Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of research on the evolution of residential segregation in Chinese cities since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. There were almost no discernible patterns of segregation during the central planning period, largely due to the socialist work-unit systems and the de-commodification of land and housing. Since the initiation of economic reforms in 1978, Chinese cities have witnessed significant spatial divisions across socioeconomic groups, driven by forces such as rapid economic and spatial restructuring, market-oriented housing and land reforms, and massive rural-to-urban migration. Residents of similar socio-economic status tend to cluster in the same neighbourhoods, with the elite moving to expensive gated communities and the urban poor to dilapidated residential areas. The impacts of segregation on residents’ social contacts and labour market outcomes are profound and long-lasting. While social segregation is regarded as a widespread urban phenomenon worldwide, the causes and consequences of segregation in Chinese cities should be interpreted within the country’s specific historical, social, cultural and institutional contexts.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

In common with other transitional societies, China has experienced significant transformations of urban landscapes during the shift from a centrally planned economy to a market one. Before 1978, most urban residents were employed in work units and lived in houses allocated by these units in relatively stable and homogenous neighbourhoods close to workplaces (Wang and Murie 1999). Cities were characterised by mixed neighbourhoods without discernible patterns of segregation (Bray 2005; Lo 1994). The subsequent economic reforms have resulted in significant socio-economic stratification and spatial divisions (Li and Wu 2008). Housing reforms privatised most work-unit housing and facilitated the development of a booming real estate market, which provided options for wealthy people to purchase commercial properties of high quality, leading to income-based spatial sorting (see Chap. 12 on residential sorting and Chap. 9 on housing market reform). Land reforms resulted in unprecedented urban sprawl, creating new industrial zones and residential compounds in suburban areas. Urban renewal projects have tended to gentrify the city centre leading to the relocation of millions of residents to suburban areas either voluntarily or against their will. Meanwhile, a large number of migrants have moved to cities to seek job opportunities and a better life. Most of them are concentrated in low-skilled jobs and live in poorer areas or migrant enclaves. Urban neighbourhoods have shifted from being ‘work-based’ to ‘residence-based’ and from mixed communities to those of residents of similar socio-economic status (Wang 2000).

Numerous studies have examined the causes, processes, extent and consequences of urban segregation in China (Li and Wu 2008; Wu et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2019; Shen and Xiao 2019). This chapter aims to provide an overview of research on residential segregation in Chinese cities, with the focus on both the driving forces behind it as well as its profound impacts on society. Segregation refers to ‘the processes of social differentiation and the resulting unequal distribution of population groups across space’ (Madrazo and van Kempen 2012, p. 159; see also further discussion of segregation concepts in Chaps. 2 and 10). As the geographic distribution of resources and opportunities is unevenly distributed, segregation is likely to influence people’s access to resources, and subsequently their contact with other social groups, social networks and labour market opportunities. An overview of existing knowledge on the driving forces, extent and consequences of segregation in Chinese cities can provide rich insights into the life experiences of urban dwellers during the transitional process. It is also useful to predict the future trends of urban transformations in China to inform policy development.

Levels of urban segregation have been researched in various countries and are generally agreed to be a widespread global phenomenon. The extent and nature of such segregation vary according to the particular groups affected, the way it is measured and the historical, cultural and institutional contexts. In this chapter, we first provide background information by discussing neighbourhood arrangements in China’s central planning period (1949–1978). Then we proceed to discuss the driving forces of neighbourhood changes and segregation during the reform era (post-1978). This is followed by a review of the extent and measurement of segregation in Chinese cities. Finally, we explore the consequences of urban segregation in terms of social contact and labour market outcomes in the specific context of Chinese transitional cities.

2 Urban Segregation During the Central Planning Period

During the central planning period, the government’s egalitarian policies tried to reduce socio-economic inequalities and to create a ‘classless’ urban society (Wu and Li 2005). The majority of urban workers was employed in work units, which were social organisations established under state socialism to provide employees not only with lifetime jobs but also a comprehensive package of social benefits and services including nursery, medical care and pension (Bray 2005). The metaphorical term ‘iron rice bowl’ was coined to indicate the continuity and stability of state employment. Income differences were minimal. Cities were characterised by a high degree of social homogeneity, a work-unit-based cellular structure, and mixed neighbourhoods without noticeable patterns of spatial segregation (Lo 1994). There was no private land or housing market. All urban land belonged to the state and was allocated to various land users according to the central planning system. Housing was regarded as a form of social welfare. The de-commodification of housing and land, an embodiment of a centrally planned economy, is said to be shaped by both ideological considerations and development strategies (Chen and Han 2014).

In the early 1950s, many private houses were transferred to local governments as part of the nationalised wealth redistribution process. The majority of urban residents lived in houses allocated by their work units, which were responsible for constructing, allocating and maintaining accommodation. Work-unit housing accounted for about 60% of the total urban housing stock in 1978, a figure much higher than that in former socialist countries such as Hungary (Kirkby 1985). The municipal housing bureaux provided housing to those few who did not have a work unit. Only 20–25% of the urban housing stock was owner-occupied (Huang 2004). Most work-unit housing was constructed near workplaces, forming cellular neighbourhoods. They became self-contained spatial units with mixed land use for workplace, residential areas and social services such as nursery and medical centres. Jobs and housing were, therefore, linked together, enabling workers to minimise their journey to work. Housing costs formed part of the total costs of the work unit who then bargained with their supervisory government agents for investment to develop and manage housing.

Work-unit compounds provided the basic urban structure of a socialist city. Their spatial distribution relied on urban land use under the central planning system. Within each work-unit compound, housing allocation was based on non-pecuniary criteria such as seniority, rank and family needs (Wang and Murie 1999). Managers and workers, regardless of their occupation and social status, lived in the same residential areas close to their workplace. As a consequence, people’s residential locations depended on proximity to the workplace rather than personal characteristics such as income (Logan et al. 2009). It is claimed that ‘social areas in the pre-reform era were mainly built upon different land uses rather than social stratification’ (Li and Wu 2008, p. 406).

Despite the socialist ideology, there were inequalities among work units, which differed according to their economic and political strength. Those producing strategic products for the state (e.g. large steel companies) or those with higher administrative ranking (e.g. provincial-level state-owned enterprises) had more bargaining powers when they negotiated with supervisory government agents for resources and investments. They, therefore, had a greater capacity for investment in housing within their work-unit compounds. Powerful work units provided better facilities and residential environments for their employees, while others, such as smaller units or those with performance problems, might experience housing shortage and deterioration. It is apparent that during the central planning period, housing inequalities between work units exceeded those within work units (Wang 2000). Despite this, workers in the same work unit lived in the same residential area and were spatially mixed—that is, workers of different rank were not segregated by their residential location. Spatial segregation was limited though it is hard to say whether there were other forms of segregation as described in Chap. 2, such as friendship stratification by social status.

3 Socio-Spatial Differentiation and the Driving Forces After 1978

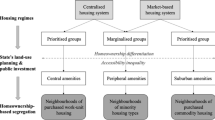

Chinese cities experienced dramatic transformation and socio-spatial differentiation since the initiation of the economic reforms in 1978. This has significantly changed the socialist egalitarian allocation of urban space, with emerging segregation among different social groups. Economic reforms have increased income disparity (Bian and Zhang 2002). Whilst the middle class and the elite have been on the rise, a significant group of urban poor has emerged. Jobs were no longer allocated by the government. Millions of workers were laid off from state-owned enterprises as a result of economic restructuring. Rural migrants who moved to cities to work in low-skilled jobs also swelled the ranks of the urban poor (Wu et al. 2013). Accordingly, a new social-spatial structure has emerged with the elite concentrated in expensive gated communities and the urban poor in run-down neighbourhoods such as old work-unit compounds, residential areas awaiting regeneration and urban villages (Huang 2004; see also Chap. 6). It is widely acknowledged that socioeconomic status, housing market discrimination and economic restructuring are the main drivers of segregation in Western cities (Madrazo and Van Kempen 2012). In the Chinese context, the role of institutional factors has been highlighted as one of the major drivers in shaping socio-spatial segregation. Scholars agree that segregation results from the joint efforts of market forces and institutions (Li and Wu 2008; He 2010). Such institutional factors include housing reforms, the land system and the household registration (hukou) system, all of which significantly influence individuals’ access to social services, resources and opportunities.

China’s housing system has experienced significant changes as a result of pro-market housing reforms, which promote homeownership and stratify the socio-economic structure (Wang and Murie 1999; Huang 2004). Housing reforms initiated in the early 1980s aimed to establish a functional housing market by privatising existing work unit housing stock and developing a real estate market. Through a process of trial and error in selected cities, housing privatisation was gradually rolled out across the country where existing work unit housing was sold to occupants at a heavily discounted price. The construction and allocation of work-unit housing coexisted with commercial properties until 1998 when the welfare distribution of housing was abolished. Since then, most people who were not allocated a house through their work unit have had to purchase housing via the market. However, some large and powerful work units, such as government and public institutions, continue building or providing subsidised housing to their key workers, resulting in persistent patterns of residential stratification. The housing privatisation process led to enormous housing inequality. People who enjoyed better-allocated housing before 1998, including those with higher political ranks in work units, gained more benefits by purchasing their property at a low price (Wang 2000). A subsequent booming housing market has further exacerbated housing differentiation and inequality (Logan et al. 2009). The market provides more housing choices, including high-quality commercial properties with access to improved facilities and infrastructure. People with high income then move away from their previous work-unit compounds or run-down areas to high-quality housing, leaving those who were unable to move in poorer residential areas. Rising house prices in many cities has led to serious housing affordability problems. In contrast with the rapid development of a real estate market (Chap. 9), the subsidised housing sector targeting low- and moderate-income households has lagged behind. The government has introduced mitigating schemes, such as the Economic and Comfortable Housing and the Affordable Rental Housing programmes (Huang 2012). However, both governments and real estate developers are reluctant to construct subsidised housing due to its low profitability and its great drain on public finance. Many subsidised housing units are located in suburban areas without sufficient public facilities and services. They become less desirable residential areas. The housing reforms have resulted in clusters of residents with similar socio-economic status becoming concentrated in certain neighbourhoods.

Along with the housing reforms, an urban land market has gradually evolved, as the government separates the ownership and use rights of urban land. This enables entrepreneurial urban governments to take control of land under their jurisdiction and to lease land use rights to finance local urban development. Many cities have experienced rapid urban sprawl, with new industrial zones and residential housing in suburban areas, to take advantage of cheaper land there. Urban sprawl in China differs from the pattern in the USA where residential sorting results in a decayed city centre surrounded by affluent suburbs. In the Chinese context, local urban governments play an important role in promoting urban land sprawl in order to develop the local economy. However, in many cases, they fail to synchronise the development of high-quality facilities and services such as hospitals and schools, which remain located in the city centre (Chen and Yeh 2019). Suburban living is associated with low service accessibility, especially for people without cars.

In the meantime, neighbourhoods in the inner city have witnessed enormous physical and socio-economic changes. A large number of new buildings have been constructed since the mid-1980s, and now form the majority of the current urban housing stock (Li and Huang 2006). Massive urban renewal projects demolished many work-unit compounds and neighbourhoods of pre-1949 origin and replaced them with glossy offices and luxurious apartments. For example, 280,000 homes in inner city Beijing were torn down in the 1990s, and 605,000 more were demolished in the 2000s (Liu and Wong 2015). Numerous residents lost their original homes and had to be accommodated elsewhere. Those who could not afford commercial properties in their original location were forced to move to resettlement housing in the city fringe with poor amenities (Fang 2006). Many urban renewal projects have gentrified the city centre and significantly changed the socio-economic composition of residents in those neighbourhoods (He 2010).

Since 1978, hundreds of millions of migrants have moved from their places of origin into the cities to seek jobs and a better life. Three quarters of them originate from the countryside. As they lack local household registration (hukou) status, they face many barriers and constraints. The hukou system, implemented in 1958, is a social control measure that requires all Chinese citizens to register with either agricultural or non-agricultural hukou status in a particular place inherited from their parents. Holders of hukou registration in different places are entitled to different social benefits and services. Those with local urban hukou status have access to better public services than migrants, and residents in larger cities are entitled to even better services (e.g. high-quality health and education) than those in smaller cities (Chan 2009). Despite the gradual relaxation of migration control and years of reforms of the hukou system, most migrants are unable to get local hukou status after they have moved to live and work in the city. Without local urban hukou status, migrants are denied access to many local social benefits and services, such as subsidised housing, unemployment insurance and even schooling for their children in local authority schools in some cities (Wu 2002).

There is a huge heterogeneity among migrants in terms of their educational qualifications, skills and career prospects. Many migrants, especially those originating from the countryside, are concentrated in low-skilled jobs in manufacturing factories, construction and service sectors. They live in poor urban neighbourhoods, particularly urban villages, which provide low-cost housing and gradually become enclaves where migrants develop social networks and create job opportunities. Informal structures and ambiguities arise around land property rights due to illegal building extensions, lax land management and development control, overcrowding, and informal and insufficient service provision (Wu et al. 2013). An urban village represents an example of segregated urban space, which we shall discuss in more detail in the next section and in Chap. 6.

4 The Measurement of Segregation in Chinese Cities

In contrast with segregation studies in Western countries which often focus on race and ethnicity, segregation in Chinese cities is based on socio-economic status. This is partly because non-Han ethnic minorities account for a small proportion of the Chinese population (8.5% in 2015) and most of them are concentrated in western and northern regions (NSB 2016). Most studies on urban China are conducted in coastal or large cities where the number of non-Han ethnic minorities is extremely small when compared with the Han majority. A good range of methods have been employed to measure segregation in terms of socio-economic status in urban China, including index-based measurements (e.g. dissimilarity index), profiles of clusters, multi-scale analysis, activity space analysis and spatial-social network analysis. Studies use different spatial scales, such as predefined administrative spatial units, i.e. residential committee (juweihui in Chinese), sub-district (jiedao) and district (qu), as well as residential blocks. Moreover, individual survey data are used in activity space analysis and spatial-social network analysis, as we shall discuss later in this section (see Part III of the book for proposed new methods in Chinese segregation research). There is a consensus across existing studies that the level of segregation in Chinese cities has increased dramatically since the initiation of the economic reforms.

As segregation is usually regarded as a spatial issue, index-based measurements are widely used in segregation studies to measure the concentration of a particular group in given spatial units using census data (e.g., Duncan and Duncan 1955; see methods review in Chap. 2). For example, Zhao (2013) uses the census data in Beijing for 1990, 2000 and 2005 to calculate the indices of social segregation and finds that residential segregation increased significantly over these years. Wu et al. (2014) use the 2000 census data at the residential committee level in Nanjing and develop profiles of residential clusters. Their findings reveal clear patterns of segregation between affluent and poor social groups. Li and Wu (2008) agree that segregation of social groups emerged in Chinese cities, though the extent was much lower than that in the USA or UK. Using 2000 census data in Shanghai, the authors examine the dissimilarity index in terms of housing tenure, educational attainment, hukou status and location (centre versus suburb). They find that the most significant residential segregation was based on housing tenure. This finding is supported by Sun et al. (2017) who reported significant residential differentiation among different housing tenure types in the coastal city of Xiamen. Similar conclusions are reached in studies based on the Western contexts which maintain that housing tenure is significantly associated with segregation because the supply and location of different housing types influence people’s housing choices and so lead to the spatial concentration of specific social groups (van Kempen and van Weesep 1998). However, as Li and Wu (2008) rightly point out, tenure-based segregation in China in the late 1990s and early 2000 mainly resulted from pre-existing institutional privileges rather than households’ housing preferences. A subsequent study by Shen and Xiao (2019) examined the changes in residential segregation in Shanghai using census data from 2000 and 2010 at the residential committee level. They found the city had become more divided in terms of socio-economic status over the decade, and significant segregation existed in terms of educational attainment and hukou status, besides the division between central and suburban locations. The extent of segregation in terms of educational attainment exceeded that based on hukou status. While the authors acknowledge the impact of institutional factors on urban segregation, they argue for the growing importance of the role of human capital and market forces in shaping socio-economic segregation.

Using the 2010 census data at an individual level in Shanghai, Liu et al. (2019) find the spatial unevenness of the migrant residential distribution is much more evident in smaller geographic units such as residential committee levels than larger geographic units: where the top 10% of migrant-concentrated neighbourhoods had a migrant share higher than 75% and the bottom 10% were at 12% or below. Liu et al. (2019) also show significant differential patterns of segregation among people with different hukou status; in particular, rural migrants tend to cluster rather more than local residents and urban migrants, with most of them concentrated in the outskirts of the city. The significant differences in residential segregation between migrants and local residents are also found in the cities of Guangzhou (Liu et al. 2015), Wuhan (Huang and Yi 2009) and Shenzhen (Hao 2015). Many migrants live in urban villages, dilapidated neighbourhoods and factory dormitories, away from local residents.

Besides considering the census data, some studies have examined the spatial distribution of residents of different socio-economic status using more finely-grained block-level data. Liu et al. (2018b) provide such an example, by using the 2005 and 2010 Beijing Travel Survey, which recorded 24-h travel diaries from 210,000 individuals in 2005 and 116,000 in 2010. The authors studied the socio-spatial changes in central Beijing at the scale of Traffic Analysis Zones (TAZs), which are derived according to the road networks by the Beijing Municipal Commission of Transport. The spatial scale is similar to the size of a block, much finer than that of a residential committee. By employing latent class analysis and GIS visualisation, the authors show that 90% of the blocks in the study had over 10% change in the social stratification index of their residents. It is generally agreed that the extent of segregation at a lower spatial scale tends to be larger than that at a higher one (Duncan and Duncan, 1955; Sun et al. 2017), though recent research has challenged this (Manley et al. 2019).

Segregation may occur in people’s activity space outside home, including the workplace, shopping and leisure, which are regarded as other anchor points for daily activities (see Chap. 2). The analysis of segregation based on activity space represents an alternative method of examining segregation through a people-based approach rather than the conventional place-based method. The rationale is that activity space may influence individuals’ use of urban space and facilities as well as their social contact. Studies have used surveys, travel diaries or participant observation to examine individuals’ activity space in daily life. For example, Lin and Gaubatz (2017) employ an ethnographic method to record migrants’ daily social and spatial interactions with urban spaces, including work, shopping, leisure activities and social contacts in the city of Wenzhou. They find that migrants are constrained in their activity space as they have limited interaction with local people and little access to urban amenities beyond their residential area, which is close to their manufacturing factories. The study echoes findings of various significant patterns of segregation between migrants and local residents from research work using index-based segregation measurements such as RCQ (residential concentration quotient) (e.g. Liu et al. 2019).

Wang et al. (2012) used a travel survey of over l,000 residents in 10 different neighbourhoods in Beijing to examine people’s actual use of space in their daily life for residents living both inside and outside privileged gated communities. Their results show socio-spatial differentiation beyond residential spaces in terms of employment, consumption patterns, leisure and social relations. A similar conclusion was reached by Zhou et al. (2015), which examined the out-of-home activities of residents in Guangzhou and found a significantly different activity space between higher and lower income groups. Similar patterns have been observed in terms of ethnic segregation. Despite the low dissimilation index indicating residential mixing between the ethnic minorities and the Han majorities in administrative spatial units, Tan et al. (2017) revealed significantly different space–time patterns within daily activities between the Han majority and the Hui minority in the city of Xining in western China. The authors explain the differences in terms of the particular religious activities of the Hui minority and Hui women’s limited participation in out-of-home activities. The results show that the dissimilarity index is likely to underestimate the actual degree of social segregation.

Similarly, Zhao and Wang (2018) reported different everyday activities between migrants and local residents in an urban village in Guangzhou, despite the fact that the two groups lived in exactly the same residential area. Using socio-spatial network analysis, the authors found that local residents socialise more with other locals, visit pubs and send their children to publicly funded kindergartens, while migrants have more contact within their own group, visit roadside food stalls and small chemist shops and send their children to migrant kindergartens. There was only a modest interaction between the two groups, suggesting levels of segregation that are not captured by index-based segregation measurements.

Various residential enclaves are discernible in Chinese cities. Two of the most noticeable are urban villages and gated communities comprising commercial properties. Urban villages are rural settlements that were engulfed by rapid urban expansion (see Chap. 6). As the compensation of expropriating residential land is much higher than that of agricultural land, local urban governments expropriated agricultural land for development and left residential land in the village. Due to their convenient location and the rising job opportunities that accompany urban sprawl, many migrants flooded into urban villages for affordable housing. Local villagers took the opportunity to extend their houses and rent them to incoming migrants to supplement their income after the loss of their agricultural land. In most urban villages, migrants outnumber local residents. Urban villages are characterised by sub-standard housing, overcrowding, lack of sanitary facilities and public services. They do, however, provide low-cost housing and an entry point for many migrants who develop livelihoods and social networks in the city. A range of institutional factors create significant levels of differentiation between local residents and migrants. Local residents are entitled to local social benefits and services, as well as extra benefits provided by their collective assets, while migrants are treated as ‘outsiders’ as they do not have local hukou status (Du et al. 2018). Urban villages as migrant enclaves strongly reflect residential segregation. However, some villages, such as those in Shenzhen, are located near the city centre thereby providing opportunities for migrants to access amenities (Hao 2015). If segregation is measured at a larger spatial scale, urban villages will actually reduce the level of segregation by providing low-cost housing for migrants in central areas.

As another typical enclave in Chinese cities, gated communities provide quality residential space for people who can afford them. The physical barriers such as gates, and the higher socio-economic status of residents both contribute to social segregation. It is important to note, however, that gated commercial properties vary hugely in terms of the quality of the residential environment and the extent of exclusiveness in Chinese cities. The impacts of gated communities on social contact are contingent on local context, as we shall discuss in detail in the next section.

5 The Consequences of Segregation in Chinese Cities

Segregation is likely to have important consequences for individuals’ life chances and opportunities because it affects their access to resources, amenities and the benefits of wider social networks (Granovetter’s 1983 ‘strength of weak ties’ argument; see also Chaps. 11 and 15). While there are positive consequences of spatial concentration for people of the same social group, such as the ability to network effectively, many studies based on Western contexts document the negative effects of segregation (van Kempen and Murie 2009). For example, living in a neighbourhood with large numbers of ethnic groups tends to be associated with poverty and unemployment. Segregation is likely to reduce contact between ethnic minorities and the majority, leading to social exclusion. This might be detrimental to the integration of ethnic minorities into mainstream society. However, as Kaplan and Holloway (2001, p. 62) rightly point out, ‘people may be victimised by space or they may utilise space, and this can change with time. Specific accounts must negotiate the tension between the marginalising and empowering impacts of segregation’. The impacts of segregation on people’s life are contingent on local contexts and personal characteristics. We discuss the consequences of segregation in Chinese cities through the perspectives of social contact and labour market outcomes.

5.1 The Impacts on Social Contact

An important mechanism under which segregation influences life chances is through social contact. Living in a migrant enclave might reduce social contact between migrants and local residents. There are studies showing different activity space and limited interaction between migrants and local residents in an urban village (Zhao and Wang 2018). Residential segregation may also influence peoples’ perception about different social groups. Using data from a survey in Shanghai in 2012, Liu et al. (2018a) examine migrants’ and local residents’ perceptions of social integration and find that migrants living in neighbourhoods with a larger migrant population size are more likely to think that they are excluded by local residents. Based on a large national micro-level data extracted from the 2014 China Migrant Dynamic Survey, Zou et al. (2020) find neighbourhood types correlate with migrants’ socio-economic integration but there is broad heterogeneity in the correlations across different migrant groups. In particular, migrants living in urban villages show significantly lower levels of overall socio-economic integration than those living in formal urban neighbourhoods such as work-unit compounds and commercial properties. Through interviews with migrants living in urban villages, Du et al. (2018) reported that many migrants agreed that they were treated as ‘outsiders’ in the locality, because they were excluded from many local benefits and services, which are only reserved for those with local hukou status.

However, Wang et al. (2016) argue that urban villages per se do not prevent migrants from interacting with local residents. Using a survey of 1370 questionnaires from Nanjing, the authors examined the impacts of hukou status and residential characteristics on neighbourhood interaction between different social groups. They found that migrants are more likely to interact with other migrant neighbours than longer term local residents. Open spaces, particularly in deprived neighbourhoods and urban villages, facilitate residents’ interaction with their immediate neighbours. These neighbourhoods have a higher level of intergroup social contact than commercial housing estates. The finding is supported by Forrest and Yip (2007) who reported that social contact is more frequent in old neighbourhoods or work-unit compounds than in commercial property estates where privacy is most valued. According to another study based on a 1420 questionnaire survey in Shanghai in 2013, Wang et al. (2017) found that the concentration of migrants in a neighbourhood does not reduce neighbourhood cohesion, which is measured by social solidarity, common values, social networks, a sense of belonging and informal social control. These findings support the conclusion that urban villages do not prevent migrants from interacting with local neighbours. However, it is unknown whether the experience of living in an enclave influences migrants’ social interaction with local residents residing outside urban villages, especially those living in formal urban neighbourhoods such as commercial properties.

Gated commercial estates represent another of enclave within Chinese cities. Most studies of gated communities in the Western context focus on their negative impacts on social contact between different social groups, such as the exclusion of underprivileged people and limits on social contact (Atkinson and Flint 2004). In the Chinese context, gates and walls have always been features of the urban landscape (Wu 2005). Traditional Chinese cities were walled and gated. Within the residential areas, courtyard houses were characterised by walls and collective living space. During the period of state socialism, Maoist cities were replete with walls and gates that defined the boundaries of self-contained work-unit compounds, which accommodated both managers and ordinary workers. After the economic reforms, newly constructed commercial properties often have gates to separate themselves from busy streets and other public spaces. In recent years, there is a push for closed community management in terms of neighbourhood governance in certain cities. Any interpretation of gated community within Chinese cities should, therefore, take this tradition into account.

The impacts of a gated community on social contact and life opportunities are contingent on local social and cultural contexts. There are studies that do report the negative impacts of gated commercial estates. For example, drawing on data from a retrospective questionnaire survey in three gated estates in Chongqing, Deng (2017) found that many homeowners’ contact with other people decreased after they moved from work-unit compounds to gated communities. However, Douglass et al. (2012) argued that residential enclaves do not necessarily prevent contact across different social groups for three reasons. First, gates do not necessarily prevent people from accessing the neighbourhood. Second, amenities in gated communities are not provided exclusively for residents, as people living outside can also use the facilities or services. Finally, people in China are more accustomed to the use of gates to separate living and business environments. This is supported by Breitung (2012), a study that examines residents’ attitudes towards gated living environments, using interviews from residents living inside and outside three gated communities in Guangzhou. Those living inside the gates valued security and a good residential environment, whilst those living outside showed great acceptance or approval of using gates and walls. It seems that gating is not seen as a problem or a cause for social tensions in Chinese cities in contrast with Western contexts.

5.2 The Impacts on Job Opportunities and Wages

The literature has long suggested that migrants in Chinese cities have fewer employment opportunities and lower income than otherwise comparable natives. For example, migrants are not eligible to apply for certain jobs in the public sector and state-owned enterprises. Such labour market discrimination against migrants is especially pronounced for rural-to-urban migrants (Meng and Zhang 2001). However, the urban literature also suggests that residents living in enclaves may experience both spatial constraints and network spill-over effects in terms of job opportunities. Empirical studies have discussed spatial mismatch effects for ethnic minorities living in enclaves, i.e. mismatch between the locations of job opportunities and enclaves, as residents may have poor access to low-skilled jobs located beyond enclaves (Houston 2005). The spatial mismatch effects may lead to longer commutes and reduce labour market success. On the other hand, ethnic minorities concentrated in enclaves may develop strong social networks and share information about job opportunities. This might facilitate their job search and improve their job prospects.

Most studies on enclaves and labour market outcomes in Chinese cities focus on urban villages. Drawing on data from the 2009 survey in 12 cities in four regions in China, Zhu et al. (2017) examined job accessibility and commuting behaviour for rural migrants living in urban villages and formal urban neighbourhoods such as work-unit compounds, public housing and commercial property estates. They found that migrants living in urban villages had shorter commuting times and distances and better job accessibility. This can be partly explained by the network effects, i.e. migrants originating from the same province or county tend to concentrate in the same urban village and share information about job opportunities. The migrant community is also capable of creating jobs, though many of these are informal. The other explanation is that many urban villages are located near industrial zones and factories as the result of urban expansion. Their convenient location helps migrants to secure job opportunities nearby.

Zhu (2016) further examined employment opportunities and wages for rural migrants living in urban villages and formal urban neighbourhoods using the same dataset. The author found that rural migrant workers living in urban villages had better employment prospects and higher wages, facilitated by their social networks. This is supported by other studies on urban villages demonstrating that social networks and a vibrant informal economy help migrants adapt to urban life and develop careers in the city. In one example, based on the individual-level data of the 2010 census in Shanghai, Liu et al. (2019) found that migrant enclave residence is positively associated with employment outcomes for rural migrants. The effect is particularly evident among female migrant workers and those who live in locations with relatively low job densities. However, such a positive social network effect is not shared by urban migrants or urban natives. The authors explain that rural migrants, lacking higher levels of educational attainment, are more likely to rely on social networks to secure jobs.

Studies also indicated that migrants originating from Zhejiang province developed successful clothes businesses in urban villages in suburban Beijing (e.g. Ma and Xiang 1998). A recent study in Guangzhou discusses the entrepreneurial activities of migrants originating from Hebei Province and their thriving garment business in an urban village (Liu et al. 2015). Migrant entrepreneurs actively use urban space to create job opportunities and achieve economic advancement and social mobility. New migrants from the same place of origin obtain help from their fellow migrants and find jobs in the same garment industry. It is noted that most of these jobs are informal in nature. The authors do acknowledge that not all migrant enclaves can promote migrant-owned business and facilitate migrants’ career development. In addition to tightly knit social networks in the enclaves, resources linked with native places and externally oriented economic activities are crucial for the emergence of migrant entrepreneurs.

6 Conclusions and Discussions

During the centrally planned period initiated by Chairman Mao in 1949, Chinese cities were characterised by mixed neighbourhoods comprised of socially homogenous work units with no discernible patterns of segregation. Since the initiation of the economic reforms in 1978, cities have experienced enormous transformation and spatial divisions between different socioeconomic groups, driven by market-oriented housing, land reforms, rapid economic and spatial restructuring and massive rural-to-urban migration. While the elite can afford to live in affluent gated communities, the urban poor are clustered in dilapidated neighbourhoods and urban villages. With the deepening of the economic reforms and the continued process of urban transformation, the patterns of segregation in Chinese cities are likely to change rather than being static.

Various methods have been employed to measure the extent of segregation in Chinese cities. All studies agree that urban segregation based on socio-economic status has increased significantly since the start of the economic reforms. Chinese cities are beginning to resemble Western cities in that people of similar socio-economic status tend to concentrate in certain residential areas. However, it is difficult to compare the extent of segregation in Chinese cities with that of North American or European cities by using index-based measurements. This is because the spatial scales used in European studies are typically quite different to those in Chinese ones and we know that, even in the same city, segregation indices can give very different results for different spatial scales. Index-based measures of residential segregation are also likely to underestimate the true extent because social segregation may also occur in leisure and activity contexts as well as places of residence (see Chap. 2). Segregation may influence residents’ ability to access resources and opportunities. The impact of urban segregation on social contact and labour market outcomes are mixed in Chinese cities. While there is evidence of some negative consequences, evidence also exists to demonstrate that by living in enclaves migrants can actively develop social networks and achieve economic advancement and social mobility.

Residential segregation can be observed in cities across the world, of course, but there are particular features within a Chinese urban context. These features should be understood and interpreted within the particular Chinese historical, social, cultural and institutional background. Gated communities are an example of how a particular form of segregation can have a very different meaning and impact in China compared with American and European counterparts. This is because the gated communities in China have a communal historical precedent popularised during the Maoist era and so do not necessarily have the connotations of exclusivity and xenophobia associated with gated communities in the West. Moreover, some of the political and economic processes that lead to segregation are unique to China such as the impact of land reforms and the ongoing importance of rural migration, increased city-to-city population mobility and the hukou system in driving socioeconomic inequality and residential segregation. In this chapter, we have, therefore, attempted to highlight the role of cultural and institutional factors that have shaped the socio-spatial structures in Chinese cities. These factors are likely to continue influencing segregation in China, together with the increasingly important impact of market forces. The characteristics of continuing urban segregation in China mirror various social-spatial structural transformations within the country and warrant extensive investigation. It provides an important area for future research.

In the next five chapters, these drivers of change and their implications for inequality are discussed in more detail, particularly with respect to urbanisation, migration and the anti-poverty programme (Chap. 5), the development and redevelopment of urban villages (Chap. 6) and Shanty towns (Chap. 7), inequalities in public services (Chap. 8) and the housing issues facing rural migrants (Chap. 9).

References

Atkinson R, Flint J (2004) Fortress UK? Gated communities, the spatial revolt of the elites and time-space trajectories of segregation. Hous Stud 19:875–892

Bian Y, Zhang Z (2002) Marketization and income distribution in urban China, 1988 and 1995. Res Soc Strat Mobil 19:377–415

Bray D (2005) Social space and governance in urban China: The danwei system from origins to reform. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA

Breitung W (2012) Enclave urbanism in China: attitudes towards gated communities in Guangzhou. Urban Geogr 33(2):278–294

Chan KW (2009) The Chinese hukou system at 50. Eurasian Geogr Econ 50:197–221

Chen J, Han X (2014) The evolution of housing market and its socio-economic impacts in post-reform China: a survey of the literature. J Econ Surv 28(4):652–670

Chen Z, Yeh A (2019) Accessibility inequality and income disparity in urban China: a case study of Guangzhou. Ann Am Assoc Geogr 109:121–141

Deng F (2017) Gated community and residential segregation in urban China. GeoJournal 82:231–246

Douglass M, Wissink B, Van Kempen R (2012) Enclave urbanism in China: consequences and interpretations. Urban Geogr 33(2):167–182

Du H, Li S, Hao P (2018) ‘Anyway, you are an outsider’: temporary migrants in urban China. Urban Stud 55(14):3185–3201

Duncan O, Duncan B (1955) A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. Am Sociol Rev 20:210–217

Fang Y (2006) Residential satisfaction, moving intention and moving behaviours: a study of redeveloped neighbourhoods in inner-city Beijing. Hous Stud 21(5):671–694

Forrest R, Yip N (2007) Neighbourhood and neighbouring in contemporary Guangzhou. J Contemp China 16(50):47–64

Granovetter M (1983) The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. Sociol Theory: 201–233

Hao P (2015) The effects of residential patterns and Chengzhongcun housing on segregation in Shenzhen. Eurasian Geogr Econ 56:308–330

He S (2010) New-build gentrification in central Shanghai: demographic changes and socioeconomic implications. Popul Space Place 16(5):345–361

Houston D (2005) Methods to test the spatial mismatch hypothesis. Econ Geogr 81:407–434

Huang Y (2004) The road to homeownership: a longitudinal analysis of tenure transition in urban China (1949–94). Int J Urban Reg Res 28(4):774–795

Huang Y (2012) Low-income housing in Chinese cities: policies and practices. China Q 212:941–964

Huang Y, Yi C (2009) Hukou, mobility, and residential differentiation: a case study of Wuhan. Urban Stud 16(6):36–46

Kaplan D, Holloway S (2001) Scaling ethnic segregation: causal processes and contingent outcomes in Chinese residential patterns. GeoJournal 53(1):59–70

Kirkby R (1985) Urbanization in China: Town and country in a development economy 1949–2000 AD. Croom Helm Ltd., London

Li S, Huang Y (2006) Urban housing in China: market transition, housing mobility and neighborhood change. Hous Stud 21(5):613–623

Li Z, Wu F (2008) Tenure-based residential segregation in post-reform Chinese cities: a case study of Shanghai. Trans Inst Br Geogr 33:404–419

Lin S, Gaubatz P (2017) Socio-spatial segregation in China and life experiences: the case of Wenzhou. Urban Geogr 38(7):1019–1038

Liu C, Chen J, Li H (2019) Linking migrant enclave residence to employment in urban China: the case of Shanghai. J Urban Aff 41(2):189–205

Liu L, Huang Y, Zhang W (2018a) Residential segregation and perceptions of social integration in Shanghai, China. Urban Stud 55(7):1484–1503

Liu L, Silva E, Long Y (2018b) Block-level changes in the socio-spatial landscape in Beijing: trends and processes. Urban Stud. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018757617

Liu R, Wong T (2015) The allocation and misallocation of economic housing in Beijing: target groups versus market forces. Habitat Int 49:303–315

Liu Y, Li Z, Liu Y, Chen H (2015) Growth of rural migrant enclaves in Guangzhou, China: agency, everyday practice and social mobility. Urban Stud 52:3086–3105

Lo C (1994) Economic reforms and socialist city structure: a case study of Guangzhou, China. Urban Geogr 15:128–149

Logan J, Fang Y, Zhang Z (2009) Access to housing in urban China. Int J Urban Reg Res 33:914–935

Ma L, Xiang B (1998) Native place, migration and the emergence of peasant enclaves in Beijing. China Q 155:546–581

Madrazo B, Van Kempen R (2012) Explaining divided cities in China. Geoforum 43:158–168

Manley D, Kelvyn J, Ron J (2019) Multiscale segregation: multilevel modeling of dissimilarity—challenging the stylized fact that segregation is greater the finer the spatial scale. Prof Geogr 71(3):566–578

Meng X, Zhang J (2001) The two-tier labor market in urban China: occupational segregation and wage differentials between urban residents and rural migrants in Shanghai. J Comp Econ 29(3):485–504

NSB National Statistical Bureau (2016) Information on the 2015 National 1% Population Sample Survey Data. Available at https://www.unicef.cn/figure-14-percentage-ethnic-minority-groups-province-2015. Accessed 25 Oct 2019

Shen J, Xiao Y (2019) Emerging divided cities in China: socioeconomic segregation in Shanghai, 2000–2010. Urban Stud. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098019834233

Sun C, Lin T, Zhao Y, Lin M, Yu Z (2017) Residential spatial differentiation based on urban housing types—An empirical study of Xiamen island, China. Sustainability 9:1-17

Tan Y, Kwan M, Chai Y (2017) Examining the impacts of ethnicity on space-time behavior: evidence from the City of Xining, China. Cities 64:26–36

Van Kempen R, Murie A (2009) The new divided city: changing patterns in European cities. Tijdschr Voor Econ En Soc Geogr 100:377–398

Van Kempen R , Van Weesep J (1998) Ethnic residential patterns in Dutch cities: backgrounds, shifts and consequences. Urban Stud. 35:1813–1833

Wang D, Li F, Chai Y (2012) Activity spaces and sociospatial segregation in Beijing. Urban Geography 33(2):256–277

Wang Y (2000) Housing reform and its impacts on urban poor in China. Housing Studies 15(6):845–864

Wang Y, Murie A (1999) Housing policy and practice in China. St. Martin’s Press, New York

Wang Z, Zhang F, Wu F (2016) Intergroup neighbouring in urban China: Implications for the social integration of migrants. Urban Studies 53:651–668

Wang Z, Zhang F, Wu F (2017) Neighbourhood cohesion under the influx of migrants in Shanghai. Environment and Planning A 49(2):407–425

Wu F (2005) Rediscovering the ‘gate’ under market transition: From work-unit compounds to commodity housing enclaves. Housing Studies 20(2):235–254

Wu F, Li Z (2005) Sociospatial differentiation: Processes and spaces in subdistricts of Shanghai. Urban Geography 26:137–166

Wu F, Zhang F, Webster C (2013) Informality and the development and demolition of urban villages in the Chinese peri-urban area. Urban Studies 50:1919–1934

Wu Q, Cheng J, Chen G (2014) Sociospatial differentiation and residential segregation in the Chinese city based on the 2000 community-level census data: A case study of the inner city of Nanjing. Cities 39:109–119

Wu W (2002) Migrant housing in urban China: Choices and constraints. Urban Affairs Review 38(1):90–119

Zhao M, Wang Y (2018) Measuring segregation between rural migrants and local residents in urban China: An integrated spatio-social network analysis of Kecun in Guangzhou. Environment and Planning b: Urban Analytics and City Science 45(3):417–433

Zhao P (2013) The impact of urban sprawl on social segregation in Beijing and a limited role for spatial planning. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 104(5):571–587

Zhou S, Deng L, Kwan M, Yan R (2015) Social and spatial differentiation of high and low income groups’ out-of-home activities in Guangzhou, China. Cities 45:81–90

Zhu P (2016) Residential segregation and employment outcomes of rural migrant workers in China. Urban Studies 53:1635–1656

Zhu P, Zhao S, Wang L, Yammahi S (2017) Residential segregation and commuting patterns of migrant workers in China. Transp Res Part D 52:586–599

Zou J, Chen Y, Chen J (2020) The complex relationship between neighbourhood types and migrants’ socio-economic integration: The case of urban China. J Housing Built Environ 35(1):65–92

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the financial supports from the NSFC-ESRC Joint Funding (NSF71661137004) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC71974125; NSF71573166).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chen, Y., Chen, J. (2021). Research on Residential Segregation in Chinese Cities. In: Pryce, G., Wang, Y.P., Chen, Y., Shan, J., Wei, H. (eds) Urban Inequality and Segregation in Europe and China. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74544-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74544-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-74543-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74544-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)