Abstract

Differentiated Instruction has been promoted as a model to create more inclusive classrooms by addressing individual learning needs and maximizing learning opportunities. Whilst differentiated instruction was originally interpreted as a set of teaching practices, theories now consider differentiated instruction rather a pedagogical model with philosophical and practical components than the simple act of differentiating. However, do teachers also consider differentiated instruction as a model of teaching? This chapter is based on a doctoral thesis that adopted differentiated instruction as an approach to establish effective teaching in inclusive classrooms. The first objective of the dissertation focused on how differentiated instruction is perceived by teachers and resulted in the DI-Quest model. This model, based on a validated questionnaire towards differentiated instruction, pinpoints different factors that explain differences in the adoption of differentiated instruction. The second objective focused on how differentiated instruction is implemented. This research consisted of four empirical studies using two samples of teachers and mixed method. The results of four empirical studies of this dissertation are discussed and put next to other studies and literature about differentiation. The conclusions highlight the importance of teachers’ philosophy when it comes to implementing differentiated instruction, the importance of perceiving and implementing differentiated instruction as a pedagogical model and the importance and complexity of professional development with regard to differentiated instruction.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keyword

1 Introduction

Differentiated Instruction (DI) has been promoted as a model to facilitate more inclusive classrooms by addressing individual learning needs and maximizing learning opportunities (Gheyssens et al., 2020c). DI aims to establish maximal learning opportunities by differentiating the instruction in terms of content, process, and product in accordance with students their readiness, interests and learning profiles (Tomlinson, 2017). This chapter is based on a doctoral thesis that adopted DI as an approach to establish effective teaching in inclusive classrooms. This doctoral dissertation consisted of four empirical studies towards the conceptualisation and implementation of DI (Gheyssens, 2020). This chapter summarizes the most important results of this dissertation and includes three parts. First the conceptualisation of DI is discussed. Second, we discuss literature findings regarding the effectiveness of DI. Third, the results of the studies about the implementation of DI are discussed. Finally, based on the previous parts some recommendations for implementation are presented.

2 Conceptualisation of Differentiated Instruction

2.1 Defining Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction (DI) is an approach that aims to meet the learning needs of all students in mixed ability classrooms by establishing maximal learning and differentiating instruction with regard to content, process and product in accordance with student needs in terms of their readiness (i.e., student’s proximity to specified learning goal), interests (i.e., passions, affinities that motivate learning) and learning profiles (i.e., preferred approaches to learning) (Tomlinson, 2014). Whilst DI was originally interpreted as a set of teaching practices or simplified as the act of differentiating (e.g. van Kraayenoord, 2007; Tobin, 2006), it is evolved towards a pedagogical model with philosophical and practical components (Gheyssens, 2020). This model is rooted in the belief that diversity is present in every classroom and that teachers should adjust their education accordingly (Tomlinson, 1999). Tomlinson (2017) states that DI is an approach where teachers are proactive and focus on common goals for each student by providing them with multiple options in anticipation of and in response to differences in readiness, interest, and learning needs (Tomlinson, 2017). From this perspective, differentiation refers to an educational process where students are made accountable for their abilities, talents, learning pace, and personal interests (Op ‘t Eynde, 2004). This means that teachers proactively plan varied activities addressing what students need to learn, how they will learn it, and how they show what they have learned. This increases the likelihood that each student will learn as much as he or she can as efficiently as possible (Tomlinson, 2005). Moreover, DI emphasizes the needs of both advanced and struggling learners in mixed-ability classroom. In more detail, Bearne (2006) and Tomlinson (1999) consider differentiation as an approach to teaching in which teachers proactively adjust curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities and student product so that various student’s needs are satisfied (individuals or small groups) and every student is provided with maximum learning opportunities (in Tomlinson et al., 2003).

2.2 The DI-Quest Model

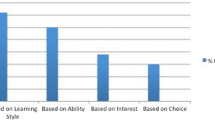

Considering DI as a pedagogical model rather than as a set of teaching strategies became also clear in the validity study of Coubergs et al. (2017) when they tried to measure DI empirically. Their research resulted in the so-called ‘DI-Quest model’, based on the DI-questionnaire the researchers developed for investigating DI. This model pinpoints different factors that explain differences in the adoption of differentiated instruction (Coubergs et al., 2017). It was inspired by the differentiated instruction model developed by Tomlinson (2014), which presents a step by step process demonstrating how a teacher moves from thinking about DI toward implementing it in the classroom. According to this model, the teacher can differentiate content, process, product, and environments to respond to different needs in learning based on students’ readiness, learning profiles, and interests. Tomlinson (2014) also stipulates that, to respond adequately to students’ learning needs, teachers should apply general classroom principles such as respectful tasks, flexible grouping, and ongoing assessment and adjustment. In contrast with Tomlinson’s well-known DI model, which also contains concepts relating to good teaching, the DI-Quest model distinguishes teachers who use DI less often from those who use it more often (Gheyssens et al., 2020c). The DI-Quest model comprises five factors. The five factors are presented in three categories. The key factor, similar to Tomlinson’s (2014) model, is adapting teaching to students’ readiness, interests, and learning profiles. This is the main factor because it represents the ‘core business’ of differentiating: the teachers adapt his/her teaching to three essential differences in learning. The second and third factors represent DI as a philosophy. The fourth and fifth factor represent differentiated strategies in the classroom (Fig. 30.1). Below the figure the different factors are discussed on detail.

2.2.1 Adaptive Teaching

Adaptive teaching illustrates that the teacher provides various options to enable students to acquire information, digest, and express their understanding in accordance with their readiness, interests, and learning profiles (Tomlinson, 2001). Differences in learning profiles are described by Tomlinson and colleagues (2003, p. 129) as “a student’s preferred mode of learning that can be affected by a number of factors, including learning style, intelligence preference and culture.” Applying different learning profiles positively influences the effectiveness of learning because students get the opportunity to lean the way they learn best. Responding to student interests also appears to be related to more positive learning experiences, both in the short and long term (Woolfolk, 2010; Tomlinson et al., 2003). Ryan and Deci (2000) claimed that understanding what motivates students will help develop interest, joy, and perseverance during the learning process. Thus, investing in differences in interests increases learning motivation among students. Taking account of students’ readiness can also lead to higher academic achievement. Readiness focuses on differences arising from a student’s learning position relative to the learning goals that are to be attained (Woolfolk, 2010). When taking students’ readiness into account enables every student to attain the learning objectives in accordance with their learning pace and position (Gheyssens et al., 2021).

2.2.2 Philosophy of DI

The first philosophical factor to consider is the ‘growth mindset’. Tomlinson (2001) addressed the concept of mindset in her DI model by stating that a teacher’s mindset can affect the successful implementation of differentiated instruction (Sousa & Tomlinson, 2011). Teachers with a growth mindset set high goals for their students and believe that every student is able to achieve success when they show commitment and engagement (Dweck, 2006). The second philosophical factor is the ‘ethical compass’. This envisions the use of curriculum, textbooks, and other external influences as a compass for teaching rather than observations of the student (Coubergs et al., 2017; Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). An ethical compass that focuses on the student embodies the development of meaningful learning outcomes, devises assessments in line with these, and creates engaging lesson plans designed to enhance students’ proficiency in achieving their learning goals (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2010). Research on self-reported practices demonstrated that teachers with an overly rigid adherence to a curriculum that does not take students’ needs into account, report to adopt less adaptive teaching practices (Coubergs et al., 2017; Gheyssens et al., 2020c).

2.2.3 Differentiated Classroom Practices

The next factor is the differentiated practice to be explained is ‘flexible grouping’. Switching between homogeneous and heterogeneous groups helps students to progress based on their abilities (when in homogeneous groups) and facilitates learning through interaction (when in heterogeneous groups) (Whitburn, 2001). Given that the aim of differentiated instruction is to provide maximal learning opportunities for all students, variation between homogeneous and heterogeneous teaching methods is essential. Coubergs et al. (2017) found that combining different forms of flexible grouping positively predicts the self-reported use of adaptive teaching in accordance with differences in learning. The final factor in the DI-Quest model is the differentiated practice ‘Output = input.’ This factor represents the importance of using output from students (such as information from conversations, tasks, evaluation, and classroom behaviour) as a source of information. This output of students is input for the learning process of the students themselves by providing them with feedback. But this output is also crucial input for the teacher in terms of information about how students react to his/her teaching (Hattie, 2009). Assessment and feedback are not the final steps in the process of teaching, but they are an essential part of the process of teaching and learning (Gijbels et al., 2005). In this regard, Coubergs et al. (2017) state that including feedback as an essential aspect of learning positively predicts the self-reported use of adaptive teaching.

3 Effectiveness of Differentiated Instruction

Several studies dealing with the effectiveness of DI have demonstrated a positive impact on student achievement (e.g. Beecher & Sweeny, 2008; Endal et al., 2013; Mastropieri et al., 2006; Reis et al., 2011; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019; Valiandes, 2015). However, while recent theories plead for a more holistic interpretation of DI, being a philosophy and a practice of teaching, empirical studies on the impact on student learning are often limited to one aspect of DI, e.g. ability grouping, tiering, heterogenous grouping, individualized instruction, mastery learning or another specific operationalization of DI (e.g. Bade & Bult, 1981; Tomlinson, 1999; Vanderhoeven, 2004; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019). Often studies on DI are also fragmented in studies on ability grouping, tiering, heterogenous grouping, individualized instruction, mastery learning or another specific operationalization of DI (Coubergs et al., 2013; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019). Although effectiveness can be found for most of these operationalisations, overall the evidence is limited and sometimes even inconclusive (e.g. evidence of the benefits on ability grouping). Indeed research indicates that DI has the power to benefit students’ learning. However, this might not always be the case for all students. For example Reis and colleagues demonstrated that at-risk students are most likely to benefit from DI (e.g. Reis et al., 2011). By contrast, experimental research on DI by Valiandes (2015) showed that although the socioeconomic status of students correlated with their initial performance, it had no effect on their progress. This confirmed that DI can maximize learning outcomes for all students regardless of their socioeconomic background. It also depends on how DI is implemented, for example the effects of ability grouping may differ for subgroups of students (Coubergs et al., 2013). A recent review on DI concluded that studies of effectiveness of DI overall report small to medium-sized positive effects of DI on student achievement. However, the authors of this study plead for more empirical studies towards the effectiveness of DI on both academic achievement and affective students’ outcomes, such as attitudes and motivation (Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019).

4 Implementation of Differentiated Instruction

Differentiated instruction is often presented in a fragmented fashion in studies. For example, it can be defined as a specific set of strategies (Bade & Bult, 1981; Woolfolk, 2010) or studies with regard to the effectiveness of DI often focus on specific differentiated classroom actions, rather than on DI as a whole-classroom approach (Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019). Moreover, DI is not only in studies fragmented defined and investigated, DI is also perceived by teachers in a fragmented way (Gheyssens, 2020). For example, using mixed methods, this study explored to what degree differentiated practices are implemented by primary school teachers in Flanders (Gheyssens et al., 2020a). Data were gathered by means of three different methods, which are compared: teachers’ self-reported questionnaires (N = 513), observed classroom practices and recall interviews (N = 14 teachers). The results reveal that there is not always congruence between the observed and self-reported practices. Moreover, the study seeks to understand what encourages or discourages teachers to implement DI practices. It turns out that concerns about the impact on students and school policy are referred to by teachers as impediments when it comes to adopting differentiated practices in classrooms. On teacher level, some teachers expressed a feeling of powerlessness towards their teaching and have doubts if their efforts are good enough. On school level, a development plan was often missing which gave teachers the feeling that they are standing alone (Gheyssens et al., 2020a). Other studies confirm that when beliefs about teaching and learning are different among various actors involved in a school, this can limit DI implementation (Beecher & Sweeny, 2008). However, we know form the DI-Quest model how important a teachers’ mindset is when it comes to implementing DI. In this specific study teachers were asked about both hindrances and encouragements to implement DI. Teachers only responded with hindrances. In addition, flexible grouping, which in theory is an ideal teaching format when it comes to differentiation, occurs often randomly in the classroom without the intention to differentiate. The researchers of this study concluded that teachers do not succeed in implementing DI to the fullest because their mindset about DI is not as advanced as their abilities to implement differentiated practices. These practices, such as flexible grouping for example, are often part of the curriculum. Moreover, also in teacher education programmes pre-service teachers are trained to use differentiated strategies. However, teacher education programmes approach DI mostly again as a set of teaching practices. Teaching a mindset is much more difficult and complicated. This focus on DI as only a practice and as a pedagogical model, like the DI-Quest model demonstrates, leads to partial implementation of DI. DI is then perceived as something teachers can do “sometimes” in their classrooms, rather than a pedagogical model that is embedded in the daily teaching and learning process (Gheyssens et al., 2020a).

In other words, one aspect of DI is often implemented, one specific teaching format is applied, or one strategy is adopted to deal with one specific difference between learning. As a consequence, some aspects will be improved or some students will benefit from this approach, but the desired positive effects on the total learning process of all the students that theories about DI promise, will remain unforthcoming. Below some recommendations are listed to implement DI more as a pedagogical model and less fragmented.

4.1 Importance of the Teachers’ Philosophy

Review studies which investigated the effectiveness and implementation of specific operationalizations of DI (for example grouping) report small to medium effects on student achievement (Coubergs et al., 2013; Smale-Jacobse et al., 2019). Although theories recommend approaching DI as a holistic concept, the effectiveness of such a holistic approach on student learning has, to our knowledge, not yet been investigated. We emphasize the importance of presenting and perceiving DI as a pedagogical model that is regarded as a philosophy of teaching and a collection of teaching practices (Tomlinson, 2017). Thus, DI is considered a pedagogical model that is influenced by teachers’ mindset and one which encourages teachers to be proactive, involves modifying curricula, teaching methods, resources, learning activities and student products in anticipation of, and response to, student differences in readiness, interests and learning profiles, in order to maximize learning opportunities for every student in the classroom (Coubergs et al., 2017; Tomlinson, 2017). In this regard we would also like to emphasize that these modifications do not necessary involve new teaching strategies and extra workload for teachers, but require that teachers shift their mindset and start acting more pro-actively, planned better and be more positive. In a study that investigated the effectiveness of a professional development programme about inclusive education on teachers’ implementation of differentiated instruction, teachers stated that after participating in the programme they did not necessarily adopt more differentiated practices, but they did the ones they used more thoroughly (Gheyssens et al., 2020b). As demonstrated in the DI-Quest model, in order to implement DI as a pedagogical model, it is essential to start with the teachers’ philosophy. However, changing a philosophy does not come about overnight, but rather demands time and patience (Gheyssens, 2020).

4.2 Importance and Complexity of Professional Development

When DI becomes a pedagogical model that consists of both philosophy and practice components, and furthermore demands that teachers have a positive mindset towards DI in order to implement DI effectively, professional development for some teachers is necessary to strengthen their competences and to support them in embedding DI in their classrooms. Depending on the current mindset of the teacher, some will need more support, while for other teachers differentiating comes naturally. However, if we want teachers to implement DI as a pedagogical model and not just as fragmented practices, teachers need to be prepared and supported. Professional development is essential for teachers to respond adequately to the changing needs of students during their careers (Keay & Lloyd, 2011; EADSNE, 2012). However, professional development is also complex. The final study in the dissertation of Gheyssens (2020) investigated the effectiveness of a professional development programme (PDP) aimed at strengthening the DI competences of teachers. A quasi-experimental design consisting of a pre-test, post-test, and control group was used to study the impact of the programme on teachers’ self-reported differentiated philosophies and practices. Questionnaires were collected from the experimental group (n = 284) and control group (n = 80) and pre- and post-test results were compared using a repeated measures ANOVA. Additionally, interviews with a purposive sample of teachers (n = 8) were conducted to explore teachers’ experiences of the PDP. The results show that the PDP was not effective in changing teachers’ DI competences. Multiple explanations are presented for the lack of improvement such as treatment fidelity, the limitations of instruments, and the necessary time investment (Gheyssens et al., 2020b).

We found similar information in other studies. For example Brighton et al. (2005) stated that the biggest challenge for most teachers is that DI questions their previous beliefs. This ties in with our emphasis on teachers’ mindset. To participate in professional development, teachers need to have/keep an open mind in order to respond to new forms of diversity and new opportunities for collaborating with colleagues. Although continued professional development is necessary and important for teachers, it is a complex process. We refer to the work of Merchie et al. (2016) who identified nine characteristics of effective professional development, with one of them being that the supervisor is of high quality and is competent when it comes to giving and receiving constructive feedback and imparting other coaching skills (Merchie et al., 2016). Literature states that professional development is only successful if teachers are active participants, if they have a voice in what and how they learn things, and if the PDP is tailored to the specific context (Merchie et al., 2016). However, PDP often works towards a specific goal which is not always very flexible. A suitable coach is able to find a balance between these two extremes. Or, specifically within inquiry-based learning as an example, the coach needs to find the fragile balance between telling the teachers what to do, and letting them find their own answers. Finding such a balance and guiding teachers towards looking for and finding the answers they need is important if we wish to establish the desired improvement we want to see in teachers’ professional development. In this regard, Willegems et al. (2016) plead for the role of a broker as a bridge-maker in professional development trajectories, in addition to the role of coach (Willegems et al., 2016).

4.3 Importance of Collaboration

In addition, collaboration is indeed essential for effective professionalisation (Merchie et al., 2016) and beneficial for DI implementation (De Neve et al., 2015; Latz & Adams, 2011). In a professional development study where inquiry-based learning was applied to teams of teachers at schools, teachers reported positive experiences in discussing their individual learning activities, and during the programme became aware of the need to work together on the collective development of knowledge in the school. They all agreed that to implement DI they needed to collaborate more. A common school vision and policy is necessary for the implementation of specific differentiated measures, as these currently differ between teachers and grades, and can be confusing for students. This is consistent with previous research that states that collaboration is crucial for creating inclusive classrooms (Hunt et al., 2002; Mortier et al., 2010; EADSNE, 2012; Claasen et al., 2009; Mitchel, 2014). A first step in this process is realising that collaboration is beneficial for both teachers and students (EADSNE, 2012).

5 Conclusion

The chapter summarizes a doctoral dissertation that started with the assumption from theory that differentiated instruction can be adopted to create more inclusive classrooms. Theories describe DI as both a teaching practice and a philosophy, but the concept is rarely measured as such. Empirical evidence about the effectiveness and operationalisation of differentiating is limited. The general aim of this research was to gain a more in-depth understanding of the concept of DI. This main aim was subdivided into two objectives. The first objective focused on how DI is perceived by teachers and resulted in the DI-Quest model. The second objective focused on how DI is implemented. Four empirical studies were conducted to address these objectives. Two different samples spread over three years were adopted (1302 teachers in study 1 and 1522 teachers in studies 2, 3 and 4) and mixed methods were applied to investigate these research goals. In this chapter the results of these studies were put next to other studies and literature about differentiation. The conclusions highlight the importance of teachers’ philosophy when it comes to implementing DI, the importance of perceiving and implementing DI as a pedagogical model and the importance and complexity of professional development with regard to DI. Overall, the authors of this dissertation conclude that DI can be as promising as theories say when it comes to creating inclusive classrooms, but at the same time their research illustrated that the reality of DI in classrooms, is far more complex than the theories suggest.

References

Bade, J., & Bult, H. (1981). De praktijk van interne differentiatie. Handboek voor de leraar. Uitgeverij Intro Nijkerk.

Bearne, E. (2006). Differentiation and diversity in the primary school. Routledge.

Beecher, M., & Sweeny, S. M. (2008). Closing the achievement gap with curriculum enrichment and differentiation: One school’s story. Journal of Advanced Academica, 19(3), 502–530.

Claasen, W., de Bruïne, E., Schuman, H., Siemons, H. & van Velthooven, B. (2009). Inclusief bekwaam. Generiek competentieprofiel inclusief onderwijs - LEOZ Deelproject 4. Garant.

Brighton, C. M., Hertberg, H. L., Moon, T. R., Tomlinson, C. A., & Callahan, C. M. (2005). The feasibility of high-end learning in a diverse middle school. National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Coubergs, C., Struyven, K., Engels, N., Cools, W., & De Martelaer, K. (2013). Binnenklasdifferentiatie. Leerkansen voor alle leerlingen. Acco.

Coubergs, C., Struyven, K., Vanthournout, G., & Engels, N. (2017). Measuring teachers’ perceptions about differentiated instruction: The DI-Quest instrument and model. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 41–54.

De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 30–41.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

EADSNE (European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education). (2012). Lerarenopleiding en inclusie. Profiel van inclusieve leraren. European Agency for Development in Special Needs Education.

Endal, G., Padmadewi, N., & Ratminingsih, M. (2013). The effect of differentiated instruction and achievement motivation on students’ writing competency. Journal Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris, 1.

Gheyssens, E. (2020). Adopting differentiated instruction to create inclusive classrooms. Crazy Copy Center Productions.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Vanslambrouck, S., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020a). Differentiated instruction in practice: Do teachers walk the talk? Pedagogische Studieën, 97, 163–186.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020b). Good things come to those who wait: The importance of professional development for the implementation of differentiated instruction. Frontiers in Education, 5, 96.

Gheyssens, E., Coubergs, C., Griful-Freixenet, J., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2020c). Differentiated instruction: The diversity of teachers’ philosophy and practice to adapt teaching to students’ interests, readiness and learning profiles. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26, 1383.

Gheyssens, E., Consuegra, E., Engels, N., & Struyven, K. (2021). Creating inclusive classrooms in primary and secondary schools: From noticing to differentiated practices. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100, 103210.

Gijbels, D., Dochy, F., Van den Bossche, P., & Segers, M. (2005). Effects of problem-based learning: A meta-analysis from the angle of assessment. Review of Educational Research, 75(1), 27–61.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Taylor & Francis Ltd.

Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Müller, E., & Goetz, L. (2002). Collaborative teaming to support students with augmentative and alternative communication needs in general education classrooms. AAC: Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(1), 20–35.

Keay, J. K., & Lloyd, C. M. (2011). Developing inclusive approaches to learning and teaching. In J. K. Keay & C. M. Lloyd (Eds.), Linking children’s learning with professional learning. Impact, evidence and inclusive practice (pp. 31–44). Sense Publishers.

Latz, A. O., & Adams, C. M. (2011). Critical differentiation and the twice oppressed: Social class and giftedness. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 34(5), 773–789.

Mastropieri, M. A., Scruggs, T. E., Norland, J. J., Berkeley, S., McDuffie, K., Tornquist, E. H., & Connors, N. (2006). Differentiated curriculum enhancement in inclusive middle school science effects on classroom and high-stakes tests. The Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 130–137.

Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2016). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33, 1–26.

Mitchel, D. (2014). What really works in special and inclusive education. Using evidence-based teaching strategies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Mortier, K., Van Hove, G., & De Schauwer, E. (2010). Supports for children with disabilities in regular education classrooms: An account of different perspectives in Flanders. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(6), 543–561.

Op ‘t Eynde. (2004). Leren doe je nooit alleen: differentiatie als een sociaal gebeuren. Impuls, 35(1), 4–13.

Reis, S. M., McCoach, D. B., Little, C. A., Muller, L. M., & Kaniskan, R. B. (2011). The effects of differentiated instruction and enrichment pedagogy on reading achievement in five elementary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 462–501.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and Well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68.

Smale-Jacobse, A. E., Meijer, A., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Maulana, R. (2019). Differentiated instruction in secondary education: A systematic review of research evidence. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2366.

Sousa, D. A., & Tomlinson, C. A. (2011). Differentiation and the brain: How neuroscience supports the learner – Friendly classroom. Solution Tree Press.

Tobin, R. (2006). Five ways to facilitate the teacher assistant’s work in the classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 2(6), n6.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom. Responding to the needs of all learners. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2001). How to differentiate instruction in mixed-ability classrooms. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2005). Grading and differentiation: Paradox or good practice? Theory Into Practice, 44(3), 262–269.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2017). How to differentiate instruction in academically diverse classrooms. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2010). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. ASCD.

Tomlinson, C. A., Brighton, C., Hertberg, H., Callahan, C. M., Moon, T. R., Brimijoin, K., Conover, L. A., & Reynolds, T. (2003). Differentiating instruction in response to student readiness, interest and learning profile in academically diverse classrooms: A review of the literature. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 27(2/3), 119–145.

Valiandes, S. (2015). Evaluating the impact of differentiated instruction on literacy and reading in mixed ability classrooms: Quality and equity dimensions of education effectiveness. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45, 17–26.

van Kraayenoord, C. E. (2007). School and classroom practices in inclusive education in Australia. Childhood Education, 83(6), 390–394.

Vanderhoeven, J. L. (2004). Positief omgaan met verschillen in de leeromgeving. Een visie op differentiatie en gelijke kansen in authentieke middenscholen. Uitgeverij Antwerpen.

Whitburn, J. (2001). Effective classroom organisation in primary schools: Mathematics. Oxford Review of Education, 27(3), 411–428.

Willegems, V., Consuegra, E., Struyven, K., & Engels, N. (2016). How to become a broker: The role of teacher educators in developing collaborative teacher research teams. Educational Research and Evaluation, 22(3–4), 173–193.

Woolfolk, A. (2010). Educational psychology. The Ohio State University: Pearson Education International.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gheyssens, E., Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K. (2023). Differentiated Instruction as an Approach to Establish Effective Teaching in Inclusive Classrooms. In: Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Klassen, R.M. (eds) Effective Teaching Around the World . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31678-4_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-31677-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-31678-4

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)