Abstract

Socio-economic residential segregation is a common feature of almost all Argentinean cities, neatly divided into poor, middle-class, and affluent neighborhoods. At the end of the 1980s, and especially over the 1990s, the process of suburbanization for affluent and upper middle-class groups was consolidated as a generalized model. This study concentrates on the trends and the patterns of socio-economic segregation in Buenos Aires and focuses on two major dimensions of segregation: the spatial concentration patterns of a given social group in specific areas and the degree of social homogeneity within such areas. Socio-economic segregation is described using the highest level of education that a householder has completed as a proxy for socio-economic status. The indices of segregation and dissimilarity are used as the main measure to compare the level and changes of residential segregation but other metrics—such as location quotient index—are also used to estimate the degree of homogeneity or heterogeneity in neighboring areas. This study uses population and household census data from 1991, 2001, and 2010 provided by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC), and the data are presented at the spatial disaggregation level of block groups called ‘radios censales’.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Residential segregation accounts for the degree of inequality acquired by the spatial distribution of the population. Over the last decades, social sciences have shown renewed interest in the study of this phenomenon in the United States and in Europe as well as in Latin America. Although these studies share the objective of evaluating the magnitude and effects of certain spatially concentrated population groups on people’s living conditions, they differ in relation to the criteria used for social differentiation. While in the United States and Europe, the research was, to a large extent, focused on racial and ethnic segregation and migration, in Latin America the analyses that focus on territorial relations among socio-economic groups were favored (Groisman 2009; Molinatti 2013; Sabatini 2006).

In the latter group of countries, the emphasis on the socio-economic dimension of residential segregation is understandable considering that the rigidity of the social structure and substantial social, income, and class inequalities represent perhaps the most outstanding characteristics of the social structure of Latin American countries (Groisman 2010; Sabatini 2006). In this context, the functioning of labor markets is a key element to understand the fluctuations in the well-being of the vulnerable populations, mainly because, due to the absence of generalized credit markets, lower social classes’ homes obtain most of their income from the labor insertion of their members, usually in unsteady and low-paid jobs (Groisman 2009).

The interrelationship between the social structure and the urban spatial structure is multifaceted. Residential segregation takes place when the existing inequalities of a community are made visible in a territorial or geographical manner. However, residential segregation is not a simple reflection of social reality, since space is considered a dimension that composes the processes that structure social reality. Likewise, there are other intermediate processes or mechanisms that encourage segregation or counteract its outcomes, including, among others, land markets, housing policy, and the labor market (Molinatti 2013; Sabatini 2006; Torres et al. 2003).

Since the end of the twentieth century, Latin America has witnessed a proliferation of theoretical investigations and, to a greater extent, empirical research related to residential segregation, especially in large metropolises of the most urbanized countries in the region. The emergence of this line of research is linked to the processes of impoverishment of Latin American societies during the 1990s pertaining to the implementation of the neoliberal development model. The opening of the regional economies, in conjunction with policies aimed at reducing state intervention in the economy, caused a rapid increase in unemployment and a resulting decrease in the income of households belonging to lower social class.

Other phenomena also influenced the revitalization of residential segregation studies in the region. In particular, an increase in the concentration of elites and the affluent middle classes was a process reflected in the proliferation of gated communities and in the resulting suburbanization of these social groups (Caldeira 2007; Svampa 2004; Torres 2001). Both phenomena led to the reorganization of the Latin American cities, mainly represented

…. as the displacement of an “open city” model, basically European, focused on the notion of public space and on values, such as political citizenship and social integration, towards a “closed city” regime, more associated with the North American type, marked by the affirmation of patrimonial citizenship centered on the figure of the taxpayer (Svampa 2004: 16).

The impact of these changes on socio-economic residential segregation shows opposite trends in Latin American cities. A trend would indicate a reduction in the level of residential segregation as a result of the relative dispersion of closed condominiums, shopping centers, offices, and services located outside the city center and the high-income area leading to physical proximity between popular and elite groups. As signaled by various authors, it is important to mention that this greater physical proximity does not produce social integration or mixture per se. Another trend, however, corresponds to the increase in the level of segregation of new groups of lower class housing that have access—by formal or informal means—to urban lands located far away from the city, as a result of real estate speculation and its impact on land prices (Sabatini 2006).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, there was a positive growth in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Latin American economies, although there remained variations in social indicators. In the regional context, Argentina is a particular example as this change took place dramatically. After the great economic crisis of 2001–2002 (when the GDP shrank significantly and poverty spread to more than 50% of the population), the Argentinian economy had seven years of sustained GDP growth at average annual rates of 8–9% (Groisman 2009). In 2009, despite the international economic crisis, the country registered an annual GDP variation rate of 0.9% above the average of the region that showed −1.8% (ECLAC 2010). After that crisis, Argentina returned to a vigorous growth rate with average annual increases of 7–9% between 2010 and 2011.

In this context, it is necessary to investigate how social inequalities and socio-economic residential segregation indicators evolved in Greater Buenos Aires, the main urban agglomeration of the country, and whether these political, social, and economic transformations produced consistent changes in the spatial distribution of the population.

2 The Functioning of the Labor Market and the Concentration of Income

At the beginning of the 1970s, the Argentinean labor market was characterized by being relatively integrated, with a high presence of salaried work and low levels of underemployment. However, as a consequence of the poor macroeconomic performance experienced by the Argentinean economy during the mid-1970s and early 1990s, this trend was overturned and the period was marked by stagnation and instability (Altimir and Beccaria 1999, Arceo et al. 2008).

Labor regulations were key elements in the structural reforms of the so-called “neoliberal decade” (1989–2001).Footnote 1 These measures were aimed at the convenience of adapting legislation concerning individual and collective relations in order to provide more flexibility and, basically, to reduce non-wage labor costs (social security contributions and costs related to events, such as dismissal or accidents, or making the distribution of work time more flexible and the decentralization of negotiation) (Altimir and Beccaria 1999; Arceo et al. 2008).

Flexibility in the labor market, combined with the process of foreign trade opening for foreign trade in the context of an increasingly overvalued exchange rate that led to a significant loss of competitiveness in the goods and services production areas, resulted in a significant reduction in workforce demand, a rise in unemployment, and it created instability, insecurity, and low productivity. This phenomenon, typical of the informal side of the economy, caused a progressive gap between workers with lower qualifications and those with higher ones (Arceo et al. 2008). One of the most severe consequences of the subsequent changes introduced in labor legislation during this period was job insecurity, characterized by an increase in time-related underemployment and unreported employment, which, together with unemployment and wage stagnation, negatively affected the living conditions of the population. The profound economic recession that the Argentinean economy suffered between 1998 and 2002 significantly worsened the current problems in the local labor market, resulting in the great economic and political crisis at the end of 2001 and 2002, which caused a shrinking of approximately 20% of the GDP (Basualdo 2008).

After this great economic crisis, there was a change in the macroeconomic system that led to a period of sustained and long-lasting economic recovery between 2003 and 2006. This period was characterized by a strong increase in employment and purchasing power, an increase in the number of registered workers, and a decrease in unemployment and time-related underemployment (Arceo et al. 2008). Likewise, there was a substantial reduction in absolute poverty even though some authors claim that at the level of redistribution, the evolution was not so satisfactory (Groisman 2010). Although income distribution has a tendency to reduce in concentration, the distribution of wealth remained highly unequal (Báez 2017).

This process of expansion and growth was fuelled by an increase in payroll as a result of a decrease in the unemployment rate (from 16.3% in the third quarter of 2003 to 7.5% in the third quarter of 2010), the increase in the average real wage of 35% between 2003 and 2010, the increase in the adjustable minimum living wage, the increase in minimum retirement benefits, and so on.Footnote 2 This was also due to the implementation of new social policies: the incorporation of three million people into the Social Security System through the Provisional Inclusion Plan (2004–2007), the execution of the Universal Child Allowance (Asignación Universal por hijo, AUH) in October 2009, among others (For further information about new social policies applied, consult Alonso and Di Costa 2012).

Regarding income distribution,Footnote 3 during the so-called “neoliberal decade,” there was a deepening of income inequality and regressive income distribution. Between 1991 and 2002, the Gini index rose from 0.468 to 0.538. The reversal of this trend started in 2002/2003 when the former President Néstor Kirchner took office, with a Gini index decreasing to 0.507 by 2003. From this moment on, there is an unquestionable reduction in income inequality—the index decreased to 0.483 in 2004 and further to 0.410 in 2013. However, some authors show that the slight improvement in equity at the beginning of the expansive phase diminished from 2004 (e.g., Groisman 2010). At the same time, a view of greater global scope shows that this relative improvement is significantly worse during most of the 1980s when the index fluctuated around 0.400.

3 Characterization of Greater Buenos Aires

Greater Buenos Aires (Gran Buenos Aires, GBA)Footnote 4 is the main urban agglomeration of Argentina and the most important economic and industrial center of the republic. This agglomeration constitutes an urban entity both from the functional point of view—since it is an area that many people commute to for work on a daily basis—and from the physical point of view—an urban sprawl (“mancha urbana”) without any important solutions for continuity.

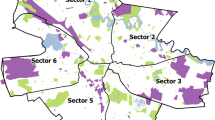

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, INDEC) of 2003, this agglomeration is formed by the City of Buenos Aires (central area and federal capital city of the Argentine Republic) together with a group of 24 municipalities, also called “partidos”—of the Province of Buenos Aires. The 24 municipalities formed the first and second regions of the Buenos Aires Conurbation (Conurbano Bonaerense). Whereas the first one is a semi-circular crown that extends up to approximately 25 km from the center and involves those municipalities adjacent to the capital, the second one is a subsequent semi-circular crown that extends up to 40 or 50 km from the center (Fig. 23.1).

Source Based on INDEC 2003 and http://mapas-lsig.ungs.edu.ar/visor/map.phtml

Geography of greater Buenos Aires.

Buenos Aires, compared with other Latin American metropolises, displays an extended process of metropolization and had earlier access to a process of industrialization. Though, paradoxically, it least resembles the ideal ‘industrial’ model according to the tendency of the high socio-economic strata to move from the center to the suburbs, while the lower strata increasingly occupy the central area abandoned by the ‘elite.’ In this regard, the density structure in Buenos Aires did not advance regularly from condensed to scattered forms accompanying the technological development of transport, urban growth, and economic development, as proposed by Clark (1977). On the contrary, the alternation between the periods of concentration and dispersion are not only accounted for by transport technology (the transition from tram to public transport) but also by the organization and funding of the transport system as a factor in the creation of the urban space (Torres 1975). These specifications have resulted in a complex territory, highly influenced by a tendency toward fragmentation and polarization. This can be summarized as follows:

-

The process of suburbanization during the period of 1940–1960 took place earlier and was much more significant in comparison with other Latin American metropolises. This displacement of the population was motivated by the sale of parcels of land in the urban periphery and by large subsidies that radically reduced the costs of suburban transportation, which facilitated daily commuting.

-

The suburbanization of groups with higher incomes—the elite—took place with high intensity in the 1990s in Buenos Aires, but at a slower pace in comparison with American and many of the Latin American metropolises. The new real estate developments respond to the type of gated community and are inserted into the urban fabric establishing a clear contrast with the open ones that characterized the early development of Buenos Aires metropolitan area.

-

The polarization of the main urban center—the City of Buenos Aires—during the 1990s was characterized by a significant increase in construction activity in the conventional market directed mainly toward the luxury homes and by a considerable increase in the number of people living in shantytowns (“villas miserias”). Likewise, the central area remained pre-eminent in the City of Buenos Aires regarding its political and administrative functions as well as the location of higher, middle and upper classes, despite the process of deterioration that took place in central regions during the 1980s. Since the 1990s, the local government of Buenos Aires has been promoting an intense process of urban transformation in the central area and the neighborhoods in the Southeast (Puerto Madero, La Boca, Barracas, Parque Patricios, and Nueva Pompeya). However, gentrification processes took place to a very limited extent and its impact has been marginal due to the fragmentation of the urban structure, the weight of negative environmental factors, as well as the presence of a high proportion of low-income populations (Di Virgilio and Guevara 2014; Suárez 2011; Torres 2001).

4 Data Collection and Methods

4.1 Data Collection and Study Period

The sources used were the census micro databases from the 1991, 2001, and 2010 population and housing censuses available in Redatam format (INDEC 1991, 2001, 2010). These census data provide representative estimates for small geographical areas. The spatial units chosen for segregation analysis were block groups called ‘radios censales’, the smallest geographical area available to the public (c. 300 dwellings and around 800 people per unit on average, regardless of its geographic size).

To analyze the patterns of socio-economic segregation in Greater Buenos Aires, we used an educational attainment indicatorFootnote 5: the highest level of education that a household memberFootnote 6 has completed. Four categories are distinguished from each other:

-

Low educational level (lower than primary education, including people who never attended an education program),

-

Middle-low educational level (completed primary education, including people with some secondary education),

-

Middle-high educational level (completed secondary education, including people with some tertiary or university education), and

-

High educational level (completed tertiary or university education).

Between 1991 and 2010, in the City of Buenos Aires as well as in Buenos Aires conurbation, a substantial improvement was observed in the educational profile of households. The relative weight of the categories that put together the householders with low education with those who did not finish secondary school diminished significantly in the period analyzed (from 67.1% in 1991 to 49.0% in 2010); although the absolute increase in the middle-low group stood out during the years 2001–2010.Footnote 7 Consequently, there was an increase in the absolute and relative presence of householders with complete secondary education or more, especially, among those who had access to higher education and completed their studies, the absolute number doubled between 1991 and 2010, and its relative participation rose from 11 to 19% during the same period (Fig. 23.2).

This apparent improvement in educational level is a phenomenon that can respond to different factors, and it should not be automatically understood as the upward social mobility of householders that improved their education. Rather, it is likely to respond to other factors, such as the generational change due to the constitution of new homes with householders younger and better educated than their parents and grandparents, and help by the progressive democratization of access to secondary school, despite the substantial social inequalities that still prevail.

4.2 Data Analyses

This study consists of two stages. In the first stage, we use the traditional indicators of segregation to compare levels and changes of socio-economic segregation. We calculate indices of segregation (IS) and dissimilarity (D) for all four educational categories of householders. Given that socio-economic segregation is usually lower than ethnic and racial segregation, we interpret values below 20 and above 40 as low and high, respectively (Tammaru et al. 2016).

In the second stage, we investigate the patterns and local geographies of socio-economic residential intermixing, using:

-

Local segregation indices, specifically the Location Quotient (LQ). The LQ is a ratio between the share of a given group in a given spatial unit and the city-wide share of this group. If the ratio is less than 1, the group is underrepresented in the given neighborhood, and if it is more than 1, the group is overrepresented in the given neighborhood. We use LQ maps for the highest and lowest educational attainment categories to visualize the relative spatial concentration or dispersion of educational groups in the neighborhoods of the city.

-

Classification of neighborhoods, in this paper ‘radios censales’, based on the socio-economic composition of residents. Having divided the householders into three general educational categories (higher, middle, and lower educational groups), we merge different threshold combinations to capture the socio-economic status (SES) of the neighborhoods. Consequently, we distinguish seven types of socio-economic intermixing, based on Marcińczak et al. (2015): high SES neighborhoods, high to middle SES neighborhoods, mixed neighborhoods, middle SES neighborhoods, low to middle SES neighborhoods, and low SES neighborhoods. The typology is then illustrated in choropleth maps to revel the local geography of socio-economic intermixing in GBA.

-

Location of the top socio-economic status groups, based on the distribution of householders with a high educational level in ‘radios censales’ by quintiles. The spatial units in the first quintile (Q1) will be the spatial units that house 20% of householders with the best educational levels in GBA.

5 Results

5.1 Socio-Economic Segregation According to Global Indices

According to Musterd et al. (2015), previous studies on socio-economic residential segregation in the United States of America and European countries reveal that higher socio-economic groups are generally more segregated than lower socio-economic ones. Such patterns have also been found in cities of Latin America (Agostini et al. 2016; Becceneri et al. 2019; Molinatti 2013; Sabatini et al. 2009, among others). The results for Greater Buenos Aires are presented in Tables 23.1 and 23.2 and support these findings. Householders with a high education level are the ones who are more segregated than householders with a lower educational level, with IS above 50% in the last three years analyzed. The least segregated, by contrast, correspond with the group of householders with middle-high education with values that can be interpreted as intermediate (Tables 23.1 and 23.2).

If we analyze the variations between 1991 and 2010, taking into account the economic fluctuations that occurred during the period analyzed, it can be observed that the levels of socio-economic residential segregation showed a little variation for the extreme socio-economic groups, defined according to the highest educational level attained. For the intermediate groups, which include slightly more than 70% of householders, there are clear trends although segregation levels can be interpreted as intermediate in the 3 years of census data. Whereas the lower middle class raised its segregation level by 50%, reaching values close to 40 by 2010, the segregation in the higher middle class diminished from 36 in 1991 to 25 in 2010Footnote 8 (Table 23.1).

Given the strong increase in the educational level of household heads between 1991 and 2001, the small decrease in the indices of educational segregation are indicative of the persistence of segregation. However, as Tammaru et al. (2019) showed for eight European urban areas, the relationship between inequality and spatial segregation can lag and changes in inequality can take, for example, 10 years to produce different levels of residential segregation between educational groups.

Regarding the degree of residential segregation among the social categories analyzed, especially between the opposite ends of the social hierarchy, the D between the groups shows a narrow correlation between the educational level of the householders and their residential localization, suggesting a high correspondence between the spatial distribution of the groups and the present education gap between them. The index reaches lower values when it is calculated between contiguous educational groups and higher values between the opposite ends (Table 23.2).

Among the variations observed between 1991 and 2010, it can be highlighted, on the one hand, the high values of residential segregation between low and high educated householders with D over 70, despite a minor setback during the period analyzed. On the other hand, the increase in residential segregation of the heads of household with higher education in relation to those with medium-low education and, especially, medium-high education. For example, among the social categories with greater educational achievements, the index increased almost 15 percentage points, signaling a progressive differentiation in the residential localization of the educational elites (those householders that completed higher education) in relation to those that only finished compulsory education (Table 23.2).

5.2 Changing Local Patterns of Segregation

In the previous section, it was established, in a general way, that the most concentrated and segregated educational group in relation to the remaining groups was the one composed of the most educated householders (complete higher education), followed by the group of householders with lower educational level. In order to analyze the local patterns of segregation, we used LQ maps, which show how concentrated a specific group is in a particular area in comparison to the concentration in the city as a whole.

Figure 23.3 shows that the concentration of educational elites is higher in the City of Buenos Aires, mainly in the spatial units located in the communities of the center and the north, and in the northern localities of Buenos Aires conurbation (San Isidro and Vicente López). Additionally, the householders with a low educational level are concentrated mostly in the periphery of GBA—forming a ring—especially in the localities of GBA not adjacent to the capital city, which belong to the second crown of Buenos Aires conurbation (Florencio Varela at the south-east and José C. Paz, Malvinas Argentinas, Merlo, Moreno and San Miguel at the northwest and west).

Between the period between 1991 and 2001, this pattern of territorial organization remains, generally speaking, but it has an in-depth increment of urban fragmentation and residential polarization. On the one hand, the householders who belong to the educational elite are over-represented and growing over time in the central and northern regions of the City of Buenos Aires (high-rise buildings of very good quality). Similarly, in the districts of San Isidro and Vicente López (both with very high average purchasing power and characterized by a large percentage of permanent housing in gated communities, and particularly, in Vicente López with high-rise condominiums with amenities, due to its proximity to the capital city). On the other hand, the least educated householders keep concentrating in the periphery of GBA, which highlights a growing over-representation in time of this group in the locality of La Matanza.Footnote 9

The typology of the ‘radios censales’ based on the SES revealed additional information about the local patterns of socio-economic mixture (Fig. 23.4), among which it stands out that

-

Most “radio censales” fall under the Middle category and, in the three census years, above 55%.

-

There is a greater absolute and relative presence of ‘radios censales’ classified into the higher categories of SES over time. Whereas, in 1991, about two out of every ten spatial units corresponded to residential spaces with a high concentration of householders with high educational level and low presence of householders with low educational level, in 2010 that relation increased to about four out of ten.

-

An absolute and relative decrease in ‘radios censales’ classified as low-middle, mainly between the census of 2001 and 2010, since their reclassification in middle.

-

The absence of polarized ‘radios censales ’probably occurred due to the traditional high presence of middle segments in Argentinean society and to the increase in the universalization of middle education.

Figure 23.5 shows the localization of the socio-economic group situated in the upper end of the social scale; for example, householders with a high educational level. Between 1991 and 2010, there was a spatial deconcentration of this group, which coincides with a trend of constant growth, the suburbanization of the elites. The first quintile of the distribution expands from the center of the City of Buenos Aires to the North and toward the northern localities of GBA—areas that have the best services, qualified workforce, fastest communication speed, and better resources, in general. For example, during the 1990s, in that area, three-quarters of all building developers in Buenos Aires were located here, as was almost all new business centers and the international hotel industry, two-thirds of the industrial investment and highway construction network, and more than half of the shopping centers and hypermarkets (Marcos 2009).

6 Discussion and Conclusions

Buenos Aires is complex in many ways, with its jurisdictional complexity being a characteristic that pushes the current trends toward urban fragmentation and residential polarization. GBA’s current structure crystallizes the historical north/south and center/periphery contrasts. Moreover, new contrasts are added which delimit full and inclusive access to the city for a part of its population (Marcos and Mera 2018).

During the study period, there were important structural economic changes in Argentina (Groisman 2010; Marcos 2009; Suárez 2011; Torres 2001). On the one hand, the establishment of an open accumulation model, which, although it was implemented from the mid-1970s onward, the most drastic transformations occurred in the 1990s—particularly the subsequent amendments in labor legislation aiming at a higher labor flexibilization. On the other hand, after the great crisis of 2001, there was a change in the macroeconomic regime that gave rise to a period of sustained and long-lasting economic recovery. Simultaneously, there were changes in the way of planning and management of the city, which can be summarized in a transference of the management of urban development to private capital, and in the resulting residential polarization.

The aim of this study was to investigate how the indicators related to socio-economic residential segregation developed in a context characterized by major social, economic, and political transformations. These results confirm some tendencies probed by other researches in the process of urban spatial structuring and residential segregation in GBA (Groisman 2010; Rodriguez 2016; Suárez 2011; Torres 2001). First, the main trend of the 1990s was the residential polarization in the City of Buenos Aires as well as in the conurbation, where the group of a greater socio-economic level was the most significant actors of that period regarding the definition of social spaces. Second, the process of suburbanization of the elites intensified; it was a process that was parallel to the increase in closed urbanization (at the beginning of the 1990s, there were around 90 undertakings and by 2007 there were nearly 550). At the same time, there is a rise of precarious settlements, combined with the generalized deterioration in traditional neighborhoods where people from lower and middle classes lived. Third, the sustained growth of the economy after the great economic crisis of 2001 would not have had a sharp effect on the reduction of segregation, for two main reasons: on the one hand, the values of the indices are still high, especially, between the two opposite ends of the social scale, and on the other hand, because local patterns were not substantially modified and in some areas of GBA, residential polarization increased.

During the first period, 1991–2001, the growth—or the persistence of high levels—of residential segregation, especially between the opposite ends of the social scale, was the result of an ongoing trend of job insecurity and social exclusion of certain individuals, despite significant increases in the educational levels of the population. During the second period, 2001–2010, the educational improvement of the population continued, but in a context of economic recovery and equity improvement. Evidence suggests that economic growth would not have had a profound effect as the ones observed in labor indicators, especially during the first period of the expansive phase (2002–2004) on socio-economic residential segregation. The levels of residential segregation remain high and continue to assert themselves through new forms of spatial separation, such as through gated communities. The arrival of elites in traditionally popular residential areas would seem to reflect greater social heterogeneity of the conurbation and a reduction in residential segregation. However, the characteristics of new neighborhoods intensify residential segregation on a reduced geographical scale. Private fences, walls, and security checkpoints guarantee the isolation of elites from the surrounding poor areas and split the territory.

All these characteristics highlight a trend toward an extremely segregated and divided city, and the determination of the processes of territorial fragmentation and residential polarization, in spite of substantial improvements in the educational attainment of the population and the period of sustained economic growth that GBA and a great number of Latin American countries went through at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The results of this study confirm the findings of other research that account for the great force of the processes of urban space development. Therefore, it must be emphasized the need for active public policies that promote social diversity space and full and inclusive access to the city, dismantling the areas of residential and socio-occupational marginalization that deteriorate the conditions for urban integration and reproduce concentrated poverty.

Notes

- 1.

This “neoliberal decade” comprises two governments: the one of Carlos Saúl Menem (1989–1999) and the one of Fernando de la Rúa (1999-2001). The latter resigned in the context of the major Argentinean crisis at the end of 2001.

- 2.

The main changes in labor legislation between 2003 and 2007 can be consulted in: Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Argentino (2007).

- 3.

Values corresponding to the estimates conducted by: World Bank, Development Research Group (2019).

- 4.

According to the latest National Census of Population and Housing (2010), Greater Buenos Aires has 12,806,886 inhabitants, of whom 2,890,151 people live within the border of the City of Buenos Aires. While the population of the main urban area decreased to an annual rate of 0.14% during the period analyzed (between 1991 and 2010), the population of Buenos Aires conurbation increased to an average annual rate of 1.16%.

- 5.

No data available on the occupational structure for smaller geographic areas for the censuses of 1991 and 2010. We used as a proxy variable the highest level of completed education under the assumption that there is a strong correlation between the education of the householders, the occupation, and the probability of obtaining higher income and a better quality of life in general. Detailed information about the relationship between income, education, and occupation can be found in Tammaru et al. (2016).

- 6.

In order to avoid a distorting effect of the age structure on the education of a population, and trying to capture a special group of influence, we worked with householders of 30–59 years old.

- 7.

Between 1991 and 2001, the absolute number of householders with middle-low educational level decreased by just over 58 thousand people. However, between 2001 and 2010, that same group increased by little more than 56 thousand people, showing between 1991 and 2010 a decrease of 1.800 people in the number of householders with middle-low educational level.

- 8.

However, these indices can be affected by the difference in the number of minorities in the total population. In the period analyzed, the lower middle class diminished 11 percentage points in size and the higher middle group increased 10 percentage points. These variations can be linked to significant improvements in the educational level in the Argentinean population due to the increased schooling in the middle level during the 1990s.

- 9.

La Matanza is a locality of the first cordon of Buenos Aires conurbation—although due to its extension, it is divided between the two of them—that experienced, in conjunction with José C. Paz, Moreno and Florencio Varela, the greatest demographic growth between 1991 and 2001. Moreover, in the same period the number of the population in shantytowns and settlements tripled. This trend continues growing until 2010, and as a consequence of the growing difficulties of the popular areas to access urban land, there is a huge densification of the current shantytowns and settlements (Cravino, Del Río and Duarte 2008). This locality, as well as most of the other ones belonging to the second cordon, presents significant deficits in infrastructure and urban and domiciliary services at the beginning and end of the period analyzed.

References

Agostini CA, Hojman D, Román A, Valenzuela L (2016) Segregación residencial de ingresos en el Gran Santiago, 1992-2002: una estimación robusta. EURE 42(127):159–184. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612016000300007

Alonso G, Di Costa V (2012) Cambios y continuidades en la política social argentina (2003–2010). Working papers. Grupo de Investigación en Gobierno, Administración y Políticas Públicas. Instituto Universitario de Investigación Ortega y Gasset. Madrid

Altimir O, Beccaria L (1999) El mercado de trabajo bajo el nuevo régimen económico en Argentina. Working Paper. Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL). http://www.eclac.cl/publicaciones/xml/0/4550/lcl1217e.pdf

Arceo N, Monsalvo A, Schorr M, Wainer A (2008) Empleo y salarios en la Argentina. Una visión de largo plazo. Capital Intelectual, Buenos Aires

Báez J (2017). Distribución de ingresos y riqueza en Argentina. Resource document. http://cdes.org.ec/web/distribucion-en-argentina/

Basualdo EM (2008) La distribución del ingreso en la Argentina y sus condicionantes estructurales. Centro de Estudios Legales y Sociales (CELS), Derechos Humanos en Argentina: informe 2008. Buenos Aires, Siglo XXI Editores Argentina, pp 307–326

Becceneri L, Alves H, Vazquez D (2019) Estratificação Sócio-Ocupacional e Segregação Espacial na Metrópole de São Paulo nos Anos 2000. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais 21(1):137. http://dx.doi.org/10.22296/2317-1529.2019v21n1p137

Caldeira TP (2007) Ciudad de muros. Gedisa, Barcelona

Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Argentino (2007). El trabajo en Argentina. Condiciones y perspectivas. Informe trimestral. https://www.adum.org.ar/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/cenda-el-trabajo-en-argentina.pdf

Clark C (1977) Population growth and land use. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Cravino MC, del Río JP, Duarte JI (2008) Magnitud y crecimiento de las villas y asentamientos en el Área Metropolitana de Buenos Aires en los últimos 25 años. Conference procceding. XIV Encuentro de la Red Universitaria Latinoamericana de Cátedras de Vivienda-Facultad de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Diseño-Universidad de Buenos Aires. http://www.igc.org.ar/megaciudad/N3/Asentamientos%20Irregulares%20AMB.pdf

Di Virgilio M, Guevara T (2014) Gentrificación liderada por el Estado y empresarialismo urbano en la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Revista Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos (11):12–23. http://www.bdigital.uncu.edu.ar/objetos_digitales/6820/02-divirgilio-esc11.pdf

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) (2010) Statistical Yearbook of Latin America and the Caribbean 2010. Economic commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/925/1/S1000780_es.pdf

Groisman F (2009) Segregación residencial socioeconómica en Argentina durante la recuperación económica (2002–2007). Working paper. Instituto de Estudios Latinoamericanos. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/3664346.pdf

Groisman F (2010) La persistencia de la segregación residencial socioeconómica en Argentina. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos 25(74):429–460. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20787558

INDEC (1991) 1991 National census of population and housing. National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, Buenos Aires

INDEC (2001) 2001 National census of population, households, and housing. National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, Buenos Aires

INDEC (2010) 2010 national census of population, households, and housing. National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, Buenos Aires

Marcińczak S, Tammaru T, Novák J, Gentile M, Kovács Z, Temelová J et al (2015) Patterns of socioeconomic segregation in the capital cities of fast-track reforming postsocialist countries. Ann Assoc Am Geogr 105(1):183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.968977

Marcos M (2009) Territorios fragmentados. La segregación socio-espacial en la Aglomeración Gran Buenos (1970–2000). Working paper. Cátedra de Demografía Social, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. http://www.catedras.fsoc.uba.ar/demografiasocial/infodeinv/II18.pdf

Marcos M, Mera G (2018) La dimensión territorial de las desigualdades sociodemográficas en Buenos Aires. Voces en el Fénix 8(71):14–23. http://www.vocesenelfenix.com/sites/default/files/pdf/02-Marcos-Mera.pdf

Molinatti F (2013) Segregación residencial socioeconómica en la ciudad de Córdoba (Argentina): Tendencias y patrones espaciales. Revista INVI 28(79):61–94. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-83582013000300003

Musterd S, Marcińczak S, van Ham M, Tammaru T (2015) Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities: increasing separation between poor and rich. Discussion paper. Institute for the Study of Labor

Rodríguez G (2016) Desigualdades socioeconómicas y segregación residencial en dos décadas de signo político y económico opuesto. La aglomeración Gran Buenos Aires entre 1991 y 2010. Cuaderno Urbano. Espacio, cultura, sociedad, 21(21):5–28. http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/cuba/v21n21/v21n21a01.pdf

Sabatini F (2006) La segregación social del espacio en las ciudades de América Latina. Working Paper. División de Programas Sociales, Departamento de Desarrollo Sostenible, Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/La-segregaci%C3%B3n-social-del-espacio-en-las-ciudades-de-Am%C3%A9rica-Latina.pdf

Sabatini F, Wormald G, Sierralta C, Peters P.A (2009) Residential segregation in santiago: scale-related effects and trends, 1992–2002. In: Robertsy BR, Wilson RH (eds.), Urban segregation and governance in the Americas, pp 121–143, Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Suárez AL (2011) Segregación residencial en la región metropolitana de Buenos Aires. In: Balian de Tagtachian B, Suárez AL (comps.), Pobreza y solidaridad social en la Argentina: aportes desde el enfoque de las capacidades humanas. Buenos Aires: Educa

Svampa M (2004) La brecha urbana. Countries y barrios privados en Argentina. Capital Intelectual, Buenos Aires

Tammaru T, Marcińczak S, Aunap R, van Ham M, Janssen H (2019) Relationship between income inequality and residential segregation of socioeconomic groups. Reg Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1540035

Tammaru T, Musterd S, van Ham M, Marcińczak S (2016) A multi-factor approach to understanding socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. In: Tammaru T, Marcińczak S, an Ham M, Musterd S (eds.), Socio-economic segregation in European capital cities. East meets West (1–29), Routledge, London

Torres H (1975) Evolución de los procesos de estructuración espacial urbana. El caso de Buenos Aires. Desarrollo Económico 15(58):281–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3466262

Torres H (2001) Cambios socioterritoriales em Buenos Aires durante la década de 1990. Eure 27(80):33–56. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612001008000003

Torres HG, Marques E, Ferreira PM, Bitar S (2003) Pobreza e espaço: padrões de segregação em São Paulo. Estudos Avançados 17(47):13–42

World Bank, Development Research Group (2019). Gini Index (World Bank estimate). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=AR. Accessed 19 Feb 2019

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Molinatti, F. (2021). Socio-Economic Residential Segregation in Greater Buenos Aires: Evidence of Persistent Territorial Fragmentation Processes. In: van Ham, M., Tammaru, T., Ubarevičienė, R., Janssen, H. (eds) Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_23

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_23

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64568-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64569-4

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)