Abstract

The paper considers a no-arbitrage setting for pricing and relative value analysis of risky sovereign bonds. The typical case of an emerging market country (EM) that has bonds outstanding both in foreign hard currency (Eurobonds) and local soft currency (treasuries) is inspected. The resulting two yield curves give rise to a credit and currency spread that need further elaboration. We discuss their proper measurement and also derive and analyze the necessary no-arbitrage conditions that must hold. Then we turn attention to the CDS-Bond basis in this multi-curve environment. For EM countries the concept shows certain specifics both in theoretical background and empirical performance. The paper further focuses on analyzing these peculiarities. If the proper measurement of the basis in the standard case of only hard currency debt being issued is still problematic, the situation is much more complicated in a multi-curve setting when a further contingent claim on the sovereign risk in the face of local currency debt curve appears. We investigate the issue and provide relevant theoretical and empirical input.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Local currency debt of EM sovereigns became a hot topic both for practitioners and academics in the recent years. Major investment banks and asset managers consider it a separate asset class and publish regularly special local currency investment reports. A joint working group of IMF, WB, EBRD, and OECD demonstrated recently an official interest in a thorough investigation of this market segment and support for its development, thus forming a strict policy agenda. It was recognized that not only do the local bonds complete the market and thus bring market efficiency, but also they could act as a shock absorber to the volatile capital inflows. Furthermore, they provide flexibility to the governments in financing their budget deficit. However, these instruments are not well understood from a no-arbitrage point of view and a formal setting is lacking. Such a setting would provide not only a better picture for their inherent risk-return characteristics, but would also be an indispensable tool for market research and strategy. The aim of this paper is exactly to focus attention on the large set of open questions the local currency debt gives rise to and lay the ground for a formal relative value analysis with a special emphasis on the CDS-Bond basis.

The paper begins with our general modeling no-arbitrage approach under an HJM reduced credit risk setting. It serves as a basis and gives a financial engineering intuition about the nature of the problem. The default of the sovereign is represented as the first jump of a counting process. For the dynamics of the interest rates and the exchange rate we use jump diffusions controlling the jumps and correlations in a suitable way, so that we have high precision in capturing the structural macrofinancial effects. We derive the no-arbitrage conditions that must hold in that multi-curve environment and then analyze their informational content. Then we turn to an application related to correctly extracting the credit and currency spreads and measuring the CDS-Bond basis on a broader scope. This provides basic building blocks for relative value trades under presence of the local currency yield curve which could serve as an additional pillar.

The literature on integrating the foreign and domestic debt of a risky sovereign in a consistent way is at a nascent stage both from an academic and practitioners’ point of view. Related technically but different in essence is the work of Ehlers and Schönbucher [9] who give a reduced form model for CDS of an obligor denominated in different currencies which accounts for dependence between the exchange rate and the credit spread. Eberlain and Koval [8] give a high generalization of the cross-currency term structure models, but similarly they deal only with hard currencies. Regarding the CDS-Bond basis, Berd et al. [2] provide a thorough analysis of the shortcomings of the Z-spread as a risky spread metric.Footnote 1 Alizalde et al. [10] further discuss the issue and provide extensive simulations. Interesting new measures for the basis are given in Bernhard and Mai [3] which need further elaboration and development. However, all these references deal with the single-curve case with an extension to the multi-curve case pending.

2 Local Currency Bonds No-Arbitrage HJM Setting

In this section we first lay the foundations in brief for pricing of risky debt in a general reduced form setting. Then we add the local currency debt into the picture and discuss the risky spreads. We conclude by derivation and analysis of the no-arbitrage conditions.

2.1 Risky Bonds Under Marked Point Process

The first task is to model default in a suitable way. We start with the most general formulation and then modify it appropriately. We consider a filtered probability space \((\varOmega ,\left( G_{t}\right) _{t\ge 0},P)\) which supports an n-dimensional Brownian motion \( W^{P}=(W_{1},W_{2},\ldots ,W_{n})\) under the objective probability measure P and a marked point process \(\mu :\left( \varOmega ,B(R^{+}),\varepsilon \right) \rightarrow R^{+}\) with markers \(\left( \tau _{i}\text {,}\;X_{i}\right) \) representing the jump times and their sizes in a measurable space \(\left( E,\varepsilon \right) \), where \(E=\left[ 0,1\right] \) and by \(\varepsilon \) we denote the Borel subsets of E. We assume that \(\mu (\omega ;dt,dx)\) has a separable compensator of the form:

where \(h(\omega ;t)=\int _{R^{+}}\upsilon \left( \omega ;t,dx\right) \) is a \( G_{t\text { }}\)measurable intensity and the marks have a conditional distribution of the jumps of \(F_{t}(\omega ;dx).\) Thus, we have the identity \(\int _{E}F_{t}\left( \omega ;dx\right) =1\). Furthermore, we can define the total loss function \(L(\omega ;t)=\int _{0}^{t}\int _{E}l(\omega ;s,x)\mu (\omega ;ds,dx)\) and the recovery \(R(\omega ;t)=1-\int _{0}^{t}\int _{E}l(\omega ;s,x)\mu (\omega ;ds,dx)\). The function \( l(\omega ;t,x)\) scales the marks in a suitable way, and having control over it, we can define it such that our model is tractable enough. We define also the sum of the jumps by \(S(\omega ;t)=\int _{0}^{t}\int _{E}x\mu (\omega ;ds,dx)\) and their number by \(N(\omega ;t)=\int _{0}^{t}\int _{E}\mu (\omega ;ds,dx).\)

Effectively, the marked point process as a sequence of random jumps \(\left( \tau _{i}\text {,}X_{i}\right) \) is characterized by the probability measure \( \mu (\omega ;dt,dx),\) which gives the number of jumps with size dx in a small time interval of dt. The compensator \(\upsilon \left( \omega ;t,dx\right) \) provides a full probability characterization of the process. It incorporates in itself two effects. On one hand, we have the intensity \({}\), which gives the conditional probability of jump of the process in a small time interval of dt incorporating the whole market information up to t. On the other hand, we have the conditional distribution \(F_{t}(\omega ;dx)\) of the markers X in case of a jump realization.

We can look at the jumps of the marked point process as sequential defaults of an obligor at random times \(\tau _{i}\) that lead to losses \(X_{i}\) at each of them. They can also be considered a set of restructuring events leading to losses for the creditors. Under this general setting, the prices of the riskless and risky bonds are given by:

-

Riskless bond:

$$\begin{aligned} P(t,T)=E^{Q}\left( \exp \left( -\int _{t}^{T}r(s)ds\right) |G_{t}\right) =\exp \left( -\int _{t}^{T}f(t,s)ds\right) \end{aligned}$$(1) -

Risky bond:

$$\begin{aligned} P^{*}(t,T)= & {} E^{Q}\left( \exp \left( -\int _{t}^{T}r(s)ds\right) R(\omega ;T)|G_{t}\right) \nonumber \\= & {} R(t)\exp \left( -\int _{t}^{T}f^{*}(t,s)ds\right) , \end{aligned}$$(2)where r(t), f(t, T), and \(f^{*}(t,T)\) are the riskless spot, riskless forward, and risky forward rates respectively.

Depending on how we specify the convention of recovery, we can get further simplification of the formulas. However, this should be well motivated and come either from the legal definitions of the debt contracts or their economic grounding.

Under a recovery of market value (RMV) setting, default is a percentage mark down, q, from the previous recovery. So we have \(R(\omega ;\tau _{i})=\left( 1-q(\omega ;\tau _{i},X_{i})\right) R(\omega ;\tau _{i}-)\) and \( l(\omega ;\tau _{i})\) has the form \(l(\omega ;\tau _{i})=\) \(-q(\omega ;\tau _{i},X_{i})\times R(\omega ;\tau _{i}-).\) This definition allows us to write:

and if we assume no jumps of the intensity and the risk-free rate at default times (contagion effects), we have no change for the risk-free bond pricing formula and for the risky one and as in [13] we get:

Note that within this setting there is no “last default”. The intensity is defined for the whole marked point process and not just for a concrete single default time, so it does not go to zero after default realizations. This combined with the fact that intensity is continuous makes the market filtration \(G_{t}\) behave like a background filtration in the pricing formulas. So we can avoid using the generalized Duffie, Schroder, and Skiadas [7] formula. Furthermore, we can denote \(q_{e}(t)=\int _{E}q\left( \omega ;t,x\right) F_{t}(dx)\) to be the expected loss. So we have that the pricing formula is dependent on the generalized intensity \(h(t)q_{e}(t).\) Due to the multiplicative nature of the last expression, only from market information, as discussed in Schönbucher (2003), we cannot distinguish between the pure intensity effect h(t) and the recovery induced one \( q_{e}(t)\).

Under a recovery of par (RP) setting, in case of default, the recovery is a separate fixed or random quantity independent of the default indicator and the risk-free rate. So we have \(E=\{0,1-R\left( \omega \right) \}\) and \( \upsilon \left( \omega ;dt,dx\right) =h(\omega ;t)(1-R_{e})dt\) with \( R_{e}=E^{Q}(R\left( \omega \right) \mid G_{t}).\) Since we have just one jump, we can write:

The bond price is:

In contrast to RMV, here, as discussed in Schönbucher (2003), he can distinguish between the pure intensity and recovery induced effects.

2.2 Model Formulation

In this section we develop our HJM model for pricing of local and foreign currency bonds of a risky country. However, before this being done formally, it is essential to elaborate on the nature of the problem. Although we do not put here explicitly macrofinancial structure, but just proxy it by jumps and correlations, it, by all means, stays in the background and must be conceptually considered.

2.2.1 General Notes

A risky emerging market country can have bonds denominated both in local and foreign currency that give rise to two risky yield curves and risky spreads—credit and currency. Generally, the latter arise due to the possibility of the respective credit events to occur and their severity. To investigate them, formal assumptions are needed both on their characteristics and interdependence.

We will consider that the two types of debt have different priorities. The country is first engaged to meeting the foreign debt obligation from its limited international reserves. The impossibility of this being done leads to default or restructuring. In both cases, we have a credit event according to the ISDA classification. The foreign debt has a senior status. The spread that arises reflects the credit risk of the country. It is a function of: (1) the probability of the credit event to occur; (2) the expected loss given default; (3) the risk aversion of the market participants to the credit event.

The domestic debt economically stands differently. It reflects the priority of the payments in hard currency and it incurs instantly the losses in case of default of the country. So this debt is the first to be affected by a default and is subordinated. Technically, the credit event can be avoided under a flexible exchange rate regime because the country can always make a debt monetization and pay the amounts due in local currency taking advantage of the fact that there is no resource constraint on it. However, the price for this is inflation pick-up and exchange rate depreciation. This leads to real devaluation of the domestic debt. It is exactly the seigniorage and the dilution effect that cause the loss in the value.Footnote 2 This resembles the case of a firm issuing more equity to avoid default. The spread of the domestic debt over the foreign one forms the currency spread. Its nature is very broad, and it is not only due to the currency mismatch. Namely, it is a function of: (1) the probability of the credit event to occur and the need for monetization; (2) the negative side effect of the credit event on the exchange rate by a sudden depreciation of the latter; (3) the volatility of the exchange rate; (4) the expected depreciation of the exchange rate without taking into consideration the monetization; (5) the risk aversion of market participants to the credit event and the need for monetization, the sudden exchange rate depreciation and its size; (6) the risk aversion of the market participants to the volatility of the exchange rate. All these effects are captured by our model.

2.2.2 Multi-currency Risky Bonds Model

We use the setting of Sect. 2.1 modified to a multi-currency debt. Firstly, we consider the case of no monetization and then analyze the case with monetization. Secondly, to avoid using an additional marked point process, and thus a second intensity, the default on the foreign debt is modeled indirectly. Namely, we assume that default on domestic debt leads to default on foreign debt, but due to the different priority of the two, we have just different losses incurred, respectively recoveries. This means that by controlling recoveries we control default and the inherent subordination without imposing too much structure. If the default on the domestic debt is so strong that it leads to a default on the foreign debt as well, we incur zero recovery on the domestic debt and some positive one on the foreign debt. If the insolvency is mild, we have a loss only on the domestic debt, so we incur some positive recovery on the domestic debt and a full recovery on the foreign debt. Thirdly, for notational purposes, we take as a benchmark Germany and EUR as the base hard currency. Lastly, we employ the recovery of market value assumption. The reason for this is twofold. On one hand, in that way, we are consistent with the HJM methodology of Schönbucher [12] for a single risky curve under RMV and produce parsimonious no-arbitrage conditions for the extension to a multi-curve environment. On the other hand, as pointed out in Bonnaud et al. [5], for bonds denominated in a different currency than the numerator employed in discounting, the RMV assumption should be the working engine. Their argument is exactly as ours above, in case of default, the sovereign would rather dilute by depreciating the exchange rate and thus the remaining cash flows of the bond produce in essence the RMV structure. Moreover, rather than using EUR denominated bonds, we could take advantage of the CDS quotes and produce synthetic bonds having an RMV recovery structure. Using them is actually preferable for empirical work since major academic studies argue that it is the CDS market that first captures the market information about the credit risk stance of the risky sovereign. Furthermore, with a few exceptions, if the EM sovereigns have in most cases both well developed local currency treasury markets and are subject to CDS quotation, they do have only few Eurobonds outstanding. Figure 1 represents the typical situation the risky sovereign faces.

Mathematical formulation We continue with the model setup. Firstly, we give the suitable notation and assumptions. Then we move to the derivation of the no-arbitrage conditions and the pricing.

-

Notation

\(f_{EUR}(t,T)\)—nominal forward rate, EUR, Ger.

\(f_{EUR}^{*}(t,T)\)—nominal forward rate, EUR, EM

\(f_{LC}^{*}(t,T)\)—nominal forward rate in LC, EM

\(r_{EUR}(t)\)—nominal short rate, EUR, Ger.

\(r_{EUR}^{*}(t)\)—nominal short rate, EUR, EM

\(r_{LC}^{*}(t)\)—nominal short rate in LC, EM

\(h_{EUR}^{*}(t,T)=f_{EUR}^{*}(t,T)-f_{EUR}(t,T)\)—credit spr., EM

\(h_{LC,EUR}^{*}(t,T)=f_{LC}^{*}(t,T)-f_{EUR}^{*}(t,T)\)—currency spr., EM

\(h_{LC}^{*}(t,T)=f_{LC}^{*}(t,T)-f_{EUR}(t,T)\)—general currency spr., EM

\(P_{EUR}(t,T)=\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{EUR}(t,s)ds)\)—bond, EUR, Ger.

\(P_{f,EUR}^{*}(t,T)=R_{f,EUR}(t)\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{EUR}^{*}(t,s)ds)\)—for. bond price., EUR, EM

\(P_{d,LC}^{*}(t,T)=R_{d,LC}(t)\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{LC}^{*}(t,s)ds)\)—dom. bond price., LC, EM

\(B_{EUR}(t)=\exp (\int _{0}^{t}r_{EUR}(s)ds)\)—bank account, EUR, Ger.

\(B_{f,EUR}^{*}(t)=R_{f,EUR}(t)\exp (\int _{0}^{t}r_{EUR}^{*}(s)ds)\)—for. bank account, EUR, EM

\(B_{d,LC}^{*}(t)=R_{d,LC}(t)\exp (\int _{0}^{t}r_{LC}^{*}(s)ds)\)—dom. bank account, LC, EM

X(t)—exchange rate, EUR for 1 LC, \(\widetilde{X}(t)\)—exchange rate, LC for 1 EUR

\(R_{f,EUR}(t)\)—bond recovery, EUR, EM, \(R_{d,LC}(t)\)—bond recovery, LC, EM

We use the asterisk to denote risk, the first letter (d or f) to denote domestic or foreign debt, and finally the currency of denomination is shown as EUR or LC.Footnote 3

-

Currency denominations

\(P_{d,EUR}^{*}(t,T)=X(t)P_{d,LC}^{*}(t,T)\)—dom. bond, EUR

\(P_{f,LC}^{*}(t,T)=\widetilde{X}(t)P_{f,EUR}^{*}(t,T)\)—for. bond, LC

\(B_{d,EUR}^{*}(t)=X(t)B_{d,LC}^{*}(t)\)—dom. bank account, EUR

\(B_{f,LC}^{*}(t)=\widetilde{X}(t)B_{f,EUR}^{*}(t)\)—for. bank account, LC

-

Intensities

$$ \begin{array}{ll} \text {Foreign debt, EUR:} &{} \\ { \ \text {Intensity:}} &{} {h}_{EUR}{(t)=h(t)} \\ { \ \text {Compensator:}} &{} {h}_{EUR}{(t)q} _{e,EUR}{(t)=h(t)\int _{E}q}_{f,EUR}\left( \omega ;t,x\right) {F }_{t}{(dx)} \\ \text {Domestic debt, LC:} &{} \\ { \ \text {Intensity:} } &{} {h}_{LC}{(t)=h(t)} \\ \ { \text {Compensator:}} &{} {h}_{LC}{(t)q}_{e,LC}{\small (t)=h(t)\int _{E}q}_{d,LC}\left( \omega ;t,x\right) {F}_{t}{(dx) } \end{array} $$The compensator (generalized intensity) characterizes default. Controlling in a suitable way the recovery, we can control the compensator and thus the default event. We turn attention now to the dynamics of the instruments under consideration.

-

Forward rates

\(df_{EUR}(t,T)=\alpha _{EUR}(t,T)dt+\mathop {\textstyle \sum }\nolimits _{i=1}^{n}\sigma _{EUR,i}(t,T)dW_{i}^{P}(t)\)

\(df_{EUR}^{*}(t,T)=\alpha _{EUR}^{*}(t,T)dt+\mathop {\textstyle \sum }\nolimits _{i=1}^{n}\sigma _{EUR,i}^{*}(t,T)dW_{i}^{P}(t)\)

\(+{\int _{E}}\delta _{EUR}^{*}(x,t,T)\mu (dx,dt)\)

\(df_{LC}^{*}(t,T)=\alpha _{LC}^{*}(t,T)dt+\mathop {\textstyle \sum }\nolimits _{i=1}^{n}\sigma _{LC,i}^{*}(t,T)dW_{i}^{P}(t)\)

\(+{\int _{E}}\delta _{LC}^{*}(x,t,T)\mu (dx,dt) \)

We assume that in case of default there is a market turmoil leading to a jump in both curves. At maturity T, the EUR curve jumps by a size of \( {\int _{E}}\delta _{EUR}^{*}(x,t,T)\mu (dx,dt),\) and that of the local currency by \({\int _{E}}\delta _{LC}^{*}(x,t,T)\mu (dx,dt).\) The terms \(\delta _{EUR}^{*}(x,t,T)\) and \(\delta _{LC}^{*}(x,t,T)\) show the jump sizes of the respective curves for every maturity. As indicated at the beginning of the section, everywhere we will work under the market filtration \(G_{t}\) so both the Brownian motions and the point process are adapted to it.

-

Recoveries

\(\frac{dR_{f,EUR}(t)}{R_{f,EUR}(t)}=-\int _{E}q_{f,EUR}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt)\)

\(\frac{dR_{d,LC}(t)}{R_{d,LC}(t)}=-\int _{E}q_{d,LC}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt) \)

After each default we have a devaluation of the respective bond by an expected value of \({\int _{E}}q_{f/d}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt)\). The stochasticity of the loss is captured by the random jump size q(., .) as elaborated in Sect. 2.1.

-

Bank accounts

\(\frac{dB_{EUR}(t)}{B_{EUR}(t)}=r_{EUR}(t)dt\)

\(\frac{dB_{f,EUR}^{*}(t)}{B_{f,EUR}^{*}(t)}=r_{EUR}^{*}(t)dt-\int _{E}q_{f,EUR}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt)\)

\(\frac{dB_{d,LC}^{*}(t)}{B_{d,LC}^{*}(t)}=r_{LC}^{*}(t)dt -\int _{E}q_{d,LC}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt) \)

-

Exchange rate

\(\frac{dX(t)}{X(t)}=\) \(\alpha _{X}(t)dt+\mathop {\textstyle \sum }\nolimits _{i=1}^{n}\sigma _{X,i}(t)dW_{i}^{P}(t)-{\small \int _{E}}\delta _{X}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt) \)

We assume that in case of default the market turmoil causes an exchange rate devaluation by \({\int _{E}}\delta _{X}(x,t)\mu (dx,dt).\)

-

Bond prices

\(P_{EUR}(t,T)=\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{EUR}(t,s)ds)=E^{Q^{f}}(\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}r_{EUR}(s)ds)|G_{t})\)

\(P_{f,EUR}^{*}(t,T)=R_{f,EUR}(t)\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{EUR}^{*}(t,s)ds)\)

\(=E^{Q^{f}}(\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}r_{EUR}(s)ds)R_{f,EUR}(T)|G_{t})\)

\(P_{d,EUR}^{*}(t,T)=P_{d,LC}^{*}(t,T)X(t)=R_{d,LC}(t)X(t)\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}f_{LC}^{*}(t,s)ds)\)

\(=E^{Q^{f}}(\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}r_{EUR}(s)ds)R_{d,LC}(T)X(T)|G_{t}) \)

It must be emphasized that the effects of exchange rate, recovery, and the expected devaluation sizes are incorporated in the respective forward rates of the bonds. Furthermore, the expectations are taken under \(Q^{f}\), the foreign risk-neutral measure.

-

Arbitrage

Under standard regularity conditions, for the system to be free of arbitrage, all traded assets denominated in euro must have a rate of return \( r_{EUR}\) under \(Q^{f}\). This means that the processes:

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{P_{EUR}(t,T)}{B_{EUR}(t)},\frac{B_{f,EUR}^{*}(t)}{B_{EUR}(t)}, \frac{P_{f,EUR}^{*}(t,T)}{B_{EUR}(t)},\frac{B_{d,LC}^{*}(t)X(t)}{ B_{EUR}(t)},\frac{P_{d,LC}^{*}(t,T)X(t)}{B_{EUR}(t)} \end{aligned}$$must be local martingales under \(Q^{f}\). For our purposes being martingales would be enough.

Taking the stochastic differentials of the upper expressions, omitting the technicalities to the appendix, we can get the respective no-arbitrage conditions.

-

Spreads:

$$\begin{aligned} r_{EUR}^{*}(t)-r_{EUR}(t)=h(t)\varphi _{q_{f,EUR}}(t) \end{aligned}$$(5.1)$$\begin{aligned} \begin{array}{l} r_{LC}^{*}(t)-r_{EUR}^{*}(t)=-\alpha _{X}(t)-\phi (t)\sigma _{X}(t) \nonumber \\ +h(t)(\varphi _{\delta _{X}}(t)-\varphi _{q_{d,LC},\delta _{X}}(t)+\varphi _{q_{d,LC}}(t)-\varphi _{q_{f,EUR}}(t)) \end{array} \end{aligned}$$(5.2) -

Drifts:

\(\alpha _{EUR}(t,T)=\sigma _{EUR}(t,T)\int _{t}^{T}\sigma _{EUR}(t,v)dv-\sigma _{EUR}(t,T)\phi (t)\)

\(\alpha _{EUR}^{*}(t,T)=\sigma _{EUR}^{*}(t,T)\int _{t}^{T}\sigma _{EUR}^{*}(t,v)dv-\sigma _{EUR}^{*}(t,T)\phi (t)\)

\(+h_{EUR}(t)\varphi _{\theta _{EUR}^{*}}^{q_{f,EUR},\delta _{X}}(t)\)

\(\alpha _{LC}^{*}(t,T)=\sigma _{LC}^{*}(t,T)\int _{t}^{T}\sigma _{LC}^{*}(t,v)dv-\sigma _{LC}^{*}(t,T)\phi (t)-\sigma _{LC}^{*}(t,T)\sigma _{X}(t,T)\)

\(+h_{LC}(t)\varphi _{\theta _{LC}^{*}}^{q_{d,LC},\delta _{X}}(t)\),

where we have used the notation:

\(\theta _{EUR}^{*}=\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}\delta _{EUR}^{*}(x,t,s)ds)\) , \(\theta _{LC}^{*}=\exp (-\int _{t}^{T}\delta _{LC}^{*}(x,t,s)ds)\)

\(\varphi _{a.b,\ldots }^{x,y,\ldots }(t)=\int _{E}(ab\ldots )((1-x)(1-y)\ldots )\varPhi (t,x)F_{t}(dx) \)

and used vector notation and scalar products where necessary for simplicity.

By \(\varPhi (t,x)\) and \(\phi (t)\) we denoted the Girsanov’s kernels of the counting process and the Brownian motion respectively when changing the probability measure from P to \(Q^{f}.\) The term \(\varphi (t)\) represents the scaled expected jump sizes of the counting process. We can give the interpretation that \(\phi (t)\) is the market price of diffusion risk and \( \varphi (t)\) is the market price of jump risk. Parametrizing the volatilities and the market prices of risk, as well as imposing suitable dynamics for h(t), we give a full characterization of our system. Furthermore, the intensity could be a function of the underlying processes of the rates, so we could get correlation between the intensity, the interest rates, and the exchange rate.

Spreads diagnostics from a reduced form point of view It is important to give a deeper interpretation of the no-arbitrage conditions and see which factors drive the credit and currency spreads. Despite the heavy notation, the analysis actually goes fluently. The drift equations give the modified HJM drift restrictions. The slight change from the classical riskless case is due to the jumps that arise. Equation (5.1) shows that the credit risk is proportional to the intensity of default and the scaled expected LGD by the coefficient controlling the risk aversion. The higher they are, the higher the spread is. Equation (5.2) gives the currency spread. It arises due to two main reasons. Firstly, the intensity of default and the difference between the two LGDs in local currency and euro, scaled by the coefficient for the risk aversion, act as in the previous case. They also make explicit the subordination. Secondly, the expected local currency depreciation, its volatility, and the risk aversion to diffusion risk act similarly to the standard uncovered interest parity (UIP) relationship. The higher they are, the higher the spread is. It is both important and interesting to note that inflation does not appear directly and it influences the spreads, as the next section shows, only through a secondary channel.

Monetization The analysis so far considered a loss of \(1-R_{d,LC}(T)\) on default of the domestic debt. However, if a full monetization is applied, then we would have \(R_{d,LC}(T)=1\) and thus \(\varphi _{q_{d,LC}}(t)=0\) and \(\varphi _{q_{d,LC},\delta _{X}}(t)=0\). If such a monetary injection is neutral to nominal values, it is certainly not to real ones. Devaluation arises due to the negative market sentiment following the default and the higher amount of money in circulation. Its effect can be measured differently based on what we take as a base—the price index or the exchange rate. Most naturally, we can expect both of them to depreciate due to the structural macrolinks that exist between these variables. For quantifying the amount we would need a macromodel which is beyond the scope of the reduced form model presented. The latter only shows what characteristics the market prices in general without imposing concrete macrolinks among them. Depending on what the base is, we would have a direct estimation of certain type of indicators and an indirect one of the rest up to their structural influence on the former. If the inflation is taken as a base, then we would have the comparison of inflation indexed bonds to the non-indexed ones. The spread between them would give an estimate for the expected inflation. Unfortunately, such an analysis is unrealistic due to the fact that such bonds are issued very rarely by emerging market countries. If the exchange rate is taken as a base, then we would have the comparison of domestic debt bonds to foreign debt bonds. The spread between them would give an estimate for the currency risk and the devaluation effect. The estimate for the inflation would be indirect and based on hypothetical structural links.

Whether the country would monetize or declare a formal default is based on strategic considerations. It is a matter of structural analysis which option it would take. By all means, its decision is priced. In case of default, the pricing formula is Eq. (5.2). In case of monetization, we would have a jump in the exchange rate. Let us denote its size by \(\widehat{\delta }_{X}\). It will be different from the no-monetization one, \(\delta _{X}\), due to the different regimes that are followed, and we would thus get:

There is no a priori no-arbitrage argument that \(\varphi _{\widehat{\delta }_{X}}(t)=\varphi _{\delta _{X}}(t)-\varphi _{q_{d,LC},\delta _{X}}(t)+\varphi _{q_{d,LC}}(t)\) must hold so that the two scenarios are equivalent.Footnote 4 The only information we get from the market is an estimate for the generalized intensity being \(h(t)\varphi _{ \widehat{\delta }_{X}}(t)\) or \(h(t)(\varphi _{\delta _{X}}(t)-\varphi _{q_{d,LC},\delta _{X}}(t)+\varphi _{q_{d,LC}}(t))\) but not knowing which possible scenario will be realized.

3 CDS-Bond Basis

3.1 General Notes

The setting we built gives us an alternative for evaluating the CDS-Bond basis. This is represented in Fig. 1. There the LC zero-coupon yield curve is built by employing local currency treasuries and an appropriate smoothing method. The EUR zero-coupon yield curve is built by employing CDS quotes with the maths represented in the sequel. Along with the curves, there are few Eurobonds represented in light blue colored dots. Both credit and currency spreads can be computed for them employing a standard Z-spread methodology. Despite its various shortcomings, as discussed in Berd et al. [2] and Elizalde et al. [10], it allows us to have a certain measure for the spreads and it is widely accepted by practitioners. Subtracting from the yield curves’ implied credit and currency spreads the bond implied spreads, we get two alternative specifications for the CDS-Bonds basis. Several things need a comment.

Firstly, the two basis measures are not equal by default. The one representing the credit spread is subject to Z-spread measurement based on a parallel shift of the benchmark curve. So it depends on the whole benchmark curve and has nothing to do with the LC one. Vice versa, the basis implied by the LC curve is subject to Z-spread measurement based on a parallel shift of the LC curve. So it depends on the whole LC curve, but has nothing to do with the benchmark one. This provides intuition how the introduction of the LC curve brings additional information in the picture and provides more market completeness that must be utilized in relative value trades.

Secondly, as mentioned above, the EUR curve is built by utilizing CDS quotes. As shown below, in the procedure employed, an assumption is needed for the recovery scheme. What it should be depends on our purposes. On one hand, if we would like to just extract the credit and currency spreads from the yield curves and calibrate a reduced form model,Footnote 5 it would be convenient to employ the setting from Sect. 2. So an RMV assumption for the EUR curve is the most appropriate one since the same assumption is imposed also for the LC curve and when subtracting the corresponding zero yields, we subtract apples from apples. On the other hand, if we like to extract the basis, we must be careful since the Eurobonds are priced under a firmly established RP assumption. So for a standard calculation via a Z-spread based on the benchmark curve we need an RP built EUR curve to be consistent. With the many problems of the Z-spread, it would be definitely bad to add further ones coming from a recovery assumption inconsistency which would only further contribute to an imprecise basis measurement. For a calculation via a Z-spread based on the LC curve, we should not use the RMV LC curve but a modified one. From the RMV LC curve we need to build an RP one and then compute the Z-spread and the basis to be consistent.

3.2 Technical Notes

Here we provide the technical notes regarding the above discussion.

-

EUR curve

Using OIS differential discounting as in Doctor and Gouldenss [6], we could modifyFootnote 6 the standard CDS bootstrap procedure of ISDA time t the \(T-\)maturity default probabilities \(p_{EUR}^{R\text { }}(t,T)\) under a recovery assumption of R. Then we would get in a straightforward way the EUR zero coupon yields (ytm) and credit spreads (spr) under RMV and RP:

-

RMV:

spr\(_{EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)=-\frac{(1-R)\log (1-p_{EUR}^{R}(t,T))}{T-t}\)

ytm\(_{EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)=\) spr\(_{EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)+\exp (-y_{EUR}(t,T)(T-t)) \)

-

RP:

spr\(_{EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)=-\frac{\log (Rp_{EUR}^{R}(t,T)+1-p_{EUR}^{R}(t,T))}{ T-t}\)

ytm\(_{EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)=\) spr\(_{EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)+\exp (-y_{EUR}(t,T)(T-t)), \)

where \(y_{EUR}(t,T)\) is the \(T-\)maturity zero yield of the riskless benchmark curve (e.g. German bunds).

-

-

LC curve

-

RMV:

ytm\(_{LC}^{RMV,R}(t,T)\)–observed from the market

spr\(_{LC,EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)=\) ytm\(_{LC}^{RMV,R}(t,T)-\)ytm\(_{EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)\)

\(p_{LC}^{R\text { }}(t,T)=1-\exp (-\frac{\text {spr}_{LC,EUR}^{RMV,R}(t,T)}{1-R }(T-t)) \)

-

RP:

spr\(_{LC,EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)=-\frac{\log (Rp_{LC}^{R}(t,T)+1-p_{LC}^{R}(t,T))}{ T-t}\)

ytm\(_{LC}^{RP,R}(t,T)=\) spr\(_{LC,EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)+\)ytm\(_{EUR}^{RP,R}(t,T)\)

-

Note that similarly to the EUR curve procedure, the LC curve one relies on the premise that both the RMV and RP cases must share the same \(p_{LC}^{R \text { }}(t,T),\) which stands for the probability of default on the LC debt. However, according to the analysis we had in Sect. 2 on the no-arbitrage conditions, due to the monetization, such probability actually does not formally exist. Here it is only a derived quantity since although we assume the same point process as a driver of default on both the LC and EUR debt, we can control the compensator by changing the recoveries. However, we could just take the formulas above for the RP spread as definitions. Taking the limit case of zero EUR debt, they would be entirely consistent to the RP in case of EUR debt, thus providing a justification for our method.

3.3 CDS-Bond Basis Empirics

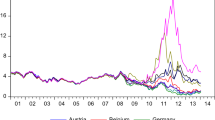

For illustration we provide visualization of the Z-spread measured basis according to the two alternative ways for a set of European EM countries. They are chosen so that they have both Eurobonds outstanding in EUR and a liquid LC curve. The data sources are: Bloomberg, Datastream, and CBonds. We build the LC curves by employing the Bloomberg BFV curves. Since they are par curves, see Lee [11], we transform them to zero-coupon yield ones. For spreads extraction we use both EUR and USD denominated CDS. We give preference to the former, but in case of missing quotes we use USD quotes instead by making a quanto adjustment using cross currency basis swaps. The countries under focus are: Bulgaria (BGN), Czech Rep. (CZK), Hungary (HUF), Lithuania (LTL), Poland (PLN), Romania (RON), and Slovakia (SKK).

Since there are plenty of bonds outstanding, aggregate measures are presented based on duration weighting. The events: 1—GM turmoil of May 09, 2005, 2—Liquidity crisis of August 09, 2007, 3—Bear Sterns default of March 14, 2008, 4—Lehman default of September 15, 2008, 5—Greek turmoil of April 23, 2010, 6—August 5, 2011—the US rating downgrade, 7—06 May, 2012—ECB refi-rate woes are marked by the vertical dashed lines.

The short conclusion from the patterns in Fig. 2 is that the bonds provide important input for extracting the credit and currency spreads. The two alternative basis formulations preserve general shape similarity, but still give different results that should not be underestimated. This is not surprising since the outcome is driven by the difference in shapes between the benchmark and the LC curves. Market strategists and arbitrage traders have a large scope for interpretations and trades design.

4 Conclusion

The paper considers the credit and currency spreads of a risky EM country. The necessary no-arbitrage conditions are derived and their informational content is analyzed. An application of the setting is made to proper building of the foreign and local currency yield curves of a sovereign as well as to providing ideas for relative value diagnostics in a multi-currency framework. In that direction, an alternative measure for the CDS-Bond basis is discussed when the local currency curve is employed as a pillar. The aim of the paper is both to point out the rich opportunities the setting gives for market-related research that could be of use to strategists and policy officers and to make the first several steps toward investigating such opportunities.

Notes

- 1.

The Z-spread represents a simple shift of the discounting risk-free curve so that the price of the risky bond is attained.

- 2.

This pattern can be observed historically for almost all EM countries resorting to a galloping inflation to avoid a nominal domestic debt default. The Russian default of 1998 somehow seems to be a partial notable exception where there was along with the inflation surge an actual default on certain ruble (RUR) bonds—GKOs and OFZs.

- 3.

It must be further noted that we actually used standard definitions for the risky forward rates as in Schönbucher [12]. Namely, \(f_{EUR/LC}^{*}(t,T)=-\frac{\partial }{\partial T}\log P_{f,EUR/d,LC}^{*}(t,T)\) with terminal conditions \(P_{f,EUR/d,LC}^{*}(T,T)=\) \(R_{f,EUR/d,LC}(T)\). The risky bank accounts economically just represent a unit of currency invested at the respective short rates and continuously rolled over accounting for any default losses. However, since the forward rates, resp. the bonds, are our basic modeling object, it would be more precise to consider the bank accounts derived quantities from them similar to Björk et al. [4] without going here deeper into the modified technical details.

- 4.

This is a delicate issue. As indicated, a further structural analysis is needed for a complete answer. The crucial point is that the two scenarios affect in a different way the monetary base. It will have a neutral effect on the macro variables in general and the risky spreads in particular only in case the economy is at the macro potential. Exactly when that is not the case, we can expect that the two scenarios will not be equivalent. A further elaboration on these issues from a structural point of view could be found in Yordanov [15, 16].

- 5.

- 6.

The OIS discounting should be given a special comment since there is still no consensus on how to bootstrap OIS swaps to form the discount factors for the CDS swap bootstrap. The problem comes from the presence of gaps for certain maturities. A possible specification is given in West [14].

References

Bai, J., Collin-Dufresne, P.: The CDS-Bond Basis During the Financial Crisis of 2007–2009. WP SSRN.2024531 (2011)

Berd, A., Mashal, R., Wang, P.: Definig, Estimating and Using Credit Term Structures. Lehman Brothers Research (2004)

Bernhart, G., Mai, J.: Negative Basis Measurement: Finding the Holy Scale. XAIA Investment Research (2012)

Björk, T., Di Masi, G., Kabanov, Y., Runggaldier, W.: Towards a general theory of bond markets. Financ. Stoch. 1, 141–174 (1997)

Bonnaud, J., Carlier, L., Laurent, J., Vila, J.: Sovereign recovery schemes: discounting and risk management issues. In: 29th International Conference of the French Finance Association (AFFI) (2012)

Doctor, S., Goulden, J.: Differential Discounting for CDS. JPMorgan Europe Credit Research (2012)

Duffie, D., Schroder, M., Skiadas, C.: Recursive Valuation of Defaultable Securities and the Timing of Resolution Uncertainty. WP 195, Kellog Graduate School of Management, Department of Finance, Northwestern University (1994)

Eberlein, E., Koval, N.: A cross-currency Lévy market model. Quant. Financ. 6, 465–480 (2006)

Ehlers, P., Schönbucher, P.: The Influence of FX Risk on Credit Spreads. WP, ETH Zurich (2006)

Elizalde, A., Doctor, S., Saltuk, Y.: Bond-CDS Basis Handbook. JPMorgan Research (2009)

Lee, M.: Bloomberg fair value market curves. In: International Bond Conference, Taipei (2007)

Schönbucher, P.: Term structure of defaultable bonds. Rev. Deriv. Stud. Special Issue: Credit Risk 2(2/3), 161–192 (1998)

Schönbucher, P.: Credit Derivatives Pricing Models: Models, Pricing and Implementation. Wiley (2003)

West, G., Post-crisis methods for bootstrapping the yield curve. WP, Financial Modelling Agency (2011). http://finmod.co.za/OIS%20Curve.pdf

Yordanov, V.: Risky Sovereign Capital Structure: Fundamentals. WP SSRN.2349370 (2015)

Yordanov, V.: Risky Sovereign Capital Structure: Macrofinancial Diagnostics. WP SSRN.2600238 (2015)

Yordanov, V.: Multi-currency Risky Sovereign Bonds Arbitrage. WP SSRN.2349324 (2015)

Acknowledgements

The KPMG Center of Excellence in Risk Management is acknowledged for organizing the conference “Challenges in Derivatives Markets - Fixed Income Modeling, Valuation Adjustments, Risk Management, and Regulation”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Here we briefly elaborate on the derivation of Eqs. (5.1) and (5.2). Applying the Girsanov’s theorem and the Ito’s Lemma for jump diffusions to Eq. (2), we get the dynamics:

Furthermore, we have the dynamics of the exchange rate:

So using the no-arbitrage conditions and equating the expected local drifts to the risk-free rate, we get the results shown.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Yordanov, V. (2016). Inside the EMs Risky Spreads and CDS-Sovereign Bonds Basis. In: Glau, K., Grbac, Z., Scherer, M., Zagst, R. (eds) Innovations in Derivatives Markets. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, vol 165. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33446-2_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33446-2_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-33445-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-33446-2

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)