Abstract

This chapter explores the participation of animal welfare civil society organisations (CSOs) in the European Parliament’s (EP’s) public hearings and in the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals to reveal who gets a seat at the table when EU parliamentarians consult civil society on animal welfare policies. Theorising the EP as a Strategic Action Field (SAF), animal welfare CSOs invited to official EP public hearings are conceptualised as incumbents, while animal welfare CSOs invited to unofficial Intergroups are perceived as challengers. Drawing on an original sample that covers 84 Intergroup meetings and 43 EP public hearings during the 8th and ongoing 9th EP, this chapter shows how animal welfare organisations challenge established civil society practices in the EP by using the Intergroup as a venue to facilitate cooperation, resource concentration, and access to political elites beyond official parliamentary structures.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- civil society elites

- challengers

- incumbents

- European Parliament

- Eurogroup for Animals

- Strategic Action Fields

Introduction

The European Union (EU) has the ‘most comprehensive and advanced animal welfare legislation in the world’ although animal welfare does not fall within its exclusive competence (Simonin & Gavinelli, 2019, p. 68). EU animal welfare legislation is developed within the framework of EU policies ‘where the EU has the legal base to act’ such as in agriculture, fisheries, or the internal market (Simonin & Gavinelli, 2019, p. 60). Most of the legislation covers the welfare of ‘food producing animals and […] animals used for experimental purposes’ (European Commission, 2020, p. 1).

As a result, animal welfare is a fiercely contested policy area that is shaped by the interests of various individual and collective actors from adjacent policy fields such as farmers, consumers, and animal welfare organisations. The recently adopted European Parliament (EP) report on on-farm animal welfare (2022) met major criticism from animal welfare civil society organisations (CSOs) such as the Eurogroup for Animals and Compassion in World Farming for favouring ‘farmers’ economic needs’ in many paragraphs and for ignoring ‘much of the scientific knowledge gained in regard to the welfare of animals’ (Eurogroup for Animals, Compassion in World Farming – EU & Four Paws, 2022, p. 1). As co-legislator, the Parliament plays a crucial role in adopting new EU laws on animal welfare. Thus, it can be an important ally for animal welfare CSOs in pushing for EU animal welfare policies.

In asking who gets a seat at the table when EU parliamentarians consult civil society on animal welfare-related policies, this chapter pursues two aims:

First, it compares two institutional venues for civil society participation and deliberation on animal welfare in the Parliament, namely EP public hearings and the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, to identify which types of civil society actors act as incumbents and challengers in the EP’s animal welfare policy. While EP public hearings are official bodies of the Parliament, the Intergroup constitutes an unofficial grouping that is formed by Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) for the purpose to, among other things, ‘promote contact between parliamentarians and civil society’ (European Parliament, 2019, p. 29).

Second, the chapter aims to show how the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals functions as an arena to gather animal welfare CSOs, to concentrate expertise, and to facilitate access to political elites for animal welfare organisations. In this context, particular attention is paid to the Eurogroup for Animals, a Brussels-based animal welfare CSO that acts as the secretariat of the Intergroup. Regarding this position, the Eurogroup speaks of ‘a position envied by many, […] a unique position to influence the Parliament from within’ (Eurogroup for Animals, 2016, p. 44). Furthermore, it describes itself as a ‘privileged partner of many parliamentarians (MEPs) [who works] hand in hand with all political groups to generate better animal welfare policy and legislation’ (Eurogroup for Animals, 2016, p. 44). These statements point to a potential elite status of the Eurogroup in terms of having a key position in the Intergroup and enjoying privileged access to political elites, which this chapter aims to explore in greater depth.

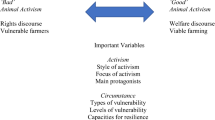

To accommodate these aims, the chapter combines a field-analytical approach in its conceptual framework (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012) with the analysis of 84 agendas of the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals and 43 agendas of EP public hearings during the eighth (2014–2019) and first half of the ongoing ninth European Parliament (2019–2024). The EP is conceptualised as a Strategic Action Field (SAF), that is, as a mesolevel social order (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012). Applying the SAF framework’s key components of incumbents and challengers, those animal welfare CSOs that are invited to EP public hearings are perceived as incumbents. As such they occupy a privileged position in the field as they are invited to a formal EP structure that is part of the official policy deliberations and processes. In contrast, those animal welfare CSOs that participate in Intergroups are conceived of as challengers. They are perceived as occupying a less privileged position in the field as they conduct their deliberations in an institutional setting that is not part of the official EP structure. To gain insight into the sources of power of incumbents and challengers, the organisational capacities of CSOs invited to Intergroup meetings and EP public hearings are also briefly examined.

In line with the field-analytical framework of this chapter, the analysis of civil society consultation on animal welfare in the EP is perceived as an initial struggle for access and voice. It is a struggle for access to institutional venues and thus to political elites in the EP. This struggle is expressed through the institutional regulation of EP Intergroups. It is also a struggle for voice in a policy area that is developed within the context of other EU policies, such as agriculture, and thus is shaped by field struggles in the broader field environment.

The chapter starts with a brief introduction to EP public hearings and Intergroups. Thereafter, the conceptual framework of the Parliament as a SAF is developed. The subsequent analysis examines the participation of animal welfare CSOs in public hearings and in the EP Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals and outlines the organisational capacities of incumbents and challengers. The chapter ends with concluding remarks and reflections on how to define civil society elites’ position in the EP.

Public Hearings in the European Parliament

The EP parliamentary committees frequently hold public hearings to obtain independent expertise and advice on specific topics linked to their legislative, oversight, and appointment activities (Corbett et al., 2016; Díaz Crego & Del Monte, 2021). In these contexts, hearings fulfil various purposes, for example, epistemic, coordinative, and participatory functions (Coen & Katsaitis, 2019). During the eighth EP, 585 public hearings were organised by the parliamentary committees (Sabbati, 2019). According to Ripoll Servant (2018, p. 142), public hearings encourage a ‘broader dialogue’ between parliamentarians, experts, and civil society ‘than one-to-one meetings with selected groups’.

For CSOs, legislative expert hearings provide an opportunity to present their views and expertise to key EU decision-makers, and thus to be part of ‘the evidence-gathering process that prepares the ground for a report’ (Corbett et al., 2016, p. 186). However, the participation in expert hearings requires prior invitation by the parliamentary committee or rather the committee’s secretariat that oversees the organisation of expert hearings (European Parliament, 2003/2014). Thereby, a parliamentary committee may invite ‘a maximum of 16 guests each year whose expenses will be covered’ (European Parliament, 2003/2014, p. 1).

Because animal welfare is predominantly discussed within the scope of the EU’s agricultural policy (though not exclusively), the parliamentary committee on Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI) and its public hearings are of particular interest to animal welfare CSOs. Therefore, the analysis in this chapter focuses on the 25 AGRI hearings of the eighth EP and the 18 AGRI hearings of the current ninth EP.

Intergroups in the European Parliament

Intergroups have existed since the early 1980s in the EP. They are unofficial cross-party, cross-committee groupings that gather MEPs across political groups and parliamentary committees, representatives of other EU institutions (e.g., the European Commission), and civil society and interest groups in their meetings. The current ninth EP (2019–2024) registered 27 Intergroups dealing with issues such as animal welfare, climate change, disability, trade unions, and urban areas, to name just a few.Footnote 1 In the literature, Intergroups have been analysed as informal legislative membership organisations (Ringe et al., 2013), as ‘more or less strong policy networks’ (Nedergaard & Jensen, 2014, p. 9), and as bridging social capital of EU parliamentarians (Landorff, 2019).

In response to concerns about Intergroups being too close to certain lobby groups (Corbett et al., 2016), the Parliament established in 1999 internal rules governing the establishment, operation, and financial declarations of Intergroups (European Parliament, 1999/2012). These rules define Intergroups as not being ‘organs of Parliament’ (European Parliament, 1999/2012, p. 1). Consequently, Intergroups may not express the opinion of the EP (European Parliament, 1999/2012). Furthermore, the regulation entails that Intergroups must seek their (re)establishment as an official EP Intergroup at the beginning of each parliamentary term. The official recognition as an EP Intergroup requires the support of at least three political groups and comes with the provision of technical facilities (e.g., rooms, interpreters, and translation facilities) for Intergroup meetings by the political groups. Due to the regulation, the number of EP Intergroups is limited. Likewise, the themes on which Intergroups are established are subject to change because they need to align with the policy priorities of the political groups. Hence, as a venue for civil society participation and deliberation Intergroups are dependent on the political groups in the Parliament.

The Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals

The Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals exists since 1983 (Corbett et al., 2016, p. 248) and is one of the oldest Intergroups of the EP. The Intergroups ‘Disability’, ‘Minority’, ‘Extreme Poverty’, and ‘Trade Union’ were established in the early 1980s and are still active in the ninth EP (Landorff, 2019). At the beginning of the ninth parliamentary term, 99 MEPs were registered as members of the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals (European Parliament, n.d.).

The Intergroup meets monthly for a one-hour meeting during the Parliament’s plenary sessions in Strasbourg, usually on a Thursday morning.Footnote 2 On average more than 20 MEPs attended Intergroup meetings at the end of 2019 (Eurogroup for Animals, 2020, p. 10). The Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals covers a broad range of animal welfare issues such as animal welfare during transport, animal welfare in experiments and medical research, animal welfare labelling, the welfare of companion animals, and cage-free farming (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, n.d.). Thereby, the Intergroup functions as a ‘forum for debate and actions’ on animal welfare-related legislation (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 1). Its members work on parliamentary reports (e.g., the report on organic production and labelling of organic products or the implementation report on on-farm animal welfare), resolutions (e.g., on a new animal welfare strategy for 2016–2020), and amendments and parliamentary questions to the plenary (Eurogroup for Animals, 2016, p. 20; Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, n.d.).

Among the Intergroups of the ninth Parliament, the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals represents one of the most formalised groups in terms of its organisational structure. It is chaired by a president and several vice-presidents, has a secretariat, and follows its own rules of procedure that guide the actions of the Intergroup (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a). As of 2022, it comprised six ad hoc working groups covering, for instance, animal transport, animals in science, and cage-free farming (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, n.d.).

The Eurogroup for Animals

The Eurogroup for Animals presents itself as the ‘only pan-European animal advocacy organisation’ (Eurogroup for Animals, 2019, p. 2). It was founded in 1980 on the initiative of the UK-based Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty for Animals and ‘similar national societies’ (Corbett et al., 2016, p. 248). At the end of 2021, the Eurogroup represented over 80 animal advocacy organisations in 25 EU member states and several non-EU countries (Eurogroup for Animals, 2022, p. 56). The Eurogroup’s portfolio covers five policy areas, among them trade and animal welfare, animals in science, and farm animals. These are covered by 15 (out of 34) staff members as of May 2022 (Eurogroup for Animals, 2022, pp. 45–46).

The Eurogroup has served as the Intergroup’s secretariat since 1983 and thus draws on nearly 40 years of experience in liaising with MEPs in the Intergroup (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019b). As its secretariat, the Eurogroup is responsible for ‘administrative, organisational, and advisory tasks’ (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 3). These include, for instance, the organisation of the monthly meetings in Strasbourg, the invitation of guests, the preparation and distribution of the meeting agendas, the coordination of Intergroup initiatives, and regular updates of the Intergroup website (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 3).

The European Parliament as a Strategic Action Field for Animal Welfare CSOs

Inspired by field-analytical approaches in EU and EU civil society studies (e.g., Georgakakis & Rowell, 2013; Johansson & Kalm, 2015; Johansson & Uhlin, 2020; Kauppi, 2011; Lindellee & Scaramuzzino, 2020; Michel, 2013), this chapter employs the notion of Strategic Action Fields (SAFs) as a heuristic device to construct the Parliament as a ‘meso-level social order’, that is, as a social arena that is shaped by competition and cooperation between collective actors (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 9).

In this way, the chapter applies an institutionalist-inspired approach to field analysis as opposed to an orthodox habitus-inspired field approach (for a good discussion, see Gengnagel, 2014). Its strong and parsimonious focus on the strategic actions of individual and collective actors, on the interplay of cooperation and competition within and across the field, and its account of the broader field environment, makes the SAF framework suitable for the analysis of EP institutional settings. The framework is utilised to map and identify the positions of animal welfare CSOs within the EP and to disclose processes of resource accumulation and concentration that are fostered through the cooperation of animal welfare CSOs in different parliamentary venues.

As a SAF, the Parliament is composed of different sets of actors ‘who can be generally viewed as possessing more or less powers’ (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 11). Thereby, two types of actors are distinguished, namely incumbents and challengers. Incumbents are those actors ‘who occupy privileged positions within the field in terms of ‘material and status reward’ and who wield disproportionately influence within the SAF (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 13). Challengers are those actors who ‘occupy less privileged positions’ within the SAF and therefore exert less influence over the functioning of the field (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 13). Drawing on positional approaches to civil society elite identification (Johansson & Lee, 2015; Lindellee & Scaramuzzino, 2020; Mills, 1956/2000), the privileged position of incumbents shall be defined as an elite position that is tied to a formal and official organisational position in the Parliament. Hence, those civil society actors invited to official public hearings are defined as incumbents. As such, they are officially recognised as partners to provide expertise and opinions on animal welfare-related policies and legislation. Their position, resources, and powers are institutionally and formally embedded in the organisation, that is, the EP. In contrast, those civil society actors who are invited to Intergroup meetings are defined as challengers whose powers and resources are not formally embedded in the EP.

Incumbents and challengers interact with each other based on shared understandings of ‘what the purpose of the field is’, of what the rules are that govern legitimate actions within the field, and of their relationships to others in the field (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 9). Thus, they share the understanding of the EP’s role as co-legislator in EU animal welfare policies. Both understand the tactics and strategies that are possible and legitimate in the Parliament with regard to civil society consultation and participation. In other words, they understand that official civil society consultation takes place in the EP public hearings as part of recognised and established formal EP policy processes, while civil society consultation in EP Intergroups is recognised by the Parliament though not as part of formal EP policy discussions. Both groups understand how their position in EP public hearings and Intergroups relate to each other and to other collective and individual actors in the SAF (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 11). This means that incumbents and challengers know who their friends and competitors are and where these actors are positioned in the Parliament.

Despite their less privileged positions as challengers within the parliamentary SAF, they ‘can be expected to conform to the prevailing order’ of the SAF (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012, p. 13); that is, that civil society consultation is practiced in official EP public hearings, while EP Intergroups serve as unofficial venues for civil society deliberation. Challengers conform to the order that EP Intergroups are deprived of the right to speak in the name of the Parliament and are not part of the legislative process. However, as challengers they also confront the established working order of the SAF in terms of how, where, and with whom interactions and deliberations on animal welfare policies are practiced in the EP.

Who Is Involved? Public Hearings of the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development

In the eighth EP (November 2014–March 2019), the AGRI committee conducted 25 hearings (European Parliament, 2014–2019). The hearing on ‘Cloning of animals for farming purposes’ was the only hearing explicitly dedicated to animal welfare (see Table 13.1). It was jointly organised with the parliamentary committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety. Additionally, the hearing on ‘European – Level playing field: state of implementation of the EU agricultural legislation in different Member States’ in April 2016 featured a presentation on animal welfare and environmental requirements in the European pig sector (European Parliament, 2016; see Table 13.1). Not a single animal welfare CSO was invited to any of the 25 AGRI public hearings of the eighth Parliament. In the first half of the ongoing ninth EP (November 2019–March 2022), the AGRI committee has organised 18 hearings (European Parliament, 2019–2022). Two hearings in June and September 2021 were explicitly dedicated to animal welfare (Table 13.1).

The analysis of AGRI hearings shows that animal welfare is one topic among many on which the committee organises its public hearings. Overall, AGRI hearings cover the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy and global agricultural policies. Hearings are organised on the EU’s dairy and sugar markets, the EU’s Forest Strategy, and its Farm to Fork Strategy.Footnote 3 All subjects, including animal welfare, are discussed in relation to the EU’s agricultural policy. This finding is interpreted as reflecting the overall division of powers within EU animal welfare policies. As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, EU animal welfare legislation is developed within the context of policies where the EU has the legal right to act, that is, within the EU’s agricultural, environmental, or internal market policies. Hence, animal welfare denotes a dominated policy field. As a dominated policy area, animal welfare is not discussed in its own right in the Parliament, that is, in a separate, stand-alone parliamentary committee, but as a sub-theme of agriculture, environment, or the internal market.Footnote 4 As a result, civil society actors advocating animal rights need to compete for a voice and for access to the EP legislative agenda.

Conceptualising those animal welfare CSOs that attend official EP hearings as incumbents shows that the globally operating, UK-based charity Compassion in World Farming is the only animal welfare organisation invited to these hearings (Table 13.1). Compassion in World Farming campaigns for the end of extensive farming practices and advocates, among other things, for a sustainable food system (European Commission, 2022). In the hearing in September 2021, Compassion in World Farming was represented by the head of its Brussels branch, Olga Kikou (European Parliament, 2021). Kikou outlined in her presentation citizens’ expectations regarding the welfare of farm animals, current animal welfare policies in the EU, and Compassion in World Farming’s demands concerning changing food systems, the caging of animals, live exports, etc. (Compassion in World Farming, 2021).

As outlined in Table 13.1, a broad group of stakeholders is consulted for expertise and opinions on animal welfare policies in AGRI hearings. These include representatives of the responsible Directorate-Generals of the European Commission (e.g., Agriculture, Health and Food Safety), the EP, national and EU research/academic institutions, representatives of the European farmers’ lobby (e.g., the European farmers and European agri-cooperatives, COPA-COGECA), EU member state authorities, consumer group organisations (e.g., the European Consumer Organisation, BEUC), and animal welfare CSOs such as Compassion in World Farming. While representatives of the farmers’ lobby feature in every hearing, animal welfare CSOs have only been invited once, at the meeting in September 2021. Measured in terms of attendance, animal welfare CSOs are valued as consultative partner as much as consumer organisations, though not as much as farmers’ organisations. From the perspective of animal welfare CSOs, Compassion in World Farming is said to have an elite position because it is the only animal welfare CSO invited to an official policy consultation process.

Overall, it is argued that the organisation and composition of AGRI public hearings on animal welfare reflect the power structures and dominant actors in EU animal welfare policies, as well as the evidence-based policy-making approach of the EU. As a result, consultations on animal welfare in EP AGRI public hearings are primarily shaped by representatives of the European Commission, the farmer’s lobby, and scientific experts.

Who Is Involved? The Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals

The organisation of Intergroup meetings and the invitation of guest speakers falls under the responsibility of the Intergroup secretariat, that is, the Eurogroup for Animals (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 3). The Intergroup’s rules of procedure outline the qualities of a good speaker. Accordingly, ‘speakers should possibly be experts who are able to inspire and to engage in lively in-depth discussions with MEPs’ (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 16). Thus, expert knowledge, good presentation and communication skills are valued by the Intergroup’s organisers. Moreover, the rules refer to ‘EU officials or representatives from NGOs who cover their own expenses’ (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a, p. 16). Thus, guests need to have sufficient economic resources to cover their participation in Intergroup meetings in Strasbourg. In contrast, the expenses for attending EP public hearings are covered by the parliamentary committees (European Parliament, 2003/2014, p. 1). The Intergroup as such lacks its own independent budget (Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals, 2019a).

Based on these criteria, 153 speakers were invited to 56 Intergroup meetings throughout the eighth Parliament (September 2014–March 2019). On average, the Intergroup hosted two to three guests during their meetings. Out of the 153 invitees, 73 speakers represented 33 different animal welfare CSOs (incl. wildlife conservation organisations), 33 speakers were MEPs, and 18 speakers were European Commission representatives.Footnote 5 Thus, representatives of animal welfare CSOs constitute the largest individual social group among the invited guests.

Among participating animal welfare CSOs, representatives of the Eurogroup for Animals gave 22 presentations at 22 meetings. Thus, the Eurogroup is the animal welfare CSO with the most interventions. In distant second, Compassion in World FarmingFootnote 6 follows with five presentations, and World Horse Welfare and Four PawsFootnote 7 follow with four and three presentations, respectively, during the 56 Intergroup meetings.

In the first half of the ninth parliamentary term, that is, from September 2019 to July 2022, the Intergroup has organised 28 monthly meetingsFootnote 8 to which 79 guests were invited. Of these, 32 invitees spoke on behalf of 21 different animal welfare CSOs, while academics/scientistsFootnote 9 and European CommissionFootnote 10 representatives had 13 presentations each, followed by MEPs with 11 presentations.

Among attending animal welfare CSOs, the Eurogroup for Animals presented seven times, while Compassion in World FarmingFootnote 11 gave four presentations. Four PawsFootnote 12 and Cruelty Free Europe gave two presentations each. Together these four CSOs are the most invited individual animal welfare CSOs in the Intergroup.

Overall, these figures show that the Intergroup serves as a venue for animal welfare CSOs. In contrast to AGRI public hearings in which animal welfare CSOs play a marginal role, animal welfare CSOs are the largest social group among invited speakers in the Intergroup. The Eurogroup for Animals stands out as the most frequently speaking animal welfare CSO in the eighth and ninth parliamentary term. This position is strengthened when considering the presentations by Eurogroup members. In the eighth EP, Eurogroup members delivered 28 presentations. These included presentations by Compassion in World Farming and Four Paws. Both are Eurogroup members. Overall, the Eurogroup and its members delivered two-thirds of all CSO presentations in the Intergroup from 2014 to 2019 (49 out of 73 interventions).

In the first half of the 9th EP, Eurogroup members delivered 14 presentations, including interventions by Compassion in World Farming and Four Paws. In other words, 21 out of 79 presentations in the Intergroup were provided by the Eurogroup and its members. In this way, the Eurogroup provides its members with a platform to voice their interests to MEPs and representatives of the European Commission and provides them with access to political elites.

Organisational Capacities of Incumbents and Challengers

To engage in EP public hearings and Intergroup meetings requires incumbents and challengers to have sufficient organisational capacities. A good indicator to assess the professional resources of organisations is the number of staff available for EU lobbying. Financial resources can be assessed in terms of available lobbying costs. Moreover, being a membership/umbrella organisation and having one’s headquarters in Brussels are interpreted as an organisational source of power. A head office in Brussels implies being close to the EU institutions. However, while EP public hearings are organised in Brussels, the meetings of the Intergroup take place in Strasbourg, France. Here, a head office in Brussels is not necessarily of advantage. For the Eurogroup and participating CSOs, additional time and financial resources are required to attend Intergroup meetings in Strasbourg.

The comparison of the organisational capacities shows the dominance of the union of farmers and agri-cooperatives in the EU (COGECA) and the European Consumer Organisation (BEUC) in terms of lobbying costs, full-time employees available for EU lobbying, the number of EP pass holders, and the number of meetings with the European Commission (see Table 13.2). The Eurogroup for Animals ranks third in terms of lobbying costs, EP passes, and meetings with the Commission. Thus, it outranks panellists on AGRI public hearings, including the European Council of Young Farmers (CEJA) and Compassion in World Farming Brussels (Table 13.2).

Among the animal welfare CSOs that are invited to the Intergroup, the Eurogroup for Animals stands out as the only membership organisation. Thus, the Eurogroup draws on its representational mandate that it has been given by its members, among these are Compassion in World Farming and Vier Pfoten International (Four Paws). Although Compassion in World Farming has more full-time staff available for EU lobbying than the Eurogroup, this is not reflected in the number of registered EP pass holders or meetings with the European Commission. Despite having fewer staff members available for EU lobbying, the Eurogroup has more frequent access to and interactions with EU decision-makers. In addition to its engagement in the EP Intergroup, the Eurogroup has been a member of ‘36 expert consultative bodies of the European Commission’ as of 2019 (Eurogroup for Animals, 2020, p. 12). Overall, the Eurogroup outranks both of its fellow animal welfare CSOs from the Intergroup in terms of lobbying costs, EP access passes, and meetings with the Commission.

The invitation of Compassion in World Farming Brussels to EP public hearings and the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals can be interpreted as a privileged position. Judging from the financial resources and the number of staff, this privileged position might rather be based on Compassion in World Farming’s professional expertise on farm animals, and the fact that policies on farm animals fall within the EU’s agriculture policy, than on its economic resources.

The comparison shows that the Eurogroup can challenge animal welfare CSOs that are invited to EP public hearings on the grounds of lobby costs, its membership base, meetings with the European Commission, and EP accreditation passes. However, it cannot compete with representatives of the EU farmer’s lobby and consumers’ organisation. Because EP public hearings on animal welfare are less frequently organised than Intergroup meetings on animal welfare and consequently feature less participation by animal welfare CSOs, the comparison is hampered.

However, this chapter argues that the Eurogroup fosters an accumulation and concentration of policy expertise in the Intergroup that is valued by EU parliamentarians and representatives of the European Commission given their regular attendance in the Intergroup. In 20 out of 29 Eurogroup presentations during the eighth and ninth EP, either an MEPFootnote 13 or representative of the European Commission was also present on the panel. Hence, a direct exchange of views and expertise between the Eurogroup and EU decision-makers takes place in the Intergroup. For this exchange, the Eurogroup draws strategically on its members and its own professional programme staff to provide input on EU legislative dossiers, such as the EU Regulation on Invasive Alien Species, the implementation of the EU’s Zoo Directive, or the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy. With regard to the EP’s implementation report on on-farm animal welfare, the Eurogroup used the Intergroup to present its demands concerning the inclusion of a five-domain model on animal well-being and species-specific rules in the AGRI-report as well as the tackling of non-compliance issues.Footnote 14 In this way, the Eurogroup and its members are also part of an ‘evidence-gathering process’, similar to the processes observed at the level of EP public hearings, that accompanies the preparation of EP legislative reports.

Conclusion

In asking who gets a seat at the table, this chapter shows that animal welfare CSOs play a marginal role when EU parliamentarians consult civil society on animal welfare in official AGRI public hearings. Compassion in World Farming is the only animal welfare CSO to receive the status of a recognised partner in an official EP consultation process, and this is interpreted as an incumbent and elite position from the perspective of animal welfare CSOs. However, the analysis shows that animal welfare CSOs predominantly engage as challengers in unofficial groupings, such as the Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals.

In line with the SAF framework, this engagement is interpreted as a strategic action of animal welfare CSOs that is necessitated by the overall power structure of EU animal welfare politics. As a dominated policy field, animal welfare plays a subordinate role on the EP’s legislative agenda. Thus, it is granted limited time and space within the EP’s official organisational structures. This chapter shows how animal welfare CSOs make use of the flexible and dynamic nature of the EP as a SAF to foster the emergence of new organisational practices and of alternative social spaces for civil society beyond the official parliamentary practices for civil society consultation. Admittedly, these social spaces are denied the recognition as an official EP structure. However, this chapter also shows that the status of an unofficial grouping does not necessarily result in a less privileged position within the SAF.

On the contrary, as a collective actor the Intergroup facilitates the concentration and cooperation of animal welfare CSOs that goes hand in hand with the accumulation, pooling, and exchange of policy expertise and the provision of access to political elites. While individual animal welfare CSOs cannot compete with consulted stakeholders in official EP public hearings in terms of their organisational capacities, their expertise is valued and demanded by EU parliamentarians and representatives of the European Commission. The regular presence of these political elites in Intergroup meetings confers status and recognition to those civil society actors active in the Intergroup irrespective of the unofficial status of the Intergroup and their organisational capacities.

Thus, the Eurogroup for Animals occupies a pivotal role in the Intergroup. As the Intergroup’s secretariat and the animal welfare organisation with the most individual presentations during Intergroup meetings, the Eurogroup occupies an incumbent position, and thus an elite position, within the Intergroup. The finding that Compassion in World Farming occupies both an incumbent and challenger position within the SAF, as an invited speaker to EP public hearings and the Intergroup, might be a sign of a civil society actor moving from a challenger to incumbent position or of a civil society actor occupying multiple positions within the SAF. Further research is needed to draw a final conclusion on this observation.

As a result of the analysis, this chapter suggests discussing the term of civil society elites not solely based on civil societies’ embeddedness in and ties to formal and official organisational positions in the EP, but with regard to their possession of and control over valued policy expertise, as well as the status and recognition that is conferred to them on the basis of regular interactions with political elites. Future research should focus on how the possession and access to valued resources is used by these CSOs to influence EP policymaking on animal welfare.

Overall, this chapter provides an important contribution to the discussion of civil society’s position in EP policymaking and its access to political elites. It provides original insights into the establishment of alternative, and potentially elitist, arenas of civil society deliberation and networking beyond the official parliamentary structures that are based on processes of resource pooling and resource concentration.

Notes

- 1.

For an overview of all 27 Intergroups of the ninth EP, see https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/en/organisation-and-rules/organisation/Intergroups (Accessed: 14 July 2022).

- 2.

The move to online meetings in April 2020 has occasionally extended the meetings to up to two hours.

- 3.

For a full overview of topics, see the website of the EP committee on Agriculture and Rural Development.

- 4.

However, the establishment of a Committee of Inquiry on the Protection of Animals during Transport during the ninth EP can be interpreted as animal welfare gaining status on the parliamentary agenda, see also Eurogroup for Animals (2021, p. 9).

- 5.

Including European Commissioners.

- 6.

Represented by its EU (3) and international/UK branch (1).

- 7.

EU and Austrian office.

- 8.

Additionally, two side-events and a webinar were organised. Between April 2020 and March 2022 meetings were conducted online.

- 9.

From universities and research institutes.

- 10.

Including European Commissioners.

- 11.

Represented by its EU (1) and international branch/UK (3).

- 12.

Represented by staff members of its European policy office in Brussels.

- 13.

Also, in their function as rapporteurs.

- 14.

See meeting in July 2021. Available at: https://www.animalwelfareintergroup.eu/files/default/meetings-events/agendas/en/AGENDA%20378%20Implementation%20report%20on-farm%20animal%20welfare%20.pdf (Accessed 27 October 2022).

References

Coen, D., & Katsaitis, A. (2019). Between Cheap Talk and Epistocracy: The Logic of Interest Group Access in the European Parliament’s Committee Hearings. Public Administration, 97(4), 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12406

Compassion in World Farming. (2021). Connecting Animal Welfare to Citizens’ Voices, presentation by Olga Kikou, 30 September 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/240232/Kikou_AGRI%20Hearing%20presentation.pdf. Accessed 22 July 2022.

Corbett, R., Jacobs, F., & Neville, D. (2016). The European Parliament (9th ed.). John Harper Publishing.

Díaz Crego, M., & Del Monte, M., (2021). Committee Hearings in the European Parliament and US Congress. European Parliament Research Service (PE 696.172), July 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/696172/EPRS_BRI(2021)696172_EN.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals. (2016). Annual Report 2015. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2021-12/AnnualReport2015.pdf. Accessed 18 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals. (2019). Annual Report 2018. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2021-12/AnnualReport2018.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals. (2020). Annual Report 2019. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2021-12/AnnualReport2019.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals. (2021). Annual Report 2020. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2021-12/Eurogroup%20for%20Animals%20Annual%20Report%202020%20Final.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals. (2022). Annual Report 2021. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2022-06/1718%20Annual%20Report%202021%20Eurogroup%20for%20Animals_online_singles_1.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2022.

Eurogroup for Animals, Compassion in World Farming – EU, and Four Paws. (2022). RE: Open Letter Regarding the Plenary Vote on the AGRI Implementation Report on On-Farm Animal Welfare, 10 February. https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/files/eurogroupforanimals/2022-02/2022_02_10_open_letter_decerle_report.pdf. Accessed 05 July 2022.

European Commission. (2020). Fitness Check Roadmap. https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-05/aw_fitness-check_roadmap.pdf. Accessed 25 Sept 2022.

European Commission. (2022). Transparency Register – Search the Register, June to October 2022. https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/consultation/search.do?locale=en&reset=. Accessed June Oct 2022.

European Parliament. (n.d.). About Parliament – Organisation and Rules – Intergroups. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/files/organisation-and-rules/organisation/Intergroups/list-of-members-welfare-and-conservation-of-animals.pdf. Accessed 1 Apr 2022.

European Parliament. (1999/2012). Rules Governing the Establishment of Intergroups Decision of the Conference of Presidents (PE422.583/BUR). http://www.europarl.europa.eu/about-parliament/files/organisation-and-rules/organisation/intergroups/rules-governing-the-establishment-of-integroupes-19991116.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

European Parliament. (2003/2014). Rules on Public Hearings Bureau Decision of 18 June 2003 and Amended by 16 June 2014 (PE 422.597/BUR). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/publications/reg/2003/0001/EP-PE_REG(2003)0001_EN.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2022.

European Parliament. (2014–2019). Committees – Archives - Committees 8th parliamentary term(2014–2019). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/archives/8/agri/events/events-hearings. Accessed 01 July 2022.

European Parliament. (2016). Programme: Hearing on ‘European – Level Playing Field: State of Implementation of the EU Agricultural Legislation in Different Member States. Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development, 25 April 2016. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/101131/programme_EU%20level%20playing%20field.pdf. Accessed 01 July 2022.

European Parliament. (2019). Rules of Procedure. 9th Parliamentary Term, July 2019. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RULES-9-2019-07-02_EN.pdf. Accessed 09 July 2019.

European Parliament. (2019–2022). Committees – Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development – Events – Hearings. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/agri/events/events-hearings. Accessed 01 July 2022.

European Parliament. (2021). Draft PROGRAMME: Hearing on “Animal Welfare: Support, Enablers and Incentives to Reinforce EU Leadership and Guarantee Economic Sustainability for Farmers”, Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development, 30 September 2021. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/239673/Draft%20programme_Animal%20Welfare%20Hearing_final_en.pdf. Accessed 01 July 2022.

European Parliament. (2022). Implementation report on on-farm animal welfare European Parliament resolution of 16 February 2022 on the implementation report on on-farm animal welfare (2020/2085(INI)), P9_TA(2022)0030. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2022-0030_EN.pdf. Accessed 26 Sept 2022.

Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A Theory of Fields. Oxford University Press.

Gengnagel, V. (2014). Transnationale Europäisierung? Aktuelle feldanalytische Beiträge zu einer politischen Soziologie Europas. Berliner Journal für Soziologie, 24, 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11609-014-0252-9

Georgakakis, D., & Rowell, J. (Eds.). (2013). The Field of Eurocracy: Mapping EU Actors and Professionals. Palgrave Macmillan.

Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals. (2019a). Rules of Procedure. https://www.animalwelfareintergroup.eu/files/default/2019-09/Finalised-rules-of-procedure.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2022.

Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals. (2019b). About us. https://www.animalwelfareintergroup.eu/about-us/. Accessed 7 January 2019.

Intergroup on the Welfare and Conservation of Animals. (n.d.). What We Do – Objectives. https://www.animalwelfareintergroup.eu/what-we-do. Accessed 16–27 Oct 2022.

Johansson, H., & Kalm, S. (Eds.). (2015). EU Civil Society: Patterns of Cooperation, Competition and Conflict. Palgrave Macmillan.

Johansson, H., & Lee, J. (2015). Competing Capital Logics in the Field of EU-Level CSOs: ‘Autonomy from’ or ‘Interconnectedness with’ the EU. In H. Johansson & S. Kalm (Eds.), EU Civil Society: Patterns of Cooperation, Competition and Conflict (pp. 61–80). Palgrave Macmillan.

Johansson, H., & Uhlin, A. (2020). Civil Society Elites: A Research Agenda. Politics and Governance, 8(3), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i3.3572

Kauppi, N. (2011). EU Politics. In A. Favell & V. Guiraudon (Eds.), Sociology of the European Union (pp. 150–171). Palgrave Macmillan.

Landorff, L. (2019). Inside European Parliament Politics: Informality, Information and Intergroups. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lindellee, J., & Scaramuzzino, R. (2020). Can EU Civil Society Elites Burst the Brussels Bubble? Civil Society Leaders’ Career Trajectories. Politics and Governance, 8(3), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i3.2995

LobbyFacts. (2022/2019). Search – Lobby Organisation by Name January to April 2019/May to July 2022. https://www.lobbyfacts.eu/search-all#representative-search. Accessed May to Oct 2022.

Michel, H. (2013). EU Lobbying and the European Transparency Initiative: A Sociological Approach to Interest Groups. In N. Kauppi (Ed.), A Political Sociology of Transnational Europe (pp. 53–78). ECPR Press.

Mills, C. W. (1956/2000). The Power Elite. Oxford University Press.

Nedergaard, P., & Jensen, M. D. (2014). The Anatomy of Intergroups. Network Governance in the Political Engine Room of the European Parliament. Policy Studies, 35(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2013.875146

Ringe, N., Victor, J. N., & Carman, C. J. (2013). Bridging the Information Gap: Legislative Member Organizations as Social Networks in the United States and the European Union. University of Michigan Press.

Ripoll Servant, A. (2018). The European Parliament. Red Globe Press.

Sabbati, G. (2019). European Parliament: Facts and Figures. European Parliamentary Research Service (PE 640.146), October 2019. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2019/640146/EPRS_BRI(2019)640146_EN.pdf. Accessed 30 Oct 2022.

Simonin, D., & Gavinelli, A. (2019). The European Union Legislation on Animal Welfare: State of Play, Enforcement and Future Activities. https://www.fondation-droit-animal.org/proceedings-aw/. Accessed 19 Sept 2022.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (project grant M17-0188:1) for the project titled ‘Civil Society Elites? Comparing Elite Composition, Reproduction, Integration and Contestation in European Civil Societies’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Landorff, L. (2024). Who Gets a Seat at the Table? Civil Society Incumbents and Challengers in the European Parliament’s Consultations. In: Johansson, H., Meeuwisse, A. (eds) Civil Society Elites. Palgrave Studies in Third Sector Research. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40150-3_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40150-3_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-40149-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-40150-3

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)