Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

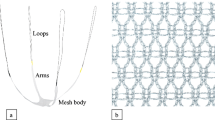

The use of new lightweight meshes in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery may reduce complications related to mesh retraction (chronic pain, dyspareunia, and mesh exposure). The aim of this study was to investigate changes in the area and position of Uphold Lite™ mesh 6 weeks and 12 months after anterior and/or apical prolapse repair.

Methods

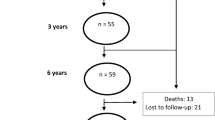

This observational prospective multicenter study included patients who had undergone transvaginal surgery for symptomatic POP-Q stage ≥ II anterior and/or apical compartment prolapse with placement of Uphold Lite mesh. The dimensions and position of the mesh were evaluated at 6 weeks and 12 months by ultrasonography. Correlations between ultrasonographic mesh characteristics and POP recurrence were analyzed.

Results

Fifty evaluable women with an average age of 66.8 years were included. No statistically significant difference in mesh area was found between week 6 and month 12 postoperatively, either at rest (1746.92 vs. 1574.48 mm2; p = 0.15) or on Valsalva (1568.81 vs. 1542.98 mm2; p = 0.65). The ROC-AUC of the distance between the mesh and the bladder neck (M-BN) at 6 weeks for predicting cystocele recurrence at 12 months was 0.764 (95% CI 0.573–0.955) at rest and 0.724 (95% CI 0.533–0.916) on Valsalva. An M-BN distance > 12.5 mm could predict cystocele recurrence at month 12 with a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 69%.

Conclusions

Ultrasonographic measurements of the Uphold Lite™ mesh appear to remain stable between 6 weeks and 12 months postoperatively. M-BN distance correlates with cystocele recurrence. These results appear to confirm the value of ultrasound in mesh evaluation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vollebregt A, Fischer K, Gietelink D, van der Vaart CH. Primary surgical repair of anterior vaginal prolapse: a randomised trial comparing anatomical and functional outcome between anterior colporrhaphy and trocar-guided transobturator anterior mesh. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;118:1518–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03082.x.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD004014. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub6.

Diez-Itza I, Aizpitarte I, Becerro A. Risk factors for the recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse after vaginal surgery: a review at 5 years after surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1317–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-007-0321-0.

US FDA: Urogynecologic Surgical Mesh Implants. http://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants. Published April 16, 2019.

SCENIHR: The safety of surgical meshes used in urogynecological surgery. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/emerging/docs/scenihr_o_049.pdf.

Birch C, Fynes MM. The role of synthetic and biological prostheses in reconstructive pelvic floor surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:527–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001703-200210000-00015.

Deval B, Haab F. What’s new in prolapse surgery? Curr Opin Urol. 2003;13:315–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00042307-200307000-00008.

Debodinance P, Berrocal J, Clavé H, et al. Changing attitudes on the surgical treatment of urogenital prolapse: birth of the tension-free vaginal mesh. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2004;33:577–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0368-2315(04)96598-2.

Tunn R, Picot A, Marschke J, Gauruder-Burmester A. Sonomorphological evaluation of polypropylene mesh implants after vaginal mesh repair in women with cystocele or rectocele. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;29:449–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.3962.

Schuettoff S, Beyersdorff D, Gauruder-Burmester A, Tunn R. Visibility of the polypropylene tape after tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure in women with stress urinary incontinence: comparison of introital ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in vitro and in vivo. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2006;27:687–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.2781.

Velemir L, Amblard J, Fatton B, et al. Transvaginal mesh repair of anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse: a clinical and ultrasonographic study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35:474–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.7485.

Liang R, Knight K, Abramowitch S, Moalli PA. Exploring the basic science of prolapse meshes. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0000000000000313.

Patel H, Ostergard DR, Sternschuss G. Polypropylene mesh and the host response. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:669–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-012-1718-y.

Altman D, Mikkola TS, Bek KM, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse repair using the uphold™ vaginal support system: a 1-year multicenter study. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:1337–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-2973-0.

Allegre L, Debodinance P, Demattei C, et al. Clinical evaluation of the uphold LITE mesh for the surgical treatment of anterior and apical prolapse: a prospective, multicentre trial. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:2242–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/nau.24125.

Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10–7.

Šimundić A-M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. EJIFCC. 2009;19:203–11.

Dietz HP, Erdmann M, Shek KL. Mesh contraction: myth or reality? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:173.e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.058.

Svabík K, Martan A, Masata J, et al. Ultrasound appearances after mesh implantation--evidence of mesh contraction or folding? Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:529–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-010-1308-9.

Harsløf S, Zinther N, Harsløf T, et al. Mesh shrinkage depends on mesh properties and anchoring device: an experimental long-term study in sheep. Hernia J Hernias Abdom Wall Surg. 2017;21:107–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-016-1528-0.

Ostergard DR. Polypropylene vaginal mesh grafts in gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:962–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f39b20.

Rogowski A, Bienkowski P, Tosiak A, et al. Mesh retraction correlates with vaginal pain and overactive bladder symptoms after anterior vaginal mesh repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:2087–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-013-2131-x.

Lo T-S, Pue LB, Tan YL, et al. Anterior-apical single-incision mesh surgery (uphold): 1-year outcomes on lower urinary tract symptoms, anatomy and ultrasonography. Int Urogynecol J. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3691-6.

Wong V, Guzman Rojas R, Shek KL, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: how low does the mesh go? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol Off J Int Soc Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49:404–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.15882.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BESPIM department of Nîmes University Hospital for statistical analysis and data management.

We thank all the investigators, including those not listed as authors: Philippe Debodinance, Christophe Courtieu, Melanie Cayrac, Xavier Fritel, Maxime Marcelli, Aubert Agostini, and François Monneins.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Boston Scientific, but the company had no influence over the execution of the study, data analysis, or interpretation of the data and was not involved in drafting the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L Allègre: Data collection, Data analysis, Manuscript writing/editing.

G Callewaert: Dataanalysis, Manuscript writing/editing.

C Coudray: Data analysis, Manuscript writing.

C Demattei: Data analysis.

L Panel: Data collection.

C Carlier-Guerin: Data collection.

V Letouzey: Protocol development.

R de Tayrac: Protocol development, Data collection, Manuscript editing.

B Fatton: Protocol development, Data collection, Manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. de Tayrac and B. Fatton are consultant for Boston Scientific.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Allègre, L., Callewaert, G., Coudray, C. et al. Prospective ultrasonographic follow-up of transvaginal lightweight meshes: a 1-year multicenter study. Int Urogynecol J 32, 1505–1512 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04483-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04483-2