Abstract

Nowadays, in the era of flexible and precarious employment, the concept of a ‘career for life’ in one organisation appears to be redundant, as most employees in the global labour market do not have permanent employment (ILO, World employment and social outlook: the changing nature of jobs. Geneva: International Labour Office, 2015). This chapter focuses on the shipping industry as an example of a global industry that employs over a million seafarers (BIMCO, Manpower 2005 update: the worldwide demand for and supply of seafarers. Warwick: Warwick Institute for Employment Research, 2015) as their main labour force in what could termed flexible employment. The chapter explores the idea of having a ‘career’ within the precarious shipping industry by focusing on the reasons for joining, staying, and leaving a seafaring occupation. The chapter is based on existing literature, and on recent data that was collected as part of a study on seafarers’ career development.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The notion of a ‘career for life’ in the global labour market has been under scrutiny in the last four decades or so, as flexible employment, which refers to contractual and temporary work, has become the norm in many companies worldwide (Brown 1995; Baruch 2006; Baruch and Peiperl 2000; Sampson 2013; Stone 2005). A major feature of this change has been a shift from jobs offering life-long job security to work on temporary contracts (Stone 2005; Burgess 1997). Although there are still organisations that offer long-term secure careers to their employees, it is in fact the ‘norm’ for most people (approximately 75% of the world population) not to have a permanent job (ILO 2015, 2019). Such a lack of permanency can result in people accepting a series of contract-based, short-term jobs which may have long-term consequences for their future career development. Consequently, some individuals are compelled to plan a skill-based career, in which their working life is constructed by way of a series of short-term positions enabling them to gain skills that they hope will assist them in finding better employment, often across different organisations and industries. This kind of career structure is referred to as a portfolio career (Cohen and Mallon 1999; Mallon 1998).

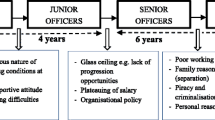

In the past, seafaring was considered to be a life-long occupation (Baum-Talmor 2018; Glen and McConville 2001; Hill 1972; Mack 2007), offering hierarchical advancement and job security Nowadays, despite the hierarchical structure of the work division and roles on board, the attitude towards the longevity of the seafaring career has shifted, and it is no longer considered to be a ‘job for life’ for most individuals (Alderton et al. 2004; Baum-Talmor 2018; Gould 2011; Sampson 2013).

Shipping is an example of a global sector which utilises flexible employment on a regular basis. Such flexible employment is generally associated with the offshoring and outsourcing of recruitment to third-party agencies (Sampson 2013; Bloor and Sampson 2009; Fei 2011; Alderton et al. 2004; Sampson and Schroeder 2006). These modifications in industry employment and recruitment strategies have caused the origins of seafarers that join the industry to change. In the past seafarers from developed countries made up the majority of the workforce, according to BIMCO (Baltic and International Maritime Council) whereas at present the seafaring profession has become more dominated by individuals from developing countries (BIMCO 2005, 2010, 2015). The latest available manpower report (BIMCO 2015) suggests that it is anticipated that there will be a decline in officers originating from OECD countries in the next few years with a concomitant increase in seafarers from developing countries (BIMCO 2015, p. 34).

Within the context of such changes it is important to appreciate that whilst some jobs at sea are relatively unskilled (those of ‘ratings’) (Barnett et al. 2006; Klikauer and Morris 2002), others are highly skilled (those of ‘officers’) (Hill 1972; Mack 2007; Sampson 2013; Zurcher 1965). Formerly jobs with a high-skill requirement necessitated a considerable amount of training and were likely to be permanent. In contrast relatively unskilled work was more likely to be offered on a ‘casual basis’. However it seems that this is no longer the case as employers are demonstrating a lesser degree of commitment to the long term training and development of their officers (Sampson and Tang 2015).

This chapter seeks to explain the attractions of seafaring which is a relatively dangerous occupation (Baum-Talmor 2018; Belousov et al. 2007; Sampson 2013), has precarious employment prospects and requires long periods of time to be spent away from home (Acejo 2012; Baum-Talmor 2012; Sampson 2013). Specifically it is of interest to consider the influences that might continue to steer individuals towards a ‘career’ in the modern cargo shipping industry, and to examine whether individuals nowadays perceive seafaring as a ‘career’ for life or a temporary job.

In order to address these issues, data that relates directly to the reasons seafarers join and stay in this occupation were collected and analysed.Footnote 1 My focus has been on current seafarers rather than retired seafarers and therefore insights into the reasons for leaving this occupation are based on seafarers’ intentions as expressed during the interviews, which are complemented and enhanced by the existing literature. As part of the data collection, non-participant observation was conducted on board a cargo ship, which enabled a direct glimpse into seafarers’ working routines. The use of an immersive research technique enabled a holistic view of the circumstances behind the choice of seafaring as an occupation. In addition to observation on board, in-depth interviews with key participants in the shipping industry were conducted and included interviews with seafarers, crew managers and recruiters. This provided direct input regarding seafarers’ occupational choices. This chapter draws upon 56 formal interviews and 15 informal conversations. The seafarers in the research came from various backgrounds and nationalities and the categorisation used previously by the International Monetary Fund (IMF 2015, 2019) is utilised here, dividing these seafarers into those coming from developed countries (n = 11) and those from emerging nations and developing countries (n = 45).

Going to Sea: Influences on Joining

One of the common reasons for going to sea is to earn a good salary. This is seen by many individuals as adequate compensation for the hardships involved in such a career choice. In a variety of studies seafarers from countries like the Philippines, UK, Ecuador and Taiwan identify ‘good pay’ in the seafaring occupation as the main reason for choosing to join seafaring (Gould 2010; Seaways2014; Baylon and Stevenson 2005; Østreng 2000; Calderón 2011; Guo et al. 2006). In my research both seafarers and recruitment agencies identified finance as the prime motivation for the choice of a job at sea. For example, Roslin, a crew manager from the Philippines, revealed:

Usually, from Philippines side, [the reason to join seafaring] is always money. It is always that. […] Well, given the economy of the Philippines, it’s like there is no other option. […] Let’s talk about an OS [Ordinary Seaman], that’s the entry level [of a seafarer], for a German flag, [on a] German vessel, the salary will be around $1000, which is equivalent to 50,000 pesos. If he works in the Philippines, he will most likely receive a salary of 7000 pesos. For officers, if you get paid like $4000 a month, if you work there [ashore], you can likely get 15,000-20,000 [pesos] $4000 is like 200,000 pesos a month, it’s a big difference, and that’s without tax. If you work at home [in the Philippines] you get taxed 25% so, the attraction is so [big]. [Roslin, Crew Manager, 38, from the Philippines, interview in English]

As a result of limited choices of alternative employment ashore Filipinos often feel pushed towards the seafaring profession. This happens in other developing countries as well (Sampson and Schroeder 2006; Dearsley 2013; IMF 2015) such as Ghana, Cape Verde, India, Russia and Ukraine. Seafarers from these countries stated that the high wages in the shipping industry meant that jobs ashore could not compete in terms of pay and the promise of a good salary was a significant reason for joining the merchant navy. Wu and Morris (2006) report that at the turn of the century the working lives of employees in China, Former Soviet Union countries and Eastern European countries were heavily affected by ‘instability, job insecurity, an erosion of social welfarism and greatly differentiated wages’ with the result that some individuals were compelled to join the shipping industry (Wu and Morris 2006, p. 43). Similarly, one interviewee from Ukraine revealed:

In childhood, every person fantasises about becoming something, […] but when you become older you start understanding that you have to choose a profession that will bring you money. For us, there are young people that don’t understand that, he [a person] just goes and studies, and eventually, he receives a higher education in some rocket science Institute, he spent a lot of energy, wrote projects, but he works somewhere in a shop, selling cell phones. It happens. A person with higher education, in our country, Ukraine, will sell cell phones in a shop. […] Because there aren’t jobs. Even if there is this kind of job, there are many students… […] You don’t have places to work in. I mean, you have the qualifications but you don’t have a workplace. That’s why, I mean, when I was already applying [to work on board], I didn’t know much about it, that’s why this is not something I might have wanted in life, but I knew that I had to set myself somehow in this life, to earn [enough money]. That’s why I came here [to work on board]. [Mace, Second Engineer, 26, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

The quote indicates the lack of employment opportunities in Ukraine that can push individuals towards employment at sea. It is not exclusively for financial reasons that the choice to become a seafarer is made. Individuals’ geographical origin is also mentioned as another reason for going to sea with physical proximity to the sea being cited as a reason for their career choice (Gould 2010; Østreng 2000; Barnett et al. 2006; Hill 1972). On several occasions during interviews, seafarers mentioned coming from a nautical background with pressure being exerted on them to choose this occupational path by their closest relatives. For instance, Stannis, a chief cook, mentioned:

My family is completely seamens, they are all seafarers. So when I am in […] school, I am thinking we must go to the sea, like that. That time I know. That I have to go there. Because father is a seafarer, uncle seafarer, brother seafarer, mother’s father, mother’s side everybody, where I live in that place, all of them seamen. [Stannis, Chief Cook, 50, from India, interview in English]

In a sense Stannis implied that he had little choice about going to sea given that this was the chosen occupation for so many family members. His career choice was almost inevitable. This emphasises the pressure individuals in sea-going societies can be under when making decisions regarding their future. Influence from families, i.e. pressure or support from partners (Barnett et al. 2006; Baylon and Stevenson 2005; Calderón 2011; Dearsley 2013; Guo et al. 2006) can be significant. For example, one seafarer revealed:

My wife […] she said ‘go and earn money, we need money for the family, we need money for the baby…’ I mean she was already used to, since my first contract, she had my card, I was receiving my salary, from the first contract [she could use my money]. And when I returned from my contract, I needed to stay at home a little bit because there weren’t enough jobs, and then the complaints started. Why don’t we have that, why don’t we have this? And she was already used to getting everything she wanted [not denying herself from anything] and there it was… and is continued going downhill from there. [Will, Third Mate, 36, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

Other seafarers report going to sea because of good career prospects (Barnett et al. 2006; Calderón 2011; De Silva et al. 2011; Baylon and Stevenson 2005; Guo et al. 2006) which may include fast-track promotion opportunities. For example, Captain Edmure described the importance of good career prospects for his choice of occupation. Throughout the interview Edmure mentioned his life-long aspirations to become a seafarer but despite his emotions he described practical motives as playing a significant role in his decision:

When I did my [officer] license, I was still single, after that I got married, so the consideration was, instead of working in several jobs, to work in one job, hoping there was a fast promotion route, and then getting a senior position, at least first mate, and then Captain, and then to see where I can develop from there. Doors close, doors open, but this was the direction. […] It does not mean that now, after eight years that I’ve reached the highest rank, that it means that I have outgrown it. In fact, now I am starting to learn, every day, in every port, you learn something that you did not know before. It is endless, this experience. To leave this area? No way. I will be doing something that relates to [the sea] for the rest of my life. [Edmure, Captain, 48, from Israel, interview in Hebrew]

In contrast to what might be termed ‘aspirational reasons’ for going to sea, sometimes it was the lack of an aspiration or goal that resulted in an individual joining the occupation. Many seafarers mentioned arbitrary reasons for joining seafaring, and those reasons were mostly associated with what they referred to as ‘luck’, ‘chance’, and ‘fate’. Seafarers in the study mentioned that they did not have a specific plan to work at sea when they were young, but they happened to ‘stumble upon’ their job at some point during their lives. For instance, Renly, administrative officer, said:

[My friend] was doing a cadet course in the [Maritime] Academy, and he told me that there is a course for the job I am doing right now, and I can apply. That is how I got to know about the seamen’s life and all this. So I did four years training in the Academy. […] [In high school] I had no idea about any kind of, like sea work, about working at sea, I had no plans like nothing, no plans for future, I just, doing my study, and whatever happens, happens. Just go with the flow, enjoy that. [Renly, Administrative Officer, 27, from India, interview in English]

Renly’s work on the ship seems to be an almost coincidental occurrence, as he did not plan on becoming a seafarer before the encounter with his friend. Similar stories were uncovered by Sampson and Schroeder (2006) in their research with migrants to Germany. Others expressed the adventurous nature of working at sea as a main attraction to join and stay in this occupation (Barnett et al. 2006; Gould 2010; Hill 1972; Mack 2007; Baylon and Stevenson 2005; Dearsley 2013; Seaways2014). These reasons might be interpreted as somewhat whimsical choices with seafarers describing no particular plans for a long-term future and consequently ultimately abandoning the seafaring occupation.

Leaving the Sea: Attrition Influences

Those seafarers who have no intention of staying and developing a ‘career’ in the shipping industry may leave the industry after several years. Some treat seafaring as a passing phase in their lives and, when they first join the occupation, their intention is to work for a short period until they have earned enough money to achieve certain set objectives (Barnett et al. 2006; Klikauer and Morris 2003; Dearsley 2013). For example, one Chief Mate revealed:

[Seafarers] came [to work on a ship] for a short time to earn some money, like the Dutch people call it “quick money”, so they joined to get “quick money”. To earn money quickly and that’s it, and later on, those people in the company will move forward, to something more constructive and interesting, they might open up a business, perhaps something else, but in any case, they don’t return [to the company or to seafaring]. [Oberyn, Chief Mate, 40, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

Thus, after several years during which they put aside money, they are ready to leave, to fulfil their plan to search for a different job ashore. In many cases seafarers wish to get to the ‘top’ of the career ladder at sea and work as a chief engineer or captain and then leave. In other cases, the opportunity to gain transferable skills that an individual can use for positions ashore is also mentioned. For instance, the prospect of a good career path was an evident attraction for Varys, a trainee cook:

I was working in the kitchen [ashore], and I saw the chefs, how much respect they got, how [many] skills, you know, they were able to present. So, I was very, you know, fascinated about this. So when, it was a time when, [it was] hard to select a particular field, so I told my father, like okay, this is what I want to do [cooking], but, not on land, you know? Not on shore. I want to work in sea. […] [A]shore, [in] one year I cannot become a chief cook or… you know, because there are a lot more people waiting. And here [on board] I become a chief cook in one year, even [in] less [time]. [Varys, Trainee Chief Cook, 23, from India, interview in English]

Varys perceived work at sea as his way forward to a more challenging job ashore. He regarded his work as a ship’s cook as the quickest way for him to learn and gain the skills needed for opening his own restaurant ashore. In this example Varys believed that working at sea would help him develop a professional identity as a ‘chef’, not as a seafarer. He believed that he would be able to acquire transferable skills at sea that he would be able to apply for employment ashore, one of the characteristics of the ‘portfolio career’ as described by a few authors (Arthur 1994; Cohen and Mallon 1999; Mallon 1998; Platman 2004).

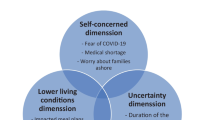

Another reason for leaving could be seafarers’ failure to cope with the strenuous conditions of work on board. These include the cultural differences, the small crews, the constant stress and high workloads (Barnett et al. 2006; Slišković and Penezić 2017). The following example of a seafarer’s intention to leave is illustrative:

[I’m planning to work] maybe another five years more. Until I’m like 40 years old. I will stay at sea [and then leave]. […] Because I think about the health side, this is a hectic job, especially as a marine engineer, compared to navigation side, engineering side is more tough. […] Because we’re working in heat, engine room is always above 40°C, 45°C, and the vibration, a lot of things. So it’s better to quit at the age of 45, if I can make enough money, then I would think of something else. [Aegon, Second Engineer, 31, from India, interview in English]

In addition a general lack of physical and mental preparation for shipboard life (Ervin et al. 2002; Fei et al. 2012; Gekara 2009; Guo et al. 2006; Hill 1972) may cause many individuals to leave after a few contracts. Some colleges and institutions for seagoing officers still present a romanticised view of seafaring in their advertisements, promising individuals a ‘unique opportunity’ to ‘travel the world’ and develop a ‘successful career’ with job opportunities ashore. In reality however, seafarers are constantly pressurised to return to the ship when in port (Sampson 2013; Kahveci 2007a, b) and the number of positions available ashore for sea-going personnel are limited (Pettit et al. 2005; Barnett et al. 2006; Gardner et al. 2007). The romanticised view seems to influence some individuals since they join the shipping industry and work there for many years. Others find the reality of shipboard life negative with the romantic illusion shattered once they start working on the ship, and they are likely to leave after a short period of time.

In other cases, the influence of a seafarer’s family can be behind a decision to leave the seafaring occupation. For example, some seafarers are pressurised by their families to change to a shore-based job due to the demanding nature of work at sea and the, associated, long periods of absence from their homes (Barnett et al. 2006; Calderón 2011; Ervin et al. 2002; Thomas 2003). Changes in domestic circumstances (Dearsley 2013) can also lead to a need to leave seafaring. For example, Lancel, an electrician weighing up whether to work at sea or not, predicted:

My family, I don’t know, if I get married, I will have children, yes, it will affect my decision [whether to join the shipping industry or not], [if] it will damage my family, I will be looking for something else. [Lancel, Electrician, 24, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

Despite the fact that in many cases seafarers successfully combine their occupation and their family life (Thomas et al. 2001; Thomas 2003), it is not always perceived as possible as Lancel’s example shows. For others, low pay in relation to the sacrifices they make (Dearsley 2013; Calderón 2011; Gerstenberger 2002) plays a significant part in their decision to leave and seek less demanding occupations ashore. Despite being paid much less they are able to spend more time with their families and work in less arduous conditions. Some seafarers, especially seafarers in low-demand positions like junior officers and ratings (where supply often outstrips demand), find that the lack of employment opportunities in the shipping industry causes them to search for alternative employment opportunities ashore (Barnett et al. 2006; Fei et al. 2012; Gould 2010; Mack 2007; Ervin et al. 2002; Seaways2014). Many junior officers in the research complained about the lack of employment options at sea. One officer revealed:

[Seafarers need to wait for the next contract] because there’s this thing, too much of, many people are like fourth engineers, too many fourth engineers are there, so they [crewing agencies] cannot give job to everybody, too much of waiting, [for] fourth engineers especially. [Jon, Fourth Engineer, 25, from India, interview in English]

Jon indicated the difficulties he had had in securing a contract at sea due to an over-supply of seafarers holding a similar role. In the same way another officer explained:

In my first year [of studies] we were 700 [cadets] in my university, 700 people, and we finished around 250. Most of them, they quit because they found out that there is no way to go on sea as a cadet, so no point to lose four years for nothing. Most of them they finished, but there is no chance, they didn’t have any chance [to find a job at sea], so they are working either in harbour, or in [the] office, in some small companies, depends on their luck of course. [Dontos, Second Mate, 27, from Romania, interview in English]

Dontos implied that some people leave seafaring during their training because of the lack of career prospects in the industry and difficulties in finding a job. Just as good career prospects were cited as a motivation for going to sea so too were they given as a reason for staying at sea for a limited period of time (Baylon and Stevenson 2005; Calderón 2011; Barnett et al. 2006; Guo et al. 2006). When interviewed, both formally and informally, many seafarers talked about wanting to stay at sea for just a fixed length of time for example ‘for ten years’ or ‘until I get my captain’s ticket’, and then continue their ‘career’ ashore. The following quote is illustrative:

[Seafaring is] not a job for life. I will never work in one place for the rest of my life [laughing] […] I don’t like working in one place all the time, because after a certain time, everything repeats itself, everything will be standard, you also have to progress. […] I want to see new things. That’s what life is about, not to be stuck in the same place all the time, in the same company, in the same factory, in the same table in the same office, you always have to see new things. [Walder, Electrician, 27, from Israel, interview in Hebrew]

Nevertheless there are seafarers who continue to work at sea long-term, whether they originally planned to do so or not.

Staying at Sea: Retention Factors

Despite their intentions to leave and pursue a different career, several seafarers in my research indicated that somehow they had got ‘stuck’ on board. This is sometimes described as the phenomenon of ‘golden handcuffs’ whereby seafarers become accustomed to higher incomes that cannot usually be earnt elsewhere. One of the interviewees put it this way:

[Being a seafarer] it’s like this weakness, […] it’s like [being] a drug addict, you know? Someone who got used to drugs, and says ‘well that’s it, this is the last time…’ and after that, ‘I need to feel good’, he feels the craving, he needs a particular dose of drugs to ease the craving, and once he gets off, he says ‘that’s it, that was the last time and I will not do that anymore’. And afterwards when he starts to feel the craving again, again he runs after this dose. The same happens with seafarers, the same. When the money finishes, do you understand? And he got used to living in luxury, he has gotten used to [spending large amounts of money], where would he go? With his education, he cannot earn anything at home, I mean what’s next? You go to sea… you have to. And this way, every voyage it’s like the last, that’s why… I’m attracted to this profession. […] [The seafarer] has already gotten used to not denying anything from himself, for instance he got used to, there is a new phone model that came out, he can just go and buy it. Just because he has a sufficient salary, […] if I want to buy a phone for $400, I just go and buy it, without problems. But at home, with a salary of $200, $300, I will not be able to afford this. [Will, Third Mate, 36, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

The difficulty in leaving the sea can also be as a result of adapting to the shipboard way of life and environment which whilst frequently disagreeable nevertheless makes settling ashore hard. For example, Tywin, motorman, describes how:

I wake up, and after 15 minutes, I descend two levels, and I am at work already. I know that [when] I arrive [on board], I get fed, I’m always warm, I don’t need to pay for water, I don’t need to pay for bills, I don’t need to cook. […] But at home, [when] I come [home], I lose weight straightaway, [laughing], during the contract I always gain weight, [but when] at home I lose weight straightaway because I eat only once a day, it just happens this way. Plus, [at home] you have all these domestic problems, you need to pay for energy, for water, going there and there, you have a queue there, [stand in] a queue there, you’re not used to that anymore. [Laughing] so it becomes hard in some way [to come ashore]. [Tywin, Motorman, 27, from Ukraine, interview in Russian]

Tywin describes the provision of basic needs on board that were not provided ashore, explaining how he had become too used to the institutionalised life at sea. There were similar statements from interviewees who felt unable to cope with the ship to shore transition that they had always imagined making. One Chief Engineer described how:

If until the age of 35 a person could not separate himself from the sea, then he will not be able to do that for the rest of his life. For many reasons, I tried, about twice, once I worked for a year ashore the second time even more […] seafarers can work only at sea. Ashore I could find a job with reasonable pay, […] it didn’t work out. I could spend time ashore, I was searching and searching and searching, but when […] you get countless offers to work at sea, to get paid twice as much, but it is at sea, [laughing] and you also have the documents you need in order to work, to take care of all these issues, of course you will choose [seafaring], [uses an expression in Russian] “better one bird in the hand than two birds in the bush”, so after that, the point of [working ashore] was lost. […] This is it. So long as my health is good enough, I hope it is enough until retirement to continue. [Sandor, Chief Engineer, 49, from Russia, interview in Russian]

Sandor emphasized the golden handcuffs that he found himself ‘wearing’, however his account also endorsed the view that once acculturated to sea-life seafarers can ‘only work at sea’. This resonates with accounts stressing the ‘addictive’ nature of working at sea, mentioned by Heen (1988) and Hill (1972), which often complicates any attempts to transfer ashore from a sea-based job and consequently transforms seafaring into a life-long occupation.

Conclusion

The nature of work at sea is different from that of employment ashore due to the intensive and all-consuming work environment on ships and the long absences from families and friends while seafarers are on board. In the light of this, this chapter focused on some of the factors which influence an individual into making seafaring a choice of occupation, on circumstances of retention that predispose a seafarer to remain and on influences of attrition that may ultimately affect a seafarer’s decisions to leave the sea. The reasons behind an individual’s decision to work at sea are varied. A common motivation in going to sea is money, another is the lack of local employment opportunities and a third is pressure from family and friends. In addition some seafarers may wish to develop their skills at sea, in order to pursue a ‘portfolio career’. Others may plan to enter seafaring as a temporary strategy but remain because they have become institutionalised.

A challenging career development route exists. On the one hand individuals face contract-based (temporary) employment and on the other hand may have ambitions for promotion. In most cases, there is no commitment on either side (employer or employee) to remain with the same company. Despite this challenge, however, many individuals often remain and work at sea for the rest of their lives. Even though it can last over the whole period of an individual’s employment, this lifelong work does not generally follow the traditional trajectory that characterises a ‘career’. In bureaucratic employment practices individuals have job security and can expect employment for the rest of their lives. This is generally with a single employer. In the precarious shipping industry, seafarers’ employment is not guaranteed, and they often feel that they are ‘stuck’ at sea with few options to work elsewhere. While some seafarers remain at sea for the rest of their working lives other seafarers develop a ‘portfolio career’. They treat seafaring as a stop along the way and use it as leverage to improve their employment options in the global labour market where they intend to continue their employment across different organisations and across different industries.

By utilising flexible employment practices, shipping companies have appeared to enjoy the best of both worlds, having seafarers available for employment when required and at the same time retaining the option to shed them when it is necessary. However seafarers who develop a ‘portfolio career’ intend to engage with seafaring as a temporary job and are very likely to leave the sea after several years of employment. Consequently shipping companies might not be able to rely on a ready supply of seafarers. In the future the lack of commitment by both the employer and the employee to a permanent employment contract could well create supply problems across the industry.

Notes

- 1.

The mentioned project is a PhD thesis at Cardiff University, funded by the Nippon Foundation and the Seafarers’ International Research Centre (SIRC), entitled “Careers and Labour Market Flexibility in Global Industries: The Case of Seafarers”. The thesis was published in 2018 and is available online: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/109438/.

References

Acejo, I. 2012. Seafarers and Transnationalism: Ways of Belongingness Ashore and Aboard. Journal of Intercultural Studies 33 (1): 69–84.

Alderton, T., M. Bloor, E. Kahveci, et al. 2004. The Global Seafarer: Living and Working Conditions in a Globalized Industry. Geneve: International Labour Office.

Arthur, M.B. 1994. The Boundaryless Career: A New Perspective for Organizational Inquiry. Journal of Organizational Behavior 15 (4): 295–306.

Barnett, M., D. Gatfield, B. Overgaard, et al. 2006. Barriers to Progress or Windows of Opportunity? A Study in Career Path Mapping in the Maritime Industries. WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs 5 (2): 127–142.

Baruch, Y. 2006. Career Development in Organizations and Beyond: Balancing Traditional and Contemporary Viewpoints. Human Resource Management Review 16 (2): 125–138.

Baruch, Y., and M. Peiperl. 2000. Career Management Practices: An Empirical Survey and Implications. Human Resource Management 39 (4): 347–366.

Baum-Talmor, P. 2012. From Sea to Shore: An Ethnographic Account of Seafaring Experience (in Hebrew). M.A. Dissertation [Unpublished], Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Haifa.

———. 2018. Careers and Labour Market Flexibility in Global Industries: The Case of Seafarers. PhD Thesis, SIRC, Cardiff University.

Baylon, A.M., and C. Stevenson. 2005. Aspirations of Filipino Cadets vis-à-vis UK Cadets. Proceedings of the 6th LSM Conference. Manila, Philippines.

Belousov, K., T. Horlick-Jones, M. Bloor, et al. 2007. Any Port in a Storm: Fieldwork Difficulties in Dangerous and Crisis-Ridden Settings. Qualitative Research 7 (2): 155–175.

BIMCO. 2005. Manpower 2005 Update: The Worldwide Demand for and Supply of Seafarers. Warwick: Warwick Institute for Employment Research.

———. 2010. Manpower 2010 Update: The Worldwide Demand for and Supply of Seafarers. Warwick: Warwick Institute for Employment Research.

———. 2015. Manpower 2015 Update: The Worldwide Demand for and Supply of Seafarers. London: Maritime International Secretariat Services Limited.

Bloor, M., and H. Sampson. 2009. Regulatory Enforcement of Labour Standards in an Outsourcing Globalized Industry the Case of the Shipping Industry. Work, Employment & Society 23 (4): 711–726.

Brown, P. 1995. Cultural Capital and Social Exclusion: Some Observations on Recent Trends in Education, Employment and the Labour Market. Work, Employment & Society 9 (1): 29–51.

Burgess, J. 1997. The Flexible Firm and the Growth of Non-standard Employment. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 7 (3): 85–102.

Calderón, M.V. 2011. Seafarers in Ecuador: A Labour Market Study (A Labour Market Project Undertaken by the Seafarers International Research Centre (SIRC) in Collaboration with the Pontificia Javeriana University of Colombia). Cardiff: SIRC.

Cohen, L., and M. Mallon. 1999. The Transition from Organisational Employment to Portfolio Working: Perceptions of Boundarylessness’. Work, Employment & Society 13 (2): 329–352.

De Silva, R., P. Stanton, and J. Stanton. 2011. Determinants of Indian Sub-Continent Officer-Seafarer Retention in the Shipping Industry. Maritime Policy & Management 38 (6): 633–644.

Dearsley, D. 2013. Maritime Career Path Mapping 2013 Update. Europe: European Community Shipowners’ Associations (ECSA) and the European Transport Workers’ Federation (ETF).

Ervin, A., G. Flores-Macias, H. Lee, et al. 2002. Reducing Attrition at the Cadet Training Academy. Durham: Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, Duke University.

Fei, J. 2011. An Empirical Study of the Role of Information Technology in Effective Knowledge Transfer in the Shipping Industry. Maritime Policy & Management 38 (4): 347–367.

Fei, J., J. Lu, and F. Kow. 2012. Identifying the Factors Affecting Active Seafaring Career. 1st Annual World Congress of Ocean 2012. Dalian, China, 1.

Gardner, B., P. Marlow, M. Naim, et al. 2007. The Policy Implications of Market Failure for the Land-Based Jobs Market for British Seafarers. Marine Policy 31 (2): 117–124.

Gekara, V. 2009. Understanding Attrition in UK Maritime Education and Training. Globalisation, Societies and Education 7 (2): 217–232.

Gerstenberger, H. 2002. Cost Elements with a Soul. Proceedings of International Association of Maritime Economists-International Conference, Panama, 13–15 November.

Glen, D., and J. McConville. 2001. Employment Characteristics of UK Seafaring Officers in 1999. Marine Policy 25 (3): 215–221.

Gould, E.A. 2010. Towards a Total Occupation: A Study of UK Merchant Navy Officer Cadetship. PhD Thesis, SIRC, Cardiff University.

———. 2011. Personalities, Policies, and the Training of Officer Cadets. SIRC Symposium Proceedings, Cardiff University.

Guo, J.L., G.S. Liang, and K.D. Ye. 2006. An Influence Model in Seafaring Choice for Taiwan Navigation Students. Maritime Policy & Management 33 (4): 403–421.

Heen, K. 1988. Norwegian Fishermen: Labour Market Behaviour and Analysis. Marine Policy 12 (4): 396–407.

Hill, J.M.M. 1972. The Seafaring Career: A Study of the Forces Affecting Joining, Serving and Leaving the Merchant Navy. London: Tavistock Institute of Human Relations.

ILO. 2015. World Employment and Social Outlook: The Changing Nature of Jobs. Geneva: International Labour Office.

———. 2019. World Employment and Social Outlook. Geneva: International Labour Office.

IMF. 2015. World Economic Outlook: Uneven Growth Short- and Long-Term Factors (A Report by the International Monetary Fund). Washington: International Monetary Fund.

———. 2019. World Economic Outlook, October 2019: Global Manufacturing Downturn, Rising Trade Barriers. Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Kahveci, E. 2007a. Reviewing Seafarers’ Welfare at Sea and Ashore. The Sea, London: Mission to Seafarers (186 Mar/Apr), p. 4.

———. 2007b. Welfare Services for Seafarers. SIRC Symposium Proceedings., Cardiff University, p. 10, ISBN 1-900174-31-6.

Klikauer, T., and R. Morris. 2002. Kiribati Seafarers and German Container Shipping. Maritime Policy & Management 29 (1): 93–101.

———. 2003. Human Resources in the German Maritime Industries: ‘Back-Sourcing’ and Ship Management. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 14 (4): 544–558.

Mack, K. 2007. When Seafaring Is (Or Was) a Calling: Norwegian Seafarers’ Career Experiences. Maritime Policy & Management 34 (4): 347–358.

Mallon, M. 1998. The Portfolio Career: Pushed or Pulled to it? Personnel Review 27 (5): 361–377.

Østreng, D. 2000. Sailors - Cosmopolitans or Locals? Occupational Identity of Sailors on Ships in International Trade. Vestfold College Publication Series/Paper: 1–20.

Pettit, S.J., B.M. Gardner, P.B. Marlow, et al. 2005. Ex-seafarers Shore-Based Employment: The Current UK Situation. Marine Policy 29 (6): 521–531.

Platman, K. 2004. ‘Portfolio Careers’ and the Search for Flexibility in Later Life. Work, Employment & Society 18 (3): 573–599.

Sampson, H. 2013. International Seafarers and Transnationalism in the Twenty-First Century. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Sampson, H., and T. Schroeder. 2006. In the Wake of the Wave: Globalization, Networks, and the Experiences of Transmigrant Seafarers in Northern Germany. Global Networks 6 (1): 61–80.

Sampson, H., and L. Tang. 2015. Strange Things Happen at Sea: Training and New Technology in a Multi-Billion Global Industry. Journal of Education and Work 29 (8): 1–15.

Seaways. 2014. Seafarer Survey - Why Sail? Seaways - The Nautical Institute Magazine, March 2014 Issue, p. 10.

Slišković, A., and Z. Penezić. 2017. Lifestyle Factors in Croatian Seafarers as Relating to Health and Stress on Board. Work 56 (3): 371–380.

Stone, K.V.W. 2005. Flexibilization, Globalization, and Privatization: The Three Challenges to Labor Rights in Our Time. Osgoode Hall Law Journal UCLA School of Law Research Paper No. 05–19: Public Law & Legal Theory Research Paper Series.

Thomas, M. 2003. Lost at Sea and Lost at Home: The Predicament of Seafaring Families. Cardiff: SIRC.

Thomas, M., H. Sampson, and M. Zhao. 2001. Behind the Scenes: Seafaring and Family Life. SIRC Symposium Proceedings, Cardiff University, June, ISBN 1-900174-16-2.

Wu, B., and J. Morris. 2006. ‘A Life on the Ocean Wave’: The ‘Post-socialist’ Careers of Chinese, Russian and Eastern European Seafarers. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 17 (1): 25–48.

Zurcher, L.A. 1965. The Sailor Aboard Ship: A Study of Role Behavior in a Total Institution. Social Forces 43 (3): 389–400.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Baum-Talmor, P. (2021). Careers at Sea: Exploring Seafarer Motivations and Aspirations. In: Gekara, V.O., Sampson, H. (eds) The World of the Seafarer. WMU Studies in Maritime Affairs, vol 9. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49825-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49825-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-49824-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-49825-2

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)