Abstract

Human resource (HR) management has been proposed as being one of the core drivers of the modernization of the public sector, in particular with reference to the changing nature of people management and ‘HR-public service partnerships’ as an antecedent capacity of modernizing public service organizations. Notwithstanding the ongoing interest in the transformation of HR systems, this study explores how and why such relationships between HR management (HRM) and organizational change emerge. Considering a resource and capability-based approach, the analysis reveals strategic HRM practices as a useful concept to distinguish HR activities and the processes that are occurring when a HR strategy is performed. Moreover, using a multiple case study design, the study exhibits the antecedents and effects of HR strategy formation during accounting change in six German local governments. The results provide evidence that forces of either strategic or administrative patterns of alignment refer to different layers and the sequencing of HRM activities within a process of HR system change, thereby revealing the possibility of contradictory effects induced by HR change agency on either the ‘HR’ or the ‘public service’ side of the strategic coin.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Human resource (HR) management has been proposed as being one of the core drivers of the modernization of the public sector (Pollit and Bouckaert 2004: 67; Boyne 2003). For instance, within the public management literature it is commonly accepted that public service organizations can potentially improve their performance by strengthening their HR management (HRM) (Selden 2009: 179 et seq.; Carmeli and Schaubroeck 2005). Current strands of research focused the changing nature of people management in the modern public sector (Truss 2009a; Harris 2002) and proposed ‘HR–public service partnerships’ as an antecedent factor of modernizing public service organizations (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Bach and Kessler 2007). Notwithstanding the interest in the transformation of HR systems, only a few studies have explored how and why such relationships between HRM and organizational change have emerged despite the risk that HR role ambiguity and vicious circles tend to limit the possibilities of HR strategy formation (Guest and King 2004; Legge 1978: 66 et seq.). Due to the acknowledged significance, research has to reveal more about HRM and its place at the centers of decision-making in public service organizations. One main premise is that the link between HRM and organizational change interventions aiming to improve public service delivery is best explained through a strategy-based (public) management approach, a position also consistent with strategic HRM scholarship. This paper refers to a resource and capability-driven approach in order to investigate the changing HRM role and how it is assigned to strategic change and performance in public service organizations. The analysis used a multiple case study design to distinguish the formation of HR strategies during accounting change, which is claimed as one of the most significant and enduring challenges in modernizing public service delivery. In particular, replicating processes of HR strategy formation in six German municipalities reveals further insights into factors contributing to why some local governments fail to develop HR strategies in coping with institutional pressures on HR development (HRD), whereas others do not.

The article is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, the concept of strategic HRM in public service organizations is reviewed as a two-level and sequential phenomenon in order to comprehend its effects as a source of HRD and public service improvement. The remaining sections introduce concept development (Sect. 3), the research design (Sect. 4) and thereafter present the outcomes of data analysis (Sect. 5). Finally, conceptual implications of the findings are discussed (Sect. 6) and summarized in the conclusions (Sect. 7). The Appendix outlines further details regarding the research setting and data analysis.

2 Changing the nature of public HR management

HRM has been proposed as one of the core drivers of organizational change and renewal in the public sector and a crucial concept in improving the performance of public service delivery in local government (Pollit and Bouckaert 2004: 74 et seq.; Ingraham 2007; Maddock 2002). As exhibited in Fig. 1, it is commonly accepted that local governments can potentially derive valuable organizational outcomes in terms of efficiency gains or public service improvements when their HR policies and practices strengthen a sustainable HRD. It is also assumed that the distinct value of the HR stock is reinforced by a (strategic) HR system, especially with regard to the organizational level aggregate of individual knowledge accumulation, service orientation and value commitment (Ployhart et al. 2009; Selden 2009: 13 et seq.; Carmeli and Schaubroeck 2005).

The proposition can be traced back to competing perspectives on public HRM. Regularly, a personnel system-approach has been appreciated positively as ‘model employer’ with regard to dominant values of a civil service HR system in terms of functionalism, paternalism, individual rights, and social equity. Under the recent reform agenda, a managing people as resources-approach refers to external or internal forces that aim to induce essential shifts in public service delivery, e.g., decentralization, privatization or public–private partnerships. This approach seems to replace the traditional one by emphasizing HRD as an asset to achieve higher levels of value for the citizenry and in order to develop and sustain the required governmental capabilities (Bach and Kessler 2007; Llorens and Battaglio 2010; Harris 2005). Subsequently, this stream of research identifies effectiveness of the HR system as one of the critical factors to sustain valuable outcomes, including the demand to become more strategic in its roles, and flexible and responsive in its policies and programs (Perry 2010; Lonti and Verma 2003). The conceptual implications are twofold. First, as Hays and Kearney (2001) stated, HR systems by themselves are subjected to a fundamental transition in their operating practices, which embodies a range of opportunities as well as daunting pressures on replacing the established ones (Truss 2009a; Teo and Rodwell 2007). Additionally, it should be considered that changing HR systems is proposed as an antecedent capacity to leverage institutional pressures to the distinctive value of people, in particular to enhance the knowledge stock to cope with the challenges of public service improvements (Carmeli and Schaubroeck 2005; Brown 2004). Thereby, the logic of leveraging stresses the paradoxical nature of changing the HRM role, as it emphasizes organizational tensions between performance effects of a strategic HR system, in particular when a portfolio of sustainable resource investments is required, as well as the risk of failure in recognizing complementarity and the co-evolution of HR strategy and organizational change (Kepes and Delery 2007; Smith and Lewis 2011).

One main premise is the notion that distinct outcomes of modernizing public HRM are best explained through a strategic approach (Perry 2010; Selden 2009: 3), a position consistent with recent perspectives in strategic HRM scholarship (Ridder et al. 2012a; Snell et al. 2001). Additionally, this stream of research suggests that switching the terminology from ‘people’ to ‘human resources’ reflects a conceptual reorientation extending the focus from a person–job fit-approach at the individual level to the distinct value of the HR stock at the organizational level of analysis, mainly with references to the resource-based view (Snell et al. 2001; Ployhart et al. 2009). Within a tenet of viewing people as assets for organizational change, recent studies on changing HRM in public sector organizations primarily focus on topics of evolutionary fitness (Helfat et al. 2007: 7 et seq.): the institutional pressure to adopt HR concepts similar to the business sector, partly enforced by legal regulations (Pichault 2007; Hays and Kearney 2001), the opportunity and threats to develop strategic HRM roles and effective HR policies and practices (Harris 2002, 2005; Truss 2008), both coupled with a discussion whether a strategic HR approach contributes to managing modernization (Currie and Procter 2001; Alfes et al. 2010) and improving the value of public service delivery (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Ridder et al. 2012b).

Despite such interest, only a few studies have explored how and why sequential effects between institutional pressures, HR (stock) development and organizational change occur. While much of the prescriptive literature has advocated the strategic HRM role (Truss 2009a; Ulrich 1998), the evidence concerning the degree of implementation or effectiveness in public service organizations suggests more complex and partly contradictory effects of HRM-based reforms. For example, the role enacted by HR departments in local government is usually described as administrative or reactive, primarily constrained by lack of resources and minor involvement in organizational decision-making (Jaconelli and Sheffield 2000; Harris 2005; Auluck 2006). In the case of becoming more strategic, in particular by decentralizing and transferring HR responsibilities to line management, HR departments are partly valued given their professionalism and operational involvement (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Truss 2008). But, the recommended inclusion of senior HR managers into strategic decision-making does not seem to have further impacts on strategic integration and the outcome state of HRM activities (Teo and Rodwell 2007).

Furthermore, the studies commonly suggest that the counterpart, e.g., chief executives or senior line managers responsible for governmental capability development that creates value for the citizenry, represents the ‘business role’, putting pressure on HRM becoming more proactive. However, why could it be expected that the so-called street-level activities are inherently strategic and co-evolve, i.e., that they adopt common HR policies or programs on behalf of an organizational or public service strategy (Clardy 2008; Truss and Gill 2009)? As some of the studies show, we need to account for two interrelated subjects: first, for the multiplicity of perceptions about how to build a strategic HRM in public service organizations (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Pichault 2007); and second, for relational issues concerning how a strategically positioned HRM may be linked into organizational change interventions, for example to successfully execute the role of HR change agency (Alfes et al. 2010; Clardy 2008). Thus, the critical issue seems to be the capacity to assimilate or align HR policies and practices at both sides of the strategic coin—not adopting at all or copying the best practices to modernize the public HRM (Pichault 2007; Teo and Rodwell 2007). Even if the strategic HRM role or capacity is identified, considering a logic model emphasizes the link by which a possibly strategically positioned HRM is related to both its antecedents and subsequent effects at the organizational level of strategic decision-making and change as a more complex cause–effect pattern. Accordingly, the proposed link needs to be uncovered as a sequenced chain of events which regularly unfolds over an extended period of time (Yin 2009: 149; Whetten 2009).

If the preceding analysis presents a picture of what might be achieved by changing the nature of HRM in public service organizations, research has to reveal more about the strategic HRM role and its impact on managing organizational change and renewal. Following Tyson (1997), the concept of HR strategy formation refers to the process by which an organization aims to develop its HR stock to enhance organizational outcomes. Gaining further insights from a strategic HRM perspective (Ridder and McCandless 2010; Snell et al. 2001), the concept emphasizes both the distinctive value of HRD—in terms of the immediate outcome of (strategic) HRM activities that varies HR-related opportunities to enhance governmental capabilities—and HR strategy formation as the antecedent capacity to purposefully execute the (strategic) HRM role in at least a minimally acceptable and repeatable manner in order to align the HR system architecture within a process of organizational change (Helfat and Peteraf 2003; Helfat et al. 2007: 5).

As a result, research on (public) HRM needs conceptual frameworks in which the logic model between institutional pressures, the changing state of the HR system and its effects on capability development in public service delivery is acknowledged when exploring how and why processes of HR strategy formation emerge. This article aims to examine both the ‘distinctive value of HRD’ and ‘HR strategy formation’-effects within a context of accounting change in German local governments, and the primary concern is to further explain what leads to beneficial outcome states of HRM activities, stated in terms of changing and aligning the associated HR policies and practices.

Introducing accrual-based accounting in local governments is claimed to be both an innovative and radical change, as it is essentially divergent from former accounting systems (Lapsley 1999; Pollitt and Bouckaert 2004: 67 et seq.). Moreover, replacing the accounting basis is assumed to be a ‘high-impact system’ because of its crucial role in modifying organizational structures, identities and practices throughout the entire organization (Liguori 2012; Bruns 2013). One main premise is that accounting change incorporates more than simply re-designing accounting systems or formal structures of management control. The challenge of accrual-based accounting introduction covers an essential shift in the entire knowledge base of a local authority and also the value and beliefs which constitute and legitimate the ‘taken for granted’ behavior in financial and managerial decision-making (Liguori and Steccolini 2012; Ter Bogt 2008). As such, its introduction is a research field that inevitably incorporates the link between institutional pressures and HRD in terms of enhancing the stock of accounting knowledge distributed within the setting of public service units of the entire organization. Moreover, it supports an embedded research design (Yin 2009: 46 et seq.) necessary to analyze the effects of HR strategy formation at an organizational as well as process level of analysis. In Germany, accrual-based accounting change is stimulated by new budget laws, requiring both resource investments and change management activities at the local level to cope with the challenge (Reichard 2003; Ridder et al. 2005). Distinguishing such ‘corporate’ patterns of accounting change offers a context to elaborate on the embedded process level based on two specific research questions:

-

Value of HRD: What patterns of HRD take place when institutional forces induce the modernization of local governments, as in the case of accounting change?

-

HR strategy formation: How and why do (strategic) HRM activities influence the mode of HRD in such circumstances?

Considering a logic model of the antecedents and consequences of strategic (public) HRM, the visual map exhibited in Fig. 1 can be used as an analytic technique for a case-based research strategy to explore the effects of (strategic) HRM, in particular when outcomes emerge by intervention activities located at different levels of analysis (Whetten 2009; Yin 2009: 149 et seq.).

3 Concept exploration: organizational change, HR development, and modernizing in local government

Concepts such as organizational change, strategy formation, HRM and HR systems are well-established in their research fields, and also in public management research. Nevertheless, recent reviews mostly classify them as somewhat ambiguous and complex, mainly because of the heterogeneity of conceptual developments within each field. Accordingly, the design of this study needs to focus on concepts helpful in exploring the process by which a managing people as resources-approach in local governments creates a contribution to achieve organizational outcomes.

As already outlined, such a process study refers to a multi-level and also temporal analysis to capture issues of both the antecedent factors shaping HR strategy formation and short- and long-term performance effects. One specific feature of this type of research is that the units of analysis are taken to change in content and/or activity level over time, thereby indicating the necessity to identify possible measures to capture changing values of first-order variables (Sminia 2009; Doty and Glick 1994). This is essential in explaining how and why the outcome state of any HR strategy had been achieved, and typically diverged from initial intentions, plans, or procedures (Pettigrew et al. 2001). Moreover, considering a resource and capability-driven approach appreciates the relevance of this type of process research at organizational level of analysis, and addresses HR system changes as the outcome state in order to explore whether (strategic) HRM activities make a difference within the entire organization (Ridder et al. 2012a, b).

Consistent with the aforementioned research issues, the following subsections exhibit the core issues of the concept exploration. First, the conceptual scheme of ‘accounting archetypes’ serves the purpose of differentiating the directed outcome state of accrual-based accounting change at the organizational level, in particular outlined as the contextual setting where (strategic) HRM activities occur. Second, the framing develops a more comprehensive approach to distinguishing patterns of (strategic) HR systems, furthermore classified as the dependent construct in the analysis. Finally, the antecedent factors shaping HR strategy formation are identified. From a resource and capability-based view, the complementarity and co-evolution of organizational change interventions and the HRM role are emphasized to uncover sequential outcome states that stress both the (strategic) pattern of HRM activities in place and how it is aligned with the strategic issues of managing a (large system) change, as in the case of accounting change in German local governments.

3.1 Contextual analysis: archetypes of accounting change

Empirical research that seeks to understand how HRM relates to organizational renewal in the public sector needs to be guided by a concept that theorizes the scale, pace and sequencing of change processes, in particular when the case of accounting change is considered (Amis et al. 2004; Liguori and Steccolini 2012; Carlin 2005).

This is termed as the contextual analysis, as it is directed to investigate how exogenous as well as endogenous forces shape the character of (accounting) change processes in public service organizations, and in local governments, respectively. Within research on change and strategy, concepts like path dependency, strategic orientation and dynamic capabilities reflect this relationship (Teece et al. 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). In particular, Greenwood and Hinings (1996) use the concept of organizational archetypes to differentiate how organizational change evolves. While evolutionary change occurs gradually within a dominant archetype, revolutionary change happens rapidly and affects all parts of the organization simultaneously. The degree of change is associated with a sufficient enabling capacity for action combined with either a reformative or competitive pattern of value commitments. Out of the several reasons why organizations might fail to cope with institutional pressures, there are two essential ones: structural inertia (Hannan and Freeman 1977, 1984) and organizational rigidities (Leonard-Barton 1992; Gilbert 2005). Hannan and Freeman (1984) point out that structural inertia relates to the dynamics of political coalitions, the sunk costs of resource investments and the tendency of precedents to become normative standards. Regarding the latter, Leonard-Barton (1992) emphasizes the managerial paradox associated with the rigidities of capability development. Building new organizational forms relates to discrediting the managerial practices traditionally favored, and managing both inhibits the degree of organizational change. Untangling this paradox, Gilbert (2005) distinguishes the structure of inertia into distinct categories. Resource rigidity refers to the failure to make resource investments; whereas, routine rigidity refers to the failure to perform processes and procedures that enable the use of those resource investments.

Recent studies on both HRM-based reforms and accounting change in the public sector substantiate why contextual (Liguori and Steccolini 2012; Pichault 2007; Osborne 1998) and also sequential perspectives (Truss 2009b; Liguori 2012) are helpful for valuing how and why HRM and the comprehensive organizational settings evolve over time. For example, recent research on accounting change in Italian local governments (Liguori and Steccolini 2012; Liguori 2012) emphasizes the relevance to distinguishing the accounting archetype in place, in particular by accentuating the supremacy effect of sequencing change interventions on an either incremental or more radical outcome state. Correspondingly, Truss’ studies (2008, 2009b) on the change of HR functional forms in UK local governments suggest that the role played by one (HR) function is better explained by the isomorphic pressure of contextual factors alongside with strategic choice and social capital as enabling settings of co-evolutionary forces. Thus, strategic enactment and also the temporal dimension are critical in understanding how HR functional roles evolve in a context of organizational change in public service organizations.

Conceptual reflections as well as empirical evidence substantiate not only non-equivalent, but even complementary effects of institutional pressures, and corroborate the initial proposition of idiosyncratic ‘corporate’ accounting changes in local government. The overall patterns of outcomes are predicted as, for example, either an incremental or more radical adjustment of accounting structures and practices. Moreover, the literature indicates the usefulness of clustering the variety in order to distinguish the certain context of HRM activities, mainly based on the above-mentioned categories and mechanisms helpful in characterizing a comprehensive type or pattern of ‘corporate’ accounting change.

3.2 Considering the non-equivalence of outcomes: patterns of (strategic) HR development

The term HRD has different meanings in contemporary literature. For example, Luoma (2000) and others (Clardy 2008; Garavan 2007) differentiate the HRD plans and procedures to enhance an organization’s HR stock, the HRD function among others in the organization, or the certain outcome state of HRD, that is increasing the applicability of employee skills and knowledge to organizational objectives. The resource-based view adds a somewhat different approach. Strategic HRD is characterized by assessing the HR stock as well as knowledge in and outflows as internal sources related to organizational capability development that is necessary to carry out a value-creating strategy (Dierickx and Cool 1989; Ployhart et al. 2009).

This strand of research recognizes that organizational outcomes can only be achieved if organizational members representing the most relevant HR stock individually and collectively choose to engage in behavior that benefits the organization, in particular in terms of their knowledge and value commitment. First, the HR stock is seen as the carrier of knowledge, attitudes or skills necessary to maintain an organizational strategy, not its outcomes (Bowen and Ostroff 2004; Ployhart et al. 2009). Second, distinctive organizational capabilities are made up out of HR behavior embedded into formal structures and social relationships. Thus, the term knowledge flow refers to the effects of HR systems on the individual level (human capital), but also organizational effects in terms of changing knowledge shared within groups or networks (social capital) or institutionalized within formal rules or procedures (organizational capital) (Kang et al. 2007). Third, if pressures to change are assumed, developing the HR stock relates to the pattern of (strategic) HR policies and practices, particularly in terms of internal alignment and mutually reinforcing effects of such processes, rather than to simply set out some sub-functional activities, such as staffing, training or compensation (Kepes and Delery 2007).

Moreover, Nyberg and Ployhart (2013) recently emphasized that the strategic risk at issue is the erosion of the valuable HR stock, and whether the HR system offsets the effects due to HR depletion that possibly weakens capability performance. Bowen and Ostroff (2004) introduced the concept of ‘strength’ of the HR system to point out that the perceived distinctiveness of HR policies and practices derives as a linking mechanism that mediates the capability effects. Correspondingly, Gratton et al. (1999) distinguished the transformational and performance-related cluster of HR systems which both serve to link any strategic risk or resource gap to HR stock development in either a long- or short-term cycle of bundling HR systems. The proposed three-dimensional model of HR strategy supports a criteria-based assessment by adding the action/inaction dimension in terms of the degree to which a HR strategy is enacted or put into practice (Gratton and Truss 2003). This distinction also emphasizes that perhaps some HR policies or systems are not implemented as intended, and those that are in place may be used in terms that differ from initial purposes (Khilji and Wang 2006).

As such, framing both the mediating role and also the non-equivalence of HRD in this way delineates to distinguish first-order concepts that are useful in categorizing the pattern of HRM activities, in particular regarding the strategic risk or ‘resource gap’ and the associated clusters of HR systems. Non-equivalence is indicated by both variability in the strength of the HR system (high/moderate/low) and, possibly, a surpassing level of HRM activities necessary to introduce and/or re-align HR interventions over time. Despite the proposed effect related to strengthening the HR system (Bowen and Ostroff 2004), further analysis of strategic HRD also has to consider the risk of ambiguity in changing the HR system, and its crucial effect on coping with transformational situations, as in the case of ‘corporate’ accounting change. Subsequently, analyzing the state of HRM activities has to account for change issues related to the HRM capacity itself (Perry 2010; Llorens and Battaglio 2010).

3.3 Antecedents and consequences: the process of HR strategy formation

How organizations create a strategic link between organizational aims, HR systems and performance is the cornerstone of strategic HRM research. In their seminal paper, Wright and McMahan (1992) term HR strategy as the pattern of planned HR deployments and activities intended to enable an organization to achieve its goals. In order to categorize such patterns of HR strategy formation, a configurational approach directs attention to two sets of fit or alignments between organizational and HR strategy that suggest sustained performance effects (Delery and Doty 1996; Kepes and Delery 2007):

-

Strategic contingencies and the vertical linkage (or external alignment) in terms of the congruence between organizational goals and a certain pattern of HRD, and

-

The horizontal linkage (or internal alignment) as to the coherence among the bundle of HR practices, e.g., high-commitment or high-performance work systems.

This line of research highlights that the configuration of organizational factors, in terms of the alternative ways in which local governments define their public service domains, and the certain HR systems’ architecture maximize evolutionary fitness, which possibly reflects an effective outcome state (Ridder et al. 2012a; Doty and Glick 1994). Considering such logic of strategic alignment, needs-driven, opportunity-driven and capability-driven approaches are conceptualized as distinct patterns of HRD practices (Luoma 2000). The proposed figure not only differentiates distinct patterns of HRD, but also suggests the opportunity to value each approach differently. Thus, as Clardy (2008) argues, an organization’s HRD strategy has to be valued in terms of the extent to which it refers to specific dimensions of strategy making, e.g., resource investments, level of strategic integration, or performance criteria.

Proposing patterns of strategic alignment in this way stresses the importance of their adjustment to organizational change, and how this effect evolves. As Tyson (1997) points out, the concept of HR strategy may be interpreted either in terms of organizational fit, the variety of HR policies or practices and, accordingly, their successful implementation (Gratton and Truss 2003; Khilji and Wang 2006), or as a process of decision-making and leadership by which the HR strategy is negotiated and combined to pursue organizational aims. Thus, the concept refers to a set of forces that enables or constrains HRD policy changes leading to a unique outcome state in terms of strong or weak HR practices more or less aligned to an organizational strategy (Hendry and Pettigrew 1992; Luoma 2000).

Referring to strategic HRD processes, research is concerned with the services, roles, and contributions that organizational members like senior and line managers or HR executives undertake in the course of strategic alignment (Tyson 1997; Truss 2001). With regard to this issue, the literature commonly refers to the multiple-constituency of HR functional roles, thereby addressing the different status and influence of HR departments (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Farndale and Hope-Hailey 2009). This stream of research distinguishes ‘strategic HRM roles’ associated with the usual degree of involvement in domains of decision-making, as well as ‘administrative HRM roles’ associated with the degree of professionalism in executing HR policies or programs (Ulrich 1998; Truss 2008). Related to the proposed effort to be more strategic in public HRM, recent research suggests that issues to become more strategic do not replace professionalism and the delegation of HRM responsibility to the line (Truss 2009b; Pichault 2007; Teo and Rodwell 2007). Moreover, managing HR functions strategically relates to structural and social relationships that emerge from the level of operational involvement (Truss and Gill 2009). Thus, a strategic HRM role also incorporates a specific form of social capital (and departmental power) as a source to cope with the challenges of HR strategy formation (Farndale and Hope-Hailey 2009).

Additionally and partially distinct from this approach, a resource and capability-based view emphasizes the organizational and managerial routines by which public service organizations cope with the challenges of capability development (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Pablo et al. 2007). Thus, even understanding that structural and social relationships are a source of HRD, public service organizations must still recognize that both the reliability and sequential order of coupling HRM and capability development is a factor moderating organizational outcomes associated with, for example, ‘corporate’ accounting change interventions. This study emphasizes the context of leading accounting change to consider the pluralistic setting and the role of collective leadership in local governments, especially with regard to challenges associated with the distribution of professional knowledge and autonomy (Denis et al. 2001; Bruns 2013), and how formal structures and leadership roles are induced in order to strategize on resource investments and change interventions (Stewart and Kringas 2003; Jones 2002). In this respect, the ‘order of implementation’ (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000: 1116) summarizes the outcome state of change management interventions in order to introduce ‘embedded’ processes of resource investments, and indicates the governance mechanism to coordinate the variety of change interventions in terms of political support, implementation strategy, and the antecedent (formal) structures to create the HR strategic alignment.

In summary, the concepts and relationships discussed within the previous subsections build on the above-mentioned logic model between institutional pressures to enhance public service delivery and the mediating role of (strategic) HR stock development. There is some evidence that organizational benefits depend on a more complex chain of sequential effects, considering the significance of changing the HRM role as a precursor which constitutes a ‘hub’ to change HRD practices in order to facilitate capability developments. Thereby, HR strategy formation refers to the process by which an organization maintains or changes its HR systems’ architecture to enhance organizational outcomes. This is partially different to strategy formulation (or policy making in the public sector) in how an organization intends or plans to develop its resources to some organizational ends. However, research so far has addressed critical issues in either the antecedents of a more strategic HRM role or possible dependent effects of a more or less strategically aligned HR system. This study aims to contribute to this stream of research by exploring the formation of HR strategies that evolve in a context of managing organizational change in local governments, in particular the large system case of accrual-based accounting change. Thus, the study takes a fine-grained look at the antecedents of HR stock development when local governments aim to replace their accounting systems and investigates why HRM in some local authorities is successful acting as an ‘agent of change’, whereas in others it fails to perform strategically.

4 Research design

The purpose of the study can be described as theory elaboration, as the research design is driven by pre-existing concepts related to public HRM and its strategic endeavors (Yin 2009: 127 et seq.; Eisenhardt 1989). Theoretical elaboration is refined especially by a resource and capability-based perspective, in particular to gain and use rival concepts or propositions to explain certain types of outcomes, in terms of the aforementioned patterns of either administrative or strategic HRD (Whetten 2009; Yin 2009: 135). Thus, the research design refers to forms of pattern matching as analytic techniques which allow gaining such insights from the data without denying concepts and relationships that have previously been useful predictions (Eisenhardt 1989). Accordingly, the variables, categories and assessment criteria substantiated by the previous concept exploration are summarized in Table 3 in Appendix.

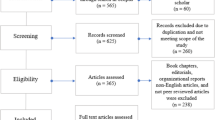

The study used a multiple case research design that supports replication logic to investigate how local governments cope with HR-related challenges of accounting change (Yin 2009: 136 et seq.). The primary unit of analysis covered the patterns of HRD in six German municipalities related to the institutional pressures of a new budget law (‘NKF’) that enforced local authorities to ‘corporate’ accounting change interventions (Budäus et al. 2004; Ridder et al. 2005). The embedded unit referred to their particular capacity to deal with HR-related issues of this organizational change, e.g., the leadership roles as well as structures and routines to configure HR-related processes within the ongoing process. Assuming that conditions may change over time, the analysis was carried out using a temporal bracketing strategy (Langley 1999) to decompose the chronological data into three periods of time, in particular to capture possible alterations of HR-related interventions and the effects of intended and emergent behavior. The details on the research setting and procedures of data analysis are outlined in the Appendix.

5 Analysis of data

The data analysis presented here is based on the logic model of strategic HRD identified in Sect. 2, and considers outcome effects of ‘corporate’ accounting change and the process of HR strategy formation. First, the contextual analysis emphasizes the evidence of comprehensive patterns of ‘corporate’ accounting change. Next, the particular state of HR system changes is demonstrated by stressing the short- and long-term patterns of HR policies and practices. The final section addresses the antecedent factors and provides evidence that opportunities of HRD might be jeopardized not only by one of the sides of the proposed ‘HR-public service partnership’, but also whether and how the relationship occurs.

5.1 Contextual analysis: patterns of ‘corporate’ accrual-based accounting change

First of all, the field analysis confirmed significant non-equivalence according to the patterns of ‘corporate’ accounting change, particularly caused by internal dynamics of the accounting change interventions. This was displayed by both the success and failure of coping with the institutional challenge: the new budget law in charge. Whereas ‘self-evidence’ of accrual-based accounting was, for instance, illustrated by modernization proposals and other archival documents, the study identified the uniqueness of strategy formation and benefits attributed to accrual-based accounting systems, hence the possible outcome effects of a significant shift in the accounting knowledge base. The data indicates, for example, that a purpose to ‘modernize’ was associated with increased resource investments and change management activities. However, the findings also illustrate the tension between a possible prospective stance and the fragility caused by resource rigidities or implementation failures due to less successful project management or the ambiguity of leadership roles.

The contextual analysis aims to explore certain patterns of accounting change at the research sites. An initial summary inspection illustrates noticeable differences in the extent of accounting change with regard to both the value of developing accrual-based accounting systems (prospective, defensive) and the scope of resource investments (technological, organizational, HR) launched for a successful change process. Due to the use of a pattern-matching logic, the data analysis builds on a 3 × 3 Table to substructure the cases (see Table 1; adapted from Bruns 2013; Miles and Huberman 1994: 184).

Table 1 reveals the uniqueness of accounting change in local government, and the possibility to order such cases by analyzing the relationship between the value proposition associated with accrual-based accounting (Boyne and Walker 2004; Liguori and Steccolini 2012) and the current state of accounting change interventions (Lapsley et al. 2003: 57 et seq.; Ter Bogt 2008). Thus, the case ordering ranges from category 1—named as the modernization pattern—to category 2—termed as the professionalization pattern—down to category 3—labeled as the sponsorship pattern (more detailed in Table 5 in Appendix).

-

1.

The ‘modernization’ pattern pursues a strategic agenda characterized by a joint focus on the portfolio of resource investments, which is necessary to enable the modernization of public administration or public service delivery. Accrual-based accounting change is primarily valued as a compelling driving force for introduction (or maintenance) of ‘business’-like financial management systems as an advanced layer to capture prospective scenarios of public service delivery as illustrated, for instance, by the modernization history in Case A. Accrual-based accounting was seen as an essential part of the rationale behind a more comprehensive and outstanding process of modernization:

“The ‘NKF’ is a valuable source of development helping us to step forward in our management capacity”. (Chief Financial Officer, Case F)

“We have the objective to become a service and efficiency-oriented public administration, and ‘NKF’ offers the chance to fulfill these aims”. (Project manager, Case A)

-

2.

The ‘professionalization’ pattern incorporates a partially different focus on the public financial management itself, assessing the opportunities of accounting change to enhance professionalism in financial and managerial accounting. Accrual-based accounting is valued as a trigger for capability development, and thereby a way to increase the effectiveness of accounting practices currently in place. The ‘hub’ of professionalization incorporates changing the formal structure of financial decision-making, in particular by more centralized accounting procedures. One of the Chief Financial Officers (CFO) (Case B) expressed this aim:

“We already provide a set of well-developed instruments of financial management (e.g., cost accounting, budgeting, accrued liabilities). What we are expecting is that the instruments are finally widely used”. … “The issue of centralization of financial accounting, which currently takes place in the public service units, is really only to be answered with a ‘Yes’. The departments have to go back to simple standard operating routines of bookkeeping”.

-

3.

Additionally, analysis reveals the influence of upper echelons and that only getting little more than their ‘sponsorship’ decreases the level of accounting change because of failures associated with subsequent gaps in strategic orientation, political support, or resource investments. The study found that achievement of induced outcome states depended both on value commitment and the scope of resource investments. This effect was obvious in the two middle-sized municipalities, where the shift to accrual-based accounting was valued and sponsored by the upper level (Case D: the Mayor; Case E: the CFO), but decreased because of lacking resource investments (e.g., by changing data systems evolutionarily) and a coherent leadership role and implementation strategy (e.g., weak in managerial authority).

Identifying patterns of accounting change in this way emphasizes that a local government might be focused on a prospective stance as, for instance, exhibited by self-evident rationales of accrual-based accounting change (Lapsley et al. 2009; Pina et al. 2009). Still, successful ‘corporate’ change interventions are limited by the actual opportunities to initiate such activities, in particular when a transformational outcome state is valued. In keeping with research so far, the portfolio of resource investments and the ‘order of implementation’ were observed to have a strong catalytic effect as antecedents of HRD and public service change. Thus, the analysis reveals evidence to distinguish two effects:

-

The rigidities of coping with the scope of resource investments, especially with reference to accounting knowledge allocation within the workforce (Gilbert 2005; Leonard-Barton 1992). The effect is illustrated by the cases where technological resource investments emerge evolutionarily (Cases D, E and F), because common threats of resource dependency in terms of increasing costs and the variety in time frames shaped the heterogeneity and, thereby, the suitability of HR trainings in place.

-

The relevance of the leadership role and implementation strategy, as the ‘order of implementation’ creates the capacity to constitute and link HR-related processes to governmental capability developments within the accounting change process (Kang and Snell 2009; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). Yet, implementation failures consider once more that not all research sites literally replicate the proposed effect. Examples can be found in the cases of the ‘sponsorship’ pattern. Less external support by upper echelons induced the weakness of leadership; thereby decreasing the strength of implementation activities exhibited by an informal and less coordinated ‘muddling through’-behavior.

Implementation failure (Cases C, D and E) as well as comparison of ‘modernizing’ (Cases A and F) and ‘professionalism’ (Cases B and C) illustrate a notable variance in change interventions, especially regarding the dispersed HR stock of (primarily cash-based) accounting knowledge (see Table 5 in Appendix, last column). Archival documents show that state-level modernization proposals and also all the six local authorities emphasized ‘person–job fit’ and to draw up certain HR training programs. As one consequence, modular concepts for HR training were initiated and implemented, but not evenly successful in all of the cases. Case C, for example, demonstrates the possible effect of tight budgets, as the scheduled HRD plan (‘roll out’) triggered political discussion and rejection by the municipal council. Contrastingly, the analysis reveals that HR training and weak assessment of workforce development remained an uncertain issue in the ongoing course of action. In particular, upcoming threats for HR investments were associated with the gap between formal restructuring of financial workflows and/or responsibilities (e.g., a more centralized configuration, upgrading of positions and redeployment of accountants) and an appropriate workforce development in terms of either assimilation of the current cash-based knowledge base (Cases B and C), or a more prospective accumulation of an accrual-based knowledge stock (Case A).

Identifying a ‘resource gap’ in this way was accompanied by two HR-related issues. Primarily, developing an appropriate knowledge base at the public service level required an enhanced HR training program supported by internal knowledge transfers. Secondarily, the allocation of accounting knowledge needed to be changed to accomplish a more prospective workforce development. Due to these effects, HR-related activities started to ensure that designated HR investments were in line with strategic aims of accounting change. By reference to HRD and the strength of HR systems, the temporal sequencing analysis of this study illustrated that the shift from administrative requirements of a short-term HR training to more transformational-related HR interventions gradually emerged.

Concerning the contextual analysis and the effects of strategic behavior, the aforementioned results according to HRD might be considered as two distinct patterns of strategic HR behavior. Following typological approaches previously developed in public HRM literature (Ridder et al. 2012a; Mesch et al. 1995), the next steps of analysis distinguish these patterns as either an administrative or strategic architecture of HRD, in particular to further specify how and why the specific outcome states at the different HR variables occur.

5.2 HR strategy formation: how does HR development and resource leveraging occur in accounting change?

Referring to new budget laws in Germany, HRD is acknowledged as a crucial factor for successful accounting change and, as such, considerable emphasis is given to designing HR training programs. For instance, the ‘Kommunale Gemeinschaftsstelle’—an association of German municipalities for managerial reforms (Reichard 2003)—prescribed a concept for a common HR training plan (in 2003, 2004). The inter-organizational project group itself revealed and published (in 2002, 2003) HRD practices of some of the municipalities as ‘best practice’-concepts. Accordingly, the necessity to invest in HRD was commonplace in the ongoing debate on how to put accounting change into practice.

Perhaps one of the most striking features of this study is to identify what HRD policies and practices occur as well as their change over time. Data analysis used the above-mentioned patterns of ‘corporate’ accounting change as the ordering variable to further describe the evidence of non-equivalence; in particular, to distinguish the outcome state of HRD systems as the criterion variable for the supplementary analysis of HR strategy formation. Moreover, further definitions of first-order categories of HRD were oriented by a criteria-based methodology using a set of concepts and measures which derived from research on strategic and public HRM (see Table 6 in Appendix; Gratton et al. 1999; Truss 2008, 2009a). This kind of analysis is valued because it provides a useful method to evaluate the (strategic) HR systems according to comparative analysis across the cases and temporal sequences. In particular, the descriptive analysis used cluster of performance and transformational-related HR systems to capture the induced value that should come into practice in terms of proposed effects at either the individual or organizational level. Additionally, analyzing HRM capacity and HR gap stressed the relevance of HR strategy formation. Hence, the analysis applied a multi-dimensional concept to investigate the formation and strength of HR systems across each of the six cases and over time.

A first summary inspection (see Table 6 in Appendix—second column: gap analysis) illustrated that processes to identify the HR gap were initially shaped by the short-term link between HR training and accounting change issues (e.g., preliminary fixing of accounting procedures, introducing software applications), which partially emerged as a more transformational-related and, at issue, strategic behavior (scanning workforce/leadership development). Moreover, it was indicated that opportunities to enhance the competence-related HR processes—from HR training to a more strategic workforce and leadership development program—diminished attention and efforts to launch complementary HR processes, in particular with regard to HR matters of financial performance management (objective setting, rewards). However, all of the interviewees acknowledged HR trainings as a key prerequisite to be successful (a); but further evaluation illustrated heterogeneity in the rationales when challenges attracted the attention to more sophisticated HRD processes (b).

(a) Initiation period: short-term trainings and gaps to HR development

-

In all of the research sites, a considerable need to identify required HR training was claimed. Moreover, accounting change introduction increased the efforts to develop accounting knowledge essentially necessary for ‘running the system’ when (cash-based) accounting systems were replaced. Within the initiation period, HR tasks were fixed, and the more prospective cases (Cases A, B and C) appointed HR task forces to design short-term HR trainings, covering identification of target groups, designing training programs or modules and fixing the delivery, including decisions about the provider (internal/external). Even in the prospective cases, the procedures to design short-term trainings were partly insufficient because of requirements to serve specific target groups (departmental/line management, politicians) and, in particular, their changing role within the developmental period. With one exception (Case F), this effect was illustrated across the sites, as all of them introduced ‘experience-based’ implementation procedures: The ‘roll out’ started with so-called pilot offices, mainly to gain initial results referring to the strength of implementation activities. Subsequently, activities were dominated by operational and ad hoc interventions with regard to the actual state of affairs. In the ongoing course of action, weaknesses of HR training schedules increased according to the variety of public services (e.g., size, configuration of financial tasks and procedures; Cases A, B and C), resource rigidities (e.g., time delays due to lacking technological investments; Cases D and E) and the significance of internal stakeholders less involved so far. For example, more entrepreneurial public service managers (e.g., Libraries; Cases C and D, Area/Facility management, Town Cleaning; Cases B and E) stressed the necessity to be both qualified and more involved within the ongoing change activities. Delivery of HR training also induced dependencies. For example, the ‘sponsorship’ cases (Cases D and E) exhibited such boundaries when HR training modules were not yet available within well-established partnerships with regional colleges of further education.

(b) Developmental period: re-alignment of transformational-related HR processes

-

As a consequence, assessing workforce development by designing short-term HR training remained a rather uncertain issue. This state was observed during the developmental period when the necessity increased to both develop the accounting knowledge stock and to further formalize and legitimize implementation schedules. The analysis revealed a set of upcoming managerial activities assigned to gather HRD gaps and stress the alignment of HR-related processes simply to have the accrual-based accounting knowledge in place when and where it is necessary.

Four of the research sites, the more prospective ‘modernization’ and ‘professionalization’ cases, respectively, developed such long-term consequences out of their strategic stance, in particular with reference to competence-related HR systems (workforce and leadership development). Thus, one of the ‘modernization’ cases (Case F) was exceptional because of its size and more informal and collaborative change interventions. The modernization agenda encouraged a process of organizational development (e.g., formal restructuring of public services), but the accounting workforce itself was very small and highly centralized, and therefore almost identical with the project group. Subsequently, workforce development and individual promotion were a side benefit of a more experience-based learning model of accounting capability development.

Contrastingly, the study exhibited the aim to strengthen and align the HRD system, notably to provide staffing suitable to accounting capability development (organizational level outcome), and to launch incentives expected by public employees with regard to their investment in accrual-based knowledge (individual level outcome).

In particular, both the ‘modernization’ and ‘professionalization’ pattern illustrate the sub-sequential effect of enhancing the work force planning and fixing an HRD program, but with quite different approaches: the ‘professionalization’ cases (Cases B and C, failed) valued a more needs-driven HRD strategy by a range of modular HRD programs assigned to specific target groups, whereas in Case A, resource flexibility is emphasized by a more opportunity-driven HRD strategy, in particular directed to locate ‘Certified Public Accountants’ at each organizational unit within the public service sphere. According to ‘professionalization’, the needs-driven approach (Case B) is also illustrated by a ‘Junior Special Program’, which was launched as an (individual) career opportunity to build a cadre of highly specialized accountants to support implementation activities by an ‘internal consultancy’ concept. The distinct value of such a core group appeared not only in individual promotion (Cases A and B) and higher payments (Case A), but also in a growing risk of headhunting. Promotion as well as turnover risks required job analysis and evaluation, and partly upgrading the accounting positions. Correspondingly, aims to restructure accounting workflows mentioned the necessity to dispose consequences for the accounting workforce (e.g., more centralizing, upgrading of positions, and redeployment of employees). As illustrated by Case A, the opportunity-driven HR strategy was assessed regarding the prospective workforce capability. Resource flexibility was the distinct value as considered by two observations. First, in cooperation with a regional college for public management education, the HR task force designed a course of studies with a final degree as ‘Certified Public Accountant’. Second, certified accountants were assigned to be at each public service unit ensuring the availability of accounting knowledge. Moreover, further consequences for the accounting workforce were stated by a financial officer (Case A):

“We don’t support the idea of rotation anymore: I would work three years with the social welfare office, then three years with the youth welfare office, then three years with the financial department and then again three years with the land registry office. This practice which we have followed up till now […] will not be continued anymore. Related to the financial and accounting system, we have recognized that we need more continuity, and we need specialized knowledge. And if somebody has first decided to work in this area, then he should also do so for a couple of years”.

Note that the outlined HR strategy was critically audited for two reasons: by the audit office because of its deficient input–output equation (HR input: high quality, costly; HR output: less specified) and therefore vague organizational benefits, and by department heads because of the individual benefits of higher education and, again, more vague departmental benefits. Thus, the distinctiveness of the HRD system triggered causal ambiguities as illustrated by the non-consensual agreements on its organizational benefits.

Hence, across the cases, work force planning was enforced, in particular to align operational requirements with long-term subjects of HRD due to the modernization agenda in place. The (strategic) value of HRD systems was also questioned because of the financial efforts necessary to either deliver the HR program itself (Case C, as it failed by rejection) or to serve for salary increases and their long-term compensation effects (Case A: audit office).

Considering the link between accounting change and the HRD system architecture in both periods, the study illustrated that the mediating effect of HRD stemmed from activities enabling a ‘resource gap’-analysis, and that effects of organizational failures induced the switch to a more strategic alignment of HRD policies and practices. This reflects prior research pointing out the necessity of vertical integration (Gratton 1999; Way and Johnson 2005), but it also reveals that forces of strategic alignment change over time. The temporal bracketing strategy of the study indicates evolving patterns of HRD in coping with a transformational situation in terms of the strategic direction represented by a prospective and probably radical stance of organizational change activities (Clardy 2008).

The study also illustrated the temporal nature and sequencing of this type of strategic integration. Whereas interviewees (e.g., project management, HRM) approved the need to be more adaptive in their HRM activities, the evidence indicates the heterogeneity of factors influencing the rationale as to how prospective change interventions and workforce development are aligned. First of all, the failure to create an HR strategy was a managerial shortcoming within the initial implementation phase. Second, with increasing pressures on a highly distributed accounting knowledge stock, failures to change resource investments came into being, partly caused by political decisions, or by a more short-term orientated leadership behavior. Third, the evidence indicated that the linkage was strengthened when the modernization agenda was associated with increasing organizational commitment to HR investments caused by the budget law and enhanced by the strategic direction of resource investment patterns. Therefore, the shift to transformational-related HR processes was built gradually by an ongoing assessment of workforce capability development.

Considering the HR department and its (strategic) role in identifying the HR gap, the study also demonstrated that HR strategy formation referred to the more general level of managing accounting change interventions. At first glance, cross-case analysis illustrated that HR departments had already started to re-launch their role as ‘personnel administration’, in particular claiming their ‘new’ position as HR service provider (see Table 6 in Appendix, first column). For instance, professionalism was indicated by centralized sub-units responsible for core HR systems, e.g., staffing, dual education and vocational trainings, or implementation of common HR programs, and also claimed by the HR department heads with reference to their individual professional education. A ‘delegation’-effect was also obvious because accounting change was not assigned to be a strategic domain of the HR departments. All research sites put the department of finance, in particular the CFO, in charge of change interventions. Hence, the role of the HR department was pre-configured by the implementation strategy and, possibly, executed by an HR task force. Thus, the antecedent responsibility for HRD seemed to be mixed and messy as to its gradual evolvement, and strategizing on HR matters appeared as a more vague and ambiguous area of activity.

5.3 Mediating antecedents to consequences: patterns of HR strategy formation

The previous analysis has outlined that accrual-based accounting introduction in local governments incorporates ‘corporate’ change interventions and, thereby, a set of possible consequences for HRD systems, in particular concerning rigidities associated with the portfolio of required resource investments. The results provided further evidence that the outcome state of HRD system changes is linked with strategic HR activities, respectively, enacting the role of HR change agency in terms of either an individual or group assigned to be responsible for leading HR-related processes. Hence, the outcome state remained ambiguous because of a ‘performing–learning’ tension (Smith and Lewis 2011) associated with the ‘delegation’-effect: at first glance, the uncertainty of performing (strategic) HRM activities associated with the devolution of HR managerial responsibility to the public service level, and, subsequently, that enacting HR change agency rests on the learning efforts to adjust HR systems within the enabling setting of accounting change interventions. Thus, the final step of analysis aims to explore how the HRD system changes emerge.

In keeping with the previous results, the antecedent ‘corporate’ change interventions set up different (and probably contradictory) circumstances to introduce HR-related change activities. Analysis also needs to check for (strategic) HRM capacity and the additional factors related to HR strategy formation, specifically to deliberately reflect replication logic at this stage of analysis. Tables 7 and 8 in Appendix summarizes the evidence using a form of predictor-outcome matrix (Miles and Huberman 1994: 213 et seq.). This type of a more causal case-ordered analysis covers the analytical steps to identify configurations of variables that contribute to a criterion variable. First, it summarizes the pattern of HR-related processes in order to essentially describe the main outcome. The first column (named as HRD processes) covers the criterion variable in terms of changing the HR stock (administrative/strategic), assembled as the most accountable outcome state according to both the precedent cross-case analysis and the literature discussed so far. The next step (second column) repeats the (strategic) HRM capacity, as described in the previous sections (HRM role/degree of strategic integration), in order to distinguish the state of HRM activities, whereas the remaining columns cover institutions to change in terms of the managerial and organizational routines actually in place, in order to further support the search for comprehensive patterns. Then, considering replication logic and the circumstances at the research sites, Tables 7 and 8 in Appendix reveals, first, the evidence of administrative HRD as a possible configuration (Part 1: Cases D and E), followed by evidence from the rival pattern of strategic HRD (Part 2: Cases A and B). Thereby, the analysis accounted for two exceptional circumstances, as mentioned above: the failure of accounting change (Case C) and a strongly different situation observed in the smallest research site (Case F). Thus, the analysis was based on two sets of matched-pair cases.

Prior research has outlined the significance of functional professionalism, strategic integration, and mutual relationships to cope with HR requirements within transformational change (Truss 2008, 2009b; Teo and Rodwell 2007). This study demonstrates that extending HR professionalism over time strengthens the HRM capacity in a context of accounting change, but the findings also exhibited effects that contradict the evolution of a strategic HR role, including ad hoc interventions of decision-makers (e.g., the mayor in cases of individual promotion), decentralization of HR managerial responsibility to the public service level, and, most importantly, the delegation of the assignment of strategic HR roles. Regularly, the HR departments claimed their administrative and transformational role to be ‘change agents’ and the need to be involved. For instance, HR officers in each case described how they had been involved in individual decision-making (e.g., staffing) or organizational change issues (e.g., restructuring of sub-units). But responsibility to initiate or legitimate HRM involvement was assigned to the enabling setting of accounting change interventions. Subsequently, the findings illustrated the risk of routine rigidity when a less successful implementation strategy put the enactment of HR strategy and also the associated role of ‘HR change agency’ at risk (Truss 2009a; Pichault 2007).

First, comparing the cases of administrative HRD reveals evidence that getting a little more than ‘sponsorship’ by upper echelons increased the risks for accounting change and, subsequently, for a strategically aligned pattern of HRD systems (see Table 7 in Appendix, part 1). According to this, the dilemma between a less professionalized HR department and HR responsibility delegated to a ‘weak’ domain of strategic behavior jeopardized the value assigned to HRD for accounting change. The effect occurs mainly related to (formal) authorization: managerial responsibility and, accordingly, project leadership were administered by financial officers as an additional task of their daily-workload, including specific risks of failure at the individual level (e.g., weak HR and change management skills or routines). Involving HRM capacity decreased with regard to the following three issues:

-

Referring to accounting change interventions, the level of experience with this type of a more complex and transformational change was low. Change circumstances similar to accounting change were not directed before. Indeed, the relevance of HR interventions (e.g., short-term HR training) was generally accepted, but project management as well as HR managers valued the actual necessity as low.

-

Within the HR departments, experiences with changing HR systems justified expectations that queried the adoption of ‘strategic’ HR change agency. This state is shown by Case D. Within the initiation period, the HR department arranged a task force to re-launch an outdated HR training procedure, but in its final phase, the proposed HRD system was rejected by the municipal council due to financial requirements. Similarly, in Case E, HRD systems change was a ‘planned project’ starting in 2001 and launched in 2005. Again, neither the HR department nor the HRD change activities were involved or aligned to accounting change interventions. As opposed to the designated HR role, HR officers delegated the responsibility for HRD-related processes to project management.

-

Managerial routinization in HRM or change activities is still ‘under construction’. Staffing of HR managers is based on administrative careers and further education in HRM issues. Also, HR managers lack professionalism as change agents due to short reform histories, limiting their opportunities to develop the required expertise.

In general, the HR departments initiated or continued functional professionalization, but strategic integration was confined to formal authorization. Managerial responsibility was partially vague, and HR-related initiatives were more or less explicitly delegated ‘upwards’, in particular because of the leading role of the accounting domain. The effect was twofold. First, initiation of HR investments depended on the HR expertise of project managers, and how HR interventions came to their interest. The state is illustrated in Case D. Gap analysis was limited to informal and ad hoc relationships in terms of project employees searching for HR-related expertise to deal with their latest implementation subjects. Second, the direction and sustainability of HR investments depended on the success and continuity of managerial leadership within the periods of change. When objectives or aims of resource investments changed (Case E), or when project management failed by turnover or promotion (Case D), then HR investments were put at risk. For example, in Case D, turnover of the CFO led to individual promotion of the project manager and his co-manager. As a result, managerial responsibility was weakened, and expertise in accounting and change management decreased. According to a similar situation, Case E exhibited the possibility to adjust and strengthen the HRM role. The status quo changed considerably as the CFO enforced redirecting accounting change to a more transformational approach. In this instance, the ‘HR department’ was substituted by an accounting consultancy and its responsibility for delivering the required HR training program.

Second, comparing the cases of strategic HRD in a context of more prospective accounting change interventions showed that a more dedicated implementation strategy regulated HRM activities in terms of assigning HRM responsibilities and the appointment of leadership roles (see Table 8 in Appendix, part 2). In both research sites, the ‘order of implementation’ creates managerial responsibilities for HR investments by drawing on formal authorization as well as repeatable patterns of change agency in terms of prior managerial experiences or organizational routines supportive enough to cope with the challenges of change activities. The data showed evidence that accounting change interventions are formally authorized as a core task of the financial department (Cases A and B). For instance, in Case B, the leadership role was assigned to a well-experienced financial officer and executed by a staff unit which strongly supports the implementation by a detailed scheduling of tasks. The HR department defined itself as a service provider for accounting change, and the chief HR officer demanded their involvement in the project management group. Subsequently, an HRD task force developed, administered and reviewed a modularized HR training program, and, thereby, prolonged it to a more sophisticated HR strategy in terms of developing a ‘professionalized accounting workforce’. Archival documents also illustrated comprehensiveness as well as political support, with reference to an internal, target-group oriented assessment of the necessity to develop the accounting workforce. Flexibility within this order stemmed from core elements: first, designing modularity within the HR training program, and second, realigning HR programs by the HRD task force when requirements changed. Additionally, a supplementary career program was provided to support and maintain internal knowledge transfers to organizational units and public services. The project leader explained the sources of HR change agency:

“We said: It is not sufficient that the offices are trained. We need people who accompany them consecutively. Those, who are there, are aimed to work 100 % exclusively for the envisaged task of ‘consulting’ the public service units. This has been an assessment of us, with no particular background”.

Contrastingly, the data reveal possible consequences of an institutionalized set of organizational rules and routines established to coordinate and exploit change activities due to a more or less successful history of modernization activities (e.g., mission statement, budget plans/controlling, internal benchmarking). Case A shows such an effect of embeddedness as the ‘order of implementation’ was caused by formally authorized rules and procedures (e.g., staff agreement) already directed to consolidate the enduring modernization process (initial date 1993). This was exhibited by well-established and accepted organizational routines which regulate the (formal) integration of organizational units (HR, technology) as well as the involvement of employees (staff council). Notwithstanding, accounting change interventions were similarly defined as a domain of the financial department with managerial responsibility assigned to the project group. However, as a project assistant stated: “The team falls back on well-established structures”. A final observation is important. Similar to the ‘internal consultancy’ approach (Case B), the relevance of sharing accounting knowledge emerged throughout the developmental period. Powered by first experiences at department level, a more formalized and integrated advisory and mentoring concept was arranged “symbolizing its fortune by a four-leaf clover” (project assistant, Case A). Thereby, the term integrated referred to the different fields of accounting expertise (financial, accrual, cost, and asset accounting) necessary to support the departmental transition to accrual-based accounting systems.

Referring to the concept of collective leadership in public service organizations, Denis et al. (2001) proposed a see-saw theory of strategic change and the impact of distributed leadership roles implying the need to cope with dilemmas concerned with these potentially opposing forces. When considering the link between accounting change interventions and the distribution of HR leadership roles, the temporal bracketing strategy of this study emphasizes distinguishing between two mechanisms when considering dynamic tensions within a process of HR strategy formation:

-

The delegation-effect because it stresses the ‘strategic’ HRM role in terms of the tension between professionalizing operational HR capabilities and the devolution of HRM responsibility to public services, to be balanced by formal authorization and, probably, an institutionalized set of organizational rules and routines;

-

The alignment-effect because it considers the ‘change agent’ HRM role in terms of the tension between short- and long-term effects of HRD, to be balanced by (emerging) managerial and organizational routines regulating the managerial responsibility for HR investments over time.

Overall, comparative analysis of the embedded patterns of HR strategy formation revealed that professionalism and operational involvement do not replace mechanisms to become more strategic in HRM in a context of accounting change interventions. This reflects previous findings (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Truss and Gill 2009), and illustrated that it is beneficial to further account for the evolution of HR change agency in public service organizations.

6 Discussion

Looking across the data analysis, the significance and variety of activities involved throughout the process underlying the emergence and outcome state of HR system changes in a context of organizational renewal in local governments is quite revealing. The term strategic HRM practices is useful as a label to distinguish HR activities and processes that are occurring when a HR strategy emerges and is performed (internal vertical fit) from those activities that are going on when HR systems are delivered, in terms of horizontal fit and the strength of operational HR practices in a specific area (e.g., staffing, compensation, or development). Rather than revealing homogenous efforts, the analysis has emphasized that strategic HRM practices involved varied throughout a process of HR strategy formation.

To further theorize on this distinction, the discussion reconsiders the initial frame and provides an extended graphic model (see Fig. 2) that aims to identify strategic HRM activities at three sequential stages in order to explain how the patterns of HRD system changes occur, thereby offering further understanding of the mechanisms navigating the comprehensive process.

Arrows (a1, a2, a3) in Fig. 2 display the distinct but even direct effects of (internal as well as external) institutional pressures on public service organizations that drive shifts in strategic behavior in organizational domains over time, for example in modernizing fields like accounting or HRM (a1). Moreover, latent tensions between institutional change dynamics according to such domains are linked together when institutional factors force deliberate organizational responses that inevitably involve cross-functional integration (a2), as that juncture revealing organizational tensions is more obvious and salient. Thus, a case of a comprehensive modernization agenda shaping the HRD system architecture so far (a3) encompasses a dialectic relationship as domain-specific change dynamics need to be seen as interrelated and probably contradictory forces that emerge and trigger HR-related change activities (Smith and Lewis 2011). Accordingly, previous studies on public HRM have pointed to the relevance of dual HR strategies (Kepes and Delery 2007), notably because public service organizations have to adjust their functional professionalism over time to remain effective when institutional forces change (Teo and Rodwell 2007; Truss 2008). Recognizing this type of a strategic tension indicates the significance of organizational rigidity and inertia when the effects of a more reactive or administrative HRM capacity are juxtaposed within the range of public service change processes (Alfes et al. 2010; Teo and Rodwell 2007; Liguori and Steccolini 2012). This emphasis on antecedents and the inherent tension of strategic HR behavior at organizational level of analysis needs to be complemented by a process-level analysis, in particular to untangle the sequencing of strategic HRM practices under which an outcome state of HR systems change is likely to occur.