NCH has received consultancy, lecture fees and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, AMGEN, MSD, Eli Lilly, Servier, Shire, Consilient Healthcare and Internis Pharma; DGS, PMJW, PJME and JWJB report no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Klop, C., Gibson-Smith, D., Elders, P.J.M. et al. Anti-osteoporosis drug prescribing after hip fracture in the UK: 2000–2010. Osteoporos Int 26, 1919–1928 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3098-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-015-3098-x