Abstract

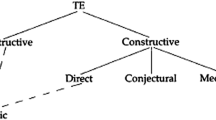

The growing literature on philosophical thought experiments has so far focused almost exclusively on the role of thought experiments in confirming or refuting philosophical hypotheses or theories. In this paper we draw attention to an additional and largely ignored role that thought experiments frequently play in our philosophical practice: some thought experiments do not merely serve as means for testing various philosophical hypotheses or theories, but also serve as facilitators for conceiving and articulating new ones. As we will put it, they serve as ‘heuristics for theory discovery’. Our purpose in the paper is two-fold: (i) to make a case that this additional role of thought experiments deserves the attention of philosophers interested in the methodology of philosophy; (ii) to sketch a tentative taxonomy of a number of distinct ways in which philosophical thought experiments can aid (and historically have aided) theory discovery, which can guide future research on this role of thought experiments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

It is commonly held that a particular kind of (irreducible) mental state termed ‘intuition’ or, perhaps less often and less controversially, ‘intuitive judgment’, is what is doing the actual “work” in thought experimentation. A preliminary remark pertains to this. By using the term ‘intuitive judgment’, we wish not to commit to any theoretical possibility currently on offer—on our intended usage it simply refers to those judgments that participants of the debate on thought experiments take themselves to be discussing. That usually means immediate responses to thought experiments. However, the focus of our paper is not so much the role of these judgments in thought experiments, but rather the role of thought experiments, more generally, in philosophical methodology.

For criticism of the use of intuition in philosophy, see for instance Cummins (1998), Devitt (1994), Hintikka (1999), Kornblith (2002, 2005, 2006); and perhaps most prominently in recent years the attack from the experimental philosophy movement, see e.g. Machery et al. (2004); Stich (1998); Weinberg et al. (2001); Nichols et al. (2003); and Swain et al. (2008).

It is tempting to put the distinction between these two roles of thought experiments in terms of Hans Reichenbach’s famous distinction between the ‘context of discovery’ and the ‘context of justification’ (Reichenbach 1938). However, because of the complicated and controversial history of this distinction, we will stick to the more neutral description of it as two roles, and elaborate on particulars and varieties as needed.

To say that this role has been ignored in the literature is not to say that theorists have been unaware of it—we make no claim to that effect. We merely note that explicit discussion of the role in the literature is so far more or less absent, and argue that the role deserves attention.

In part inspired by Bealer (1998), who contrasts rational and physical intuitions as elicited by thought experimentation in philosophy and natural sciences, respectively, (although Bealer thinks the term ‘thought experiment’ should be abandoned in philosophy).

An alternative take on how to understand the discovery-functioning of scientific thought experiments is put forward by Kuhn. According to Kuhn (1977), scientific thought experimentation serves as a discovery-tool in that it produces new understanding via a reconceptualization of old empirical data. It is unclear, however, what the relevance of this approach would be for understanding the creative potential of philosophical thought experiments.

In fact, Clark (1963) himself shows by method of counterexample that ‘Justified True Belief + No False Ground’ is not an adequate analysis of knowledge, before advancing his own analysis (‘Justified True Belief + No Essential False Ground’) (see below).

See Clark (1963).

In fact, both the ‘Justified True Belief + No False Ground’ analysis and ‘Justified True Belief + No Essential False Ground’ analysis generated a plethora of responses. Other counterexamples, some of which intended to target the sufficiency of not only one, but both additions, include: Lehrer’s ‘Non-inferential Nogot’ (1965,1970); Lehrer’s ‘Clever Reasoner’ (1974); Feldman’s ‘Testimony Nogot’ (1974); Scheffler’s ‘Stopped Clock’ (1965) following Russell (1948); Chisholm’s ‘Sheep in the Field’ (1966); Skyrms’ ‘Sure Fire Match’ (1967) and Rozeboom’s ‘Togethersmith’ (1967). Saunders and Champawat (1964) together with Skyrms (1967) question the necessity of the additions.

And similarly constructed thought experiments; Gettier’s original cases would work just as well. Our project here is not to claim that Skyrms’ thought experiment is the single origin of the various theories of defeaters. In fact, we are sure it is not.

References

Bealer, G. (1998). Intuition and the autonomy of philosophy. In DePaul & Ramsey (Eds.), Rethinking intuition (pp. 201–239). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefiled Publishers.

Brown, J. R. (1986). Thought experiments since the scientific revolution. International Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 1, 1–15.

Brown, J. R. (1991a). Laboratory of the mind: Thought experiments in the natural sciences. London: Routledge.

Brown, J. R. (1991b). Thought experiments: A platonic account. In T. Horowitz & G. Massey (Eds.), Thought experiments in science and philosophy (pp. 119–128). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Brown, J. R., & Fehige, Y. (2010). Thought experiments. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 25(1):135–142.

Chisholm, R. M. (1966). Theory of knowledge. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Clark, M. (1963). Knowledge and grounds: A comment on Mr. Gettier’s paper. Analysis, 24, 46–48.

Cohnitz, D. (2003). Modal skepticism: Philosophical thought experiments and modal epistemology. In F. Stadler (Ed.), The Vienna circle and logical positivism [Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook 10/2002] (pp. 281–296). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Craig, E. (1990). Knowledge and the state of nature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Cummins, R. (1998). Reflection on reflective equilibrium. In M. DePaul & W. Ramsey (Eds.), Rethinking intuition: The psychology of intuition and its role in philosophical inquiry. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Devitt, M. (1994). The methodology of naturalistic semantics. Journal of Philosophy, 91, 545–572.

Feldman, R. (1974). An alleged defect in Gettier counter-examples. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 52, 68–69.

Gale, R. M. (1991). On some pernicious thought-experiments. In T. Horowitz & G. Massey (Eds.), Thought experiments in science and philosophy. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Gettier, E. L. (1963). Is justified true belief knowledge? Analysis, 23, 121–123.

Gendler, T. (2004). Though experiments rethought—and repercieved. Philosophy of Science, 71, 1152–1163.

Hall, N., & Paul, L. A. (2013). Causation: A user’s guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, J. (1999). The Emperor’s new intuitions. Journal of Philosophy, 96, 127–147.

Horgan, T., & Timmons, M. (1992). Troubles on moral twin earth: Moral queerness revived. Synthese, 92, 221–260.

Häggqvist, S. (1996). Thought experiments in philosophy. Stockholm: Almqvist and Wiksell.

Ichikawa, J., & Jarvis, B. (2009). Thought-experiment intuitions and truth in fiction. Philosophical Studies, 142(2), 221–246.

Jackson, F. (1986). What Mary didn’t know. Journal of Philosophy, 83, 291–295.

Kornblith, H. (2002). Knowledge and its place in nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kornblith, H. (2005). Replies to A. Goldman, M. Kusch and W. Talbott. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71, 427–441.

Kornblith, H. (2006). Appeals to intuition and the ambitions of epistemology. In S. Heatherington (Ed.), Epistemology futures (pp. 10–25). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. (1977). A function for thought experiments. In T. Kuhn (Ed.), The essential tension: Selected studies in scientific tradition and change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lehrer, K. (1965). Knowledge, truth and evidence. Analysis, 25, 168–175.

Lehrer, K. (1970). The fourth condition of knowledge: A defense. Review of Metaphysics, 24, 122–128.

Lehrer, K. (1974). Knowledge. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Machery, E., Mallon, R., Nichols, S., & Stich, S. (2004). Semantics, cross-cultural style. Cognition, 92, B1–B12.

McGinn, C. (1977). Charity, interpretation, and belief. Journal of Philosophy, 74, 521–535.

Nichols, S., Stich, S., & Weinberg, J. (2003). Metaskepticism: Meditations in ethno-epistemology. In S. Luper (Ed.), The skeptics (pp. 227–247). Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Norton, J. (1991). Thought experiments in Einstein’s work. In T. Horowitz & G. Massey (Eds.), Thought experiments in science and philosophy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Norton, J. (2002). Why thought experiments do not transcend empiricism. In C. Hitchcock (Ed.), Contemporary debates in the philosophy of science (pp. 44–66). Oxford: Blackwell.

Norton, J. (2004). On thought experiments: Is there more to the argument? Proceedings of the 2002 Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association, Philosophy of Science, 71, 1139–1151.

Putnam, H. (1973). Meaning and reference. Journal of Philosophy, 70, 699–711.

Rawls, J. (1999). A theory of justice. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Reichenbach, H. (1938). Experience and prediction. Analysis of the foundations and structure of knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rozeboom, W. W. (1967). Why I know so much more than you do. American Philosophical Quarterly, 4, 281–290.

Russell, B. (1948). Human knowledge: Its scope and limits. New York: Allen and Unwin.

Saunders, J. T., & Champawat, N. (1964). Mr. Clark’s definition of “Knowledge”. Analysis, 25, 8–9.

Scheffler, I. (1965). Conditions of knowledge. Chicago: Scott Foresman.

Skyrms, B. (1967). The explication of “X knows that p”. Journal of Philosophy, 64, 373–389.

Stich, S. (1998). Reflective equilibrium, analytic epistemology and the problem of cognitive diversity. Synthese, 74, 391–413.

Swain, S., Alexander, J., & Weinberg, J. (2008). The instability of philosophical intuitions: Running hot and cold on truetemp. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 76, 138–155.

Thomson, J. (1971). A defence of abortion. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 1, 47–66.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, T. (2007). The philosophy of philosophy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Weinberg, J., Shaun, N., & Stich, S. (2001). Normativity and epistemic intuitions. Philosophical Topics, 29, 429–460.

Zagzebski, L. (1994). The inescapability of Gettier problems. Philosophical Quarterly, 44, 65–73.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at Aarhus University (2012; 2014), University of Copenhagen (2013), and University of Southern Denmark (2013). We are grateful to the audiences on those occasions for helpful discussion, in particular Jens Christian Bjerring, Jessica Brown, Otávio Bueno, Jacob Busch, Michael Devitt, Jane Friedman, Mikkel Gerken, Raul Hakli, Brian Leiter, Hannes Leitgeb, Anna-Sara Malmgren, Stephen Mumford, Nikolaj Nottelmann, Samuel Schindler, Johanna Seibt, Asger Steffensen, Anand Vaidya, and Timothy Williamson. We are also grateful to John Hawthorne and number of referees for this journal for their useful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. Research for this paper was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research, as part of the project ‘Epistemology of Modality: Six Investigations’. Support was also received from the John Templeton Foundation, and the ‘New Insights and Directions for Religious Epistemology’-project at the University of Oxford, which one of the authors visited during Hilary and Trinity terms of 2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Praëm, S.K., Steglich-Petersen, A. Philosophical thought experiments as heuristics for theory discovery. Synthese 192, 2827–2842 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0684-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-015-0684-6