Abstract

The rose window is one of the most representative elements of Gothic art and architecture. In this work we analyze fifteen rose windows from fifteen Gothic cathedrals using fractal geometry. Specifically, we examine the texture and roughness of these rose windows focusing on three factors, their designs, glass areas and solid areas. In this investigation we generate parameters which provide a measure of roughness of the rose windows in order to find out if they show a general non-random fractal pattern. The paper concludes that statistically, there is a characteristic fractal pattern in the solid and glass areas of the rose windows of the Gothic style, but not necessarily in their overall design.

Similar content being viewed by others

Historical Background: Light in the Gothic Cathedral

The Gothic style signaled a veritable revolution in architecture as a result of its technical innovations which challenged the conventional concepts of construction at the time and also changed the manner in which large indoor spaces were conceived. Louis VI, King of France, aspired to rule all of the vast territories which had formed the Carolingian Empire three centuries before. To achieve this aspiration he was assisted in this task by Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis, an advisor with both intelligence and diplomatic skills. In gratitude for the services rendered, Louis VI granted the abbey of Saint-Denis great privileges so that they would have a competitive advantage and be able to hold their prosperous annual fair, which gathered both the faithful and merchants providing major benefits for the abbey. As a result of this, Saint-Denis became the richest Benedictine monastery in France after Cluny. Influenced by the Neoplatonic thoughts which spread amongst scholars of the early twelfth century in the Paris region, Suger was fascinated by light as a means to connecting with God. With this concept as an intellectual guide, Suger inferred that the House of God, the Christian church, had to become a temple of light and even more: “a city bathed in the light of God” (Berger 1906; Panofsky 1970). In order to achieve this ideal, it was necessary to modify and improve the construction system of the great Romanesque churches. That is, it was imperative to remove some walls and tear others from top to bottom in order to place large windows in them which would capture the sunlight. The name of the architect who found the solution to Suger’s problem is unknown. Perhaps it was the master builder who directed the construction of the Romanesque structure in the abbey of Saint-Denis. Regardless, shortly before finishing this work, Suger ordered the following inscription to be places, in Latin verses on the main door of the abbey church. “Portarum quisquis attolere quaeris honorem, Aurum nec sumptus, operis mirare laborem. Nobile claret opus, sed opus quod nobile claret, Clarificet mentes, ut eant per lumina vera, Ad verum lumen, ubi Christus jaunua vera. Quale sit intus in his determinat aurea porta”Footnote 1 (Grosse 2004; Panofsky 1970).

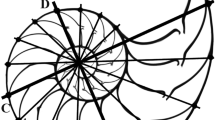

The large windows that could be opened by merging the pointed arch with the ribbed groin vault, supported by buttresses and flying buttresses, made it possible to add spectacular expanses of stained glass through which filtered sunlight could pour into the naves of the cathedrals and give them a new meaning and character. As a result of this, from the thirteenth century onwards, and especially during the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, glassmakers had an increasingly important role in the general context of the plastic arts. This technique was used in every opening of the cathedral, thus incorporating iconographic representations which enhanced the Christian connotations and messages. In most of the main façades of Gothic cathedrals, this artist practice was represented in a unique way. The most important and unique rose window in this part of the cathedral is sometimes referred to as “the eye of God”. Its fretwork circular shape with a mainly radial tracery, and its complex geometry, have made this element one of the most representative objects in Gothic art (Fig. 1). For these reasons, in this paper we will analyze the rose windows of 15 cathedrals—Amiens, Bourges, Burgos, Chartres, Strasbourg, Laon, León, Mallorca, Milan, Orvieto, Paris, Poitiers, Reims, Sens and Troyes—which were built between the 11th and 14th centuries. These fifteen are amongst the most representative of all Gothic cathedrals and their rose windows are probably the most well documented. Using techniques derived from fractal geometry, in this paper we examine the texture and roughness of these rose windows taking into account their designs, their glass areas and their solid areas. Knowing that the main orthographic projections (floor plan, main elevation and cross section) of the French Gothic cathedrals follow a fractal pattern (Samper and Herrera 2014), we want to find out if these rose windows also have a characteristic fractal pattern, or pattern of roughness.

On the left, a modified image of the graphic composition of the Laon’s Cathedral rose window (King 1858. pp. 238). On the right, an original picture of the main elevation

Mathematical Background: Fractal Parameter

As a summary, and by way of conceptual and intuitive explanation in order to clarify the technique which we will introduce next, we argue that the roughness of an object, whether or not it is a fractal object, is geometrically expressed as “its space-filling ability”. This space-filling ability is measured by so-called “fractal parameters”. As explained later in this section, fractal parameters are generated through extrapolated calculations of the theoretical geometric measures of roughness in fractal objects; and these theoretical measures are the different geometric dimensions of fractals. Broadly speaking, roughness is the spatial infiltration behavior of an object across several scales, and a fractal parameter is a value that provides a measure of this infiltration, stating how much that object seems to fill the space as we use finer and finer scales.

This geometric concept is applied in several scientific fields. For example, in medicine, when considering neuronal networks and their pathologies; in electronics, when considering the physical behavior of circuits on smaller manufacturing scales; in chemistry, when obtaining different properties of substances depending on their roughness (Kiselev et al. 2003). This concept is also used in architecture, when seeking evidence of the objective influence between buildings designed by renowned architects, or in order to obtain mathematical evidence with regard to whether or not certain important architects respected the compositional continuity of the artificial or natural environment in which their design was intended to be constructed (Bechhoefer and Bovill 1994; Batty and Longley 1997; Hammer 2006; Sala 2006; Joye 2007; Rian and Park 2007; Bovill 2008; Ostwald 2001; Ostwald et al. 2008; Ostwald and Vaughan 2009; Vaughan and Ostwald 2009, 2011).

In this particular case of study, the field is architecture and the objects considered are architectural designs (which are not fractal objects), and thus we will apply a geometric calculation technique to them in order to generate their fractal parameters, a process which we will explain next. The process can be summarized as follows. Firstly, the elements to be considered are drawn precisely. In this paper we have made three drawings for each rose window, the first shows the design lines; the second highlights the solid areas—made of stone and lead—and the third highlights the glass areas (Fig. 2). Next, and for each of these drawings, we apply a first square mesh made up of squares with a certain edge length. Then we calculate the number of mesh cells intersecting the lines which make up the drawing. Then we apply a second square mesh made up of squares with an edge length which is half of the former edge length, and we calculate again the number of cells intersecting the lines which make up the drawing (that is, the number of cells which contain architectural graphic information). These steps are repeated twice more, until we apply a square mesh with an edge length which is sixteen times smaller than the first. Finally, with all these regions of different scales into which the architectural structure has infiltrated, we undertake the calculation which generates the fractal parameter. As we will see later, this final calculation of the structure’s roughness parameter is given by the geometric theory about the dimensions of fractal objects.

Finally, with all the data generated for the drawings (three parameters for each rose window), we make a robust statistical study of the obtained values. Therefore, the geometric results thus achieved are not subjective and they can be expressed in architectural and geometric language, as we will state in the conclusions of this paper.

Fractal Dimension Theory

This sub-section includes a technical description and references required to fully understand the work which is presented in this paper. In this subsection we summarize the dimensions T(M), \(D\left( M \right)\), \(\bar{F} \left( M \right)\), F(M), H(M), S(M) of the fractal objects M; and some of their properties. This is the theoretical basis from which the ideas for generating the fractal parameters P s (M) arise. First, we will establish a few basic notions. More detailed mathematical references and demonstrations of these are available (Falconer 1990, 1997; Edgar 1998).

In Fractal Geometry we can consider two objects (M, N) such that:

(M is homothetic to N with a homothety h r of ratio r) where g i (N) is a displacement of N—in (1) the union is disjoint. We say that M has an homothetic structure and its homothetic dimension is:

Homothetic objects are particular cases of self-similar objects. Let M be a bounded non-empty object of the Euclidean space A n, such that \(M = \mathop \coprod \nolimits_{i = 1 }^{i = m} S_{i} \left( M \right)\), where S i is a contractive similarity, i.e. \(S_{i} : A^{n} \to A^{n}\) such that ∀(x, y) ∊ A n × A n ⇒ d(S i (x), S i (y)) = k i d(x, y) with 0 < k i < 1. Then M is called a self-similar object, and its self-similarity dimension is the value S(M) such that \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{i = m} {k_{i}^{S(M)} = 1}.\) If a self-similar object M is a homothetic object, then S(M) = H(M). Besides, the objects M of space A n have their topological dimension T(M), where T(M) = 1, 2 or 3 if M is a line, a surface or a three-dimensional body, respectively.

Even though M is self-similar, if S(M) = T(M) we say that M is a non-fractal self-similar object. But when M is self-similar and also S(M) ≠ T(M), then we say that the self-similar object M is fractal. However, objects M in general do not have a homothetic structure nor a self-similar structure; therefore, they do not have a homothetic dimension H(M) nor a self-similarity dimension S(M). In spite of that, there is a generalization of the self-similarity dimension S(M) which is called Hausdorff-Besicovich dimension, noted as D(M). If M, either with or without homothetic or self-similar structure, verifies that D(M) ≠ T(M), then M is a fractal object.

The definition of D(M) uses geometric-mathematical concepts which fall outside the purpose of this paper. Intuitively we can say that an object is a fractal when in an infinite number of its points it does not have tangent space, or to put it more colloquially, it has an infinite number of points where it seems to be fractured. In any case, since the calculation of D(M) falls out from the scope of this paper, we consider another value \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) which is an upper bound of \(D\left( M \right)\). This bound, \(\bar{F}\left( M \right) \ge D\left( M \right)\), is called Minkowski-Bouligand dimension of M, also called upper fractal dimension of M. The object M may or may not be a fractal object, but, regardless of this condition, \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) is a measure of its irregularity, its space-filling-ability or roughness.

There is a theorem that states:

where s m is the number of δ-mesh cubes of A n, that intersect M, with \(\delta = {\raise0.7ex\hbox{$1$} \!\mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {1 {2^{m} }}}\right.\kern-0pt} \!\lower0.7ex\hbox{${2^{m} }$}}\).

For this reason, \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) is also called the upper box-counting fractal dimension. If \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) is equal to \(\mathop {\lim \inf }\nolimits_{m \to \infty } \frac{{ln \left( {s_{m} } \right)}}{{ln \left( {2^{m} } \right)}}\), then \(\mathop {\lim }\nolimits_{m \to \infty } \frac{{\ln \left( {s_{m} } \right)}}{{\ln \left( {2^{m} } \right)}} = F\left( M \right)\) exists, and \(\bar{F}\left( M \right) = F\left( M \right)\). This limit F(M), if it exists, is called fractal dimension of M or box-counting fractal dimension of M.

In Falconer (1990) we find that: (1) \(T\left( M \right) \le D\left( M \right) \le \bar{F}\left( M \right) \le n\). (2) If M is a self-similar object, then \(D\left( M \right) = F\left( M \right) = S\left( M \right)\).

Limit (3) is a theoretical limit of a geometric object M; however, in real cases such as urban plots, the theoretical limit (3) is always substituted by a similar finite calculation. This similar calculation generates a parameter which we will call fractal parameter P(M), and which also offers a roughness measure of M.

Fractal Parameter and Method

After setting out the \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) theory in the former subsection, now we will explain how to generate the fractal parameters P(M).

Architectural structures M are not fractal objects, however we can consider their unevenness, which determines their space-filling ability (that is, their level of roughness), and we can generate a parameter for those non-fractal objects. Since the rose window’s design M is a non-fractal real object, the parameter thus generated cannot be the theoretical value D(M) or \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\). The architectural composition M, despite showing repetitions in some scales, does not really have a homothetic structure nor a self-similar structure. Therefore, we will extrapolate the theoretical calculations of \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) and S(M) in order to generate parameters which provide measures of roughness. We will call these parameters P s (M) and P r (M).

Parameter P s (M) will provide a measure of roughness without taking into account the self-similarity aspect [this measure will come directly from the theoretical process described in (3) for \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\)]; and parameter P r (M) will provide a measure of roughness taking into account the self-similarity aspect. Since these parameters come from theoretical extrapolations which are not applicable to the real structure M, they cannot be separated from the generation process. Consequently, any study which is made with such parameters must fulfill two conditions: firstly, the parameter-generation process must be clearly defined, and secondly, the results of such study are not the parameters themselves but the general conclusions drawn from the parameters, regardless of their specific values.

Summary of the Fractal Parameter’s Generation Process

The first step of our investigation was to collect as many graphic documents as possible from all the rose windows being studied (Fig. 1). The main information sources used were the respective archdioceses of the cathedrals, historical archives (King 1858), universities and private or public companies and entities. Secondly, we have redrawn all documents collected in order to attain the highest level of objectivity, homogeneous graphic display criteria and the same level of detail (Figs. 2, 3). This redrawing is absolutely necessary, since the documents collected consist of drawings with shadows, stains, colors, defects and freehand lines. Because all graphic documents show “noise”, we had to recreate each and every one of the drawings which appear in this paper and were used in the analysis. We have strictly followed precise drawing lines, highlighting the lines which best represent the geometry of all rosette designs (Ostwald and Vaughan 2012, 2013; Vaughan and Ostwald 2014). Since rose windows are openings through which light enters the cathedral, we have made two additional variants of each drawing (apart from the one showing the design lines) showing the solid areas (Fig. 2). Therefore, this paper examines 45 drawings (3 drawings for each of the 15 rose windows).

The process to generate P s (M) through calculations with self-created software is summarized as follows:

-

1.

Given the architectural design M, first we generate its design in AutoCad vector format, using black color and line width \(\sim 0.00 \,mm\). From this AutoCad format we obtain the pdf vector format.

-

2.

From the pdf vector format we generate a black-and-white digital bitmap file, sized 1024 × v pixels, showing the architectural design with its size adjusted to full width and height.

-

3.

P s (M)—Using self-created software, we calculate the fractal parameter P s (M) based on the slope on the last point of a continuous graph ln–ln. In the following sections we explain which continuous graph we are talking about and which calculations are made.

The reason we have created special software is twofold: firstly, we will have total control of the calculations and so we will ensure they are correct. Secondly, commercial software like Benoit 1.31 de TruSotf Int’I Inc does not use the slope on the last point of the continuous graph ln–ln.

Then, if we change step 3 above and instead we use the calculation for the slope of the regression line corresponding to the discrete set of points, then we obtain another fractal parameter which we will call P r (M):

-

3.

P r (M)—using our self-created software, we calculate the fractal parameter P r (M) based on the slope of the regression line corresponding to the discrete set of points in the graph ln–ln; and for this calculation we use square meshes, the finest mesh having 4 × 4 pixel squares, and the coarsest mesh having 32 × 32 pixel squares.

We would like to point out that, even though the different calculation methods may be subject to certain variation (Ostwald 2013) and the value of the fractal parameter (of non-fractal objects) depends on the method being used and also on the level of graphic detail of the drawing (Ostwald and Ediz 2015), we have been able to draw conclusions from our method because they are based on the global statistic correlations between all the fractal parameters obtained here.

Practical Example Applied to Rosette Troyes’ Cathedral

In this sub-section we have calculated the fractal parameter of the Troyes’ Cathedral Rosette based on the theory and the summary of the fractal parameter’s generation process explained in the previous sub-section (Fig. 4).

Since N is a pixelated digital image file, the calculation process to generate P(M) will have a finite number of steps. The finest mesh used to generate P(M) is a 4 × 4 pixel square mesh, because 4 = 2n gives the finest mesh which is similar to the theoretical meshes for the theoretical calculation of \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\) (Falconer 1997). This is true because the 4 × 4 pixel squares have inside points and border points. Therefore, in order to calculate P(M) we will use four meshes the squares of which are 4, 8, 16 and 32 pixels in length, respectively. The reason to use four meshes is that, as we will see later, P(M) is generated with the slope of a function of a continuous graph ln–ln. Using the classical interpolation methods, 4 points of a function are enough to find a good approximation of that slope. And we should not use more than 4 interpolation points because of the well-known Runge Phenomenon in numerical calculation. Then, our software generates a square mesh, which we have called g 5, consisting of 32 × h 5 square boxes with an edge dimension a 5 = 1024 × 2−5 = 32 pixels. Then we apply that mesh on the image of N and we calculate ln(s 5), where s 5 is the number of boxes of g 5 which have black pixels. Then we repeat the process with the other square meshes g 6, g 7 and g 8 having \(64 \times h_{6}\), 128 × h 7, 256 × h 8 square boxes, respectively. The edge dimensions are a 6 = 1024 × 2−6 = 16, a 7 = 1024 × 2−7 = 8 and a 8 = 1024 × 2−8 = 4, respectively. Then we calculate ln(s 6), ln(s 7), and ln(s 8), where s 6, s 7 and s 8 are the number of boxes with black pixels in each mesh g 6, g 7 and g 8, respectively. For example, Fig. 4 shows the data corresponding to: \(\left( {h_{5} , h_{6} , h_{7} , h_{8} } \right) = \left( {32, 64, 128, 256} \right), \left( {s_{5} , s_{6} , s_{7} , s_{8} } \right) = \left( {984, 3182, 9259, 24426} \right)\). As a result of the above mentioned process we obtain the coordinates of four points \(\left( {\ln \left( {2^{5} } \right), \ln \left( {s_{5} } \right)} \right)\), \(\left( {\ln \left( {2^{6} } \right), \ln \left( {s_{6} } \right)} \right)\), \(\left( {\ln \left( {2^{7} } \right), \ln \left( {s_{7} } \right)} \right)\), \(\left( {\ln \left( {2^{8} } \right), \ln \left( {s_{8} } \right)} \right)\), in a graph ln–ln shown in the center of Fig. 4.

Parameter P s (M)

Now, our software calculates the slope of the continuous graph ln–ln on the fourth point \(\left( {\ln \left( {2^{8} } \right), \ln \left( {s_{8} } \right)} \right)\). Such slope is an extrapolation of the process used to calculate the theoretical limit of the upper fractal dimension \(\bar{F}\left( M \right)\). To confirm that the preceding claim is true, you can consider 4 and use l’Hopital’s rule. In order to calculate that slope, the software implements the classical four-point formula 5, where h = ln2 and y i = ln(s 5+i ). The final result y′3 given by our software is the fractal parameter P s (M). In the example, the fractal parameter is \(\frac{1}{6\ln 2}\left( { - 2\ln \left( {984} \right) + 9\ln \left( {3182} \right) - 18\ln \left( {9259} \right) + 11\ln \left( {24426} \right)} \right) \approx 1.33\).

Parameter P r (M)

We have explained that the fractal parameter P s (M) is generated by means of the slope in the fourth point of the continuous graph ln–ln. However, in the theoretical case of fractal self-similar objects such a graph is a straight line. Therefore, if we generate a fractal parameter under the hypothesis of self-similarity, then we can use the slope of the regression line corresponding to the discrete set of the four points belonging the graph ln–ln. So, the calculation is the quotient of the covariances \(\frac{{\sigma_{xy} }}{{\sigma_{xx} }}\) where:

This fractal parameter will be called P r (M). In the case of the rose window displayed in Fig. 4, we have P r (M) ≈ 1.55.

Discussion

The Fractal Pattern of the Rose Windows Design

After the study of the design of the fifteen gothic rosettes, we have calculated the mean \(m_{{D_{s} }} \approx 1.369\) of their fractal parameters P s (M) and the standard deviation \(\sigma_{{D_{s} }} \approx 0.187\). Therefore, the Pearson’s coefficient of variation of P s (M) is \(CV_{{D_{s} }} = 14\,\%\). In general, when the Pearson’s coefficient of variation is under 25 % it is considered that there is little scattering around the mean, or that the mean is representative. As a result, the mean is representative. In order to determine the probability of the mean \(m_{{D_{s} }}\) being a non-random result, we have applied Pearson’s Chi squared test with 19 degrees of freedom in the following two-way table, Table 2, where \(I_{1} = \left[ {1.01, 1.05} \right],\, I_{2} = \left[ {1.06, 1.10} \right], \ldots , I_{19} = \left[ {1.91, 1.95} \right], I_{20} = \left[ {1.96, 2} \right]\); and the result is χ 2 ≈ 13.684.

In conclusion this table is a non-random table with probability \(P_{{D_{s} }} = 0.198\, \ll 0.998\). This probability is very low, consequently the mean \(m_{{D_{s} }}\) is a random result. But, despite the size of Table 2, which has 19 degrees of freedom, some of the 40 expected frequencies are less than 5. Therefore, one might think that we have taken the wrong decision using Pearson’s Chi squared test. In order to dispel any doubts, we apply Fisher-Irwin’s exact test to the 1855967520 possible matrices. By calculation, we find that the value P cutoff of conditional probability for this table’s matrix is \(P_{cutoff} = \frac{{15!285!\left( {15!} \right)^{20} }}{{300!\left( {0!} \right)^{8} \left( {1!} \right)^{9} \left( {2!} \right)^{3} \left( {15!} \right)^{8} \left( {14!} \right)^{9} \left( {13!} \right)^{3} }} \approx 5.788725 \times 10^{ - 9}\). The number n cutoff of matrices having conditional probability P value,i ≤ P cutoff is n cutoff = 1820641656. Finally, the two-side P value of the test is \(P_{value} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{{n_{cutoff} }} P_{value,i} \approx 0.741525 = P_{{D_{s} }}\). In conclusion, using the exact test, this table is a non-random table with probability \(P_{{D_{s} }} = 0.741525 \gg 0.05\). This probability is very high, consequently the mean \(m_{{D_{s} }}\) is a random result. From this we cannot conclude that the rose windows show a fractal pattern. If the mean for s or r parameters is not representative or is a random result, the geometry of the configuration does not have a geometric pattern; the existence of the pattern must be independent of the type of parameter used, giving a numerical value for the roughness of the geometric configuration.

The Fractal Pattern of the Solid Areas in the Rose Windows

Applying the same method used in the previous subsection, we have analyzed the configuration of the solid areas of the rose windows (Fig. 6). Using Table 1, we have calculated the mean \(m_{{S_{s} }} \approx 1.768\) and the standard deviation \(\sigma_{{S_{s} }} \approx 0.106\) of the parameters PS(M). Therefore, the Pearson’s coefficient of variation is \(CV_{{S_{s} }} = 6\;\%\). As a result, the mean is very representative. If then we apply Pearson’s Chi square test with 19 degrees of freedom to the data in Table 3 (the two-way table of s parameters for the solid areas)—as we did with Table 2—, the result is χ 2 ≈ 44.561. The table is a non-random table with probability \(P_{{S_{s} }} \ge 0.998\), so the mean \(m_{{S_{s} }}\) is a non-random result with a very high probability. We can also use Fisher-Irwin’s exact test, the result of which is \(P_{cutoff} = \frac{{15!285!\left( {15!} \right)^{20} }}{{300!\left( {0!} \right)^{13} \left( {1!} \right)^{3} \left( {2!} \right)^{2} \left( {4!} \right)^{2} \left( {15!} \right)^{13} \left( {14!} \right)^{3} \left( {13!} \right)^{2} \left( {11!} \right)^{2} }} \approx 9.018023 \times 10^{ - 12}\),\(n_{cutoff} = 250220824\) and \(P_{value} = \mathop \sum \nolimits_{i = 1}^{{n_{cutoff} }} P_{value,i} \approx 0.000742 = P_{{S_{s} }} \ll 0.01\), so the mean \(m_{{S_{s} }}\) is a non-random result with a very high probability.

The analysis results of the parameters P r (M) for the solid areas are, \(m_{{S_{r} }} \approx 1.722\) (Mean), \(\sigma_{{S_{r} }} \approx 0.082\) (Standard Deviation) and \(CV_{{S_{r} }} = 5\;\%\) (Pearson’s Coefficient of Variation). The mean is very representative and if we apply the Chi square test to the data in Table 4 (the two-way table of r parameters for the solid areas), the result is χ 2 ≈ 52.5982 and \(P_{{S_{r} }} \ge 0.998\), so the mean \(m_{{S_{r} }}\) is a non-random result. The Fisher-Irwin’s exact test for Table 4 generates the result of P cutoff ≈ 2.834236 × 10−12, n cutoff = 132157864 and \(P_{value} \approx 0.000133 = P_{{S_{r} }} \ll 0.01\), so the mean \(m_{{S_{r} }}\) is a non-random result. Thus, the means of the parameters s and r are a non-random results and they are very representative. Therefore, the solid areas of the rose windows follow a fractal pattern.

The Fractal Pattern of the Glass Areas in the Rose Windows

Applying the same method used in the previous subsection, we have analyzed the configuration of the glass areas (Fig. 7). Using Table 1, we have calculated the mean \(m_{{L_{s} }} \approx 1.865\) and the standard deviation \(\sigma_{{L_{s} }} \approx 0.077\) of the parameters PS(M). Therefore, the Pearson’s coefficient of variation is \(CV_{{L_{s} }} = 4\;\%\). As a result, the mean is very representative. If we apply Pearson’s Chi square test with 19 degrees of freedom to the data in Table 5 (the two-way table of s parameters for the glass areas) the result is \(\chi^{2} \approx 52.982\). The table is a non-random table with probability \(P_{{L_{s} }} \ge 0.998\), so the mean \(m_{{L_{s} }}\) is a non-random result with a very high probability. Using Fisher-Irwin’s exact test, the result of which is P cutoff ≈ 1.910485 × 10−12, n cutoff = 112801120 and \(P_{value} \approx 0.000048 = P_{{L_{s} }} \ll 0.01\), the mean \(m_{{L_{s} }}\) is a non-random result with a very high probability.

The results of the analysis of the parameters P r (M) for the glass areas are \(m_{{L_{r} }} \approx 1.820\) (mean), \(\sigma_{{L_{r} }} \approx 0.094\) (standard deviation) and \(CV_{{L_{r} }} = 5\%\) (Pearson’s coefficient of variation). The mean is very representative and if we apply the Chi square test to the data in Table 6 (the two-way table of r parameters for the glass areas), the result is χ 2 ≈ 45.614 and \(P_{{L_{r} }} \ge 0.998\), so the mean \(m_{{L_{r} }}\) is a non-random result. Again we apply Fisher-Irwin’s exact test, the result of which is P cutoff ≈ 2.605207 × 10−12, \(n_{cutoff} = 125181064\) and \(P_{value} \approx 0.000115 = P_{{L_{r} }} \ll 0.01\), so the mean \(m_{{L_{r} }}\) a non-random result. The means of the parameters s and r are a non-random results and they are very representative. Therefore, the glass areas of the rose windows follow a fractal pattern.

Conclusion

Using the strictest possible interpretation of the statistical criteria, a fractal pattern exists if and only if there is pattern in parameter P r and P s simultaneously. Therefore, using the fractal geometric parameterization, it has been proven that the rose windows designs do not follow any characteristic roughness pattern (Table 7). With all these results, we can conclude that each of these rose windows was designed according to the particular stylistic approach of the corresponding architect, the construction budget and, finally, the architectural composition of the main elevation. However, if we analyze the techniques which glassmakers and stonemasons applied to the geometry of the solid and glass surfaces, we find more interesting results. After analyzing the solid and glass areas of the rose windows we do find a characteristic roughness pattern because there is a fractal pattern in both types of parameters (Table 7). This means that the rose windows were designed with the same roughness model for solid areas and glass areas. This results allows us to conclude that there is a characteristic fractal pattern not only in the Gothic structures (floor plan, elevation and cross-section) (Samper and Herrera 2014), but also in the rose windows (solid areas and glass areas), which are one of the most representative elements of the Gothic style.

Notes

“All you who seek to honor these doors, marvel not at the gold and expense but at the craftsmanship of the work. The noble work is bright, but, being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through the lights to the true light, where Christ is the true door.”

References

Batty, M. and P. Longley, 1997. The Fractal City. Architectural Design 67 (9): 74–83.

Bechhoefer, W. and C. Bovill, 1994. Fractal Analysis of Traditional Housing in Amasya, Turkey. In: Proceedings of the fourth Conference of the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments. Berkeley: International Association for the Study of the Traditional Environment.

Berger, É. 1906. Les Aventures de la reine Aliénor. Historie et Légende. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres. Paris: Alphonse Picard et fils, Éditeurs.

Bovill, C. 2008. The Doric Order as a Fractal. Nexus Network Journal 10 (2): 283–290.

Edgar, G. 1998. Integral, Probability, and Fractal Measures. New York: Springer.

Falconer, K. 1990. Fractal Geometry, Mathematical Foundations and Applications. Chichester: John Willey.

Falconer, K. 1997. Techniques in Fractal Geometry. Chichester: John Willey.

Grosse, R. 2004. Suger, Personnage Complexe par Jean Dufour dans Suger en Question: regards Croisés sur Saint-Denis. Oldenbourg: Oldenbourg Editor.

Hammer, J. 2006. From Fractal Geometry to Fractured Architecture: The Federation Square of Melbourne. Mathematical Intelligencer 28 (4): 44–48.

Joye, Y. 2007. Fractal Architecture Could be Good for you. Nexus Network Journal 9 (2): 311–320.

King, T. 1858. An Original Architectural Plate from: The study-book of Mediaeval Architecture and Art. Working Drawings of the Principal Monuments of the Middles ages. London: Bell and Daldy.

Kiselev, V., K. Hahn, and D. Auer, 2003. Is the Brain Cortex a fractal? Neuroimage 20 (3): 1765–1774.

Ostwald, M., J. Vaughan, and S. Chalup, 2008. A Computational Analysis of Fractal Dimensions in the Architecture of Eileen Gray. In: Biological Processes and Computation, ACADIA 08: 256–263.

Ostwald, M. J. 2001. Fractal Architecture: Late 20th Century Connections between Architecture and Fractal Geometry. Nexus Network Journal 3 (1): 73–84.

Ostwald, M. J. and J. Vaughan, 2009. Calculating Visual Complexity in Peter Eisenman’s Architecture: a Computational Fractal Analysis of Five Houses (1968-1976). In: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Conference on Computer Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia. CAADRIA 2009: 75–84

Ostwald, M. J. and J. Vaughan, 2012. Significant Lines: Measuring and Representing Architecture for Computational Analysis. In: 46th Annual Conference of the Architectural Science Association, ANZAScA 2012: 50–60.

Ostwald, M. J. and J. Vaughan, 2013. Representing Architecture for Fractal Analysis: a Framework for Identifying Significant Lines. Architectural Science Review 56 (3): 242–251.

Ostwald, M. J. 2013. The Fractal Analysis of Architecture: Calibrating the Box-Counting Method Using Scaling Coefficient and Grid Disposition Variables. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 40 (4): 644–663.

Ostwald, M. J. and Ö. Ediz, 2015. Measuring Form, Ornament and Materiality in Sinan’s Kiliç Ali Pasa Mosque: an Analysis Using Fractal Dimensions. Nexus Network Journal 17(1): 1:5–22.

Panofsky, E. 1970. Architecture Gothique et Pensée Scolastique. Paris: Les éditions de Minuit.

Rian, I. and J. Park, 2007. Fractal Geometry as the Synthesis of Hindu Cosmology in Kandariya Mahadev Temple, Khajuraho. Building and Environment 42 (12): 4093–4107.

Sala, N. 2006. Fractal Geometry and Architecture: Some Interesting Connections. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment 86: 163–173.

Samper, A. and B. Herrera, 2014. The Fractal Pattern of the French Gothic Cathedrals. Nexus Network Journal 16 (2): 251–271.

Vaughan, J. and M. J. Ostwald, 2009. A Quantitative Comparison Between the Formal Complexity of Le Corbusier’s Pre-Modern (1905-1912) and Early Modern (1922-1928) Architecture. Design Principles and Practices: An international journal 3 (4): 359–372.

Vaughan, J. and M. J. Ostwald 2011. The Relationship Between the Fractal Dimension of Plans and Elevations in the Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright: Comparing the Prairie Style, Textile Block and Usonian Periods. Architecture Science Research: ArS 4: 21–44.

Vaughan, J. and M. J. Ostwald, 2014. Measuring the Significance of Façade Transparency in Australian Regionalist Architecture: A computational Analysis of 10 Designs by Glenn Murcutt. Architectural Science Review 57 (4): 249–259.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Samper, A., Herrera, B. A Study of the Roughness of Gothic Rose Windows. Nexus Netw J 18, 397–417 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-015-0264-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-015-0264-6