Abstract

We consider a model for density-based topology optimization (TO) of stationary heat transfer problems with design-dependent internal convection in 3D structures with periodic design obtained by extruding a 2D design in 3D. The internal convection takes place at the interface between a solid material and a cooling fluid in internal channels through the design domain. The objective of the TO is to minimize the maximum temperature, which is approximated by means of an Lp norm. The finite element method is used to discretize the state problem and the resulting optimization problem is solved using gradient-based methods. The internal convection is modeled to be dependent on the design density gradient in the continuous problem. In discrete form, it is approximated as proportional to the difference in design densities of adjacent elements in the finite element mesh. The theory is illustrated by numerical examples based on a simplified guide vane geometry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Topology optimization (TO) enables design of intricate structures, which cannot be done as effectively by a classical trial and error approach. For instance, TO can be used in heat transfer problems for industrial gas turbine applications where some parts, e.g., combustor parts and turbine parts, are exposed to long-term hot gas flow exposure, with gas temperatures up to 1400–1700 °C. The components in that environment are in general designed with internal cooling features to ensure that the component fulfills life requirements. By using TO, the design of cooling channels and structures can be improved for turbine parts such as guide vanes and turbine blades. The improved cooling efficiency can be used to extend the time between overhauls and/or increase the power output.

In this work, we consider a heat transfer problem with convection and aim to minimize the maximum temperature of a periodic 3D structure, resembling a simplified guide vane geometry, by use of 2D design. The 2D design approach limits the number of design variables in the optimization problem, but keeps the complexity of a full 3D state problem, enabling, e.g., temperature gradients in 3D. A similar approach was taken by Haertel et al. (2018), but the 3D analysis was simply a validation of the model after the optimization was completed. Haertel and Nellis (2017) used periodic boundary conditions to develop a 2D model for heat exchangers in a thermal-fluid problem. However, in contrast to the present work, the periodic boundary conditions are still only implemented in a 2D model.

Stationary heat transfer problems have been the topic of several research papers (Dbouk 2017). Pure heat conduction problems can be solved by easy-to-implement TO codes in Matlab, and some codes are presented as open source for educational purposes (Bendsøe and Sigmund 2003; Liu and Tovar 2014). However, these codes are in standard versions restricted to minimizing thermal compliance, whereas in many applications, maximum temperature is probably more relevant as an objective.

The convection modeled in this problem is of two types: external convection on the boundaries of the design domain, and internal convection at the internal boundary in the interior of the design domain. Both types of convection are design dependent, leading to design-dependent load terms in the FE analysis, but in different ways. Thellner and Torstenfelt (2005) investigated design-dependent loads by means of a changing design domain, Zhou et al. (2016) considered an industrial application for heat transfer problems with design-dependent boundary conditions for external convection, and Ahn and Cho (2010) discussed design-dependent convection boundaries with a level set approach. Bruns (2007) discussed convection-dominated heat transfer problems and extended the design-dependent convection theory to cover also internal convection, by an approach where the internal convection is proportional to the change in design densities of two adjacent elements in the domain. A somewhat related approach was taken by Alexandersen (2011a, 2011b), and a similar approach is also taken in this work. Iga et al. (2009) and Dede et al. (2015) both used a density-based approach to model design-dependent convection, utilizing a so-called hat function to define the boundary. The hat function approach is not suitable, however, since it favors intermediate design density values, which are given a large cooling effect according to the definition of the hat function range.

2 The stationary heat transfer problem

Consider the design domain Ω in Fig. 1, consisting of a solid part Ωs and a fluid part Ωf, with the disjoint boundary parts ΓT ∪Γα ∪Γ1 ∪Γ2 = ∂Ω. Here, ΓT is where the temperature T0 is prescribed, Γα is where convection with heat transfer coefficient α and ambient temperature T∞ takes place, and Γ1 and Γ2 are boundaries of periodic boundary conditions. The internal convection takes place at the design-dependent internal boundary Γfs = ∂Ωf ∩ ∂Ωs, with a heat transfer coefficient β and an internal cooling fluid temperature TC.

Starting from energy balance and Fourier’s law of heat transfer, one obtains the following variational problem for the temperature T = T(x) in Ω at steady state:

where \(\mathcal {V}(T_{0}) = \{ u : u=T_{0} \ \text {on} \ {\Gamma }_{T},\ u|_{{\Gamma }_{1}}=u|_{{\Gamma }_{2}}\}\). The linear form ℓ is:

and the symmetric, bilinear form a is:

The conductivity k of the material is:

It may be noted that the last integrals in (2) and (3) imply the jump condition:

where ns is the outward unit normal to Ωs.

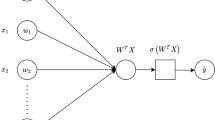

3 Design parametrization

The design is described by a function \(\hat {\rho }=\hat {\rho }(\tilde {\rho }(\rho ))(\boldsymbol {x}) \in [0,1]\) for all x ∈Ω, such that \(\hat {\rho } = 1\) represents solid material and \(\hat {\rho } = 0\) fluid. Here, ρ = ρ(x) is the design variable used in the optimization process, while \(\hat {\rho }\) is the physical variable, obtained through filtering, and entering into the state problem. The first filter, giving \(\tilde {\rho }(\rho )\), is a linear density filter (Bourdin 2001), implemented to avoid checkerboard patterns and mesh dependency (Sigmund and Petersson 1998). The second filter, giving \(\hat {\rho }(\tilde {\rho })\), converts the 2D design into 3D by extrusion in the out-of-plane direction. This means that the design is the same in every cut normal to one of the principle directions of the structure. An illustration is found in Fig. 2 for the discrete case.

Given the state problem (1) and the design described by \(\hat {\rho }\), a TO problem can be formulated based on the following parametrization:

where |⋅| denotes the absolute function, α0 is the nominal heat transfer coefficient on the external boundary, and ψ > 1 is a penalty exponent to get convection only on solid element boundaries. The internal boundary Γfs is approximated in (6) as an open set and not as an infinitesimally thin boundary. However, this fluid–solid interface region would ideally only be a thin layer.

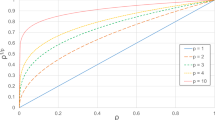

The objective in the optimization problem is to minimize the maximum temperature in the solid domain Ωs, a non-differentiable function with implicit design dependency. To obtain a differentiable function, the maximum temperature is approximated by means of an Lp norm, and this approximation is furthermore weighted with \(\hat {\rho }\) to remove the influence of the temperature in the fluid domain:

Here, \(T\left (\hat {\rho }(\boldsymbol {x})\right )\) solves the variational problem (1) for the design \(\hat {\rho }\) and κ < 1 is a penalty exponent inserted in order to give artificially high temperatures in regions with an intermediate design density, cf., stress penalization (Holmberg et al. 2013). Solutions containing such regions are undesirable since they lack physical meaning in 3D structures. Therefore, following Borrvall and Petersson (2001), a penalty term is added and the continuous version of the objective function is defined as:

where λ > 0 is a penalty factor and |Ωxy| is the size of the xy-plane.

4 Discrete problem

To solve the state problem (1), a standard Galerkin finite element (FE) method is used. The mesh consists of m elements in total, whereof mxy in the xy-plane (see Fig. 2). Density-based TO is used and the 2D design approach means that elements in one xy-layer of the mesh are assigned design variables, collected in a vector \(\mathbf {\boldsymbol {\rho }} \in \mathbb {R}^{m_{\text {xy}}}\). The discrete version of the linear density filter then reads \(\tilde {\mathbf {\boldsymbol {\rho }}} = \mathbf {H}^{B}\mathbf {\boldsymbol {\rho }}\).

Assuming a structured mesh similar to the one used in Liu and Tovar (2014), the discrete version of the 2D-to-3D filter, which makes \(\tilde {\mathbf {\boldsymbol {\rho }}} \in \mathbb {R}^{m_{\text {xy}}} \mapsto \hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }} \in \mathbb {R}^{m}\), reads:

in which I is an identity matrix of appropriate size. Combining both filters gives \(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }} = \mathbf {H}^{2\mathrm {D}}\mathbf {H}^{B}\mathbf {\boldsymbol {\rho }}\). Discretization of (1) eventually leads to the following matrix problem for the unknown nodal temperatures t:

where t0 collects the known nodal temperatures, \(\mathbf {K}(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }}) \in \mathbb {R}^{n\times n}\), \(\bar {\mathbf {K}}(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }}) \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n_{0}}\), and where n0 and n are the numbers of nodes with known and unknown temperatures, respectively. If the nodal temperatures on the periodic boundaries Γ1 and Γ2 are collected in t1 and t2, respectively, the periodicity condition t1 = t2 gives:

where tR contains the remaining nodal temperatures and I denotes identity matrices of appropriate sizes. Now, using (9) in (8) and multiplying with DT from the left yields:

This system has a unique solution \(\mathbf {t}_{p} = \mathbf {t}_{p}(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }})\), which satisfies the periodic boundary conditions on Γ1 and Γ2 for every admissible design and adequate choices of parameters ks, kf, α, and β.

The stiffness contribution in (3) from the design-dependent convection is evaluated over the design-dependent boundary \({\Gamma }^{h}_{fs}(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }})\), which is an approximation of the fluid–solid interface layer \({\Gamma }_{fs}(\hat {\rho })\) on the FE mesh:

where the function \((D_{\mathbf {n}_{e,k}}\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }})\) is defined as:

Here, element i is the adjacent element across the element boundary side Γe,k with unit normal ne,k, i.e., the k th side out of ne,int of element e. This makes \((D_{\mathbf {n}_{e,k}}\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }})\) the change in density over the element boundary Γe,k in the direction of the unit normal ne,k, which in turn means that the internal boundary consists of all internal element boundaries in the FE mesh over which the design density changes. Note that the 2D design implies \(D_{\mathbf {n}_{e,k}}\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }}=0\) for directions ne,k parallel to the extrusion direction, i.e., there is no convection between layers in the extrusion direction. The stiffness contribution can now be written as:

This formulation means that there is a contribution to the convection effect from anywhere the design is varying spatially. The maximal local contribution is obtained if two adjacent elements have maximal difference in design density, which occur in a perfect black-and-white solution. The concept of assuming black-and-white solutions is not controversial, since the penalty term in the objective function will ensure that black-and-white solutions appear. To achieve a differentiable absolute value function, a smooth approximation is used such that

The factor 1/2 in (10) appears since each element will be accounted for twice, from both sides of the internal boundary. To distinguish between the external and internal convections, the contribution from the internal convection is set to 0 if Γe,k ∩ ∂Ω≠∅. A similar approximation as in (10) also applies for the contribution to the load vector f.

The Lp norm approximation in (7) depends on the discrete case on the unknown nodal temperature vector t, which is completely described by the solution tp to the state problem (8), via (9). Assuming equal-sized elements, the discrete version of the objective function (7) now reads:

where [⋅]i denotes the i th component of the element nodal temperature vector te, and ne is the number of nodes of element e. The discrete optimization problem becomes:

where ve is the volume of element e and γmin,γmax ∈ [0,1] are the minimum and maximum fractions of the total domain volume |Ω| that the solid region can occupy, meaning that the volume fraction of the final structure can be in between γmin and γmax. Finally, Ωp is a part of the domain where it has to be material.

5 Numerical examples

The problem (\(\mathbb {P}\)) is solved in Matlab R2017a, using the first order solver fmincon and adjoint sensitivity analysis. The state and adjoint problems are solved with the Matlab built-in preconditioned conjugate gradient solver pcg, using the options maxit= 1000, M1= L and M2= LT for both problems, and the stopping tolerance tol= 1 × 10− 11 for the state problem and tol= 1 × 10− 7 for the adjoint problem. The pre-conditioner L is obtained through a modified incomplete Cholesky factorization of Kp, via the Matlab command ichol. Additionally, the adjoint solution from the previous design step is used as an initial guess when solving the adjoint problem. The FE implementation is based on Liu and Tovar (2014) and the periodic boundary conditions are implemented following Xia and Breitkopf (2015).

5.1 First example

As a first example, the geometry in Fig. 3 is considered. It is a cutout part from a simplified guide vane in a gas turbine, reshaped into a rectangular cuboid in Fig. 4, with dimensions 18 × 36 × 36 mm and a mesh consisting of 60 × 120 × 120 eight-noded, trilinear elements.

The thermal conductivities are ks = 25 m− 1 K− 1 and kf = 10− 9 W m− 1 K− 1, heat the transfer coefficients α0 = β = 250 W m− 2 K− 1, the ambient temperature T∞ = 1000 ∘C, the cooling fluid temperature TC = 400 ∘C, and the penalty factors ψ = 3 in (5), κ = 0.5 in (7) and λ = 5 × 105 in (11). The density filter radius is R = 0.6 mm. The exponent in the Lp norm is set to p = 6. The domain Ωp is defined as the seven outermost layers in the xz-plane on each side of the domain, corresponding to 2.1 mm on each side, and the volume fractions are γmin = 0.4 and γmax = 0.85. The initial guess is a homogeneous design with a total volume fraction of 85%. The stopping criterion for fmincon is either that the normalized step is less than 10− 10 or that the maximum number of iterations is reached, set to 1000.

In Fig. 5a, the 2D design for the first example is shown. Note that it is the filtered (physical) variable \(\hat {\boldsymbol {\rho }}\) that is shown in all design figures. The 3D design is obtained by extruding the 2D design in the out-of-plane direction. Figure 5b is aligned with the left part of Fig. 4, however flipped in the z-direction, showing the outermost layer of the full 3D temperature gradient. The final volume fraction is 83%.

The fluid domain consists of two fairly narrow and vertically oriented separate regions, located right next to Ωp. According to Fig. 5b, the maximum temperature in the structure is found in Ωp and Fig. 5d shows that the maximum temperature is the highest at the end of the optimization run. Also, the Lp norm increases toward the end, but Fig. 5c shows that the objective history is declining and converging. This is due to the penalty term in (7) which is seen to be influential. The early designs were obviously not feasible from a black-and-white perspective.

The four solid islands emerging in the fluid domain (one highlighted with a red arrow) in Fig. 5a are only a couple of elements wide, and therefore partly gray, which makes them undesirable. From a structural integrity point-of-view, it would also be favorable to connect all solid parts in the domain. To achieve this, the filter radius R can of course be changed to allow smaller or larger minimal members in the domain. However, other parameters could also be changed, such as the exponent p in the Lp norm and the penalty factor λ in the objective function, all investigated in Fig. 6. All these designs have a final volume fraction of 85%.

A parameter study of the filter radius R, Lp exponent p and penalty factor λ, visualized for the same cross section as shown in Fig. 5a

It is shown that higher values of all three parameters give more homogeneous and distinct black-and-white designs, primarily by removing smaller members. The smaller members consist largely of gray elements, since the density filter smears out the density values at the boundaries to obtain a smooth transition from solid to fluid. When λ is increased, these gray regions get more unfavorable since they will contribute more to the objective value due to the penalty term in the objective function; and thus, small members will disappear. In black-and-white solutions, the only parts of the domain where there will be gray elements are at the boundaries, due to the filtering process. Since it is the filtered variable \(\tilde {\rho }\) that is penalized in the objective function, the extra penalty term effectively penalizes the length of the internal boundary, since the number of gray elements is proportional to the length of the boundary. Also, less care is taken to minimize the maximum temperature if λ is large and the penalty term is dominating in the objective function. It is a trade-off between having neat black-and-white solutions, which is crucial from both physical and manufacturing perspectives, and only considering the approximated maximum temperature function, which is the intended objective.

By increasing the Lp exponent, the same effect is visible as when increasing λ. This could be due to the explicit presence of \(\hat {\rho }_{e}\), the filtered 3D variable, in the first term of the objective function. A higher exponent value will give a higher contribution to the objective function from gray elements, which would result in fewer gray elements as the exponent value increases. This is also what Fig. 6b shows.

The results should be viewed as conceptual designs only, and further analysis and development needs to be carried out in order to obtain designs ready for manufacturing.

5.2 Second example

As a second example, the guide vane is considered in full, and the cooling channels run in the z-direction as depicted in Fig. 7. There are no periodic boundaries; instead, there is convection on all sides but one, where the temperature is known. The boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 8. Other differences from the first example are that the relative length in the extrusion direction is doubled, the overall dimensions are changed into 36 × 72 × 144 mm, and the passive region is extended around the entire domain with a thickness of 4 elements, which now corresponds to 2.4 mm, since 60 × 120 × 240 elements are used for the discretization. Finally, the filter radius is changed to 1.2 mm. Note that the mesh size in this second example is twice as large as in the first example. It is because the domain size is different in the second example, and the mesh could not be made smaller to compensate for this, without ending up with too many elements to handle for computational effort reasons. Results are found in Fig. 9, and the final volume fraction is 66.6%.

It is noticeable how material that is not fixed to be at the boundary is gathered in the center of the domain. Thus, the best way of keeping the maximum temperature down is to isolate the core of the domain, while cooling the outer frame through convection. The temperature plot shows a large temperature gradient in the fluid part of the domain. The objective function converges properly, but also here a non-negligible effect from the penalty term is seen, which increases the values of the objective function and the evaluated maximum temperature in the domain during the first half of the process. In this second example, no solid islands emerge at all.

6 Conclusions

A model has been proposed for stationary heat transfer TO problems of periodic 3D structures with 2D design, subjected to design-dependent internal convection, with the objective to minimize the maximum temperature, approximated by means of an Lp norm. This could be interesting for manufacturability reasons, since production methods like extrusion could be considered. Furthermore, the method is computationally efficient, since it limits the number of design variables to only one layer of the structure, but at the same time keeps the complexity of a full 3D state problem.

The numerical examples suggest designs where the fluid domain is distributed along the outer edges, as near the external convection boundaries as possible. The Lp norm aggregated temperature is decreased compared to the initial design for the given examples, while the maximum temperature initially drops during the iterations, but increases again, and for the first example even returns to the starting level toward the end of the optimization run. This behavior is most likely due to the penalty term included in the objective function. The penalty level is determined by the penalty factor λ, and higher values decrease the influence from the approximated maximum temperature term in the objective function during the optimization, which consequently might result in suboptimal designs with respect to the maximum temperature.

The choices of the parameter λ and the exponent p in the Lp norm approximation of the maximum temperature affect the solution to a great extent. It is hard to find a sweet spot in between having too much gray in the solution and not considering the intended objective enough. It turns out that this way of penalizing gray elements effectively penalizes the length of the internal boundary.

The results found are somewhat simple designs. The general behavior of this model with the current boundary conditions is, as far as we can see, to make designs that resemble the shape of a thermos. That is, putting an insulating, and cooling, layer of fluid in the outermost part of the domain to protect the inner core from high temperatures. The inclusion of another physics model, for example, fluid flow or a structural model, could yield more complex designs. Future work includes a formulation of a full 3D problem with connections to other physical fields.

7 Replication of results

All information needed to replicate the results found in Section 5 are fully disclosed in this paper. By implementing the relevant equations and choosing the same parameter values as used above, the same results for the problem (\(\mathbb {P}\)) as presented here will be obtained.

References

Ahn S, Cho S (2010) Level set–based topological shape optimization of heat conduction problems considering design-dependent convection boundary. Numer Heat Transfer Part B: Fund 58(5):304–322

Alexandersen J (2011a) Topology optimisation for axisymmetric convection problems. Project report, DTU Department of Mechanical Engineering

Alexandersen J (2011b) Topology optimization for convection problems. Bachelor thesis, DTU, Department of Mechanical Engineering

Bendsøe MP, Sigmund O (2003) Topology optimization, theory, method and applications. Springer, Berlin

Borrvall T, Petersson J (2001) Topology optimization using regularized intermediate density control. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 190(37):4911–4928

Bourdin B (2001) Filters in topology optimization. Numer Methods Eng 50(9):2143–2158

Bruns TE (2007) Topology optimization of convection-dominated, steady-state heat transfer problems. Int J Heat Mass Transf 50(15–16):2859–2873

Dbouk T (2017) A review about the engineering design of optimal heat transfer systems using topology optimization. Appl Therm Eng 112:841–854

Dede EM, Joshi SN, Zhou F (2015) Topology optimization, additive layer manufacturing, and experimental testing of an air-cooled heat sink. J Mech Des 137(11):111403–111403-9

Haertel JHK, Nellis GF (2017) A fully developed flow thermofluid model for topology optimization of 3D-printed air-cooled heat exchangers. Appl Therm Eng 119:10–24

Haertel JHK, Engelbrecht K, Lazarov BS, Sigmund O (2018) Topology optimization of a pseudo 3D thermofluid heat sink model. Int J Heat Mass Transf 121:1073–1088

Holmberg E, Torstenfelt B, Klarbring A (2013) Stress constrained topology optimization. Struct Multidiscip Optim 48(1):33–47

Iga A, Nishiwaki S, Izui K, Yoshimura M (2009) Topology optimization for thermal conductors considering design-dependent effects, including heat conduction and convection. Int J Heat Mass Transf 52(11–12):2721–2732

Liu K, Tovar A (2014) An efficient 3D topology optimization code written in Matlab. Struct Multidiscip Optim 50(6):1175– 1196

Sigmund O, Petersson J (1998) Numerical instabilities in topology optimization: a survey on procedures dealing with checkerboards, mesh-dependencies and local minima. Struct Optim 16(1):68–75

Thellner M, Torstenfelt B (2005) Topology optimization with design-dependent loads using simultaneous shape and topology variation. Appears in: PhD thesis multi-parameter topology optimization in continuum mechanics, Linköping, Studies in Science and Technology Dissertations no 934

Xia L, Breitkopf P (2015) Design of materials using topology optimization and energy-based homogenization approach in Matlab. Struct Multidiscip Optim 52(6):1229–1241

Zhou M, Alexandersen J, Sigmund O, Pedersen CBW (2016) Industrial application of topology optimization for combined conductive and convective heat transfer problems. Struct Multidiscip Optim 54(4):1045–1060

Funding

This work was financed by the Swedish Energy Agency under grant agreement No 2017-001133.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Somanath Nagendra

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lundgren, J., Klarbring, A., Lundgren, JE. et al. Topology optimization of periodic 3D heat transfer problems with 2D design. Struct Multidisc Optim 60, 2295–2303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-019-02319-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00158-019-02319-2