Abstract

Summary

Most patients are not treated for osteoporosis after their fragility fracture “teachable moment.” Among almost 400 consecutive wrist fracture patients, we determined that better-than-average osteoporosis knowledge (adjusted odds = 2.6) and BMD testing (adjusted odds = 6.5) were significant modifiable facilitators of bisphosphonate treatment while male sex, working outside the home, and depression were major barriers.

Introduction

In the year following fragility fracture, fewer than one quarter of patients are treated for osteoporosis. Although much is known regarding health system and provider barriers and facilitators to osteoporosis treatment, much less is understood about modifiable patient-related factors.

Methods

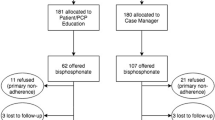

Older patients with wrist fracture not treated for osteoporosis were enrolled in trials that compared a multifaceted intervention with usual care controls. Baseline data included a test of patient osteoporosis knowledge. We then determined baseline factors that independently predicted starting bisphosphonate treatment within 1 year.

Results

Three hundred seventy-four patients were enrolled; mean age 64 years, 78 % women, 90 % white, and 54 % with prior fracture. Within 1 year, 86 of 374 (23 %) patients were treated with bisphosphonates. Patients who were treated had better osteoporosis knowledge at baseline (70 % correct vs 57 % for untreated, p < 0.001) than patients who remained untreated; conversely, untreated patients were more likely to be male, still working, and report depression. In fully adjusted models, osteoporosis knowledge was independently associated with starting bisphosphonates (adjusted OR 2.6, 95 %CI 1.3–5.3). Obtaining a BMD test (aOR 6.5, 95 %CI 3.4–12.2) and abnormal BMD results (aOR 34.5, 95 %CI 16.8–70.9) were strongly associated with starting treatment.

Conclusions

The most important modifiable facilitators of osteoporosis treatment in patients with fracture were knowledge and BMD testing. Specifically targeting these two patient-level factors should improve post-fracture treatment rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Majumdar SR (2011) A T-2 translational research perspective on interventions to improve post-fracture osteoporosis care. Osteoporos Int 22(suppl 3):S471–S476

Little EA, Eccles MP (2010) A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to improve post-fracture investigation and management of patients at risk of osteoporosis. Implement Sci 5:80–88

Sujic R, Gignac MA, Cockerill R, Beaton DE (2011) A review of patient centered post-fracture interventions in the context of theories of health behavior change. Osteoporos Int 22:2213–2224

MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V et al (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med 148:197–213

Majumdar SR, Rowe BH, Folk D, Johnson JA, Holroyd BH et al (2004) A controlled trial to increase detection and treatment of osteoporosis in older patients with a wrist fracture. Ann Intern Med 141:366–373

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, McAlister FA, Bellerose D, Russell AS et al (2008) Multifaceted intervention to improve osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment in patients with recent wrist fracture: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 178:569–575

Majumdar SR, Johnson JA, Bellerose D, McAlister FA, Russell AS et al (2011) Nurse case-manager vs multifaceted intervention to improve quality of osteoporosis care after wrist fracture: randomized controlled pilot study. Osteoporos Int 22:223–230

Marsh D, Akesson K, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Boonen S et al (2011) Coordinator-based systems for secondary prevention in fragility fracture patients. Osteoporos Int 22:2051–2065

McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM (2003) Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res 18:156–170

Lawson PJ, Flocke SA (2009) Teachable moments for health behavior change: a concept analysis. Patient Educ Couns 76:25–30

Cohen DJ, Clark EC, Lawson PJ, Casucci BA, Flocke SA (2011) Identifying teachable moments for health behavior counseling in primary care. Patient Educ Couns 85:e8–e15

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-item short form health survey (SF-12): construction of scales and preliminary test of reliability and validity. Med Care 34:220–226

Johnson JA, Pickard AS (2000) Comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-12 in a general population survey in Alberta, Canada. Med Care 38:115–121

Lydick E, Zimmerman SI, Yawn B, Love B, Kleerekoper M et al (1997) Development and validation of a discriminative quality of life questionnaire for osteoporosis (the OPTQoL). J Bone Miner Res 12:456–463

Ailinger RL, Harper DC, Lasus HA (1998) Development of the facts on osteoporosis quiz. Orthop Nurs 17:66–73

Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS (2002) Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:877–883

Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW (2009) Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 20:488–495

Phillipov G, Philips PJ, Leach G, Taylor AW (1998) Public perceptions and self reported prevalence of osteoporosis in South Australia. Osteoporos Int 8:552–556

Tannebaum C, Mayo N, Ducharme F (2005) Older women’s health priorities and perceptions: results of the WOW health survey. CMAJ 173:153–159

Cline RR, Farley JF, Hansen RA, Schommer JC (2005) Osteoporosis beliefs and antiresorptive medication use. Maturitas 50:196–208

Yood RA, Mazor KM, Andrade SE, Emani S, Chan W, Kahler KH (2008) Patient decision to initiate therapy for osteoporosis: the influence of knowledge and beliefs. J Gen Intern Med 23:1815–1821

Feldstein AC, Schneider J, Smith DH, Vollmer WM, Rix M et al (2008) Harnessing stakeholder perspectives to improve the care of osteoporosis after a fracture. Osteoporos Int 19:1527–1540

Campbell MK, Torgerson DJ, Thomas RE, McClure JD, Reid DM (1998) Direct disclosure of bone density results to patients: effect on knowledge of osteoporosis risk and anxiety level. Osteoporos Int 8:584–590

Solomon DH, Levin E, Helfgott SM (2000) Patterns of medication use before and after bone densitometry: factors associated with appropriate treatment. J Rheumatol 27:1496–1500

Cadarette SM, Gignac M, Jaglal SB, Beaton DE, Hawker GA (2007) Access to osteoporosis treatment is critically linked to access to dual energy x-ray absorptiometry testing. Med Care 45:896–901

Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M, Yardley L, Pope C et al (2005) Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies on medicine taking. Soc Sci Med 61:133–155

Grenard JL, Munjas BA, Adams JL, Suttorp M, Maglione M et al (2011) Depression and medication adherence in the treatment of chronic disease: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 26:1175–1182

Sedlak CA, Doheny MO, Estok PJ (2000) Osteoporosis in older men: knowledge and health beliefs. Orthop Nurs 19:38–42

Morrish DW, Beaupre LA, Bell NR, Cinats JG, Hanley DA et al (2009) Facilitated bone mineral density testing versus hospital-based case management to improve osteoporosis treatment for hip fracture patients: additional results from a randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum 61:209–215

Conflicts of interest

SR Majumdar, FA McAlister, JA Johnson, DL Weir, D Bellerose, DA Hanley, AS Russell, and BH Rowe declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to this study. The corresponding author (SRM) had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were involved in conception and design and analysis and interpretation and provided critical revision to manuscript drafts. DL also undertook statistical analyses. SRM also wrote the first draft, obtained funding, and supervised the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported by

Peer-reviewed operating grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. SRM, FAM, and JAJ hold salary awards from Alberta Innovates—Health Solutions; SRM holds the Endowed Chair in Patient Health Management from the Faculties of Medicine and Dentistry and Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta; FAM holds the University of Alberta Chair in Cardiovascular Outcomes Research; and JAJ and BHR hold CIHR-Canada Research Chairs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Majumdar, S.R., McAlister, F.A., Johnson, J.A. et al. Critical impact of patient knowledge and bone density testing on starting osteoporosis treatment after fragility fracture: secondary analyses from two controlled trials. Osteoporos Int 25, 2173–2179 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2728-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-014-2728-z