Abstract

Satellite laser ranging (SLR) constitutes a fundamental space geodetic technique providing global geodetic parameters, such as geocenter coordinates, Earth rotation parameters, and low-degree gravity field coefficients. The tropospheric delay correction is one of the crucial corrections that have to be taken into account when processing SLR data. Current conventional models of the troposphere delays assume a full symmetry of the atmosphere above SLR stations. Neglecting horizontal gradients in SLR solutions introduces a systematic error in SLR products, especially for the observations at low elevation angles, and leads to a deterioration of the consistency between SLR and other space geodetic techniques, such as global navigational satellite systems and very-long-baseline interferometry. We derive new mapping function coefficients, as well as first- and second-order horizontal gradients, all of which are based on numerical weather models, in order to properly consider the azimuthal asymmetry in SLR solutions. We test the enhanced mapping function and horizontal gradients on the solutions based on 11 years of SLR observations to LAGEOS-1/2 satellites and 1 year of SLR observations to Sentinel-3A. The consideration of azimuthal asymmetry of the atmosphere above the SLR stations has a systematic effect on SLR-derived products, such as station and geocenter coordinates and pole coordinates. Horizontal gradients in SLR solutions improve the consistency between SLR-derived pole coordinates and the combined IERS-C04 series by means of reducing the offset for the X and Y pole coordinates by 20 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\). The second-order horizontal gradients are negligible in SLR solutions; thus, including first-order gradients is sufficient for SLR solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The atmospheric refractivity is one of the most important factors of observation corrections in space geodetic techniques. The currently used troposphere delay model in SLR observations comprises the estimation of the tropospheric delay \(d_\mathrm{atm}\) as a product of the delay in the zenith direction \(d^{z}_\mathrm{atm}\) based on the model derived by Mendes and Pavlis (2004) and the mapping function commonly used for laser data (Mendes et al. 2002), m(e). A similar functional model consisting of the zenith delay and the mapping function with different coefficients is widely used for processing global navigational satellite system (GNSS) data (e.g., Böhm and Schuh 2007; Böhm et al. 2015) and very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI) data (e.g., MacMillan and Ma 1997; Niell 2000; Rocken et al. 2001; Nilsson et al. 2017; Heinkelmann et al. 2018; Landskron and Böhm 2018a, b). However, only in SLR solutions the troposphere delay model consists of zenith delay and the mapping function disregarding the actual state of the atmosphere at the site due to assuming full symmetry of the atmosphere above the station.

Recent studies of atmospheric refractivity show that the best results are obtained when considering the impact of the atmosphere azimuthal asymmetry (e.g., Böhm et al. 2010; Landskron and Böhm 2018b). Due to different local conditions and the variability of atmospheric conditions, the best results are obtained when utilizing higher-order horizontal gradients (Balidakis et al. 2018; Landskron and Böhm 2018a; Masoumi et al. 2017).

The SLR technique is the only one space geodetic technique which employs optical laser measurements and thus has a different sensitivity to the atmospheric refractivity when compared to microwave GNSS or VLBI observations. The impact of the wet delay on the SLR observations is about 70 times smaller than on GNSS observations, whereas the impact of the hydrostatic delay has a similar order for SLR and microwave data. The hydrostatic delay is typically well measured and modeled; thus, the troposphere delay modeling in SLR solutions does not require estimation of any additional parameters. The SLR delay modeling is based on meteorological measurements simultaneously performed with SLR observations that are introduced to models proposed by Mendes and Pavlis (2004) with FCULa.

Hulley and Pavlis (2007) proposed a method of troposphere delay modeling for SLR data based on direct ray-tracing utilizing numerical weather models (NWMs) derived from atmospheric infrared sounder (AIRS) to properly consider the impact of the azimuthal asymmetry. They found that neglecting horizontal gradients may provide to a deterioration of SLR observations at the level of 50 mm at 10\(^{\circ }\) elevation angles. Hulley and Pavlis (2007) compared different methods of applying horizontal asymmetry of the troposphere above SLR stations. The 3D ray-tracing method based on European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) resulted in the relative reduction of the variance of 23%, whereas adding ray-trace gradient correction to the standard solutions reduced the variances by 11%. However, the method employing the 3D ray-tracing for each SLR observation has never been employed for operational products. Therefore, simpler solutions with adding gradient corrections are preferable despite their lower accuracy.

Wijaya and Brunner (2011) proposed a promising method based on two frequencies of SLR observations to estimate laser beam propagation delay in the atmosphere and water vapor effects. However, this approach requires the precision of measurements at the level of a few micrometers which is beyond the current SLR stations’ capabilities. Only two SLR stations, Zimmerwald and Concepcion, were performing simultaneous SLR observations at two wavelengths. Currently, two-frequency SLR observations are practiced only intermittently due to the need of employing two independent detectors and due to the fact that the infrared detectors are typically characterized by lower accuracy than detectors for green lasers (Courde 2016).

Boisits et al. (2018) introduced so-called Vienna Mapping Function-3 for optical frequencies (VMF3o) and proposed a separation of the SLR mapping function into hydrostatic and wet components, instead of using a common mapping function coefficients as in the case of FCULa. Moreover, Boisits et al. (2018) performed a test employing the wet zenith delay based on numerical weather models and hydrostatic zenith delay based on Mendes and Pavlis (2004) model and meteorological data collected at SLR stations. This hybrid approach reduced the SLR residuals for the majority of SLR stations; however, the initial tests were performed only for 1 year (2005).

Drożdżewski and Sośnica (2018) confirmed that SLR observations are sensitive to atmospheric asymmetry through the estimation of horizontal gradients from SLR observations as additional parameters. The long-term mean values of horizontal gradients derived from SLR observations show a good agreement with the NWM and a moderate agreement with GNSS-derived gradients. However, increasing the number of estimated parameters in SLR solutions has a negative impact on SLR station coordinate repeatability; thus, the number of estimated parameters should be minimized to avoid the deterioration of other parameters due to a low number of SLR observations when compared to GNSS.

Today, the SLR technique faces the challenging requirements posed by the Global Geodetic Observing System which requests 1 mm of stations coordinates stability and 0.1 mm/year of station velocity stability. The International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) Conventions 2010 (Petit and Luzum 2011) suggest that one of the limiting factors in SLR solutions is due to neglecting the horizontal gradients in troposphere delay models. Fulfillment of this condition is needed for high-quality reference frames which will be employed, for instance, for monitoring glaciers’ melting and to improve the consistency between space geodetic techniques (Plag and Pearlman 2009). Adding gradient corrections to standard models is practiced in individual technique solutions of space geodesy, such as GNSS solutions. However, the impact of neglecting horizontal gradients on the geodetic parameters estimated from SLR observations has not yet been assessed, including the impact on geocenter coordinates, stations coordinates, Earth orientation parameters, and the global scale.

The paper has the following structure: In Sect. 2, we describe the current status of troposphere delay modeling in SLR measurements and introduce the Potsdam Mapping Function (PMF) as well as horizontal gradients derived from NWM dedicated for optical frequencies. In Sect. 3, we describe the results of utilization of PMF with first- and second-order horizontal gradients on SLR-derived parameters, such as station coordinates, geocenter coordinates, Earth rotation parameters, and the global scale using SLR observations to LAGEOS. Subsequently, we introduce results of PMF impact on SLR observations to the low-orbiting satellite Sentinel-3A. Finally, in Sect. 4, we summarize the results and introduce the best solution for the SLR community.

2 Methodology

2.1 The current status of troposphere delay modeling in SLR measurements

The model recommended by the IERS Conventions 2010 (Petit and Luzum 2011) for troposphere delay modeling in SLR solutions was originally proposed by Mendes and Pavlis (2004) with the mapping function FCULa proposed by Mendes et al. (2002). The recommended mapping functions are based on the truncated form of the continued fraction in terms of 1 / sin(e) (Marini 1972):

where e describes the elevation angle of an observation and \(a_{1}\), \(a_{2}\), \(a_{3}\) are the mapping function coefficients. The same coefficients are used for the sum of the wet and hydrostatic zenith delay. The mapping function coefficients were estimated at 22 elevation angles (from \(3^{\circ }\) to \(10^{\circ }\) with \(1^{\circ }\) resolution and from \(10^{\circ }\) to \(90^{\circ }\) with 5\(^{\circ }\) resolution). The parameterization of FCULa requires meteorological information about surface temperature \(t_s\), station latitude \(\varphi \), the orthometric height H. The values of coefficients \(a_i\), with i being equal to 1,2,3, read as:

The mapping function coefficients were derived using 1 year of radiosonde data (1999). The RMS for FCULa is equal to 1 mm, 4 mm, and 16 mm, respectively, for elevation angles equal to 15, 10\(^{\circ }\) and 6\(^{\circ }\). The procedure is described precisely by Mendes (1999). The main limitation of this model is neglecting the modeling of horizontal refractivity at a site, which can be described through horizontal gradients (Hulley and Pavlis 2007).

2.2 Potsdam Mapping Function (PMF)

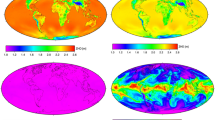

Different characteristics of optical SLR wavelengths (usually equal to 532 nm) in comparison with GNSS and VLBI techniques require the dedicated approach of troposphere delay modeling including the determination of horizontal gradients. SLR observations are performed only in cloudless weather conditions. As a result, the number of observations is limited and it falls in the range from a few to 400 observations per week for one station. Therefore, the number of estimated parameters from SLR should be limited to the necessary minimum. Retrieving troposphere parameters including horizontal gradients from SLR observations as additional parameters leads to the deterioration of other geodetic parameters despite reducing the residuals and a good agreement between NWM gradients and SLR-derived gradients (Drożdżewski and Sośnica 2018). Due to this fact, we propose to extend the currently used troposphere delay model by adding horizontal gradients derived from NWM. Figure 1 shows the difference between the North gradient derived for SLR observations (right) and microwave observations (left) based on NWM. Due to different sensitivities to the wet delays in SLR and microwave techniques, more fine structures of the gradient are visible for microwave gradients that are also characterized by high temporal variabilities. The SLR gradients are much more predictable as they are dominated by the atmospheric pressure (the hydrostatic part); however, the longest wavelengths for SLR and microwaves are consistent. The high predictability of atmospheric pressure, which dominates in the SLR delays, allows generating horizontal gradients based on NWM and introducing them as a priori models to the SLR solutions. In this way, the estimation of additional parameters in SLR solutions is avoided, thus stabilizing the SLR solutions.

Comparison of the horizontal gradient distribution for SLR observations (right) and for GNSS observations (left) derived from ray-tracing in one 6-h model with the resolution of \(0.5^{\circ } \times 0.5^{\circ }\) for 14 May, 2017. Top figures show the North gradient component, whereas the bottom figures show the East gradient component

The PMF coefficients are derived using ray-tracing algorithm developed by Zus et al. (2014) and NWM. For each station, 120 slants factors were computed with time resolution equal to 6 h. In this paper, we examine three approaches of new troposphere delay model for SLR in comparison with the standard troposphere delay model that is currently recommended by the IERS Conventions. In the first case, the mapping function will be replaced by a mapping function derived from a NWM, hereinafter referred to as PMF (for details, see Zus et al. 2015), with employing the zenith delay \((d^{z}_\mathrm{atm})\) that is based on the Mendes and Pavlis (2004) model and meteorological records registered at SLR stations:

In the second case, we use the same \((d^{z}_\mathrm{atm})\) and PMF and additionally the associated discrete linear PMF horizontal gradients with the Chen and Herring (1997) mapping function \(m_\mathrm{g}\) that was originally dedicated for microwave observations:

where \(G_{N}\) and \(G_{E}\) describe the first-order discrete horizontal gradients, the North and East components, respectively, for the azimuth A. In the third case, we use the \(d^{z}_\mathrm{atm}\) multiplied by the PMF with the first- and the second-order horizontal gradients including \(G_{NN}\), \(G_{NE}\), and \(G_{EE}\) (Douša et al. 2016):

In equations 4 and 5, \(m_\mathrm{g}\) denotes the Chen and Herring (1997) mapping function for horizontal gradients:

Despite that the PMF model contains also the zenith delays, the Mendes and Pavlis (2004) model is used in all cases. This is dictated by the fact that the zenith delays can be better modeled using the meteorological measurements collected at SLR stations simultaneously with SLR measurements than when using NWM. Table 1 characterizes the derivation of mapping function coefficients and corresponding gradients.

Differences between PMF and FCULa mapping functions projected onto elevation angles of 10\(^{\circ }\), 15\(^{\circ }\), and 20\(^{\circ }\) as a function of time in 2007 for four core SLR stations: Graz and Zimmerwald from the northern hemisphere and Yarragadee and Mt Stromlo from the southern hemisphere

The tropospheric model consists of mapping function coefficients \(a_{1}\), \(a_{2}\), \(a_{3}\) (Eq. 1) and horizontal gradients of the first and second orders (Eqs. 4 and 5). The tropospheric parameters are estimated for all SLR stations with time resolution equal to 6 h. Details on the tropospheric parameter estimation are provided in Appendix of Douša et al. (2016).

Figure 2 presents the mapping function coefficients derived from FCULa (Mendes et al. 2002) troposphere delay model (in black) and PMF model (in blue) for the period 2007.0–2008.0. Figure 2 shows the example of two stations: one from the northern hemisphere (Graz, left) and one from the southern hemisphere (Yarragadee, right). The \(a_1\) coefficient (top left) derived from FCULa assumes higher values than the PMF function. The \(a_2\) and \(a_3\) coefficients are shifted toward positive values in case of FCULa by about 5% and 6%, respectively, when compared to PMF. The coefficients \(a_2\) and \(a_3\) for Graz (7839), moreover, show a clear annual signal in PMF, which is remarkably smaller in the case of FCULa.

For 7090 and the \(a_1\) coefficient, the FCULa is characterized by a large temporal variability, whereas PMF seems to be much more smoothed. The differences at the mean level of 5% of the \(a_1\) coefficient lead to a difference of 5 mm of the slant delay for the elevation angle of 15\(^{\circ }\). This difference is significant as it does not allow achieving the GGOS goals requesting for sub-millimeter accuracy for models used in geodetic data reduction. The maximum difference between PMF coefficients derived from NWM and FCULa is at the level of 14% for the \(a_1\) coefficient.

Figure 3 shows the differences in tropospheric delays at the elevation of 10\(^{\circ }\), 15\(^{\circ }\), and 20\(^{\circ }\) calculated on the basis of FCULa and PMF coefficients for 2007. For two stations located in the northern hemisphere, Graz and Zimmerwald, a clear annual pattern is visible in differences. During the summertime, FCULa assumes greater values than the PMF model, whereas, in the winter, PMF is greater than FCULa. For two stations from the southern hemisphere, the effect is opposite but not as prominent as in the case of European stations. One has to bear in mind that FCULa is based mostly on the temperature readings from the SLR stations (\(t_s\) from equation 2), whereas the PMF coefficients consider the full atmospheric state for 10 different ray-directions. Differences, such as those shown in Fig. 2a, may cause systematic annual effects in all SLR-derived parameters. Figure 4 shows the asymmetry of the tropospheric delays using first- and second-order gradients calculated as a long-term mean in 2007 and plotted as a function of the local azimuth. Typically the effect of gradients reaches the level of 12 mm for 10\(^{\circ }\) of the elevation angle. For most of the SLR stations, the first-order gradients are fully sufficient to capture most of the atmosphere asymmetry. For Arequipa, the second-order gradients change, however, significantly the total effect, and the maximum value of asymmetry reaches 24 mm when compared to 12 mm when considering only the first-order gradients. However, most of the SLR observations to LAGEOS are collected above the elevation angle of 10\(^{\circ }\); thus, the total effect of the atmosphere asymmetry is smaller. From the analysis of the differences between the first- and second-order gradients, we conclude that for most of the SLR stations using the first-order gradients should be sufficient. However, we perform a series of tests of differences between solutions with and without second-order gradients and their impact on global geodetic parameters to provide recommendations.

2.3 SLR observations

We process 11 years of SLR observations to passive geodetic satellites LAGEOS-1 and LAGEOS-2 for the period 2007.0 to 2018.0 to validate different ways of troposphere modeling. The satellites orbit at the heights of 5.860 km and 5.620 km with inclination angles equal to 109.84\(^{\circ }\) and 52.62\(^{\circ }\) for LAGEOS-1 and 2, respectively (Pearlman et al. 2019). The processing is performed using a modified version of the Bernese GNSS software (Dach et al. 2015) which allows for extended troposphere delay modeling for SLR data including PMF and horizontal gradients. Station coordinates for the test period are realized using the a priori reference frame SLRF2014 with modeling the post-seismic deformation for the same set of the stations as in the International Terrestrial Reference Frame ITRF2014 (Altamimi et al. 2016). We apply the no-net-rotation and no-net-translation constraints on the set of verified core stations following the list from the International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS) Data Handling file. The station-specific center-of-mass corrections for LAGEOS satellites are used as detector- and time-specific. Range biases are estimated only for selected stations according to the ILRS Data Handling recommendations. The remaining models used in the presented solution are consistent with the standards used by the ILRS Analysis Standing Committee with details described by Drożdżewski and Sośnica (2018).

Hulley and Pavlis (2007) studied the impact of troposphere asymmetry on SLR observation residuals. In this study, we analyze the impact of employing troposphere gradients not only on SLR residuals, but also on estimated global geodetic parameters, such as pole coordinates, length of day (LOD), station coordinates, and geocenter coordinates, as listed in Table 2. UT1-UTC is parameterized as piecewise linear with the middle parameter fixed to the IERS-C04-14 series because the absolute value of UT1-UTC can be derived only from VLBI or Lunar Laser Ranging data. LOD is then calculated as a time derivative of UT1-UTC. Pole coordinates and geocenter coordinates are estimated with loose constraints of 1-m imposed thereon.

3 Results

3.1 Analysis of observation residuals

We analyze SLR observation residuals from the period 2007.0 to 2018.0. In total, over 1.5 million observations to passive satellites, LAGEOS-1 and LAGEOS-2, were collected by 49 SLR stations. Figure 5 shows the differences of standard deviations of observation residuals (STD) between PMF (Eq. 3), PMF with first-order gradients (O1, Eq. 4), and PMF with the first- and second-order gradients (O1 \(+\) O2, Eq. 5) with respect to the standard solution based on the IERS conventional models (FCULa without gradients, Eq. 2). The negative value denotes the improvement of the PMF solutions with respect to the IERS conventional approach that is based on FCULa. The largest improvements at the level of 0.2 mm are obtained for stations Graz and Grasse. The STD of SLR observations for best-performing SLR stations is at the level of 6–8 mm; thus, 0.2 mm of the difference corresponds to about 3% of the improvement for all observations or 9% of the variance improvement which is consistent with results provided by Hulley and Pavlis (2007). Moreover, we see in Fig. 5 an insignificant difference between solutions with the first-order horizontal gradients (O1) and higher-order horizontal gradients (O1 \(+\) O2). For the majority of the stations, we observe a moderate improvement due to using the PMF with the magnitude up to 0.05 mm for Graz and a considerable improvement of residuals due to using horizontal gradients (O1). Only for some stations, such as Hartebeesthoek and Haleakala, a minor degradation of solutions is present when using PMF or PMF with gradients. A degradation when using PMF is observed for the Riga station; however, this station is affected by substantial range biases (e.g., Arnold et al. 2018).

Box plots of SLR observation residuals to LAGEOS-1/2 including only observations below 15\(^{\circ }\) of the elevation angle. The blue box describes 25th and 75th percentiles, the red central line describes the median value, the whiskers describe the most extreme data points without outliers, and the red ‘\(+\)’ signs denote the outliers

Figure 6 presents box plots of residuals for observations collected at low elevation angles, that is below 15\(^{\circ }\). Not all SLR stations track LAGEOS satellites below 15\(^{\circ }\) and only one station, Grasse, tracks satellites down to 7\(^{\circ }\) of the elevation angle. Some stations, such as Herstmonceux, track satellites only down to 30\(^{\circ }\) at daytime and 25\(^{\circ }\) at nighttime because otherwise special permissions are required for SLR tracking at stations located in the international airport proximities. Figure 6 shows improvements of interquartile range (IQR) for solutions with horizontal gradients (O1 and O1 \(+\) O2). The main improvement for single observation residuals is up to 6 mm. For the station Yarragadee, which belongs to the most productive laser stations, we see an improvement of IQR at the level of 1.5 mm for solutions considering horizontal gradients. For the station Grasse, we see an improvement of IQR at the level of 1.7 mm for solutions when considering first-order horizontal gradients. The value of IQR for the solution with higher-order horizontal gradients (PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2) is the same as in solutions with first-order gradients (PMF \(+\) O1); however, the median value (offset) increases by 2 mm when adding the second-order gradients. For Graz, the IQR reaches 12 mm for solutions with the first-order horizontal gradients, whereas the IQR for the standard FCULa solution is by 1.1 mm larger. For the station Greenbelt, we observe a small deterioration of IQR of SLR residuals; however, the number of outliers is reduced and the median value for solutions with the first-order horizontal gradients is closer to zero when compared to the standard FCULa solution.

3.2 Station coordinates

Differences of stations coordinate repeatability between solutions based on PMF with respect to the standard solution based on the IERS models (FCULa, no gradients). The negative value denotes improvements for solutions based on the PMF models; positive values correspond to a better repeatability in the standard IERS solution

We analyze the impact of horizontal gradients on the stability of estimated station coordinates as differences between solutions with PMF models and the standard FCULa solutions. Figure 7 shows the effect on core SLR stations. The main impact of horizontal gradients is noticed for the North component and reaches up to 5% for stations Yarragadee and Greenbelt. However, we also observe a deterioration for the station Wettzell at the level of 2%. However, one has to keep in mind that station Wettzell during the analyzed period had some technical issues with pressure records and detectors, and in the result, a special handling with the estimation of range bias is recommended for this station by the ILRS Analysis Standing Committee (ILRS Analysis Standing Committee discussion 2018, Riepl et al. (2019)). The maximum value of the improvement for the East component due to PMF amounts up to 5% for the station Graz. Only for stations Herstmonceux and Wettzell, we do not observe notable improvements.

The impact of PMF and horizontal gradients is illustrated in Fig. 8 for the station Yarragadee, which has provided the largest number of solutions in the analyzed period. We observe the main impact of PMF, as well as horizontal gradients on the North coordinate component, which is consistent with Fig. 1 showing the ‘bulk’ of the atmosphere near the equator that leads to a systematic gradient with a dominating North component. The amplitude of the annual signal is equal to 0.7 mm for a solution with PMF \(+\) O1 for the North component when compared to the standard FCULa solution (see Fig. 1). The differences of the estimated station coordinates reach the level of 2 mm, 1.2 mm, and 0.2 mm for the North, East and Up components, respectively (see Fig. 9). The East component is affected more by adding first-order gradients (up to 0.9 mm) than when changing the mapping function (up to 0.3 mm).

The Up component is affected to the lesser extent because in all solutions the same zenith delay function is employed with differences only for the mapping function and gradients, which affect most the low elevation observations and thus the horizontal station components. Figure 9 shows that the currently neglected gradients of the troposphere delay cause differences in estimated station coordinates at the 1–2 mm level.

3.3 Earth rotation parameters derived from SLR

SLR station coordinates are derived in the terrestrial reference frame, whereas the estimated LAGEOS orbits are given in the inertial, celestial reference frame. Transformation parameters between celestial and terrestrial frames include nutation and precession parameters that are assumed to be known, LOD and pole coordinates with sub-daily tidal corrections. The estimated 1-day pole coordinates are realized by the no-net-rotation constraint imposed on the station coordinates derived from 7-day solutions. Figure 10 shows the differences between standard SLR solutions based on FCULa and solutions with PMF, PMF with first-order gradients, and PMF with first- and second-order gradients. Changing the mapping function from FCULa to PMF has no systematic effect on estimated pole coordinates because the mean differences do not exceed 1 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\). Only a small systematic effect is visible for the LOD component with the amplitude of the annual signal at the level of 0.2 \({\upmu }\)s/day. The situation is completely different when comparing the solution with gradients (PMF \(+\) O1) to the standard solution (see green line in Fig. 10). The X and Y pole coordinates are systematically shifted by 20 and 24 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\), respectively, due to considering the first-order gradients. The second-order gradients have a minor impact below 1 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\). The horizontal gradients introduce also an annual signal in the differences with the amplitude of up to 4 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\). The Earth rotation parameters are thus systematically different between each other when considering and neglecting a priori troposphere gradients.

To address the question which solution is better: with or without gradients, we compare pole coordinates derived from SLR solutions with the combined IERS-C04-14 (Bizouard et al. 2018) series published by the IERS. The IERS-C04-14 series is based on four space geodetic techniques, where the dominating impact on pole coordinates comes from GNSS and the dominating impact on UT1-UTC and LOD comes from VLBI.

Table 3 shows the differences between four solutions: standard, PMF, PMF \(+\) O1, PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2 with respect to IERS-C04-14. For solutions with horizontal gradients, we see an improvement of the mean offsets from 22 to 2 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\), and from 38 to 14 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\) for the X and Y components of pole coordinates, respectively. The spectral analysis of the differences with C04 (not shown here) provides a reduction of the amplitude of the annual signal for solutions with horizontal gradients for the X component at the level of 4 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\), which means that the SLR solutions including horizontal gradients become closer to the IERS-C04-14 series and thus to other space geodetic techniques.

In the considered period, 2007–2018, the number of weekly LAGEOS solutions is \(n=574\). The RMS of differences of the X and Y pole coordinates from one weekly solution is at the level of 160–185 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\). Assuming the equal weights for all pole coordinate solutions \({\sigma }_{i}\), the error of the mean pole offset from SLR \({\sigma }_\mathrm{mean}\) reads as:

Hence, the error of the mean SLR pole offset for the X and Y components based on 574 weekly solutions is at the level of 7 and 8 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\), respectively. Thus, one can conclude that the horizontal gradients of troposphere delay have a significant impact on estimated pole coordinates of 20 and 24 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\) for the X and Y components, respectively, based on t-test with the confidence intervals \(1-\alpha =0.95\). On the other hand, the impact of the second-order gradients and PMF mapping function does not significantly change the mean pole coordinates derived from SLR observation to LAGEOS.

3.4 Impact of horizontal gradients on geocenter coordinates

SLR is one of space geodetic techniques that provides information about the geocenter motion. Currently, the SLR-derived geocenter motion is superior when compared to other techniques, such as GNSS, low-orbiting kinematic solutions (Tseng et al. 2017) or inverse methods (Glaser et al. 2015), due to observations to passive geodetic satellites for which the non-gravitational orbit perturbations are minimized thanks to low area-to-mass ratios.

The geocenter coordinates are determined by the no-net-translation constraint imposed on the SLR core stations which allows the SLR stations to have their origin in the SLRF2014 reference frame origin and the LAGEOS orbits to have their origin in the Earth’s center of mass. Again, we compare SLR solutions based on PMF, PMF \(+\) O1 as well as PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2 with respect to the standard SLR solutions based on FCULa. Figure 11 shows that both changing the mapping function and including gradients have a sub-mm effect on estimated geocenter coordinates. PMF has the impact only on the Z component. Horizontal gradients affect Y and Z components, whereas the X component seems to be unaffected. The solution PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2 is almost the same as the PMF \(+\) O1 solution; thus, both solutions are overlapped in Fig. 11.

The mean shift in solution with PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2 is up to \(0.04, -0.13, -0.04\) mm for the X, Y, and Z components which suggests that the currently used origin of the ITRF realization may be affected by neglecting the horizontal gradients in SLR solution (Table 3). Even if the effect is at the sub-mm level with the amplitudes of the annual signal of up to 0.2 mm (see Fig. 11), the misinterpretation of or neglecting this effect may have the impact on a proper interpretation of the geocenter motion. Geocenter coordinates are used to correct satellite altimetry and gravimetry data derived, e.g., from Jason or GRACE missions Baur et al. (2013) and Desai and Ray (2014). The magnitude of the sea-level rise is at the level of 3.4 mm per year; thus, geocenter coordinates have to be known with sub-mm accuracy and freed from systematic effects to avoid a misinterpretation of the eustatic sea-level rise. The mean offsets of the PMF \(+\) O1 solution with respect to the standard solution exceed the 3-sigma values of the long-term mean for the X and Y components and thus can be considered as significant (see Table 4).

3.5 Impact of PMF on SLR observations to Sentinel-3A

Sentinel-3A is equipped with a retroreflector array whose main purpose is the validation of the GNSS orbits (Arnold et al. 2018). The satellite orbits at the height of 804 km in the sun-synchronous orbit with the inclination of 98.65\(^{\circ }\). Low-orbiting satellites due to short distances (in direction close to zenith) are more challenging targets to observe in the high elevation angles by SLR stations, and thereupon, for these segments of satellite passes more data are collected at low elevation angles, when compared to LAGEOS or GNSS passes. Therefore, SLR observations to low-orbiting satellites are particularly burdened with the impact of horizontal asymmetry, mapping functions, and other issues related to proper troposphere delay modeling.

We analyze the set of 1-year SLR observation residuals to satellite Sentinel-3A. SLR observations are compared to 1-day GPS-based reduced-dynamic orbits determined by the Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern in Switzerland (AIUB) with correcting SLR biases and station coordinates as described by Arnold et al. (2018). Sentinel-3A is primarily the altimetry mission; thus, the GPS receiver installed on board the satellite is of very high quality to guarantee the orbit quality in the radial direction better than 2 cm. Sentinel-3A is thus a low-orbiting target intensively tracked by SLR stations at low elevation angles with high-quality reference orbits, which make Sentinel-3A a very good target for testing different approaches of SLR troposphere delay modeling.

Figure 12 shows differences of IQR observation residuals in PMF solutions with respect to the standard solution based on FCULa. IQR values are more robust than RMS when observations are affected by outliers. For stations Wettzell, Matera, Zimmerwald, Potsdam, and Greenbelt, we observe improvements of IQR at the level over 0.5–1.2 mm due to using PMF or PMF with gradients. However, for the station Haleakala in Hawaii, a deterioration of IQR at the level of 0.7 mm is noticed. This fact may be caused by the poor horizontal resolution of the underlying NWM in this location. Nevertheless, the majority of analyzed stations shows improvements for solutions with PMF and horizontal gradients.

In order to evaluate the impact of troposphere delay modeling not only on observation residuals, but also on geodetic parameters, we generated a solution with estimating station coordinates. First, we set up daily normal equations including SLR observations to Sentinel-3A in 2017 and station coordinates for each station as parameters. The daily solutions were generated for the standard FCULa solution, PMF, PMF \(+\) O1, and PMF \(+\) O1 \(+\) O2. Then, we stacked all daily normal equations to generate one annual solution separately for solutions with different troposphere delay handlings. Eventually, we estimated parameters of the Helmert transformation between different annual solutions. In this way, the whole effect of including PMF and horizontal gradients is accumulated by the station coordinates in Sentinel-3A solutions, as opposed to the LAGEOS solutions, where the effect is distributed among all estimated parameters: station coordinates, geocenter, Earth rotation parameters, and LAGEOS orbits.

Figure 13 shows results from the Helmert transformation of the cumulative solution mentioned above, with station coordinates and without estimating any additional parameters. We observe a dependency of systematic effects with respect to the station latitude for the North and Up components. The effect of the horizontal gradients is markedly negative for stations located in the southern hemisphere and positive for stations located in the northern hemisphere for the North and Up components. The impact of neglecting tropospheric horizontal gradients is in the range from \(-2\) to 2 mm.

Figure 14 shows results from the Helmert transformation of accumulated annual solutions using different modeling approaches with respect to the standard FCULa solution. The usage of the PMF causes a change in the scale of 3 mm, whereas adding horizontal gradients changes additionally the estimated scale by 0.4 mm. The impact of the PMF and including horizontal gradients on translation parameters, which correspond to the network origin shift (realized only by observations to Sentinel-3A), are at the level of 1.3, -0.8, and 3.3 mm for X, Y, and Z components, respectively. These values are much larger when compared to the effect on LAGEOS-derived geocenter motion. Figure 14 shows no effect on rotation parameters. We may conclude that different handlings of the troposphere delay may have the effect on the SLR translation parameters from \(-0.8\) to 3.3 mm for targets such as Sentinel-3A characterized by a large number of SLR observations at low elevation angles.

4 Conclusions and recommendations

The currently employed model for the SLR observation reduction assumes a full symmetry of the troposphere above SLR stations. This assumption causes a small but systematic effect in SLR-derived products and inconsistency between SLR and other space geodetic techniques. In this study, we developed and tested the PMF dedicated to optical observations and the impact of associated first- and second-order horizontal gradients of the troposphere delay. All tropospheric parameters were estimated utilizing NWM data, but the Mendes–Pavlis (2004) model was used for the zenith delay. The PMF models were validated using 11 years of SLR observations to LAGEOS-1/2 and 1 year of SLR observations to Sentinel-3A with a special focus on observation residuals, estimated station coordinates, Earth rotation parameters, and geocenter coordinates; thus, the fundamental products were derived from SLR.

The extended mapping function with horizontal gradients improves the observations residuals for low elevation angles. The interquartile ranges of SLR residuals to LAGEOS can be reduced by even 1.7 mm, for SLR observations at the elevation angles below 15\(^{\circ }\), which constitute 7% of the total amount of observations in this campaign period.

Including first-order horizontal gradients changes the estimated station coordinates at the millimeter to a few millimeters levels. The largest effect up to 2 mm is for the North component, whereas the East component is affected by up to 1.2 mm in the case of the Yarragadee station.

The differences between SLR-derived X and Y pole coordinates and the combined, multi-technique IERS-C04-14 series are reduced by 20 and 24 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\), respectively. The mean bias is reduced for the X pole component from 22 to 2 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\) and for the Y component from 28 to 14 \({\upmu }\mathrm{as}\) for solutions with horizontal gradients. The change of the mapping function from FCULa to PMF has no significant impact on SLR-derived Earth rotation parameters. Including the horizontal gradients in SLR solutions improves thus the consistency between Earth rotation parameters derived from SLR and other space geodetic techniques, such as GNSS and VLBI, which consider the troposphere asymmetry in data processing.

When processing SLR observations to low-orbiting satellites, such as Sentinel-3A, the effects due to horizontal gradients and network translations are more prominent due to the greater proportion of SLR observations collected at low elevation angles. For most of the SLR stations, the interquartile observation residuals are reduced by 0.5–1.2 mm when considering PMF with horizontal gradients with respect to the standard SLR solution. The origin of the SLR network realized only on Sentinel-3A observations is shifted by \(-1\)–3 mm because of considering gradients; thus, it exceeds the current target of GGOS station coordinate accuracy determination requested for global geodetic reference frames. Hence, we propose to extend the currently used troposphere delay model by considering the first-order tropospheric horizontal gradients. We found that the second-order tropospheric gradients have just small impact on SLR-derived products. The second-order horizontal gradients bring measurable results in dynamic weather conditions; however, the SLR stations provide observations only in good and cloudless conditions so that the second-order horizontal gradients can be neglected to simplify the troposphere delay model and to minimize the number of input parameters without deteriorating the solution. However, neglecting the first-order gradients does substantially impact the SLR products.

Data availibility statement

The SLR LAGEOS-1 and 2 normal point data were obtained through the online archives of the Crustal Dynamics Data Information System (CDDIS), NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, https://cddis.nasa.gov/ The time series of troposphere delay horizontal gradients are publicly available from GFZ-Potsdam ftp://ftp.gfz-potsdam.de/home/kg/kyriakos/PMF/SLR/. Analysis was conducted in the modified version of the Bernese GNSS Software http://www.bernese.unibe.ch/. ILRS data handling files and satellite center-of-mass corrections are available at: https://ilrs.dgfi.tum.de/index.php?id=6

References

Altamimi Z, Rebischung P, Métivier L, Collilieux X (2016) ITRF2014: a new release of the international terrestrial reference frame modeling nonlinear station motions. J Geophys Res 121(8):6109–6131. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JB013098

Arnold D, Montenbruck O, Hackel S, Sośnica K (2018) Satellite laser ranging to low Earth orbiters: orbit and network validation. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1140-4

Balidakis K, Nilsson T, Zus F, Glaser S, Heinkelmann R, Deng Z, Schuh H (2018) Estimating integrated water vapour trends from VLBI, GPS and numerical weather models: sensitivity to tropospheric parameterization. J Geophys Res 123:6356–6372. https://doi.org/10.1029/2017JD028049

Baur O, Kuhn M, Featherstone WE (2013) Continental mass change from GRACE over 2002–2011 and its impact on sea level. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-012-0583-2

Böhm J, Schuh H (2007) Troposphere gradients from the ECMWF in VLBI analysis. J Geod 81(6):403–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-007-0144-2

Böhm J, Hobiger T, Ichikawa R, Kondo T, Koyama Y, Pany A, Schuh H, Teke K (2010) Asymmetric tropospheric delays from numerical weather models for UT1 determination from VLBI Intensive sessions on the baseline Wettzell-Tsukuba. J Geod 84(5):319–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-010-0370-x

Böhm J, Möller G, Schindelegger M, Pain G, Weber R (2015) Development of an improved empirical model for slant delays in the troposphere (GPT2w). GPS Solut 19(3):433–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-014-0403-7

Bizouard C, Lambert S, Gattano C, Becker O (2018) Richard JY (2018) The IERS EOP 14C04 solution for Earth orientation parameters consistent with ITRF 2014. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1186-3

Boisits J, Landskron D, Sośnica K, Drożdżewski M, Böhm J. (2018) VMF3o enhanced tropospheric mapping functions for optical frequencies. Presented at:21 st international workshop on laser ranging, Canberra https://cddis.nasa.gov/lw21/docs/2018/papers/Session2_Boisits_paper.pdf

Chen G, Herring TA (1997) Effects of atmospheric azimuthal asymmetry on the analysis of space geodetic data. J Geophys Res 102(B9):20,489–20,502. https://doi.org/10.1029/97JB01739

Courde C (2016) Lunar laser ranging In Infrared. International Workshop on Laser Ranging (Potsdam), https://cddis.nasa.gov/lw20/docs/2016/presentations/27-Courde_presentation.pdf

Dach R, Lutz S, Walser P, Fridez P (eds) (2015) Bernese GNSS Software Version 5.2. User manual, Astronomical Institute, University of Bern, Bern Open Publishing, https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.72297

Desai Shailen D, Ray Richard D (2014) Consideration of tidal variations in the geocenter on satellite altimeter observations of ocean tides. J Geophys Res 41:0094–8276. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059614

Douša J, Dick G, Kačmařík M, Brožková R, Zus F, Brenot H, Stoycheva A, Möller G, Kaplon J (2016) Benchmark campaign and case study episode in central Europe for development and assessment of advanced GNSS tropospheric models and products. Atmos Meas Tech 9(7):2989–3008. https://www.atmos-meas-tech.net/9/2989/2016/

Drożdżewski M, Sośnica K (2018) Satellite laser ranging as a tool for the recovery of tropospheric gradients. Atmos Res 212:33–42

Glaser S, Fritsche M, Sośnica K, Rodríguez-Solano CJ, Wang K, Dach R, Hugentobler U, Rothacher M, Dietrich R (2015) A consistent combination of GNSS and SLR with minimum constraints. J Geod 89(12):1165–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0842-0

Heinkelmann R, Balidakis K, Phogat A, Lu C, Mora-Diaz JA, Nilsson T, Schuh H (2018) Effects of Meteorological Input Data on the VLBI Station Coordinates, Network Scale, and EOP. In: Freymueller JT, Sánchez L (eds) International symposium on earth and environmental sciences for future generations. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 195–202

Hulley GC, Pavlis EC (2007) A ray-tracing technique for improving Satellite Laser Ranging atmospheric delay corrections, including the effects of horizontal refractivity gradients. J Geophys Res 112:B06417. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JB004834

Landskron D, Böhm J (2018a) Refined discrete and empirical horizontal gradients in VLBI analysis. J Geod 92(12):1387–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1127-1

Landskron D, Böhm J (2018b) VMF3/GPT3: refined discrete and empirical troposphere mapping functions. J Geod 92(4):349–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-017-1066-2

MacMillan DS, Ma C (1997) Atmospheric gradients and the VLBI terrestrial and celestial reference frames. Geophys Res Lett 24(4):453–456. https://doi.org/10.1029/97GL00143

Marini JW (1972) Correction of satellite tracking data for an arbitrary tropospheric profile. Radio Sci 7(2):223–231. https://doi.org/10.1029/RS007i002p00223

Masoumi S, McClusky S, Koulali A, Tregoning P (2017) A directional model of tropospheric horizontal gradients in Global Positioning System and its application for particular weather scenarios. J Geophys Res 122(8):4401–4425. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD026184

Mendes VB (1999) Modeling the neutral-atmosphere propagation delay in radiometric space techniques. http://www2.unb.ca/gge/Pubs/TR199.pdf

Mendes VB, Pavlis EC (2004) High-accuracy zenith delay prediction at optical wavelengths. Geophys Res Lett 31(14). https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2004GL020308

Mendes VB, Prates G, Pavlis EC, Pavlis DE, Langley RB (2002) Improved mapping functions for atmospheric refraction correction in SLR. Geophys Res Lett 29(10):53–1–53–4. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GL014394

Niell AE (2000) Improved atmospheric mapping functions for VLBI and GPS. Earth Planets Space 52(10):699–702. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352267

Nilsson T, Soja B, Balidakis K, Karbon M, Heinkelmann R, Deng Z, Schuh H (2017) Improving the modeling of the atmospheric delay in the data analysis of the Intensive VLBI sessions and the impact on the UT1 estimates. J Geod 91(7):857–866. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-016-0985-7

Pearlman M, Arnold D, Davis M, Barlier F, Biancale R, Vasiliev V, Ciufolini I, Paolozzi A, Pavlis E, Sośnica K, Bloßfeld M (2019) Laser geodetic satellites: a high accuracy scientific tool. J Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01228-y

Petit G, Luzum B (2011) IERS Conventions 2010. IERS Technical Note 36. https://www.iers.org/IERS/EN/Publications/TechnicalNotes/tn36.html

Plag HP, Pearlman M (eds) (2009) GLobal geodetic observing system, meeting the requirements of a global society on a changing planet in 2020. Springer, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02687-4

Riepl S, Müller H, Mähler S, Eckl J, Klügel T, Schreiber U, Schüler T (2019) Operating two SLR systems at the Geodetic Observatory Wettzell: from local survey to space ties. J. Geod. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01243-z

Rocken C, Sokolovskiy S, Johnson JM, Hunt D (2001) Improved mapping of tropospheric delays. J Atmos Oceanic Technol. 18:1205–1213. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0426(2001)018<1205:IMOTD>2.0.CO;2

Tseng TP, Hwang C, Sośnica K, Kuo CY, Liu YC, Yeh WH (2017) Geocenter motion estimated from GRACE orbits: the impact of F10.7 solar flux. Adv Space Res 59(11):2819–2830

Wijaya DD, Brunner FK (2011) Atmospheric range correction for two-frequency SLR measurements. J Geod 85(9):623–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-011-0469-8

Zus F, Dick G, Douša J, Heise S, Wickert J (2014) The rapid and precise computation of GPS slant total delays and mapping factors utilizing a numerical weather model. Radio Sci 49(3):207–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013RS005280

Zus F, Dick G, Douša J, Wickert J (2015) Systematic errors of mapping functions which are based on the VMF1 concept. GPS Solut 19:277–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-014-0386-4

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Astronomical Institute of the University of Bern (AIUB) for providing the Sentinel-3A orbits and thank the International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS, Pearlman et al. 2019). The Wroclaw Centre of Networking and Supercomputing (www.wcss.wroc.pl) is acknowledged for providing the Computational Grant for using Matlab Software License No: 101979.

Funding

This work has been supported by the Polish National Science Centre (UMO-2015/17/B/ST10/03108).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D. and K.S. designed the research; K.B. and F.Z. derived the time series of PMF with horizontal gradients dedicated to SLR observations. M.D. performed the experiment, generated the SLR solutions, and wrote the manuscript with support from K.S.; K.S., F.Z., and K.B gave helpful suggestions during the internal and external reviewing processes.

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Drożdżewski, M., Sośnica, K., Zus, F. et al. Troposphere delay modeling with horizontal gradients for satellite laser ranging. J Geod 93, 1853–1866 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01287-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-019-01287-1