Abstract

Self-efficacy is one of the most ubiquitous term found in social, psychological, counselling, education, clinical and health literatures. The purpose of this chapter is to describe and evaluate self-efficacy theory and the studies most relevant to the nursing context. This chapter provides an overview of the development of self-efficacy theory, its five components and the role of self-efficacy in promoting emotional and behavioural changes in a person’s life with health problems. This chapter also discusses the role of self-efficacy in nursing interventions by providing examples of studies conducted in health promotion in patients and academic performance of nursing students.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Albert Bandura derived the concept of self-efficacy from his psychological research [1]. Based on Bandura’ self-efficacy theory [2] which was later renamed social cognitive theory, self-efficacy was defined as the individual’s perception of one’s ability to perform particular behaviours through four processes [3] including cognitive, motivational, affective and selection processes. The stronger their cognitive perception of self-efficacy, the higher they set their goals and commitment to achieve these goals [4]. Through cognitive comparisons of one’s own standard and knowledge of their performance level, people will choose what challenges they have to meet and how much effort is needed to undertake or overcome those challenges. Motivation based on goals leads to perseverance to accomplish their goals. Perceived self-efficacy determines their level of motivation [5]. People’s affective processes influence how they control and manage threats such as stress and depression in life and thus a strong source of incentive motivation. It has been reported that affective processes have dual motivating roles. The more self-satisfaction people have, the more motivated they are in accomplishing their goals. On the other hand, the more self-dissatisfied people are, the more heightened efforts they will do to accomplish their set goals [6]. Thus, in social cognitive theory, Bandura [3] believes that self-efficacy plays a major role in self-regulation in appraising and exercising control over potential threats. Through the selection process, people can select beneficial social environments and exercise control over them as they can judge their capability of handling challenging activities [7].

2 Self-Efficacy Theory and Other Psychological Theories

Self-efficacy theory has been compared to other theoretical models mostly among psychological theories on explaining human behaviour so as to place self-efficacy in a larger context. Self-efficacy relates to how a person perceives his or her ability to feel, think, motivate and act upon to change particular behaviour. The person processes, weighs and integrates diverse sources of information concerning his or her capability and integrates choice behaviour and effort expenditure accordingly [1]. Expectations concerning mastery and efficacy their ability to perform such activities are related to how they see themselves in terms of self-concept and self-esteem. Self-concept is a term used to describe the person’s attitudes and beliefs about the self and what he or she is capable to doing well. On the other hand, self-esteem is one’s evaluation of their beliefs and assessment of their value as a person. If a person’s assessment of their self-concept and self-esteem is high, the more they will be able or competent enough to change their behaviour.

Self-efficacy is also compared to locus of control which refers to a person’s belief that one is capable of controlling outcomes through one’s own behaviour [8]. People’s locus of control can either be affected by external or internal forces. Self-efficacy focuses on the person’s belief in the ability to perform a specific task, and having a feeling of success and accomplishment is a form of reinforcement to effect behavioural change and an example of internal locus of control [9, 10]. Bandura [7, 11] argued that locus of control is a kind of outcome expectancy as it is concerned about whether a person’s behaviour can control outcomes. Self-efficacy expectancy refers to perceived subjective judgement on the effective execution of a course of action.

Self-efficacy theory has also been linked to intrinsic motivation theory [12]. Bandura [7, 11] purported that people must serve as agents of their own motivation and action. Self-motivation relies on goal setting and evaluation of one’s own behaviour which operate through internal comparison processes [13]. Motivation predicts performance outcomes as it is concerned with what task people want or need to accomplish and successfully achieving it to have incentive value that is satisfying and pleasurable [9].

3 Sources of Self-Efficacy

Bandura [14] emphasised the four major sources of self-efficacy. First is through mastery experiences in overcoming obstacles. Mastery experiences build coping skills and exercise control over potential threats. Second is through various experiences provided by social models and seeing people similar to themselves who are successfully performing similar behaviours. These experiences are considered as the most influencing source of efficacy. Third is their own belief that they have what it takes to succeed. Fourth is altering their negative emotions and misinterpreting their physiological states. Physiological state can affect the level of self-efficacy when they interpret their somatic symptoms based on aversive arousal [7, 15]. People who believe they can manage these threats tend to be less disturbed by them [16].

4 Concept Analyses of Self-Efficacy

Concept development is an important process to generate nursing knowledge which ultimately be used to build evidence-based practice [10]. Self-efficacy has been identified as a middle-range theory, that is recognised as a predictor of health behaviour change and health maintenance [17]. There are many publications in nursing literature regarding the broad concept of self-efficacy. In general, and as used across disciplines, the concept of self-efficacy has been described as self-regulation, self-care, self-monitoring, self-management and self-monitoring [18]. The concept of self-efficacy has been analysed extensively in different nursing and education disciplines to provide an in-depth understanding of the theory’s applicability. A number of methods such as Rodgers, Walker and Avant [19] and Wilson [20] have been used to conduct concept analysis of self-efficacy in terms of its defining attributes, antecedents and references. Below are some of the examples of concept analyses in nursing.

Liu [21] analysed the concept of self-efficacy and its relationship with self-management among elderly patients with type 2 diabetes in China using Walker’s and Avant [19] method. The analysis found that the defining attributes of self-efficacy among this population were “cognitive recognition of requisite specific techniques and skills, perceived expectations of outcomes of self-management, sufficient confidence in their ability to perform the self-management, and sustained efforts in diabetes management” (p. 230). Liu [21] found that the consequences of self-efficacy among the Chinese elderly with type 2 diabetes were adherence to the prescribed regimen and successful management of the disease which were influenced by having relevant knowledge about diabetes, family support and learning from other similar cases with diabetes.

White et al. [22] analysed the concept of self-efficacy in relation to symptom management in patients with cancer. If cancer patients are not able to manage their symptom, the outcomes would be increased symptom distress, poor prognosis, decreased quality of life (QoL) and survival [23]. White et al. [22] also used Walker’s and Avant [19] concept analysis method to determine the antecedents, defining attributes and consequences. For the patients with cancer, the attributes of self-efficacy are cognitive, affective processes, motivation, confidence, competence and awareness of how they perceive and evaluate the symptoms. Symptom awareness and management decisions are affected by the patients’ emotions and distress. Motivation, confidence and competence must all be present for symptom management. White et al. [22] reported that the consequences of having low self-efficacy in patients with cancer leads to increased distress, depression and anxiety, interference with treatment and potential for untreated malignancies. As self-efficacy for managing cancer symptoms is influenced positively or negatively, utilising individual care plans based on the attributes, antecedents and consequences of self-efficacy concept among these patients is needed.

Sims and Skarbek [24] conducted concept analysis of self-efficacy to examine if the levels of parental self-efficacy are correlated with nursing care delivery and developmental outcomes for parents and their infants. As with White et al. [22], confidence (the ability to trust oneself) and competence (the ability to perform in a given situation) emerged as the most prominent defining attributes of parental self-efficacy. Previous experiences with infants and observational learning were found to be antecedents of parental self-efficacy, and the consequences included “parental satisfaction in parenting role, parental well-being, positive parenting skills and beneficial health outcomes for children” (p. 11). They recommended further research to survey objective parents’ level of confidence with parenting and level of comfort in their role.

Using Rogers’ [25] concept analysis method, Voskuil and Robbins [26] examined the concept of youth physical activity self-efficacy due to the decline in physical activity from childhood to adolescents. They defined physical activity as “complex, multi-dimensional behaviour that involves bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscle with resultant increases in physiological attributes, including energy expenditure above the basal metabolic rate and physical fitness” (p. 2004). They found that youth self-efficacy involves self-appraisal process in their belief and action about their capability for physical activity. The antecedents include prior and current physical activity experiences, modelling of physical activity by other youths and strong social support networks. There are of course positive and negative consequences of physical activity self-efficacy in youth. For example, physiological state in children with cardiac defect can lower self-efficacy while mastery and satisfactory experiences from participating in sport result in higher self-efficacy. The authors suggested that examination of the development of physical activity self-efficacy is needed as well as developing theory-based interventions designed to increase the sources of self-efficacy and physical activity self-efficacy to promote physical activity among youth.

Self-efficacy is also a concept used in nursing education to bridge the theory–practice gap [27], acquisition of clinical skills, critical thinking and overall academic success [28, 29]. Robb [30] conducted a concept analysis of self-efficacy to identify behaviours needed for students’ goal attainment. It was noted that clinical simulations, cooperative learning and personalised classroom structure influence students’ level of self-efficacy. Students utilised Bandura’s [2] concept of vicarious experiences by relying on theory learned from the classroom, clinical experiences and by observing other nurses and their teachers perform certain procedures successfully. Verbal persuasion from teachers is often the sources of self-efficacy in nursing education. Robb [30] found that students’ low level of self-efficacy requires emotional and academic support and suggested that nurse educators should be aware of the strategies used by millennial students to gain information and how they provide feedback about students’ performance.

5 Self-Efficacy in Nursing Research

Self-efficacy theory has been receiving much attention as a predictor of behavioural change and self-care management in health-related and educational research. This may be partially attributed to the shift in the health care paradigm from a disease-centred (pathogenic) to a health-centred (salutogenic) orientation. The salutogenic orientation emphasises personal well-being and an ideal state of health as the ultimate goals and works towards achieving these, as opposed to the pathogenic approach, which is primarily based on identifying problems or diseases and only attempting to solve them [31, 32]. One of the major concepts of the salutogenic theory is the sense of coherence, which refers to an individual’s ability to adopt existing and potential resources to counter stress and promote health. It is measured based on one’s perceived value of the outcome of the behaviour (meaningfulness), one’s belief that the behaviour will actually lead to that outcome (comprehensibility), and one’s capability of successfully performing the behaviour (manageability), of which Antonovsky [32] drew analogous comparison to the three conditions for self-efficacious behaviour: self-efficacy beliefs, behavioural efficacy beliefs and the value of anticipated outcomes [33]. The salutogenic approach has much in common with Bandura’s self-efficacy theory [1] that highlighted perceived self-efficacy’s crucial influence on choice of behavioural settings. Antonovsky [32] drew reference to it stating how an individual with a strong sense of coherence would more likely choose to enter situations without evaluating it as stressful, or in stressful situations, would appraise a stressor as benign. Under the salutogenic umbrella, self-efficacy is one of the key components that drive health-promoting practices, behaviour and self-care management [34,35,36,37]. In a recent study, self-efficacy is found to be positively related to sense of coherence, with this association being the strongest among people with low sense of coherence [38]. Additionally, self-efficacy was found to have either a significant direct effect on behaviours [39,40,41] or it becomes a mediator between other psychological factors and health behaviour [42, 43].

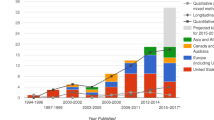

An electronic search was conducted on four databases (PsycInfo, PubMed, Embase and Cinahl) for English language articles that were published from each database’s inception up to December 2019. Keywords used revolved around the concept of self-efficacy in nursing and health care, such as “self-efficacy”, “chronic disease”, “nursing education”, and “patients”. The search generated a repertoire of studies, which primarily involved patients with chronic illnesses, parents during the perinatal period, nursing or medical students, and the youth or elderly population.

5.1 Use of Self-Efficacy in Health Promotion Among Patients with Chronic Illness

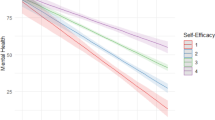

For patients with chronic medical conditions (e.g. sickle cell disease, asthma, cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease, cancer), higher levels of self-efficacy to manage their own chronic conditions are related to higher health-related QoL [44,45,46,47,48], reduced perceived stress [49,50,51], lesser anxiety and depressive symptoms [47, 48, 52] and lower symptom severity [48, 53] and also predict symptom resolution [49]. Similar results were found in mental illness studies examining unipolar and bipolar disorders, where higher self-efficacy was positively related to mental and physical health-related QoL [54, 55]. Conversely, a study on multi-morbid primary care patients reported that lower self-efficacy and higher disease burden leads to lower QoL [56]. The notable two-way relationship between certain predictors and outcomes highlights the complexity of addressing patient self-efficacy.

Given the rise in the ageing population and an increasing prevalence of chronic diseases [57], patient empowerment is imperative to reduce health care burden. Community and individual empowerment are one of the key health promotion principles stated in the Ottawa Charter for health promotion that focuses on enabling people to exercise more control over their health, environment and health choices [58]. Besides, an intervention study using an empowering self-management model that focused on self-awareness, goal setting, planning, adjusting physical, psychological and social structures, and evaluation was found to improve self-efficacy and sense of coherence among elderlies with chronic diseases [59]. In particular, self-efficacy is strongly related to the competence component of the empowerment concept, and it plays a critical role in the initiation and maintenance of positive behaviour change and is a vital mechanism for effective self-management [39, 60, 61]. Higher self-efficacy results in better self-management, which leads to improved health outcomes that not only reduce health care service burdens but also health care utilisation [36, 62, 63].

In terms of patient self-care and management, there is substantial evidence confirming the relationship between self-efficacy (both general and specific, e.g. pain self-efficacy) and self-management behaviours. Studies have identified a positive relationship between self-efficacy and opioid or medication adherence [61, 64,65,66,67], increased communication, partnership, self-care [37, 65] and positive patient-centred communication [68, 69]. A diabetes study reported diabetes management self-efficacy as the only predictor of diabetes control [70]. Higher education level and receiving health education were shown to boost management self-efficacy that was associated with self-care activities (i.e. nutrition, medication, physical exercise) and glycaemic control [70]. This also holds true for cancer patients, where self-efficacy and social support directly and indirectly affected self-management behaviours, specifically, patient communication (e.g. communicating concerns, asking questions, expressing treatment expectations), exercise and information seeking [71]. Pertaining to patients with physical disabilities, social functioning, stronger resilience and less pain and fatigue were strongly associated with disability management self-efficacy [72], which is crucial for increasing odds of employment among disabled youths [73].

Studies have identified a few predictors of self-efficacy among patients with chronic diseases such as duration of diagnosis, severity of disease symptoms, age, availability of social support and health education, and absence of complications and depression [74,75,76,77]. Of these variables, availability of social support and healthy literacy can easily be manipulated through intervention programs. Most studies have found a positive relationship between self-efficacy and health literacy, especially functional health literacy [77,78,79,80,81], but there are a few that found no significant associations between self-efficacy and health literacy [75, 82]. In addition, social support is a major factor affecting patients’ self-efficacy and self-management behaviours. Apart from boosting self-efficacy and self-management [71, 83, 84], higher social support was shown to reduce difficulties in medical interactions among breast cancer patients [85] and enhance well-being among diabetes patients [84]. Therefore, it is necessary for health care and educational interventions to include components of social support, health education when targeting patients’ management self-efficacy.

According to a recent review by Allegrante et al. [62], much of the empirical research and reviews that have been conducted on the effectiveness of interventions to support behavioural self-management of chronic diseases have demonstrated small to moderate effects for changes in health behaviours, health status, and health care utilisation for certain chronic conditions. Such interventions that targeted or examined self-efficacy as an outcome included web-based, mobile app-based and face-to-face educational training or programs. In Chao et al.’s [86] study, a cloud-based mobile health platform and mobile app service for diabetic patients to self-monitor progress and goals set was found to increase self-efficacy, improve health knowledge and increase behaviour compliance rate, especially in women. Ali and colleagues [87] reported higher pharmaceutical knowledge, patient satisfaction and self-efficacy among cardiovascular disease patients who were qualified to self-administer medication, as compared to those who were just provided educational brochures by nurses. In another study [88], an 8-week Patient and Partner Education Programme for Pituitary disease (PPEP-Pituitary) was found to increase patient and partner’s self-efficacy. Self-care behaviour and self-efficacy of asthma patients also improved after attending a self-efficacy intervention constituting educational videos, resources, social support group and phone-based medical follow-up [89]. Other interventions focused on caregivers’ self-efficacy by providing caregiver trainings and stress management trainings, which were effective in improving caregivers’ self-efficacy in managing patients’ symptoms, reducing caregiver stress and increasing preparedness in caregiving [90, 91]. The effectiveness of these interventions in improving self-efficacy suggests the importance of education, progress monitoring, information resources, social support, and patient–provider trust and communication in self-management behaviour, promoting interventions for patients with chronic diseases and their caregivers.

5.2 Role of Self-Efficacy in Parental Outcomes in the Perinatal Period

The emergence of self-efficacy studies on new parents or parents during the perinatal period has revealed the association of self-efficacy with childbirth and psychological well-being and childbirth outcomes. During pregnancy, maternal childbirth self-efficacy is positively correlated with vigour, sense of coherence, maternal support and childbirth knowledge, and negatively correlated with history of mental illnesses [92,93,94]. Moreover, maternal childbirth self-efficacy affects maternal well-being during pregnancy in terms of negative mood, anxiety, depressive symptoms and fear of childbirth [93,94,95,96]. The level of maternal self-efficacy also influences birth choices, with elective caesarean and higher dosage of analgesic epidural during childbirth being more common among mothers with lower childbirth self-efficacy [92,93,94, 97]. In order to better prepare mothers for childbirth, few studies have adopted a blended approach of antenatal mindfulness practice and skill-based education programs, which was effective in improving childbirth self-efficacy, mindfulness, reducing fear of childbirth, stress, antenatal depression, and opioid analgesic use [98,99,100]. The mindfulness programs also saw a reduction in postnatal depression, anxiety, and stress [98, 99]. Other studies that implemented antenatal psychoeducation programs also report increase in childbirth self-efficacy among mothers and reduction in fear of childbirth [101, 102].

After childbirth, receiving informal social support is essential for maternal parenting self-efficacy, which helps to reduce risk of postnatal depression [103]. A study by Salonen et al. [104] comparing parenting self-efficacy levels between mothers and fathers revealed that mothers tend to score higher than fathers on parenting self-efficacy. Age, multiparity, presence of depressive symptoms, perception of infant’s health and contentment, and quality of partner relationship were shown to be significant predictors of parenting self-efficacy in mothers and fathers [94, 104, 105]. Parenting self-efficacy not only is crucial for personal health and well-being but also contributes to healthy marital relations, family functioning and child development [106]. Therefore, various educational and technology-based interventions have been developed in hopes of boosting parental self-efficacy in the postpartum period. A postnatal psychoeducation program designed for the first-time mothers, consisting of a face-to-face educational session during a home visit, an educational booklet and three follow-up telephone calls was found to be effective at enhancing maternal self-efficacy, reducing postnatal depression, and increasing perceived social support [107]. A more recent technology-based Supportive Educational Parenting Program (SEPP) targeting both parents, comprised of two telephone-based educational sessions and 1 month follow-up via an educational mobile health app [108]. As compared to routine postpartum care, the SEPP was effective in promoting parenting self-efficacy, parenting satisfaction, parental bonding, better perceived social support and reducing postnatal depression in both mothers and fathers [108].

Self-efficacy in the postpartum period also includes breastfeeding. Dennis [109] reported significant predictors of breastfeeding self-efficacy as maternal education, support from other mothers, type of delivery, satisfaction with labour pain relief, satisfaction with postpartum care, perceptions of breastfeeding progress, infant feeding method as planned and maternal anxiety [109]. A study conducted among Japanese women found that breastfeeding self-efficacy is also associated with maternal perceptions of insufficient milk, leading to discontinuation of breastfeeding during the immediate postpartum period [110]. Breastfeeding is highly encouraged by health care professionals due to its nutritional value, benefits to the infant’s development and potential mother–child bonding; therefore, studies seek to develop educational or support programs to promote breastfeeding. During pregnancy, antenatal educational interventions using breastfeeding workbook or videos and demonstrations have shown to be effective in increasing mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy at 4 weeks postpartum [111, 112]. During the postpartum period, peer-support interventions for breastfeeding are more common [113]. Combined with professional support, peer-support breastfeeding programs are effective in boosting breastfeeding self-efficacy [113].

Despite the heavy focus on maternal self-efficacy during and after pregnancy, there has also been an increase in health care research on fathers’ involvement during the perinatal period, as early paternal involvement during and after pregnancy was found to positively influence maternal well-being and benefit the biopsychosocial development of infants 14 months and below [114,115,116]. A recent study by Shorey et al. [117] found that high paternal self-efficacy is one of the main factors of high paternal involvement during infancy, especially among first-time fathers. Higher paternal self-efficacy also leads to increase in parenting satisfaction over the first 6 months postpartum [118]. According to a review on informational interventions aiming to improve paternal outcomes [117], there were only three interventions (via online dissemination of information or self-modelled videotaped interaction and feedback) that reported on paternal self-efficacy [119,120,121], but only Hudson et al.’s [119] study found an intervention effect on parenting self-efficacy and parenting satisfaction in fathers. In addition to informational interventions, educational interventions are also useful and important in boosting paternal self-efficacy and other paternal outcomes [108, 122].

Overall, in order to effectively enhance parental self-efficacy across these various aspects (i.e. childbirth, parenting, breastfeeding) during the perinatal period, it is necessary for interventions to incorporate and target at least a component of the self-efficacy theory (mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological arousal).

5.3 Role of Self-Efficacy in Nursing Education

Another application of self-efficacy in the health care setting is with regard to nursing education and training. Effective clinical trainings should establish a sense of self-efficacy among nursing students, which is a key component for acting independently and competently in the nursing profession [123,124,125]. Students’ clinical performance, course completion and achievement motivations are also dependent on individual perceived self-efficacy [125,126,127]. According to Bandura [128], students with low self-efficacy will tend to avoid situations that led to past failures; therefore, strong sense of self-efficacy and job satisfaction is crucial in reducing attrition in the nursing profession [126, 129]. Lastly, as a future health care practitioner, clinical self-efficacy and competence are essential for providing quality health care and ensuring patient safety [125].

Evidence has suggested that older age, being married, more working experience in the nursing field, individual interest and willingness to work in a nursing unit contributes to high nursing self-efficacy in students [127, 130, 131], which is also an important factor in creating clinical confidence [132]. Clinical environments, nursing colleagues, and clinical educator’s capabilities can influence the creation of clinical self-efficacy in nursing students [123]. A weak relationship between faculty and hospitals, lack of staff and training facilities, and unprofessional trainers could adversely influence self-efficacy [133, 134]. More specifically, students have reported that using logbooks, having more authentic clinical simulations, working alone, more ward time, being under the guidance of one instructor, and receiving constant verbal validation, positive feedback and support can increase one’s own sense of self-efficacy [123, 135, 136]. These corresponds with components of the self-efficacy theory [128] in terms of mastery experiences, vicarious experiences and verbal persuasion.

Numerous education and clinical training curriculums are being developed and constantly revised to target promotion of self-efficacy in specific clinical skills among nursing students. Sabeti and colleagues [137] found that students’ self-efficacy ranges from weak to excellent across different skills, with high self-efficacy in medication administration and nursing procedures, and low self-efficacy in care before, during and after diagnostic procedures. In Pike et al.’s study [136], despite undergoing a clinical simulation program aimed to improve learning self-efficacy, students still reported low self-efficacy in communication skills. However, in another study, a blended learning pedagogy was used to redesign a nursing communication module from didactic lectures to an online and face-to-face interactive classroom sessions, which resulted in increased communication self-efficacy and better learning attitudes among nursing students [138]. In nursing education, clinical simulations are widely used to create authentic scenarios and training environments and were often the most effective method in boosting students’ self-efficacy. A study comparing the effectiveness of a peritoneal dialysis simulation with watching videos reported higher psychomotor skills score and self-efficacy among students who underwent the simulation than those who just watched videos of the procedure [139]. Similarly, a Diverse Standardised Patient Simulation was also seen to improve students’ transcultural self-efficacy perceptions [140]. Notably, simulation exercises were more effective at improving students’ self-efficacy and critical thinking skills when conducted after a role-play than after a lecture [141]. Overall, nursing curriculum and clinical simulations play a vital role in mastery experiences, and the integration of positive feedback (verbal persuasion) and observation of clinical educators in ward settings (vicarious experiences) would present an ideal method of enhancing self-efficacy among nursing students.

6 Conclusion

The self-efficacy theory is in itself linked with other psychological theories to influence health-promoting behavioural changes in various life situations. The applications of self-efficacy in various nursing contexts ultimately boil down to health promotion and improvement of the quality of health care and patient safety. The concept of self-efficacy has played a significant role in not only predicting individual physical and psychological wellbeing, competencies, and self-care management, but also often serve as a theoretical framework for existing clinical and educational interventions. Despite its well-established literature base, emerging evidence on self-efficacy’s positive relationship with sense of coherence and the gradual shift of the health care paradigm to a salutogenic orientation indicate a need for subsequent nursing research to continue to tailor and refine ways to enhance self-efficacy in specific population groups.

Take Home Messages

-

Self-efficacy is an individual’s perception of their own ability to perform a particular behaviour through cognitive, motivational, affective and selection processes.

-

Self-efficacy is derived from mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion and individual emotional and physiological state.

-

Self-efficacy theory is commonly compared to other psychological behaviour theories such as locus of control, self-esteem and intrinsic motivation theory.

-

The self-efficacy theory is analogous to Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory where self-efficacy is also discovered to be positively associated with sense of coherence.

-

The concept of self-efficacy is applied in self-regulation, self-care, self-monitoring and self-management in the nursing context.

-

Self-efficacy promotes patients’ competence that is vital for self-care and management and is associated with better physical and psychological health among chronically ill patients.

-

High maternal self-efficacy is crucial for positive childbirth and breastfeeding experiences, and better psychological well-being during and after pregnancy.

-

High paternal self-efficacy increases paternal involvement during infancy and parenting satisfaction.

-

In nursing education, self-efficacy plays a vital role in enhancing students’ competence, motivation and clinical performance, which influences job satisfaction and quality of patient care provided.

-

Education and social support through informational, emotional, formal and informal means are the primary contributors to self-efficacy.

-

Overall, self-efficacy is a key health-promoting component among patients with chronic illnesses, parents during the perinatal period, youth and the elderly.

References

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in physiological activation and health-promoting behavior. New York: Raven; 1989.

Bandura A. Recycling misconceptions of perceived self-efficacy. Cognit Ther Res. 1984;8(3):231–55.

Bandura A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol. 1989;44(9):1175.

Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy: thought control of action. Hoboken, NJ: Taylor & Francis; 2014.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Rotter JB. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr Gen Appl. 1966;80(1):1.

Maddux JE, Rogers RW. Protection motivation and self-efficacy: a revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1983;19(5):469–79.

Zulkosky K, editor. Self-efficacy: a concept analysis. Nursing forum: Wiley Online Library; 2009.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1997.

Deci EL. SpringerLink. Intrinsic motivation. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1975.

Bandura A, Schunk DH. Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1981;41(3):586–98.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behaviour. New York: Academic Press; 1994. p. 71–81.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am Psychol. 1982;37(2):122.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1995.

Carpenito LJ. Nursing diagnosis: application to clinical practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2009.

Novak M, Costantini L, Schneider S, Beanlands H, editors. Approaches to self-management in chronic illness. Seminars in dialysis, vol. 26: Wiley Online Library; 2013. p. 188.

Walker LO, Avant KC. Strategies for theory construction in nursing. Norwalk: Appleton & Lange; 2005.

Wilson J. Thinking with concepts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1969.

Liu T. A concept analysis of self-efficacy among Chinese elderly with diabetes mellitus. Nurs Forum. 2012;47(4):226–35.

White LL, Cohen MZ, Berger AM, Kupzyk KA, Swore-Fletcher BA, Bierman PJ. Perceived self-efficacy: a concept analysis for symptom management in patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21(6):E272–e9.

Gapstur RL. Symptom burden: a concept analysis and implications for oncology nurses. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34(3):673–80.

Sims DC, Skarbek AJ. Parental Self-efficacy: a concept analysis related to teen parenting and implications for school nurses. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35(1):8–14.

Rodgers BL, Knafl K. Concept analysis: an evolutionary view, concept development in nursing: foundations. Tech Appl. 2000:77–102.

Voskuil VR, Robbins LB. Youth physical activity self-efficacy: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(9):2002–19.

Kuiper R, Pesut D, Kautz D. Promoting the self-regulation of clinical reasoning skills in nursing students. Open Nurs J. 2009;3:76–85.

Bambini D, Washburn J, Perkins R. Outcomes of clinical simulation for novice nursing students: communication, confidence, clinical judgment. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2009;30(2):79–82.

Blackman I, Hall M, Darmawan IJIEJ. Undergraduate nurse variables that predict academic achievement and clinical competence in. Nursing. 2007;8(2):222–36.

Robb M. Self-efficacy with application to nursing education: a concept analysis. Nurs Forum. 2012;47(3):166–72.

Antonovsky A. Health, stress, and coping. London: Jossey-Bass; 1979.

Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. London: Jossey-Bass; 1987.

Saltzer EB. The relationship of personal efficacy beliefs to behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 1982;21(3):213–21.

Eriksson M, Mittelmark MB. The sense of coherence and its measurement. In: Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, Bauer GF, Pelikan JM, Lindstrom B, et al., editors. The handbook of Salutogenesis, vol. 2017. Cham: Springer. p. 97–106.

Lindström B, Eriksson M. The Hitchhiker’s guide to salutogenesis: Salutogenic pathways to health promotion: Folkhälsan Research Center, Health Promotion Research; 2010.

Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Bandura A, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–23.

Sarkar U, Fisher L, Schillinger D. Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care. 2006;29(4):823–9.

Trap R, Rejkjaer L, Hansen EH. Empirical relations between sense of coherence and self-efficacy, National Danish Survey. Health Promot Int. 2016;31(3):635–43.

Baldwin AS, Rothman AJ, Hertel AW, Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Finch EA, et al. Specifying the determinants of the initiation and maintenance of behavior change: an examination of self-efficacy, satisfaction, and smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):626–34.

Hendriksen ES, Pettifor A, Lee S-J, Coates TJ, Rees HV. Predictors of condom use among young adults in South Africa: the reproductive health and HIV research unit National Youth Survey. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1241–8.

Scholz U, Sniehotta FF, Schwarzer R. Predicting physical exercise in cardiac rehabilitation: the role of phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27(2):135–51.

Darker CD, French DP, Eves FF, Sniehotta FF. An intervention to promote walking amongst the general population based on an 'extended' theory of planned behaviour: a waiting list randomised controlled trial. Psychol Health. 2010;25(1):71–88.

Motl RW, Dishman RK, Saunders RP, Dowda M, Felton G, Ward DS, et al. Examining social-cognitive determinants of intention and physical activity among black and White adolescent girls using structural equation modeling. Health Psychol. 2002;21(5):459–67.

Adegbola M. Spirituality, self-efficacy, and quality of life among adults with sickle cell disease. South Online J Nurs Res. 2011;11(1):5.

Akin S, Kas Guner C. Investigation of the relationship among fatigue, self-efficacy and quality of life during chemotherapy in patients with breast, lung or gastrointestinal cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2019;28(1):e12898.

Börsbo B, Gerdle B, Peolsson M. 988 impact of the interaction between self efficacy, symptoms, and catastrophizing on disability, quality of life, and health in chronic pain patients. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(S1):S277–S8.

Chao CY, Lemieux C, Restellini S, Afif W, Bitton A, Lakatos PL, et al. Maladaptive coping, low self-efficacy and disease activity are associated with poorer patient-reported outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(3):159–66.

Omran S, Symptom Severity MMS. Anxiety, depression, self-efficacy and quality of life in patients with Cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(2):365–74.

Byma EA, Given BA, Given CW, You M. The effects of mastery on pain and fatigue resolution. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36(5):544–52.

Fleming G, McKenna M, Murchison V, Wood Y, Nixon JO, Rogers T, et al. Using self-efficacy as a client-centred outcome measure. Nurs Stand. 2003;17(34):33–6.

Hoffman AJ, von Eye A, Gift AG, Given BA, Given CW, Rothert M. Testing a theoretical model of perceived self-efficacy for cancer-related fatigue self-management and optimal physical functional status. Nurs Res. 2009;58(1):32–41.

Sympa P, Vlachou E, Kazakos K, Govina O, Stamatiou G, Lavdaniti M. Depression and self-efficacy in patients with type 2 diabetes in northern Greece. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2018;18(4):371–8.

Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Stommel M, Given CW, Given B. Physical functioning and depression among older persons with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(1):11–8.

Abraham KM, Miller CJ, Birgenheir DG, Lai Z, Kilbourne AM. Self-efficacy and quality of life among people with bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(8):583–8.

Houle J, Gascon-Depatie M, Bélanger-Dumontier G, Cardinal C. Depression self-management support: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(3):271–9.

Peters M, Potter CM, Kelly L, Fitzpatrick R. Self-efficacy and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of primary care patients with multi-morbidity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):37.

WHO. The world health report 2002: reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

WHO. The Ottawa charter for health promotion. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986.

Hourzad A, Pouladi S, Ostovar A, Ravanipour M. The effects of an empowering self-management model on self-efficacy and sense of coherence among retired elderly with chronic diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:2215–24.

Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7.

Nafradi L, Nakamoto K, Schulz PJ. Is patient empowerment the key to promote adherence? A systematic review of the relationship between self-efficacy, health locus of control and medication adherence. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186458.

Allegrante JP, Wells MT, Peterson JC. Interventions to support behavioral self-management of chronic diseases. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):127–46.

Marks R, Allegrante JP. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):148–56.

Archiopoli A, Ginossar T, Wilcox B, Avila M, Hill R, Oetzel J. Factors of interpersonal communication and behavioral health on medication self-efficacy and medication adherence. AIDS Care. 2016;28(12):1607–14.

Curtin RB, Walters BAJ, Schatell D, Pennell P, Wise M, Klicko K. Self-efficacy and self-management behaviors in patients with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15(2):191–205.

Liang SY, Yates P, Edwards H, Tsay SL. Factors influencing opioid-taking self-efficacy and analgesic adherence in Taiwanese outpatients with cancer. Psychooncology. 2008;17(11):1100–7.

McCann TV, Clark E, Lu S. The self-efficacy model of medication adherence in chronic mental illness. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(11c):329–40.

Austin JD, Robertson MC, Shay LA, Balasubramanian BA. Implications for patient-provider communication and health self-efficacy among cancer survivors with multiple chronic conditions: results from the health information National Trends Survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(5):663–72.

Finney Rutten LJ, Hesse BW, St Sauver JL, Wilson P, Chawla N, Hartigan DB, et al. Health Self-efficacy among populations with multiple chronic conditions: the value of patient-centered communication. Adv Ther. 2016;33(8):1440–51.

Amer FA, Mohamed MS, Elbur AI, Abdelaziz SI, Elrayah ZA. Influence of self-efficacy management on adherence to self-care activities and treatment outcome among diabetes mellitus type 2. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2018;16(4):1274.

Geng Z, Ogbolu Y, Wang J, Hinds PS, Qian H, Yuan C. Gauging the effects of Self-efficacy, social support, and coping style on self-management behaviors in Chinese cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(5):E1–E10.

Amtmann D, Bamer AM, Nery-Hurwit MB, Liljenquist KS, Yorkston K. Factors associated with disease self-efficacy in individuals aging with a disability. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(10):1171–81.

Andersén Å, Larsson K, Pingel R, Kristiansson P, Anderzén I. The relationship between self-efficacy and transition to work or studies in young adults with disabilities. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(2):272–8.

Kang Y, Yang IS. Cardiac self-efficacy and its predictors in patients with coronary artery diseases. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(17–18):2465–73.

Lee H, Lim Y, Kim S, Park HK, Ahn JJ, Kim Y, et al. Predictors of low levels of self-efficacy among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in South Korea. Nurs Health Sci. 2014;16(1):78–83.

Sanchez AI, Martinez MP, Miro E, Medina A. Predictors of the pain perception and self-efficacy for pain control in patients with fibromyalgia. Span J Psychol. 2011;14(1):366–73.

Xu XY, Leung AYM, Chau PH. Health literacy, self-efficacy, and associated factors among patients with diabetes. Health Literacy Res Pract. 2018;2(2):e67–77.

Bohanny W, Wu SFV, Liu CY, Yeh SH, Tsay SL, Wang TJ. Health literacy, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2013;25(9):495–502.

Inoue M, Takahashi M, Kai I. Impact of communicative and critical health literacy on understanding of diabetes care and self-efficacy in diabetes management: a cross-sectional study of primary care in Japan. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14(1):40.

Reisi M, Tavassoli E, Mahaki B, Sharifirad G, Javadzade H, Mostafavi F. Impact of health literacy, self-efficacy and outcome expectations on adherence to self-care behaviors in Iranians with type 2 diabetes. Oman Med J. 2016;31(1):52–9.

Zuercher E, Diatta ID, Burnand B, Peytremann-Bridevaux I. Health literacy and quality of care of patients with diabetes: a cross-sectional analysis. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(3):233–40.

Murphy DA, Lam P, Naar-King S, Harris DR, Parsons JT, Muenz LR. Health literacy and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79(1):25–9.

Lee YH, Wang RH. Helplessness, social support and self-care behaviors among long-term hemodialysis patients. Nurs Res. 2001;9(2):147.

Schiotz ML, Bogelund M, Almdal T, Jensen BB, Willaing I. Social support and self-management behaviour among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29(5):654–61.

Collie K, Wong P, Tilston J, Butler LD, Turner-Cobb J, Kreshka MA, et al. Self-efficacy, coping, and difficulties interacting with health care professionals among women living with breast cancer in rural communities. Psychooncology. 2005;14(10):901–12.

Chao DY, Lin TM, Ma W-Y. Enhanced self-efficacy and behavioral changes among patients with diabetes: cloud-based mobile health platform and Mobile App Service. JMIR Diabetes. 2019;4(2):e11017.

Ali Beigloo RH, Mohajer S, Eshraghi A, Mazlom SR. Self-administered medications in cardiovascular ward: a study on patients’ self-efficacy, knowledge and satisfaction. J Evid Based Care. 2019;9(1):16–25.

Andela CD, Repping-Wuts H, Stikkelbroeck N, Pronk MC, Tiemensma J, Hermus AR, et al. Enhanced self-efficacy after a self-management programme in pituitary disease: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;177(1):59–72.

Chen SY, Sheu S, Chang CS, Wang TH, Huang MS. The effects of the self-efficacy method on adult asthmatic patient self-care behavior. J Nurs Res. 2010;18(4):266–74.

Havyer RD, Havyer RD, van Ryn M, van Ryn M, Wilson PM, Wilson PM, et al. The effect of routine training on the self-efficacy of informal caregivers of colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(4):1071–7.

Hendrix CC, Hendrix CC, Bailey DE Jr, Bailey DE Jr, Steinhauser KE, Steinhauser KE, et al. Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(1):327–36.

Berentson-Shaw J, Scott KM, Jose PE. Do self-efficacy beliefs predict the primiparous labour and birth experience? A longitudinal study. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2009;27(4):357–73.

Carlsson I-M, Ziegert K, Nissen E, Hälsofrämjande P, Centrum för forskning om välfärd hoi, Akademin för hälsa och v, et al. The relationship between childbirth self-efficacy and aspects of well-being, birth interventions and birth outcomes. Midwifery. 2015;31(10):1000–7.

Schwartz L, Toohill J, Creedy DK, Baird K, Gamble J, Fenwick J. Factors associated with childbirth self-efficacy in Australian childbearing women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:29.

Salomonsson B, Gullberg MT, Alehagen S, Wijma K. Self-efficacy beliefs and fear of childbirth in nulliparous women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;34(3):116–21.

Sieber S, Germann N, Barbir A, Ehlert U. Emotional well-being and predictors of birth-anxiety, self-efficacy, and psychosocial adaptation in healthy pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(10):1200–7.

Dilks FM, Beal JA. Role of self-efficacy in birth choice. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1997;11(1):1–9.

Byrne J, Hauck Y, Fisher C, Bayes S, Schutze R. Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based childbirth education pilot study on maternal self-efficacy and fear of childbirth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2014;59(2):192–7.

Duncan LG, Cohn MA, Chao MT, Cook JG, Riccobono J, Bardacke N. Benefits of preparing for childbirth with mindfulness training: a randomized controlled trial with active comparison. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):140–11.

Pan W-L, Chang C-W, Chen S-M, Gau M-L. Assessing the effectiveness of mindfulness-based programs on mental health during pregnancy and early motherhood—a randomized control trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):346.

Sercekus P, Baskale H. Effects of antenatal education on fear of childbirth, maternal self-efficacy and parental attachment. Midwifery. 2016;34:166–72.

Toohill J, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Buist A, Turkstra E, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a psycho-education intervention by midwives in reducing childbirth fear in pregnant women. Birth. 2014;41(4):384–94.

Leahy-Warren P, McCarthy G, Corcoran P. First-time mothers: social support, maternal parental self-efficacy and postnatal depression. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(3–4):388–97.

Salonen AH, Kaunonen M, Åstedt-Kurki P, Järvenpää AL, Isoaho H, Tarkka MT. Parenting self-efficacy after childbirth. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2324–36.

Bryanton J, Gagnon AJ, Hatem M, Johnston C. Predictors of early parenting self-efficacy: results of a prospective cohort study. Nurs Res. 2008;57(4):252–9.

Albanese AM, Russo GR, Geller PA. The role of parental self-efficacy in parent and child well-being: a systematic review of associated outcomes. Child Care Health Dev. 2019;45(3):333–63.

Shorey S, Chan SWC, Chong YS, He HG. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of a postnatal psychoeducation programme on self-efficacy, social support and postnatal depression among primiparas. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(6):1260–73.

Shorey S, Ng YPM, Ng ED, Siew AL, Mörelius E, Yoong J, et al. Effectiveness of a technology-based supportive educational parenting program on parental outcomes (part 1): randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(2):e10816.

Dennis CLE. Identifying predictors of breastfeeding self-efficacy in the immediate postpartum period. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(4):256–68.

Otsuka K, Dennis C-L, Tatsuoka H, Jimba M. The relationship between breastfeeding self-efficacy and perceived insufficient milk among Japanese mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37(5):546–55.

Mizrak B, Ozerdogan N, Colak E. The effect of antenatal education on breastfeeding self-efficacy: primiparous women in Turkey. Int J Caring Sci. 2017;10(1):503–10.

Otsuka K, Taguri M, Dennis C-L, Wakutani K, Awano M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Effectiveness of a breastfeeding self-efficacy intervention: do hospital practices make a difference? Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(1):296–306.

Kaunonen M, Hannula L, Tarkka MT. A systematic review of peer support interventions for breastfeeding. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(13–14):1943–54.

Bronte-Tinkew J, Carrano J, Horowitz A, Kinukawa A. Involvement among resident fathers and links to infant cognitive outcomes. J Fam Issues. 2008;29(9):1211–44.

Shorey S, He H-G, Morelius E. Skin-to-skin contact by fathers and the impact on infant and paternal outcomes: an integrative review. Midwifery. 2016;40:207–17.

Stapleton LRT, Schetter CD, Westling E, Rini C, Glynn LM, Hobel CJ, et al. Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26(3):453–63.

Shorey S, Ang L, Tam WWS. Informational interventions on paternal outcomes during the perinatal period: a systematic review. Women Birth. 2019;32(2):e145–e58.

Shorey S, Ang L, Goh ECL, Gandhi M. Factors influencing paternal involvement during infancy: a prospective longitudinal study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(2):357–67.

Hudson DB, Campbell-Grossman C, Ofe Fleck M, Elek SM, Shipman AMY. Effects of the new fathers network on first-time fathers’ parenting self-efficacy and parenting satisfaction during the transition to parenthood. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 2003;26(4):217–29.

Magill-Evans J, Harrison M, Benzies K, Gierl M, Kimak C. Effects of parenting education on first-time fathers’ skills in interactions with their infants. Fathering. 2007;5(1):42–57.

Salonen AH, Kaunonen M, Åstedt-Kurki P, Järvenpää A-L, Isoaho H, Tarkka M-T. Effectiveness of an internet-based intervention enhancing Finnish parents’ parenting satisfaction and parenting self-efficacy during the postpartum period. Midwifery. 2011;27(6):832–41.

Shorey S, Lau YY, Dennis CL, Chan YS, Tam WWS, Chan YH. A randomized-controlled trial to examine the effectiveness of the ‘home-but not alone’ mobile-health application educational programme on parental outcomes. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73(9):2103–17.

Abdal M, Masoudi Alavi N, Adib-Hajbaghery M. Clinical self-efficacy in senior nursing students: a mixed-methods study. Nurs Midwif Stud. 2015;4(3):e29143.

Dearnley CA, Meddings FS. Student self-assessment and its impact on learning—a pilot study. Nurse Educ Today. 2007;27(4):333–40.

Mohamadirizi S, Kohan S, Shafei F, Mohamadirizi S. The relationship between clinical competence and clinical self-efficacy among nursing and midwifery students. Int J Pediatr. 2015;3(6.2):1117–23.

McLaughlin K, Moutray M, Muldoon OT. The role of personality and self-efficacy in the selection and retention of successful nursing students: a longitudinal study. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(2):211–21.

Zhang Z-J, Zhang C-L, Zhang X-G, Liu X-M, Zhang H, Wang J, et al. Relationship between self-efficacy beliefs and achievement motivation in student nurses. Chin Nurs Res. 2015;2(2):67–70.

Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educ Psychol. 1993;28(2):117–48.

Lee TW, Ko YK. Effects of self-efficacy, affectivity and collective efficacy on nursing performance of hospital nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(4):839–48.

Reid C, Jones L, Hurst C, Anderson D. Examining relationships between socio-demographics and self-efficacy among registered nurses in Australia. Collegian. 2018;25(1):57–63.

Soudagar S, Rambod M, Beheshtipour N. Factors associated with nurses’ self-efficacy in clinical setting in Iran, 2013. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20(2):226–31.

Boi S. Nurses’ experiences in caring for patients from different cultural backgrounds. NT Res. 2000;5(5):382–9.

Ekstedt M, Lindblad M, Löfmark A. Nursing students’ perception of the clinical learning environment and supervision in relation to two different supervision models—a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2019;18(1):49.

Nabolsi M, Zumot A, Wardam L, Abu-Moghli F. The experience of Jordanian nursing students in their clinical practice. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2012;46:5849–57.

Gibbons C. Stress, coping and burn-out in nursing students. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(10):1299–309.

Pike T, O’Donnell V. The impact of clinical simulation on learner self-efficacy in pre-registration nursing education. Nurse Educ Today. 2010;30(5):405–10.

Sabeti F, Akbari-nassaji N, Haghighy-zadeh MH. Nursing students’ self-assessment regarding clinical skills achievement in Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (2009). IJME. 2011;11(5):506–15.

Shorey S, Kowitlawakul Y, Devi MK, Chen HC, Soong SKA, Ang E. Blended learning pedagogy designed for communication module among undergraduate nursing students: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;61:120–6.

Topbas E, Terzi B, Gorgen O, Bingol G. Effects of different education methods in peritoneal dialysis application training on psychomotor skills and self-efficacy of nursing students. Technol Health Care. 2019;27(2):175–82.

Ozkara SE. Effect of the diverse standardized patient simulation (DSPS) cultural competence education strategy on nursing students’ transcultural self-efficacy perceptions. J Transcult Nurs. 2019;30(3):291–302.

Kim E. Effect of simulation-based emergency cardiac arrest education on nursing students’ self-efficacy and critical thinking skills: role play versus lecture. Nurs Educ Today. 2018;61:258–63.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shorey, S., Lopez, V. (2021). Self-Efficacy in a Nursing Context. In: Haugan, G., Eriksson, M. (eds) Health Promotion in Health Care – Vital Theories and Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63135-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-63134-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-63135-2

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)