Abstract

Purpose of Review

Epidemiologists frequently must handle competing events, which prevent the event of interest from occurring. We review considerations for handling competing events when interpreting results causally.

Recent Findings

When interpreting statistical associations as causal effects, we recommend following a causal inference “roadmap” as one would in an analysis without competing events. There are, however, special considerations to be made for competing events when choosing the causal estimand that best answers the question of interest, selecting the statistical estimand (e.g., the cause-specific or subdistribution) that will target that causal estimand, and assessing whether causal identification conditions (e.g., conditional exchangeability, positivity, and consistency) have been sufficiently met.

Summary

When doing causal inference in the competing events setting, it is critical to first ascertain the relevant question and the causal estimand that best answers it, with the choice often being between estimands that do and do not eliminate competing events.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Competing risk regression models for epidemiologic data. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):244–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp107.

Andersen PK, Abildstrom SZ, Rosthoj S. Competing risks as a multi-state model. Stat Methods Med Res. 2002;11(2):203–15. https://doi.org/10.1191/0962280202sm281ra.

Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data, second edition. Wiley series in probability and statistics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002.

Hernan MA, Robins JM. Causal inference: what if. Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton; 2020.

Petersen ML, van der Laan MJ. Causal models and learning from data: integrating causal modeling and statistical estimation. Epidemiology. 2014;25(3):418–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000078.

Ahern J. Start with the “C-word,” follow the roadmap for causal inference. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(5):621. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304358.

Andersen PK, Geskus RB, de Witte T, Putter H. Competing risks in epidemiology: possibilities and pitfalls. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(3):861–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyr213.

Schisterman EF, Silver RM, Perkins NJ, Mumford SL, Whitcomb BW, Stanford JB, et al. A randomised trial to evaluate the effects of low-dose aspirin in gestation and reproduction: design and baseline characteristics. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27(6):598–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppe.12088.

•• Cole SR, Hudgens MG, Brookhart MA, Westreich D. Risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):246–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwv001. This paper was the first to extend the potential outcomes framework to competing risk settings and is an excellent deep-dive into this fundamental measure of outcome occurrence. (Although we recognize that this paper is more than 3 years old, it is a key citation.).

• Cole SR, Lau B, Eron JJ, Brookhart MA, Kitahata MM, Martin JN, et al. Estimation of the standardized risk difference and ratio in a competing risks framework: application to injection drug use and progression to AIDS after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(4):238–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwu122. This companion paper to Risk discusses many of the same topics but in the context of a practical application. Lesko.

•• Lesko CR, Lau B. Bias due to confounders for the exposure-competing risk relationship. Epidemiology. 2017;28(1):20–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000565. This highly approachable paper uses simulation to demonstrate important concepts related to controlling for confounding when there are competing events and was the first paper to show that we ought to control for confounders of the exposure-competing event relationship.

•• Young JG, Stensrud MJ, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Hernan MA. A causal framework for classical statistical estimands in failure-time settings with competing events. Stat Med. 2020;39:1199–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8471. While more technical than the current paper, this work covers essentially all important topics related to estimating causal effects when there are competing events.

Sarfati D, Blakely T, Pearce N. Measuring cancer survival in populations: relative survival vs cancer-specific survival. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):598–610. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyp392.

Thompson CA, Zhang ZF, Arah OA. Competing risk bias to explain the inverse relationship between smoking and malignant melanoma. Eur J Epidemiol. 2013;28(7):557–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9812-0.

Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Cole SR, Edwards JK, Naimi AI, Munoz A. Hidden imputations and the Kaplan-Meier estimator. Am J Epidemiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwaa086.

Hernan MA. The hazards of hazard ratios. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):13–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c1ea43.

Aalen OO, Johansen S. An empirical transition matrix for non-homogeneous Markov chains based on censored observations. Scand J Stat. 1978;5(3):141–50.

Geskus RB. Data analysis with competing risks and intermediate states. Chapman & Hall/CRC Biostatistics Series. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015.

Collett D. Competing risks. Modelling survival data in medical research. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015. p. 405–28.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144.

Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The statistical analysis of failure time data. New York: Wiley; 1980.

Ishwaran H, Gerds TA, Kogalur UB, Moore RD, Gange SJ, Lau BM. Random survival forests for competing risks. Biostatistics. 2014;15(4):757–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/biostatistics/kxu010.

Lau B, Cole SR, Gange SJ. Parametric mixture models to evaluate and summarize hazard ratios in the presence of competing risks with time-dependent hazards and delayed entry. Stat Med. 2011;30(6):654–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4123.

Gerds TA, Scheike TH, Andersen PK. Absolute risk regression for competing risks: interpretation, link functions, and prediction. Stat Med. 2012;31(29):3921–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5459.

Binder N, Gerds TA, Andersen PK. Pseudo-observations for competing risks with covariate dependent censoring. Lifetime Data Anal. 2014;20(2):303–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10985-013-9247-7.

Neophytou AM, Picciotto S, Brown DM, Gallagher LE, Checkoway H, Eisen EA, et al. Estimating counterfactual risk under hypothetical interventions in the presence of competing events: crystalline silica exposure and mortality from 2 causes of death. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(9):1942–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy077.

Cole SR, Richardson DB, Chu H, Naimi AI. Analysis of occupational asbestos exposure and lung cancer mortality using the g formula. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(9):989–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws343.

Cortese G, Andersen PK. Competing risks and time-dependent covariates. Biom J. 2010;52(1):138–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/bimj.200900076.

Cortese G, Gerds TA, Andersen PK. Comparing predictions among competing risks models with time-dependent covariates. Stat Med. 2013;32(18):3089–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5773.

Robins JM, Wasserman L. On the impossibility of inferring causation from association without background knowledge. In: Glymour C, Cooper G, editors. Computation, causation, and discovery. Cambridge: AAAI Press/The MIT Press; 1999. p. 305–21.

Lau B, Lesko C. Missingness in the setting of competing risks: from missing values to missing potential outcomes. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5(2):153–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-018-0142-3.

Nevo D, Nishihara R, Ogino S, Wang M. The competing risks cox model with auxiliary case covariates under weaker missing-at-random cause of failure. Lifetime Data Anal. 2018;24(3):425–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10985-017-9401-8.

Bakoyannis G, Siannis F, Touloumi G. Modelling competing risks data with missing cause of failure. Stat Med. 2010;29(30):3172–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4133.

Lu K, Tsiatis AA. Multiple imputation methods for estimating regression coefficients in the competing risks model with missing cause of failure. Biometrics. 2001;57(4):1191–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.01191.x.

Lau B, Cole SR, Moore RD, Gange SJ. Evaluating competing adverse and beneficial outcomes using a mixture model. Stat Med. 2008;27(21):4313–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3293.

Nicolaie MA, van Houwelingen HC, Putter H. Vertical modelling: analysis of competing risks data with missing causes of failure. Stat Methods Med Res. 2015;24(6):891–908. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280211432067.

VanderWeele TJ. Concerning the consistency assumption in causal inference. Epidemiology. 2009;20(6):880–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181bd5638.

Grambauer N, Schumacher M, Dettenkofer M, Beyersmann J. Incidence densities in a competing events analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(9):1077–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwq246.

Edwards JK, Cole SR, Chu H, Olshan AF, Richardson DB. Accounting for outcome misclassification in estimates of the effect of occupational asbestos exposure on lung cancer death. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(5):641–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt309.

Keil AP, Mooney SJ, Jonsson Funk M, Cole SR, Edwards JK, Westreich D. Resolving an apparent paradox in doubly robust estimators. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(4):891–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx385.

Karn MN. An inquiry into various death-rates and the comparative influence of certain diseases on the duration of life. Ann Eugenics. 1931;4(3–4):279–302.

Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV Jr, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34(4):541–54.

Pintilie M. Competing risks: a practical perspective. Statistics in practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2006.

Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med. 2017;36(27):4391–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7501.

Westreich D, Edwards JK, Rogawski ET, Hudgens MG, Stuart EA, Cole SR. Causal impact: epidemiological approaches for a public health of consequence. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(6):1011–2. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303226.

Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389–430. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2712.

Andersen PK, Keiding N. Interpretability and importance of functionals in competing risks and multistate models. Stat Med. 2012;31(11–12):1074–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4385.

Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause-specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(6):648–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant R01 HD093602 and National Institutes of Health grant K01 AA028193.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Right

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

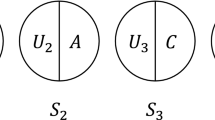

Figures: Fig. 1 was designed by the authors and has not been included in previously published work.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Epidemiologic Methods

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rudolph, J.E., Lesko, C.R. & Naimi, A.I. Causal Inference in the Face of Competing Events. Curr Epidemiol Rep 7, 125–131 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-020-00240-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-020-00240-7