Abstract

Background

The Weber effect states that adverse event (AE) reporting tends to increase in the first 2 years after a new drug is placed onto the market, peaks at the end of the second year, and then declines. However, since the Weber effect was originally described, there has been improvement in the communication of safety information and new policies regarding the reporting of AEs by healthcare professionals and consumers, prompting reassessment of the existence of the Weber effect in the current AE reporting scenario.

Objectives

To determine the AE reporting patterns for new molecular entity (NME) drugs and biologics approved in 2006 and to examine these patterns for the existence of the Weber effect.

Methods

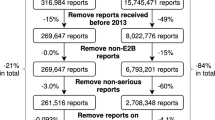

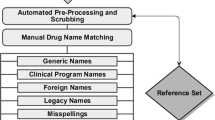

Publicly available FDA Adverse Event Reporting System data were used to assess the AE reporting patterns for a 5-year period from the drug’s approval date. The total number of annual reports from all sources, based on the report date, was plotted against time (in years).

Results

In the period from 2006 to 2011, a total of 91,187 AE reports were submitted for 19 NMEs approved in 2006. The highest number of AE reports were submitted for varenicline tartrate (N = 47,158) and the lowest number for anidulafungin (N = 161). Anidulafungin was reported to have the highest proportion of death reports (36 %) and varenicline tartrate the lowest proportion (1.7 %). The classic Weber pattern was not observed for any of the 19 NMEs approved in 2006. While there was no one predominant pattern of AE report volume, we grouped the drugs into four general categories; the majority of drugs had either a continued increase in reports (Category A 31.6 %) or an N-pattern with reporting reaching an initial peak in year 2 or 3, declining and then beginning to climb again (Category B 42.1 %).

Conclusions and relevance

There have been numerous changes in AE reporting, particularly a huge increase in overall annual report volume, since the Weber effect was first reported. Our results suggest that a Weber-type reporting pattern should not be assumed in the design or interpretation of analyses based on AE reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Weber JCP. Epidemiology of adverse reactions to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Adv Inflamm Res. 1984;6:1–7.

Hartnell NR, Wilson JP. Replication of the Weber effect using postmarketing adverse event reports voluntarily submitted to the United States Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(6):743–9.

Wallenstein EJ, Fife D. Temporal patterns of NSAID spontaneous adverse event reports: the Weber effect revisited. Drug Saf. 2001;24(3):233–7.

McAdams MA, Governale LA, Swartz L, Hammad TA, Dal Pan GJ. Identifying patterns of adverse event reporting for four members of the angiotensin II receptor blockers class of drugs: revisiting the Weber effect. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17(9):882–9.

Hartnell NR, Wilson JP, Patel NC, Crismon ML. Adverse event reporting with selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(10):1387–91.

Weiss-Smith S, Deshpande G, Chung S, Gogolak V. The FDA drug safety surveillance program: adverse event reporting trends. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):591–3.

Auerbach M, Kane RC. Caution in making inferences from FDA’s Adverse Event Reporting System. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(11):922–3.

Bailie GR. Comparison of rates of reported adverse events associated with i.v. iron products in the United States. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(4):310–20.

Owens J. 2006 drug approvals: finding the niche. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(2):99–101.

Food and Drug Administration. Approved Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm111350.htm. Accessed 12th March 2013.

Staffa JA, Dal Pan GJ. Regulatory innovation in postmarketing risk assessment and management. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):555–7.

Silverman E. Pfizer did not report Chantix side effects correctly? http://www.pharmalot.com/2011/05/pfizer-did-not-report-chantix-side-effects-correctly/.

de Graaf L, Fabius MA, Diemont WL, van Puijenbroek EP. The Weber-curve pitfall: effects of a forced introduction on reporting rates and reported adverse reaction profiles. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25(6):260–3.

Food and Drug Administration. Lucentis label and approval history. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.Label_ApprovalHistory#apphist. Accessed 12th March 2013.

Moore TJ, Furberg CD, Glenmullen J, Maltsberger JT, Singh S. Suicidal behavior and depression in smoking cessation treatments. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27016.

Author’s contributions

Pankdeep Chhabra and Xing Chen: study design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation; they had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Sheila Weiss: study design, interpretation of data, and manuscript preparation. Qscan-FDA was provided for this research through an in-kind donation from Druglogic, Inc. to the Center for Drug Safety, University of Maryland School of Pharmacy.

Conflict of interest disclosure

Pankdeep Chhabra: Now an employee of Sanofi Pasteur (a vaccine company). However, the employment began after the completion of the first submission of this manuscript.

Xing Chen: No conflict of interest disclosure

Sheila Weiss: Consulted for directly, served on the advisory board, served on a grant or contract (as a principal investigator or as an investigator), consulted with their legal representatives as an expert, and/or worked as an employee in the last 3 years: University of Maryland, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, Georgetown University, National Cancer Institute, DrugLogic Inc., United Healthcare/Optum, Pfizer, Bayer, Esai, Novartis, Amgen, Biogen Idec, and Roche.

Source of funding and support

No funding or support was available for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chhabra, P., Chen, X. & Weiss, S.R. Adverse Event Reporting Patterns of Newly Approved Drugs in the USA in 2006: An Analysis of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System Data. Drug Saf 36, 1117–1123 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0115-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0115-x