Abstract

Traditional monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) approaches, methods, and tools no longer reflect the dynamic complexity of the severe (or “super-wicked”) problems that define the Anthropocene: climate change, environmental degradation, and global pandemics. In late 2019, the Adaptation Fund’s Technical Evaluation Reference Group (AF-TERG) commissioned a study to identify and assess innovative MEL approaches, methods, and technologies to better support and enable climate change adaptation (CCA) and to inform the Fund’s own approach to MEL. This chapter presents key findings from the study, with seven recommendations to support a systems innovation approach to CCA:

-

1.

Promote and lead with a CCA systems innovation approach, engaging with key concepts of complex systems, super-wicked problems, the Anthropocene, and socioecological systems.

-

2.

Engage better with participation, inclusivity, and voice in MEL.

-

3.

Overcome risk aversion in CCA and CCA MEL through field testing new, innovative, and often more risky MEL approaches.

-

4.

Demonstrate and promote using MEL to support and integrate adaptive management.

-

5.

Work across socioecological systems and scales.

-

6.

Advance MEL approaches to better support systematic evidence and learning for scaling and replicability.

-

7.

Adapt or develop MEL approaches, methods, and tools tailored to CCA systems innovation.

Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.

Steve Jobs

What is now proved was once only imagined.

William Blake

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Adaptation Fund was established by the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP) of the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) to finance concrete adaptation projects and programs in developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. At the Katowice Climate Conference in December 2018, the Parties to the Paris Agreement (CMA) decided that the Adaptation Fund shall also serve the Paris Agreement.

In late 2019, the Adaptation Fund’s Technical Evaluation Reference Group (AF-TERG) commissioned a study to identify and assess innovative monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) approaches, methods and technologies to better support and enable climate change adaptation (CCA). The study aimed to contribute to new knowledge on innovative MEL opportunities to both support and enable CCA and contribute to and inform the fund’s own approach to MEL.

This chapter presents key findings from the study to a wider CCA MEL audience and concludes with a series of recommendations on future directions for MEL commissioners and practitioners working in the context of CCA and systems transformation.

Study Purpose and Approach

The study took a broad and open-ended approach to identifying innovative MEL for CCA, applying a scan-search-appraise method to look within and beyond the CCA sector to identify potentially innovative and useful MEL practices for CCA. The method is essentially a structured funneling and sieving process, refining from a broad field or landscape down to set of focused priorities or conclusions. The scan phase was a relatively rapid and high-level assessment of the whole innovative MEL field or landscape, comprising an open-ended online literature review and five open-ended key informant interviews. The search phase took the overview provided by the scan phase and refined it in the context of adaptation, using a more systematic document review process and 10 semistructured key informant interviews.

The purpose of the study was to identify innovative MEL practices within and beyond the climate adaptation space (scan and search) of potential value and use to the Adaptation Fund (appraise). The scope of the study was explicitly broad, to look beyond MEL methods, tools, and technologies to include wider and emerging MEL-relevant principles, approaches, and processes. The foundational concepts of innovation, adaptation, and MEL are defined as follows:

-

Innovation – There is no single definition of innovation. The study adopted a simple yet comprehensive definition of innovation that resonates with innovative MEL as a concept and can be applied to both technological and process innovation: “Innovation is the renewing, advancing, or changing the way things are done” (Everett et al., 2011, p. 6).

-

Adaptation – “The process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, adaptation seeks to moderate or avoid harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In some natural systems, human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects” (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2014, p. 1758).

-

Monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) – The emphasis of the definition in the context of the study was to break MEL down into its three separate but overlapping parts—monitoring, evaluation, and learning—as part of a virtuous project cycle informing project course correction, design, delivery, and learning in an ongoing process.

-

Monitoring – In the context of MEL, monitoring is a continuous assessment that aims at providing stakeholders with early, detailed information on the progress of an intervention. In the context of the Adaptation Fund, monitoring should support near to real-time learning as part of a wider approach to flexible and adaptive management.

-

Evaluation – Building on the definition from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Development Assistance Committee Working Party on Aid Evaluation, 2002), evaluation refers to the process of determining the worth or significance of an activity, policy, program, or institution—an assessment, as systematic and objective as possible, of a planned, ongoing, or completed development intervention. Useful and robust evaluation should inform both accountability and learning, depending on the emphasis of the evaluation questions.

-

Learning – In essence, learning is about understanding what works, in what contexts, for whom, and why. Learning should support direct and rapid course correction of an intervention and generate evidence and knowledge on the scalability and/or transferability of interventions across contexts. In the context of the Adaptation Fund, learning should be linked to the building of capacities, particularly adaptive capacity, of all stakeholders—beneficiaries, implementers, managers, and wider interest audiences. It should also reflect how these stakeholders learn through double and triple-loop learning processes.

-

The study’s scan-search-appraise methodology began from the following three-step hypothesis:

-

1.

Climate change is a “super-wicked problem,”Footnote 1 shaped by the complex and dynamic interactions of social, economic, and environmental factors that define the Anthropocene era.

-

2.

Successful CCA requires innovative and transformative ways of doing development, notably through a systems innovation approach.

-

3.

MEL theory and practice needs to adapt and evolve to better support a systems innovation approach in CCA.

Complexity, Systems Innovation, and CCA

Social innovation and innovation for development in the context of today’s global challenges are the focus of this section of the chapter. Innovation is increasingly seen as central to addressing the interlinked global challenges of poverty, inequality, and climate change. The latest thinking on social innovation and innovation for development is shaping how CCA is defined, understood, and addressed.

The concept of systems innovation is critical for successful CCA. In response to the finding that systems innovation approaches and business-as-usual MEL approaches are increasingly disconnected, we suggest that systems innovation and complexity offer the MEL community,Footnote 2 particularly those involved in CCA, an opportunity to evolve and advance MEL mindsets, approaches, and methods.

CCA, Complex Systems, and Innovation: Evolution to the Present Day

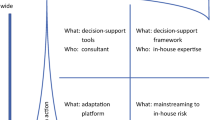

The Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium (TIPC) has produced a simple and elegant three-frame model (Fig. 1) that summarizes the major phases or frames of innovation theory and policy and places them in historical context. (Schot & Steinmueller, 2018; TIPC, 2018).

Frame 1 is identified as beginning with a post-World War II institutionalization of government support for science and research and development (R&D) with the presumption that this would contribute to growth and address market failure in private provision of new knowledge. Frame 1 builds on the thinking of some of the originators of innovation theory, notably Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950) and his thinking that innovation and technological change of a nation comes from the interaction between government, scientists (inventors), and industry actors. Frame 1 produces a simple linear model of innovation focused on enhancing national economic growth through the overcoming of market failures in science and technology research. It identifies the discovery process (invention) in which technology is the application of scientific knowledge as the most important element of innovation.

Frame 2 represents the evolution of innovation theory and policy up to the present day and incorporates the perspectives of influential innovation thinkers such as Mariana MazzucatoFootnote 3 and Daniel Kahneman,Footnote 4 among others. While still focusing on innovation to support economic growth (rather than wider social and environmental needs), this frame emphasizes a more complex and dynamic relationship between key innovation stakeholders—actors, networks, and institutions—and stresses feedback loops between invention, innovation, and use. Innovation theory and policy draw on and have been influenced by the fields of behavioral economics, positive psychology, and public policy. Under this frame, Mazzucato and others recently have emphasized the critical role of entrepreneurs, and the relationship between the state/national systems and entrepreneurial actors.

Frame 3 is emerging and focuses on mobilizing the power of innovation to address a wide range of societal challenges, including inequality, unemployment, and climate change. It calls on “social innovation” to provide transformative change in the face of “grand challenges” (Schot & Steinmueller, 2018) and super-wicked problems. It notes that these challenges and problems extend across multiple scales that transcend national, sectoral, technological, and disciplinary boundaries. Solving these global environmental and societal problems requires the engagement of a much broader set of actors. Innovation theory (and emerging policy) in this area combines long-established academic thought in the areas of new institutional economics, public policy, common pool resources, and socioecological systems—drawing on the work of political economists such as Elinor OstromFootnote 5—and combines this with new and emerging theory and practice in the areas of complex and adaptive systems, transformational change, and experimentation and active sensing. This third and latest frame of innovation builds on and embraces a small number of broader emerging concepts that relate to better conceptualizing and understanding the world. We present the key concepts in a short glossary, below.

-

The Anthropocene: The nature of humans’ impact on the global biophysical system has become so dominant that scientists have proposed that the last 216 years of the existing Holocene period should become recognized as a new geological epoch, termed the Anthropocene. The concept of the Anthropocene has been suggested as a new geological era marked by global threats and challenges, the greatest of these being climate change, which are defined by the dynamic interactions between human and environmental systems (Olsson et al., 2017).

-

Super-wicked problems: Climate change is the greatest single threat facing the planet, threatening both natural and human systems. Addressing this urgent and intensifying threat is a complex, dynamic, and frequently contested challenge. Recognition is increasing that super-wicked problems (Balint et al., 2011; Levin et al., 2012), such as climate change, global pandemics, and rising inequality, require a fundamentally different approach from previous eras in history. Levin et al. (2012) define super-wicked problems as having four core characteristics: (a) time is running out, (b) those who cause the problem also seek to provide a solution, (c) the central authority needed to address the issue is weak or nonexistent, and (d) irrational discounting occurs that pushes responses into the future.

-

Complex adaptive systems: The notion of complexity as the property of a system is not new. But more recently, researchers have advanced the concept of complex adaptive systems (CAS) as a way of better understanding the global challenges characterized by complex interactions between human and environmental systems. David Snowden’s Cynefin Framework (Snowden & Boone, 2007) was one of the first and is still the most elegant explanation of systems sense making. Framing climate change within a CAS has profound implications for how the challenge is understood and addressed (Preiser, 2018), and for how MEL of CCA is approached and delivered to support positive change.

-

Resilient and transformational change: Resilience is the capacity of a system to reorganize after a disruption (climatic shock or stress) without losing the essential functions of that system. The capacity for a social system (e.g., individuals, organizations, neighborhoods, communities, whole societies) to absorb disturbance and adapt where necessary, while undergoing significant change, is the defining characteristic of someone or something that is resilient. Although resilience is about maintaining the essential functions of a system, transformation is commonly interpreted as radical change requiring innovation and testing of new approaches. For climate change, this entails the generation of new knowledge and a markedly different way of doing things in order to address a threat of this scale (Climate Investment Funds, 2019). Both concepts—resilience and transformational change—have received heightened attention in response to the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased recognition of economic and social systems shifting from those based primarily on efficiency to those defined by economic, social, and environmental resilience.

The third frame of the TIPC model and the concepts above are united and integrated in the field of social innovation, which draws on a tradition of broader innovation theory and policy and refines the innovation concept in recognition of complex and systemic social and environmental problems such as poverty, climate change, unemployment, discrimination, and biodiversity loss. According to the Center for Social Innovation (2020):

Social innovation is the process of developing and deploying effective solutions to challenging and often systemic social and environmental issues in support of social progress. Social innovation is not the prerogative or privilege of any organizational form or legal structure. Solutions often require the active collaboration of constituents across government, business, and the non-profit world.

Frances Westley,Footnote 6 a global thought leader on social innovation, described social innovation as:

any initiative (product, process, program, project, or platform) that challenges and, over time, contributes to changing the defining routines, resource and authority flows, or beliefs of the broader social system in which it is introduced. Successful social innovations have durability, scale and transformative impact.Footnote 7

The concept of social innovation has several tenets that are particularly relevant to innovation for development and have profound implications for MEL. Resilient and transformational change is one of the tenets already mentioned as part of the third frame of innovation. Two other principles are:

-

Scales and their actors: Westley and others engaged in social innovation scaling talk in terms of three forms: (a) scaling out, which is based on market-based technological innovation scaling; (b) scaling-up, which involves scaling from individual social entrepreneurs to institutional and system entrepreneurs to take an innovation and find resources for it to reach a tipping point so that the institutional context of that innovation shifts to a new state (e.g., impact investing); and (c) scaling deep, which relates to deep, long-term, and profound shifts in culture, attitudes, and behaviors toward or triggered by an innovation (e.g., public support for action on climate change).

-

Solving complex social and environmental problems and challenges: The field of social innovation places particular emphasis on two elements: (a) CAS have certain unique and defining features, and (b) social innovation for sustainability and climate change requires a deeper focus on human–environmental interactions.

In the context of social innovation to help solve challenges such as climate change, the complex systems category is useful because it suggests that solutions are discovered by developing a safe environment for experimentation. This experimentation allows us to discover important information that leads to the creation of new, emergent solutions. Evidence and knowledge are emergent through a probe-sense-respond process. Framing thinking on social innovation around the concept of the Anthropocene has led to an emerging belief (among scholars and practitioners) that “social innovation for sustainability lacks a deeper focus on human–environmental interactions and the related feedbacks, which will be necessary to understand and achieve large-scale change and transformations to global sustainability” (Olsson et al., 2017, p. 1) and “the social, environmental, and economic pillars often associated with sustainable development and ‘triple bottom line’ thinking have often led to trade-off decisions that either neglect the social-ecological, or strongly favor the economic” (p. 5).

Systems Innovation—The CCA Future

“Innovation-as-usual” – typically siloed and focused on “supplying” the market with technology-led solutions – is not delivering a 1.5-degree world. We need a new model of innovation to tackle climate change. . . one that is designed to generate options in the face of uncertainty and diversity, and to test for integrated and exponential solutions to address the complex, multi-faceted nature of the changes we need to make. . . . Using systems innovation as a key tool, our aim is to catalyze change in whole cities, regions, industries, and value chains by 2035. . . . Systems change not climate change.

Climate-KIC ( 2019 )

So how best to address the super-wicked problem of climate change? A consensus is emerging that the answer lies in the concept of systems innovation. Systems innovation takes the concepts introduced in this chapter thus far, builds on the premise of social innovation, and is then applied in the context of urgent needs for systems-level transformation.

The EIT Climate Knowledge and Innovation Community (Climate-KIC) is a European Union-funded climate innovation initiative and a leading proponent of systems innovation. Climate-KIC aims to identify and support innovation that helps society mitigate and adapt to climate change. They explicitly recognize that climate change is a complex problem and that individual innovations, projects, and organizations are unlikely to meet the challenge. Rather, their approach applies a portfolio logic: They construct “portfolios of engagement” on a particular issue or challenge, based on the understanding that some elements of the portfolio will succeed and some will naturally fail. Systems innovation in this context is driven by what they call levers of change. “Systems innovation is not limited to technological improvements. It acts on a wide array of change levers all at once, testing for possibility, connecting different approaches to learn from one another, looking for integrations, mash-ups, and exponential effects” (Climate-KIC, 2019).

Climate-KIC then aims to identify “early signals of potential systemic change” to identify which innovations to further support and ultimately scale. This approach is very similar to the original probe-sense-response approach proposed by Snowden. In the context of climate change, this means an early and continuous focus on learning to support adaptive management and identify replicable and scalable opportunities.

A second concept central to Climate-KIC are the levels of change. Complexity and systems dynamics are addressed by working at many levels, from district and city level to countries, regions, sectors, and value chains.

The evolution of the field of innovation, from a post-World War II focus on the institutionalization of government support for science and R&D to the present-day focus on social and systems innovation, has been complemented by and runs parallel to continuing advances in understanding and enabling international development. Resonating with the growing interest in and support for systems innovation approaches are a set of innovation for development principles more explicitly focused on understanding and addressing the root causes of poverty and inequality. The International Development Innovation Alliance (IDIA) has produced eight development innovation principles in practice (IDIA, 2019):

-

Principle 1. Promote inclusive innovation

-

Principle 2. Invest in locally driven solutions

-

Principle 3. Take intelligent risks

-

Principle 4. Use evidence to drive decision making

-

Principle 5. Learn quickly and iterate

-

Principle 6. Facilitate collaboration and co-creation

-

Principle 7. Identify scalable solutions

-

Principle 8. Integrate proven innovations

These eight principles can provide a blueprint for successful CCA when they are combined with a systems innovation approach, such as the Climate-KIC approach that proceeds from a portfolio logic, constructing portfolios of engagement on CCA as a particular challenge. In the next section, we explore the implications in terms of principles and approach for the MEL community—or at least for those practitioners who mainly focus on mainstream or established MEL approaches and methods.

MEL’s Role in Enabling Systems Innovation for CCA

This third part focuses on the key implications, ideas, and lessons for MEL practitioners working in CCA, drawing on the latest thinking and practice from systems innovation and innovation for development. These implications, ideas, and lessons are framed from the outset by the earlier mentioned three-step hypothesis.

We also provide in this section illustrative examples of innovative MEL approaches, processes, and technological interventions according to the major themes that have emerged from MEL to support a systems innovation approach to CCA. These examples have the potential to support enhanced MEL in CCA either through development in related fields or by being piloted in a current CCA context. The AF-TERG MEL study indicated that these cases have the potential to advance CCA MEL to better support a systems innovation approach to addressing climate change. It also suggested that they would enable the MEL community more broadly to better engage with, support, and advance a systems innovation approach to super-wicked problems.

Seven Directions of Change for the CCA MEL Community

-

1.

Promote and lead with a CCA systems innovation approach including better engaging with the key concepts of complex systems, super-wicked problems, the Anthropocene, and socioecological systems.

New terms and concepts are emerging in development discourse as fields such as systems innovation explore and more deeply define and understand global challenges and problems. With particular relevance to CCA, most prominent among these are the concepts of complex and adaptive systems, super-wicked problems, socioecological systems, the Anthropocene, and transformational change. Although the systems innovation community is pressing ahead in defining and exploring these concepts, they are not receiving consistent supported from the MEL community in terms of the critical MEL dimensions of these concepts—defining characteristics, indicator frameworks, and measurement approaches.

Taking transformational change as an example, we see little knowledge and consensus on defining, measuring, and assessing transformational change. The approach for CCA MEL practitioners should be to establish clear frameworks, pathways, and indicators for transformational change; establish an evidence base on which contexts and interventions are genuinely transformational (as opposed to other more incremental and iterative change processes); and develop relatively consistent indicator frameworks and measurement approaches to better assess and learn from transformational results.

-

2.

Engage better with participation, inclusivity, and voice in MEL.

The issues of genuine participation, inclusion, and voice have rightly taken on increased prominence in MEL theory and practice in recent years. This is particularly the case in CCA MEL where locally led adaptation/action (LLA)Footnote 8 has gained recognition because people and communities on the frontlines of climate change are often the most active and innovative in developing adaptation solutions. More broadly, evidence has shown that for development to be effective and sustainable, people who are vulnerable must be empowered and their voices heard, and gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is crucial to development progress, particularly in the context of CCA.

This commitment has been reaffirmed across the development space, perhaps most recently and prominently in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which commit to ensure “no one will be left behind” and to “endeavour to reach the furthest behind first” as overarching principles (United Nations General Assembly, 2015)Footnote 9 Organizations such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) are advancing evidence and education about the underlying factors that cause people to be left behind. In a recent paper, they outlined five critical factors: discrimination, geography, governance, socioeconomic status, and shocks and fragility (UNDP, 2018). Again, these critical factors resonate with the big issues being engaged with and explored by innovation for development communities.

The combination of three factors, prevalent in wider development policy and practice, have enabled advances in locally and/or citizen-led MEL. These factors have not yet been fully explored in the context of CCA:

-

1.

Demands for accountability – Increasingly energetic civil societies with a growing demand for greater transparency and public accountability

-

2.

More mature civil societies – With civil society increasingly willing and capable to participate in MEL processes

-

3.

The boom of information and communications technology (ICT) – Particularly in this context, the spread of internet and mobile phone technology

Out of these factors have emerged a number of citizen-led/citizen-generated data platforms, a prominent example being the Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI) Know Your City (KYC) initiative (SDI, 2018), which unites organized slum dwellers and local governments in partnerships anchored by community-led slum profiling, enumeration, and mapping. ICT-enabled participant reporting is not new to CCA programming but is still not widely included in the MEL components of programs. One likely reason is that it needs to be built into the design of the program itself from the onset rather than applied later as a MEL tool. The technology and tools are now proven, and cost and failure risks associated with ICT-enabled MEL have been reduced significantly over the last few years.

As such, MEL methods employing ICT should no longer be considered risky or unproven and citizen/participant reporting can provide data across the MEL cycle. ICT-enabled participant reporting as part of project monitoring can shift participants from passive beneficiaries of program activities to more active and empowered participants, reporting real-time reactions (positive and negative) to interaction with the program. On the accountability side, ICT-enabled participant reporting can generate data on program coverage and satisfaction. In terms of learning, open-ended questions such as “Provide an illustration of what you do differently as a result of the program” allow participants to demonstrate what a program may have enabled, often in video or photo form. Subjective reporting and learning are key areas that require further exploration, such as by asking participants about the extent to which they feel more able to cope and adapt to the threats posed by climate change as a result of the program. This goes to the heart of many CCA programs that aim to build adaptive capacity in target groups, removing the need to develop proxy indicators of adaptation and then generate data against them. The added advantage is that this type of reporting can be done before, during, and after a climatic shock or stress, and overlaid with shock/stress intensity data.

Linked to this but at a more systemic level is the issue of the decolonization of MEL. Launched in 2018, the South to South Evaluation Initiative (S2SE; African Evaluation Association, 2017) aims to elevate the substantial but underutilized indigenous knowledge, theory, and capacities of the Global South, and aims to reverse the asymmetries in decision making, resources, and knowledge in the global evaluation ecosystem. CCA MEL is a particular case in point: Global South perspectives, knowledge, and capacity go to the heart of not only MEL but also of appropriate and effective CCA. Far too often, evaluations are designed and led by those designated international experts and only supported by national experts. This immediately places southern experts, who tend to hold much deeper and more relevant insights into local contexts, challenges, opportunities, and practices, into a subordinate, lower value role and position. It perpetuates north-south power dynamics and ultimately results in lower quality, less insightful, and less useful evaluations.

-

3.

Overcome risk aversion in CCA and CCA MEL through field testing new, innovative, and often more risky MEL approaches.

The architecture, systems, and norms that are all pervasive in international development and CCA encourage risk aversion and the maintenance of traditional/established practices. This is the case in both CCA policy and programming and CCA MEL to support it. Despite increased recognition from the fields of complex systems and adaptive management that simple, boilerplate solutions are rarely appropriate for complex problems, an aversion remains to identifying and testing new and innovative solutions.

The fear of failure leads CCA agencies to take limited risks in their policy, programming, and MEL. This results in the perpetuation of established but often inappropriate approaches, methods, and tools. These agencies are motivated and incentivized more by accountability-driven evaluation processes than by trying less-tested and more innovative evaluative approaches, processes, and tools that may deliver rich, insightful, and useful new knowledge, but come with a higher risk of failure until they are established.

Hence, the MEL-system norm—fixed-term results reporting systems paired with traditional accountability-focused, postproject, mixed-methods evaluations—remains the staple of most large bilateral and multilateral agencies working on CCA. In this context of risk aversion, it is deemed better to have a safely delivered end-of-project evaluation that produces a long, unengaging (often unread) evaluation report with little or no real insight than to risk engaging a more innovative evaluation approach or method but one that carries a higher risk of failing.

The challenge is not to find new and innovative MEL approaches, methods, and tools for CCA; the challenge is finding the opportunity and resources to field-test them. Ways exist to reduce the risk of failure, such as combining established MEL methods with the piloting of new and innovative data collection and data analysis methods and tools. Much as the process of bricolage has gained popularity in systems innovation, so could the same process in MEL for CCA (Patton, 2020). For example, a project that aims to strengthen and then track household climate resilience through face-to-face household surveys could also pilot more subjective (how resilient household residents feel) and real-time results reporting through mobile phone-based participant reporting in the face of a climatic shock or stress.

-

4.

Demonstrate and promote the use of MEL to support and integrate adaptive management.

Recent years have seen an enhanced focus on adaptive management as the key concept at the heart of doing development differently. This is based on an increased recognition that development interventions are delivered in dynamic, unpredictable, and often contested contexts and systems; that in these contexts interventions need to be innovative; and that how best to deliver results in these contexts is uncertain. Therefore, operating effectively and efficiently in these contexts requires projects, programs, and institutions to be “adaptive.” This means

-

tailoring MEL systems, particularly monitoring systems, to generate robust evidence on program management and delivery;

-

a focus on lesson learning in close to real time to support course correction;

-

explicit focus on learning from unintended consequences and failures as well as from successes; and

-

portfolio learning and sense making among coalitions of similar stakeholders, both within and outside of the program context, supporting evidence and learning on both scalability and transferability (Pasanen & Barnett, 2019; Wild & Ramalingam, 2018).

Adaptive management focuses on intentionally building in opportunities for structured and collective reflection, ongoing and real-time learning, course correction, and decision making in order to improve effectiveness. This means that adaptive programs require, at project inception, intentional MEL design in which learning and course correction are integrated into the program from the start.

The concept of adaptive management should resonate particularly with CCA projects, programs, and organizations given that they share the same concept at heart. While it seems obvious that organizations promoting climate change adaptive programming should themselves be adaptive in their own designs, actions, and behaviors, evidence that CCA practitioners are leading the way is limited.

-

5.

Work across socioecological systems and scales.

A long-recognized, and largely unaddressed, challenge of the CCA MEL community is to develop and apply MEL approaches, methods, and capacities that integrate the social, economic, and environmental dimensions across systems and scales. At present, most MEL approaches tend to focus on individual domains—the human or the environmental/ecological domain—and not the interactions between them.

Earlier in this chapter, we introduced the concepts of super-wicked problems, complex adaptive systems (CAS), and the Anthropocene as critical, interrelated concepts that have a rising prominence in the context of CCA and with which the MEL community is beginning to engage. The fundamental issue underlying these concepts is the relationships among the social, economic, and environmental dimensions taking place in complex contexts and systems. In past development discourse, policy and practice has tended to focus on these elements in isolation and to prioritize the social and economic over the environmental.

Few CCA MEL frameworks systematically encourage a portfolio of indicators across all three domains—social, ecological, and economic. One potential solution would be to explicitly embrace a socioecological systems (SES) approach in CCA policy and program design. The SES approach describes the four essential dimensions (the natural system, livelihoods and people, institutions and governance, and external drivers) that provide the basis on which to situate and understand CCA results within a wider system. These also provide the basis for an MEL system based on the selection of a balanced set of CCA indicators under each dimension.

-

6.

Advance MEL approaches to better support systematic evidence and learning for scaling and replicability.

Given that the effects of climate change are being felt globally—across contexts, locations, and scales—learning what works, in what contexts, and why is particularly relevant for the CCA MEL community. Along with locally led learning, the CCA community has rightly put considerable emphasis on evidence and learning to support scaling and replicability. However, these two key concepts are not yet systematically integrated into MEL frameworks either as indicators or as key evaluation and learning questions or criteria.

Systems innovation approaches place particular emphasis on identifying, scaling, and replicating successful interventions, whether these are products, technologies, or processes. IDIA (2017) has devised a high-level process for scaling innovation in a development context, and this process is particularly important in the context of CCA. CCA MEL frameworks—from strategy and design (theories of change) through monitoring frameworks (indicators) to evaluation and learning (key evaluation criteria and learning questions)—should more deeply engage with the concepts of scaling and replicability as defined in a systems innovation approach.

-

7.

Adopt or develop MEL approaches, methods, and tools tailored to CCA systems innovation.

This final suggested direction engages more directly with the most appropriate MEL approaches, methods, and tools. Although several MEL approaches and frameworks aim to engage with scale, context, and system dynamics, the two most prominent are developmental evaluation (Patton, 2010) and its evolution into Blue Marble EvaluationFootnote 10 (Patton, 2020). Both approaches recognize some of the key issues raised in this chapter and Blue Marble Evaluation explicitly engages with systems innovation concepts. Blue Marble Evaluation is founded around four overarching principles and 12 operating principles. A simple starting point for any CCA MEL approach, system or method (whether for a project, program, organization, or institution) would be to assess which and how many of the Blue Marble principles it is coherent with or supports. Commissioners of CCA MEL services have a large role to play in encouraging Blue Marble (systems innovation) principles in the MEL terms of references they draft and the MEL services they fund. As made clear throughout the chapter, this is a new and emerging area that is gaining momentum. Its implications have yet to be explored and defined in the context of CCA.

The AF-TERG study has focused on innovative MEL approaches that attempt to reframe the role played by the MEL community, suggesting that the way MEL is approached and delivered needs to fundamentally shift. The rationale is that a fundamental shift in approach is required from the MEL community and practitioners, rather than a more granular focus on adopting and integrating the latest MEL technological innovations. Consequently, this chapter has given little attention to innovative MEL technologies, despite the subject of technology for MEL being the focus of considerable attention through networks and events such as MERL Tech. Technological innovation in MEL tends to be related to data under three overlapping themes: (a) data collection and capture technologies, (b) data analysis technologies including artificial intelligence and machine learning, and (c) data presentation and visualization technologies. The data collection and capture technologies can be broken down into three core areas: (a) big data, which includes satellite imaging and remote sensing; (b) information and communication technology (ICT); and (c) the internet of things.

Despite the slow uptake, technological innovations provide solutions to core challenges in MEL: reaching isolated groups; monitoring behavior change; collecting qualitative and subjective data; compiling, integrating, and interpreting multiple datasets; enhancing quality control; post evaluation verification; and finding robust samples for comparison. Examples of use in data collection include decentralized data gathering through self-reporting, online data harvesting, and the use of real-time data (Raftree, 2016, 2020). In terms of analysis, Bamberger and Mabry (2019) outlined several data analysis techniques with direct applications for program MEL. Bruce et al., (2020) added machine learning and artificial intelligence for text analytics as technological innovations to the toolbox of the MEL practitioner.

Finally, in terms of data visualization, processed data or MEL evidence needs to succinctly communicate complex problems and solutions. Visualizing and packaging data in a meaningful way across stakeholders is a challenge. The rapid pace of change in data technology will eventually and inevitably shape, drive, and inform MEL, especially from learning and data visualization perspectives. This may mean that instead of a traditional narrative report, MEL products and outputs could (and should) increasingly become digital, interactive, and more widely available.

What matters is not how technological innovations collect, analyze, or present data in isolation, but how they are integrated into innovative MEL approaches and methods to advance the delivery of CCA programming and understanding of CCA more broadly. This is the bricolage Michael Quinn Patton refers to in Blue Marble Evaluation. For this to happen, the MEL community needs to better engage with, exchange with, and understand the data scientists and technologists, and vice versa.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have argued that a systems innovation approach is required to address climate change adaptation, and that this in turn requires a fundamentally different and new approach from the CCA MEL community and practitioners. This new systems innovation approach in MEL would move the discipline in part away from the established static, uni-linear, project-program-country-region-bound MEL approaches, methods, and tools that have been standard practice for years. These traditional approaches, methods, and tools tend to be based on simple cause-effect results chains, tested ex-post through narrowly defined evaluation questions, and with established power relationships between evaluation commissioners, evaluation practitioners, participants, and intended audiences. They no longer reflect the dynamic complexity of super-wicked problems that define the Anthropocene: climate change, environmental degradation, and global pandemics.

Notes

- 1.

Wicked problems are difficult to clearly define, with understanding of the problem constantly evolving. They have many interdependencies, are often multicausal and socially complex, and exist in complex systems that exhibit unpredictable, emergent behavior. They usually have no right or wrong response, although responses might be worse or better; these problems cross governance boundaries, involve changing behavior, and are characterized by chronic policy failure (Rittel & Webber, 1973; Australian Public Service Commission, 2007). In the case of climate change as a super-wicked problem, time is running out, those who cause the problem also seek to provide a solution, the central authority needed to address the issues is weak or nonexistent, and irrational discounting occurs that pushes responses into the future (Levin et al., 2012).

- 2.

The authors recognize that a single, homogeneous MEL community does not exist. However, a consistent finding of the study is that mainstream or established MEL approaches and methods applied by the majority of MEL practitioners do not engage with the principles of systems innovation to address super-wicked problems. Only a small number of innovative MEL practitioners are already working on exploring MEL approaches that support systems innovation, with virtually none working in the context of CCA.

- 3.

Founder/director of the University College London Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

- 4.

Professor of psychology and public affairs emeritus at the Woodrow Wilson School, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology emeritus at Princeton University, and a fellow of the Center for Rationality at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

- 5.

(1933–2012) Distinguished professor, the Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science, and co-director of the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University; also research professor and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity at Arizona State University. Awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2009.

- 6.

J.W. McConnell Chair in Social Innovation at Waterloo University’s Institute for Social Innovation and Resilience.

- 7.

Westley’s keynote on the history of social innovation at Nesta’s Social Frontiers, November 14–15, 2013.

- 8.

- 9.

In addition to the overarching principle of “no one will be left behind,” SGD 5 aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls, and SDG 10 aims to reduce inequality within and among countries.

- 10.

References

African Evaluation Association. (2017). South to south evaluation (S2SE): A call to action. https://afrea.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/S2S_Brochure.pdf

Australian Public Service Commission. (2007). Tackling wicked problems: A public policy perspective. Australian Government. https://www.apsc.gov.au/tackling-wicked-problems-public-policy-perspective

Balint, P., Stewart, R., Desai, A., & Walters, L. (2011). Wicked environmental problems: Managing uncertainty and conflict. Springer.

Bamberger, M., & Mabry, L. (2019). Real world evaluation: Working under budget, data and political constraints (3rd ed.). Sage.

Bruce, K., Gandhi, V., & Vandelanotte, J. (2020). Emerging technologies and approaches in monitoring, evaluation, research, and learning for international development programs. MERL Tech. http://merltech.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/4_MERL_Emerging-Tech_FINAL_7.19.2020.pdf

Center for Social Innovation. (2020). Defining social innovation. Stanford Graduate School for Business. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/centers-initiatives/csi/defining-social-innovation

Climate Investment Funds. (2019). The CIF Transformational Change Learning Partnership: Pioneering joint learning to catalyze low-carbon, climate-resilient development. Climate Investment Funds Transformational Change Learning Partnership. https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/knowledge-documents/cif-transformational-change-learning-partnership-pioneering-joint-learning

Development Assistance Committee Working Party on Aid Evaluation. (2002). Glossary of key terms in evaluation and results based management. Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. http://www.oecd.org/development/evaluation/2754804.pdf

EIT Climate Knowledge and Innovation Community. (2019). Work with us to achieve net zero, in time. Funding systems change is today’s most important innovation. https://www.climate-kic.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/191029_EIT_Climate-KIC_FundingNetZero_Double.pdf

Everett, B., Barnett, C., & Verma, R. (2011). Evidence review – Environmental innovation prizes for development. DEW Point Enquiry No. A0405. DEW Point, the DFID Resource Centre for Environment, Water and Sanitation. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08abded915d622c00089b/61061-A0405EvidenceReviewEnvironmentalInnovationPrizesforDevelopmentFINAL.pdf

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2014). Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. IPCC Working Group II Contribution to AR5. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2/

International Development Innovation Alliance. (2017). Insights on scaling innovation. Author. https://www.idiainnovation.org/s/Insights-on-Scaling-Innovation.pdf

International Development Innovation Alliance. (2019). Development innovation principles in practice - insights and examples to bridge theory and action. Author. https://www.idiainnovation.org/s/8-Principles-of-Innovation_FNL.pdf

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., & Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the tragedy of super-wicked problems: Constraining our future selves to ameliorate global climate change. Policy Sciences, 45, 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

Olsson, P., Moore, M.-L., Westley, F., & McCarthy, D. (2017). The concept of the Anthropocene as a game-changer: A new context for social innovation and transformations to sustainability. Ecology and Society, 22(2), 31. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09310-220231

Pasanen, T., & Barnett, I. (2019). Supporting adaptive management: monitoring and evaluation tools and approaches (Working Paper 569). Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/odi-ml-adaptivemanagement-wp569-jan20.pdf

Patton, M. Q. (2010). Developmental evaluation: Applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. Guilford.

Patton, M. Q. (2020). Blue Marble evaluation: Premises and principles. Guilford.

Preiser, R. (2018). Key features of complex adaptive systems and practical implications for guiding action. GRAID by the Stockholm Resilience Centre. https://graid.earth/briefs/key-features-of-complex-adaptive-systems-and-practical-implications-for-guiding-action/

Raftree, L. (2016). ICTs in evaluation practice. https://lindaraftree.com/2016/05/31/icts-in-evaluation-practice/

Raftree, L. (2020). MERL Tech state of the field: The evolution of MERL Tech. MERL Tech. http://merltech.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/1_MERL_Tech-State-of-the-Field_FINAL_7.16.2020.pdf

Rittel, H. W. J., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation, and transformative change. Research Policy, 47(9), 1554–1567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.08.011

Slum/Shack Dwellers International. (2018). Know your city: Slum dwellers count. Author. https://knowyourcity.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/SDI_StateofSlums_LOW_FINAL.pdf

Snowden, D., & Boone, M. (2007, November). A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2007/11/a-leaders-framework-for-decision-making

Transformative Innovation Policy Consortium. (2018). Three frames for innovation. University of Sussex. http://www.tipconsortium.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/4173_TIPC_3frames.pdf

United Nations Development Programme. (2018). What does it mean to leave no one behind? A UNDP discussion paper and framework for implementation. Author. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Sustainable%20Development/2030%20Agenda/Discussion_Paper_LNOB_EN_lres.pdf

United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. Author. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

Wild, L., & Ramalingam, B. (2018). Building a global learning alliance on adaptive management. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12327.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gregorowski, R., Bours, D. (2022). Enabling Systems Innovation in Climate Change Adaptation: Exploring the Role for MEL. In: Uitto, J.I., Batra, G. (eds) Transformational Change for People and the Planet. Sustainable Development Goals Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78853-7_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78853-7_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-78852-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-78853-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)