Abstract

Integrity management in the context of the military relates to due care, to doing justice and decency and to reliability with respect to both soldiers and civilians. This contribution outlines the pillars of the integrity management system of the Netherlands armed forces, in which integrity management is approached as a three-layered framework of individual competencies, ethical climate and organisational design. Integrity management based on these three layers promotes that decisions are made professionally, prudently and in such a way as to do justice to all parties involved. This Dutch approach is not put forward as a one-size-fits-all solution, but as a discussion starter within the field of military ethics on how integrity management can be carried out in environments that are highly demanding.

The authors of this article were both employed with the Netherlands Defence Centre of Expertise for Integrity (COID); Claire Zalm until 2018, Miriam de Graaff until 2019. Claire Zalm is currently employed as the Director of Security, Crisis Management and Integrity at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Miriam de Graaff is currently employed as Head of the Joint Centre of Expertise for Communication and Engagement within the Royal Netherlands Army. The authors wrote this contribution in a private capacity and the viewpoints expressed do not necessarily reflect the position and/or policy of the Netherlands Ministry of Defence. The authors would like to express their gratitude to Tine Molendijk Ph.D. and Professor Dr. Eric-Hans Kramer for their feedback on previous drafts of this chapter.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

A commercial party invites a commanding officer for an exclusive dinner in a gourmet restaurant: the tender has been awarded. Is it wise to accept the offer? A military instructor is found to be rather intimidating and imposes higher demands on cadets than is required in the curriculum. Is this acceptable Bildung?

The above described situations are examples of daily ethical issues that are hardly ever considered ethical issues or dilemmas and fail to receive much attention in military ethics training. However, just like the more tragic ethical dilemmas such as, ‘whether to shoot or not’, they are not as easy to answer as might seem at first glance. At a personal level, individuals may be tempted to act in a certain way, regretting their choices afterwards. Or, they may feel confused about the right thing to do. Such daily dilemmas are at the centre of ethics management in the Dutch military: integrity management, which pertains to the professional performance of duties. Integrity management in the context of the military relates to due care, to doing justice and decency and to reliability with respect to the citizens of the Netherlands, the countries in which the Netherlands Defence organisation is active, and also with respect to its own personnel by providing them protection within the framework of an employer's responsibility. In this contribution, we outline the pillars of the integrity management system of the Netherlands armed forces. The purpose of this contribution is to provide some background on integrity management for public managers who currently work in a high-stakes environment such as the military. It is not our intent to claim that the Dutch approach is a one-size-fits-all solution; but rather our purpose is to start a discussion within the field of military ethics on how integrity management can be carried out in environments that are highly demanding, using the Dutch military as an example.

Managing Ethics, or Integrity Management

Ethical transgressions have a large impact on an organisation’s output, financial position and its employees, for example when due to counterproductive work behaviour, fraud or administrative evil (Kolthoff, 2016). However, unethical behaviour can have enormous societal impact as well due to state crime and human rights violations (Kolthoff, 2016). This is especially true in organisations that operate in the public sector, as violations by these organisations can lead to environmental hazards, health risks and may affect the personal lives and wellbeing of all individuals and parties involved (Hoekstra & Heres, 2016; Kolthoff, 2016). The importance of integrity management therefore lies not only in the contribution to positive organisational outcomes, but also in preventing the negative effects that a lack of public integrity may result in. It is for that reason that integrity is considered the cornerstone of good governance in the public sector of the Netherlands (Hoekstra & Heres, 2016). This emphasis on ethics, integrity management and integrity policy should also be present in military practice (cf. De Graaff, Schut, et al., 2017).

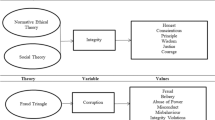

In academic literature, the terms integrity and ethics are often used interchangeably and as synonyms. However, in practice one often thinks of rule-following compliance when using the term integrity, whereas ethics often refers to a broader concept related to major moral choices, such as considerations as to whether or not participation in a war is to be considered just. In this chapter, we address the obligation of the military organisation to be a good employer to its employees and the positive pay off this has for all parties its personnel engages with. In many organisations, two types of management strategies aiming to promote morally responsible behaviour can be distinguished (Paine, 1994). The first is a rule-based and top down compliance approach, focusing on the prevention of misconduct and transgressions of laid down rules and procedures. The second is referred to as the integrity approach, which is value-based and bottom-up focusing on supporting individuals in making morally responsible decisions (Paine, 1994). Within the Netherlands armed forces, both approaches are recognised and both contribute to the organisation’s aim for good governance.

In this chapter, we consider integrity management to be a three-layered framework consisting of three distinct layers wherein both of the mentioned strategies can be implemented. These layers are individual competencies, ethical climate and organisational design; integrity management based on these three layers results in decisions being made professionally, prudently and in such a way as to do justice to all parties involved.

The individual level (layer one).

Activities in this layer concern stimulating the ability and the desire to make morally prudent choices, even if relevant legislation is unclear, lacking or not applicable. This individual agency perspective is also introduced and further deepened by Desiree Verweij as individual moral competenceFootnote 1 (Verweij, 2007) and is in line with Richardson, Verweij and Winslow’s perspective of moral fitness (2004). In most cases, stimulating individual morally responsible behaviour starts in a classroom or group training. This type of didactics works both ways in establishing individual competence through moral reflection as well as in mores or group culture (Van Baarle et al., 2015). Mores entail the second layer in integrity management. Individual awareness of the moral dimensions of any situation is activated when others share their dilemmas and ideas on how to solve an issue (Van Baarle et al., 2015). Also, being in a training setting together stimulates the onset of discourse, meaning in these settings all participants are forced to verbalise their moral intuitions and emotions. As such, group exercises and individual moral reflection helps in communicating about moral issues (Van Baarle et al., 2015).

However, the effectiveness of these ethics programmes in organisations is not always easy (or even possible) to identify. It is often also subject to debate. For example, Wang and Calvano (2015) showed that gender differences influence the effectiveness of certain aspects of ethics programmes. Weaver (2001) argues that the effectiveness of these ethics programmes may well be culturally undermined. On the other hand, in the Dutch military the results of ethics programmes for military instructors seem promising (Van Baarle et al., 2017), as do the results of Canadian battlefield ethics training (Thompson & Jetly, 2014).

Group level/ethical climate (layer two).

The second layer addresses the way people interact with one another. Examples of this second layer include informal standards and mores about employee voice and esprit de corps. A relevant aspect of team culture in this respect is the influence of role models and beliefs about what virtues the organisation or team stand for. In military training, a great deal of focus lies on the transfer of an esprit de corps in terms of shared virtues such as loyalty and obedience. However, the traditional military virtues that lie within this esprit de corps lead to a strong focus on one’s own group, disregarding other parties involved and other perspectives in the situation at hand (Verweij, 2013), which may in turn result in ethical failure by social psychological mechanisms such as groupthink (cf. De Graaff, De Vries, et al., 2017). It is therefore relevant to educate servicemen and women in recognising these mechanisms and their negative effects.

Both during military operations and during general peacetime operations, incidents that cannot pass muster do take place. Commanders are responsible for properly responding to any reports submitted by anyone in their chain of command. The core principle of the Dutch integrity policy is that members of staff call each other to account in the case of unacceptable behaviour. The main focus is on doing this timely and respectfully in order to prevent situations and behaviour from escalating. This is referred to as employee voice. A study conducted in the Netherlands armed forces on prosocial voice (i.e. attempting to improve the situation by addressing the behaviour of co-workers by expressing one’s own opinions and feelings) showed that when individuals consider it to be normal in their working environment to speak up and confront co-workers, they are more inclined to do so regardless of the behaviours of others and what they actually see that others are doing in terms of voice (Hilverda et al., 2018).

The structural/design level (layer three).

The third layer is made up of the role played by the organisation to encourage and facilitate its personnel to perform their work in a morally prudent fashion. This concerns the formal structure of the organisation and involves the organisation being aware of the vulnerable position of its personnel, of high-risk processes and of legislative developments (De Graaff, Schut, et al., 2017; De Graaff & Van den Berg, 2010).

Some years ago, a risk analysis was performed on the Dutch officers’ training programme (Governance and Integrity, 2013). One of the conclusions of this analysis was that the final assessment of cadets could be made more objective and would benefit from further standardisation, so as to guarantee a more equal treatment. This resulted in a multi-disciplinary project being launched to further professionalise the training process. The project team worked on, inter alia, making the instructors aware of their crucial and, at the same time, vulnerable position in the training process, on embedding integrity into the instructors’ training courses, on evaluating the cadet assessment process and on reformulating the course requirements. The cadets and their instructors themselves were also involved in the project. At the same time, stock was taken of the way ethics and integrity were taught in the various career training programmes and to what extent this was in line with the duties cadets are expected to perform upon finishing the programme concerned.

Doing justice to all parties involved is the core principle of the integrity policy of the Netherlands Defence organisation (Secretary-General, no date). This is formulated as follows: To treat each other and others with respect, taking account of the rights, interests and wishes of all parties involved. This does not mean that everyone will always be happy with the choices that are made. What it does mean is that all choices can be explained and that a decision is not based on a single point of view. Such also becomes apparent from the reference made in the organisation’s integrity policy to the term respect. The Latin verb respectare has multiple meanings, including looking after others. In other words, when acting from this perspective, whenever there is interaction with others, the MOD wants to look after and make allowances for the persons involved. In the Dutch Defence Code of Conduct, this policy has been translated into cornerstones that are relevant to all employees and that in the main relate to manners and conduct. The (value driven) cornerstones are: commitment (in Dutch: verbondenheid), safety (in Dutch: veiligheid), trustworthiness (in Dutch: vertrouwen) and responsibility (in Dutch: verantwoordelijkheid) (Ministry of Defence, 2018).

Institutionalising Integrity Management in the Dutch Military

The Netherlands armed forces organise both preventive activities and activities based on violations that may be expected due certain vulnerabilities and risks in the working procedures and parties involved. Within the armed forces, several departments cooperate in initiatives providing support to the Defence organisation and its staff by performing preventive activities in all three of the described layers. For example, they cooperate at strengthening moral competence by providing so-called dilemma training sessions (layer one), providing insight into the level of the ethical climate within a unit by conducting research into the culture (layer two), and charting vulnerable organisational structures and working processes by performing risk analyses (layer three). Departments that play a role in these prevention activities are, inter alia, the Defence Centre of Expertise for Integrity (COID),Footnote 2 the School for Peace Operations (SVV) and the Defence Centre of Expertise for Leadership Development (ECLD).

Scientific research has shown that Dutch military personnel face various dilemmas during military operations, for instance in the context of experiencing cultural differences (cf. De Graaff et al., 2016; Schut & Moelker, 2015). In many countries, ethics training is carried out in relation to military operations and deployment, such as Canada (Warner et al., 2011), the Netherlands (De Graaff, Schut, et al., 2017), Switzerland and the United States (Williams, 2010). In the Netherlands, for instance, it is customary to prepare ship’s crews, prior to a long-term posting at sea, for confrontations with possible temptations and possible ethical dilemmas; temptations that come with the posting and run counter to organisational rules and standards. Examples are having to deal with seized contraband such as drugs; ribbing that turns to bullying due to being cooped up in close quarters for a prolonged period of time; or cultural differences resulting in undesirable behaviour. However, when it comes to the daily issues as described in the introduction, only a few programmes focus on this aspect of integrity management. We argue that these efforts should be intensified. Such educational and training activities may not only result in positive organisational results (i.e. fewer incidents and scandals), but may also have a positive effect on employee well-being (Thompson & Jetly, 2014) by acknowledging how an individual is influenced by these situations in terms of moral emotions (De Graaff et al., 2016; Schut et al., 2015) and maybe even moral injury (Molendijk, 2018).

When situations do not only cross the line of what employees individually consider to be acceptable behaviour, but violate organisational boundaries as well (e.g. misconduct and fraud), employees ought to report such behaviour to their commander, who will take further action. In (potentially) harmful and complex cases, employees have the possibility of whistleblowing, meaning they consult a third party before stakeholders are involved in resolving the complaint. Should the employee not or not yet be sure of which action to take, they may contact a confidential advisor (in Dutch: Vertrouwenspersoon). Such advisors provide emotional support, are familiar with the procedures and are able to suggest alternative, informal solutions. The Netherlands Defence organisation includes a network of about 600 confidential advisors who perform their advisory work in an ancillary position. In addition, all personnel may consult and discuss personal dilemmas with Military Chaplaincy personnel. This is a network of officials contributing to the (spiritual) welfare of military personnel and other Defence staff and to the morality of the armed forces as a whole from a Jewish, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Humanist, Hindu or Islamic tradition, education and background.

The Netherlands armed forces also have a long tradition of the so-called ‘Non-Commissioned Officers Chain’, the senior non-commissioned officer serving as an assistant to the commander in case of incidents. Because of the role and position, the senior non-commissioned officer is the obvious person in the chain of command to call attention to problems and think of solutions. This role and position also allows the non-commissioned officer serving as assistant to the commander to broach issues at the right level, mediate where necessary or settle a case with a customised solution on behalf of the commander.

In addition to reporting an incident up the chain of command, staff may also report to the Integrity Reporting Office (in Dutch: Meldpunt) if they feel they are not heard by their commanding officers for any reason, or are afraid to report to them. For commanding officers themselves, the previously mentioned COID is an internal department that focuses on providing support to those commanding officers in dealing with suspected violations meticulously; this entails, for instance, rendering advice on how to deal with reports and what to communicate, on the suitability of conducting an investigation, and, when necessary, on providing investigators. Should an investigation be initiated, the legal department and HR also often play a part.

At times, personnel are unable to resolve their problems within the organisation and with the support of the existing systems. In such cases, they may contact the Inspector-General of the Armed Forces (Inspecteur-Generaal Krijgsmacht, IGK), an official who acts outside of the formal organisational structure of the Ministry and who directly reports to the Minister of Defence. Each individual military or civilian member of staff or their family may contact the IGK. The IGK listens to their concerns and tries to bring the parties together to work on a solution, if necessary. Obviously, next to the possibility of consulting the IGK, the previously mentioned office for whistleblowing is a possibility at hand.

Conclusion

To summarise, the Netherlands armed forces are equipped with a plethora of departments, officials and initiatives to increase moral fitness within the organisation. Yet despite all of these measures (drawn up in writing), ethics officials (from coaches, integrity advisors, analysts and instructors) ought to stay connected and keep their ‘boots on the ground’ in order for integrity management to be both practical and to be put into practice. Put into practice not only by these officials, but by all personnel. Doing so will ensure that integrity management is not reduced to mere window-dressing, but in fact receives the importance it deserves and is carried into effect by all.

We argue that for coming to a morally responsible solution in day-to-day ethical dilemmas as described in the introduction, similar activities are necessary in integrity management as for answering the broader ethical questions regarding just war principles or tragic dilemmas in, for example, encountering hostile non-combatants or child soldiers. Therefore, we believe integrity management and day-to-day (peacetime) ethical issues should be more integrated into military ethics training, discussions and considerations. Such issues ought not to be disregarded and neglected, as they may result in organisational problems, individual issues and negative emotions in the long term.

Notes

- 1.

Moral competence comprises six elements (based on Verweij, 2007):

-

(a)

Moral awareness—recognising the moral dimension of a situation.

-

(b)

Self-reflection—being aware of one's personal standards and values and possible bias about a situation.

-

(c)

Moral understanding—being able to formulate various courses of action and their consequences.

-

(d)

Moral opinion forming—being able and willing to make a decision and act accordingly.

-

(e)

Responsibility and communication—being able and willing to communicate the reasons and considerations underlying a choice made to others. Taking responsibility.

-

(f)

Moral resilience—being able to cope with the tragic consequences of choices made.

-

(a)

- 2.

The COID is a centre of expertise that supports the Defence organisation to do justice to all parties involved and to do so in a respectful manner. It provides such support by, inter alia, providing advice, training courses and workshops, and by performing investigations and analyses, both preventatively and following suspected violations. The COID is internationally considered an example for other armed forces to follow, as is recognised in the 2016 van der Steenhoven report on integrity within the Netherlands Defence organisation (Van der Steenhoven & Aalbersberg, 2016).

References

De Graaff, M. C., De Vries, P. W., Van Bijlevelt, W. J., & Giebels, E. (2017). Ethical leadership in the military, the gap between theory and practice in ethics education. In P. J. Olsthoorn (Ed.), Ethics in military leadership (pp. 56–85). Brill.

De Graaff, M. C., Schut, M., Verweij, D. E. M., Vermetten, E., & Giebels, E. (2016). Emotional reactions and moral judgment: The effects of morally challenging interactions in military operations. Ethics & Behavior, 26(1), 14–31.

De Graaff, M. C., Schut, M., & Zalm, C. E. (2017). Morele fitheid in militaire inzet, de noodzaak van aandacht voor integriteit ook in het ‘echte’ werk. In N. Boonstra, et al. (Eds.), Jaarboek Compliance 2017. Nederlands Compliance Instituut.

De Graaff, M. C., & Van den Berg, C. E. M. (2010). Moral professionalism within the Royal Netherlands Armed Forces. In J. Stouffer & S. Seiler (Eds.), Military ethics, international perspectives (pp. 1–24). Canadian Defence Academy Press.

Governance & Integrity. (2013). Integriteit bij de opleiding en vorming van adelborsten en cadetten aan de Nederlandse Defensie Academie. Duiding van risico’s, perspectief of verbetering. Ministerie van Defensie.

Hilverda, F., van Gils, R., & De Graaff, M. C. (2018). Confronting co-workers: Role models, attitudes, expectations, and perceived behavioral control as predictors of employee voice in the military. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2515.

Hoekstra, A., & Heres, L. (2016). Ethical probity in the public service. In A. Farazmand (Eds.), Global encyclopedia of public administration, public Policy and governance. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_922-1

Kolthoff, E. (2016). Integrity violations, white-collar crime, and violations of human rights: Revealing the connection. Public Integrity, 18(4), 396–418.

Ministerie van Defensie. (2018). Gedragscode. Ministerie van Defensie. Retrieved online: April 16, 2022. https://www.defensie.nl/downloads/publicaties/2018/12/04/gedragscode-defensie

Molendijk, T. (2018). Toward an interdisciplinary conceptualization of moral injury: From unequivocal guilt and anger to moral conflict and disorientation. New Ideas in Psychology, 51, 1–8.

Paine, L. S. (1994). Managing for organizational integrity. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 106–117.

Richardson, R., Verweij, D., & Winslow, D. (2004). Moral fitness for peace operations. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 32(1), 99–113.

Schut, M., De Graaff, M. C., & Verweij, D. (2015). Moral emotions during military deployments of Dutch forces: A qualitative study on moral emotions in intercultural interactions. Armed Forces & Society, 41(4), 616–638.

Schut, M., & Moelker, R. (2015). Respectful agents: Between the Scylla and Charybdis of cultural and moral incapacity. Journal of Military Ethics, 14, 232–246.

Secretary General. (no date). Instruction of the Secretary General 984—Implementation of the Integrity Policy. Ministerie van Defensie.

Thompson, M. M., & Jetly, R. (2014). Battlefield ethics training: Integrating ethical scenarios in high-intensity military field exercises. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 23668.

Van Baarle, E., Bosch, J., Widdershoven, G., Verweij, D., & Molewijk, B. (2015). Moral dilemmas in a military context: A case study of a train the trainer course on military ethics. Journal of Moral Education, 44(4), 457–478.

Van Baarle, E., Hartman, L., Verweij, D., Molewijk, B., & Widdershoven, G. (2017). What sticks? The evaluation of a train-the-trainer course in military ethics and its perceived outcomes. Journal of Military Ethics, 16(1–2), 56–77.

Van der Steenhoven, K., & Aalbersberg, M. (2016). Moral Fitness, een onderzoek naar de integriteit van de defensieorganisatie ten aanzien van de omgang met commerciële partijen op het gebied van IT. ABD TOP Consult.

Verweij, D. E. M. (2007). Morele professionaliteit in de militaire praktijk. In J. Kole & D. De Ruyter (Eds.), Werkzame Idealen, ethische reflecties op professionaliteit (pp. 126–138). Koninklijke van Gorcum.

Verweij, D. E. M. (2013). Responsibility as the ‘ability to respond’ adequately? In H. Amersfoort, R. Moelker, & J. Soeters (Eds.), Moral responsibility & military effectiveness (pp. 11–32). T.M.C. Asser Press.

Wang, L. C., & Calvano, L. (2015). Is business ethics education effective? An analysis of gender, personal ethical perspectives, and moral judgment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126(4), 591–602.

Warner, C. H., Appenzeller, G. N., Mobbs, A., Parker, J. R., Warner, C. M., Grieger, T., & Hoge, C. W. (2011). Effectiveness of battlefield-ethics training during combat deployment: A programme assessment. The Lancet, 378(9794), 915–924.

Weaver, G. R. (2001). Ethics programs in global businesses: Culture’s role in managing ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(1), 3–15.

Williams, K. R. (2010). An assessment of moral and character education in initial entry training (IET). Journal of Military Ethics, 9(1), 41–56.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

de Graaff, M.C., Zalm, C. (2023). The Dutch Approach to Ethics: Integrity Management in the Military. In: Kramer, EH., Molendijk, T. (eds) Violence in Extreme Conditions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16119-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-16119-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-16118-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-16119-3

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)