Abstract

Reindeer herding is a complex, highly mobile, and environmentally adaptive form of livestock management, and a traditional way of life, practiced by indigenous peoples across the circumpolar Arctic. Given its distinctive characteristics, appropriate economic governance and regulation of the practice demands a clear understanding of its social, cultural, and environmental characteristics. In the following, we outline some of these and discuss their implications for economic management of the practice, with reference to the case of Norway in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. In closing, we identify some key current threats and challenges that confront reindeer herding and present some suggestions for enhancing its economic viability and resilience, based on a strategy of revitalizing core economic and social mechanisms.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

Reindeer herding has been practiced in the indigenous Sámi areas of Scandinavia and Russia for centuries. Over time, the gradual solidification of national borders in the region – the border treaty between Norway and Sweden in 1751 and the border closure with Finland in 1852 – has divided the Sámi territories, creating distinct legislative and administrative regimes and thus leading reindeer pastoralism to move toward nationally distinctive forms in each country. In Norway, implementation of the first Reindeer Herding Agreement (1976) and the new Reindeer Herding Act (1978) continued an integration of reindeer pastoralism into the national agricultural framework, a management regime based on principles of centralization, economic planning, industrialization, and scientific rationalization. Within this framework, the reform and restructuring of indigenous pastoralism unfolded along lines that were sometimes ethnocentric – by importing organizational or administrative concepts from other agricultural sectors, for example, or by “optimizing” herd structures in line with narrowly defined parameters for productivity that disregarded traditional indigenous knowledge of herd composition (Bjørklund, 2004).

Within a framework dominated by naturalized assumptions based on practices from sedentary agriculture, reindeer pastoralism has tended to appear as a sub-par, highly inefficient form of livestock ranching, governed with limited attention to the complex social, economic, and environmental characteristics that distinguish it. Given the challenges of climate change, land encroachment, and predator population management, a continuing lack of clear understanding of reindeer pastoralism from national authorities has been pinpointed as a main threat to Sámi reindeer herding in Norway (Benjaminsen et al., 2016). Impacts on reindeer herding from multiple drivers of environmental and social changes are exacerbated by indigenous peoples’ lack of voice in governance strategies, management, and adaptation responses (Eira et al., 2018). The management models for Sámi reindeer herding that were implemented in Norway in the 1970s did not include reindeer herders’ traditional knowledge as a basis for decisions and management (Eira et al., 2018), and still today, traditional knowledge is deprioritized in public management in favor of scientific knowledge and notions of rationality and practicality (Turi, 2016). Presently, as a result of a series of complex trends – including social, technological, and environmental change, shifting demographics, and increased reliance on mechanized transport and fossil fuels – Sámi reindeer herding in Norway finds itself at a precarious juncture, where administrative interventions have rewritten practice, amplifying and sometimes even creating the very problems they were designed to prevent.

As a consequence of the factors mentioned above – and due to comments from referees – the authors would at this point like to flag that their chapter is critical to the policies that have been pursued by the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture since the mid-1970s. Dr. Reinert, who was invited to take part in annual negotiations between the Reindeer Herders’ Association (NRL) and the Norwegian government in the early 2000s, was deeply disturbed by several issues during the meetings.

-

1.

The extremely uneven balance of power in the negotiations. On one side of the table, the government was represented by seven ministries, and the Sámi Parliament and, on the other side of the table, NRL, which at the time had one full-time and one half-time employee and Dr. Reinert as a consultant, but otherwise very few resources at hand.

-

2.

The lack of understanding of nomadism – which is an academic subfield in anthropology – on part of the government “experts,” contributing to an eerie feeling of “internal colonialism” taking place.

-

3.

The strong position of the national farmers’ meat cooperative and monopoly (Norsk Kjøtt) in the government’s delegation. Reindeer meat was the only competitor to Norsk Kjøtt, and the vested interest (Veblen, 1919) of the (ethnically Norwegian) farmers in Norsk Kjøtt toward the Sámi herders was seen by Dr. Reinert as economic discrimination and evident structural racism. Statistics from the annual reports published by the Ministry of Agriculture itself in Fig. 5.1 shows the successful policy to drive down the price of reindeer meat as compared to the most expensive ethnic Norwegian meat (filet of beef). Figure 5.2, also with the data from the Ministry of Agriculture itself, shows how reindeer herding went from being an unusually profitable activity to being a loss-making one.

-

4.

Rogue behavior. Mr. Aslak Eira, Chair of the NRL, expressed that “it is good that you are here, Erik, then they behave in a more civilized way. Last year they told us to leave the meeting room and gave us the choice between either by the window or by the door” (the meeting room was on the ground floor on the main governmental building in Oslo).

-

5.

Ministry of Agriculture governing of these matters, through the Reindeer Herding Organisation (Reindriftsforvaltningen) in Alta, has alone in effect held all the powers which in democratic societies are consciously separated: legislative, executive, and judicial (Montesquieu, 1748/1977). Reindriftsforvaltningen makes the rules; they police the rules and also serve as the court of appeal. This profoundly undemocratic treatment of the national ethnic minority was reported to the Parliamentary Ombudsman in the early 2000s. After these sequences of events, Prof. Reinert vividly remembers the shame he felt by being a Norwegian.Footnote 1

This led to an urge on his part to understand the context and situation of reindeer herders, which we shall now explore.

5.2 The Geographical and Climatic Context

Arctic reindeer pastoralism distinguishes itself from more “conventional” livestock industries in a number of key respects. Understanding how nomadic herding differs from conventional livestock production is a precondition for understanding the present problems of Norwegian reindeer herding, problems that are partly different from those of the herders in neighboring Sweden and Finland.

However, in order to understand the organization structure of the reindeer herders, it is necessary to understand the special geography and climatic context in which the Sámi operate. To illuminate this discussion, we shall now go into examples from other geographical areas and alternative theoretical frameworks (see also Reinert et al., 2009, 2010). When the European explorers gradually came to understand the Americas, they found it somewhat contradictory that what to them looked like huge fertile prairies in North America had a relatively small population, while the seemingly inhospitable Andes probably had the largest population density on the whole continent.

A good explanation for the high population density is found in the landscape ecology of extreme climates as explained by German geographer Carl Troll (1899–1975). Troll envisioned a world consisting of a huge number of ecological niches, and with differences in altitudes, these would form what he called landscape belts (Landschaftsgürtel). On the prairies, one could travel weeks inside the same climatic niche, while in mountainous areas like the Andes, very different ecological niches – like those fit for growing cotton and those fit for growing potatoes – are found relatively near to each other (Troll, 1966).

Carl Troll’s work was continued by anthropologist John Murra (1916–2006).Footnote 2 Studying a huge number of Peruvian court documents from colonial times and present annual migration patterns, Murra found that Peruvian labor had been highly mobile between the different ecological niches, sequentially following the seasons where harvests and other work were found. Murra developed the concept of a “vertical archipelago” of ecological niches that – due to the great variations in climate from sea level to more than 4.000 m above sea level – are relatively close to each other in terms of kilometers and travelling time (Murra, 1975). If we look at the cradle of European agricultural civilization – in places like Armenia and Georgia – we can observe the same short geographical distances between climate zones, e.g., between a climate suitable for cotton and a climate suitable for potatoes (seen in today’s crops).

What the Arctic and sub-Arctic areas have in common with the Andes is often short distances between geographical niches. Travelling in Finnmark, one can observe sharp differences in temperatures. In summer, reindeer find the last patches of snow (jassa) where they are relatively free from insects. In our view, reindeer herding and the annual migrations must be understood in Murra’s framework as a sequential usufruct of different ecological niches which – like in the Andes – are often close to each other (see Fig. 5.3).

The geographical proximity of widely different ecological niches (or landscape belts) in the Andes: the proximity of qualitatively different niches – from sea level to 4.000 m above sea level – allowed for a very high population density in the pre-Columbian cultures here. Different products would dominate niches at different altitudes: fish and cotton near the sea level, fruits higher up, then maize and further up potatoes, and at the top level around 4.000 m quinua, a key crop related to millet (millet was an important crop in Europe before the arrival of potatoes and maize from the Americas), and the herding of different types of animals, llamas, alpacas, and vicuñas. In the Arctic, such ecological niches can be even closer together. The efficient management of herding across this “archipelago” of different ecological niches is at the very core of reindeer herding. (illustration Troll: 1931/1932, reproduced in Troll, 1966, p. 111)

Moving between different ecological niches is the key to traditional nomadism, also in the Andes and for the reindeer herders in Northern Eurasia. Moving according to where nature produces food (for animals and/or for people) is the very key to survival.Footnote 3 The more extreme the climate, the number of ecological niches needed to survive will increase. In other words, the more extreme the climate, the longer the annual migrations will tend to be. So, in Southern Norway, one would expect shorter migration routes than in Finnmark. Even before the recent changes in climate, the weather varied from year to year. The Sámi saying that “one year is not the other year’s brother” means that pasture use will have to vary. Here administrative borders become a hindrance: during the problematic years when the ground froze over early, herders could in the old days move into the forests in Finland where the ground would not be frozen over with ice, as one example.

Later we shall show how “normal” climatic cycles have affected reindeer herding. Now, with a more unpredictable climate, herders would ideally need access to a larger number of ecological niches. However, the opposite is happening.

Temperature is of course important, but in Carl Troll’s “geography of extreme climates,” one particular range of temperature, the days of the year when the temperature is both above and below zero during the same 24 hours, is crucial. Whether it is 20 or 30 below zero is normally not important; what German geographers refer to as Frostwechselhäufigkeit – how often you find freezing and thawing in the same 24 hours – is extremely important.

In the Andes, a high Frostwechselhäufigkeit would allow the production of freeze-dried potatoes (chuño), freezing the potatoes every night and subsequently drying them in the sun during daytime. It has been argued that the nutritional importance of chuño explains why the three main pre-Columbian cities in present Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia all are located above 3.000 m: Quito, Cuzco, and the area around Lake Titicaca. At this altitude, the frequency of Frostwechselhäufigkeit is sufficient to make the production of chuño possible.

For reindeer herding – on the other hand – the phenomenon of Frostwechselhäufigkeit is normally a negative feature. It may lead to “locked pastures”: ice layers could form in the snow, making it difficult – especially for the females and calves – to have access to the pastures under the ice. Sámi language holds several hundred terms for snow and snow conditions (Eira, 2012). For instance, the northern Sámi term goavvi refers to extremely bad grazing conditions (beyond simply bad winters) that cause starvation and loss of reindeer and subsequent negative impacts on herders’ economy and organization (Eira et al., 2018). Interviews with elderly herders some 20 years ago indicated that the sharp drop in the number of reindeer that could be observed in 1931 (see Fig. 5.4) was due to early locked pastures and to a year when most calves died. Understanding snow and snowchange are of paramount importance for reindeer herding under climate change with increasing extreme weather events, where a particular concern is that the frequency of goavvi seems to display an increase in some reindeer herding areas (Eira et al., 2018).

Under this heading of geographical and climatic context, we refer back to the problems listed initially, which in the view of the authors have led to a systematic mismanagement of reindeer herding in Norway. Completely ignoring that nomadism is actually an academic subdiscipline in the science of anthropology, the employees dealing with reindeer herding in the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture (hereafter LMD) were largely graduates from the Norwegian School of Agricultural Sciences (now NMBU). Employing the logic of normal animal husbandry – with an almost complete lack of attention to the Arctic climatic context – several crucial factors were ignored. The fact that the one person who actually had a Ph.D. in reindeer husbandry had done his thesis based on data from the southernmost herders – around Lake Femunden – could lead to refusal to recognize the cyclical nature of the reindeer population.Footnote 4 Any student of ecology would know that the animal population – from lemmings to ptarmigan (a fowl) – is cyclical in Northern Norway. This was arguably in effect not recognized by the Ministry of Agriculture.

5.3 The Social Organization

Reindeer herding is essentially a pre-capitalist mode of production, a mode of production that has survived only in the most inhospitable climates of the planet, in the Arctic, in the extreme mountainous areas of the world, and in the deserts of Africa. Day-to-day interaction with a variable and capricious nature makes this mode of production the most sustainable anywhere: if all the amenities of modern life – from heat and electricity to modern communications – broke down, reindeer herders would likely be among the least affected in Norway. They could retire to the self-sufficiency of their old ways.

Karl Polanyi (1944) is the one who most efficiently has contrasted capitalism to pre-capitalist societies. The organizational units are extended family groups, in the Andes called ayllu and in Sámi called siida. Work inside a siida is divided and shared as a kind of joint venture inside a family group. In Norwegian, the traditional word dugnad renders something of the same idea. It is important to note that the ownership of reindeer is individual, but the management of the herd is done by the siida “joint venture.” If the tasks so require, the siida can also be split according to seasons and conditions (Sara, 2001).

Karl Polanyi (1944) has pointed to what he calls the three fictitious commodities of capitalism that are all missing in pre-capitalist societies: money, labor as a commodity, and private ownership of land. This still today essentially applies inside the Sámi production system, while their relationship with the outside world of course is organized according to the market system. Instead of land ownership, pre-capitalist societies – including the Sámi herders – have traditional and well-organized sequential usufruct of land. The different groups have the right to use the land at different times of the year.

Such climatic differences and variations are vital to understanding its conditions for productivity, and they also shape the scope of its interactions with the market. An appreciation of the manner in which reindeer herding is embedded in and interacts with its environment is an important first step. In the perspective of pre-capitalist cultures, reindeer herding is “normally” organized.

The elements for understanding an appropriate governance of reindeer herding encompass a wide range of factors: the mobility and autonomy of animals; the complex and variable risks presented by constantly shifting environments; the skill required to herd effectively within them; the structure of the herding year, which follows the reproductive cycle of the animals and concentrates reindeer meat production into seasonal peaks of availability; and so on (Reinert et al., 2009; 2010). Under this unpredictable reality, the concept of fuzzy logic can illustrate reindeer herders’ decision making (Eira, 2012). The kind of knowledge needed to understand and manage reindeer herding is a type of knowledge which is not found in written form: much of it is what is scientifically called traditional knowledge or tacit knowledge which is accessible to the practitioners, as pointed out by Michael Polanyi (1966).

Reindeer are migratory animals, over which herders exercise a clear but yet limited degree of control. While one can see intensive livestock production as founded on an unlimited human control of the animals across time and space, with an underlying premise that man can control nature, reindeer pastoralism is at the other end of this scale: reindeer herding peoples have always known that they must work in collaboration with nature, not against it (Turi, in Oskal et al., 2009). Throughout the year, reindeer act with considerable autonomy with regard to (for example) finding suitable grazing, seeking shelter, defending themselves from predators, or moving to high ground to protect themselves from insects. Skilled human practice complements and guides the “semi-domesticated” animals, particularly at critical junctures, but does not supplant their agency – in other words, pastoralism differs fundamentally from agricultural practices based on close control and confinement of “captive” animal populations (Magga et al., 2001). The need for mobility and autonomy follows in large part from the complex and rapidly changing demands of Arctic environments and landscapes: an environmental variability that is encoded in traditional herder knowledge through maxims, proverbs, and anecdotes, but also through a complex technical language developed to describe, in great detail, the characteristics of environmental features such as snow (see Eira et al., 2018). Within such environments, a key skill of herding lies in identifying and making use of specific ecological niches that meet the shifting requirements of the herd (Reinert et al., 2009). This in turn demands an ongoing and finely tuned observation of pastures, temperature conditions, ice and snow qualities, weather systems, and wind directions – all factors which determine access to pastures and the behavior of the herd (Heikkilä, 2006). Such monitoring is particularly important on the winter pastures, where the availability of feed through snow becomes vital and where, under certain circumstances, the ability to rapidly and precisely move a herd to the appropriate grazing grounds can determine life or death for a large number of animals. Qualities of the snow cover – such as density, hardness, and depth – are key to determining access to forage and therefore the suitability of winter grazing grounds (Tyler et al., 2007; Eira, 2012). These qualities in turn can vary rapidly and over short distances, depending on local landscape features, weather systems, and other factors (Sara, 2001).

Given mobile animals, rapidly changing conditions, and a high-risk environment, flexibility is a key dimension of pastoral practice, and sustaining such flexibility is a vital requirement for its continued development and future flourishing (Reinert et al., 2010). Such flexibility can take a range of forms – from the ability of individual herders to locate and utilize microclimatic niches, to their ability to control the composition of their herds and regulate the rate at which living animals are transformed into meat, to the flexible movement of labor in and out of the practice, including the ability to supplement incomes with alternative forms of employment during unfavorable periods and “bad years.”

5.4 Nature and Social Organization vs. the Government

We initially referred to the problems of negotiating with the government. We elaborate on some of them in the bullet points below. One overriding problem, evident to an outsider, was that there were important cultural problems hindering effective communication between the ministerial bureaucrats and the Sámi herders. In Norway, like generally in Western Europe, it is assumed that silence in a negotiation is a sign of approval. Sámi culture, on the other hand, is more in line with the Japanese in this matter: it is impolite to openly disagree. A second basic problem is that the main Ministry (Agriculture) day-to-day management deals with the agricultural cooperatives, in the case of meat a national semi-monopoly (Norsk Kjøtt; see below), which is the main competitor for reindeer meat. That reindeer meat was more expensive than the best beef cuts appeared to be a problem for the farmers in Norsk Kjøtt, resulting in the mechanism described in bullet point one below:

-

The insistence on a stable production and stable prices (in effect set by the LMD as in a planned economy) led to some years of “overproduction” and some years of “underproduction” compared to fairly stable demand. Prices were allowed to fall in years of high production, but only extremely slowly allowed to rise as production plummeted, reflecting the vested interest of Norsk Kjøtt (see Fig. 5.4 for the dynamics).

-

Traditionally reindeer steak – from adult animals – was a luxury item among urban consumers. However, with the logic of minimizing the number of animals grazing in winter and maximising meat production, LMD started subsidizing the slaughtering of young calves, which impacted the product ranges and the quality of the meat in the eyes of the consumers.

-

An extreme focus on females and calves led to a policy that would have been logical inside a barn: males were there only for reproduction processes. However, Frostwechselhäufigkeit would “lock” access to the pastures for calves and females. Males – and especially the castrates – had the very important task of literally breaking the ice between the animals and the food below. However, the Norwegian government, by forcing the percentage of females up to 90%, made the flocks extremely vulnerable not only to “locked pastures” but also to predatory animals. The castrates kept their horns and were the “gentlemen of the tundra” who not only broke the ice and gave females and calves access to the rich food below but could also protect the herd from predatory animals.

-

Although the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture would never likely not admit to it, the almost systemic cultural miscommunication between the Ministry (LMD) – and consequently Norwegian society at large – and the Sámi herders in practice clearly boils down to a form of structural racism. The term of “locked pastures” was in Norwegian society at large normally translated as “overgrazing” (overbeite). Referring to Fig. 5.4, whether the number of reindeer was at their cyclical peak or their cyclical trough, the government mantra was always “too many reindeer on the tundra.” Underlying the whole problem was a seemingly colonial type of economic relationship between the Sámi culture and the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture (Reinert, 2007). In a historical international context, colonial ministries tended to have some knowledge of anthropology, and in the United States, in the similar Bureau of Indian Affairs, a Native American has traditionally been (at least) second in command. In Norway, the Ministry of Agriculture (LMD) has been given the de facto economic powers of a Colonial Office (cf. Reinert, Op.cit).Footnote 5 Traditionally, the unit in charge of reindeer herding has not spoken the native languages.

The Norwegian governance system for reindeer pastoralism presents a case of very strong bureaucratic centralization – seemingly more so than in other Scandinavian countries. In 2000, to supervise less than 600 individual herding units, the Norwegian Reindeer Herding Administration employed more than 50 people (Lie & Nygaard, 2000). This extensive administrative structure produces a constant flow of detailed and rapidly changing regulations. On one level, this extensive structure could provide a social and economic safety net for herders: a structure capable of providing support or subsidies in “bad years” and mitigating the negative economic impact of climatic change and extreme events. Currently, however, questions are raised as to the capacity of this system to do this: a joint letter from 34 of the 39 mayors of Troms and Finnmark County in Norway of March 23, 2020, to the Norwegian Minister of Agriculture pleads for emergency help, demanding that the Minister take responsibility to secure economic resources for reindeer herders given the current crisis observed with critical snow conditions (NRK Sápmi, 2020). On another level, incentive structures and subsidy systems can create patterns of dependence (Paine, 1977) and negative feedback cycles, both of which leave herders increasingly at the mercy of unpredictable shifts in policy, opinion, and regulatory parameters – a particular concern in countries such as Norway, where reindeer pastoralism and Sámi interests have in large part been historically shaped by terms dictated by the shifting interests of central powers.

Embedded as it is in risky and unpredictable environments, the productivity of Arctic reindeer pastoralism is not easily reducible to straightforward projections or to simple economic formulas for optimization. In terms of meat production, for example, a particular herd structure may optimize annual yield by favoring fertile cows and minimizing the proportion of mature bulls, but the same structure may also weaken the ability of the herd to defend itself against predators or extreme snow conditions, thereby exposing herders to higher losses during difficult periods; similar issues arise with regard to other aspects of herding practice. Unlike livestock managers operating with artificial or controlled environments, pastoralists must account with a range of variables that lie beyond their direct control, predators, weather, climate, and snow patterns, all of which may affect the annual productivity and meat output of their practice, in ways that are difficult to predict. Putting it simply, a key corollary of this embedding of pastoralism in variable environments is variable productivity – that is to say, an inherent irregularity in meat production and supply.

Within a given year, this variability is given primarily by the animals’ annual cycle of migrations and calving, which dictates that slaughter takes place only at certain times of the year, generally during autumn and winter roundups: during the rest of the year, the animals may be busy mating, bulking up for the winter, or calving, and rounding them up would be unduly disruptive. This makes the availability of fresh reindeer meat seasonal, a function of cycles that are not (and cannot be) artificially manipulated. Therefore, another key trait of reindeer pastoralist production is seasonality. Between years, furthermore, the meat output of the industry cannot easily be projected as an annual constant. Herd sizes and animal health vary from year to year, according to environmental and human variables; decisions concerning which and how many animals to slaughter are also made (and changed) on the basis of the long-term objectives, the cash requirements of individual herders or the district, the overall condition of the herd, the estimates concerning coming years, the fluctuations of the market, the important life events, and so on. Environmental constraints and non-market considerations thus make the supply curve for reindeer meat irregular – with production peaking at certain times of the year and an oscillating annual output dependent on conditions that may range from the overall state of grazing access through snow to the degree of financial insecurity perceived within the industry.

Running directly against this, a key goal of successive Norwegian administrations has been precisely to regulate the meat production in reindeer herding: to ensure social, economic, and ecological stability by stabilizing the meat outputs of the reindeer industry at a predictable level (Reinert, 2006). This pressing demand for a relatively stable meat output – both within 1 year and between years – limits the choices of herders and constrains their options to slaughter fewer animals in a given year. We suggest that this aim is based on a theoretical misrepresentation of the variability and cyclicality of reindeer pastoralism as a practice embedded in a complex, rapidly shifting, and high-risk environment – ill-informed at best, dangerous at worst.

As we indicated, a key point of reindeer pastoral productivity is that it functions in close coupling with a set of highly variable environmental conditions – and that its production is therefore also necessarily variable. Given a more or less regular level of demand, sustained from year to year, such variability generates two kinds of crisis: a crisis of overproduction at peak productivity and a crisis of underproduction at the point of minimum productivity. In the former type of crisis, reindeer numbers are large, mortality is low, and high annual production exceeds the capacity of the market to absorb products; during the latter, mortality may be high, the animals weak, and losses to predatory animals at a peak: whatever the reason, slaughtering is limited, and the amount of meat that reaches the market is significantly below rates for a “normal” year. At minimum production, the volume available for sale is very low; at the peaks, conversely, production exceeds normal demand. In a normal market situation, low production volume or underproduction would increase the unit price and thereby compensate producers. In cases of overproduction, similarly, prices per unit of production would fall as production exceeded demand. In resource-based industries such as agriculture, fishing,Footnote 6 or mining, market forces may thus cause total production value to peak when production volume is at its lowest. In the Norwegian administration of reindeer herding, however, such mechanisms were effectively neutralized – often, by the very policies designed to support the industry (Reinert, 2006; Reinert et al., 2009).

Today there exists no theoretical-empirical economic model adapted or genuinely suitable for reindeer herding as a traditional, family-based, indigenous, nomadic livelihood in cyclical and highly variable natural environments (Pogodaev & Oskal, 2015). Still against this backdrop, reindeer herding management authorities insist on detailed regulations and control of operational reindeer herding practices, e.g., herd structure, a focus on slaughtering of calves, reindeer herding district usage rules, reindeer counting, and so on.

There could be a vicious circle at work here. The government’s lack of understanding of the basic nature of reindeer herding – and any resulting frustration as measures do not work as envisioned – leads to an urge to manage in detail. The basic inability of the government system to recognize the natural cyclicality of reindeer herds is at the core of the problem. Rejecting traditional knowledge as “superstition,” for the Ministry in Oslo with their background in normal agriculture, the herds of the tundra to them appear to be a disorganized barn. Regardless of the position in the cycle – see Fig. 5.4 – to LMD there are always “too many reindeer on the tundra.” Historically versed in dealing with an unpredictable nature, the herders now also had to deal with an unpredictable government. On the one hand, to attempt to govern something you don’t understand is a serious matter. Medieval philosophers thought about the importance of docta ignorantia, being aware of what you do not know. There, however, seems to be few signs of this in the Norwegian government organization on this issue. Rather the situation at times reminds one of what US author Upton Sinclair described in 1934: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

It was the national states that started public management of reindeer herding, which up until that point had essentially been a fully self-managed system, a system which had been present in Scandinavia since before national borders were drawn in the North (Fig. 5.5). In Norway, this management was introduced through different legal and economic instruments from especially the latter part of the 1800s (the assimilation period), the latest of which include the Reindeer Act of 1933, the Reindeer Herding Agreement System of 1976, the Reindeer Act of 1978, and the Reindeer Act of 2007.

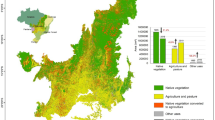

Map showing the Sámi ethnic language groups in Northern Fennoscandia and on the Russian Kola Peninsula. The linguistic groups largely correspond to the migration areas, from the summer pastures on the coast to the winter pastures in the inland. Just like in Africa, the borders of the Nordic nation-states in the Nordic countries (dotted lines mark) came to divide the ethnic groups. This created challenges to the herders, but to which subsequent adaptation took place

We now suggest, it is rather about time to understand reindeer herding for what it really is, namely, a family-based, indigenous, nomadic, pastoral way of life, and a system especially adapted to utilizing marginal resources under cyclicality and constant variability.

5.5 The Negative Effects of Government Intervention

In 2000 and 2001, one of the authors undertook a study of profitability in the Norwegian reindeer industry, on behalf of the Ministry of Agriculture, which illustrates important points in the development of economic governance of reindeer herding. An early finding in this study was that the reindeer meat market appeared to be organized around a remarkable two-tier price system (Reinert, 2006; also Reinert, 2002). Most herders were selling their animals to so-called listed slaughterhouses, ensuring their own eligibility for subsidies in return for a price of about 42 kroner per kilo on the hoof. Other herders, on the other hand, were able to operate outside the subsidy system and sell on the open market, obtaining a price of more than 60 kroner per kilo for their own slaughtered meat – 50% more than herders operating within the subsidy system. To an external observer, particularly one trained in economics, this was a peculiar, even astonishing situation – particularly so, given the perception of reindeer herding in Norway as a highly subsidized indigenous industry, supposedly sustained through a large support apparatus (Fig. 5.1).

In 2000, the first-hand market value of reindeer meat produced in Norway was about 70 million Norwegian kroner (Reinert, 2006). At the time, there were approximately 550 individual production units within the Sámi reindeer herding areas, all under the supervision and management of the Reindeer Herding Administration, or Reindriftsforvaltningen – which employed around 50 people, with an annual budget of over 40 million Norwegian kroner and reporting to the Ministry of Agriculture (Lie & Nygaard, 2000). In addition, the annually negotiated agreement between reindeer herding and the state had at the time a base budget of 80 million, with an additional 25 million kroner earmarked for reindeer herding over the budget of the Ministry of Environment. Direct annual government expenditures on reindeer herding thus added up to 140 million kroner – or approximately twice the value of the first-hand production in the reindeer herding industry. As late as 1976, with a minimum of government intervention or subsidies, reindeer herding had been a very profitable activity (see Fig. 5.2). Despite very high levels of government subsidy and a large public support, a quarter century later, this once-profitable indigenous industry was now operating with huge losses. Several questions lingered: How had this come to pass? If reindeer herding was so highly subsidized, where were these subsidies going? Who were they benefitting? What were the underlying causes?

We trace the problem back to the late 1970s, when reindeer herding and reindeer meat production in Norway first came under direct government control, through the regulatory framework of the Reindeer Herding Act (1978) and the first annual Reindeer Herding Agreement (1976), negotiated between herders and the Norwegian state. In Norway, relations between the government and the national agricultural sector are regulated through an annually negotiated agreement that defines the economic framework and subsidies for the sector – including also the so-called target prices [målpriser] for agricultural products. In 1976, drawing on this model, the first Reindeer Herding Agreement was set up between the government and the Norwegian Sámi Reindeer Herders’ Association (Norske Reindriftssamers Landsforbund or NRL). Establishing policy objectives, an economic framework, and subsidy parameters, including “target prices” for reindeer meat, this agreement repositioned reindeer pastoralism within the context of Norwegian post-war agricultural policy – a policy context that had been shaped, in no small part, by the twentieth-century project to equalize the market power of agriculture compared to industry and manufacturing, in the wake of the disastrous financial crisis of the 1930s (Reinert, 2006). Norwegian agriculture was historically composed of small units of primary production, but the twentieth century saw a concerted push toward achieving economies of scale in processing and distribution – both of which were managed as mass production systems, characterized by centralization and product standardization. Over the decades following the first Reindeer Herding Agreement, this orientation toward centralized mass production was applied to reindeer pastoralism, with problematic effects.

In the case of meat and meat products, the cooperative that managed and coordinated the production system was the Norwegian Office for Meat and Lard (Norges Kjøtt- og Fleskesentral) – established in 1931 – which subsequently became Norsk Kjøtt in 1990 and Nortura in 2006. Soon after the first Reindeer Herding Agreement was signed, faced with increasing volumes of reindeer meat, the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture delegated responsibility for marketing reindeer meat to this cooperative. Representatives from the cooperative were initially well received by the reindeer herders: they paid promptly and were easy to deal with. According to former employees of the cooperative, however, reindeer meat was at the time considered a competitor against the upper end of the beef market and, thus, a rival to the interests of the farmers who owned and ran the cooperative. Responsibility for reindeer meat had been forced on the cooperative by the Ministry of Agriculture: the herders, whose meat production comprised less than 2% of total domestic red meat volume, found that the government in essence had handed over their marketing to a competitor that dominated the remaining 98% of the market.

With no or little incentive for key actors to market reindeer meat, the stores of frozen meat started to mount, and with this came escalating storage costs. The Ministry of Agriculture intervened, using subsidies to effectively give the meat farmers’ cooperative a blank check to store – rather than sell – the frozen meat of their competitors. Subsidized in this fashion, the stores of accumulated meat continued to grow. Year after year, at the annual agreement negotiations, herders heard the same story: there was too much reindeer meat in stock; therefore, the negotiated “target price” for reindeer meat must be reduced. This “target price” slowly became the only price paid for reindeer meat, and over time, the sums paid to Norsk Kjøtt for the costs of freezing the growing mountain of unsold reindeer meat – paid from the annual sum of subsidies granted to the herders by Parliament over the terms of the agreement – reached enormous proportions, sometimes up to half the first-hand market value of annual meat production in the industry. Within the incentive structure produced by government policy, freezing and storing reindeer meat may well have been more profitable than marketing and selling the same meat. Another mechanism thus institutionalized was shaking off the competition for the key players, introducing the danger of price dumping as a key risk for any new actors wanting to enter the industry as a real barrier to entry, and also impacting existing actors.

As the reindeer herders started to lose money, the Norwegian government responded by establishing arguably what were effectively social welfare programs, granting subsidies based on the volume of meat produced while at the same time continuing to subsidize the storage of frozen meat. In order to keep reindeer numbers in check and prevent claimed overgrazing, such social payments were tied to slaughtering animals; to avoid fraud – i.e., herders counting the same slaughtered animal twice – an elaborate control system was set up that required the individually marked ears of slaughtered animals to be kept in frozen storage for months, subject to auditing by the Reindeer Herding Administration. A “double entry” bookkeeping system was thus established that kept track of all reindeer slaughtered in Norway. As a further layer of security against fraud, subsidies were only disbursed for reindeer slaughtered at state-approved slaughterhouses – i.e., the so-called listeførte slakterier or listed slaughterhouses. Herders who slaughtered at these slaughterhouses were paid only the low “target price” – forcing herders who depended on subsidies to sell their meat cheaply, while some herders, whose herds were sufficiently large to operate independently of government subsidies, could slaughter their reindeer independently and sell their meat locally at much higher prices. In this manner, the “listed slaughterhouses” could acquire reindeer meat cheaply and made money with little marketing effort – not least, through government payments for storing what reindeer meat they themselves did not sell. Government policy thus effectively created a monopsony – a monopoly on purchasing, supported by the government subsidy to herders, but controlled largely by non-Sámi actors. The government had uncoupled supply from demand, inserting itself as a “buffer” between the reindeer meat production chain and the market.

In 2002 – 26 years after the first Reindeer Herding Agreement – an estimated 80% of all reindeer in Sweden and Finland were slaughtered in establishments owned and controlled by herders. In Norway, the figure was approximately 20% (Reinert, 2002). In Norway, government interventions had let the farmers’ organization – Norsk Kjøtt – take over the part of the value chain where most of the value added was to be found: slaughtering, partitioning, branding, and marketing. The reindeer herders had been decoupled from the market and the end users, and in effect, control had been passed over to the farmers’ meat cooperative that managed the reindeer meat value chain to serve its own interests, often against the interests of the herders. When these restrictive measures were combined with the rapid escalation of new hygienic requirements for commercial slaughter from the 1970s onward, herders were effectively excluded from their own value chain, losing control over their own means of production, and were reduced to suppliers of raw material for slaughterhouse operators. The function of slaughter and meat elaboration in Norwegian reindeer herding, both as key elements of pastoral culture and as vital sources of profit, had been severely diminished. Possible ways out of this situation needs to be explored, which we will now turn to.

5.6 Challenges and Opportunities

During the last quarter of the twentieth century, the economic policies of the Norwegian government with regard to herding present a clear example of governance that was completely – and for some, catastrophically – at odds with the logic of herding, particularly with its ecological determinations. While most forms of agricultural meat production in Norway take place within stable, regulated environments – shielded from environmental variability or its effects – reindeer herding does not. Extrapolating the logic of stable and predictable outputs from other sectors, based on highly controlled production conditions, the Norwegian government implemented an inflexible “planned economy” that failed to take into account inherent variability in the practice they were regulating – separating the “target price” for reindeer meat from oscillations in productivity, but not to the advantage of the herding industry. An industry defined by its variable environment, and the resulting variable productivity, had been managed through a pricing regime premised on stability, which kept unit prices fixed independently of supply or demand. Rather than offsetting the negative aspects of a variable productivity, Norwegian economic policies thus amplified their effects, disconnecting the market mechanisms that could have mitigated the problems. Instead, the policies imposed by the government added to the economic vulnerabilities.

Compliance with the requirements of the state subsidy system forced herders to sell at prices far below the market rate – “subsidies” earmarked for indigenous herders were thus effectively channeled to non-indigenous operators in the meat industry. Over the span of a quarter century, government policy thus converged with broader trends – social, technological, economic – to shift reindeer pastoralism from a position of affluence and relative strength to one of relative poverty and dependence on state mechanisms of support.

As we suggested at the outset, the position of reindeer herding today is precarious – not least, because the inherent variability of the practice is still poorly acknowledged. Climatic variations are discussed primarily as random events causing occasional “crises” in an environment otherwise presumed stable. This problem is compounded by the fact that the two structurally distinct kinds of economic crises that reindeer herding is subject to – underproduction and overproduction – tend not to be clearly distinguished in Norwegian public discourse. One effect of this is to create the impression of an industry in a continuous state of crisis, an effect that is further accentuated by the tendency to define and operationalize “sustainability” as a fixed, stable number of reindeer, marking deviations from this number as a problem of responsibility – leading to a phenomenon we would term “cyclic irresponsibility,” as environmental fluctuations lead to regular “crises” and accusations against herders. Many of the changes that have taken place in the last few decades are irreversible, or very likely so. Some of them, however, are not. Here, in closing, we review some possible strategies for improving the economic situation of reindeer herding, centering on the notion of revitalizing core mechanisms and institutions of pastoral practice.

Reclaiming the Value Chain

Perhaps the most important effect of government intervention since the late 1970s has been to exclude most herders in Norway from the value chain of their own products, reducing them to providers of raw material within a commodity chain dominated by other actors. While there are exceptions, this remains the overall picture of the industry. Measures against this “colonial” situation – where the reindeer herders supply raw material on hoof – are a continued support of field and small-scale abattoirs, adaptive regulation designed to support local value generation, and systematic support for “alternative” products, e.g., traditional smoked meats. This will also increase financial returns on slaughter for individual herders, thereby incentivizing animal outtake and contributing to the stated government aim of increasing slaughter rates in the industry.

Localize Markets

Some of the negative social trends in recent years are linked to the disappearance of local reindeer meat sales and markets. This is a complex trend, which encompasses a range of factors – government-driven centralization, the industrialization of meat production, increasingly severe hygiene regulations, and enforced control of the market circulation of meat products – but the effects have been clear. With the loss of direct-to-consumer sales, reindeer herders also lost a key mechanism for establishing and maintaining personal social relations with local non-herders: with this loss have come increasing social distance, hostility, accusations, and escalating of conflict levels in herding areas. As a corollary of developing herder control over the later stages of the reindeer meat value chain, establishing a visible presence for reindeer herders as local providers of reindeer-based commodities will likely help consolidate relations, create social cohesion, and reduce social conflicts currently associated with pastoralism.

Revive Existing Mechanisms

On a related note, as a dimension of utilizing economic transactions to build local social integration, it may be useful to examine (with an eye to reviving) the relatively neglected institution of verdde –traditionally a form of close alliance or friendship between herders and non-herders which involved the exchange of favors and goods. An aspect of this institution involved non-herders, often coastal Sámi, owning a small number of reindeer in the herds of their herding verdde partners, a practice which was rendered problematic by the introduction of regulations that prohibited the ownership of reindeer by non-herders (Bjørklund & Eidheim, 1999) – again, an unintended consequence of measures ostensibly designed to support the industry. The institution nonetheless survives, on an informal level, but as a pathway to strengthening local relations between herders and non-herders, and reducing conflict, it may be relevant to explore options for reviving this and similar institutions (Reinert et al., 2010).

Decentralize Control

As the case of state (mis)management in Norway makes clear, centralized top-down control has not served the interests of reindeer pastoralism particularly well – herders are in some ways much like their reindeer, better left to manage for themselves. In Sweden and Finland – where the market forces have been allowed to rule more than in Norway – the herders themselves do most of the slaughtering. In an interview with the managing director of Polarica/Norrfrys – a main player in the Swedish market for reindeer – he claimed that the herders could slaughter much more efficiently than his company would be able to do. To this can be added that the herders – when they are allowed to slaughter themselves – utilize virtually every fiber of the animal: an important consideration in times of ecological awareness.

Reindeer meat has every possibility to become a luxury food, as it used to be in Oslo 50 years ago when the steaks still had the traditional quality. An indigenous cookbook supported by the Arctic Council won the 22nd annual Gourmand World Cookbook for “Best Book of the Year in All Categories” in 2018, and in 2020 The New York Times article highlighted reindeer meat as follows: “Reindeer meat is lean and as mild as veal, clean and delicate, tasting of pastures and mountain springs.”

If the herders themselves again can get control over the value chain, there are many possibilities for marketing this healthy and exotic product. In the Swiss and Italian Alps, dried meat – called, respectively, Bündnerfleisch and Bresaola – command high prices. In a test with Italian cooks and restaurant owners, dried Norwegian reindeer meat received an enthusiastic welcome.

Reindeer herding is a traditional, indigenous family-based way of life, based on utilization of marginal resources under cyclicality and ever-changing natural conditions. If the Norwegian government lets go of its basically ‘colonial’ practices and gives the most profitable part of the value chain back to the herders, reindeer herding can have a great and sustainable future.

Notes

- 1.

Reinert’s later studies of the much better reindeer management in Sweden and Finland only contributed to this feeling.

- 2.

One of the authors, Reinert, studied under Murra at Cornell University.

- 3.

In this sense, the Sámi follow the advice of Francis Bacon in his Novum Organum (1620): “Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed.”

- 4.

In fact, it has been found that the weight of reindeer calves in the southern areas varies according to the same pattern as does the number of animals in Finnmark.

- 5.

Formally, the Sámi issues are under the Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, but the key economic issues for the main economic activity of reindeer herding are under the Ministry of Agriculture and Food (LMD).

- 6.

A previous employee at the Norwegian Ministry of Fisheries wisely suggested that reindeer herding should be transferred from the Ministry of Agriculture to the Ministry of Fisheries, a ministry where the management of a highly variable resource base was at the core of their activity.

References

Bacon, F. (1620). Novum Organum. Apud Joannem Billium.

Benjaminsen, T. A., Eira, I. M. G., & Sara, M. N. (Eds.). (2016). Samisk reindrift, norske myter. Fagbokforlaget.

Bjørklund, I. (2004). Saami pastoral Society in Northern Norway: The National Integration of an indigenous management system. In D. Anderson & M. Nuttall (Eds.), Cultivating arctic landscapes. Berghahn Books.

Bjørklund, I., & Eidheim, H. (1999). Om reinmerker – kulturelle sammenhenger og norsk jus i Sapmi. In I. Bjørklund (Ed.), Norsk ressursforvaltning og Sámiske rettsforhold. Ad Notam.

Eira, I. M. G. (2012). Muohttaga Jávohis Giella: Sámi Árbevirolaš Máhttu Muohttaga Birra Dálkkádatrievdanáiggis (The silent language of snow: Sámi traditional knowledge of snow in times of climate change). University of Tromsø.

Eira, I. M. G., Mathiesen, S. D., Oskal, A., & Hanssen-Bauer, I. (2018). Snow cover and the loss of traditional indigenous knowledge. Nature Climate Change, 8, 928–931.

Heikkilä, L. (2006). The comparison in indigenous and scientific perceptions of reindeer management. In Forbes et al., pp. 73–93.

Lie, I., & Nygaard, V. (2000). Reindriftsforvaltningen: En evaluering av organisasjon og virksomhet. NIBR Prosjektrapport 16.

Magga, O. H., Oskal, N., & Sara, M.N. (2001). Dyrevelferd i Sámisk Kultur. Report by Sámi allaskuvla/Sámisk høgskole [http://www.regjeringen.no/nb/dep/lmd/dok/rapporter-og-planer/rapporter/2001/dyrevelferd-i-Sámi sk-kultur.html. Accessed 21 Aug 2012].

Montesquieu. (1748/1977). In D. W. Carrithers (Ed.), The spirit of the laws: A compendium of the first English edition. University of California Press.

Murra, J. (1975). El «control vertical» de un máximo de pisos ecológicos en las sociedades andinas. In J. Murra (Ed.), Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino. Lima.

NRK Sápmi. (2020). Ordførere med desperat rop om hjelp til landbruksministeren. News story including referred letter, published March 23, 2020, by the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, Sámi News, NRK Sápmi. https://www.nrk.no/sapmi/34-ordforere-med-desperat-rop-om-hjelp-til-landbruksministeren-1.14957066

Oskal, A., Turi, J. M., Mathiesen, S. D., & Burgess, P. (2009). EALÁT. Reindeer herders voice: Reindeer herding, traditional knowledge and adaptation to climate change and loss of grazing lands.

Paine, R. (1977). The white Arctic – Essays on tutelage and ethnicity. Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Pogodaev, M., & Oskal, A. (2015). Youth – The future of reindeer herding peoples. Arctic council ministerial meeting deliverable report, by sustainable development working group, Association of World Reindeer Herders and International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry. Final report from the Arctic council EALLIN reindeer herding youth project 2012–2015, 123 pages. International Centre for Reindeer Husbandry, Guovdageaidnu/ Kautokeino, Norway.

Polanyi, K. (1944). The great transformation. Beacon Press.

Polanyi, M. (1966). The tacit dimension. Routledge.

Reinert, E. (2002). Reinkjøtt: Natur, Politikk, Makt og Marked. SND.

Reinert, E. (2006). The economics of reindeer herding. Sámi entrepreneurship between cyclical sustainability and the powers of state and oligopoly. British Food Journal, 108, 522–540.

Reinert, R. (2007). How rich countries got rich and why poor countries stay poor (Vol. 94). Constable.

Reinert, E., Reinert, H., Mathiesen, S., Aslaksen, I., Eira, I., & Turi, E. I. (2009). Adapting to climate change in reindeer herding – The nation-state as problem and solution. In I. Lorenzoni (Ed.), Living with climate change: Are there limits to adaptation? Cambridge University Press.

Reinert, H., Mathiesen, S., & Reinert, E. (2010). Climate change and pastoral flexibility. In G. Winther (Ed.), The political economy of northern regional development. Nordic Council of Ministers.

Sara, M. N. (2001). Reinen – et Gode fra Vinden. Davvi Girji.

Troll, C. (1931). Die geographische Grundlage der Andinen Kulturen und des Inkareiches. Ibero-Amerikanisches Archiv, 5, 1–37.

Troll, C. (1966). Ökologische Landschaftsforschung und vergleichende Hochgebirgsforschung. Steiner.

Turi, E. I. (2016). State steering and traditional ecological knowledge in reindeer herding governance: Cases from Western Finnmark, Norway and Yamal, Russia. Umeå University.

Tyler, N. J. C., Turi, J. M., Sundset, M. A., Bull, K. S., Sara, M. N., Reinert, E., Oskal, N., Nellemann, C., McCarthy, J. J., Mathiesen, S. D., Martello, M. L., Magga, O. H., Hovelsrud, G. K., Hanssen-Bauer, I., Eira, N. I., Eira, I. M. G., & Corell, R. W. (2007). Sámi reindeer pastoralism under climate change: Applying a generalized framework for vulnerability studies to a sub-arctic social-ecological system. Global Environmental Change, 17, 191–206.

Veblen, T. (1919). The vested interests and the state of the industrial arts. Huebsch.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reinert, E.S., Oskal, A. (2024). Reindeer Herding in Norway: Cyclicality and Permanent Change vs. Governmental Rigidities. In: Mathiesen, S.D., Eira, I.M.G., Turi, E.I., Oskal, A., Pogodaev, M., Tonkopeeva, M. (eds) Reindeer Husbandry. Springer Polar Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42289-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-42289-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-42288-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-42289-8

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)