Abstract

Background

Implicit and explicit bias among providers can influence the quality of healthcare. Efforts to address sexual orientation bias in new physicians are hampered by a lack of knowledge of school factors that influence bias among students.

Objective

To determine whether medical school curriculum, role modeling, diversity climate, and contact with sexual minorities predict bias among graduating students against gay and lesbian people.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Participants

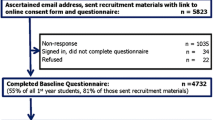

A sample of 4732 first-year medical students was recruited from a stratified random sample of 49 US medical schools in the fall of 2010 (81% response; 55% of eligible), of which 94.5% (4473) identified as heterosexual. Seventy-eight percent of baseline respondents (3492) completed a follow-up survey in their final semester (spring 2014).

Main Measures

Medical school predictors included formal curriculum, role modeling, diversity climate, and contact with sexual minorities. Outcomes were year 4 implicit and explicit bias against gay men and lesbian women, adjusted for bias at year 1.

Key Results

In multivariate models, lower explicit bias against gay men and lesbian women was associated with more favorable contact with LGBT faculty, residents, students, and patients, and perceived skill and preparedness for providing care to LGBT patients. Greater explicit bias against lesbian women was associated with discrimination reported by sexual minority students (b = 1.43 [0.16, 2.71]; p = 0.03). Lower implicit sexual orientation bias was associated with more frequent contact with LGBT faculty, residents, students, and patients (b = −0.04 [−0.07, −0.01); p = 0.008). Greater implicit bias was associated with more faculty role modeling of discriminatory behavior (b = 0.34 [0.11, 0.57); p = 0.004).

Conclusions

Medical schools may reduce bias against sexual minority patients by reducing negative role modeling, improving the diversity climate, and improving student preparedness to care for this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Improving the health and well-being of sexual minorities has been identified as a priority of the Healthy People 2020 initiative,1 the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,2 and the Institute of Medicine.3 One factor in the poorer health of sexual minorities relative to the general population4 is that they may receive lower-quality healthcare, in part because of provider bias.5 , 6 Provider sexual orientation bias includes explicit bias and implicit bias (unconscious preference for heterosexual people relative to gay men and lesbian women). Both impact verbal and nonverbal communication and decision making.7 – 11

Medical school may be an ideal window for interventions to reduce bias because of students’ rapid socialization into the field of medicine. Students are exposed to diverse patients as well as the opinions, attitudes, and behaviors of faculty who impart on students professional norms and expectations, reflecting their biases.12 Accordingly, medical schools are committed to educating students about the potential impact of bias.13 However, there is little focus on sexual minorities at risk for disparities and no consistent approach. Intervention strategies vary widely and include health equity14 or cultural competency workshops/lectures,13 service learning, or other programs to increase student contact with diverse communities.15

There is little data to guide educators. The majority of bias reduction programs have face validity but little rigorous testing.16 The Cognitive Habits and Growth Evaluation (CHANGE) Study was designed to provide insight to medical school leaders on factors that affect change in bias against stigmatized groups, and to help guide interventions. In this paper we examine the association between changes in heterosexual students’ implicit and explicit sexual orientation bias and four domains of medical school training: 1) formal curriculum and training relevant to patient-centered attitudes and skill at providing care to diverse groups; 2) role modeling, or exposure to faculty and residents’ negative attitudes and discriminatory behavior toward sexual minorities; 3) sexual orientation diversity climate, or the perception that the school is a safe space for sexual minorities; and 4) contact with sexual minorities and the perceived favorability of those encounters. This research was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

METHODS

Sample

The longitudinal CHANGE Study follows medical students who matriculated in US medical schools in the fall of 2010. We randomly selected 50 medical schools from strata of public/private schools and six regions of the country, using sample proportional to strata size methodology. One school had unique characteristics (military school) that would have limited the generalizability of study findings and was excluded, leaving a sample of 49 schools.17 In fall 2010, 5823 first-year medical students (MS1; 68% of MS1 in sampled schools) were invited via email to participate in a web-based survey. All students were in the first semester of medical school. Multiple methods were used to ascertain the email addresses of MS1 (see van Ryn et al. 201518). The sample of 4732 students consisted of 81% of those invited, and 55% of MS1 at study schools (see Fig. 1). All participants completed a survey of explicit biases toward several groups, including sexual minorities; 50% of the sample (n = 2362) were randomized to complete the sexual orientation implicit association test (IAT), a validated measure of implicit sexual orientation bias. In spring 2014, students completed a second survey during their final semester of medical school. Completed surveys were returned by 3959 students (81%). Those who indicated that they were not third- or fourth-year students (n = 203) were excluded, leaving a longitudinal sample of 3756 students; 1767 completed the IAT at both time points. Students who identified a sexual orientation other than heterosexual or straight at either year 1 or year 4 (n = 264) were excluded from analysis, leaving 3492 students, 1593 of whom completed the IAT at both time points. Students were asked at year 1 “What is your sexual orientation,” with responses of “heterosexual,” “bisexual,” “homosexual,” or “other.” At year 4, they were asked “Do you think of yourself as…,” with responses of “heterosexual or straight,” “gay or lesbian,” “bisexual,” “something else,” or “do not know.”

Outcome Measures

Implicit sexual orientation bias was measured at years 1 and 4 using the IAT.19 , 20 The test presents images representing same-gender or different-gender relationships that participants categorize with positive or negative words under time pressure. Difference scores were calculated that represent a continuum of strong anti-heterosexual to strong anti-sexual minority bias (−2 to 2). Respondents indicated explicit bias using two continuous feeling thermometers numbered from 0 (very cold or unfavorable) to 100 (very warm or favorable) in their feelings toward 1) “gay men” and 2) “lesbians.”21

Predictor Measures

Formal curriculum is one medium for improving students’ skill and comfort in providing care to diverse patients. We operationalized the formal curriculum using 12 measures (see Table 2). Students self-reported the hours of training related to cultural awareness, empathy, communication skills, and partnership-building skills. We also assessed their participation in training related to broadening their perspective on diverse communities. The effectiveness of education in caring for sexual minority patients was assessed through students’ perceived preparedness to care for sexual minority patients and perceived skill at counseling LGBT patients on safer sex practices.

Role modeling is an important medium for learning professionalism. It is one element of the informal or “hidden” curriculum that has been shown to influence student learning.12 , 22 Students were asked 1) how often in medical school they witnessed discriminatory treatment of an LGBT patient and 2) how often they heard professors or residents make negative or derogatory comments about LGBT patients. We calculated a mean of these two items representing student-level exposure to negative role modeling as well as a within-school average of these scores.

Sexual orientation diversity climate included 1) the percentage of students within the school who reported witnessing discriminatory treatment of LGBT patients and 2) the perception of a safe climate for LGBT students. Students reported whether they had witnessed specific micro-aggressions: receiving lower evaluations for unfair reasons, being treated in an unfriendly way, being subjected to offensive names/remarks, being treated with less respect than other students, being publicly humiliated, and being ignored by a resident or attending physician. For each type of micro-aggression, students rated on a five-point scale (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely) the likelihood that the behavior was due to the victim’s sexual orientation. We created a dichotomized variable where students who reported that events were at least “a little” likely to have been due to sexual orientation were coded as 1, and those who observed no such events or did not believe that these events were due to sexual orientation were coded as 0. We also included a previously created variable school-level measure of representing non-heterosexual students’ (excluded from main analyses) experiences of sexual orientation micro-aggression. We computed the mean of items, measuring the likelihood that micro-aggressions were due to sexual orientation, for each non-heterosexual student, and used these scores to calculate a school-level variable representing micro-aggression due to sexual orientation experienced by sexual minorities.

Contact with sexual minority populations

included students’ report, on a four-point scale, of the 1) amount and 2) favorability of their interaction with “LGBT medical students,” “LGBT faculty, attendings, or residents,” and “LGBT patients.” Responses were averaged to form one measure of amount of contact and one measure of favorability of contact.

Covariates

Common survey questions measured age, gender, race, and ethnicity at baseline. Respondents selected multiple race groups, which were categorized into a variable representing racial/ethnic identification as black, Hispanic, East Asian, South Asian, or white. Socioeconomic status was estimated by selecting a category representing the family’s income during high school. Categories were combined into income < $50,000, $50,000–74,999, $75,000–99,999, $100,000–249,999, or ≥ $250,000. Participant tendency to respond to survey items in a socially desirable way was measured at baseline using six items from the Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale.23

Analysis

We conducted hierarchical linear modeling to assess associations between each predictor and year 4 implicit or explicit bias, adjusted for year 1 bias. We report unstandardized beta coefficients representing change in the dependent variable per one unit change in the independent variable, and corresponding p-values. Models were adjusted for gender, age, race/ethnicity, and social desirability bias and included a random intercept for school. Predictors were first modeled individually (adjusted for covariates). To avoid eliminating variables early in the model-building process whose effects may be confounded by un-modeled variables, we retained variables associated at p < 0.2 to enter into domain-specific models (formal curriculum, role modeling, sexual orientation diversity climate, and contact with sexual minority people). Variables significant in domain-specific models at p < 0.2 were then entered into one multi-domain model for each outcome. Variance inflation factors and effect decomposition were evaluated to assess collinearity in domain-specific and final models.

RESULTS

Sample demographics are presented in Table 1, and distributions of outcomes and key predictors are presented in Table 2. Overall, students’ implicit bias against sexual minorities was reduced during medical school. Average implicit bias decreased at 42 schools and increased at seven schools. Using commonly reported cutpoints,24 this shift represents a change from moderate-strong bias to moderate bias (\( \overline{x} \)= 0.45 [SD = 0.46] to 0.34 [0.44]). Explicit bias also shifted toward more favorable opinions about gay men (76.97 [23.93] to 78.76 [22.80]) and lesbian women (76.69 [23.50] to 78.18 [22.45]). Average explicit bias against gay men was reduced in 34 schools, increased in 14, and remained the same (within 0.05 point) in one school; explicit bias against lesbian women was reduced in 32 schools, increased in 15, and remained the same in two.

Table 3 presents associations between each school factor and bias in models adjusted only for covariates. Table 4 presents domain-specific models, and Table 5 presents the results of the multi-domain multivariate models. In final models, lower year 4 explicit bias against gay men was associated with feeling prepared to provide care for a gay, lesbian, or bisexual patient (beta coefficient = −2.46, p < 0.001), feeling skilled at counseling LGBT patients on safer sex practices (b = −0.77, p = 0.02), and having more favorable interactions with LGBT faculty, residents, students, and patients during medical school (b = −8.05, p < 0.001). Higher year 4 bias against gay men was associated with participating in structured service learning (b = 1.46, p = 0.03) and perception of more faculty role modeling of discriminatory behavior.

Lower year 4 explicit bias against lesbian women was associated with feeling prepared to handle a sexual minority patient (b = −2.74, p < 0.001), skill at providing safe sex counseling to LGBT patients (b = −0.95, p = 0.005), and favorability of interactions with LGBT students, faculty, or patients (b = −7.92, p < 0.001). Higher year 4 bias against lesbian women was associated with greater likelihood that sexual minority students experienced discrimination that they attributed to their sexual orientation (b = 1.43, p = 0.03). A sensitivity analysis of the effect of including the school mean of role modeling in explicit bias models found that it did not affect the association between individual-level role-modeling exposure and bias change.

Reduced implicit bias was associated with more frequent interaction with LGBT students, faculty, and patients (b = −0.04, p = 0.008), and reporting more faculty role modeling of discriminatory behavior (b = −0.04, p = 0.02). However, independent of each student’s observations of negative role modeling, reduced implicit bias was associated with less faculty role modeling of discriminatory behavior reported by all students at the school (b = 0.34, p = 0.004).

DISCUSSION

To ensure a primary care workforce equipped to provide high-quality, equitable care to all communities, medical schools must work to eliminate biases that influence the judgment and behavior of new physicians. Medical school factors from each domain were associated with change in implicit and explicit sexual orientation bias. Within the formal curricula, hours of training in cultural competence or diversity issues was not associated with change. This is consistent with literature suggesting that this type of training, as it is commonly implemented, is ineffective.25 These activities may also focus more heavily on bias toward racial minorities, and thus are less likely to influence sexual orientation bias. Preparedness for handling a gay, lesbian, or bisexual patient and skill at counseling sexual minority patients on safer sex practices was associated with reduced explicit bias. Medical school may be the first time students discuss sexual orientation in a professional environment. Our results suggest that sexual orientation bias could be reduced through training to increase skill in caring for sexual minorities.

Participation in service learning is one way for students to interact with diverse patients and gain new perspectives on care for underserved communities.26 It has been shown to improve students’ attitudes about the communities they serve.15 Service communities are probably no less likely to include sexual minorities than others, and our measure did not specify the characteristics of the community in which the experience occurred. It is surprising that participation in these programs was associated with increased explicit bias toward gay men. Studies have shown that patient care experiences in medical school are associated with reduced empathy and idealism.27 Perhaps experiences of providing care in low-resource communities had a similar effect on empathy and other prosocial attitudes, including explicit bias. This would not account for the difference in effect between attitudes toward gay men and lesbian women. This association requires additional study.

Faculty role modeling influences medical students’ professional development.12 We found differences between witnessing negative role modeling and being in an environment where others noticed negative role modeling. Witnessing faculty use derogatory humor, make negative comments, or discriminate against sexual minority patients was associated with reduced implicit bias; however, the school mean for frequency of witnessing those behaviors was significantly associated with increased implicit bias. Thus, medical schools where unprofessional behavior is more common may be more likely to increase students’ implicit bias, but independent of that relationship, students who notice and recall these instances may be more likely to have lower implicit bias. This is a novel finding, and one that warrants further investigation, but it also suggests a possible two-stage intervention approach: increasing awareness and knowledge of what behaviors are discriminatory or unprofessional, and adopting policies that communicate that discriminatory behavior is not tolerated.

Among sexual orientation diversity climate variables, the only significant predictor of change was the school-level mean of non-heterosexual students’ reports of discrimination. Specifically, heterosexual students’ explicit bias against lesbian women increased in schools where sexual minority students reported experiencing more discrimination due to sexual orientation. This relationship was only marginally significant (p = 0.04), and no similar relationship was observed for explicit bias toward gay men, so these associations should be interpreted with caution. This finding suggests that the sexual orientation diversity climate of medical schools can influence bias toward sexual minority people. Furthermore, this finding points to the importance of assessing the experiences of sexual minority students, which can reveal information about the school climate that heterosexual students’ reports do not. There is a dearth of information in medical school curricula about LGBT health and very little cultural competency education that considers the experiences of these stigmatized minority groups.28

Contact has been shown to reduce bias and improve intergroup relations under certain conditions (equal status, shared goals). We found evidence that both the amount of contact with sexual minorities and the perceived quality of that contact were associated with reduced bias during medical school. The amount of contact predicted reduced implicit bias, and favorability was associated with reduced explicit bias against gay and lesbian people, reaffirming prior research showing that contact reduces negative attitudes about sexual minorities.29 , 30 It is also consistent with research suggesting that the impact of contact on implicit bias occurs unconsciously and automatically, whereas its impact on explicit bias is mediated through increased empathy and reduced intergroup anxiety,31 , 32 which may require more emotional investment and information sharing during the interaction. Interventions should consider increasing exposure by focusing on policies and practices that improve recruitment and retention of diverse students and faculty, and collecting sexual orientation information from patients to increase students’ awareness of diverse patients. Interventions should also consider interaction quality, which can be achieved by training students in partnership-building skills to improve the quality of patient encounters and by fostering an environment where sexual minority faculty and students feel they can disclose their sexual orientation.

This study has several limitations. First, data were collected between 2010 and 2014, so attitudes may have changed since that time. Second, many medical school experiences were self-reported at the same time bias was measured; therefore, bias in year 4 and responses to items measuring school factors may both be influenced by external variables. However, the longitudinal nature of the data improves the internal validity of the study, since year 1 bias was measured before the experiences that are reported in year 4. Associations of change in bias with school average measures strengthen the validity of findings, since these variables were computed externally rather than reported directly by each participant. Additionally, the IAT has been shown to be resistant to attempts to attain a socially desirable score.19 Many of our measurements, such as service learning or cultural competence training, did not explicitly ask about experiences or content related to sexual minority individuals. This lack of specificity may have influenced our findings. Additionally, measures of role modeling focused on negative experiences, without providing an opportunity to report positive role modeling, and micro-aggressions were dichotomized in such a way that any indication that they might have occurred due to sexual orientation was considered as being related to sexual orientation. Both of these decisions may lead to recording more negative experiences compared to other measurement strategies. Another limitation is the unknown sampling probability of students due to the nature of snowball recruitment.18 However, the response and retention rate for this study exceeds that of other studies of medical students. Schools were randomly selected from strata, improving sample representativeness. Finally, an analysis of the race, sex, and age of students in the sample compared to medical students nationally found similar distributions.

This study is the first to assess relationships between longitudinally measured implicit and explicit sexual orientation bias among medical students and school-level factors and experiences in a national sample of medical schools. Medical student biases toward sexual minorities may improve during medical school with training in providing care to sexual minorities, improved diversity climate, less negative role modeling, and more favorable interaction with sexual minorities.

Change history

17 April 2018

Due to a tagging error, two authors were incorrectly listed in indexing systems. Brook W. Cunningham should be B.A. Cunningham and Mark W. Yeazel should be M.W. Yeazel for indexing purposes.

References

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. [Webpage]. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health. Accessed 6/14. 2017.

2014 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015.

Committee on Lesbian G, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine.

Lim FA, Brown DV, Jr, Justin Kim SM. Addressing health care disparities in the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender population: a review of best practices. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(6):24–34; quiz 35, 45.

van Ryn M, Burgess D, Dovidio J, et al. The impact of racism on clinician cognition, behavior, and clinical decision making. Du Bois Review. 2011;8(1):199–218.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press; 2002.

Morrison M, Morrison T. Sexual Orientation Bias Toward Gay Men and Lesbian Women: Modern Homonegative Attitudes and Their Association With Discriminatory Behavioral Intentions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2011;41(11):2573–2599.

Cooper L, Roter D, Carson K, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–987.

Dovidio J, Kawakami K, Johnson C, Johnson B, Howard A. On the nature of prejudice: automatic and controlled processes. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1997;33:510–540.

Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238.

Sabin JA, Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):988–995.

Hafferty FW. Beyond curriculum reform: confronting medicine’s hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 1998;73(4):403–407.

Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43(4):356–373.

Vela MB, Kim KE, Tang H, Chin MH. Innovative health care disparities curriculum for incoming medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1028–1032.

Brown B, Heaton PC, Wall A. A service-learning elective to promote enhanced understanding of civic, cultural, and social issues and health disparities in pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(1):9.

Moss-Racusin CA, van der Toorn J, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Social science. Scientific diversity interventions. Science. 2014;343(6171):615–616.

Phelan SM, Puhl RM, Burke SE, et al. The mixed impact of medical school on medical students’ implicit and explicit weight bias. Med Educ. 2015.

van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical School Experiences Associated with Change in Implicit Racial Bias Among 3547 Students: A Medical Student CHANGES Study Report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1748–1756.

Kim D-Y. Voluntary controllability of the Implicit association test (IAT). Soc Psychol Q. 2003;66(1):83–96.

Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97(1):17–41.

Alwin D. Feeling thermometers versus 7-point scales: Which are better? Sociological Methods and Research. 1997;25:318–340.

Hafler JP, Ownby AR, Thompson BM, et al. Decoding the learning environment of medical education: a hidden curriculum perspective for faculty development. Acad Med. 2011;86(4):440–444.

Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. J Consult Psychol. 1960;24:349–354.

Rezaei AR. Validity and reliability of the IAT: Measuring gender and ethnic stereotypes. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(5):5p.

Williams DR, Rucker TD. Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;21(4):75–90.

Seifer SD. Service-learning: community-campus partnerships for health professions education. Acad Med. 1998;73(3):273–277.

Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1182–1191.

Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977.

Burke SE, Dovidio JF, Przedworski JM, et al. Do Contact and Empathy Mitigate Bias Against Gay and Lesbian People Among Heterosexual First-Year Medical Students? A Report From the Medical Student CHANGE Study. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):645–651.

Sanchez NF, Rabatin J, Sanchez JP, Hubbard S, Kalet A. Medical students’ ability to care for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered patients. Fam Med. 2006;38(1):21–27.

Pettigrew T, Tropp L, Wagner U, Christ O. Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35(3):271–280.

Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38(6):922–934.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Phelan is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (award no. K01 DK095924). Other support for this research was provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (award no. R01 HL085631). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders played no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Phelan, S.M., Burke, S.E., Hardeman, R.R. et al. Medical School Factors Associated with Changes in Implicit and Explicit Bias Against Gay and Lesbian People among 3492 Graduating Medical Students. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 1193–1201 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4127-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4127-6