Abstract

High-speed rail (HSR) access promotes the interregional population flow and integrated market across cities in China. Using panel data of 286 cities in China from 2000 to 2018, we investigated the spatial employment effect of HSR by multi-period Difference-in-Difference (DID) model and staggered DID. We found that: First, HSR significantly enhances the spatial employment agglomeration, rationalization of three industrial-employment structures and the advancement of industrial structure in areas with HSR. Cities that open HSRs later generally get higher marginal benefit from HSR. Second, based on the change of regional accessibility caused by HSR, income and housing price are two channels affect spatial employment distribution; capital and labor are two channels affect the industrial-employment structure. Third, HSR has a greater spatial employment effect in peripheral cities than central cities, and HSR has a greater spatial employment effect in southern cities than northern cities. HSR has significantly promoted employment agglomeration in eastern China; it has a significant impact on the employment structure in Northeast China. Fourth, the effective radiation distance of HSR station is about 30 km. Labor market needs to pay more attention on the influences of new massive public transportation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the China city statistical yearbook, the statistics bulletin of the national economy and social development, the national railway bureau website and 12,360 railway website. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

In this paper, passenger trains with speeds of 200 km/h or above are defined as HSR trains.

By province, Eastern China includes: Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan. Central China includes Shanxi, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei and Hunan. Western China includes: Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Tibet, Shaanxi, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang. Northeastern China includes: Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang.

It means the second level of administrative divisions in China. 286 cities in prefecture-level and above were sorted out from the Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Cities from 2001 to 2019, due to the lack of data of some cities and the changes of administrative divisions in the past years.

Southern China includes Hainan, Guangdong, Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Jiangxi, Fujian, Jiangsu, Anhui, Hunan, Hubei, Sichuan, Chongqing, Shanghai and Zhejiang. Northern China includes Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Henan, Shandong, Xinjiang, Tibet, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi.

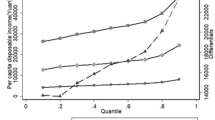

It is calculated by the data of China Labor Statistics Yearbook from 2001 to 2019. The spatial Gini coefficient of employed population is consistent with the calculation method of income Gini coefficient. Lorentz curve is drawn according to the cumulative proportion of employed population in urban units to the total employed population in different regions. The higher the coefficient is, the higher the spatial concentration of employment is.

Central cities refer to the cities municipalities directly under the central government, provincial capitals and sub-provincial cities.

References

Aguayo-Tellez E, Rivera-Mendoza CI (2011) Migration from Mexico to the United States: wage benefits of crossing the border and going to the U.S. interior. Politics Policy 39:119–140

Ahlfeldt GM, Feddersen A (2018) From periphery to core: measuring agglomeration effects using high-speed rail. J Econ Geogr 18:355–390

Albalate D, Fageda X (2016) High speed rail and tourism: empirical evidence from Spain. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 85:174–185

Banerjee A, Duflo E, Qian N (2020) On the road: access to transportation infrastructure and economic growth in China. J Dev Econ 145:102442

Beck T, Levine R, Levkov A (2010) Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J Financ 65:1637–1667

Bernard AB, Moxnes A, Saito YU (2014) Production networks, geography and firm performance. J Polit Econ 127(2):639–688

Braunerhjelm P, Borgman B (2006) Agglomeration, diversity and regional growth: the effect of poly-industrial versus mono-industrial agglomerations. Electronic working paper series No.71

Chen Z, Haynes KE (2017) Impact of high-speed rail on regional economic disparity in China. J Transp Geogr 65:80–91

Chenery H, Robinson S, Syrquin M (1986) Industrialization and growth: a comparative study. Oxford University Press, New York

Cheng Y-S, Loo BPY, Vickerman R (2015) High-speed rail networks, economic integration and regional specialisation in China and Europe. Travel Behav Soc 2:1–14

Degen K, Fischer AM (2017) Immigration and swiss house prices. Swiss Soc Econ Stat 153:15–36

Ding S, Ding Y, Wu D (2018) Research on the transformation of employment contradiction from quantity to quality in China. Economist 12:57–63

Dohmen TJ (2005) Housing, mobility and unemployment. Reg Sci Urban Econ 35:305–325

Donaldson D (2018) Railroads of the Raj: estimating the impact of transportation infrastructure. Am Econ Rev 108:899–934

Dong X (2018) High-speed railway and urban sectoral employment in China. Transp Res Part A Policy Pract 116:603–621

Dong Y-M, Zhu Y-M (2016) Can high-speed rail construction reshape the layout of China’s economic space—based on the perspective of regional heterogeneity of employment, wage and economic growth. China Ind Econ 10:92–108

Duffy-Deno KT, Dalenberg DR (1993) The municipal wage and employment effects of public infrastructure. Urban Stud 30:1577–1589

Dumais G, Ellison G, Glaeser, EL (1997) Geographic concentration as a dynamic process. NBER working paper series No.6270

Duranton G (2010) Labor specialization, transport costs, and city size. J Reg Sci 38:553–573

Duranton G, Turner MA (2012) Urban growth and transportation. Rev Econ Stud 79:1407–1440

Faber B (2014) Trade integration, market size, and industrialization: evidence from China’s national trunk highway system. Rev Econ Stud 81:1046–1070

Fan S, Zhang X, Robinson S (2003) Structural change and economic growth in China. Rev Dev Econ 7:360–377

Forslid R, Ottaviano GIP (2003) An analytically solvable core-periphery model. J Econ Geogr 3:229–240

Fujita M, Mori T (1997) Structural stability and evolution of urban systems. Reg Sci Urban Econ 27:399–442

Gardner J (2021) A primer on staggered DD. Working paper

He X (2019) Analysis and prospect of national labor market and rural development policy. Seeker 01:11–17

Heuermann DF, Schmieder JF (2019) The effect of infrastructure on worker mobility evidence from high-speed rail expansion in Germany. J Econ Geogr 19:335–372

Imbens GW, Rubin DB (2015) Causal inference for statistics, social, and biomedical sciences. Cambridge University Press, NewYork

Jackman R, Savouri S (1992) Regional migration in Britain: an analysis of gross flows using NHS central register data. Econ J 102:1433–1450

Johansson B, Klaesson J, Olsson M (2005) Time distances and labor market integration. Pap Reg Sci 81:305–327

Kim KS (2000) High-speed rail Developments and Spatial Restructuring: a case study of the capital region in South Korea. Cities 17:251–262

Kim H, Sultana S, Weber J (2018) A geographic assessment of the economic development impact of Korean high-speed rail stations. Transp Policy 66:127–137

Krugman P (1991) Increasing returns and economic geography. J Polit Econ 99:483–499

Leunig T (2006) Time is money: a re-assessment of the passenger social savings from Victorian British railways. J Econ Hist 66:635–673

Lin Y (2017) Travel costs and urban specialization patterns: evidence from China’s high speed railway system. J Urban Econ 98:98–123

Lin Y, Qin Y, Sulaeman J, Yan J, Zhang J (2020) Expanding footprints:the impact of passenger transportation on corporate locations. Social Science Electronic Publishing. Working paper. No. 15–19

Lucas RE (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monet Econ 22:3–42

Mackinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM (2000) Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci 1:173–181

Martin P, Rogers CA (1995) Industrial location and public infrastructure. J Int Econ 39:335–351

Meen G, Nygaard A (2010) Housing and regional economic disparities. Swiss National Bank Working Papers No. 5

Morris JM, Dumble PL, Wigan MR (1979) Accessibility indicators for transport planning. Trangsportation Research Part a: General 13:91–109

Munnell AH (1990) Why has productivity growth declined? Productivity and public investment. Engl Econ Rev 30:3–22

Ottaviano G, Tabuchi T, Thisse J-F (2002) Agglomeration and trade revisited. Int Econ Rev 43:409–435

Peter MJP (2003) The economic impact of the high-speed train on urban regions. Eur Reg Sci Assoc. ERSA conference papers ersa03p397

Picard PM, Toulemonde E (2006) Firms agglomeration and unions. Eur Econ Rev 50:669–694

Pissarides CA, McMaster I (1990) Regional migration, wages and unemployment empirical evidence and implications for policy. Oxf Econ Pap 42:812–831

Qin Y (2017) No county left behind? The distributional impact of high-speed rail upgrades in China. J Econ Geogr 17:489–520

Rabe B, Taylor MP (2012) Differences in opportunities? Wage, employment and house-price effects on migration. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 74:831–855

Redding SJ, Turner MA (2015) Transportation costs and the spatial organization of economic activity. Handb Reg Urban Econ 5:1339–1398

Rosenthal SS, Strange WC (2004) Evidence on the nature and sources of agglomeration economies. Handb Reg Urban Econ 4:2119–2171

Shao S, Tian Z, Yang L (2017) High speed rail and urban service industry agglomeration: evidence from China’s Yangtze river delta region. J Transp Geogr 64:174–183

Shaw S, Fang Z, Lu S, Tao R (2014) Impacts of high speed rail on railroad network accessibility in China. J Transp Geogr 40:112–122

Shi J, Zhou N (2013) How cities influenced by high speed rail development: a case study in China. J Transp Technol 3:7–16

Vickerman R (2018) Can high-speed rail have a transformative effect on the economy? Transp Policy 62:31–37

Vickerman R (2007) Recent evolution of research into the wider economic benefits of transport infrastructure investments. Joint transport research centre discussion papers

Wen Z, Ye B (2014) Analyses of mediating effects: the development of methods and models. Adv Psychol Sci 22:731

Yang X, Zhang D (2001) Endogenous structure of division of labor, endogenous policy regime, and a dual structure in economic development. Ann Econ Financ 1:203–221

Yin M, Bertolini L, Duan J (2015) The effects of the high-speed railway on urban development: international experience and potential implications for China. Prog Plan 98:1–52

Yu F, Lin F, Tang Y, Zhong C (2019) High-speed railway to success? The effects of high-speed rail connection on regional economic development in China. J Reg Sci 59:723–742

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Chinese National Funding of Social Sciences [Grant No. 18ZDA086]; Chinese National Funding of Social Sciences [Grant No. 20AZD071]. The funding body has no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of the data and write up of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Software, Formal analysis, Writing-original draft and Writing-Reviewing. DT: Funding acquisition. TB: Data curation. XW: Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors listed have approved the manuscript that is enclosed. The authors declare that there are no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest of the present article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgements: Thank for the China city statistical yearbook, the statistics bulletin of the national economy and social development, the national railway bureau website and 12360 railway website data supporting.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

This paper constructs the time point of counterfactual policy to conduct placebo test. If the employment effect of HSR is not significant under the time point of virtual policy, it proves the robustness of the conclusion. According to the actual opening time of HSR in each city, the net employment effect of HSR opening was estimated by advancing the policy time points of HSR opening in each region by one to five years respectively. Table

9 shows that the regression coefficients were not significant. These all proved the robustness of the results.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Tang, D., Bu, T. et al. The spatial employment effect of high-speed railway: quasi-natural experimental evidence from China. Ann Reg Sci 69, 333–359 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01135-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01135-9