Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy with BCMA-directed autologous CAR-T cells has shown very encouraging results in end-stage relapse and refractory multiple myeloma (MM), with overall response rates ranging between 73% and 96.9%, complete response (CR) rates between 33% and 67.9%, and MRD negativity in 50–74% of patients in the two largest phase 2 studies of ide-cel (idecabtagene autoleucel, KarMMa) and cilta-cel (ciltacabtagene autoleucel, CARTITUDE 1) reported thus far (Madduri et al. 2020; Munshi et al. 2021). Unfortunately, responses are usually not maintained, and no plateau has yet been seen in the survival curves. The median progression-free survival (PFS) in the KarMMa study of ide-cel was 8.8 months (95% CI, 5.6–11.6) among all 128 patients infused, increased to 12.1 months (95% CI, 8.8–12.3) among patients receiving the highest dose (450 × 106 CAR + T cells) and increased to 20.2 months (95% CI, 12.3–NE) among those achieving a CR. In the CARTITUDE-1 study, with a median follow-up of 12.4 months, the median PFS has not yet been reached, and the 12-month PFS rate was 76.6% (95% CI; 66.0–84.3). The absence of a clear plateau in PFS differs from what has been observed in DLBCL or B-ALL with currently approved CD-19-directed CAR-T cells, where (albeit with a shorter PFS and lower rates of CR) patients remaining free from relapse beyond 6 months are likely to enjoy prolonged disease control or even be cured.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoptive cell therapy with BCMA-directed autologous CAR-T cells has shown very encouraging results in end-stage relapse and refractory multiple myeloma (MM), with overall response rates ranging between 73% and 96.9%, complete response (CR) rates between 33% and 67.9%, and MRD negativity in 50–74% of patients in the two largest phase 2 studies of ide-cel (idecabtagene autoleucel, KarMMa) and cilta-cel (ciltacabtagene autoleucel, CARTITUDE 1) reported thus far (Madduri et al. 2020; Munshi et al. 2021). Unfortunately, responses are usually not maintained, and no plateau has yet been seen in the survival curves. The median progression-free survival (PFS) in the KarMMa study of ide-cel was 8.8 months (95% CI, 5.6–11.6) among all 128 patients infused, increased to 12.1 months (95% CI, 8.8–12.3) among patients receiving the highest dose (450 × 106 CAR + T cells) and increased to 20.2 months (95% CI, 12.3–NE) among those achieving a CR. In the CARTITUDE-1 study, with a median follow-up of 12.4 months, the median PFS has not yet been reached, and the 12-month PFS rate was 76.6% (95% CI; 66.0–84.3). The absence of a clear plateau in PFS differs from what has been observed in DLBCL or B-ALL with currently approved CD-19-directed CAR-T cells, where (albeit with a shorter PFS and lower rates of CR) patients remaining free from relapse beyond 6 months are likely to enjoy prolonged disease control or even be cured.

Mechanisms of resistance and relapse following CAR-T cell therapy in MM are poorly understood, and several factors may explain these differences in survival (D’Agostino and Raje 2020; Rodríguez-Otero et al. 2020). MM is a very heterogeneous disease with important clonal heterogeneity and a highly deregulated marrow microenvironment. In addition, CAR-T cell therapy has been evaluated in very heavily pretreated populations, with a significant proportion of patients being triple-class refractory and exposed to all available therapies, reflecting a difficult-to-treat population with an expected PFS of less than 4 months (Gandhi et al. 2019).

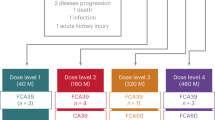

To maintain responses and prolong survival, different strategies are being investigated, such as dual targeting to prevent antigen loss (Jiang et al. 2020) and manufacturing changes to increase the proportion of long-lived T cells with a memory phenotype in the infused product, which has been associated with improved outcomes and longer CAR-T cell persistence (Alsina et al. 2020; Costello et al. 2019; Fraietta et al. 2018). The most advanced strategy to consolidate responses is combination with immunostimulatory drugs, such as IMIDs or checkpoint inhibitors, to improve functional CAR-T cell persistence and avoid exhaustion. Several clinical trials using these strategies are ongoing.

Interestingly, considering relapse after CAR-T cell therapy, emerging data show a discordance between PFS and overall survival (OS). In the updated results from the CRB-401 phase 1 study, the median PFS and OS reported were 8.8 (95% CI 5.9–11.9) and 34.2 (95% CI, 19.2–NE) months, respectively, across all doses (Lin et al. 2020). OS data in the KarMMa study are still immature, with 66% of patients censored overall (Munshi et al. 2021). Thus far, this gap between PFS and OS is not as clear in other studies, but the follow-up time is still very short for the majority of the trials. In the Legend-2 study, one of the BCMA studies with a longer follow-up time, the median PFS for all treated patients was 20 months, and the median OS was not reached, with an 18-month OS rate of 68% (Chen et al. 2019). This suggests that MM patients relapsing after CAR-T cell therapy may subsequently respond to salvage treatments, including drug combinations that have previously failed. One can speculate about potential modifications of the immune system or the bone marrow microenvironment induced by CAR-T cells. Unfortunately, data addressing this phenomenon are not yet available. Furthermore, CAR-T cell therapy has been shown to significantly improve health-related quality of life (Cohen et al. 2020; Martin III et al. 2020; Shah et al. 2020), and this better physical condition together with a prolonged treatment-free interval are two key factors that may predispose patients to accept additional rescue therapies, which would also contribute to the OS gain.

Unfortunately, data are not yet available to elucidate what optimal rescue therapies should be proposed after CAR-T cell progression. Anecdotal cases of patients progressing after BCMA-directed CAR-T cell infusion and then treated with other BCMA agents, such as belantamab mafodotin or checkpoint inhibitors, have been reported and showed that this approach has limited efficacy (Cohen et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the optimal approach in patients failing BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy will be to employ therapies with different mechanisms of action (Melflufen, CELMODs, Selinexor) or immunotherapies directed against different targets, such as SLAMF7, GPRC5D or FcRH5, using either bispecific T-cell engagers (Talquetamab or Cevostamab) or even CAR-T cells. Indeed, new treatment modalities and data from early phase studies including patients relapsing after CAR-T cell therapy will provide the answer to this challenging problem: “Relapse following BCMA CAR-T cell therapy: hope for further life.”

-

BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy shows very encouraging results in triple-class refractory multiple myeloma populations, but there is not yet a survival plateau.

-

In the CRB-401 study, an important gap between PFS (median PFS of 8.8 months) and OS (median OS of 34.2 months) was observed, suggesting that patients failing BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy may subsequently respond to salvage treatments.

-

Data are not yet available to elucidate what optimal rescue therapies should be proposed after CAR-T cell progression.

-

Salvage treatments after CAR-T cell treatment should include drugs with new mechanisms of action (i.e., Melflufen, Selinexor, CelMods) or targeting different antigens on the surface of plasma cells (i.e., GPRC5dD (talquetamab) or FcRH5 (cevostamab).

References

Alsina M, Shah N, Raje NS, et al. Updated results from the phase I CRB-402 study of anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy bb21217 in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: correlation of expansion and duration of response with T cell phenotypes. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):25–6. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-140410.

Chen L, Xu J, Fu W Sr, et al. Updated phase 1 results of a first-in-human open-label study of Lcar-B38M, a structurally differentiated chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). Blood. 2019;134(Suppl_1):1858. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-130008.

Cohen AD, Garfall AL, Dogan A, et al. Serial treatment of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma with different BCMA-targeting therapies. Blood Adv. 2019;3(16):2487–90. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000466.

Cohen AD, Hari P, Htut M, et al. Patient expectations and perceptions of treatment in CARTITUDE-1: phase 1b/2 study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):13–5. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136383.

Costello CL, Gregory TK, Ali SA, et al. Phase 2 study of the response and safety of P-BCMA-101 CAR-T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory (r/r) multiple myeloma (MM) (PRIME). Blood. 2019;134(Suppl_1):3184. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2019-129562.

D’Agostino M, Raje N. Anti-BCMA CAR-T cell therapy in multiple myeloma: can we do better? Leukemia. 2020;34(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0669-4.

Fraietta JA, Lacey SF, Orlando EJ, et al. Determinants of response and resistance to CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Med. 2018;24(5):563–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0010-1.

Gandhi UH, Cornell RF, Lakshman A, et al. Outcomes of patients with multiple myeloma refractory to CD38-targeted monoclonal antibody therapy. Leukemia. 2019;33(9):2266–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0435-7.

Jiang H, Dong B, Gao L, et al. Clinical results of a multicenter study of the first-in-human dual BCMA and cd19 targeted novel platform fast CAR-T cell therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):25–6. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-138614.

Lin Y, Raje NS, Berdeja JG, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel, bb2121), a BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy, in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: updated results from Phase 1 CRB-401 study. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):26–7. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-134324.

Madduri D, Berdeja JG, Usmani SZ, et al. CARTITUDE-1: phase 1b/2 study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy, in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):22–5. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136307.

Martin T III, Lin Y, Agha M, et al. Health-related quality of life in the cartitude-1 study of ciltacabtagene autoleucel for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):41–2. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136368.

Munshi NC, Anderson LDJ, Shah N, et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):705–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2024850.

Rodríguez-Otero P, Prósper F, Alfonso A, et al. CAR-T cells in multiple myeloma are ready for prime time. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11) https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9113577.

Shah N, Delforge M, San-Miguel JF, et al. Secondary quality-of-life domains in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma treated with the BCMA-directed CAR-T cell therapy idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel; bb2121): results from the Karmma clinical trial. Blood. 2020;136(Suppl 1):28–9. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2020-136665.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rodríguez-Otero, P., San Miguel, J.F. (2022). Post-CAR-T Cell Therapy (Consolidation and Relapse): Multiple Myeloma. In: Kröger, N., Gribben, J., Chabannon, C., Yakoub-Agha, I., Einsele, H. (eds) The EBMT/EHA CAR-T Cell Handbook. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94353-0_34

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94353-0_34

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94352-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94353-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)