Abstract

This chapter introduces the project that aimed at mapping the institutional landscape changes in higher education in 15 post-Soviet countries. The project takes the Soviet legacy as a point of departure and describes and analyses the important developments that took place with the fall of the Soviet system and the impacts these developments had on the landscape. Key developments pertain to, for example, the change from a state-dominated ideology to a steering philosophy with many market elements, finding a new balance between supply and demand, international developments and demographic developments. The landscapes have changed significantly with the emergence of non-state providers, a reconfiguration of “traditional” institutions (universities, academies, institutes) and also a growth in the public sectors of higher education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1991, the Soviet model of higher education in 15 republics of the USSR, with its 5.1 million students and 946 higher education institutions, started 15 independent journeys. All post-Soviet systems shared the legacies of the single Soviet approach to higher education provision: a centrally planned organization and financing, subordination to multiple sectoral ministries, a national curriculum, a vocational orientation based on the combination of strong basic education and narrow specialized job-related training, a nomenclature of types of higher education institutions, tuition-free study places and guaranteed employment upon graduation combined with mandatory job placement. Despite these commonalities, the sociocultural and economic disparities across the republics were remarkable: for example, in the structure of the economy, the level of urbanization, the cultural and ethnic diversity and demographic trends, as well as the number of higher education institutions, the number of students and higher education participation rates.

After gaining their independence, all new countries faced similar challenges. First of all, there were the challenges of the consolidation of the new nation and the introduction of a market economy. Second, the collapse of the centrally planned economy was associated with economic decline, political instability, a drastic drop in public funding and brain drain from higher education and research institutions to other sectors of the economy or overseas. Many post-Soviet countries—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan and recently Ukraine—experienced armed conflicts, which deeply affected their societies and economies. The similarities and differences between the national contexts, together with the challenges of the independence period, created a unique constellation of political, economic, sociocultural and demographic conditions in each country.

In higher education, almost all the new nations adopted a similar package of reforms, many of these neo-liberal in nature (Silova and Steiner-Khamsi 2008; Smolentseva 2012) that aimed to “normalize” their higher education systems. This would be achieved through the establishment of a non-state sector, the introduction of tuition fees in the public sector, national standardized tests for admission exams to higher education, decentralization of the governance and—although not in all countries—loans for students and performance-based funding. The argument in favour of this particular set of reforms was socially constructed (Fourcade-Gourinchas and Babb 2002), in terms of the perceived need to follow a certain ideal type. Reform was presented as following the ideal type of the single model of excellence in higher education (Heyneman 2010), or catching up, not lagging behind other countries (Silova and Steiner-Khamsi 2008) in the context of an increasing interest in and greater opportunities to attend higher education. The main features of the ideal type of higher education were taken from the Western world. The implementation of the reforms varied in speed and timing across countries. Some countries were not so much affected in the early years of independence (in particular, Turkmenistan), but in recent years that country too has become more responsive to international policy trends.

Other important reforms across the region included efforts to overcome Soviet ideological legacies and align higher education systems with the goals of new nation building. Thus, Soviet ideological courses were excluded from curricula. Along with the change of the official language in all countries, titular nation language became predominant in higher education instruction, and the higher education programmes were supplemented by courses on national history and culture.

All of these transformations have dramatically affected individuals, social groups and institutions of post-Soviet societies, including higher education. All have had to adapt to their rapidly changing environments. That has eventually resulted in a range of changes in the structure of national higher education systems and in—what we term—their institutional landscapes, the overall institutional composition of the higher education system.

Despite the scale and importance of the changes that have taken place, there are only few comparative studies of post-Soviet higher education transformation. In many countries, the weakness of the social sciences due to a lack of research funding, together with the long-standing isolation from international research communities, partly explains that absence. Interestingly, comparative research with a focus on secondary education in post-Soviet systems seems more prolific than research on higher education (e.g. Phillips and Kaser 1992; Silova 2010a). There are publications which aim to analyse several countries of the region and/or the nature of post-Soviet transformations (see Heyneman 2010; Johnson 2008; Silova 2009, 2010a; Silova and Steiner-Khamsi 2008). There appear to be no comparative higher education studies on the region based on primary data collection and analysis, as distinct from studies consisting of reviews of literature and policy documents (but see Silova 2010b; Slantcheva and Levy 2007).

This book is the outcome of the first ever study of the transformations of the higher education institutional landscape in 15 former USSR countries following the disintegration of the Soviet Union (1991). It explores how the single Soviet model that developed across the vast and diverse territory of the Soviet Union over several decades changed into 15 unique national systems, systems that have responded to national and global developments while still bearing significant traces of the past. This study is distinctive in that (a) it presents a comprehensive analysis of the higher education reforms and transformations in the region in the last 25 years; (b) it focuses on institutional landscape through the evolution of the institutional types established and developed in pre-Soviet, Soviet and post-Soviet times; (c) it embraces all 15 countries of the former USSR; and (d) it provides a comparative analysis of the drivers of transformations of institutional landscape across post-Soviet systems.

The institutional landscape of higher education is one of the key characteristics of higher education systems. Approaching higher education transformations through the lens of changes in the institutional landscape enables several goals to be achieved. First, it makes it possible to incorporate the dynamic dimension, to trace the processes of change. Second, it includes an analysis of the drivers of change, which opens up the opportunity for systematic analysis of higher education system transformations and the factors behind them, including governmental policies, institutional behaviour, demographic change, global forces and others. Third, it allows the researcher to look at system level while keeping in mind the diversity of the institutions.

Despite an increasing interest in studying institutional landscapes and institutional diversity in higher education around the world (Huisman 1998; Huisman et al. 2007; van Vught 2009), very little research has been focused on the institutional landscape in post-Soviet systems, despite the major transformations in those landscapes (for Russia, see Knyazev and Drantusova 2014; Froumin et al. 2014).

In the remainder of this chapter we present a conceptual framework which guided the project. Following a short introduction to the Soviet model and an overview of the reforms that took place across the 15 systems, the chapter focuses on the project findings—the changes in the institutional landscape, its drivers and a brief reflection on what the future may bring. This chapter also introduces all country cases included in the study and highlights their main points, after which it concludes with our final reflections on the changes in higher education institutional landscapes in 15 post-Soviet countries.

The Conceptual Approach and Research Design

The concept of the institutional landscape covers two aspects. First, it denotes the idea of institutional (or organizational) diversity. Higher education systems consist of a variety of institutions. These institutions may differ in various respects. Birnbaum (1983) distinguished various dimensions of diversity, and many of these will also figure in our description and analysis of the post-Soviet systems. Particularly, three dimensions are key to our project: systemic diversity, differences in size, type and control within a higher education system; structural diversity, differences in historical and legal foundations; and programme diversity, differences in degree level, area, mission and emphasis of programmes within the institutions.

The second aspect of the landscape signifies how the different dimensions of diversity play out in a particular system. That is, various stakeholders classify higher education institutions on the basis of the various diversity dimensions. Governments are key players by, for example, labelling certain higher education institutions as polytechnics or universities of applied sciences or—as we will see in the subsequent chapters—as academies, institutes and (research) universities. Whereas governments are key, there are other actors that may figure, for instance, representatives of certain types of institutions (e.g. the Russell Group in the UK, the Group of Eight in Australia).

Two concepts are helpful to make more sense of this second aspect: vertical and horizontal differentiation (Teichler 1988). Horizontal differentiation refers to making distinctions between types of higher education institutions on the basis of their function within the broader fabric. Such differentiation likely reflects the needs and demands of different groups in society, including the government (see also Taylor et al. 2008). As such, the landscape or configuration could be seen as a reflection of a social pact (Gornitzka 2007). Following this logic, it makes sense to distinguish, for example, hogescholen from universities in the Netherlands, because they fulfil different roles, professional education versus academic education, and applied research versus basic research, respectively. That such distinctions are not watertight (as the demise of the binary systems in, e.g. the UK and Australia shows) is beyond the point: there is (or has been) a functional reason to label higher education institutions differently.

Vertical differentiation refers to differences in status and prestige, with further connotations like “elite” and “high quality”. Such differences are less tangible and likely more dynamic than horizontal differences. This is because status and prestige are in the eye of the beholder and therefore malleable. Across the globe, the globally oriented comprehensive research university (sometimes called the world-class university) is quite often seen as the type of institution at the top of the status hierarchy. The underlying dynamics are quite different from horizontal differentiation and sometimes at odds. Through processes of academic drift those institutions lower in the pecking order may emulate higher-status institutions and this could undermine the functional differentiation. Obviously, academic drift is not the sole driver of changes in the landscape. On the basis of our understanding of the literature (e.g. Teichler 1988; Huisman 1998), there are various factors that would affect the institutional configuration: the government’s steering approach, the level of marketization, demographic developments, internationalization and so on.

With these conceptual tools in mind, we asked our country authors to reflect on the following questions: How did the landscape look like at the moment of (or just before) independence? Which developments took place in the system since independence and which drivers can be discerned that impacted the landscape? And, finally, how do the new landscapes look like (and are they much different from those in place around 1990)? We asked authors to rely on available classifications and statistics to arrive at landscape descriptions that would do justice to the state of the art in their systems.

Assuming distinctive features of each national context, the project benefits from the unique institutional classifications developed for each chapter by their authors. The institutional types and classifications established in the late Soviet time serve as a starting point for the analysis of the transformations of the independence period. The post-Soviet classifications embracing state of art of each national system enable to catch the nature of the current institutional landscape and to trace the transformations of the institutional landscape since gaining the independence.

The institutional classifications are developed using a wide range of national- and institutional-level data: affiliation, number of HEIs/students within types, distribution over the country, size, age of the institutions, disciplinary composition, student body characteristics, faculty characteristics, research activity (grants, R&D revenues, publication activity), international activity (international students, faculty, programmes), interrelations with business/production (funding, grants, agreements) and interrelations with other HEIs (net of branches, agreements, mergers).

In their overall analysis, most authors relied on analyses of policy developments in higher education and hence made significant use of policy papers and existing secondary literature. Some authors supplemented these methods with interviews. Some authors analysed higher education landscape using institutional-level data.

The Point of Departure: Soviet Higher Education System

The USSR was a unique combination of peoples and cultures stretching from the Eastern Europe to the Siberian Far East, from Northern Russia to the Caucasus and Central Asia. Over 70 years (for the Baltic republics and Moldova which became a part of the USSR later it was about 50 years) the Soviet system evolved according to common principles that aimed at the building of a new political, socioeconomic and cultural system, that of communism. The sociocultural project of the USSR—the construction of the new Soviet man—became interwoven with the pragmatic purpose of accelerated economic development, in order to overcome the devastating consequences of the two world wars and outpace the capitalist countries in military excellence. The Soviet higher education system was an important player in both of these arenas: as an instrument of the formation of a new type of man and as an instrument of economic progress (Smolentseva 2016).

The Soviet system of higher education had a number of distinctive characteristics. First of all, as is well known, it was characterized as mainly state-centred, with central planning and a top-down command method of administration (Froumin et al. 2014; Kuraev 2016). The higher education system was built into a larger economic planning system and had to respond to orders from higher authorities. Higher education institutions were required to train a specified number of people in certain fields, while the larger economic planning system was responsible for graduates’ job assignments. The control and supervision of higher education institutions were distributed among a large number of sectoral ministries that were responsible for administering specific industries. This structure was created in the Stalin era. From 1929 to 1930 onwards, most higher education institutions were transferred from the ministry of education (Narkompros) to various sectoral ministries and state departments (David-Fox 2012; Ryzhkovskiy 2012). That type of organization was considered to be a more effective way of linking the training of higher educated cadre with the needs of industrialization and military mobilization.

Second, as higher education was a system of training professional, “highly qualified” cadre for the national economy (Kuraev 2015; Smolentseva 2016), it was in many ways predominantly vocational. The need to bring higher education and research closer to “life” and the requirements of the national economy was much discussed during the Soviet years. This affected organization and curricula in higher education. The turn towards a technical and vocational orientation started in the early Soviet period (David-Fox 2012; Ryzhkovskiy 2012) and was maintained over the succeeding decades.

Third, uniformity, the application of the same principles and requirements to all institutions and individuals, was another key feature of the Soviet system (Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1990; Kuraev 2015). This approach contributed to the consolidation of the diverse country in social and cultural terms, including the creation of a “common educational space” via the introduction of the Russian as a common language and the use of standard curricula and textbooks.

The Soviet programme of continuous expansion of the educational system across all republics had results. Each Soviet republic had at least one comprehensive university and a number of specialized higher education institutions. The number of students increased from 811 thousand in 1940 to 5.2 million in 1991. Trends in the number of institutions are less straightforward, due to the ongoing process of opening up, closing down, merging and disintegrating particular higher learning establishments. There were 817 HEIs in 1940, 739 in 1960, 805 in 1970 and 883 in 1980 (see Table A.5 in Appendix). Even in the last decade of the USSR the government kept establishing new HEIs.

Despite the application of similar principles to organization and administration, uneven socioeconomic conditions of the republics were a historical legacy which the Soviet government had to grapple with from its beginning, but did not overcome. There was a special effort to build higher education institutions outside the European part of the country where they were mostly concentrated (Matthews 1982; Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1990). However, one official Soviet indicator, competition for HE admissions per 100 places, suggests that in many republics the interest of the population in higher education was much higher than the system could meet (Table A.16 in Appendix). Higher education systems in the Baltic republics experienced the least pressure, with 154–164 applications per 100 vacancies in 1988. The competition in Central Asia was on average much fiercer, with 291–328 applications per 100 vacancies (but 226 in Kazakhstan). In Georgia the indicator was even higher at 394.

Free higher education (except in the period 1940–1956) and the continuing expansion of higher education were important achievements of the USSR. Many of the barriers to higher education were removed. Social groups previously underrepresented in higher education received increasing opportunities: workers, peasants, women and members of various nationalities. Women comprised 52 per cent of students by the end of the Soviet era, with the lowest gender ratios in Azerbaijan (33 per cent) and Turkmenistan (36 per cent).

The participation rate in higher education, calculated as a gross enrolment ratio (the number of students as compared to the number of people in the 20–24 age cohort), was relatively high in the USSR in general at about a quarter of the age group, but again, it varied significantly across the Republics (Table A.15 in Appendix). The European part of the country had the higher participation with the Central Asian republics and Azerbaijan demonstrating relatively modest indicators (12 per cent for Turkmenistan, 15 per cent for Tajikistan, 16 per cent Kirgizia (Kyrgyz Republic), 15 per cent for Azerbaijan). Using Trow’s division of three stages of massification process (Trow 1973), some Republics had reached the mass stage (15–50 per cent), while in others participation in higher education was still in the elite stage of development (less than 15 per cent).

Another prominent characteristic of the Soviet system was the institutional separation of higher education from research (Johnson 2008; Froumin et al. 2014). From the early Soviet period onwards this structural division played an important role in weakening the Soviet higher education sector. Most research was conducted in sectoral institutes that were directly linked to particular industries and subordinated to the corresponding ministries, as were most of the higher education institutions. The need to connect higher education and research, basic and applied, was constantly discussed in Soviet policy documents (Smolentseva 2016), but the dominant role of higher education remained the same, that of teaching highly qualified manpower (Kuraev 2015). The higher education sector’s share of research was small. For example, in Russia in 1990 it comprised just 6 per cent of all research, while the great bulk of which took place in academies, sectoral institutes and industries (Nauka Rossii v tsifrakh 1994, 41Footnote 1).

The Soviet higher education landscape consisted of universities (comprehensive HEIs) and specialized institutions—institutes, academies, factory-HEIs (zavod-VTUZ) and others. The comprehensive universities comprised a small minority of HEIs (8 per cent) and enrolled 12 per cent of all students by the end of the Soviet era (see Appendix). These universities had two tasks: the reproduction of research and teaching staff in certain fields “humanities, natural sciences, psychology and political economy” (Yagodin 1990) and training for “practical work in national economy, schools and technic, cultural institutions, government departments and corporate bodies (such as trade unions, the Party, etc.)” (Severtsev 1976). The comprehensive universities were supposed to play an important role in research, and their graduates were expected to make use of their research-oriented education in their professional activities.

However, this group of universities was not homogenous. A small number of them had their origins in the imperial period, while the majority was established in the Soviet period, with some of them being upgraded from pedagogical institutes (and keeping the characteristics of those institutes, according to Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1990). In the case of Russia, the biggest higher education system among Soviet republics, including 69 universities in 1988, only 17 out of 37 universities subject to statistical analysis were regarded as well positioned as universities, characterized by well-qualified academic staff, a traditional profile of university fields or a strong research orientation (Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1988). Indeed, despite the official approach of uniformity, a vertically differentiated system of higher education was evident in the USSR.

As noted, the majority of higher learning was organized in specialized institutions for particular jobs: engineers of various kinds, doctors, teachers, economists, lawyers and so on. Engineering students enrolled in HEIs servicing industry, construction, transportation and communication comprised 43 per cent of the total student population (see Table A.6 in Appendix). That group of HEIs comprised almost one third of all HE establishments in the country. Another big group, also about one third of HEIs, were the pedagogical institutions, with 19 per cent of total number of students. The engineering and technical fields dominated in the official list of specialties: 243 out of 381 (64 %) in the ministry list as of 1975 (Ministry of Higher and Secondary Vocational Education 1975) and 177 out 289 (61 %) in 1987 (Ministry of Higher and Secondary Vocational Education 1987). Admissions in philosophy were available in 13 HEIs, in psychology in 12 HEIs and in sociology in only 11 institutions (Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1990).

In the Soviet period, the pre-Soviet orientation towards engineering and technical fields was continued and deepened. “Industrialization” was evident in many universities (Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1988). In this work we set aside the larger question of the nature of the Soviet university, whose characteristics were very different from the traditional notion of the European university (for this topic see Kuraev 2015). Nevertheless, as early as in the Soviet period it was noted that the two distinct higher education sectors, universities and specialized institutes, were developing in converging ways: university education was moving towards more specialized instruction with the inclusion of applied sciences, while specialized educational institutions tend to embrace more academic research in their foundations, becoming more like universities, and paid more attention to research. The “modern technical university” was an example of such converging trends (e.g. the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Moscow Institute of Electronic Engineering, Moscow and Kharkov Institutes of Radio Engineering, Electronics and Automatics and others (Severtsev 1976)). The drift to greater vocationalism within the university sector was fairly common (see Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1988, 1990), but the intensification of research activities within the specialized sector mostly developed within a small group of elite engineering institutions.

By the time of perestroika in the mid-1980s, many issues in the Soviet system of higher education had become evident and were explicitly discussed (Ovsyannikov and Iudin 1990; Smolentseva 2016), and the first movements towards changing the educational system had started. The legalization of cooperatives (1988) as a Soviet form of entrepreneurship opened an opportunity to create alternative educational provision. For example, in Estonia by 1989 two non-state higher education institutions were already established (see the chapter on Estonia in this volume). That period also introduced the term “customer” into the public policy domain (Smolentseva 2016), where the production sector served in this role, being called upon to evaluate the quality of training of specialists. The differentiation of the large higher education system was already noted. It was acknowledged that there were genuine education and research centres but also many without quality in either theoretical or practical training.

The 25 Years of Changes: Higher Education Reforms and Contexts

After the disintegration of the USSR, the new independent nations were looking for quick solutions to stabilize and develop their economies. Some declared themselves as “normal” Western market-based democracies; some adhered to more conservative and isolationistic approaches. In all countries, the economic collapse, transformational recessions, the breakdown of economic ties with the other former republics in what was a large federal network and political changes had dramatic effects on the economy and living standards. Measures that introduced market mechanisms into the ruined centrally planned economies were supposed to revive the economic development.

In his comparative analysis of the transitional economies of Central and Eastern Europe, the Baltics, and 12 CIS countries, Izyumov (2010) finds that in all CIS countries the reforms were implemented by inconsistent shock therapy, ineffective privatization and highly inflationary monetary policies. Public participation in the reform agenda was narrow, which prevented those countries from developing policies that would reduce the negative effects of reform for the population. The transition to a market economy had a high human cost, especially in the countries of the former USSR. Despite the different political regimes that emerged within the former USSR, ranging from more democratic to autocratic, the drastic decline in the standards of living was evident in all countries. In the first 5–10 years of reforms, GDP and GDP per capita dropped dramatically, while the Gini coefficient increased (again, with some variations: e.g. for poor countries like Uzbekistan that change in indicators was not significant). In the absence of supportive governmental policies, private initiatives to cope with transformation often took destructive forms, boosting the informal economy, corruption, crime and drugs use (Izyumov 2010). Neo-liberal ideology, which asserted a limited role of the state and individuals’ responsibility for their own well-being, was timely in the countries trying to overcome the legacies of the overwhelming state/central control.

Against this dramatic backdrop, liberalization also took place in higher education. The opening up of the educational system, like the entire society, had started in the perestroika period. At the beginning of the period of independence, it was expected that private property, market mechanisms and the absence of state and party control would help to overcome the problems of socialist education (in some countries, including corruption at admissions—see chapter on Azerbaijan, for instance). It was hoped that a change from total state control to autonomy, from uniformity to diversity, from the engineering and vocational bias towards greater humanitarization and personal development would have a crucial impact on the political, economic, social and cultural progress of the society. Education was seen as a key to the new society, and eliminating the state monopoly in education was often seen as an instrument of the expected positive development.

Marketization

Accordingly, the earliest reforms in most of the countries of the region were the introduction of a non-state/private sector in higher education and tuition fees in the public sector for both full-time and part-time programmes. The latter was not something that all transitional countries of Central and Eastern Europe did. They either kept their higher education public (e.g. Slovak Republic) or charged fees only for part-time programmes (e.g. in Poland). In all post-Soviet countries, including the Baltics and except for Turkmenistan which only introduced fees recently in a few higher education institutions (HEIs), the impoverishment of the public sector economy inevitably led HEIs to seek for funding elsewhere. Taking tuition fees from the population was essential to the survival of higher education. Tuition fees not only directly brought money into the public HEIs, they also supported largely the same faculty from public HEIs when they took supplemental teaching jobs at non-state HEIs.

As the comparative data show (see Table A.19 in Appendix), in the first ten years after independence, the non-state institutions in many countries of the region have grown very fast, and in five countries (Armenia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Moldova) exceeded the number of public institutions. Two countries (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan) do not have non-state providers of higher education. Tajikistan closed down most non-state providers, except for one.

However, as case studies in this book will also show, the non-state sector in an absolute majority of the countries was unable to gain the same level of prestige and demand for attendance as the traditional public sector. In the absolute majority of countries, the enrolments continued to be concentrated in the public institutions (Table A.20 in Appendix).

Perhaps the only deviation from this trend is visible in Kazakhstan, where the course of neo-liberal reforms was more explicit than in other countries of the region. In 2015, 52 per cent of students in Kazakhstan enrolled in non-state institutions (Table A.20 in Appendix). Kazakhstan went further in privatization by not only shifting the costs of higher education to the families of students enrolled but also by changing the legal status of several Soviet institutions of higher education into joint stock companies (see the chapter on Kazakhstan).

Therefore, the more striking change took probably not place through the creation of non-state/private sectors but through the transformation of public sectors, which largely changed their economic basis to private funding. In public HEIs in most of the countries, except for Estonia and Turkmenistan, more than half of all students pay fees. Fee payers comprise up to 85 per cent in the Kyrgyz Republic. The share of student population of the region that pays fees to either state or non-state providers further illustrates this point, demonstrating the big change from the full public provision to the privatization of costs of higher education in the region.

Marketization of higher education had another important implication for most of the higher education systems of the region: students and their families became an important source of revenues, and higher education became more consumer-oriented. It led to a rapid expansion of enrolments in the fields of business studies, economics, foreign language studies and law. The public sector immediately started to offer degrees in those fields (either with or without tuition fees). The non-state/private sector was also mostly built around these fields, as these types of programmes were cheaper to provide and had a high demand. As our case studies show, the change from predominantly engineering education to the domination of “soft” fields had significantly changed the higher education landscape. A “consumerist turn” (Naidoo et al. 2011) has taken place in this part of the world too.

Following Kwiek, who reflects on the particular path of marketization in Poland (2008, 2011), we argue that in the case of post-Soviet states, marketization of higher education was dual: both internal to the public sector (through tuition fees) and external (through the emergence of non-state providers). We also argue that unlike in Poland, where internal privatization was limited to the part-time programme domain, “creeping marketization” in the post-Soviet states was much more severe, as the level of penetration of quasi-market forces through user fees was implemented at a larger scale. Public higher education institutions could “sell” the most prestigious “commodity”: a full-time degree in highly desirable fields stamped by established HEI “brands”, hardly limited by governmental regulations, especially in the first years of independence.

The privatization of costs opened the way to a remarkable expansion in higher education. In most countries, higher education enrolments at least doubled by the mid-late 2000s: in Belarus, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan and Ukraine. Significant growth also took place in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. In just two countries, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, enrolment numbers declined. In Turkmenistan, the absolute enrolment decreased twice at the beginning of the reforms and is still far behind the situation in the Soviet period (currently about 20,000 students compared to 40,000 in the Soviet period). In Uzbekistan, the enrolment also decreased sharply at first and the system has yet to achieve the Soviet level of student numbers (about 260,000 now versus over 300,000 in the Soviet era) (see Tables A.22 and A.24 in Appendix; for massification, see, e.g. Smolentseva 2012; Platonova 2016).

In this way countries that already achieved Trow’s mass stage of higher education by the end of the Soviet era moved towards and beyond Trow’s threshold of 50 per cent for ‘universal’ higher education. As such, attending higher education more or less became the social norm, especially in the countries of the European part of the region—the three Baltics states, Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. However, by the mid-late 2000s those systems faced the demographic decline due to the low birth rates of the turbulent 1990s. This resulted in decreasing enrolments in non-state and public sectors. Overall, the demographic change has led to system contraction: in Belarus, the Baltics, Russia and Ukraine (also Moldova, but by participation rate this country is in another group). De-privatization (an increasing role of public funding in contrast to the previous trend to privatization) has become a new trend in the region (Kwiek 2014), which dramatically affects all dimensions of national landscapes of higher education (see respective country chapters).

The two Central Asian countries, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, have demonstrated quite the opposite case. They have seen a unique process of de-massification, accompanied by tight government control over higher education and a pattern of demographic growth. The access bottleneck created in the Soviet time (e.g. see the above indicators on competition per 100 places and the chapter on Uzbekistan) has built up more pressure in the independence period, and that contradiction has not yet been resolved.

The other countries—Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan—have experienced various fluctuations over the independence period, but all of them have tended to remain in the mass phase of the massification process. In most of them there has been a recent decline in participation because of governmental policy, including quality assurance mechanisms (including programme and institutional accreditation), in combination with demographic trends. In this group of countries, except for European Moldova, the demographics are rising. This creates additional pressure on the educational system.

Admissions Reform: Introduction of National Standardized Tests

One of the key transformations of higher education systems in the region was the reform of admission system. In the Soviet period, each HEI held written and oral examination in subjects corresponding to the field of study. Examinations took place in person, at the same time in all HEIs, with a couple of exceptions. For instance, Moscow State University conducted admissions earlier than the majority of the other institutions. An applicant could take exams only at one institution at a time. Failing the exams meant one had to wait for another year to try again. The Soviet admission system was widely criticized as restricting equity (talented students could not travel to other cities to take exams) and enabling corruption (lacking transparency).

Standardized tests have been introduced in all post-Soviet countries, except for Turkmenistan. Even in Uzbekistan the national test was introduced quite early—in 1994, unlike, for example, Russia, where it became a prevailing form of admissions only in mid-late 2000s or Tajikistan (in 2014). The subject tests enable candidates to apply to a higher education programme and—if scores would be sufficiently high—to be eligible for a tuition-free place (in some countries, it is called “grants”). The test was considered as an instrument to overcome shortages in the Soviet system and ensure quality and transparency of admissions, decrease corruption and enhance educational equity. It was a significant change of the traditional system and its introduction was accompanied with lots of discussions and tensions. Assessments of the outcomes of these reforms were ambiguous. In some countries the new test system addressed the corruption issue (see chapter on Georgia) or failed to ensure transparency (see chapter on Uzbekistan). In some countries it probably increased social mobility somewhat, but also fostered inequities by advantaging those from better-off families (see chapters on Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic). In addition, the new admission system has become a market mechanism introducing competition among HEIs for “better prepared” students, and thus more public funding, as in most countries academic merit is linked to governmental support. That indeed has led to an increasing vertical institutional differentiation within higher education systems. In many countries the average score of the national university entrance test became one of the key indicators of the prestige and status of a university (see chapters on Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Russia).

Bologna Reforms

Most of the countries of the region joined the Bologna process, starting with the three Baltic states (1999), Russia (2003), then Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine (2005), Kazakhstan (2010) and Belarus (2015). Kyrgyz Republic applied, but was turned down. Only four countries, all in Central Asia (Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan), are outside of the Bologna group.

Along Bologna lines, all 15 countries, including those outside the European Higher Education Area, have adopted a two-cycle degree system and introduced bachelor and master degree programmes (3–4 plus 1–2 years). In some countries this system still co-exists, at least in some fields, with the traditional Soviet 5-year degree for specialists (e.g. in Russia and Turkmenistan). In terms of advanced qualifications, several countries, including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia and Kazakhstan, have abolished the second Soviet doctorate, so that their third cycle now only consists of one doctoral degree (PhD).

EHEA member states formally comply with the agreement requirements and have introduced quality assurance bodies for programme and/or institutional accreditation and established a system of credits (ECTS), all measures to support increasing mobility within the EHEA. This is a large-scale transformation for national higher education systems. Adoption of the new policies has created many tensions and uncertainties for higher education and employers’ communities, as the value and status of the degrees, especially at bachelor level, have been unclear. In many cases, traditional 5-year curricula were simply shortened in order to meet the new length of studies requirements, which generated a lot of discussion about “incomplete higher education” in the first cycle. In case of countries with binary systems, like Lithuania, the transition to the new system created challenges for colleges awarding professional degrees, especially in regard to internal quality assurance and the disjunction between professional bachelor degree and opportunities of further learning at master’s level (Leisyte et al. 2014).

Bologna transformation of the higher education systems for the post-Soviet states meant another wave of adoption of foreign/Western model of higher education with, for many, unclear purposes and advantages.

Internationalization

The USSR became a pioneer of a particular form of internationalization of higher education early in the twentieth century (Kuraev 2014). “Academic internationalization was continually a mission of the national government, reflecting general political strategy of the Soviet state”, and aimed at the “global promotion of the Soviet order” (p. 251). In preparation for the world revolution after the advent of global capitalism (imperialism), the Soviet government created a substantial programme of international education. This included full government support for international students to study in the USSR and very limited and highly controlled exchange programmes. Imposing the Soviet model of higher education on the other countries of the socialist bloc was also a part of Soviet international strategy. In the last years of the Soviet period it was already understood that the national economy was unable to continue to bear the costs of large-scale internationalization. But by the time of perestroika, the deteriorating Soviet system had opened up opportunities for genuine internationalization. The idea of joining global academia as an equal partner became appealing for Soviet academics. After decades of disseminating the Soviet model worldwide, as Kuraev points out, the new Soviet government suggested to study Western values and to adopt Western principles of academic freedom, institutional autonomy and self-governance. The “Open doors” policy resulted in international agreements and exchanges.

However, those policies had little financial support from the collapsing economy. Internationalization has increasingly become a tool of commercialization, offering a way to supplement institutional budgets with tuition fees from international students. In that respect, Russia was in a “privileged” position, as it inherited the international ties from the Soviet times and had HEIs in major cities where international students traditionally studied. However, also in other countries of the region internationalization has become an important aspect of the transformation of higher education.

Drawing on three case studies of internationalization in post-socialist countries, including former Soviet Georgia and Kazakhstan, Orosz and Perna (2016) found that internationalization has become an important dimension in these countries, especially in government rhetoric, but it lacks consistency and clarity in definitions. In both Georgia and Kazakhstan internationalization indicators became a part of accreditation procedures and the promotion of student mobility.

It can be argued that one of the key questions about internationalization in post-Soviet countries is what are its purposes, and to what extent are they related to the genuine improvement of higher education system by learning from other cultures? How is it interpreted by governments and academic communities of the region? To what extent does internationalization go beyond a single focus on commercialization or degree recognition? We argue that in many cases the role of internationalization is largely seen as a way to secure financial revenues for the sector, but also as an instrument of the further state control, linking internationalization with accreditation procedures and accountability.

International Assistance

An important role in post-Soviet transformations was played by international assistance. This included numerous Western government agencies, multilateral institutions (such as World Bank, OECD, Council of Europe), private non-profit foundations and exchange organizations (Open Society/Soros Institute, Ford Foundation, etc.) and also individual universities, consortia and professional associations (Johnson 1996). In the case of the international financial organizations international aid came as part of the package associated with conditional loans to the governments. Mostly the aid was focused on secondary school reform, but some was targeted towards higher education. International assistance contributed not only to the internationalization of higher education by supporting direct academic exchanges, the publication of international textbooks and literature and training programmes, but also helped to support infrastructure development and academic staff. In Central Asia these international agencies largely supported structural reforms, such as establishing national test systems (see chapter on Tajikistan). However, as Johnson (1996) notes for the case of Russia—and the point is applicable to other countries of the region—often both the reformers and the providers of international aid (including World Bank) were guided by idealized Western practices, rather than local needs and realities. International assistance agents underestimated the power of traditional institutional structures and inherited professional practices from the Soviet system, and the need to work with them, instead of trying to “develop” the systems as they did in educational programmes in other regions.

Summary of Reforms

Table 1.1 summarizes key reforms in higher education, which have been implemented in the post-Soviet period. It shows both commonalities and differences across countries. Even countries close to each other historically and culturally demonstrate different combinations of the reforms (e.g. the countries of Central Asia).

It is important to note that this comparative table does not include the research dimension of higher education systems. It mostly focuses on the teaching function. Although research has been a concern for many governments and international aid providers, it has not become a focus of reform in most of the countries. As the case studies in this book show, none of the systems were able to build a strong system of research universities. This is not only because of the chronic underfunding of research over the last 25 years but also because of the structural legacies inherited from the Soviet system, particularly its separation of teaching and research. Nevertheless, research funding has become an instrument of the state (see chapters on Lithuania, Russia), and this has contributed to the vertical differentiation of higher education systems.

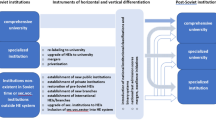

Landscape Changes

The changes in the landscape that took place from the 1990s on—note that some of the changes overlap—are as follows.

First, many new higher education institutions emerged, particularly the growth of non-state/private higher education was impressive (but note our earlier comment that the “privatization” of public higher education should not be overlooked). Obviously, under the communist regime, higher education provision was public and planned and regulated by the state. In the post-Soviet period, from the mid-1990s on, in many higher education systems, private initiatives loomed largely. In some countries, the number of institutions doubled between 1990 and now, in others growth was steeper, amounting to sixfold the number of institutions in 2015 compared to the beginning of the 1990s (see Table 1.1). Growth has been even more impressive if the dynamics between 1990 and 2015 are taken into account. Many more non-state higher education institutions emerged in that period, but governmental regulations—licensing and accreditation—led to the closing down of many private initiatives. The current private higher education institutions are generally smaller, focusing on economics, business studies and foreign language studies. They are often deemed of a lower reputation, although there are important exceptions found in some of the countries and it must also be acknowledged that the popularity of private higher education in many states was due to a lack of trust in public institutions and due to public institutions being reluctant or relatively slow to adjust to the new expectations.

Second, the growth of number of institutions is not only due to the emergence of non-state providers. Also, in all countries, the number of public institutions grew, although at a steadier pace than the number of privates. This was partly a spontaneous process with grass-root changes taking place (see also e.g. Tomusk 2004), including existing universities that set up branches elsewhere in the country (e.g. in Tajikistan, Russia, Armenia, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). Sometimes governments played a determining role in setting up new higher education institutions in regions that until then did not have universities or other higher education institutions. The governments of the new countries also established new universities to serve the needs of the states in such areas as security, public administration and international relationships.

A third change has been the upgrading of Soviet specialized institutes into universities: comprehensive or specialized (technical, medical, agricultural, pedagogical), in both cases with a greater number of fields of study (for specialized universities, going beyond their formal specialization). This resonates with an almost universal trend of “non-university” institutions trying to achieve university status noted in the literature by academic drift (e.g. Neave 1979; Birnbaum 1983). In post-Soviet countries, with the introduction of market-led or market-driven economies, many higher education institutions broadened their portfolio, particularly by adding “popular” disciplines and fields, like economics and business studies. In most higher education systems, there was a significant shift from enrolments in sciences and engineering towards economics, management and social sciences. As a consequence, many single-discipline institutions evolved into multidisciplinary institutions, even though many institutions kept their original names (or just changed from “institute” to “university”) and corporate identities. Although we do not have the exact data to support this point empirically, a corollary is that the differences between the higher education institutions—in terms of programme provision—became smaller over time. The Russian and Lithuanian cases particularly refer to the process of upgrading of some of the institutes and academies to universities. It should be noted however that this dynamic played out differently in the cases in this book: for example, the Azerbaijan case reports the blurring of boundaries between the three types, whereas other cases seem to suggest that the distinctions, even though they may be largely symbolic, remained (Tajikistan, Latvia).

A fourth change relates to vertical differentiation. Despite the norms and values of equity of the Soviet system, undeniably there were status differences between the institutions. Several chapters allude to the term “flagship” university, signalling there were particular institutions in their systems that were distinctive, for instance because they were educating the next generation of elites (see the chapter on Lithuania). Also some chapters argued that some disciplines had a higher status than others, giving subsequent prestige and status to the institution that specialized in those disciplines. In the period after independence, these status differences continued to exist and were even more profound. In some countries this is partly due to the attempts to (re)integrate research into the universities (in Soviet times carried out at the Academies of Sciences and sectoral institutes), with the level of research activities being used as a sign of excellence and reputation (in the case of Russia, there was an explicit excellence initiative). As noted, funding regimes and the introduction of national entrance exams have also affected the emergence of stronger vertical differences between HEIs in the region. In addition, some countries have employed various procedures to divide HEIs into different tiers by the level of awarded degrees: only first degree (bachelor) awarding institutions, bachelor and master institutions and three cycle HEIs (see chapters on Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyz Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Tajikistan, Ukraine). That inevitably contributed to the formal vertical differentiation in the sector.

Some other changes may have been less omnipresent and smaller in terms of impact, but nevertheless worth mentioning. In some countries, governments explicitly aimed at creating a binary structure (Lithuania and Estonia). It is interesting to see that such a policy solution was only visible in a minority of systems, whereas this solution was implemented quite often in European countries. Western European countries may have been in a different stage of development and more keen to “offload” universities and establish “cheaper” alternative pathways in higher education (see, e.g. Taylor et al. 2008), but also some Central and Eastern European countries adopted binary systems after independence (see Dobbins 2011).

Another small difference relates to the emergence of transnational or international providers (particularly in Armenia and Kyrgyzstan). Despite the small size of the segment of these new institutions, they occupy high prestige positions in the landscape. In many ways, the establishment of international providers reflects the geopolitical situation and contest within each country. For example in Belarus, there are no international providers, except for two Russian branches, while in Central Asia and Caucuses countries, the international HEIs come from not only Russia and the USA but also Turkey and other neighbouring countries.

In some countries, the Soviet structure has been changed through mergers. In Russia, for example, performance indicators have led the government to propose mergers and in Armenia there are recent plans for mergers. In Lithuania, mergers have been planned, but they have been largely unsuccessful. Some mergers have also been found in cases of Georgia, Estonia and Kazakhstan.

In the project it was not always possible to get data on the size of the institutions; however, the findings suggest that it was one of the ways in which the institutional landscape changed. For instance, in Russia system expansion has happened mostly due to the increase of the number of institutions, while in Belarus, the expansion has resulted in an increase of the size of institutions, rather than their number (Platonova 2016).

A final smaller difference is that in some countries existing educational providers, not yet belonging to the higher education fabric, were included into the higher education sector, for example, vocational schools in Ukraine. Alongside the latter change, we note a blurring of the distinctions between two parts of the tertiary sector: higher education and vocational colleges. The students’ pathways between these two levels became less restrictive.

Interestingly such an important feature of the institutional landscape as the separation of research and higher education (which manifested in the almost non-existence of research universities) was not changed significantly. Only few countries (e.g. Russia or Kazakhstan) made deliberate attempts to transform existing universities according to the model of the global research university (Mohrman et al. 2008) or establish new research universities.

This brings us to a final comment on the changes, already stressed in previous paragraphs, but important to stress again. Not all changes took place in all countries at the same level and, neither at the same time. There were remarkable differences between the countries, for instance with respect to the occurrence of mergers (to some extent reported in Azerbaijan and Russia), the phenomenon of international branch campuses (primarily in Armenia and Kyrgyzstan) and the emergence of private providers (not in Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). It is also noteworthy to share that in some countries the distinctions between private and public providers were not as sharp as they appear to be. In all countries the public universities appeared on the market competing with private universities for fee-paying students. In Kazakhstan, public universities were allowed to change their status into joint-stock companies, and in other countries, private higher education institutions were restricted in their operations by national regulations.

The Drivers of the Landscape Changes

As suggested earlier, it is not easy to distinguish drivers of landscape changes from contextual conditions, neither is it easy to disentangle major and minor drivers, but it is safe to argue that the foremost important driver has been the change from a planned economy towards societies in which market forces were incorporated. The overall response to the new economic setting was twofold. First, a new balance was sought between demand and supply. The Soviet mechanism of regulating demand and supply through advanced planning of numbers of seats in about 300 specializations and mandatory job placing was abandoned. Many narrow specializations were merged into broader areas. There was an increasing interest among students in disciplines and fields that were not offered in big numbers during Soviet times. This led to the transformation of many formerly highly specialized institutes and academies into multi-profile universities. The higher education institutions undertook action to broaden their supply, and governments contemplated whether new institutions needed to be set up to cater for the rising demand. And, importantly, the new economic context allowed for entrepreneurship in higher education, which led, on the one hand, to opening fee-paying places in public institutions and, on the other hand, to the emergence of many new (non-state/private) providers. Whereas the case studies may not have been fully clear on how initiatives for private higher education emerged, it appears that the ideas were developed mainly by those already working in public higher education institutions or by the former government or party servants seeking for status and income (e.g. see chapter on Belarus).

A second driver relates to international influences. Under this broad driver, several elements can be distinguished. International and supra-national agencies became involved in domestic policies. The case studies report the activities of the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the European Union’s Structural Funds. Powerful international NGOs like the “Open Society Institute” and Aga Khan Foundation also played a role in shaping national higher education systems. The international support came with strings attached in the form of certain conditions. These institutions, on the one hand, promoted neo-liberal ideas in financing higher education and in higher education governance. On the other hand, they promoted greater equality and access in higher education (e.g. through national university entrance exams). These policies usually did not have direct elements of the institutional landscape changes in the system except the support for private providers. They however had overall strong influence on the landscape through supporting policies that encourage competition and entrepreneurial behaviour of the universities.

Second, bilateral international relations and partnerships also played the role of driver of the changes in the institutional landscape. Branches of international universities or “national- international” universities like Russian-Armenian or British-Kazakh were established with the support of the respective governments, NGOs or business companies. These universities played an important role of setting new examples and models for “old” universities.

Third, the Bologna process figured to a large extent as an element of supranational influence. Most of the signatories have adjusted their higher education system by implementing a three-cycle degree structure, implementing a quality assurance system in line with the expectations formulated in the European Standards and Guidelines, and implementing diploma supplements and qualification frameworks. In addition, it seems reasonable to assume that the quality assurance and accreditation developments (partly under the influence of the Bologna Process) have paved the way for regulations to deal with minimum standards for higher education provision.

Demographic changes have been the fourth driver in the case studies, although it is difficult to pinpoint how exactly they impacted the changes. During the early years after independence, demographic factors in some countries contributed to the growth of unmet demand. That is, in that period a new balance was sought for—by governments, students and higher education institutions—between needs and supply. In some countries this dynamic was later dampened by decreasing birth rates and decreasing numbers of secondary school-leavers. These demographic changes interacted with governmental policies (particularly accreditation). That is, higher education institutions started to struggle to survive, partly due to stringent accreditation requirements and demand dropping because of a smaller pool of potential students.

The Role of Governments

One might expect that there should or could have been a significant role of the governments in shaping the higher education landscapes. Indeed the governments lead the development of the legislation that made possible the implementation of the reforms discussed above. One could agree with Carnoy et al. (2013) that the governments in most post-Soviet countries (except more authoritarian) were driven by global and national legitimacy agendas. It drove them to borrow some policies, to open access to higher education.

However, most case studies report that there was limited action from the government directly aimed at changes in the landscape. There is no country of the former Soviet Union that came with its own master plan to restructure the higher education system, to create a new differentiation of higher education institutions. Furthermore, many of the policies that were implemented were more reactive than deliberately proactive.

However, the governments of independent states did consider higher education to be an important tool of building new states. They established new (often specialized) universities to meet new human resources needs. Almost all states established their own military, police and public administration academies and higher education institutions to train cadres for diplomatic fields. Some governments established high prestige and quality higher education institutions in economics and finance. The governments also closed or transformed Soviet institutions that were useless for the independent countries like the Communist party schools and technical institutes that served the Union as a whole.

The need to strengthen the new national (ethnic) identity of young countries required language and culture policies in higher education. In 14 countries, the Russian language (that used to be the dominant language of instruction in higher education) was gradually replaced by local languages. It affected the vertical differentiation of universities. It also led in some cases to the establishment of new universities specialized in national culture and language. During the last years some countries added a new dimension into the vertical differentiation by establishing new or converting old institutions into world-class universities. Another set of the reforms enabled the transformation of existing universities into “niche” universities and establishment of the branches of universities. It contributed to both vertical and horizontal differentiation. The governments also supported the growth of new forms of delivery of education through part-time and distance programmes. It led to emergence of special type of institutions where these forms would be prevalent. The university branches in many countries radically changed the institutional landscape and opened a new level of the territorial accessibility in HE.

The governments also devised new legislation that defined new types of universities. They introduced national exams. Also, accreditation and licensing rules impacted the landscape to some extent. But overall—especially in the early years of independence—much change in the institutional landscape was due to grass-root innovations and entrepreneurship outside the government. Some cases explicitly point at a lack of capacity at the governmental level to develop strategies and policies for higher education in the new economic setting (e.g. Georgia and Armenia).

Interestingly the post-Soviet countries, unlike China, failed to concentrate the overwhelming majority of HEIs under the education ministry. The fact that higher education was steered not only by education ministers but that also ministers of health, defence, agriculture and so on were involved may have limited the scope for coherent governmental action as well.

Probably not a key reason, but it must be mentioned that some universities got their own specific acts and regulations, which may have further hampered the power of the governments or ministries.

In addition, it must be stressed that the economic crises in many countries may have led the governments to focus on more pressing issues than the shape, structure and size of their higher education systems. On the other hand, some countries had relatively stable economies built around the oil and gas industry. In some countries, the lack of attention to higher education was obviously also due to political constraints mentioned earlier. The second type of constraints relates to the political climate as such. Many case studies report on the ongoing practices of corruption and fraud in public administration (e.g. Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan) and obviously we cannot close our eyes to the democratic deficits in many of the countries. Transparency International reports annually on the corruption perceptions in countries across the globe, and it is important to note that only the Baltic states and Georgia are in the upper half and 11 countries appear in the bottom half of the ranking of 168 countries (2015). Also the Democracy Index (composed by the Economist Intelligence Unit) reports major deficits in the level of democracy in the former Soviet states, with seven of these being qualified as “authoritarian”. Undoubtedly, these features of the political climate affect the way policies are developed and implemented.

Structure of the Book

The discussion of the transformation of the institutional landscape in the region begins with an analysis of the institutional landscape in the USSR. Isak Froumin and Yaroslav Kouzminov note that by the revolution of 1917 the institutional landscape in imperial Russia has already been diverse. In the 1920s–1930s, Soviet economy took on the form of a mega-corporation aiming at industrialization and military power building, where higher education had a role of manpower training, among others. Specialization of its parts and their vertical, rather than horizontal, integration (between higher education and research, among various fields and disciplines) have become key features of that system. The authors argue that the system has remained almost unchanged since the 1930s until the 1980s.

Further the book presents the discussion of the institutional landscape transformation in 15 countries in alphabetical order. Each of the chapters provides an historical evolution of the national higher education systems since their beginning, showing continuities and discontinuities in their development. The chapters also try to place higher education developments in the larger societal context of major social transformations.

In the chapter on Armenia, Susanna Karakhanyan finds that the higher education landscape has become more diverse. It includes not only public and private institutions, but also intergovernmental and transnational institutions. An unusual development in the country is related to the introduction of a new legal form of public HEIs, in the form of foundations, which enjoy more financial freedoms. Transition to a market economy, resurrection of national identity and internationalization agenda developed by government are listed as most important factors behind the HE landscape changes. The recent decline in the number of HEIs (mostly, private) was a result of governmental initiatives to increase educational quality by strengthening accreditation and licensing (since 2008) as well as the extension of the national test to admissions in private sector (since 2012).

In Azerbaijan, as Hamlet Isakhanli and Aytaj Pashayeva note, an expanded HE system has also transformed into a more diverse system, which includes 5 public and 11 private comprehensive universities as well as a number of specialized HEIs. The institutional landscape has been also affected by governmental policies leading to increased vertical differentiation, including the early introduction of a distinction between different levels of HEIs (those awarding only bachelor degrees and those allowed to confer also master- and doctoral-level degrees) and by the use of institutional rankings based on admission test results.

Olga Gille-Belova and Larissa Titarenko argue in their chapter that the Belarusian higher education system expanded horizontally and changed vertically due to governmental policy and various rankings. The transformations at the inter-organizational level were also a result of a change in governmental policy rationales—from the logic of complementarity in the Soviet time to the logic of competition for students and resources. However, the government did not have the ambition to build a brand new higher education model. Rather it tried to adapt an existing Soviet model to the new political, economic, social and international reality.

In Georgia, as Lela Chakhaia and Tamar Bregvadze state, the higher education transformations can be divided into two periods: a chaotic development until 2004, associated with the expansion of both the public and especially the private sectors, followed by more strict governmental regulation aimed at achieving transparency and efficiency. However, the institutional landscape has become more diverse than in the Soviet time. Vertical differentiation has been strengthened by using national tests directly linked to the amount of governmental funding received.

In the chapter on Estonia, Triin Roosalu and Ellu Saar identify four periods in higher education development: from chaotic liberalization until 1993, to expansion and regulation in the next five years, then the Bologna reforms, and the more recent efficiency and excellence agenda. The transition from a demand-driven to supply-driven approach has been primarily determined by demographic decline. The authors argue that early post-Soviet years had more impact on the current state of higher education than did the entire socialist period. The current institutional landscape resembles the one of 1993. We might have to replace the concept of ‘post-socialism’ with the ‘post-post-socialism concept’.

In the case of Kazakhstan, Elise S. Ahn, John Dixon and Larissa Chekmareva find that despite different and in some ways comparatively radical reforms in higher education, which affected all dimensions of higher education—there were departures from the Soviet institutional types and the Soviet degree system; and there were changes in relation to educational funding, the privatization of public institutions, admission reforms, Bologna reforms, excellence programme and others—the administrative, teaching and learning legacies of the Soviet time continue to be prominent, and the government retains the full power to implement changes.

Jarkyn Shadymanova and Sarah Amsler argue that in the Kyrgyz Republic rapid system expansion did not result in an immediate diversification of institutional forms. Many Soviet institutions have kept their positions. Soviet and Bologna degree structures co-exist. However, diversification is taking place in many dimensions—public/private, central/regional, international/regional, horizontal/vertical and others. The authors find that diversification has become a strategy for survival of HEIs, where the best position is defined by historically accumulated prestige and association with governmental or international power.

In the case of Latvia, as Ali Ait Si Mhamed, Indra Dedze, Rita Kasa and Zane Cunska maintain, the expansion and diversification of the higher education system was driven largely by liberalization of the sector, and increased demand for higher education, as well as Latvia’s EU accession agenda. The factors differentiating the system vary from public/private, capital/regional, university/non-university sector to the language of instruction (English). The comparative autonomy of Latvian HEIs also contributes to the unique higher education pattern of the country.

Lithuanian higher education system has transformed from an elite system with one flagship university to a mass system that includes both university and non-university sectors, as Liudvika Leisyte, Anna-Lena Rose and Elena Schimmelpfennig argue. It experienced three periods of change: a period of regained autonomy and sporadic expansion; then further expansion, especially in the college sector, and changes related to the EU accession; and most recently, a period of increasing autonomy, competition and internationalization under conditions of demographic decline. During the post-Soviet period horizontal differentiation has been continuous, while vertical differentiation has strengthened, due to the introduction of a binary system, a private sector and competitive research funding. The role of the state, as authors point out, has shifted from a “sovereign state” to a “corporate state”. There is a somewhat high degree of HE organizational autonomy.

Alina Tofan and Lukas Bischof find that in the case of Moldova the pattern of higher education development can be described as ongoing consolidation. The first period of reform witnessed the disappearance of governance structures and led to the rapid expansion of HE system, which often under-delivered on quality. Since the demographic decline in 2005 and after, the government’s new admission rules and quality assurance initiatives resulted in a decrease in enrolments and in the number of private HEIs.

Russian higher education system sporadically expanded during the first period of independence, as Daria Platonova and Dmitry Semyonov demonstrate. However, from the 2000s onward, the government introduced a number of reforms which have contributed to a mostly vertical differentiation of the system. These include admission reform, new degree structures and new kinds of university status (the federal university and the national research university). Most recently, governmental policies were aimed at the “optimization” of the system by closing down and merging HEIs. Employing statistical analysis the authors interrogate various types of HEIs, showing that there are gaps between formal status and the actual institutional activity.

In Tajikistan, the first years of independence saw a dramatic civil war, as Alan J. DeYoung, Zumrad Kataeva and Dilrabo Jonbekova note. That delayed the process of enrolment growth until the 2000s. Before that the number of HEIs had begun to increase. The doubling of student numbers and the tripling of the numbers of HEIs constituted significant expansion of the system. The system has also diversified. Yet it still carries the Soviet structures and frameworks.