Abstract

The traditional solutions to the Sleeping Beauty problem say that Beauty should have either a sharp 1/3 or sharp 1/2 credence that the coin flip was heads when she wakes. But Beauty’s evidence is incomplete so that it doesn’t warrant a precise credence, I claim. Instead, Beauty ought to have a properly imprecise credence when she wakes. In particular, her representor ought to assign \(R(H\!eads)=[0,1/2]\). I show, perhaps surprisingly, that this solution can account for the many of the intuitions that motivate the traditional solutions. I also offer a new objection to Elga’s restricted version of the principle of indifference, which an opponent may try to use to collapse the imprecision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

I don’t find the psychological defenses moving. First, it’s not clear that imprecise credences are information-theoretically simpler. The Traditional Bayesian can also claim only to be providing an theory of ideal rational belief, which wouldn’t be subject to the kinds of claims that the psychological defenses employ.

Pust (2011) convincingly argues that we don’t yet have a way to make sense of conditionalization for temporally indexical information. Here I assume Beauty can conditionalize on wake, which does contain temporally indexical information. As Pust points out though, the standard arguments surrounding Sleeping Beauty assume that we can conditionalize on such information, and I will do that as well. Interestingly, though Pust may reject my argument for that reason, he ends up endorsing a position on Sleeping Beauty that is noticeably similar to the view I endorse, except without the imprecision.

Strictly speaking, this is not right. Both subjective and objective Imprecise Bayesian positions are subject to the worries presented by Van Fraassen (2006), which require the Imprecise Bayesian claim at most that one ought adopt a collection that ranges widely over (but doesn’t completely cover) the intervals compatible with one’s evidence.

The notation here is meant to be the natural extension of the notation introduced above, so that \(R(A|B)=\{P(A|B)|P\in R\}\).

Note that the Imprecise Bayesian need not accept this argument from Elga, but doing so decreases the amount of imprecision in Beauty’s credal state, making the Imprecise Bayesian’s task harder. The argument for the Imprecise position I endorse does not rely on accepting Elga’s claim.

This is because one could be certain that today is not Tuesday while being certain that there is a waking on Tuesday, and Beauty can’t rule out these credences as the proper response to her evidence. Of course, there is some information that Beauty could have learned about these uncentered possibilities that should affect her credences in the centered propositions, e.g. that there is no waking on Tuesday. Certainly her credence that today is Tuesday ought not exceed her credence that there is a Tuesday waking. That said, the particular information wake2 doesn’t inform her credence in those centered propositions.

Beauty’s credence dilating upon learning wake is not an objectionable feature of the Imprecise option. In fact, notice the similarity between the dilation that occurs here and the dilation that occurs in the case Joyce (2010a, pp. 295–296) discusses called “Complementarity,” where Joyce shows that it’s a virtue of the Imprecise Bayeisan framework that it can capture more sophisticated doxastic attitudes than what can be captured just in terms of the intervals that are occupied.

A popular proposed alternative here is to extend the range of credence functions to include infinitesimals and assign each possibility infinitesimal credence. Easwaran (2014) shows the mistake in this proposal.

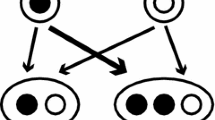

I’m assuming that we have no information about the biases of the black/white coins except that the bias of one of them \(\beta \) is the opposite of the other \(1-\beta \).

See Joyce (2010a) for an extended defense of this view as applied to White’s Coin Game.

Though Elga does offer an explicit formulation of the principle in his (2004), I am using a different version to fit more clearly with the previous formulation.

See Joyce (2005, Sect. 6) for more information and a fuller version of this argument.

Note that the argument I’ve given doesn’t show that there must be cube-factory-like problems for the particular frequency-based principle that this objector would appeal to. It’s compatible with my claims that the suitably restricted frequency-based principle may only entail a new super highly restricted version of poi that is not subject to cube-factory-like problems. I believe that such a principle would be subject to problems analogous to actual cube factories, but the frequency-based principles would need to be formulated explicitly before we could consider them. Attempts to formulate schematics of those cases have been omitted here due to the complexities of forming clear intuitions about repeated cases each of which involve infinitely-many possibilities.

Another way one might attempt to deflate the Imprecise Bayesian solution is by appeal to a direct inference from objective probabilities, along the lines of Seminar (2008). A worry for this move, as Pust (2011) points out, is that direct inference seems to support the opposite precise conclusion equally well. I suspect that the Imprecise Bayesian would reject this move for a different reason though: in formulating the direct inference defence of thirding, the Oscar Seminar must assume “a uniform probability distribution over times” in hours (2008, p. 152). As I discussed above, it’s central to the Imprecise Bayesian picture that agents must not assume that events are governed by any particular probability distribution without evidence. Doing so has the agent acting as though she has more information than she actually does. For that reason, the Imprecise Bayesian ought to reject the Oscar Seminar’s direct-inference-based solution. It’s possible that an acceptable direct-inference-based solution can be formulated without assuming a distribution over times, but doing so is beyond the scope of this investigation.

References

Bovens, L. (2010). Judy Benjamin is a Sleeping Beauty. Analysis, 70(1), 23–26.

Bovens, L., & Ferreira, J. L. (2010). Monty Hall drives a wedge between Judy Benjamin and the Sleeping Beauty: A reply to Bovens. Analysis, 70(3), 473–481.

Easwaran, K. (2014). Regularity and hyperreal credences. Philosophical Review, 123(1), 1–41.

Elga, A. (2000). Self-locating belief and the Sleeping Beauty problem. Analysis, 60(2), 143–147.

Elga, A. (2004). Defeating Dr. Evil with self-locating belief. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 69(2), 383–396.

Hájek, A. (2003). What conditional probability could not be. Synthese, 137(3), 273–323.

Jeffrey, R. (1983). The logic of decision. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Joyce, J. M. (2005). How probabilities reflect evidence. Philosophical Perspectives, 19(1), 153–178.

Joyce, J. M. (2010a). A defense of imprecise credences in inference and decision making. Philosophical Perspectives, 24(1), 281–323.

Joyce, J. M. (2010b). Do imprecise credences make sense? Retrieved, from http://fitelson.org/joyce_hplms_2x2. Accessed 19 March 2014.

Kaplan, M. (1996). Decision theory as philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levi, I. (1980). The enterprise of knowledge. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lewis, D. (1980). A subjectivist’s guide to objective chance. In R. C. Jeffery (Ed.), Studies in inductive logic and probability (Vol. 2, pp. 83–132). Berkeley: University of California Press. (Reprinted in Philosophical Papers, Vol. II, pp. 83–113).

Lewis, D. (2001). Sleeping Beauty: Reply to Elga. Analysis, 61(3), 171–176.

Monton, B. (2002). Sleeping Beauty and the forgetful Bayesian. Analysis, 62(1), 47–8211.

Pust, J. (2011).Sleeping beauty and direct inference. Analysis, 71(2), 290–293.

Seminar, O. (2008). An objectivist argument for thirdism. Analysis, 68(2), 149–155.

Sturgeon, S. (2008). Reason and the grain of belief. Noûs, 42(1), 139–165.

Titelbaum, M. G. (2013). Ten reasons to care about the Sleeping Beauty problem. Philosophy Compass, 8(11), 1003–1017.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1989). Laws and symmetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1990). Figures in a probability landscape. In J. Dunn & A. Gupta (Eds.), Truth or consequences (pp. 345–356). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1995). Belief and the problem of ulysses and the Sirens. Philosophical Studies, 77(1), 7–37.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (2006). Vague expectation value loss. Philosophical Studies, 127(3), 483–491.

White, R. (2009). Evidential symmetry and mushy credence. In T. Szabo Gendler & J. Hawthorne (Eds.), Oxford studies in epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgments

The kernel of the idea developed here was discovered during conversations with J. Dmitri Gallow and Jason Konek. I am also very grateful to many people who helped to develop my thoughts on this topic including Marie Barnett, Daniel Greco, Alan Hájek, Tristram McPherson, Sarah Moss, Daniel Nolan, Joel Pust, Alex Silk, W. Robert Thomas, members of the University of Michigan Formal Epistemology Working Group, and particularly James M. Joyce.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singer, D.J. Sleeping beauty should be imprecise. Synthese 191, 3159–3172 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-014-0429-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-014-0429-y