Abstract

This chapter deals with the factorial structure of survey instruments for student perception of teaching quality. Often, high intercorrelations occur between different theoretically postulated teaching quality dimensions; other analyses point to a single unified factor in student perceptions of teaching quality, seemingly reflecting a “general impression” instead of a differentiated judgment. At the same time, findings from research on social judgment processes and from classroom research indicate that the teachers’ communion (warmth or cooperation) as well as students’ general subject interest can be important biasing factors in the sense of halo effects in student ratings of teaching quality. After presenting an overview of studies on the dimensionality of various survey instruments, we discuss whether aggregated data is impacted by an overall “general impression”. We confirmed this hypothesis using a sample of N = 1056 students from 50 secondary school classes. Moreover, this general impression could be explained at student and class level to a large extent by students’ perception of the teacher’s communion. Student general subject interest showed a medium effect but only at the individual level. These findings indicate that student perceptions of teaching quality dimensions are indeed influenced by a general impression which can be explained largely by teacher’s communion.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

An important precondition for using measurements of student perceptions of teaching is the validity of the collected data, both for use as informative feedback to teachers and for the collection of teaching quality within research studies. At the same time, measurements of student perceptions must be consistent with the theoretical assumptions made in the survey instrument with regard to professional competence or quality characteristics. While some other chapters of this volume deal with the question of perspective-specific characteristics of different feedback sources (Chap. 7 by Göllner et al. and Chap. 5 by van der Lans in this volume) or predictive validity (Chap. 6 by Schweig and Martinez in this volume), this chapter focuses on the extent to which students can actually distinguish between different theoretically postulated dimensions in their assessment of individual aspects of teaching. Subsequently, we examine whether the limited ability to differentiate can be explained by overlaying affective attitudes toward teaching or the teacher in the sense of a halo bias.

1.1 Dimensionality of Student Ratings on Teaching Quality

Usually, questionnaires are used to collect student perceptions of teaching, in which a certain number of quality dimensions are differentiated and surveyed separately. However, most of the used instruments show high correlations between the theoretically distinguished quality dimensions. This is also the case when the theoretically postulated structure is confirmed by a confirmatory factor analysis. For example, Krammer et al. (2019) reported intercorrelations ranging from r = .81–.95 between the three dimensions “instructional quality”, “teacher-student relationship”, and “performance monitoring” at student and class level. Analyses of the “students’ perceptions of instructional quality” (SPIQ) from Wisniewski et al. (2020) showed correlations from r = .63–.93 between the seven dimensions of the instrument. For primary schools, van der Scheer et al. (2019) reported correlations between r = .74 and r = .42 using an IRT model. One exception seems to be the survey instrument of Fauth et al. (2014), which only shows correlations between the dimensions of r = .47,.50, and.70 at the student and r = .23,.31, and.67 at the class level. However, a closer look reveals fundamental differences between item formulations of different quality dimensions. While the items of two of the dimensions start with “In our science class…”, the third one uses “Our science teacher…”.

Unfortunately, quite a number of the validation studies of student questionnaires on teaching quality did not report the correlations between the included scales (e.g. Bell & Aldridge, 2014; Tripod Education Partners, 2014), or they only tested the unidimensionality of single postulated scales (e.g. van Petegem et al., 2008).

At the same time, there are studies in which the theoretically postulated dimensions could be confirmed factor-analytically, but where they were highly charged with high standardized loadings to a latent second-order factor (e.g. Nelson et al., 2014 reports λ = .70–1.02).

A survey instrument which has been intensively analyzed in recent years is the “Tripod” questionnaire (Tripod Education Partners, 2014). Based on explorative factor analyses at the class level, the developers of the instrument postulate seven dimensions. However, in-depth analyses, which simultaneously take into account the nested multi-level structure with student and class level, consistently point to the unidimensionality of this questionnaire (Kuhfeld, 2017; Schweig, 2014; Wallace et al., 2016). A possible further dimension suggested by analyses is only weakly separated and is characterized by items with a certain type of item formulation (Kuhfeld, 2017). When examining other questionnaires, studies found unidimensionality for those with 16 items (Bijlsma et al., 2019) and 64 items (Maulana et al., 2015).

Overall, the question arises how to interpret the high statistical interrelations between theoretically well-distinguished dimensions of instructional quality in student surveys. A possible explanation, which we would like to examine in this chapter, is the impact of an affective overall attitude of students toward the teaching behavior of the evaluated teacher, resulting in biasing effects during the response process to individual items.

In research, different terms are used to describe the phenomenon whereby an overall attitude or impression influences and interferes with the assessment of individual teaching characteristics. For example, Clausen (2002) speaks of the effect of an “affective overall impression”, while other authors use the terms “halo effect” (e.g. Haladyna & Hess, 1994; Wagner, 2008) or “general impression halo” (Lance et al., 1994).

1.2 Possible Explanations for Halo Effects in Student Ratings

One promising path to a better insight into the phenomenon of high intercorrelations is to analyze the subjects’ processing of items. Tourangeau et al. (2000) divide the survey response process into four main cognitive components or steps. In the first step, comprehension, the respondent needs to understand the item and to identify its focus. In the subsequent retrieval step, the respondent has to generate a retrieval strategy and cues, retrieve specific and generic memories, and fill in missing details. Next, a judgment component on the retrieved memories regarding the completeness and relevance of different memories takes place, which ends with an estimation for the subject of the item. In the last step, the person gives a response in the requested way, e.g. marking the box with the answering option fitting best.

In case that an overall affective attitude of satisfaction is present throughout the survey answering process, this influences the retrieval and judgment of the information related to the items. Therefore, the rating on a particular aspect is a combination of the overall satisfaction of the person and the actual judgment of the particular aspect (Borg, 2003).

Applied to the situation of students, this would mean that ratings on particular aspects of teaching quality consist of a non-differentiating overall satisfaction with the teacher or class, and a rating component which concerns the particular aspect.

According to the findings from research on social judgments, overall judgments on other persons are based on two fundamental dimensions of perception (Abele et al., 2008; Bakan, 1966). The first dimension, often called “agency”, describes perception in terms of dominance, competence, or individualism. The second dimension, “communion”, refers to perception concerning warmth, cooperation, social and community orientation. In the overall judgment of other people, the perceived communion plays a dominant role and is responsible for much larger parts of variance in character judgments (Abele & Bruckmüller, 2011).

The discussion about the overall impression—which dominates the students’ judgments about teaching and teachers—points in a similar direction. A number of factors were discussed and examined which could well be subsumed under “communion”. Wallace et al. (2016, p. 1859), for example, interpreted the overall factor as a judgment of such forms of teacher interaction which “makes them feel safe, respected, and competent”. Kuhfeld (2017) explained the overall factor as an effect of students’ perception of teachers’ emotional support. Furthermore, findings also indicate that a higher teacher–student communion leads to higher desired learning behaviors of the students (Wubbels et al., 2015), and there is evidence of positive effects on learning achievement for learner-centered teaching approaches (Cornelius-White, 2007).

On the other hand, there are indications that an affective attitude toward the subject being taught could also cause biased ratings, and so the detection of an overall factor. In line with this assumption, findings from research on student ratings on teaching quality point to an influence of students’ general interest in the school subject on the perception of teaching (Ditton, 2002; Eder & Bergmann, 2004; Mayr, 2006; Rahn et al., 2019). Students’ general interest in the school subject is known to show a relatively stable pattern from secondary school onwards (Schurtz & Artelt, 2014), although current teaching characteristics may cause minor changes (Ferdinand, 2014; Lazarides et al., 2015). Findings from Rahn et al. (2019) point out that biasing effects of students’ general interest in the school subject vary considerably between different subjects, particularly with regards to the distinction between compulsory and optional courses. But as Ferdinand (2014) showed, these distortions seem to be largely neutralized in the aggregation of the student ratings of a class. Research findings from higher education also support biasing effects of the perception of the teacher as well as of the subject. For example, in the study by Greimel-Fuhrmann (2014) the interest in the subject and the teachers’ level of student orientation proved to be predictive for the students’ overall rating of teaching quality.

In summary, both the student-perceived communion of a teacher and the general interest in the subject could create an affective overall impression (Clausen, 2002), which as a “general impression halo” (Lance et al., 1994) overlays the student ratings of the individual quality dimensions. This could explain the low statistical separation between the dimensions of teaching quality. Therefore, in the following, we analyze the explainability of a halo bias in student ratings on teaching quality by these two factors in the context of secondary schools.

2 Empirical Part: Explaining Halo Effects in Student Ratings of Teaching Quality Through Students’ Perception of Teachers’ Communion and Interest in the Subject Being Taught

This study focuses on the following research questions:

-

RQ1: To what extent can an overlaying second-order factor in the sense of a general impression halo be modeled superordinately to the various dimensions of teaching quality?

-

RQ2: Can this second-order factor in student ratings on teaching quality be explained by a) teachers’ communion perceived by the students and/or b) students’ overall subject-specific interest?

-

RQ3: To what extent can the strength of the correlational structure between the different dimensions of teaching quality be reduced by controlling for one or both of these factors?

These research questions are addressed at the individual as well as at the class level.

2.1 Methods and Sample

2.1.1 Design and Sample

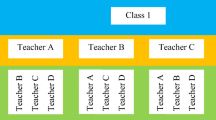

Data used for the following analyses were collected from different secondary schools in the southwestern part of Germany, where teachers obtained student feedback on their teaching and classes. For research purposes, student feedback questionnaires were supplemented by instruments for the survey of teachers’ communion and students’ general interest in subject taught by the teacher. The sample comprises a total of N = 1056 students from 50 classes at lower track schools (Werkrealschule, 9.6%), middle track schools (Realschule, 35.5%), grammar and high schools (Gymnasium, 49.6%), and secondary comprehensive schools (Gemeinschaftsschule, 5.3%). The students belong to grades 5–6 (28.0%), 7–8 (20.3%), 9–10 (30.6%), and 10–13 (21.1%), and are aged between 10 and 19 years. Teachers’ professional experience and gender were not surveyed for reasons of anonymity, but the sample included both young professionals and very experienced teachers, as well as female and male teachers. The teachers were free to choose the class and course in which they used the questionnaire. Therefore, the sample covers a wide range of taught subjects, including math, German, foreign languages, science, and history, but not physical education.

2.1.2 Measures

Feedback Questionnaire on Teaching Quality (FQTQ)

The Feedback Questionnaire on Teaching Quality (FQTQ, Röhl, 2015) is based on the characteristics of good teaching according to Meyer (2005), and includes 24 items with a four-level Likert format (“fully agree” to “disagree”). The aim of the instrument is to provide teachers with indications for improving their own teaching and classes. In total, the FQTQ assesses five quality dimensions of teaching: “Clarity of content and explanations”, “Activation and use of adaptive methods”, “Classroom and teaching management”, “Individual care and kindness”, and “Transparency of assessment” (see Table 1). All scales showed satisfactory to good reliability values using the reliability estimator ω (McDonald, 1999), which proved to be particularly reliable for use on short scales and in the context of structural equation modeling (Revelle & Zinbarg, 2009; Teo & Fan, 2013).Footnote 1 The formulations in the instrument are kept as low-inferent as possible (Wagner, 2008) and—in order to avoid problems of comprehension (Clausen, 2002)—are formulated positively throughout. In all quality dimensions, both ego- and web-references are used in the item wordings. Confirmatory factor analyses indicated a good fit of the theoretically assumed structure with five factors (χ2(242) = 1597.8, p < .001, CFI = .989, TLI = .987, RMSEA = .014). This was also evident in comparative analyses using a model with one single overall factor, which resulted in less favorable fit statistics (χ2(252) = 3591.7, p < .001, CFI = .923, TLI = .916, RMSEA = .069).

To survey the students’ perception of the “teacher communion”, the scales “CD: helping/friendly” and “CS: understanding” of the “Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction” (Wubbels & Levy, 1991) were used, which reflect a high degree of this basic dimension. The response scale for the 12 items comprises five levels (from “1: never” to “5: always”).

In addition, we measured students’ overall subject-related interest using the two items “The subject itself interests me” and “I like the subject itself”, using a five-point scale (from “very” to “not at all”).

2.1.3 Data Analysis

The data was analyzed by means of single- and multi-level structural equation analyses using MPlus 8.4 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012–2019). Considering the ordinal level of the four- and five-point rating scales, the “categorical” option was used for the measurement models, which relies on polychoric correlations for the corresponding sub-models. At the same time, the used procedure models response behavior in the sense of a probabilistic latent trait analysis (Uebersax, 2010–15). We chose the robust Weighted Least Square Estimator (WLSMR) as the estimation method, which showed a high reliability for ordinally scaled measurement models in simulation studies (Flora & Curran, 2004). The clustered data structure was considered by the option “type = complex”. The high number of parameters of the ordinal measurement models made it necessary to use the less computationally intensive Bayesian estimator for the subsequent multi-level analyses (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2012).

2.2 Findings

2.2.1 Modeling a Latent Second-Order Factor

To examine research question 1 (whether a factor overlaying the dimensions of teaching quality can be modeled reflecting an overall impression) an SEM was specified in which the overall impression is represented as a latent second-order factor. Fit indices pointed to a good fit of the assumed structure (χ2(247) = 414.7, p < .001, CFI = .978, TLI = .975, RMSEA = .021, SRMR = .040). Analyses indicated medium to large loadings of the five teaching quality dimensions on the second-order factor (clarity: β = .928, methods: β = .984, classroom management: β = .739, care: β = .878, transparency: β = .772, p < .001 each).

In the next step, the effects of the perceived communion of the teacher and students’ interest in subject on the overall impression factor were determined to answer research question 2. For this purpose, three regression models were estimated at the student level. First, both possible influencing factors were analyzed individually (models 1 and 2), and then combined in a second step (model 3). The results are summarized in Table 2.

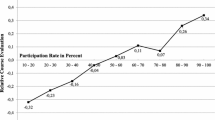

Model 1 examined the perceived teacher communion as an explanatory variable for the second-order factor overall impression. It shows a good model fit and explains more than 70% of the variance of the overall impression. A slightly inferior fit is shown by model 2, which tests students’ general interest in subject as the source for the overlaying effect and explains 40%. With the assumption underlying model 3 that both influencing factors jointly explain the overall impression, 76% of the variance can be explained (see Fig. 1). The far greater proportion can therefore be explained by the perceived teacher communion. Both factors correlate with each other on a medium level (r = .53).

2.2.2 Correlations Between Teaching Quality Dimensions Controlling for Students’ Perception of Teacher Communion

In order to analyze the effects on the intercorrelations between the various quality dimensions of teaching, the amount to which this can be explained by perceived teacher communion and general interest in subject was investigated analogous to the approach of Borg (2003) described above (research question 3). Therefore, a structural equation model was used to determine the direct effects of these factors on the items of teaching quality. This procedure extracted the variance component related to these factors, and only the remaining variance components were loaded onto the quality dimensions.

At the student level the model showed a good fit (χ2(291) = 477.3, RMSEA = .025, CFI = .979, TLI = 973, SRMR = .034). The loadings of the items on the quality dimensions remained (with two exceptions) significant (p < .05), but decreased substantially (average item loadings: clarity:.29, methods:.24, classroom management:.44, care:.21, transparency:.44). Whereas teacher communion showed highly significant effects on each of the 24 individual items, ranging from β = .21–.84 (p < .001), analysis of the general interest on subject revealed only eight much less significant effects (β = .10–.42, p < .05).

At the same time, the intercorrelations between the individual quality dimensions decreased substantially, and in some cases were no longer significant (Table 3). This is especially true for the dimensions “Individual Care and Kindness” and “Transparency of Assessment”, which showed no or only low correlations with the other dimensions. The partially negative correlations of the care dimension can be understood as a suppression effect, since this dimension has the highest content overlap with communion.

2.2.3 Analyses at the Class Level

With regard to the class level, model 3 was extended to a two-level model. The results on the effects at the student level remained almost constant compared to the previous findings. At the class level, the loadings of the individual teaching dimensions on the overall second-order factor showed similarly high values as at the student level (clarity: β = .86, methods: β = .95, classroom management: β = .60, care: β = .98, transparency: β = .67, p < .001 each). Interestingly, the effect of teacher communion on the overall factor was considerably higher (β = .87, p < .001), whereas interest on subject no longer showed any significant effect (β = .12, p = .198). Replicating the analysis of item-related effects of communion and general subject interest at the class level led to the almost complete elimination of significant item loadings on the dimensions of teaching quality.

3 Discussion

The findings presented here indicate that an overall impression which overlays the perception of teaching quality can be modeled as a latent second-order factor. The modeled overall impression can be explained to a large extent by teacher communion perceived by the students. Students’ general interest in the subject taught only shows significant effects at the individual level, and these effects are low. Thus, at the class level the general subject interest does not appear to have any relevant effect on the overall impression, and does not induce a bias for the assessment of teaching quality when the data is aggregated for classes. These results are in line with the findings from Ferdinand (2014). The findings also point to the existence of a “general impression halo” in accordance with Lance et al. (1994), which is based on an affective attitude—to a larger extent toward the teacher and to a lesser extent toward the subject being taught. Furthermore, the modest significant correlation between communion and interest in subject shows that there could be a reciprocal influence in students’ perceptions of the subject and the teacher.

Thus, the affective overall impression reported in the literature seems to be predominantly based on students’ perception of teachers’ communion, which means that the teacher is perceived as being interested in the learning progress of all students and sympathetic to the needs of the learning group. These results show that the theory of social judgments (Abele & Bruckmüller, 2011) provides a valid framework for obtaining a better understanding of the processes of students’ assessment of teaching and classes.

The control of direct item-related effects of teachers’ communion shows that the high intercorrelations of the dimensions of teaching quality in which the halo effect manifests itself can be drastically reduced—in some cases even to an insignificant level. For the general interest in the subject taught this is only true to a much smaller extent.

However, it can be theoretically argued that a high quality of teaching can indeed go hand in hand with students’ perception of a high teacher communion. In this case, students’ perception of a high communion of the teacher could be based on an inner attitude of respect and empathy from the teacher, which in turn contributes to an overall higher quality in the different teaching dimensions; conversely, a less empathic attitude from the teacher could lead to a lower quality of teaching (Tausch, 2007). Thus, this inner attitude could lead to teaching being better adapted to the students’ learning (from a methodological-didactical point of view), and also to a more comprehensible performance assessment for the students. Conversely, didactics and methodology which are more strongly oriented toward the students could lead to a higher assessment of teacher communion. In this case, the overlaying affective overall impression by the perceived teacher communion would not represent a problematic bias in the context of student feedback or the measurement of teaching quality. As a result of higher teaching quality, it is a central element for its valid measurement.

On the other hand, the perception of a high communion of a teacher could also lead to teaching which has qualitative deficits (with regard to pedagogical action in class) being assessed more positively by the students than might be appropriate. In this case, a weaker quality among teachers with a high communion would be masked by this perception. In other words, in such cases there could actually be a severe bias influencing the measurement of teaching quality. This could explain why many studies showed no or only minor predictive effects of the teaching quality measured by student surveys on learning achievement, and why often large differences in the quality perception of students and external observers are reported (see, for example, Chap. 7 by van der Lans in this volume; Fauth et al., 2014; Kuhfeld, 2017). If this is the case, a way out could be to control the perceived student communion through partial regressions, as was done in the analyses presented here.

However, both phenomena could also exist, which means that on the one hand there are good teachers with high communion and worse teachers with lower communion, for whom the effect described here is not a bias; on the other hand, there are also situations in which good teachers with lower communion are rated worse by the students and worse teachers with high communion are rated much better. In this case, there is a need to clarify whether indicators can be developed to distinguish between these two situations. These could then be used as a supplement to the classical evaluation procedure for feedback to teachers.

Further research is needed to address the issues raised in this chapter and, if necessary, to develop methods for correcting the measurement of teaching quality through student surveys. This would require longitudinal studies of the perceived quality of teaching over a period of joint work by teachers and classes. In such studies, it would be especially valuable if the dimensions of teaching quality and teacher communion were also assessed by external observers. At the same time, realizing experimental study designs could also be fruitful in which the same teacher’s statements with varying communion, e.g. as video vignettes with actors, are rated by students. In addition, studies controlling for the use of ego- and web-references in the item wordings could be helpful in getting a deeper insight into this effect (den Brok et al., 2006).

When using student ratings as classroom feedback, teachers should be aware that there is an overlaying halo effect related to their communion. Teachers perceived more positively by learners in this way should therefore be more critical of the feedback received. Conversely, relatively unfavorable ratings, which can be associated with a lower perception of communion, are an indication to consider and improve related aspects of teaching quality. For a reliable assessment and control of such effects, it would be advantageous to supplement the questionnaires on teaching quality used in practice and research with a scale for measuring the teacher communion perceived by the students. If such information is not available, teachers should bear in mind that the evaluation of the data at the individual level might be less confounded with their communion than the aggregated data at the classroom level. So, it might be advisable to evaluate the data on both levels to gain a better insight into how one’s teaching practice is perceived by the students.

Notes

- 1.

McDonald’s ω is based on the parameter estimates of the items in a factor model and represents the ratio of the variance due to the common factor to the total variance.

References

Abele, A. E., & Bruckmüller, S. (2011). The bigger one of the “Big Two”? Preferential processing of communal information. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,47, 935–948. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.03.028.

Abele, A. E., Cuddy, A. J. C., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2008). Fundamental dimensions of social judgment. European Journal of Social Psychology,38, 1063–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.574.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthen, B. (2012).Comparison of computational methods for high dimensional item factor analysis. http://statmodel.com/download/HighDimension.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr 2016.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: Isolation and communion in Western man. Beacon Press.

Bell, L. M., & Aldridge, J. M. (2014). Investigating the use of student perception data for teacher reflection and classroom improvement. Learning Environments Research,17, 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-014-9164-z.

Bijlsma, H. J. E., Visscher, A. J., Dobbelaer, M. J., & Veldkamp, B. P. (2019). Does smartphone-assisted student feedback affect teachers’ teaching quality? Technology, Pedagogy and Education,28, 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2019.1572534.

Borg, I. (2003). Affektiver Halo in Mitarbeiterbefragungen [Affective halo in staff surveys]. Zeitschrift Für Arbeits- Und Organisationspsychologie A&O,47, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1026//0932-4089.47.1.1.

Clausen, M. (2002). Unterrichtsqualität: eine Frage der Perspektive? Empirische Analysen zur Übereinstimmung, Konstrukt- und Kritieriumsvalidität [Teaching quality: A matter of perspective? Empirical analyses of agreement, construct and criterion validity]. Waxmann.

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research,77, 113–143. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298563.

den Brok, P., Brekelmans, M., & Wubbels, T. (2006). Multilevel issues in research using students’ perceptions of learning environments: The case of the Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction. Learning Environments Research,9, 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-006-9013-9.

Ditton, H. (2002). Lehrkräfte und Unterricht aus Schülersicht. Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung im Fach Mathematik [Teachers and teaching from a student perspective. Results from a study in Mathematics]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 48(2), 262–286.

Eder, F., & Bergmann, C. (2004). Der Einfluss von Interessen auf die Lehrer-Wahrnehmung von Schülerinnen und Schülern. Empirische Pädagogik,18(4), 410–430.

Fauth, B., Decristan, J., Rieser, S., Klieme, E., & Büttner, G. (2014). Student ratings of teaching quality in primary school: Dimensions and prediction of student outcomes. Learning and Instruction,29, 1–9.

Ferdinand, H. D. (2014). Entwicklung von Fachinteresse: Längsschnittstudie zu Interessenverläufen und Determinanten positiver Entwicklung in der Schule [Development of interest in subject: Longitudinal study of interest trajectories and determinants of positive development in school]. Waxmann.

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods,9, 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466.

Greimel-Fuhrmann, B. (2014). Students’ perception of teaching behaviour and its effect on evaluation. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education,5(1), 1557–1563.

Haladyna, T., & Hess, R. K. (1994). The detection and correction of bias in student ratings of instruction. Research in Higher Education,35, 669–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02497081.

Krammer, G., Pflanzl, B., & Mayr, J. (2019). Using students’ feedback for teacher education: Measurement invariance across pre-service teacher-rated and student-rated aspects of quality of teaching. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education,44, 596–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1525338.

Kuhfeld, M. R. (2017). When students grade their teachers: A validity analysis of the Tripod Student Survey. Educational Assessment,22, 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627197.2017.1381555.

Lance, C. E., LaPointe, J. A., & Stewart, A. M. (1994). A test of the context dependency of three causal models of halo rater error. Journal of Applied Psychology,79, 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.332.

Lazarides, R., Ittel, A., & Juang, L. (2015). Wahrgenommene Unterrichtsgestaltung und Interesse im Fach Mathematik von Schülerinnen und Schülern [Students’ perceived teaching style and interest in the subject of mathematics]. Unterrichtswissenschaft,43(1), 67–82.

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & van de Grift, W. (2015). Development and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring pre-service teachers’ teaching behaviour: A Rasch modelling approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement,26, 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.939198.

Mayr, J. (2006). Klassenführung in der Sekundarstufe II: Strategien und Muster erfolgreichen Lehrerhandelns [Classroom management in upper secondary schools: Strategies and patterns of successful teacher action]. Schweizerische Zeitschrift Für Bildungswissenschaften,28(2), 227–241.

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. L. Erlbaum Associates.

Meyer, H. (2005). Was ist guter Unterricht? [What is good teaching?] (2nd ed.). Cornelsen Scriptor.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2012–2019). MPlus (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

Nelson, P. M., Demers, J. A., & Christ, T. J. (2014). The Responsive Environmental Assessment for Classroom Teaching (REACT): The dimensionality of student perceptions of the instructional environment. School Psychology Quarterly,29, 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000049.

Rahn, S., Gruehn, S., Fuhrmann, C., & Keune, M. S. (2019). Schülerfeedback – fachübergreifend vergleichbar? [Is it adequate to compare students’ feedback beyond subjects?]. Unterrichtswissenschaft,47, 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42010-019-00043-w.

Revelle, W., & Zinbarg, R. E. (2009). Coefficients alpha, beta, omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika,74, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11336-008-9102-Z.

Röhl, S. (2015). Feedbackfragebogen zur Unterrichtsqualität (FFU) [Feedback Questionnaire on Teaching Quality (FQTQ)]. University of Education Freiburg.

Schurtz, I. M., & Artelt, C. (2014). Die Entwicklung des Fachinteresses Deutsch, Mathematik und Englisch in der Adoleszenz: Ein personenzentrierter Ansatz [The development of subject interest in German, mathematics, and English in adolescence: A person-centered approach]. Diskurs Kindheits- Und Jugendforschung,9(3), 285–301.

Schweig, J. D. (2014). Cross-level measurement invariance in school and classroom environment surveys. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,36, 259–280. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713509880.

Tausch, R. (2007). Lernförderliches Lehrerverhalten: Zwischenmenschliche Haltungen beeinflussen das fachliche und persönliche Lernen der Schüler [Teacher behaviors that promote learning: Interpersonal attitudes influence students’ subject and personal learning]. In W. Mutzeck (Ed.), Professionalisierung von Sonderpädagogen:Standards, Kompetenzen und Methoden (pp. 14–29, Beltz-Bibliothek). Beltz.

Teo, T., & Fan, X. (2013). Coefficient alpha and beyond: Issues and alternatives for educational research. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher,22, 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0075-z.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. A. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge University Press.

Tripod Education Partners. (2014). Tripod’s 7Cs: Technical manual.

Uebersax, J. S. (2010–15). The tetrachoric and polychoric correlation coefficients: Statistical methods for rater agreement. http://john-uebersax.com/stat/tetra.htm. Accessed 6 Apr 2016.

van der Scheer, E. A., Bijlsma, H. J. E., & Glas, C. A. W. (2019). Validity and reliability of student perceptions of teaching quality in primary education. School Effectiveness and School Improvement,30, 30–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539015.

van Petegem, P., Deneire, A., & de Maeyer, S. (2008). Evaluation and participation in secondary education: Designing and validating a self-evaluation instrument for teachers to solicit feedback from pupils. Studies in Educational Evaluation,34, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2008.07.002.

Wagner, W. (2008). Methodenprobleme bei der Analyse der Unterrichtswahrnehmung aus Schülersicht – am Beispiel der Studie DESI (Deutsch Englisch Schülerleistungen International) der Kultusministerkonferenz [Methodological problems in the analysis of classroom perception from the students’ point of view - using the example of the study DESI (Deutsch Englisch Schülerleistungen International) of the Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany]. Dissertation, University of Koblenz-Landau.

Wallace, T. L., Kelcey, B., & Ruzek, E. A. (2016). What can student perception surveys tell us about teaching? Empirically testing the underlying structure of the Tripod student perception survey. American Educational Research Journal,53, 1834–1868. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216671864.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., Dresel, M., & Daumiller, M. H. (2020). Obtaining students’ perceptions of instructional quality: Two-level structure and measurement invariance. Learning and Instruction. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101303.

Wubbels, T., Brekelmans, M., den Brok, P., Wijsman, L., Mainhard, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2015). Teacher–student relationships and classroom management. In E. T. Emmer & E. J. Sabornie (Eds.), Handbook of classroom management (2nd ed., pp. 363–386). Routledge.

Wubbels, T., & Levy, J. (1991). A comparison of interpersonal behavior of Dutch and American teachers. International Journal of Intercultural Relations,15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(91)90070-W.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Röhl, S., Rollett, W. (2021). Student Perceptions of Teaching Quality: Dimensionality and Halo Effects. In: Rollett, W., Bijlsma, H., Röhl, S. (eds) Student Feedback on Teaching in Schools. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75150-0_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75150-0_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-75149-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-75150-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)