Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD) affects many women and participation in elite sport and high-impact exercise has been reported as a potential risk. However, few studies have investigated the effects of exercising at recreational levels on PFD. Our aim was to investigate levels of PFD in women exercising at, or above, UK guidelines for health and compare them with levels in non-exercisers.

Method

Data on levels of PFD and potential risk factors (age, hormonal status, body mass index, constipation, parity, forceps delivery, and recreational exercise) were collected using a cross-sectional survey distributed via social media. The International Consultation Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) Urinary Incontinence Short Form was used to estimate prevalence of urinary incontinence (UI). Selected questions from the ICIQ vaginal symptom and bowel symptom questionnaires were used to estimate prevalence of anal incontinence (AI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Logistic regression analysis was used to compare exercisers and non-exercisers after adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

We recruited 1,598 adult women (1,141 exercisers and 457 non-exercisers). The majority were parous. High prevalence of UI (70%), AI (52%) and POP (18%) was reported. No significant association was found between recreational exercise and PFD despite adjustment for confounders, or further investigation regarding exercise involving impact, although some increased reporting of AI was seen in those exercising for over 10 hours per week.

Conclusion

High levels of all PFD were reported but no significant association was found between recreational exercise and symptoms. However, data suggest that women modify their exercise regimes as required. Few symptomatic women sought professional help.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), which includes urinary incontinence, anal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) [1], causes embarrassment and distress, limits many aspects of life [2] and affects many women [3]. It is accepted that childbirth, obesity and aging are risk factors for PFD [4] but recent evidence suggests that the prevalence of urinary incontinence in young, nulliparous athletic women is 2.77 times higher than in their sedentary counterparts [5]. Other reports suggest that high-impact activities, e.g. cheer leading, may be linked with increased levels of anal incontinence (AI) [6]. However, regular participation in sport and exercise confers multiple health benefits [7, 8]. Current UK recommendations are that adults should exercise at moderate levels or above for a minimum of 150 min each week, over three sessions [9]. Urinary incontinence (UI) can be a barrier to exercise [10] and concern regarding potential risks to the pelvic floor, as reported in elite athletes, may cause health professionals and women to question the safety of engaging in sport and exercise, for fear of aggravating symptoms or increasing the risk of developing PFD. Although studies have investigated whether the risk of PFD is higher in elite athletes than in sedentary individuals [11] and in younger women [6, 12], only a few have reported levels within a broad range of recreational athletes [13, 14]. Therefore, the objectives of this study were:

-

1.

To investigate the levels of PFD reported by women who exercise at, or above UK guidelines for healthy living and in those who are more sedentary.

-

2.

To investigate any association between PFD and taking part in sport at a recreational level.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional survey specifically designed to investigate levels of UI, AI and POP in a convenience sample of adult women, reported using Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [15]. The study steering group, comprising the authors and a PPI member, designed the survey and developed it on Jisc Online surveys. The survey contained 37 questions divided into sections so that participants could bypass questions that did not apply to them. It was initially piloted with 31 participants recruited from administrative and academic staff from the School of Health Sciences, University of Nottingham, and a local physiotherapy clinic, to identify any issues with the language or question format. Minor signposting problems and issues with terminology identified were resolved.

Sample size

In order to investigate a predicted potential significant difference of 10% in prevalence of PFD between recreational exercisers [14] and the general female population [16], with significance level set to 0.05 and 80% power, we aimed to recruit a minimum of 800 participants: 500 exercisers and 300 non-exercisers.

Participants and recruitment

Adult women were invited to take part via advertisements, which were widely distributed on social media networks (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and LinkedIn) and using snowball methodology (asking people to share the information with others). Posters were also distributed to sports clubs, workplaces and physiotherapy clinics for display on websites and notice boards. QR codes linked directly to the survey. Advertisements highlighted that ALL women were invited to take part: both those who did and those who did not exercise and both those with and those without any pelvic floor symptoms. Data collection took place between 6 May and 31 July 2022.

Outcome measures

To determine the prevalence of UI, AI and POP (as defined by the International Urogynaecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report) [1], we collected data using patient-reported outcome measures. We used the International Consultation Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ) Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI-SF) [17] in its entirety, and specific questions of interest from ICIQ bowel symptom [18] and ISIQ vaginal symptom questionnaires [19]. Inclusion of all three questionnaires in full would have resulted in a prohibitively time-consuming survey, likely to deter participation.

Those who reported “never” in response to the question “How often do you leak urine?” were classified as continent of urine, and severity was defined by the ICIQ-UI-SF severity score [20]. UI was further subdivided into stress UI (SUI), urgency UI (UUI) and mixed UI (MUI) based on the answers to “When does urine leak?” Anal continence was identified in those who answered, “always” to the question “Are you able to control leakage of stool or flatus (wind) from your back passage?” Responding “never” to the question “Are you aware of a lump or bulge coming down in your vagina?” was taken to indicate the absence of POP. Awareness of a lump or bulge in the vagina has been associated with the presence of a grade 2 POP, although this may underestimate the true prevalence of this dysfunction [21]. Age, menopausal status, body mass index (BMI), constipation (defined as regularly having to strain to open bowels), parity and type of delivery were considered potential risk factors for PFD and possible confounders.

Recreational athletes were defined to be those who met and exceeded the UK Chief Medical Officer’s guidelines for healthy living of 150 min a week [9]. This was further subdivided into high-impact (sports involving both feet leaving the ground at the same time, e.g., running, high impact gym or trampolining) and low-impact (one foot always in contact with the ground or body weight supported, e.g. walking, cycling, kayaking) or both.

Additionally, participants were asked if they had sought professional help for PFD, and if they regularly performed pelvic floor exercises. The final open question gave participants an opportunity to record comments or additional information regarding previous answers.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in SPSS statistical software version 28 (IBM, Chicago, USA). Demographic data were reported using frequencies with percentages or means with standard deviations (SD). Prevalence was reported as frequency and percentage, and Pearson’s Chi-squared test was used to investigate any differences in prevalence of PFD between non-exercisers and exercisers. Missing data were reported. Risk factors for PFD were estimated by logistic binomial regression analysis, reported as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), with the significance level set to 0.05.

Results

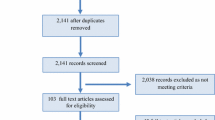

Visits to the survey site were recorded to be 4,985: 3,185 exiting after the first page (survey information). A few individuals then exited from subsequent pages but most who progressed to consent then completed the survey (Fig. 1). Individual IP addresses were not collected due to the anonymising process so it is not possible to calculate participation rate; each visit recorded could represent duplicate visits by the same participant or unique visits.

In total, 1,600 participants consented to take part and submitted data. Two were excluded: one self-identified as a man, noting that they were male at birth, but wished to underline the need for a similar survey for men; and one did not provide key data regarding birth history, menopausal status and exercise history. Data submitted by the remaining 1,598 participants was analysed: of these 1,141 (71%) reported exercise levels above UK guidelines of more than 150 min per week and 457 (29%) did not exercise or were below this level. Most exercisers (921, 81%) reported doing so for over 5 years and 1,041 (91%) exercised more than three times per week, in line with guidelines. Owing to an initial system issue, 8 participants were able to bypass some questions regarding bowel and vaginal symptoms, which is noted within the results tables.

Demographics

A majority, 1,359 (85%), of participants were UK based and 144 (9%) were based in the USA, Canada and Australia. All age groups were represented, most, 1,064 (67%), under 50, and 954 (60%) self-identified as being pre-menopausal. The majority, 1,347 (84%), were educated to degree level or above (used to estimate health literacy levels). Average participant BMI was 25.4 kg/m2 (SD 5.02, range 15.0–51.6); slightly above normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2. Most, 1,105 (69%), were parous, over half of these reporting two births and 13% experienced a forceps delivery (Table 1).

Main outcomes

Prevalence

Bladder: 1,120 (70%, 95% CI 68–72%) of participants reported UI: 592 (37%) SUI, 180 (11%) UUI and 294 (18%) MUI.

Bowel: faecal urgency was reported by 450 (28%, 95% CI 26—30%) participants, 769 (48%, 95% CI 46–51%) reported difficulty controlling flatus and/or stool (AI) and 276 (17%, 95% CI 16—19%) noted marking of underwear by stool.

Prolapse: 293 (18%, 95% CI 17–20%) women noted the sensation of bulging in the vagina.

Associations

There were no significant between group differences regarding exercisers and non-exercisers in levels of UI (p=0.352), AI (p=0.182) or POP (p=0.152). Exercisers were less likely to report constipation: 17% compared with 22% of non-exercisers (p=0.019; Table 2) .

After regression analysis using logistic binomial regression to account for other risk factors (age, reduced oestrogen, BMI, constipation, parity and forceps delivery) with non-exercisers (<2.5 h/week) as the reference group, no significant association was found between recreational exercise and PFD.

Risk factors associated with UI included aging, BMI, constipation and parity. AI was associated with age, constipation and forceps delivery. POP was associated with hormonal status, constipation and increasing parity (Table 3).

Subdivision of exercise levels based on hours/week: (2.5–6 h, 6–10 h and > 10 h) showed no significant differences regarding prevalence of UI. Women who exercised >10 h/week reported fewer incidences of POP (OR 0.70, CI 95% 0.42–1.19), but this was not significant (p=0.190). There was, however, increased reporting of AI by those exercising >10 h/week: adjusted OR of 1.48 (CI 95%, 1.04–2.10 (Table 4).

Further investigation to account for potential effects of exercise involving impact only as opposed to non-impact sport revealed no significant differences in levels of PFD (Table 5).

Pelvic floor exercises and treatments

Pelvic floor exercises were performed regularly by only 646 (40%) participants.

Of those reporting any pelvic floor dysfunction, only 450 out of 1,319 (34%) had sought professional help. Those with symptoms were no more or less likely to exercise their pelvic floors.

Responses to open question

In the final section, 537 participants made comments. These are reported in detail elsewhere [22] but we report, in brief, key illustrative quotations regarding impact of symptoms on access to sport and treatments to manage symptoms.

Pelvic floor symptoms impacting access to sport

Often participants commented that their pelvic floor symptoms were the reason why they could no longer take part in sport and exercise:

“I would love to exercise to lose weight, but it is impossible with these bladder issues … it's so frustrating”

“…my exercise intensity and frequency have changed since having children due to leakage/prolapse symptoms. Before kids my exercise intensity was high and 6 days/week. Now, I don’t engage in high intensity exercise anymore….”

Many commented on the negative effects of this, ranging from ensuring that their bladder had been emptied before leaving the house:

“I feel like I should always empty my bladder before I leave the house, gym, work etc. to avoid a panic when I need to urinate.”

to great distress:

“It's impacted my life; I can't run anymore …. No one gives a damn because it's only women.”

Treatment

Some commented on treatments they had attempted to seek or been offered, and many suggested that pelvic floor muscle exercises did help:

“Doing daily regular sustained pelvic floor exercises has greatly improved my symptoms”

whereas others found that taking part in sport had helped:

“I started to include weight training …. and feel that has helped my pelvic floor enormously.”

Discussion

The objectives of this survey were to determine the levels of PFD in women who exercised at or above recommended guidelines for healthy living and in those who did not and to identify any correlation between exercising recreationally and the incidence of PFD, as previously noted in literature regarding elite athletes [11, 12, 23, 24].

All levels of PFD reported were high compared with other studies: UI was reported by 40% of women in a 2015 UK survey [16] compared with 70% of our participants, and AI was reported by only 14% of women in a US epidemiological survey [25] compared with 48% in this survey. However, a recent study investigating the long-term effects of sphincter injuries at birth on AI reported 60% prevalence of AI in the control group (those without sphincter injury) [26] and this level was similar to that found in a group of young, nulliparous women [12]. Levels of POP again appear to be greater than that reported in the US epidemiological study [25] but in another recent internet-based survey, 14% of participants reported POP [13] compared with 18% of our respondents. It is likely that there will be some selection bias in an internet survey as women with an interest are more likely to take part, despite advertisements aiming to recruit ALL women. However, it may be that as pelvic health symptoms are increasingly being discussed more openly in the media women are becoming more confident to share information regarding these symptoms.

We found no significant associations between taking part in recreational sport and exercise and PFD other than a small increase in the number of women reporting AI when exercising for more than 10 h/week. However, this should be interpreted with caution given the low numbers of women exercising at higher levels in this survey. It is important to note that many previous studies reporting increased levels of PFD in athletes have investigated the elite population [11], whereas other investigations that have noted significantly higher levels of UI included only young nulliparous women, without the increased extra risks associated with parity and/or assisted delivery in their sedentary cohort [12]. Athletes in the latter study reported training on average for 19 h/week, whereas the majority of our exercisers were exercising for less than 10 h/week and a positive association has been reported between volume of physical activity and the frequency of UI [27]. However, a previous study also found no significant correlation between UI or POP and exercise, and the only significant correlation reported was between AI and sport [28].

The demands of elite level competition dictate that reducing training levels or modifying load is rarely an option unless there is illness or injury. It is therefore likely that elite athletes, many of whom have never mentioned their symptoms to anyone [29], would not alter their sport or training levels as a result of PFD. In the case of the recreational athletes in our survey, however, comments suggested that women often modified their sports to include lower impact activities or reduced the level of exercise they took part in altogether. This, combined with the lower volume of exercise performed by most of our exercisers, may explain the differences in the results. However, it should also be noted that as the majority of exercisers in our survey have been doing so for over 5 years there is little in this study to suggest that recreational sport at these levels is a specific risk to the pelvic floor.

Finally, the majority of those who reported PFD here had not sought professional help, despite comments suggesting that PFD caused distress. This is recognised and has previously been reported in other studies on both athletes [29] and the general population [16].

A major strength of internet-based surveys is the ability to recruit large numbers of participants from a spread of geographical locations. Moreover, although self-reporting of symptoms may be less accurate than using objective measures such as pad tests to detect incontinence or vaginal examination to diagnose POP, this is mitigated by the use of validated questionnaires to predict symptoms.

There are, however, associated limitations, not least of which is the possibility of selection bias, as those affected by the criteria being investigated are most likely to take part, which may increase prevalence levels. In addition, although advertisements asked ALL women to participate, the only inclusion criteria were to be adult and female; this could mean that some were pregnant or possessed disabilities that could have an impact on their pelvic floor function. Further, although we aimed to recruit a diverse population, the majority of participants were educated to degree level or above. It is then even more surprising that most symptomatic participants had never sought professional help.

Conclusion

Overall levels of PFD within this survey are high but there was no association between recreational exercise and the rates of PFD reported. Further longitudinal studies may help to investigate any long-term risks of recreational exercise to pelvic health. However, based on the results of this survey and the multiple health benefits associated with taking part in regular sport and exercise, women and health professionals should be cautious when extrapolating the risks to the pelvic floor associated with elite sport to recreational exercisers.

References

Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:5–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9.

Nilsson M, Lalos A, Lalos O. The impact of female urinary incontinence and urgency on quality of life and partner relationship. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(8):976–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20709.

Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300(11):1311–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.300.11.1311.

Danforth KN, Townsend MK, Lifford K, Curhan GC, Resnick NM, Grodstein F. Risk factors for urinary incontinence among middle-aged women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(2):339–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.051.

Teixeira RV, Colla C, Sbruzzi G, Mallmann A, Paiva LL. Prevalence of urinary incontinence in female athletes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(12):1717–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3651-1.

Vitton V, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Brardjanian S, Caballe I, Bouvier M, Grimaud JC. Impact of high-level sport practice on anal incontinence in a healthy young female population. J Womens Health. 2011;20(5):757–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2454.

Lewis SF, Hennekens CH. Regular physical activity: forgotten benefits. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):137–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.07.016.

Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;174(6):801–9. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051351.

Department of Health and Social Care. Physical activity guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ Report. London: Department of Health and Social Care; 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Nygaard I, Girts T, Fultz NH, Kinchen K, Pohl G, Sternfeld B. Is urinary incontinence a barrier to exercise in women? Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(2):307–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000168455.39156.0f.

Carvalhais A, Natal Jorge R, Bø K. Performing high-level sport is strongly associated with urinary incontinence in elite athletes: a comparative study of 372 elite female athletes and 372 controls. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(24):1586–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-097587.

Almeida MBA, Barra AA, Saltiel F, Silva-Filho AL, Fonseca AMRM, Figueiredo EM. Urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor dysfunctions in female athletes in Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;26(9):1109–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12546.

Forner LB, Beckman EM, Smith MD. Symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse in women who lift heavy weights for exercise: a cross-sectional survey. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(8):1551–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04531-x.

McKenzie S, Watson T, Thompson J, Briffa K. Stress urinary incontinence is highly prevalent in recreationally active women attending gyms or exercise classes. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(8):1175–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2954-3.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD.

Cooper J, Annappa M, Quigley A, Dracocardos D, Bondili A, Mallen C. Prevalence of female urinary incontinence and its impact on quality of life in a cluster population in the United Kingdom (UK): a community survey. Primary Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(4):377–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1463423614000371.

Avery K, Donovan J, Peters TJ, Shaw C, Gotoh M, Abrams P. ICIQ: a brief and robust measure for evaluating the symptoms and impact of urinary incontinence. Neurol Urodyn. 2004;23:322–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20041.

Cotterill N, Norton C, Avery KN, Abrams P, Donovan JL. Psychometric evaluation of a new patient-completed questionnaire for evaluating anal incontinence symptoms and impact on quality of life: the ICIQ-B. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(10):1235–50. https://doi.org/10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182272128.

Price N, Jackson S, Avery K, Brookes S, Abrams P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the ICIQ Vaginal Symptoms Questionnaire: the ICIQ-VS. BJOG. 2006;113(6):700–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00938.x.

Klovning A, Avery K, Sandvik H, Hunskaar S. Comparison of two questionnaires for assessing the severity of urinary incontinence: The ICIQ-UI SF versus the incontinence severity index. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009;28(5):411–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.20674.

Barber MD, Neubauer NL, Klein-Olarte V. Can we screen for pelvic organ prolapse without a physical examination in epidemiologic studies? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(4):942–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2006.02.050.

Campbell KG, Batt ME, Drummond A. Perspectives of women living and exercising with pelvic floor disorders: findings from the ‘PREDICT’ survey. J Pelvic Obstet Gynaecol Physiother. (In press).

Araujo MP, Parmigiano TR, Della Negra LG, et al. Evaluation of athletes’ pelvic floor: is there a relation with urinary incontinence? Rev Bras Med Esp. 2015;21(6):442–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/1517-869220152106140065.

Skaug KL, Engh ME, Frawley H, Bø K. Urinary and anal incontinence among female gymnasts and cheerleaders—bother and associated factors. A cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J. 2022;33(4):955–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-021-04696-z.

Gabra MG, Tessier KM, Fok CS, Nakib N, Oestreich MC, Fischer J. Pelvic organ prolapse and anal incontinence in women: screening with a validated epidemiology survey. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2022;306(3):779–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06510-7.

Everist R, Burrell M, Parkin K, Patton V, Karantanis E. The long-term prevalence of anal incontinence in women with and without obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Continence. 2023;5:100571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cont.2022.100571.

Alves JO, Luz STD, Brandao S, Da Luz CM, Jorge RN, Da Roza T. Urinary incontinence in physically active young women: prevalence and related factors. Int J Sports Med. 2017;38(12):937–41. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-115736.

Carvalho C, da Silva Serrão PRM, Beleza ACS, Driusso P. Pelvic floor dysfunctions in female cheerleaders: a cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31(5):999–1006. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04074-w.

Carls C. The prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in high school and college-age female athletes in the midwest: implications for education and prevention. Urol Nurs. 2007;27(1):21–4, 39.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all who took part in both the pilot and the final survey for taking the time to submit their data and comments. Thanks also to the PPI member of our steering group, for her insight and contribution to the design and implementation of the survey. We would also like to thank Andrea Venn for her help and support with conducting and interpreting the statistical analysis. Finally, we would like to thank all those who took the time to advertise and share the survey on their websites, notice boards and social media platforms.

Funding

This study was funded by the NIHR as part of an ICA post-doctoral bridging award for K.G.C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the design of the survey, protocol and authorship of the article. K.G. Campbell: protocol development, data collection, management and analysis, manuscript writing; M.E. Batt: protocol development, data collection, management, manuscript writing; A. Drummond: protocol development, data collection, management, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Nottingham, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee FMHS 501–0322. All participants gave electronic consent before progressing to data collection. Data were anonymised at source and no individual IP addresses were retained.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Data sharing

A summary of the data set generated and analysed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Public and patient involvement

A patient representative, who has experienced pelvic floor dysfunction and its impact on her sport, was involved as a member of the study steering group from its inception and took an equal part in all aspects of design of the survey, study protocol and decisions regarding advertising and analysis. She will continue to be involved as a member of the steering group to decide on potential ways to disseminate the results to the public going forward. Further, local women were recruited to pilot initial versions of the survey to identify any issues with wording and content. The final version was modified based on their feedback.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Campbell, K.G., Batt, M.E. & Drummond, A. Prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction in recreational athletes: a cross-sectional survey. Int Urogynecol J 34, 2429–2437 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05548-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-023-05548-8