Abstract

This chapter analyses the motives behind emerging organic food consumption in urban Vietnam. By outlining the influences on Vietnam’s organic sector through corporate and foreign aid actors and a governmental emphasis on productivity-oriented agriculture and overall food security, it provides a wider frame to understand the space in which consumers of organic food manoeuvre. Contemporary concerns over the health implications of food safety, regarded as the externalities of a modernising local agri-food system, appear as a strong motivator for buying organic food. Moreover, organic food consumption proved to be telling of wider insecurities regarding the responsibility between individuals, state and market in providing safe food. With organic food being a high-priced niche, eating safe becomes an issue of widening social inequality.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Declared organic food is a rather new phenomenon in Vietnam and constitutes a dynamic and high-priced niche market in the country’s urban centres. The emergence of organic sectors in the Global North—where the majority of research on organic consumption has been focused (Grosglik 2016)—has often been associated with wider societal movements for the environment (Johnston et al. 2009; Barendregt and Jaffe 2014; Poulain 2017). Yet while the organic niche in Vietnam could at first sight look like yet another local manifestation of a global trend towards ‘green’ ethical consumption, it has to be contextualised locally and historically in order to comprehend the underlying societal processes and drivers. Consequently, this chapter deals with the question of how the emergence of an organic sector can be understood within broader dynamics and discourses in the contemporary Vietnamese food systemFootnote 1 and the interplay of market, state and individuals.

This chapter will show how both the historical emergence of declared organic farming in Vietnam as well as the motives for consuming organic food prove to be different from developments of organic markets elsewhere. Organic demand and supply in current-day Vietnam must be viewed in light of the trajectories of the country’s food system and the actors operating within it. The current state of the food system is shaped by a variety of food safety issues which have led to an increased public awareness of and desire for safe food options, with organic food being one such choice. Not only is organic food consumption in the case of Vietnam revealed to be deeply intertwined with such omnipresent food safety concerns, it also illustrates broader insecurities over questions of responsibility in shifting relations between consumers, the market and the state. The at-times conflicting interests of these actors within the organic sector must therefore be seen against the backdrop of emerging neoliberal discourses of free trade, choice and responsible individualism with the simultaneous continuing presence of a strong state.

By zooming in on the organic niche market of Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), this chapter is specifically interested in the debates around trustworthiness, certification and responsibility regarding organic production and consumption, as they are inherently about power structures and relations between state, society and market. The aim of this chapter is thus to unravel how contemporary consumer discourses are reflected both in the structure of the organic sector and in perceptions and agency of urban organic food consumers, as well as in concomitant food safety discourses.

Based on field research conducted in Vietnam’s urban metropolis of HCMC between 2015 and 2017, the data for this chapter is composed of qualitative interviews, participant observation in organic food outlets, insights from a research workshop on food safety with Vietnamese social-science students that was co-organised by the author, as well as the latest agricultural restructuring plan and media research on organic developments in Vietnam. Coming from the interdisciplinary field of development studies, this research focuses on the local embeddedness of structural (political and corporate) powers, on inner-societal as well as global imbalances and specifically on perspectives on inequalities in relation to food.

The chapter starts with background information on recent trajectories around the food system as well as consumer discourse in Vietnam, followed by an overview over the emergence of the country’s organic sector contextualised within global trends around organic production. The empirical findings on organic consumption are then discussed in the context of current food concerns and a neoliberal discourse on individual responsibility of food care.

Food in (Urban) Vietnam

A System in Transition

The rapid transformation of Vietnam’s food system in the past 30 years can only be understood in the context of the market reforms of Đổi Mới and its succeeding economic and societal transformations (see Ehlert and Faltmann, this volume). Agricultural and societal developments that accompanied the economic reforms in turn mark the needed contextualisation for shifts in provisioning and consumption patterns and discourses around food that are at the centre of this chapter.

Since the former socialist planned economy began transforming towards a decentralised market economy, starting in the late 1980s (all the while remaining under communist one-party rule), the food situation in Vietnam changed fundamentally as well. While centrally planned agriculture, state-managed shops and ration coupons for scarce food supplies characterised the years before the economic reforms (Figuié and Moustier 2009), there are now growing, yet unequally accessible, foodscapes of plenty (Figuié and Bricas 2010, 181). Standards of living have risen and global cultural and corporate influences have entered the country, including its food environments, for example, with foreign restaurants, fast food chains, supermarkets and convenience products (Pingali 2007; Figuié and Moustier 2009; Bitter-Suermann 2014).

Structurally, rural-urban migration and changing social structures related to industrialisation and urbanisation processes led to an increased gap between food producers and consumers. Direct contact with farmers and traceability of food are often no longer given, especially in urban contexts, constituting the ‘distanciation’ of a food system (Bricas 1993).

On the food production side, dynamics have been strongly shaped by the so-called Green Revolution, an agricultural turn towards agrochemicals, mechanisation and high-yielding crop varieties (Parayil 2003, 975). Agricultural intensification was pursued both in North and in South Vietnam since the 1960s (Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013, 83). Yet due to the disruptions of the Second Indochina War, the Green Revolution in Vietnam fully picked up in the late 1970s after 1975’s end of war and the country’s unification, thus later than in many other Asian countries (Tran Thi Ut and Kajisa 2006). Among other measures, pesticides and chemical fertilisers achieved strong productivity gains while also leading to growing production costs, structural dependencies and unwanted side effects both in terms of human health and the environment (Carvalho 2006; Scott et al. 2009; Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013). Moreover, land use conversions related to urban sprawl as well as small farm sizes have resulted in pressure on the environment, productivity of land and farmers (Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013). In numerical terms, agriculture has seen a 10 per cent annual increase in the use of chemical fertilisers between 1976 and 2009 (Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013, 84). The excessive application of agrochemicals is said to have spiked since the liberalisation of the agrochemical input market in the late 1980s and continues to be maintained in part by illegal imports of now forbidden substances (Pham Van Hoi 2010; Tran Thi Thu Trang 2012). Related food safety crises linked to high agrochemical residues in produce have occurred since the 1990s (Nguyen Thi Hoan and Mergenthaler 2005; Simmons and Scott 2007; Scott et al. 2009). Some view the over-application of chemicals in agriculture as a coping mechanism for Vietnamese small-scale farmers who attempt to increase outcomes and profits to ensure viability in the face of land concentration, class differentiation processes and economic pressures related to industrial agriculture (Tran Thi Thu Trang 2012; Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013). In a similar vein, the establishment of ‘safe’ food labels, as is described below, has been identified as market- and demand-oriented, rather than focusing on issues of farmers’ subsistence or food sovereignty (Scott et al. 2009, 72). Government attempts to regulate and restrict agricultural inputs have included the ban of certain agrochemical substances as well as the governmental establishment of a ‘safe’ food label in the 1990s guaranteeing controlled use of agrochemicals. Yet little profitability for farmers meant a low market share of ‘safe’ vegetables, and the absence of consequences for producers in cases of non-compliance led to scepticism among consumers (Moustier et al. 2006). As a result, the programme was discontinued after 2001 (Moustier et al. 2006) and succeeded by VietGAP, the Vietnamese version of a globally prevalent standard of ‘good agricultural practice’ under governmental decreeFootnote 2 (Nicetic et al. 2010). Whereas VietGAP products are sold in supermarkets, many supermarket chains also offer their own ‘safe’ food labels (Moustier et al. 2010). Generally, all vegetables sold in modern retail outlets require a certification that they conform to the government’s safe vegetable production guidelines (Wertheim-Heck et al. 2015, 98).

The described transformations in Vietnam’s food system are further embedded in and structured by governmental modernisation and formalisation approaches. In terms of food production and the organisation of agriculture, the Vietnamese government shares the paradigm of the Green Revolution that growing populations can only be fed through agricultural intensification (Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013, 88). In line with this, the government’s 2017–2020 agricultural restructuring plan aims for large-scale production areas and a decrease of the labour proportion in the agricultural sector (MARD 2017). Modernisation and formalisation attempts also structure the food retail system through supermarket expansion and the reorganisation and reduction of often informal wet markets (Wertheim-Heck et al. 2015) which targets safer food provisioning through the role of supermarkets in private safety management systems and hygiene standards (Wertheim-Heck 2015, 4). Relatedly, on the consumption side, governmental modernisation efforts include the promotion of food shopping in supermarkets and in particular of VietGAP products (Nicetic et al. 2010) as opposed to wet market shopping.

Overall, as recent decades have seen transformations in the economic and agricultural system as well as in the societal structure, availability of and access to food offerings has undergone enormous change and diversification. Within the described plethora of food supply options—some established, some of a more recent nature—people manoeuvre their way to their personal consumption decisions and habits, a task that is aggravated by concerns regarding the safety of food. It is in this setting of ‘distanciation’, differentiation and scepticism that a newly emerging niche market for organic food has emerged, a niche that is indicative of broader developments not only within the country’s food environment but also of societal concerns around food as will be elaborated in the course of this chapter.

Consumer Discourse in Vietnam

In order to comprehend the trajectories of the organic sector and the perspectives of organic food consumers in contemporary urban Vietnam, discursive changes in terms of corporatisation and consumption in the country’s recent past prove to be illuminating. In the transition from pre-reform central planning to post-Đổi Mới liberalisation, the country has seen a marketisation and globalisation of its economy which has been intertwined with the emergence of what could be referred to as neoliberal logics (Nguyen-vo Thu-huong 2008, xi). In keeping it with Schwenkel and Leshkowich (2012), neoliberalism in this chapter is not understood as a uniform project but rather as a “globally diverse set of technical practices, institutions, modes of power, and governing strategies … that continually work to reframe and at times reconfirm neoliberal technologies of mass consumption, acquisition of wealth, moral propriety, regimes of value, and systems of accountability” (Schwenkel and Leshkowich 2012, 380f.). Acknowledging the historical and cultural particularities of such institutions and strategies (Schwenkel and Leshkowich 2012, 380) also allows us to look for neoliberal logics within an officially socialist one-party state. Part of neoliberal ideologies emerging in the globally connected market in Vietnam have been discourses on free trade, privatisation as well as freedom of choice (Nguyen-vo Thu-huong 2008, xiii; Schwenkel and Leshkowich 2012, 382). Meanwhile, a generalised understanding of post-Đổi Mới Vietnam as following a ‘neoliberal’ blueprint based on the model of Global North societies can be contested on various grounds: within a market economy with a socialist orientation, the Vietnamese state has remained politically and economically all-encompassing, as well as the biggest stakeholder in the Vietnamese economy (Nguyen-vo Thu-huong 2008, xix). More generally, neoliberal practices intersect with and at times contradict continuing socialist political visions and illiberal practices (see Gainsborough 2010; Schwenkel and Leshkowich 2012). Thus, increasingly prevalent notions of private, individualised choice and self-interest exist alongside a strong state that continues to govern self-interests from the distance, which has been coined as “socialism from afar” (Ong and Zhang 2008, 3, for the case of China).

Since market liberalisation, discourse on consumption in Vietnam has seen a vigorous turn from governmental condemnation of conspicuous consumption as a threatening form of capitalist imperialism (Vann 2005, 468) towards an insistence on the neoliberal liberty of choice for individuals in their role as consumers or entrepreneurs (Nguyen-vo Thu-huong 2008, xiii). Thus newly ‘discovered’ consumers now find themselves in the position to choose from diversified markets with the corporate promotion of modern consumption (Ehlert 2016). The notion of consumer choice in turn also includes a moral imperative of making the ‘right’ choice (Parsons 2015). Thus as responsible neoliberal citizen, the individual is expected to be in charge of his or her well-being and health, a discourse referred to as ‘responsible individualism’ (Parsons 2015, 1). This is of particular interest for this chapter in the field of food and questions of the responsibility of healthy and safe food choices.

As has been noted, these neoliberal tendencies among trajectories of corporatisation and responsible individualism are embedded in at-times conflictive state powers, thus Vann (2005) speaks of “incomplete neoliberal projects” (Vann 2005, 484). As such, contemporary Vietnam evinces a plurality of governing and economic logics of which neoliberal ideologies are one component (Schwenkel and Leshkowich 2012), producing its own kinds of particularities, dynamics and challenges between state, emerging markets and consumers.

Development of Organic Sectors in Global and Local Contexts

Before diving into the specific developments and synergies of the organic sector in Vietnam, a look at organic in global contexts will establish background information against which to understand the specifics of Vietnam’s situation.

Organic in Global Contexts: A Brief Overview

Organic food production in the broadest sense entails a mode of farming based on the principles of health, ecology, fairness and care (IFOAM 2005). As an integrated farming approach, it aims to maintain the vitality of plants, soils, animals and human health and make use of on-farm and local resources (Vogl et al. 2005, 6; Scott et al. 2009, 63). Explicit organic farming ideas emerged in the early twentieth century in the Global North as a critique of the effects of petrochemical agricultural inputs on the environment as well as human health (Scott et al. 2009, 63). Throughout the twentieth century, organic farmers in many countries began to organise themselves through associations, within which organic standards were agreed upon democratically (Vogl et al. 2005, 9). The certification of organic products then was a response to growing citizen interest in organic food in the 1960s and 1970s (Scott et al. 2009, 63). The early emergence of organic markets and consumer interest in organic food in the Global North were often related to broader environmental movements concerned with eco-central societal transformations towards sustainability and systemic change (Barendregt and Jaffe 2014, 5). For instance, the USA of the 1960s witnessed an organic food movement striving for small-scale food production, ecological responsibility and community engagement (Johnston et al. 2009, 510). In Western Europe, organic consumption gained considerable momentum as part of a wider environmental movement against the ecological impacts of industrialised food systems in the 1970s, itself originating in anti-establishment student uprisings (Poulain 2017, 66). While eating organic in these contexts was often embedded in environmental activism and attempts to establish an alternative to the conventional food system, large parts of the organic sector in North America and Europe have transformed into what Johnston et al. (2009) have termed the ‘corporate-organic foodscape’. The term refers to the institutionalisation and corporatisation of organic agriculture, resulting in often large-scale industrial organic farms and their integration into global commodity chains (Raynolds 2004). This integration of organic farming into corporate and globe-spanning food systems and commercial consumption since the 1990s (Johnston et al. 2009) was in line with wider global trends emphasising consumerism and individual responsibilisation of health and food choices (Parsons 2015; see Ehlert and Faltmann, this volume). As organic farming is considered an alternative to the agricultural model of the Green Revolution (Vogl et al. 2005, 6), critics point out that this corporatisation, institutionalisation and the global transport of organic goods stands in contrast to the social, ecological and anti-institutional ideals of the original organic movements (Goodman and Goodman 2001; Guthman 2004).

The transformations in the organic sector are also reflected in the history of organic standards: while associations of organic farmers in many world regions followed their own private standards until the 1990s, organic agriculture has since then seen increasing standardisation and regulation (Vogl et al. 2005). Thus nowadays, organic can comprise a range of practices: small-scale farming without synthetic inputs following organic principles potentially without explicitly being termed organic, often referred to as ‘organic by default’ (Vogl et al. 2005, 10) or various forms of certified organic agriculture following specific guidelines (Simmons and Scott 2008, 3f). The latter can be differentiated between internally carried out certification processesFootnote 3 or external certification by authorised bodies. Such authorising bodies can be state-centred,Footnote 4 or private third-party certification bodies (Boström and Klintman 2006). This formalisation of organic agricultural practices, intended for consumer and producer protection and the regulation of trade (Vogl et al. 2005), at the same time poses financial and bureaucratic burdens for farmers through cost-intensive certification processes which have to be renewed periodically (Johnston et al. 2009). Moreover, with the development of certified organic farming being rooted in the Global North, structural imbalances in global organic supply chains between Global North retailers and suppliers on the one and Global South producers on the other hand are problematised as much as the question of appropriateness of organic standards developed in the Global North for ecological conditions in the Global South (Scott et al. 2009, 68).

Nowadays, in many countries of the Global North one can find organic food on the shelves of transnational supermarket chains as well as in less institutionalised and rather bottom-up forms such as Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) or self-organised food cooperatives (Johnston et al. 2009). The range of organic offers is also reflected in the clientele whose spectrum ranges from individualised middle-class organic lifestyles often interwoven with means of distinction (Barendregt and Jaffe 2014) to more politicised and collective forms of alternative food initiatives (see Hassanein 2003; Little et al. 2010; Oliveri 2015). Thus, while the described early organic niches were associated with social movements concerned with environmental sustainability, this ethicopolitical factor has not been obtained in all cases. Even more, the market logic behind the idea of contributing to environmentalism through consumption inherently contrasts the mentioned more radical environmentalist approaches to systemic change in the 1960s and 1970s (Barendregt and Jaffe 2014, 5f). Nontheless, the perception of organic farming as environmentally friendly still constitutes a major motivation for organic consumption (Seyfang 2006; MacKendrick 2014). Despite the increasing industrialisation, corporatisation and depoliticisation of large segments of Global North organic sectors, governments and organisations from the Global North often justify their support and establishment of organic initiatives abroad with ethical ideas of environmental sustainability and climate change mitigation -as is the case in Vietnam.

Foreign Influences Behind Vietnam’s Organic Development

Whereas the export of organic products from Vietnam to markets with strong purchasing power (such as Europe and the USA) has been in existence since the 1990s (APEC 2008), organic production for the domestic market is rather new and still scarce. Organically certified exports include commodities ranging from tea and coffee to rice, shrimp and fish, and make up around 90 per cent of organic production in the country (Simmons and Scott 2008, 2ff). Often with a particular emphasis on low costs of labour and production, (foreign) corporate interest in the export of organic agricultural products from Vietnam is on the rise (see Biz Hub 2016; Viet Nam News 2017a).

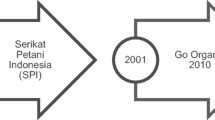

Pioneering in the field of organic farming for a Vietnamese market was CIDSE, an umbrella organisation of Catholic development agencies, which supported the launch of the first organic production project in 1998 (APEC 2008). In the following year and with some funding from international NGOs, the private company Hanoi Organics of two Vietnamese and a Dutch person began linking organic producers in the outskirts of the capital with Hanoian consumers (IFOAM 2003; APEC 2008). Between the enterprise’s initiation and the lapse of certification due to financial difficulties in 2004, ‘Hanoi Organics’ was certified by ‘Organic Agricultural Certification Thailand’ (Moustier et al. 2006, 301). Between 2005 and 2010 a project by the Danish NGO ‘Agricultural Development Denmark Asia’ (ADDA) in cooperation with the ‘Vietnam National Farmer’s Union’ (VNFU), funded by the ‘Danish International Development Agency’ (DANIDA), also aimed for the production and promotion of organic agriculture in Vietnam and developed an internal certification system (APEC 2008; Nguyen Sy Linh 2010, 128; Whitney et al. 2014). A further actor is the Belgian NGO ‘Rikolto’ (formerly VECO) that carries out activities that promote sustainable agriculture in Vietnam through projects with farmers as well as the initiation of an online platform ‘Safe & Organic Food Finder’ in Hanoi (VECO 2016). Meanwhile, organic production for export markets in many cases enjoys foreign support, such as in the case of an organic tea project in the early 2000s in Northern Vietnam, funded by the New Zealand government, which aimed for poverty reduction among the participating smallholders (APEC 2008). Moreover, there exist different organic shrimp projects in Ca Mau Province which were assisted by the German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety and by the Netherland Development Organisation, projects whose support is justified with their environmental benefits, developmental capacities and climate change mitigation potential (Omoto 2012; Brunner 2014; Viet Nam News 2014; Baumgartner and Tuan Hoang Nguyen 2017).

Such initiatives reflect larger paradigm shifts in the dissemination of agricultural models by Global North donors whose promotion of sustainable farming has at times replaced former support for Green Revolution agriculture in the name of productivity gains (Conway and Barbier 1990).

Such shifts have also been observed on a corporate level: whereas agricultural inputs in line with the Green Revolution have a history of strong corporate support, the significant involvement of corporate—particularly supermarket—interest in the purchase of organic products is a more recent phenomenon and one that enhances corporate structural power within the organic segment and its commodification (Scott et al. 2009, 85).

In sum, many initiatives involved in the development of the organic sector in Vietnam are foreign-led. Organic initiatives by foreign NGOs and development agencies often have an explicit emphasis on the environmental benefits and developmental mights of organic farming. Operating modes vary as some organic initiatives establish rural-urban producer-consumer links, thus focusing on organic food within the domestic context whereas other Global North-led projects establish certified organic production for export markets, thus bearing the implicit element of international market development. Moreover, Vietnam increasingly attracts corporate interests to produce organic products for export markets. At the same time governmental support for an organic sector for the Vietnamese market has been peripheral in the past, as will be discussed now.

Vietnamese Perspectives on Organic Agriculture

As regards the Vietnamese government, written national organic standards were introduced in 2007 (Scott et al. 2009, 72), yet no regulation on organic production and trade is in place (Nguyen Sy Linh 2010, 128). With respect to certification, there is neither a domestic third-party certification organisation (Ngo Doan Dam n.d., 1; Moustier et al. 2006, 300) nor are there governmental plans to initiate a national organic certification body (interview with staff of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD), 10/2016). Thus, if desired, certification needs to be sought from abroad, making the process lengthy as well as costly and not accessible for small-scale production. Unlike, for example, in neighbouring Thailand where the national government plays an active role not only in the promotion but also the certification of organic agriculture, Vietnam’s organic sector is predominantly driven by the private sector and foreign NGOs, as well as by some government-affiliated organs such as the Farmer’s Union and local government authorities (Scott et al. 2009, 82). The question of driving forces behind organic sectors also reflects in civil societyFootnote 5 involvement and public discourses about organic food and its production. The wider spectrum of actors such as within alternative agriculture movements both in Thailand and in Indonesia have resulted in debates around corporate control of the organic sector in these countries (Scott et al. 2009, 84). In Thailand there is an established local food sovereignty initiative which utilises organic farming and local marketing also as a means of resistance against structural dependencies and ecological destruction as a consequence of industrialised agriculture (Heis 2015). In Vietnam, where the organic sector is mostly shaped by corporate and foreign influences and according to the logic of the market, such critiques of corporate control or the establishment of grassroots organisations striving for food sovereignty are weak or non-existent (Scott et al. 2009). Despite issues of environmental pollution (see Pham Binh Quyen et al. 1995; Pham Thi Anh et al. 2010) and even though the effects of climate change on agriculture are beginning to be noticeable (Fortier and Tran Thi Thu Trang 2013), widely formalised environmental movements—of which organic advocacy could be an element—have not been established in Vietnam. Of course, this must also be seen in the socio-political context of tightly controlled formal civil society organisations (Wells-Dang 2014). While civil society action against environmental pollution certainly exists (see Tran Tu Van Anh 2017), an occurrence in 2016 made obvious the often restricted space for organised politicised expression of opinion. After a mass of fish dying on Vietnam’s central coast related to a Taiwanese steel factory and people in major cities going to the streets against the slow government response towards this pollution scandal, the initiating protests were suppressed (Radio Free Asia 2016).

Meanwhile, there could be a change in direction in the attention organic farming is receiving from the government: at an international forum on organic agriculture in Vietnam in 2017—co-organised by MARD—Prime Minister Nguyễn Xuân Phúc presented the increasing demand for organic products as a chance for development of organic farming in the country. Phúc thus called for the adoption of global organic standards in Vietnam, seeing the target groups among high-income domestic groups as well as in global organic markets. At the same event the Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development pointed out that few Vietnamese businesses were internationally certified organic, increasing mistrust towards their organic products (Saigon Times 2017; Vietnam Economic News 2017; Viet Nam News 2017b). Moreover, the country’s newest agricultural restructuring plan—besides mentioning large-scale production and labour productivity increase—now includes the encouragement of clean and organic agriculture (MARD 2017). Thus while such calls for organic farming are new on the side of the Vietnamese government, food safety and health (Scott et al. 2009, 84ff) as well as the promotion of VietGAP standards and the country’s overall modernisation, industrialisation and intensive farming for food security remain the overall aim (see Gorman, this volume).

In the Vietnamese discussion on the organic food sector, a clear definition or protected terminology is often missing. Media articles frequently use the terms ‘organic food’ (thực phẩm hữu cơ) and ‘safe food’ (thực phẩm an toàn) interchangeably (Simmons and Scott 2008, 4), a confusion that, coupled with the novelty of marketed organic food, impacts consumers’ perceptions of the concepts as well (Moustier et al. 2006, 300; Simmons and Scott 2008, 4). During the student workshop conducted in the course of research for this chapter, the terms ‘safe’ and ‘organic’ food were also discussed interchangeably by the Vietnamese students and without differentiation of the particularities in production (field notes, 08/2017). Such differentiation is essential though, since the requirements for organic farming forbid the use of chemical inputs altogether whereas in farming for marketed ‘safe’ vegetable production such as VietGAP, the moderate use of certain chemicals and fertilisers is permitted (Simmons and Scott 2007, 23). Despite this difference, the promotion and sale of products as ‘organic’ while originating from so-called safe food production has at times been observedFootnote 6 (Moustier et al. 2006; field notes, 11/2015). Regarding financial accessibility, the prices for organic products in Vietnam are substantially, at times in multiples, above the market average of comparable non-organic products (Tran Tri Dung and Pham Hoang Ngan 2012, 1). One reason for the very limited domestic market for organic products (Scott et al. 2009, 72) could lie in this premium price for organic food, whereas another inhibition could lie in the low, yet rising, share of organic agriculture among Vietnam’s total agricultural land.Footnote 7 Besides the growing but small externally certified organic production, there are only a few internally certified initiatives which link farmers with Vietnamese consumers, concentrated mostly around Hanoi (PGS IFOAM, n.d.).

In line with the weak ties to civil society and (thus far) low governmental attention, Vietnam’s organic sector leads a niche existence, yet it is gaining momentum. Thus, if the newest governmental statements mark a paradigm shift towards growing support for alternative agricultural systems or are merely lip service remains to be seen. With all this in mind, what does the organic niche market look like in urban Vietnam and how does it relate to or contrast with prevailing consumer paradigms and the motives of foreign and domestic support for Vietnam’s organic sector?

HCMC’s Organic Food Sphere

In HCMC, the attentive observer will first notice the corner shops with green signs advertising ‘organic’ food scattered across the city, or more precisely across certain districts. Moreover, a major street in the city centre hosts a large organic store selling a variety of imported organic products, predominantly from Germany, as well as produce that is not actually organic but VietGAP certified (field notes, 08/2017). Yet organic consumption opportunities do not end there. Besides the array of shops, there exists a range of organic delivery services, artisanal cosmetic brands and air-conditioned organic juice-shops, offering their services in the more wealthy districts of the city or advertising them at events and on social media. A range of occasional markets enabling consumers to purchase food directly from farmers or from small businesses have become increasingly popular. Among signposted organic produce on offer in HCMC, certified organic production is the exception to the rule. At the time of research, there were three shops offering organically certified fruits and vegetables of Vietnamese origin in HCMC, whereas other enterprises labelled ‘organic’ follow organic production without certification and yet others sell certified ‘safe’ rather than ‘organic’ produce (field notes, 2015–2017; online research, 02/2017). Moreover, some of the enterprises have a short half-life with many having disappeared within the three years of field research. Organic food production in a broader sense also extends into homes and event venues: small plots of land can be rented in a private urban garden area doubling as vegetable fields, leisure venue and setting for nature education courses for children (Word Vietnam 2016; field notes, 07/2016). Also less spacious options for chemically untreated food are being utilised by many urban inhabitants in the form of smallest-scale home cultivation of sprouts, herbs or vegetables (see Kurfürst, this volume). Such practices of vegetable cultivation (at home or on a rented plot) could be subsumed under organic food consumption and at times are viewed as such. Yet this chapter examines organic consumption in a more narrow sense in outlets which specifically market organic products. In such corporate settings where citizens manoeuvre as consumers, trust and knowledgeability are negotiated very differently than in (semi-)private settings. Thus, what drives people to opt for organic food in their shopping will be explored next.

Organic Food Consumption in HCMC

Moving from the structural aspects and macro-level actors within Vietnam’s organic sector to the perceptions and agency of individuals, this section zooms in on consumers of organic food in HCMC. The aim of the analysis of empirical data on organic food consumption is to compare and contrast the narratives of the interviewees with the structures and trajectories of the country’s (organic) food system as it exists today.

Before going into the underlying motivations of customers and entrepreneurs of organic food, these will be briefly portrayed. The basis for the portrayal are 13 interviews with customers of an organic shop in the city centre, as well as 2 interviews with organic entrepreneurs. One of the entrepreneurs, whom I will refer to as Hoa,Footnote 8 is the owner and founder of a number of organic shops—one of which was a site for the customer interviews—that sell organic produce from affiliated farms within Vietnam as well as certified imported organic goods. At the time of the interviews, the farms were in the process of becoming certified as some of the first for the Vietnamese market. The other entrepreneur, Minh, is the founder of a service delivering uncertified organically produced fruits and vegetables from his farm to customers in the city centre.

All but one of the interviewees were women, a gender imbalance that complied with general observations in food outlets, whether organic shops, markets, or supermarkets in the city. Although increasing participation of men in food shopping has generally been observed, especially in more aspirational urban lifestyle places such as supermarkets, food shopping is still often considered a predominantly female task (Wertheim-Heck and Spaargaren 2016). On closer examination many of the female customers also turned out to be mothers or other caretakers of young children—a characterisation shared by the founder of the organic delivery service: Minh estimated that 95 per cent of his customers were mothers of babies, feeding organic produce to their children while often not consuming organic themselves (Interview, 10/2015). Age-wise the interviewed customers ranged from early 20s to mid-60s, with mothers in their 30s most strongly represented. Except for one older lady, the interviewees were all in employment or university students, an observation very much in line with the advice of the shop’s staff for the author to come after 5 p.m. in order to encounter respondents after office closing hours. Most interviewees were either in the process of acquiring higher education degrees or working in occupations requiring such, indicating a high level of education among the respondents. The often exceptionally high English skills of many of the customers—half of whom preferred to lead the interviews in EnglishFootnote 9—furthermore hinted at a potentially private education and/or an international work environment. When asked to portray the company’s customer base, one of the organic entrepreneurs described managers or business owners, having middle to high incomes, with high being estimated at USD 1000 per capita and month. Yet, people with lower incomes were not ruled out as potential customers: “Low income means it’s around USD 500 per month, it’s okay. But if you just can earn USD 50 or 100 per month it’s difficult [to buy organic]” (Interview, 10/2015). Compared to Vietnamese average incomes,Footnote 10 the estimated ‘low’ monthly income of USD 500 would still position the customers of this business well above the national average.

The common view that consumers of organic food necessarily have high incomes was challenged by the other interviewed entrepreneur who did not see income as the major factor among organic customers:

Mostly many people think that the rich people have money to buy organic products. But I think it’s not good based on, you know, I think many people, many customers they are still young. Students and young people. I think that they are not rich people but they still pay for organic products because they care about their health, their family health, future also …. But mostly people are medium, I mean average income. (Interview 01/2016)

Besides the income aspect the quote addresses a number of crucial aspects of organic food consumption, with the portrayal of consumers not only as young and often educated but also united in their concern for health, an observation that will be contextualised further on. While far from being a homogenous group, many of the interviewed customers did share certain characteristics in terms of gender, education, income as well as their motivations for organic consumption.

Organic Consumption for Environmental Concerns?

As elaborated previously, environmental considerations as well as concerns for the well-being of farmers or the future of the agricultural system were and are often part of the motivation for organic consumption elsewhere. Some of the (limited) existing research on the consumer side of organic food in Vietnam has also pointed out environmental concerns as one of a range of reasons for organic consumption (Ho Thi Diep Quynh Chau 2015; VECO 2016). Yet when asked about their motives for organic consumption, such environmental concerns were not brought up independently as a reason for choosing organic by any of the costumers interviewed by the author. Interestingly, a baseline study among vegetable consumers in Hanoi carried out came up with contrasting results. According to the survey, the main reasons for buying safe or organic vegetables were health (91 per cent) and environmental protection (38 per cent), followed by better taste (20.5 per cent) (VECO 2016, 2).Footnote 11 Whereas health in this survey emerged as the leading priority, which will be discussed later on, it is striking that one third of the survey respondents stated environmental concerns as a motivation for organic consumption whereas this aspect was not brought up once by the interviewees of the authors’ research. The difference is even more remarkable as the interviewee demographic of both research projects was similar, comprising mostly female, middle to high income, respondents (VECO 2016, 1). A quantitative survey among consumers in different food outlets in HCMC also showed a relation between environmental concern and the intention to purchase organic food (Ho Thi Diep Quynh Chau 2015). Here, contrasting the methodologies of quantitative and qualitative research has explanatory potential: in the case of the baseline study a structured questionnaire provided predetermined answers, stating environmental protection as one potential reason for organic consumption, while the qualitative open-ended questions underlying this research did not offer such predetermined response categories. Expecting and assuming that environmental concerns are a motive to purchase organic food might be a predetermined notion shaped by a Global North conception of organic consumption which potentially diverges from the Vietnamese context. Hence, the open-ended character of the interviews for this study allowed for exploring the interviewees’ subjective sense of and views on organic consumption of their own accord, potentially diverging from the researcher’s personal associations with and knowledge of organic farming.

The semi-structured interviews underlying this chapter also asked if consumers paid attention to the food’s origin when buying organic. In the cases in which origin was stated to be of importance at all, it was referred to in terms of product safety or international food standards in the countries of origin. Meanwhile, the issue of carbon footprints related to potentially long transport distances was not mentioned as a reason to pay attention to origin. While the reduction of environmental impact through ‘local’ consumption is often a component in organic consumption (see Brown et al. 2009), food miles were not an aspect that was expressed by any of the interviewed consumers.

As vegetables and, to a lesser degree, fruits—which happened to be from organically managed farms within Vietnam—were among the most purchased goods among the interviewees, the factor of food miles might simply not have been of any personal relevance here. At the same time, the origin of the mainly imported processed goods on offer, for which the question of environmental costs of transportation would apply, was also not brought up by the interviewees.

Entrepreneur Hoa stressed having consumer education on sustainable agricultural development and the environmental benefits of organic agriculture on her agenda, which unearthed a discrepancy between the entrepreneur’s assessment of her customers’ environmental aspirations and the views the customers themselves voiced. While Hoa assumed that her customers “think that if they buy organic they can contribute to agricultural development in Vietnam” (01/2016), such a motive was not named once by her customers.

The absence of environmental concerns in the motivations of organic customers not only marks a contrast to the narrative of the Vietnamese organic entrepreneurs. It also differs from the motives behind early organic niche markets in the Global North which—as elaborated before—have been intertwined with environmental citizen movements. Moreover, the customers’ non-priority of environmental protection contrasts the foreign supporters of organic development in Vietnam who proclaim environmental benefits at the core of their support.

Health & Food Safety

Health concerns appeared as a central topic among the interviewed consumers with their own health as well as that of their families being stated as the number one reason to purchase organic. The main fear here was of the long-term effects from consuming chemically contaminated food, mostly vegetables and meat, resulting in cancer as one customer expressed:

I think organic food is very good for your health, sort of you can protect, avoid the cancer. So the organic food they don’t use too much chemicals so they are very good. (Interview, 10/2015)

To avoid chemically contaminated food, consumers would resort to organic products in the knowledge that chemical inputs were not utilised. Besides the general thematisation of chemical usage in farming, the widespread narrative of farmers spraying produce with certain chemicals that would make them grow unnaturally fast was also taken up by some of the interviewees. Thanh, 64 years old and regular customer at the shop, refers to this practice of growth acceleration: “I have a relative in the countryside, he told me that each two to three days people harvest chili, so horrible” (Interview, 10/2015). Organic vegetables on the other hand were believed to be grown slower and without such chemical enhancers. Besides the application of chemicals in farming, concerns regarding growth hormones in meat were also frequently voiced. Here a university student, shopping vegetables for her family, explained why she has been restricting her meat consumption:

Because I know it’s not good to eat because they have poison in the meat. It means that instead if you raise a pig or a buffalo you need about six months to grow it … and now usually they’re just three months I think and a few weeks before they sell for the meat company they will get food that helped the pig grow fast in two weeks. (Interview, 10/2015)

Generally, the interviews coincide with existing research stating an increasing demand for organic produce in Vietnam, especially for health reasons and among people with higher incomes (Moustier et al. 2006; Thien T. Truong et al. 2012). The centrality of the health factor in organic consumption in turn must be put in relation to the overall food safety situation in current Vietnam in which the fear of unsafe, health-damaging substances in food is very prevalent. Especially in urban settings where people rely on external and anonymous food supplies, the complexity and anonymity of the food chain is often cause for concern. Anxieties over the safety of food mainly focus on high agrochemical residues in vegetables (Moustier et al. 2006, 297; Mergenthaler et al. 2009a, 267; Pham Van Hoi 2010, 3) and antibiotic remnants in meat (Figuié and Moustier 2009, 213)—the same concerns that were also voiced in the interviews with the customers. Practices of fraud such as the selling of counterfeit and substandard products are another source of insecurity over unsafe food (Figuié and Bricas 2010, 181). Products with a particularly critical reputation are foods of Chinese origin (Mergenthaler et al. 2009b, 429) as they are said to be the target of overly chemical treatment and preservation as well as substandard controls (see Zhang, this volume).

Besides concerns over the quality of products, the interviewees’ concerns also related to questions of food hygiene in certain outlets. In general debates, food hygiene concerns in Vietnam predominantly concern street food or large-scale canteens, for example, in factories, some of which have been reported to produce cases of mass food poisoning (Viet Nam News 2016). While questions of hygiene of pre-cooked meals is less related to the purchase of organic foods for home-cooking, said concerns regarding certain food outlets did come up in the interviews in the context of food avoidance, proving to be of relevance for the customers.

The purchase of organic food was generally seen as the safe alternative to unsafe food. Meanwhile, customers’ explanations of organic farming varied widely, ranging from detailed knowledge about organic standards and practices to the more common description of organic farmers not using chemicals. In this regard, the internet was often named as the source of information on organic agriculture, yet the press as well as social media and friends played a role as information sources as well. It was also the recommendation of friends or internet research that led many of the customers to this specific shop, whereas others encountered it by chance. This customer, who is an employee at a bank and a mother of two children aged one and five, frequents the shop as the owner is her friend, whose information on organic farming she seems to trust:

The quality of these vegetables, when they grow, until they collect the vegetables in the field they control the quality from the company. And I know about it, because my friend [shop owner] told me personally. (Interview, 10/2015)

Others stressed that they could not be sure if the shop’s food was actually safe or not, yet believed in it “based on a feeling” (Interview, 10/2015). The element of uncertainty arose in a number of the interviews and was at times met with trial and error as Thanh describes:

We had food here several times as a trial. And then we stopped in short time because the food was so expensive, and we bought food in normal market for [a] meal … but we had [food] poison[ing]. Finally we use food faithfully in this shop …. I believe because no shop I can trust in like this shop. (Interview, 10/2015)

In this case it is not a general belief in the quality of organic food but trust in this very specific shop after trial and error and comparing it with another organic store which she found out to be better in advertisements than in reality.

Pivotal Moments Towards Organic Consumption: The Centrality of Responsibility

In addition to a general awareness of and anxieties towards food safety issues which could lead to the wish to consume organic food, some of the interviewees reported events that can be understood as pivotal moments or turning points towards organic consumption. For many of the interviewed mothers as well as for others in familial care-taking roles, this pivotal moment was the responsibility for small children. The wish to provide harmless and healthy food to the children was often expressed: “Sometimes I go to another organic shop to buy the same food [as in this shop] because now I have a child. My son is six months. Today is the first day of his weaning.” As Bich, regular customer, university lecturer and mother of two young children indicates here, the stop at the organic shop constitutes a task often in addition to regular grocery shopping which is done elsewhere. Moreover, opting for organic food on the first day of weaning suggests the importance put on the high food quality intended for the child from the very first bite. Thanh, who was accompanied by her four-year old grandson, depicted the interlaced events of expecting a baby in the family with a case of food poisoning, leading the whole family to change their consumption habits:

When my daughter was pregnant, I bought green cauliflower and water spinach and string bean, my daughter had these foods, and had [food] poison[ing]. So we decided that we just use the amount of food we can buy here, depending on our money. (Interview, 10/2015)

Regarding organic food for children it was noticeable that oftentimes due to financial reasons kids would be the only recipients of organic food in a household. “Because it’s high quality vegetables it’s also quite expensive. So just for my children” (Interview, 10/2015), Bich explains. Concomitantly, the choice of products in such contexts was often very selective, limited predominantly to vegetables and fruits for the children.

Going the extra length financially and by adding to the regular shopping routine in order to provide the family’s children with the perceived safest food not only indicates the weight that is put onto the children’s health. It also hints at a form of responsibilisation in which it is the task of the individual to protect the health of those unable to exercise choice by themselves, namely children.

The role of responsibility for the family’s health as a pivotal moment was not limited to the interviewed shoppers but also voiced by the organic entrepreneurs. Minh, founder of the organic delivery service started farming based on organic principles on family land in order to provide himself, his family and friends with healthy food: “Because I care [for] my health and [for] my family’s health. And I think some of my friends they need my products” (Interview, 10/2015), a decision that later evolved into a business. Organic entrepreneur Hoa explicitly described expecting a baby as the pivotal moment that drew her attention to the health aspects of eating:

So before 2013 I was not concerned about what I eat, I don’t care, I don’t know about organic. But when I was pregnant in the first 3 months I was sick, sickness of pregnancy, so I did not eat anything except raw vegetables. So whenever my mom or my husband bought vegetables from outside to bring home we always need many things to clean it. Take time to clean it and people still worry about vegetable chemical effects [being] not good to my baby and my health. So I spent time on the internet to find out, to discover about safe food and organic. So I thought that organic is the highest safety standard in the world. (Interview, 01/2016)

For both entrepreneurs the concern for their family’s health was said to have been the first reason to turn towards organic agriculture as a source of chemical-free and safe food, with the business idea having followed. In the case of the pregnancy, the general element of responsibility for the health of oneself and one’s family is complemented with another layer of concern: the incorporation of unsafe food would not only harm oneself but also the well-being of the unborn baby.

Not only did the element of responsibility and care prove to be central for organic shopping, it also points towards a related aspect that was described earlier in the gender ratio of shoppers: the responsibility for the bodily integrity of the family’s children through food consumption appears to be a gendered one. In the majority of cases it is not simply parents but specifically mothers or other female relatives who take on the responsibility of ‘safe’ shopping for the health of the children. Females have no less than the responsibility to protect their children’s health through their shopping choices, or as Cairns et al. (2013) in their work on mothering the ‘organic child’ have put it: “the organic child ideal reflects neoliberal expectations about childhood and maternal social and environmental responsibility by emphasizing mothers’ individual responsibility for securing children’s futures” (Cairns et al. 2013, 97). These gendered notions of food work have been addressed elsewhere (see Beardsworth et al. 2002; Cairns et al. 2013; Ehlert, this volume) yet their centrality for organic consumption in Vietnam has not been addressed in prior research. As mentioned, food shopping in Vietnam remains a predominantly female task, yet labour division alone does not reveal how far this gendered responsibility stretches into the realms of family care.

Summarising Remarks: Organic Food Consumption as Individualised Responses to Food Safety Concerns

What the empirical data revealed is the widespread concerns around questions of food, its safety and overall health effects. Growing public discourse on health problems related to food increases pressure on individuals for the micro-management of themselves as well as everyday foodways (Parsons 2015, 80). This notion of responsible individualism reflected in the three empirical sections discussing questions of environmental concern, food safety and health as well as responsibility and care.

Environmental concerns do not appear to be of priority for consumers of organic food in Vietnam. Neither the environmental aspect of organic agriculture nor questions of food miles of imported organic products were raised by the customers. The critique of long transport routes within the corporate-organic foodscape as defeating the purpose of organic agriculture was not a topic of concern. Rather than regarding more abstract and distant concerns for the environment, the empirical data suggests that organic consumption in urban Vietnam is driven by more individualised concerns, namely for the integrity of people’s health.

Health and food safety concerns that were at the core of the interviewees’ motivation for purchasing organic food reflect deep insecurities in the arena of food more broadly. One can say that the topic of food safety in contemporary Vietnam is a contested field with manifold warnings and guidelines on sides of the government, the media as well as private enterprises. Fuelled by constant media coverage and social media debates (see Talk Vietnam 2016; VietNamNet 2016; Viet Nam News 2016), issues of food safety are ingrained into the public’s awareness and result in people worrying for their bodily well-being in a seemingly unsafe environment. It is in this context that organic food consumption becomes an individualised attempt by urban consumers to respond to their food safety concerns by consuming what is perceived to be a safe and healthy food option. By being interlaced with food safety, explicitly organic food can be seen as one component in a wider trend also comprising ‘safe’ and hygienic foods that become increasingly common in Vietnam and more generally in Southeast Asia (Scott et al. 2009, 69).

Safety and health concerns became particularly prominent in relation to certain pivotal moments—either in terms of one’s health or the care and responsibility for children’s well-being. Under these circumstances, people’s individual responsibility to choose harmless and healthy food was further emphasised, again pointing towards notions of the responsible consumer as well as the role of health concerns within organic food consumption. Moreover, responsible individualism and food safety concerns proved to be important drivers for the interviewed entrepreneurs, whose business ideas started from the quest for safe food for themselves and their families that could not be met by the existing food sphere.

Moreover, the interviews revealed certain patterns of trust negotiation, often through the personal element of friends’ recommendations or by trial and error; customers did not blindly trust in organic but often rather relied on their social relations or their senses to assess the food’s qualities. This can be seen in light of the at-times inflationary usage of the term organic within HCMC’s foodscape as well as a mistrust towards food labels in Vietnam more generally that in turn relate back to topics of food safety (see Figuié et al., this volume).

Conclusion: Questions of Responsibilisation and Food Anxiety in Vietnam’s Organic Sector

After zooming in on particularities of organic food consumption in HCMC, the conclusion now zooms out again to put the city’s organic niche into the wider perspective of the discussed trajectories of Vietnam’s organic sector more broadly. Working out the particularities of organic food shopping for urban consumers in HCMC has allowed for illustration of the differences in motivation between customers of the organic niche market in Vietnam and other world regions as well as between respective Vietnamese customers and (foreign) actors of organic initiatives in Vietnam. As discussed, the organic sector in Vietnam emerged under very different circumstances than in countries of the Global North, namely often with foreign (donor-funded) NGO and corporate involvement with respective agendas as well as in a context of a rapidly transforming food system characterised by a range of food safety concerns. As the empirical section has shown, individual motivations of consumers for buying organic generally differ widely from the official rationale of environmental protection behind foreign-financed organic initiatives as well as some of the domestic initiatives. Rather than relating their organic purchases to the environmental benefits of organic farming, customers’ choices of organic food have proven to be deeply intertwined with concerns about the well-being of themselves and/or the ones they feed. This concern with individual health and physical integrity then must be put in the context of the current discourse around food safety in Vietnam and people’s concomitant food anxieties.

With a governmental focus on food productivity, the organic sector leads a niche existence that only recently received increased attention from the state. Latest governmental statements indicate a clear corporate-oriented focus with the target of the organic sector catering to high-income groups within Vietnam as well as affluent export markets. Meanwhile, the political climate of the one-party state towards (environmental) social movements and protests is not exactly favourable, which could be one factor for the organic sector being rather corporate-oriented and accommodating less critical voices and movements towards the corporate-organic foodscape than is the case in some other southeast Asian contexts (Scott et al. 2009).

Within the constellation of the state, the market and individuals that show neoliberal tendencies such as the responsibilisation of the individual alongside a strong socialist state, responsibilities and competencies are not always clear and create ambivalences and insecurities. As has been described for the case of China—which in this regard is not dissimilar from Vietnam—“[t]he breathless pace of market reforms has created a paradox in which the pursuit of private initiatives, private gains, and private lives coexists with political limits on individual expression” (Ong and Zhang 2008, 1). Similarly, agency of individuals in this system predominantly takes place within market logics and less so through civil society, a dynamic that was observable within Vietnam’s organic sector as well. Agency being confined to the realms of the market further speaks to the initial mention of potential inequalities in regard to food. In light of HCMC’s organic sphere—whose spatial concentration in high-income districts was described earlier—the socio-economic and educational background of organic customers seems neither surprising nor incidental. Organic food shopping for individual health and safety reasons is a shape of corporatised agency not available to wide masses of the current population—not only within HCMC but also nationwide with organic being an urban and high-priced phenomenon.Footnote 12

Moreover, this chapter has shown how consumers manoeuvre between domestic food safety and consumer discourses, internationally acquirable information, and global discourses on environmentalism in regard to organic farming that is growing increasingly accessible in globalising Vietnam. The overlapping and at-times contradictory multitude of discourses and questions of responsibilisation constitute a source of anxiety—in terms of food safety but also concerning more general questions of who is in charge and trustworthy in the current food system.

Thus for a range of reasons, the future development of Vietnam’s organic sector will continue to deserve academic attention. Particularly in light of the findings that among urban consumers of organic food, it was often trial and error or personal recommendations rather than an organic label that established trust in organic products, the question of the future of certification within the Vietnamese market arises. Others have already recommended small bottom-up food initiatives due to the importance of social relations, word of mouth advertisement as well as widespread mistrust towards governmental action on issues of sustainability and a certain reluctance to follow governmental regulations (de Koning et al. 2015, 617). Therefore, in the current food system of ambivalences, anxieties and conflicting interests, it remains to be seen what will happen to perceptions of organic food if the state implements the expressed plans of getting further involved in the country’s organic sector.

Notes

- 1.

‘Food system’ here is understood very broadly as a system entailing the production, processing, packaging, distribution, retail and consumption of food (Ingram 2011).

- 2.

GLOBALG.A.P. is a certification scheme and standard for ‘good agricultural practice’ in 80 countries which aims to reduce hazards in production, harvest and handling of produce. In Vietnam the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) has authorised primarily private providers to certify compliance with VietGAP. The criteria of VietGAP are slightly lower than those of GLOBALG.A.P. (Nicetic et al. 2010).

- 3.

An established form of internal certification are Participatory Guarantee Systems (PGS). PGS is an organic quality assurance system through social control, participation and knowledge building rather than through third-party certification. Mostly used within local economies, PGS offers low-cost quality assurance which is often more viable for small-scale farmers than third-party organic certification which poses cost and bureaucratic barriers (IFOAM n.d.).

- 4.

Examples for common governmental organic standards are the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Organic Program, the Japanese Agricultural Standards and the EEC Regulation No. 2092/91 of the European Union (Scott et al. 2009, 76).

- 5.

I am aware that ‘civil society’ is a controversial term in the context of Vietnam, as under an authoritarian regime there is limited space for political expression of civil society or social movements, partly as there are no registered civil society organisations which are completely autonomous from the Vietnamese state (Wells-Dang 2010, 2014). Yet if widening the gaze from legally registered NGOs to including more informal networks, one does find a range of civil society activities (Wells-Dang 2014).

- 6.

If the phenomenon of advertising food as organic which does not adhere to organic standards goes back to a confusion of terminology, or is a problem of free riders, remains to be answered clearly and could be of interest for future research on organic provision in Vietnam.

- 7.

Estimates on the share of certified organically managed agricultural land among Vietnam’s total agricultural land vary. The Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) survey 2008 estimated the share of organic agricultural land in Vietnam to be 0.2 per cent (Willer et al. 2008, 235) whereas the FiBL survey 2017 estimated the organic share to already make up 0.7 per cent (Willer and Lernoud 2017, 315). Others have estimated the share of organic agricultural land as high as 1 per cent (Nguyen Sy Linh 2010, 128). As the available figures are based on certified organic farming only, the overall share of land under organic cultivation might be much higher.

- 8.

All interview partners mentioned in this research were anonymised.

- 9.

The interviews in Vietnamese were conducted with the help of an interpreter and are quoted here in their English translation.

- 10.

According to the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, the average urban per capita income in 2012 was around VND 2.9 million monthly, or almost USD 1700 yearly. Yet due to discrepancies between official and unofficial incomes, medium salaries in Vietnam are challenging to pinpoint and room for potential inaccuracy should be remembered (de Koning et al. 2015, 610).

- 11.

Other survey-style research on the motivations of urban organic consumers in the region at times also came to the conclusion that the environmental friendliness of organic production was part of people’s reason to buy organic, for instance in Bangkok (Roitner-Schobesberger et al. 2008) or Shanghai (Hasimu et al. 2017).

- 12.

Issues of food safety in relation to social inequality in contemporary Vietnam constitute the main focus of the author’s PhD research.

References

APEC, 2008. APEC regional development of organic agriculture in term of APEC food system and market access, APEC#209-AT-01.6.

Barendregt, B.A., Jaffe, R., 2014. The Paradoxes of Eco-Chic. In: Barendregt, B.A., Jaffe, R. (eds.). Green consumption: the global rise of eco-chic., London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 1–16.

Baumgartner, U., Tuan Hoang Nguyen, 2017. Organic certification for shrimp value chains in Ca Mau, Vietnam: a means for improvement or an end in itself? Environment, Development and Sustainability 19, 987–1002.

Beardsworth, A., Bryman, A., Keil, T., Goode, J., Haslam, C., Lancashire, E., 2002. Women, men and food: the significance of gender for nutritional attitudes and choices. British Food Journal 104, 470–491.

Bitter-Suermann, M., 2014. Food, modernity, and identity in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Dissertation, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Biz Hub, 2016. Fruit producer Vinamit get US, EU organic certification [WWW Document]. Việt Nam News. URL http://bizhub.vn/news/fruit-producer-vinamit-get-us-eu-organic-certification_282833.html (accessed 02.25.18).

Boström, M., Klintman, M., 2006. State-centered versus Nonstate-driven Organic Food Standardization: A Comparison of the US and Sweden. Agriculture and Human Values 23, 163–180.

Bricas, N., 1993. Les caractéristiques et l’évolution de la consommation alimentaire dans les villes africaines. In: Muchnik, J. (ed.). Alimentation, techniques et innovations dans les régions tropicales. Paris: L’Harmattan, 127–160.

Brown, E., Dury, S., Holdsworth, M., 2009. Motivations of consumers that use local, organic fruit and vegetable box schemes in Central England and Southern France. Appetite 53, 183–188.

Brunner, J., 2014. Organic shrimp certification: A new approach to PES. VNFF Newsletter No 2 Quarter II/2014. Vietnam Forest Protection and Development Fund, Hanoi, 7–11.

Cairns, K., Johnston, J., MacKendrick, N., 2013. Feeding the ‘organic child’: Mothering through ethical consumption. Journal of Consumer Culture 13, 97–118.

Carvalho, F.P., 2006. Agriculture, pesticides, food security and food safety. Environmental Science & Policy 9, 685–692.

Conway, G.R., Barbier, E., 1990. After the green revolution: sustainable agriculture for development. London; New York: Earthscan Publications.

de Koning, J.I.J.C., Crul, M.R.M., Wever, R., Brezet, J.C., 2015. Sustainable consumption in Vietnam: an explorative study among the urban middle class. International Journal of Consumer Studies 39, 608–618.

Ehlert, J., 2016. Emerging consumerism and eating out in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The social embeddedness of food sharing. In: Sahakian, M., Saloma, C.A., Erkman, S. (eds.), 2016. Food consumption in the city: practices and patterns in urban Asia and the Pacific, Routledge studies in food, society and the environment. London; New York: Routledge, 71–89.

Figuié, M., Bricas, N., 2010. Purchasing Food in modern Vietnam. In: Kalekin-Fishman, D., Low, K.E.Y. (eds.), Asian Experiences in Every Day Life: Social Perspectives on the Senses. Burlington: Ashgate, 177–194.

Figuié, M., Moustier, P., 2009. Market appeal in an emerging economy: Supermarkets and poor consumers in Vietnam. Food Policy 34, 210–217.

Fortier, F., Tran Thi Thu Trang, 2013. Agricultural Modernization and Climate Change in Vietnam’s Post-Socialist Transition: Agricultural Modernization and Climate Change. Development and Change 44, 81–99.

Gainsborough, M., 2010. Present but not Powerful: Neoliberalism, the State, and Development in Vietnam. Globalizations 7(4), 475–488.

Goodman, D., Goodman, M., 2001. Sustaining Foods: Organic Consumption and the Socio-Ecological Imaginary. In: Cohen, M.J., Murphy, J. (eds.), Exploring Sustainable Consumption. Oxford: Elsevier Science, 97–119.

Grosglik, R., 2016. Citizen-consumer revisited: The cultural meanings of organic food consumption in Israel. Journal of Consumer Culture 17, 732–751.

Guthman, J., 2004. Back to the Land: The Paradox of Organic Food Standards. Environment and Planning A 36(3), 511–528.

Hasimu, H., Marchesini, S., Canavari, M., 2017. A concept mapping study on organic food consumers in Shanghai, China. Appetite 108, 191–202.

Hassanein, N., 2003. Practicing food democracy: a pragmatic politics of transformation. Journal of Rural Studies 19, 77–86.

Heis, A., 2015. The alternative agriculture network Isan and its struggle for food sovereignty – a food regime perspective of agricultural relations of production in Northeast Thailand. ASEAS – Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies 8(1), 67–86.

Ho Thi Diep Quynh Chau, 2015. CÁC YẾU TỐ ẢNH HƯỞNG ĐẾN Ý ĐỊNH MUA THỰC PHẨM HỮU CƠ CỦA NGƯỜI TIÊU DÙNG TẠI TP.HCM., Master Thesis, Ho Chi Minh City Open University.

IFOAM, 2003. Developing Local Marketing Initiatives For Organic Products In Asia, A Guide for Small & Medium Enterprises. IFOAM, Germany, 2003.

IFOAM, 2005. The Principles of Organic Agriculture. Preamble. IFOAM, Bonn, available under https://www.ifoam.bio/sites/default/files/poa_english_web.pdf (accessed 02.22.17).

IFOAM, n.d. PGS General questions [WWW Document]. URL https://www.ifoam.bio/en/pgs-general-questions (accessed 02.20.18).

Ingram, J., 2011. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Security 3, 417–431.

Johnston, J., Biro, A., MacKendrick, N., 2009. Lost in the Supermarket: The Corporate-Organic Foodscape and the Struggle for Food Democracy. Antipode 41, 509–532.

Little, R., Maye, D., Ilbery, B., 2010. Collective Purchase: Moving Local and Organic Foods beyond the Niche Market. Environment and Planning A 42, 1797–1813.

MacKendrick, N., 2014. Foodscape [WWW Document]. contexts. understanding people in their social worlds. URL https://contexts.org/articles/foodscape/ (accessed 02.23.17).

MARD, 2017. Prime Minister approves agricultural restructuring plan in 2017–2020 [WWW Document]. Cổng thông tin điện tử Bộ NN và PTNT. URL https://www.mard.gov.vn/en/Pages/prime-minister-approves-agricultural-restructuring-plan-in-2017-2020.aspx (accessed 02.21.18).

Mergenthaler, M., Weinberger, K., Qaim, M., 2009a. Consumer Valuation of Food Quality and Food Safety Attributes in Vietnam. Review of Agricultural Economics 31, 266–283.

Mergenthaler, M., Weinberger, K., Qaim, M., 2009b. The food system transformation in developing countries: A disaggregate demand analysis for fruits and vegetables in Vietnam. Food Policy 34, 426–436.

Moustier, P., Figuié, M., Nguyen Thi Tan Loc, Ho Thanh Son, 2006. The role of coordination in the safe and organic vegetable chains supplying Hanoi. In: I International Symposium on Improving the Performance of Supply Chains in the Transitional Economies 699, 297–306.

Moustier, P., Phan Thi Giac Tam, Dao The Anh, Vu Trong Binh, Nguyen Thi Tan Loc, 2010. The role of farmer organizations in supplying supermarkets with quality food in Vietnam. Food Policy 35(1), 69–78.

Ngo Doan Dam, n.d. Production and supply chain management of organic food in Vietnam, Field Crops Research Institute (FCRI), Vietnam Academy of Agricultural Sciences (VAAS), 1–6.

Nguyen Sy Linh, 2010. Viet Nam: Organic Development. In: Willer, H., Kilcher, L., (eds.), 2010. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2010. IFOAM, Bonn and FiBL, Frick, 128–130.

Nguyen Thi Hoan, Mergenthaler, M., 2005. Food safety and development: how effective are regulations. In: Proceedings of Deutscher Tropentag, 11–13.

Nguyen-vo Thu-huong, 2008. The ironies of freedom: sex, culture, and neoliberal governance in Vietnam, Critical dialogues in Southeast Asian studies. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Nicetic, O., van de Fliert, E., Ho Van Chien, Vo Mai, Le Cuong, 2010. Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) as a vehicle for transformation to sustainable citrus production in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. 9th European IFSA Symposium, 4–7 July 2010, Vienna, Austria. WS 4.4 – Transition towards sustainable agriculture: from farmers to agro-food systems, 1893–1901.

Oliveri, F., 2015. A Network of Resistances against a Multiple Crisis. SOS Rosarno and the Experimentation of Socio-Economic Alternative Models.

Omoto, R., 2012. Small-scale producers and the governance of certified organic seafood production in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta. Dissertation, University of Waterloo.

Ong, A., Zhang, L., 2008. Introduction: Privatizing China. Powers of the Self, Socialism from Afar. In: Li Zhang, Aihwa Ong, (eds.), 2008. Privatizing China: socialism from afar. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Parayil, G., 2003. Mapping technological trajectories of the Green Revolution and the Gene Revolution from modernization to globalization. Research Policy 32, 971–990.

Parsons, J.M., 2015. Gender, class and food: families, bodies and health. London; New York: Palgrave Macmillan (Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Family and Intimate Life).

PGS IFOAM, n.d. Participatory Guarantee Systems Worldwide [WWW Document]. URL https://pgs.ifoam.bio/ (accessed 02.20.18).

Pham Binh Quyen, Dang Duc Nhan, Nguyen Van San, 1995. Environmental pollution in Vietnam: analytical estimation and environmental priorities. TrAC – Trends in Analytical Chemistry 14, 383–388.