Abstract

Background

The CHOICE care management intervention did not improve drinking relative to usual care (UC) for patients with frequent heavy drinking at high risk of alcohol use disorders. Patients with alcohol dependence were hypothesized to benefit most. We conducted preplanned secondary analyses to test whether the CHOICE intervention improved drinking relative to UC among patients with and without baseline DSM-IV alcohol dependence.

Methods

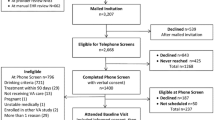

A total of 304 patients reporting frequent heavy drinking from 3 VA primary care clinics were randomized (stratified by DSM-IV alcohol dependence, sex, and site) to UC or the patient-centered, nurse-delivered, 12-month CHOICE care management intervention. Primary outcomes included percent heavy drinking days (%HDD) using 28-day timeline follow-back and a “good drinking outcome” (GDO)—abstaining or drinking below recommended limits and no alcohol-related symptoms on the Short Inventory of Problems at 12 months. Generalized estimating equation binomial regression models (clustered on provider) with interaction terms between dependence and intervention group were fit.

Results

At baseline, 59% of intervention and UC patients had DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Mean drinking outcomes improved for all subgroups. For participants with dependence, 12-month outcomes did not differ for intervention versus UC patients (%HDD 37% versus 38%, p = 0.76 and GDO 16% versus 16%, p = 0.77). For participants without dependence, %HDD did not differ between intervention (41%) and UC (31%) patients (p = 0.12), but the proportion with GDO was significantly higher among UC participants (26% versus 13%, p = 0.046). Neither outcome was significantly modified by dependence (interaction p values 0.19 for %HDD and 0.10 for GDO).

Conclusions

Among participants with frequent heavy drinking, care management had no benefit relative to UC for patients with dependence, but UC may have had benefits for those without dependence.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01400581.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are common and under-treated.1, 2 Because the vast majority of patients with AUD are not interested in or experience barriers to receiving specialty addiction treatment,2 experts have called for new treatment models and expansion of services across treatment settings, particularly in primary care.3,4,5,6

In response to these calls, several promising primary care–based models of care management for AUD have been developed and tested in randomized controlled trials with mixed results.7,8,9,10 One such care model was the nurse-delivered Considering Healthier drinking Options in Collaborative carE (CHOICE) intervention, designed to improve outcomes for patients at high risk of AUD.10, 11 CHOICE offered patient-centered chronic care management using motivational interviewing, repeated brief counseling, and shared decision-making over 12 months.10, 11 These intervention components11 were developed based on care previously shown to be effective specifically for patients with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) alcohol dependence.12

CHOICE was tested in a sample of patients at high risk for AUD, and patients were recruited to and engaged in the intervention regardless of the severity of their unhealthy alcohol use.11 The CHOICE model improved engagement with alcohol-related care, including 4-fold increases in medication use for alcohol dependence, but did not improve primary drinking outcomes or related symptoms.10 Because CHOICE was designed based on care shown to be effective among persons with alcohol dependence, we hypothesized a priori that patients with alcohol dependence would benefit most and stratified randomization of trial participants based on DSM-IV alcohol dependence. The present preplanned secondary analysis tested whether the CHOICE care management intervention improved drinking relative to usual care for patients with or without alcohol dependence at baseline.

METHODS

Study Description

The randomized controlled CHOICE trial compared usual primary care with usual care plus an offer of nurse care management (NCM CHOICE intervention) for primary care patients at high risk of AUD. Participants provided informed consent and then were randomized (1:1) to receive usual care or usual care plus the NCM CHOICE intervention. Randomization was stratified on the presence of alcohol dependence at baseline (defined based on DSM-IV criteria12, equivalent to moderate-severe AUD based on DSM-5), as well as sex and primary care site (n = 3) in permuted blocks of 6, 8, and 10, using computer-generated random numbers.11 Treatment assignments were concealed and provided by a study coordinator after completion of assessments during the baseline enrollment visit. The CHOICE trial and the present secondary analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System and Kaiser Permanente Washington.

Participants

The full CHOICE trial recruitment protocol has been detailed11 and summarized10 previously. The sample included 304 adult subjects, 275 (90%) of whom were male, from 3 primary care clinics associated with the VA Puget Sound Health Care System. The VA routinely screens the majority of primary care patients annually for unhealthy alcohol use13 using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire.14, 15 Patients were considered high risk for AUD and thus eligible for enrollment if they had documented AUDIT-C scores ≥ 4 (women) or ≥ 5 (men), received care at a participating primary care clinic, were age 21–75 years, and reported frequent heavy drinking on a phone screen (≥ 4 or ≥ 5 drinks per day for women and men, respectively, two times per week or once per week if any prior alcohol-related treatment). Participants were excluded from the trial if they were a VA employee; if they had acute medical or psychiatric instability, a behavioral warning flag in the electronic health record (EHR), any documented alcohol-related treatment in the past 90 days, cognitive impairment, and current or planned pregnancy; or if they were receiving end of life care, enrolled in another VA trial, excluded by their primary care provider, or provided inadequate contact information for follow-up. Eligibility was confirmed, and informed consent was obtained at the in-person baseline visit.

Assessments

At the in-person baseline visit, participants completed self-administered surveys and interviewer-administered questions.16 Participants were then re-assessed 3 and 12 months after baseline over the phone by an independent survey team that was blinded to group assignment. Primary outcomes were measured at 12 months.10

Nurse Care Management CHOICE Intervention and Usual Care Control

As described previously,11 the nurse care management (NCM) CHOICE intervention was delivered by two registered nurses and a nurse practitioner, supervised weekly by an interdisciplinary team. The intervention included an initial “engagement” visit with the nurse, subsequent repeated brief motivational interventions, progress monitoring, and follow-up for 12 months. The frequency of visits with the nurse was based on patient preferences, but we recommended follow-up every 1–2 weeks for 2 months and monthly thereafter, and next appointments were scheduled at the end of each contact. The number of visits received by CHOICE intervention participants ranged from 0 to 31 (mean 7 (SD 5.0), median 5). Patients with dependence at baseline had 0–31 visits (mean 7.8 (SD 6.8), median 5.0); participants without dependence had 0–23 visits (mean 6.9 (SD 5.8), median 5.0) (p = 0.39 for test of mean difference across dependence status). The nurse practitioner was available to prescribe and manage medications for AUD. Consistent with care management approaches for chronic conditions, nurses employed motivational interviewing and shared decision-making to help patients consider their drinking goal (stop drinking, cut back, self-monitor, or no change) and engage patients in care aligned with their values and preferences. Care options included patient self-monitoring and/or repeated biomarkers (gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT), and mean scorpuscular volume (MCV)) with feedback, medication (e.g., naltrexone), withdrawal management, and/or referral to specialty treatment or self-help groups.

Usual care included usual primary care at the VA, which includes annual behavioral health screening for unhealthy alcohol use, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); integrated primary care/mental health services; and referral to specialty mental health and addiction clinics as needed or desired.

Outcomes and Measures

Alcohol dependence was measured dichotomously (yes/no) based on DSM-IV criteria from the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) administered at baseline.17

Primary Outcomes

The primary outcomes were a measure of percent heavy drinking days (%HDD) and a dichotomous measure of a “good drinking outcome” (GDO) at 12-month follow-up. Both measures relied on the 28-day timeline follow-back interview (TLFB), a calendar-based, retrospective diary of alcohol consumption in the past 28 days.18, 19 Outcomes were selected to be relevant irrespective of patients’ goals. Heavy drinking was defined as ≥ 4 or ≥ 5 drinks per day for women and men, respectively, and assessed per potential (nonhospitalized) drinking day, and %HDD was the proportion of heavy drinking days among potential drinking days (maximum 28 days). “GDO” was defined as abstaining or drinking below NIAAA-recommended limits (no heavy drinking and ≤ 7 (women) or ≤ 14 (men) drinks per week) in the past 28 days and reporting no alcohol-related symptoms in the past 3 months on the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP)—a validated measure of the occurrence and frequency of alcohol-related consequences in which higher scores indicate greater consequences.20

Secondary Outcomes

%HDD and GDO were also measured at 3 months as secondary outcomes. Other secondary outcomes, measured at 12 months, all defined a priori, included secondary drinking outcomes, self-rated health, healthcare utilization, and process measures of alcohol-related care. Drinking outcomes included four measures derived from the 28-day TLFB (heavy drinking, percent days abstinent, abstinence, drinking below weekly limits); SIP score,20 and three readiness rulers (reflecting readiness to, importance of, and confidence in ability to change)21, 22. We measured self-rated health with a validated single-item health-related quality of life measure (SF-1),23 and healthcare utilization based on hospitalizations (any versus none), days hospitalized, and number of mental health and integrated primary care mental health visits. Process measures of care included four measures of care engagement (all accessible to intervention and usual care patients)—any receipt of FDA approved medications to treat AUD (naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram); any medication use greater than 30 days; engagement in VA specialty addictions treatment based on VA EHR data; and patient-reported involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. A composite measure was also created to assess engagement in any alcohol-related care.

Other Measures

Sociodemographic information included sex and age obtained from the EHR and race/ethnicity, marital status, education, and income reported at the in-person baseline enrollment visit. Additional measures, also obtained in person at enrollment, included mental health screening tests for depression,24 general anxiety disorder,25 trauma, and PTSD26; questions regarding help-seeking or receipt of alcohol treatment ever and in the year prior to enrollment; and the MINI for DSM-IV panic disorder, and non-tobacco drug use disorders (DUDs).17

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics were described in the total sample, as well as in those with and without alcohol dependence at baseline regardless of randomization assignment, and among those with and without alcohol dependence further stratified by randomization assignment.

For each group (those with and without alcohol dependence further stratified by randomization assignment), summary statistics (e.g., means, rates, or proportions) of primary and secondary outcomes were estimated using unadjusted generalized estimating equations (GEE) regression models with appropriate link function (e.g., logit for binary); robust (sandwich) variance estimators were used to account for dependency of outcomes from patients with the same primary care provider, and 95% Wald confidence intervals were constructed.

To assess the effect of the intervention on %HDD and GDO outcomes for participants with and without alcohol dependence at baseline, GEE binomial regression models with logit link were fit for %HDD (modeled as the probability of each nonhospitalized day in the past 28 days being a HDD due to bimodal distribution of HDD10) and for the binary GDO. As above, robust (sandwich) variance estimators were used to account for dependency of outcomes from patients with the same primary care provider. Two-sided Wald tests comparing outcomes across groups were conducted by testing the relevant contrast from GEE models that included main effects for baseline dependence and randomization intervention group and their interaction, and adjusted for sex, site, age, and baseline %HDD. Effect modification was evaluated for primary outcomes by testing whether the interaction term differed from zero.

Secondary outcomes were modeled similarly, though linear regression was used for continuous outcomes (e.g., readiness to change), Poisson models (with log link) were used for count data (e.g., utilization measures), and proportional odds models (with logit link) were used to assess overall health (SF-1). Additionally, unless otherwise specified, models adjusted for the corresponding baseline measure of the outcome.

Missing outcome data (~ 15%; see supplemental tables in Bradley et al.10) were addressed using multiple imputation with chained equations using 30 imputations. This approach assumes data are missing at random. Sensitivity analyses were conducted, repeating all primary analyses among complete cases. All tests were 2-sided and significant at alpha level of 0.05, and all analyses were conducted using R statistical software.

RESULTS

Among 304 patients consented and randomized, 150 were randomized to the intervention. Fifty-nine percent (in both intervention and usual care) met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol dependence at baseline. In the overall sample, participants with dependence were younger on average than those without dependence, as well as more likely to report current smoking; to screen positive for depression, suicidality, anxiety, and PTSD; and to meet criteria for panic and drug use disorders, and more likely to report treatment, self-help, or general help-seeking for their alcohol use ever and in the year prior to enrollment (Table 1). Similar trends were observed across dependence status within the intervention and usual care groups (Table 1).

Results of primary outcomes at 12 months are presented in Table 2 stratified by baseline alcohol dependence status. For participants with baseline alcohol dependence, no significant differences were observed at 12 months in mean %HDD or the percentage of patients with a GDO (%HDD 37% intervention versus 38% usual care, p = 0.76 and GDO 16% intervention versus 16% usual care, p = 0.77). For participants without dependence, %HDD did not differ (intervention (41%) versus usual care (31%) (p = 0.12)), but the proportion with a GDO was significantly higher among usual care participants (26% versus 13%, p = 0.046), at 12 months. In both cases, the interaction term was not statistically different from the null (p values = 0.19 for %HDD and 0.10 for GDO). Findings for %HDD and GDO at 3 months (also presented in Table 2) were similar to those at 12 months for patients with and without alcohol dependence at baseline.

Additional secondary outcomes are presented in Table 3 for patients with and without baseline alcohol dependence. For those with dependence at baseline, most secondary drinking outcomes did not differ across intervention status at 12 months, though the percent of patients with no heavy drinking days was higher in the intervention than the usual care group, mean self-reported health status (SF-1) trended toward higher values among participants in the intervention relative to those in usual care (p = 0.05), and the number of mental health visits was lower for intervention than usual care participants (Table 3). In contrast, for those without dependence at baseline, the percent days abstinent, the proportion of participants reporting abstinence from alcohol use, and the proportion reporting drinking below recommended weekly limits at 12 months were all significantly higher among participants randomized to the usual care group than those randomized to receive the intervention (Table 3).

The intervention was associated with increased alcohol-related care for participants both with and without alcohol dependence at baseline (Table 4). For both groups, a greater proportion of participants randomized to receive the intervention than those receiving usual care filled any prescription and had medication use > 30 days over 12 months of follow-up. And, for participants with dependence at baseline but not those without, the intervention was associated with greater receipt of any alcohol-related care over 12 months of follow-up (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Alcohol dependence was common among patients at high risk for AUD who consented to participate in a trial of the CHOICE care management intervention. Contrary to a priori hypotheses, no significant effect modification of the intervention by dependence status was observed for primary outcomes, and patients with dependence did not appear to benefit from the CHOICE intervention more than those without dependence. In fact, patients without dependence were more likely to have a good drinking outcome—drinking below recommended limits without symptoms—if they were randomized to usual care compared with those offered the intervention. Findings that the intervention did not benefit those with dependence were surprising given that participants randomized to the intervention had greater receipt of alcohol-related care compared with those receiving usual care—specifically a 3-fold increase in AUD medication use. This additional receipt of care among intervention patients was expected to improve drinking outcomes in this subgroup, but it did not. Because CHOICE explicitly recruited patients for a study focused on their drinking, and because about one-third of participants without dependence and two-thirds of those with dependence reported prior treatment and/or self-help participation, patients who were ultimately recruited to the study may be a biased sample of patients. Specifically, these patients might have had more severe alcohol use and potentially more treatment-resistant AUDs than general primary care patients with frequent heavy drinking. Further, the majority of enrolled patients with dependence had mental health and/or substance use comorbidity, which are associated with poorer response to treatment; prior trials in which alcohol care management was effective in VA patients excluded patients with other drug use disorders.8, 27 In the main CHOICE trial, and among participants with dependence at baseline in the present study, the intervention was associated with reduced mental health utilization, potentially due to a substitution effect whereby patients might have perceived NCM visits as counseling and might therefore have foregone more specialized mental health services. Untreated or insufficiently treated psychiatric comorbidities may contribute to the negative findings among patients with dependence. Further research is needed to identify optimal primary care–based models for helping patients with alcohol dependence reduce their drinking; it is possible these patients need more intensive treatments and/or treatment models that more comprehensively address psychiatric and substance use comorbidity.

That patients without alcohol dependence reported better drinking outcomes if they were randomized to usual care, compared with those randomized to the intervention, was also unexpected. Among participants without alcohol dependence, greater improvement in secondary drinking outcomes (largely reflecting abstinence) among usual care than intervention participants helps clarify these findings and may have important implications for researchers and clinicians. Specifically, we consistently identified improved drinking outcomes—including one primary outcome and 3 secondary outcomes at 12 months (2 reflecting abstinence)—in non-dependent patients who were not offered the CHOICE intervention. These findings should be interpreted with caution—the CHOICE study was not powered on secondary outcomes or subgroup analyses, no statistically significant interaction was identified between intervention assignment and baseline dependence, and results may be spurious given multiple comparisons. It is also possible that these findings reflect differences in social desirability bias in participants without dependence assigned to usual care relative to those assigned to the intervention. Indeed, while measures of alcohol use decreased, neither patient-reported problems nor readiness to change differed across intervention status at 12 months among those without dependence at baseline. However, the consistency of results across drinking outcomes suggests the possibility that this unexpected finding may reflect true changes in drinking and that, at a minimum, it may be important to consider how the CHOICE intervention might have worsened outcomes compared with usual care.

It is possible that the recruitment, enrollment, and assessment protocols, combined with societal and medical norms that patients who develop problems due to drinking must abstain, together contributed to increased abstinence and good drinking outcomes in non-dependent patients randomized to usual care. Anecdotal reports from patients at their initial visit with the CHOICE nurses indicated that the letter from provider or the baseline assessment made them realize they needed to make changes. Further, one patient who was approached for telephone screening but declined called our study voice mail about 3 months later and reported that the call upset him but had prompted him to stop drinking and smoking and that he felt great. Participants randomized to the intervention also told CHOICE nurses that they were surprised they were allowed to choose their drinking goals (e.g., to cut down versus abstain). This suggests that patients assigned to usual care who were activated by recruitment protocols might have assumed they needed to stop drinking. Alternatively, they might have encountered primary care or mental health clinicians who advised them to abstain. Further, those that did not meet criteria for dependence might have been more able to abstain without formal treatment than those who did.28, 29 These findings, along with another ineffective care management intervention that did not offer advice to abstain,9 and two effective care management interventions that appeared to include explicit advice to abstain,7, 8 suggest to us that clear medical advice to abstain might be a critical ingredient in effective patient-centered care primary care interventions targeting patients at high risk for AUD. This should be tested in future interventions among primary care patients at high risk for AUD with and without alcohol dependence.

Findings should be viewed in light of several limitations. First, drinking outcomes improved over time in all subgroups, which may reflect regression to the mean, social desirability bias, and/or assessment effects. Similarly, recall bias in self-report data could be present and could differ based on group assignment if the intervention, in which the nurse encouraged self-monitoring and taught participants about standard drink sizes, led to more accurate reporting. Second, although this evaluation was planned a priori and assessed a priori targeted primary outcomes, this study reflects a secondary analysis of intervention effects across subgroups and was likely adequately powered to detect only large effect modification. Third, we conducted multiple comparisons, which may have resulted in spurious findings; of the 32 outcomes assessed at 12 months (18 among dependent and 18 among non-dependent participants), approximately 1 in each group would be expected to be significant at the 0.05 level due to chance. Finally, several generalizability limitations should be noted. Because only 53% of approached patients enrolled and consented to participate in a trial focused on alcohol use, results may not be generalizable to primary care patients at high risk for AUD, generally. Results may also not generalize to women (Veteran or non-Veteran), non-Veterans, and/or Veterans receiving primary care outside of the VA.

Despite these limitations, this study provides suggestive information regarding care models that could be tested for patients with frequent heavy drinking who do and do not have alcohol dependence. Though the intervention was specifically designed to incorporate treatments previously shown to be effective for patients with alcohol dependence,11 we found no evidence that the effect of the intervention differed across dependence status. Further, we found suggestive evidence that, for patients without dependence, the intervention may have reduced the likelihood of a good drinking outcome 12 months later. For those participants without dependence, recruitment, enrollment, and assessment protocols may have catalyzed greater change among usual care than intervention participants. Future studies should test whether explicit medical advice to abstain influences drinking outcomes among patients with high-risk drinking, with and without moderate to severe DSM-5 alcohol use disorders. Other elements of the recruitment and assessment procedures used in this study may also help catalyze change and could be tested in future trials.

References

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams JL, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;348(26):2635–2645.

Cohen E, Feinn R, Arias A, Kranzler HR. Alcohol treatment utilization: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;86(2–3):214–221.

Bradley KA, Kivlahan DR. Bringing patient-centered care to patients with alcohol use disorders. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1861–1862.

Institute of Medicine. Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems: A Report of the Committee for the Study of Treatment and Rehabilitation for Alcoholism. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1990.

Saitz R. Alcohol dependence: chronic care for a chronic disease J Bras Psiquiatr 2005;54(4):268–269.

McLellan AT. Reducing heavy drinking: a public health strategy and a treatment goal? J Subst Abus Treat 2007;33(1):81–83.

Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative Care for Opioid and Alcohol Use Disorders in Primary Care: The SUMMIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(10):1480–1488.

Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto SA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:162–168.

Saitz R, Cheng DM, Winter M, et al. Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(11):1156–1167.

Bradley KA, Bobb JF, Ludman EJ, et al. Alcohol-Related Nurse Care Management in Primary Care: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178(6).

Bradley KA, Ludman EJ, Chavez LJ, et al. Patient-centered primary care for adults at high risk for AUDs: the Choosing Healthier Drinking Options In primary CarE (CHOICE) trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2017;12(1):15.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (Text Revised). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Bradley KA, Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Volpp B, Collins BJ, Kivlahan DR. Implementation of evidence-based alcohol screening in the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care 2006;12(10):597–606.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(16):1789–1795.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(7):1208–1217.

Aertgeerts B, Buntinx F, Ansoms S, Fevery J. Screening properties of questionnaires and laboratory tests for the detection of alcohol abuse or dependence in a general practice population. Br J Gen Pract 2001;51(464):206–217.

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59 Suppl 20:22–33;quiz 34–57.

Sobell LC, Brown J, Leo GI, Sobell MB. The reliability of the Alcohol Timeline Followback when administered by telephone and by computer. Drug Alcohol Depend 1996;42(1):49–54.

Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a Timeline Method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addict 1988;83:393–402.

Kiluk BD, Dreifuss JA, Weiss RD, Morgenstern J, Carroll KM. The Short Inventory of Problems - revised (SIP-R): psychometric properties within a large, diverse sample of substance use disorder treatment seekers. Psychol Addict Behav 2013;27(1):307–314.

Williams EC, Horton NJ, Samet JH, Saitz R. Do brief measures of readiness to change predict alcohol consumption and consequences in primary care patients with unhealthy alcohol use? Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(3):428–435.

Bertholet N, Gaume J, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Daeppen JB. Predictive value of readiness, importance, and confidence in ability to change drinking and smoking. BMC Public Health 2012;12:708.

Desalvo KB, Jones TM, Peabody J, et al. Health Care Expenditure Prediction With a Single Item, Self-Rated Health Measure. Med Care 2009.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–613.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

Blanchard E, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley T, Forneris C. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther 1996;34(8):669–673.

Willenbring ML, Olson DH. A randomized trial of integrated outpatient treatment for medically ill alcoholic men. Arch Intern Med 1999;159(16):1946–1952.

Sobell LC, Cunningham JA, Sobell MB. Recovery from alcohol problems with and without treatment: Prevalence in two population surveys. Am J Public Health 1996;86(7):966–972.

Sobell LC, Ellingstad TP, Sobell MB. Natural recovery from alcohol and drug problems: methodological review of the research with suggestions for future directions. Addiction. 2000;95(5):749–764.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who participated in the CHOICE trial, and their primary care providers, as well as VA clinical leaders in primary care, integrated mental health, mental health specialty clinics, psychiatric emergency services, laboratory services, pharmacy, and addictions treatment who supported completion of the CHOICE trial. We also thank others who supported this study administrative, clinically, or via service on the Data Safety Monitoring Board. Funding and support for this study came from the NIAAA (R01 AA018702 and K24 AA022128) and VA Health Services Research & Development Career Development Award (CDA 12-276). Additional in-kind support was provided by the Seattle CESATE and VA Puget Sound HSR&D, as well as Kaiser Permanente Washington Behavioral Health Service.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The CHOICE trial and the present secondary analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System and Kaiser Permanente Washington.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States Government, the University of Washington, or Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, E.C., Bobb, J.F., Lee, A.K. et al. Effect of a Care Management Intervention on 12-Month Drinking Outcomes Among Patients With and Without DSM-IV Alcohol Dependence at Baseline. J GEN INTERN MED (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05261-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05261-7