Abstract

The present study aimed at assessing the validity and accuracy of the new official Bulgarian list of seafood trade names in compliance with EU requirements, and the list evolution and adherence to the Bulgarian market trends. The new list consists of 88 commercial designations (CD) associated with 81 scientific names (SN) provided as 72 species, 8 genera and 1 family mostly belonging to the fish category (86.4%, SN = 70) . The list analysis highlighted the presence of 14 invalid SN (17.3%), with an obsolete classification. In terms of adherence to the Bulgarian market’s trend the inclusion of 51 new SN reflecting fishing data in total, both from inland waters and along the Black Sea coast was pointed out. However, 44 SN relating to commercially relevant species and currently available at purchase were deleted. In terms of accuracy, the introduction of SN as family, the significant reduction of CDs and the use of vague CDs lead the list to distance itself from the one name-one fish conception, proposed at international level, as ideal approach for unambiguous product identification by the consumer. To conclude, the analysis shows a clear will of the national Bulgarian Legislator to enhance local fisheries and aquaculture trade. Nevertheless, major issues related to the SN validity and the non-adherence to seafood market trends are highlighting the ineffectiveness of the current list in describing retail seafood products. This emphasizes the urgency to provide a further substantial list revision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Seafood traceability, sustainability and frauds countering represent major inspiring principles of the EU common organisation of the markets in fishery and aquaculture products (CMO), as defined by the Council Regulation EU No. 1379/2013. This regulation integrates with the common marketing standards for unprocessed fishery (Council Regulation EC No. 2406/1996) and the control system of the European Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) as defined in the Council Regulation EC No. 1224/2009 and its Implementing Regulation EU No. 404/2011. All the above-mentioned regulations require fishery and aquaculture products to be identified with a valid scientific name throughout the entire supply chain. Pursuant to the Regulation EC No. 1224/2009, each catch or production batch has also to be associated with mandatory information on:

-

a.

fishing or harvesting area;

-

b.

the type of gear and mesh size and dimension used during the catching;

-

c.

a weight estimation of the lot; and.

-

d.

the FAO alpha-3 code of each species.

The FAO 3-letter code, imposed to monitor and trace the species catches, is directly accessible by the FAO database.Footnote 1 Its presence constitutes an additional informative element in support of both the Food Business Operators (FBOs) and the Competent Authorities (Cas) for monitoring the traceability of the products.

The Regulation EU No. 1379/2013 defines mandatory information for labelling of seafood intended for sale to the final consumer (Article 35). In addition to the indications included in the Regulation EC No. 1224/2009, it requires mandatory information such as:

-

product trade name composed by the commercial designation,

-

scientific name,

-

the date of minimum durability (where appropriate), and

-

the mention of a previous freezing-thawing process.

Furthermore, each Member State is delegated to draw up and update an official list, reporting the commercial designation accepted throughout the country in association with a valid scientific name in accordance with FAO reference databases (Article 37).

In Bulgaria, the first official list was published by the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry within the Ordinance No. 4 of 13.01.2006 (2006). However, based on two recent surveys on the Bulgarian market, the list was found to be ineffective in describing the seafood products marketed at national level in the various retail channels (Tinacci et al. 2018, 2020). Major deficiencies concerned the absence of official commercial designations for:

-

a.

several commercially relevant fish species from the Black Sea and the Bulgarian aquaculture sector,

-

b.

several highly imported species,

-

c.

crustacean and mollusc species, despite the increased consumers’ demand and imports.

Moreover, the use of obsolete scientific names and commercial designation, were highlighted (Tinacci et al. 2018, 2020). In this respect, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry recently issued the Ordinance No. 13 30.11.2021 (2021) on “Terms and conditions for making the first sale of fishing products” which includes the applicative guidelines for Regulation EC No. 1224/2009 and Regulation EC No. 2406/1996, and the new Bulgarian list of seafood commercial designations. Upon the Ordinance publication, the previous list has been abrogated and entirely repealed.

Based on this, the present study aimed at verifying the validity, correctness, and accuracy of the new official list of commercial designations according to the Regulation EU No. 1379/2013 and evaluating its evolution and adherence to the Bulgarian market’s trend.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Descriptive analysis: correctness and validity of the updated list

The structure and correctness of the new Bulgarian official list of seafood commercial designation was analysed according to the model proposed by Tinacci et al. (2019). The listed SN, consisting of one species or genus names, were firstly grouped in 4 taxonomical categories:

-

1.

Fresh water, anadromous and marine fish (Chondrichthyes; Osteichthyes) (F);

-

2.

Crustaceans (C);

-

3.

Mollusc bivalves, cephalopods and gastropods (M);

-

4.

Other organisms (O) (Echinoderms, tunicates animals, Cnidaria, Amphibians).

The SN were checked according to FAO’s official information systemsFootnote 2 and as well as the World Register of Marine SpeciesFootnote 3 (WorMS) that were used as taxonomic authorities. All SN with the associated commercial designations (CD) were counted. The correctness of the FAO alpha-3 codes was assessed by comparing them to those reported on the Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System (ASFIS) (FAO 2022a).

2.2 Adherence to bulgarian market trends

This aspect was evaluated by comparing the SN and commercial denominations (CD) from the list with data from:

-

a.

the outcomes of two previous studies (Tinacci et al. 2018, 2020);

-

b.

the Bulgarian seafood market (Todorov 2020), and

-

c.

market products available at purchase, collected within a three-year monitoring plan (2019–2021) as part of the National Scientific Program funded by Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science.

2.3 List accuracy

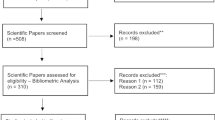

The current list was compared to the previous one (Ordinance No. 4 30.01.2006, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry 2006) to assess both the overall and the categories’ evolution trend in terms of included number of records. The list accuracy was assessed by calculating a species index (SI) corresponding to the ratio of the total number of CD and the number of SN as proposed by Xiong et al. (2016). A second index, the “cumulative species index” (c-SI), was also calculated by dividing the total number of CD with the total number of listed species-specific SN, and then added with the total number of species from the FAO databases for each included genus or family name.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Descriptive analysis: correctness and validity of the updated list

The new Bulgarian list of official seafood designations contains 4 subsections (freshwater fish, anadromous fish, marine fish, other organisms) in which 88 CD are associated with 81 SN (72 species, 8 genera and 1 family). Considering the taxonomical categories assigned in this study, F contributes for 86.4% (n = 70), followed by C (6.2%, n = 5), M (6.2%, n = 5) and O (1.2%; n = 1) (Fig. 1). Overall, this results show that the main attention of the legislator was primarily focused on fish. This could be due to market demands that are less oriented towards other seafood categories (see Sect. 3.2 for more details).

Regarding the correctness and the validity of the SN as referred in the FAO and WorMS databases, 14 SN (17.3%) were misclassified because of obsolete classifications (Table 1). The periodic verification of SN validity is required due to the constant updating in seafood phylogeny research, and is also recommended by the Regulation EU No. 1379/2013 (Tinacci et al. 2019). A regularly revision of the taxonomic classification is even more needed given the evidence collected on the newly published list.

A new element compared to the previous ordinance is the presence of alpha 3-codes listed alongside the individual SNs. Pursuant to Regulation EC No. 1224/2009, FBOs are required to associate the alpha-3 code immediately after sorting each species at catch registration on the vessel. Therefore, the code is on all enclosed documents of the individual lots and available during the first sale of the products. Thus, this information may be included in order to offer FBO an alternative consultation tool to the ASFIS database, which may not be readily consulted by the operators even though it is freely accessible (Tinacci et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the analysis of the alpha-3 codes highlighted a wrong association with 4 species and 3 genera (Table 2).

3.2 Adherence to the bulgarian market trends

An increase of 51 SN in the current list compared to the previous one was observed, including 42 species, 8 genera, and 1 family (Table 3). In general, the species present in the current list reflect fishing data from both inland waters (Danube and inland watersheds) and the Black Sea. In addition, species from aquaculture and restocking activities for recreational fisheries are included (Todorov 2020; FAO 2022b, c). The newly introduced SN mainly refer to freshwater species leading the aquaculture sector. These species are well represented in local catches, and are still playing a significant role in less developed areas bordering the Danube River (Raykov and Triantapyllidis 2015; FAO 2022b, c). There is a massive presence of fish species belonging to the Cyprinidae and Salmonidae family, and some highly valuable species of the Acipenseridae family, widely reported in inland waters at national level (Shivarov 2021). Additionally, marine species of commercial interest at national and local level such as Rapana sp., Atherina sp. or Belone belone and Dicentrachus labrax have been added on the list. This is significantly different to the previous list, as already highlighted by Tinacci et al. (2018, 2020). In general, SN refer to species that are relevant and represented in local fisheries along the Black Sea coast such as: European sprat (Sprattus sprattus), sardine (Sardina pilchardus), Mediterranean horse mackerel (Trachurus mediterraneus), mullet (Mugil sp.), bonito (Sarda sarda), bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix), whiting (Merlangius merlangus) red mullet (Mullus barbatus), turbot (Scophthalmus maxims), gobies (Gobiidae family), piked dogfish (Squalus acanthias), thornback ray (Raja clavata) (Shivarov 2021). This policy update shows the will of the national legislator to include and valorise local fisheries and aquaculture productions. Considering the significant drop in national production in the last 4 years, mainly due to lower production of the main cultured species, makes this even more relevant. Therefore, the policy update is probably an attempt to relaunch the sector by ensuring that the product labelling in compliance with European legislation (Todorov 2020). Nevertheless, despite the introduction of 51 new SN, the overall increase of the total number of SN (n = 81) is just slightly higher than in the previous list (n = 74), which is due to the removal of 44 SN (33 species and 11 genera) from the list (Table 3). Also, the total number of SN is still notably below the number of records listed by other EU Member States (Tinacci et al. 2018). Therefore, the revision of the list is not adhering to the principles of consumer information enunciated by the Regulation EU No. 1379/2017. This is in contrast with the increasing number of species included in the official lists both of other European countries and at international level, as a result of periodic updates.Footnote 4 An example is described for the Italian official list in Tinacci et al. (2019). The gradual expansion of the official list in relation to the increasing variability of supply is crucial to guarantee consumer rights on informed choice, and to encourage informed consumption of fish products.

This aspect was also stressed in a recent study by Paolacci et al. (2021) on the compliance of labels of seafood products to EU legislation. In the study, low attention to traceability and correct labelling was observed in those European countries where consumers are unfamiliar with the appearance of seafood species and are not adequately informed about the variability of seafood. In this sense, a product label showing SN combined with well-known CD is a way to educate consumers regarding conscious purchase.

In fact, with the new Bulgarian list that came into force, FBO are lacking relevant seafood CD. Specifically, the updated list is contradictory to the expansion of the Bulgarian seafood market towards Mediterranean, Atlantic and Pacific species like Clupeids, Scombrids, Gadids and Merluccids (Tinacci et al. 2020). The official deletion of those SN poses a contingent deficiency for marketing imported products such as Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), pollack (Pollachius pollachius), saithe (Pollachius virens) haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), herring (Clupea harengus), bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus), big eye tuna (Thunnus obesus) and chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus). The latter is a widely used alternative to mackerel (Scomber scombrus) in the production of processed and canned products (Tinacci et al. 2018, 2020; Todorov 2020). A summary of relevant species currently available on the Bulgarian market but still not included in both the new and the repealed list shows Table 4.

Overall, the results show a contradiction between the list and the market needs; and the persistent absence of several species with overall high frequency market rates (Salmo salar, Thunnus albacares, Sparus aurata, Gadus chalcogrammus, Merluccius hubbsi (Tinacci et al. 2020). Similar shortcomings were noted in crustaceans and molluscs categories, where the new list includes a paltry number of species with no relevant changes to the previous list and in contrast with current market trends (Tinacci et al. 2018; EUMOFA 2019). In particular, the new list lacks crustaceans mainly imported from India, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Indonesia such as Litopenaeus vannamei, Penaeus monodon, Metapenaeus sp., Penaeus sp. which are of major interest for the local fishery (Gogaladze et al. 2021; Shivarov 2021; FAO 2022b). Also, brown crab (Cancer pagurus) and Norway lobster (Nephrops norvegicus), both widely available on the market, especially at large retail, was deleted from the list. They are imported within the EU and originating from the North Atlantic.

Regarding molluscs, the list does not consider caught and cultured bivalve species such as Chamelea gallina, Donax trunculus, Dreissena sp. as local interest (Klisarova et al. 2020). Few imported species of major market interest from the North Atlantic, Southwest Atlantic and Southeast Pacific such as Mytilus edulis, Mytilus chilensis and Perna canaliculus are mostly available at large retail (authors’ data). The total disappearance of cephalopods is also evident, they were included in the previous list with at least 2 species of local interest (Rossia macrosoma and Sepia officinalis). Thus, the list should be amended by re-entering records of species belonging to the Sepiidae family, and by including new species like Loliginidae, Ommastrephiidae and Octopodidae currently available at retail as fresh, frozen and processed products (authors’ data). Furthermore, Rapana sp., the only gastropod on the new list and previously not mentioned, should be listed as rapa whelk (R. venosa), and one of the most exploited species along the Black Sea coasts (Raykov 2020).

3.3 List accuracy

The approach to be used in the association of CD and SN for providing a clear consumer information has been debated internationally. Ideally, the association of a single CD for each SN would allow the univocal identification of each product (Lowell et al. 2015). According to Xiong et al. (2016), SI = 1 is the most accurate scenario in which a single CD is associated to only one SN, which agrees with “the one species one name” approach proposed by Lowell et al. (2015). As also reported by Tinacci et al. (2019), SI > 1 is suggestive of the association of multiple accepted CD for each SN. On the contrary, SI < 1 indicates the presence of identical CD for different species, even potentially distant. Based on this index of accuracy, the analysis of the previous list (Tinacci et al. 2018) showed an overall high level of accuracy (SI = 1.04) scaled down by the correction applied to calculate the cumulative index (c-SI = 0.22). This is far away from the previously mentioned “one species - one name” approach. The SI and c-SI calculated for the current list shows a notable drop of the c-SI (0.04) and consequently of the list accuracy. This further drop, despite the disappearance of 11 genera that were included in the previous list, is directly linked to the introduction of SN related to Gobiidae, including 1986 accepted species in total, in addition to the species contribution (n = 44) from the above mentioned 8 genus (Vimba sp, Ictiobus sp; Atherina sp, Leander sp., Crangon sp., Unio sp. - valid name Vulsella sp; Anodonta sp., Rapana sp.). This suggests that the introduction of an entire Family as SN is not advisable and strongly opposes to the principles of EU regulation of a clear product identification for the final consumer. In this perspective, particular attention should be paid to the attribution of CD in association with individual SN. By analysing the CD of the current list together with market data from Tinacci et al. (2020), and the data collected within a 3-year monitoring of the National Scientific Program, a frequent use of generic and vague names was observed (Tables 3, 4). Several authors defined them as “umbrella” terms, and linked their use to the potential enhancement of substitutions and intentional frauds (Xiong et al. 2016; Cawthorn et al. 2018, 2021; Tinacci et al. 2019).

In this study, the use of umbrella terms was mostly found as associated with species belonging to Gadiformes (Gadidae and Merluccidae), Scombridae (Thunnus sp.), Carcharhiniformes, Ommastrephidae and Loliginidae, all products for which substitution phenomena are very common (Pardo and Jiménez 2020; Marchetti et al. 2020; Silva et al. 2021). To favour the selection and application based on informative CD, it is necessary to associate the species name with the geographical origin, or with adjectives that evoke morphological characteristics known to the final consumer (Tinacci et al. 2019). Thus as a reference and as required by Regulation EU No. 1379/2013, trade names from the FAO catalogues could be used as a guide for the allocation of new CD after translation in Bulgarian language. Also, it would be useful to maintain local or regional names by making them official, in accordance with the provisions of European legislation (Regulation EU No. 1379/2013, Article 37).

4 Conclusion

This analysis shows that there is a clear will of the national Bulgarian legislator to cope with the EU requirements. The updated list specifically enhances local productions. Nevertheless, this newly enacted list only partially meets the requirements of the European legislator in terms of correct identification and labelling of seafood products on the national market.

Major issues related to the SN validity and the non-adherence to market demands also highlight the ineffectiveness of the current list for retail seafood products and the need to provide a substantially revised version. A rapid attempt might be done to merge the new and the old list as seen in other list updates of Member States, and by including additional species.

Notes

https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/collection/asfis/en. Accessed 25 July 2022.

https://www.fishbase.de/home.htm; https://www.sealifebase.se/search.php. Accessed 25 July 2022.

https://www.marinespecies.org/. Accessed 25 July 2022.

References

Cawthorn DM, Baillie C, Mariani S (2018) Generic names and mislabeling conceal high species diversity in global fisheries markets. Conserv Lett 11(5):12573. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12573

Cawthorn DM, Murphy TE, Naaum AM, Hanner RH (2021) Vague labelling laws and outdated fish naming lists undermine seafood market transparency in Canada. Mar Policy 125:104335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104335

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) (2011) No 404/2011 of 8 April 2011 laying down detailed rules for the implementation of Council Regulation (EC) No 1224/2009 establishing a Community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules of the Common Fisheries Policy OJ L 112:1–1534

Council Regulation (EC) (1996) No 2406/96 of 26 November 1996 laying down common marketing standards for certain fishery products OJ L 334:1–1512

Council Regulation (EC) (2009) No 1224/2009 of 20 November 2009 establishing a community control system for ensuring compliance with the rules of the common fisheries policy. OJ L 343(12):1–50

Council Regulation (EU) No (2013) 1379/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2013 on the common organisation of the markets in fishery and aquaculture products. OJ L 354(12):1–21

EUMOFA (2019) Country analyses 2014–2018 edition. https://www.eumofa.eu/documents/20178/136822/Country+analyses.pdf

FAO (2022a) ASFIS list of species for fishery statistics purposes. Fisheries and Aquaculture Division. Rome. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/collection/asfis/en

FAO (2022b) Fishery and aquaculture country profiles. Bulgaria. Country profile fact sheets. Fisheries and Aquaculture Division. Rome. https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/facp/27/en

FAO (2022c) Aquaculture market in the Black Sea: country profiles. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8551en

Gogaladze A, Son MO, Lattuada M, Anistratenko VV, Syomin VL, Pavel AB, Wesselingh FP et al (2021) Decline of unique Pontocaspian biodiversity in the Black Sea Basin: a review. Ecol Evol 11(19):12923–12947. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.8022

Klisarova D, Gerdzhikov D, Kostadinova G, Petkov G, Cao X, Song C, Zhou Y (2020) Bulgarian marine aquaculture: Development and prospects—a review. Bulg J Agric Sci 26(1):163–174

Lowell B, Mustain P, Ortenzi K, Warner K (2015) One name, one fish: Why seafood names matter. https://usa.oceana.org/OneNameOneFish

Marchetti P, Mottola A, Piredda R, Ciccarese G, Di Pinto A (2020) Determining the authenticity of shark meat products by DNA sequencing. Foods 9(9):1194. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9091194

Ordinance No 4 of 13 (2006) January 2006 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry on the terms and conditions for the first sale of fish and other aquatic organisms. Official. SG. 14/14.02

Ordinance № 13 of 30 November 2021 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry on the terms and conditions for the first sale of fishery products. Official. SG.103/10.12.2021

Paolacci S, Mendes R, Klapper R, Velasco A, Ramilo-Fernandez G, Muñoz-Colmenero M, Potts T, Martins S, Avignon S, Maguire J, De Paz E, Johnson M, Denis F, Pardo MA, McElligott D, Sotelo CG (2021) Labels on seafood products in different European countries and their compliance to EU legislation. Mar Policy 134:104810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104810

Pardo M, Jiménez E (2020) DNA barcoding revealing seafood mislabeling in food services from Spain. J Food Compos Anal 91:103521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2020.103521

Raykov V (2020) Characteristics of the Bulgarian Small-Scale Fisheries. In: Pascual-Fernández J, Pita C, Bavinck M (eds) Small-scale fisheries in Europe: status, resilience and governance. MARE pub series, vol 23. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37371-9_4

Raykov VS, Triantaphyllidis GV (2015) Review of driftnet fisheries in Bulgarian marine and inland waters. J Aquat Mar Biol 2(2):00017

Shivarov A (2021) Global interdependencies in seafood trade: the case of Bulgaria. Izvestia J Union Sci Varna Econ Sci Ser 10(3):110–121

Silva AJ, Hellberg RS, Hanner RH (2021) Chap. 7: seafood fraud. In: Hellberg RS, Everstine K, Sklare SA (eds) Food Fraud Academic Press, pp 109–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817242-1.00008-7

Tinacci L, Stratev D, Vashin I, Chiavaccini I, Susini F, Guidi A, Armani A (2018) Seafood labelling compliance with European legislation and species identification by DNA barcoding: a first survey on the Bulgarian market. Food Control 90:180–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.007

Tinacci L, Giusti A, Guardone L, Luisi E, Armani A (2019) The new Italian official list of seafood trade names (annex I of ministerial decree n. 19105 of September the 22nd, 2017): strengths and weaknesses in the framework of the current complex seafood scenario. Food Control 96:68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.09.002

Tinacci L, Stratev D, Zhelyazkov G, Kyuchukova R, Strateva M, Nucera D, Armani A (2020) Nationwide survey of the Bulgarian market highlights the need to update the official seafood list based on trade inputs. Food Control 112:107131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107131

Todorov A (2020) GAIN report number BU2020-0021. Fish and seafood market brief—Bulgaria.https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/report/downloadreportbyfilename?filename=Fish%20and%20Seafood%20Market%20Brief%20-%20Bulgaria_Sofia_Bulgaria_4-11-2017.pdf. Accessed 15 Oct 2019

Xiong X, D’Amico P, Guardone L, Castigliego L, Guidi A, Gianfaldoni D, Armani A (2016) The uncertainty of seafood labeling in China: a case study on cod, salmon and tuna. Mar Policy 68:123–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2016.02.024

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted within the National Scientific Program “Healthy Foods for a Strong Bio-Economy and Quality of Life” approved by DCM № 577/17.08.2018 and funded by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università di Pisa within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This study was conducted within the National Scientific Program “Healthy Foods for a Strong Bio-Economy and Quality of Life” approved by DCM № 577/17.08.2018 and funded by the Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Lara Tinacci, Andrea Armani and Deyan Stratev. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lara Tinacci and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tinacci, L., Stratev, D., Strateva, M. et al. New official Bulgarian list of seafood trade names: coping with EU labelling requirements and market trends to enhance consumers’ informed choice. J Consum Prot Food Saf 17, 395–406 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-022-01397-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00003-022-01397-7