Abstract

Summary

Treatments to reduce fracture rates in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta are limited. Sclerostin antibody, developed for treating osteoporosis, has not been explored in adults with OI. This study demonstrates that treatment of adult OI mice respond favorably to sclerostin antibody therapy despite retention of the OI-causing defect.

Introduction

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a heritable collagen-related bone dysplasia, characterized by brittle bones with increased fracture risk. Although OI fracture risk is greatest before puberty, adults with OI remain at risk of fracture. Antiresorptive bisphosphonates are commonly used to treat adult OI, but have shown mixed efficacy. New treatments which consistently improve bone mass throughout the skeleton may improve patient outcomes. Neutralizing antibodies to sclerostin (Scl-Ab) are a novel anabolic therapy that have shown efficacy in preclinical studies by stimulating bone formation via the canonical wnt signaling pathway. The purpose of this study was to evaluate Scl-Ab in an adult 6 month old Brtl/+ model of OI that harbors a typical heterozygous OI-causing Gly > Cys substitution on Col1a1.

Methods

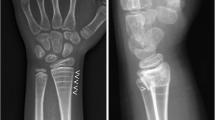

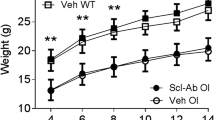

Six-month-old WT and Brtl/+ mice were treated with Scl-Ab (25 mg/kg, 2×/week) or Veh for 5 weeks. OCN and TRACP5b serum assays, dynamic histomorphometry, microCT and mechanical testing were performed.

Results

Adult Brtl/+ mice demonstrated a strong anabolic response to Scl-Ab with increased serum osteocalcin and bone formation rate. This anabolic response led to improved trabecular and cortical bone mass in the femur. Mechanical testing revealed Scl-Ab increased Brtl/+ femoral stiffness and strength.

Conclusion

Scl-Ab was successfully anabolic in an adult Brtl/+ model of OI.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, Marini JC (2011) New perspectives on osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat Rev Endocrinol 7:540–557. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2011.81

Paterson CR, McAllion S, Stellman JL (1984) Osteogenesis imperfecta after the menopause. N Engl J Med 310:1694–1696. doi:10.1056/NEJM198406283102602

Chevrel G, Schott A-M, Fontanges E et al (2006) Effects of oral alendronate on BMD in adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta: a 3-year randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 21:300–306. doi:10.1359/JBMR.051015

Adami S, Gatti D, Colapietro F et al (2003) Intravenous neridronate in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res 18:126–130. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.1.126

Shapiro JR, Thompson CB, Wu Y et al (2010) Bone mineral density and fracture rate in response to intravenous and oral bisphosphonates in adult osteogenesis imperfecta. Calcif Tissue Int 87:120–129. doi:10.1007/s00223-010-9383-y

Bradbury LA, Barlow S, Geoghegan F et al (2012) Risedronate in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta type I: increased bone mineral density and decreased bone turnover, but high fracture rate persists. Osteoporos Int 23:285–294. doi:10.1007/s00198-011-1658-2

Gatti D, Rossini M, Viapiana O et al (2013) Teriparatide treatment in adult patients with osteogenesis imperfecta type I. Calcif Tissue Int 93:448–452. doi:10.1007/s00223-013-9770-2

Orwoll ES, Shapiro J, Veith S et al (2014) Evaluation of teriparatide treatment in adults with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Clin Invest 124:491–498. doi:10.1172/JCI71101

Poole KES, van Bezooijen RL, Loveridge N et al (2005) Sclerostin is a delayed secreted product of osteocytes that inhibits bone formation. FASEB J 19:1842–1844. doi:10.1096/fj.05-4221fje

Li X, Zhang Y, Kang H et al (2005) Sclerostin binds to LRP5/6 and antagonizes canonical Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem 280:19883–19887. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413274200

Leupin O, Piters E, Halleux C et al (2011) Bone overgrowth-associated mutations in the LRP4 gene impair sclerostin facilitator function. J Biol Chem 286:19489–19500. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.190330

Padhi D, Jang G, Stouch B et al (2011) Single-dose, placebo-controlled, randomized study of AMG 785, a sclerostin monoclonal antibody. J Bone Miner Res 26:19–26. doi:10.1002/jbmr.173

Li X, Ominsky MS, Warmington KS et al (2009) Sclerostin antibody treatment increases bone formation, bone mass, and bone strength in a rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 24:578–588. doi:10.1359/jbmr.081206

Ominsky MS, Vlasseros F, Jolette J et al (2010) Two doses of sclerostin antibody in cynomolgus monkeys increases bone formation, bone mineral density, and bone strength. J Bone Miner Res 25:948–959. doi:10.1002/jbmr.14

McClung MR, Grauer A, Boonen S et al (2014) Romosozumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med 370:412–420. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1305224

Forlino A, Porter FD, Lee EJ et al (1999) Use of the Cre/lox recombination system to develop a non-lethal knock-in murine model for osteogenesis imperfecta with an α1(I) G349C substitution. J Biol Chem 274:37923–37931. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.53.37923

Kozloff KM, Carden A, Bergwitz C et al (2004) Brittle IV mouse model for osteogenesis imperfecta IV demonstrates postpubertal adaptations to improve whole bone strength. J Bone Miner Res 19:614–622. doi:10.1359/JBMR.040111

Uveges TE, Collin-Osdoby P, Cabral WA et al (2008) Cellular mechanism of decreased bone in Brtl mouse model of OI: imbalance of decreased osteoblast function and increased osteoclasts and their precursors. J Bone Miner Res 23:1983–1994. doi:10.1359/jbmr.080804

Uveges TE, Kozloff KM, Ty JM et al (2009) Alendronate treatment of the Brtl osteogenesis imperfecta mouse improves femoral geometry and load response before fracture but decreases predicted material properties and has detrimental effects on osteoblasts and bone formation. J Bone Miner Res 24:849–859. doi:10.1359/jbmr.081238

Sinder BP, Eddy MM, Ominsky MS et al (2013) Sclerostin antibody improves skeletal parameters in a Brtl/+ mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res 28:73–80. doi:10.1002/jbmr.1717

Meganck JA, Kozloff KM, Thornton MM et al (2009) Beam hardening artifacts in micro-computed tomography scanning can be reduced by X-ray beam filtration and the resulting images can be used to accurately measure BMD. Bone 45:1104–1116. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2009.07.078

Otsu N (1979) A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern 9:62–66

Hildebrand T, Rüegsegger P (1997) A new method for the model-independent assessment of thickness in three-dimensional images. J Microsc 185:67–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2818.1997.1340694.x

Reeves GM, McCreadie BR, Chen S et al (2007) Quantitative trait loci modulate vertebral morphology and mechanical properties in a population of 18-month-old genetically heterogeneous mice. Bone 40:433–443. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2006.08.018

Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH et al (1987) Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2:595–610. doi:10.1002/jbmr.5650020617

Sinder B, Salemi J, Caird M, et al (2013) Sclerostin antibody increases cortical bone thickness in a rapidly growing Brtl/+ model of OI by inducing bone formation on quiescent or resorbing surfaces. J Bone Miner Res 28 (Suppl 1)

Bivi N, Condon KW, Allen MR et al (2012) Cell autonomous requirement of connexin 43 for osteocyte survival: consequences for endocortical resorption and periosteal bone formation. J Bone Miner Res 27:374–389. doi:10.1002/jbmr.548

Sinder B, White L, Caird M, et al (2012) Sclerostin antibody improves bone mass and mechanical properties in Brtl/+ model of osteogenesis imperfecta when administered during growth. J Bone Miner Res 27 (Suppl 1)

Tian X, Setterberg RB, Li X et al (2010) Treatment with a sclerostin antibody increases cancellous bone formation and bone mass regardless of marrow composition in adult female rats. Bone 47:529–533. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2010.05.032

Kishi T, Hagino H, Kishimoto H, Nagashima H (1998) Bone responses at various skeletal sites to human parathyroid hormone in ovariectomized rats: effects of long-term administration, withdrawal, and readministration. Bone 22:515–522. doi:10.1016/S8756-3282(98)00045-3

Li M, Liang H, Shen Y, Wronski TJ (1999) Parathyroid hormone stimulates cancellous bone formation at skeletal sites regardless of marrow composition in ovariectomized rats. Bone 24:95–100

Chow JW, Fox S, Jagger CJ, Chambers TJ (1998) Role for parathyroid hormone in mechanical responsiveness of rat bone. Am J Physiol 274:E146–E154

Vanlenthe G, Voide R, Boyd S, Muller R (2008) Tissue modulus calculated from beam theory is biased by bone size and geometry: implications for the use of three-point bending tests to determine bone tissue modulus. Bone 43:717–723. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2008.06.008

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bonnie Nolan, Kathy Sweet and Marry Eddy for their contributions. Scl-Ab was provided by Amgen and UCB Pharma. Funding support from NIH to KMK (R01AR062522) is gratefully acknowledged. Study designed and conducted by BPS and KMK. Data collected by BPS, LEW, and JDS. Data analyzed and interpreted by BPS, LEW, JDS, MSO, MSC, JCM, and KMK. The manuscript was written by BPS and KMK and revised and approved by all authors. KMK takes responsibility for the integrity of the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest

Michael S. Ominsky is an employee and stock owner of Amgen Inc. Benjamin P. Sinder, Logan E. White, Joseph D. Salemi, Michelle S. Caird, Joan C. Marini, and Kenneth M. Kozloff declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinder, B.P., White, L.E., Salemi, J.D. et al. Adult Brtl/+ mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta demonstrates anabolic response to sclerostin antibody treatment with increased bone mass and strength. Osteoporos Int 25, 2097–2107 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2737-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2737-y